Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate changes in influenza vaccination rates in healthy and at-risk children following the implementation of the UK's childhood influenza immunisation programme.

Design

Observational cohort study before and after initiation of the UK's childhood influenza immunisation programme over three influenza seasons (2012–2013, 2013–2014 and 2014–2015) using data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD).

Setting

More than 500 primary care practices in the UK.

Population

All individuals aged 2–17 years on 1 September, with at least 12 months of medical history documented in CPRD were retained in the analysis.

Intervention

Starting in 2013–2014, all children aged 2 and 3 years were offered influenza vaccination through general practice, and primary school-aged children were offered influenza vaccination in selected counties in England (described as pilot regions). The vaccination programme was extended to all children aged 4 years in England in 2014–2015.

Main outcome measure

Cumulative vaccination rate from 1 September to 28 February of the next calendar year as assessed by a time-to-event statistical model (vaccination uptake). Age group, sex, region and type of high-risk medical condition were assessed as predictors.

Results

Vaccination uptake increased considerably from 2012–2013 to 2013–2014 in targeted children aged 2–3 years, both in children with a high-risk medical condition (from 40.7% to 61.1%) and those without (from 1.0% to 43.0%). Vaccination rates increased also, though less markedly, in older children. In 2014–2015, vaccination rates remained higher than 40% in healthy children aged 2–3 years, although they decreased slightly from 2013–2014 (from 43.0% to 41.8%). Vaccination rates in older healthy children continued to increase, driven primarily by an increase in children aged 4 years to 31.3% in 2014–2015.

Conclusions

The introduction of a universal childhood vaccination policy in the UK increased vaccination rates for targeted children, including those with high-risk conditions.

Keywords: Influenza, Vaccination, Uptake, High-risk, Paediatric

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) database of longitudinal general practice medical records allows repeated measurements of influenza vaccination uptake across seasons in a large and representative population in a primary care setting.

The database also allows the identification of patients with high-risk conditions.

It is possible that influenza vaccinations administered outside of general practices—for instance, as part of school-based programmes—are not completely captured in CPRD, resulting in an underestimation of the vaccination rate.

This is the first analysis of its type, investigating vaccination rates in UK children and adolescents with and without high-risk conditions after the implementation of a national vaccination programme.

The findings of this study can aid influenza vaccination policy decision-making in the UK and other countries considering the implementation of childhood influenza vaccination programmes.

Introduction

Influenza immunisation programmes have traditionally targeted those with medical conditions that predispose them to a high risk of influenza complications. In the UK, immunisation programmes provided by the National Health Service have also targeted the elderly; in 2000, the programme was extended to include everyone aged over 65 years. This programme has been successful in reducing influenza-related morbidity and mortality.1 In 2013, the UK initiated the roll-out of a universal childhood vaccination programme for healthy and at-risk children, with live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), based on the recommendation of the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation.2 In the first season of the programme in 2013–2014, children aged 2 and 3 years were offered influenza vaccination, to be administered by their primary care practice. This programme was extended to all children aged 4 years in the 2014–2015 season. In addition, a number of pilot schemes were undertaken in primary and secondary schools across the UK, in particular in Scotland and Northern England, to evaluate the programme in older age groups.3 4

With any new national immunisation programme, it is important to quantify the uptake of the vaccine for the overall target population,5 6 and to evaluate whether coverage necessary for indirect protective effects has been achieved following widespread introduction.

Here, we report the results of an observational cohort study that estimates changes in influenza vaccination rates in UK children with and without high-risk medical conditions, after the implementation of the national immunisation programme, using data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD).

Methods

This observational cohort study was conducted during three influenza seasons, before the implementation of the extended childhood programme (2012–2013) and in its first (2013–2014) and second year (2014–2015). All individuals aged 2–17 years on 1 September 2012 (season 2012–2013), 1 September 2013 (season 2013–2014) and 1 September 2014 (season 2014–2015) with at least 12 months of medical history documented in CPRD were retained in the analysis. These individuals were then followed up for 6 months to estimate the influenza vaccination rate for the season.

CPRD maintains a database of anonymised longitudinal medical records from primary care from over 500 practices in the UK. CPRD is considered to be broadly representative of the UK population.7 Demographic, clinical, referral, therapy and immunisation records were used in this analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC) (Protocol 14_062A). Data were extracted from the databases released by CPRD in July 2015.

Vaccine recipients as well as the vaccination date were identified from immunisation, clinical and therapy records. High-risk groups recommended for vaccination were defined using the operational specifications published by PRIMIS at the University of Nottingham.8 All diagnosis codes since enrolment in CPRD were queried.

The cumulative vaccination rate was analysed from 1 September to 28 February of the next calendar year for each season using Cox proportional hazard models. These are semiparametric time-to-event models that do not make any assumptions about vaccination uptake over the course of an influenza season but assume that the effects of the predictor variables on vaccination uptake are constant over time and independent. Individuals were censored when the general practitioner/practice stopped contributing to CPRD, when the child left the practice, or when the child died, whichever happened first.

Time to vaccination was fitted by a multivariable proportional hazards (Cox's) model that included season, sex, region and type of high-risk condition as potential predictors or confounders. Interaction terms between season and the three other covariates were also introduced in the model to assess any effect modification by season. The models were fitted separately for each age group (2–3, 4–8 and 9–17 years) as the specifications of the national vaccination programme were a function of age and evolved over the three seasons.

All analyses were conducted with SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA).

Participant involvement

This was a non-interventional study using existing data from CPRD. No proactive data collection from the participants was required.

Results

A total of 850 423, 792 257 and 712 143 children and adolescents aged 2–17 years were documented in CPRD on 1 September each year (2012–2014). In total, 794 138, 735 136 and 660 216 children and adolescents were retained in the analysis for the 2012–2013, 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 seasons, respectively, after exclusion of participants with <12 months of medical history (56 285, 57 121 and 51 927, respectively).

The population demographics are presented in table 1. Between 6% and 7% of all children presented with at least one high-risk condition in the 2012–2013, 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 seasons (53 475 children in 2012–2013, 48 254 in 2013–2014 and 41 940 in 2014–2015 season). The most frequent high-risk condition was chronic respiratory diseases, including asthma.

Table 1.

Description of the study population

| Season 2012–2013 n=794 138 |

Season 2013–2014 n=735 136 |

Season 2014–2015 n=660 216 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 2–3 | 13% (99 855) | 13% (93 161) | 13% (83 241) |

| 4–8 | 31% (248 486) | 31% (232 735) | 32% (211 204) |

| 9–17 | 56% (445 797) | 56% (409 240) | 55% (365 771) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 51% (406 251) | 51% (375 999) | 51% (337 454) |

| Female | 49% (387 887) | 49% (359 137) | 49% (322 762) |

| Region | |||

| England/North | 14% (114 636) | 14% (102 314) | 12% (76 849) |

| England/Midlands | 18% (147 158) | 16% (121 547) | 15% (100 850) |

| England/South | 32% (253 833) | 32% (232 379) | 32% (215 025) |

| England/London | 12% (94 681) | 13% (97 368) | 13% (83 585) |

| Northern Ireland | 4% (28 189) | 4% (28 090) | 4% (28 204) |

| Scotland | 11% (85 423) | 12% (85 931) | 13% (84 993) |

| Wales | 9% (70 218) | 9% (67 507) | 11% (70 710) |

| High-risk condition | |||

| Chronic respiratory disease (including asthma) | 5% (40 052) | 5% (35 561) | 5% (30 484) |

| Chronic heart disease | 1% (6892) | 1% (6511) | 1% (5943) |

| Chronic kidney disease | <1% (412) | <1% (385) | <1% (356) |

| Chronic liver disease | <1% (232) | <1% (213) | <1% (183) |

| Chronic neurological disease | <1% (3612) | <1% (3384) | <1% (3031) |

| Diabetes | <1% (2052) | <1% (1969) | <1% (1740) |

| Immunosuppression | <1% (1483) | <1% (1427) | <1% (1301) |

| Other high-risk condition | <1% (391) | <1% (298) | <1% (236) |

| Any of the conditions above | 7% (53 475) | 7% (48 254) | 6% (41 940) |

The vaccination uptake in children aged 2–3 years increased from 40.7% in 2012–2013 to 61.1% in 2013–2014 for those with a high-risk condition and from 1.0% to 43.0% for those without a high-risk condition (table 2). It then decreased slightly in 2014–2015 to 57.0% among children aged 2–3 years with high-risk conditions and to 41.8% in children without high-risk conditions.

Table 2.

Cumulative vaccination rate by age category (point estimate in % and 95% CI)

| Children at risk |

Other children |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | |

| Total population aged 2–17 years | 41.0 (40.5 to 41.5) | 44.4 (43.9 to 44.8) | 43.5 (43.0 to 44.0) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.2) | 8.8 (8.7 to 8.8) | 12.0 (12.0 to 12.1) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 2–3 | 40.7 (38.9 to 42.5) | 61.1 (59.2 to 63.1) | 57.0 (55.0 to 59.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | 43.0 (42.7 to 43.3) | 41.8 (41.4 to 42.1) |

| 4–8 | 41.3 (40.5 to 42.1) | 45.1 (44.3 to 46.0) | 44.2 (43.2 to 45.1) | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.1) | 4.3 (4.2 to 4.4) | 12.7* (12.6 to 12.9) |

| 9–17 | 40.8 (40.3 to 41.3) | 42.6 (42.1 to 43.2) | 42.2 (41.6 to 42.8) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.3) | 3.3 (3.2 to 3.3) | 4.6 (4.5 to 4.6) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 40.6 (40.1 to 41.2) | 44.0 (43.4 to 44.6) | 43.2 (42.5 to 43.8) | 1.2 (1.2 to 1.2) | 8.8 (8.7 to 8.9) | 12.1 (12.0 to 12.2) |

| Female | 41.3 (40.7 to 42.0) | 44.8 (44.1 to 45.5) | 44.0 (43.2 to 44.7) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.2) | 8.7 (8.6 to 8.8) | 12.0 (11.9 to 12.1) |

| Region | ||||||

| England/North | 42.1 (41.0 to 43.2) | 47.3 (46.1 to 48.5) | 45.4 (44.0 to 46.9) | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.2) | 11.4 (11.2 to 11.6) | 11.8 (11.6 to 12.1) |

| England/Midlands | 42.4 (41.4 to 43.4) | 45.2 (44.4 to 45.9) | 46.6 (45.4 to 47.9) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | 6.5 (6.3 to 6.6) | 11.8 (11.6 to 12.0) |

| England/South | 39.9 (39.2 to 40.7) | 42.6 (41.8 to 43.4) | 43.6 (42.8 to 44.4) | 1.3 (1.3 to 1.4) | 7.0 (6.8 to 7.1) | 9.1 (9.0 to 9.3) |

| England/London | 35.4 (34.1 to 36.7) | 37.5 (36.3 to 38.8) | 36.1 (34.7 to 37.6) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 8.2 (8.0 to 8.4) | 7.7 (7.5 to 7.9) |

| Northern Ireland | 56.9 (56.7 to 57.0) | 56.1 (55.8 to 56.3) | 41.2 (41.0 to 41.4) | 1.9 (1.7 to 2.1) | 12.3 (11.9 to 12.7) | 10.4 (10.0 to 10.8) |

| Scotland | 44.8 (43.6 to 46.1) | 51.0 (49.7 to 52.3) | 48.6 (47.3 to 50.0) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 13.3 (13.1 to 13.6) | 25.8 (25.5 to 26.1) |

| Wales | 34.0 (32.7 to 35.2) | 38.5 (37.1 to 39.8) | 39.1 (37.8 to 40.5) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 8.8 (8.5 to 9.0) | 10.2 (10.0 to 10.4) |

| High-risk condition | ||||||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 42.5 (42.0 to 43.0) | 46.0 (45.4 to 46.5) | 45.2 (44.6 to 45.7) | |||

| Chronic heart disease | 30.8 (29.7 to 31.9) | 36.0 (34.8 to 37.2) | 36.0 (34.8 to 37.3) | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 38.7 (33.9 to 43.5) | 37.8 (32.9 to 42.7) | 33.2 (28.2 to 38.2) | |||

| Chronic liver disease | 44.7 (44.1 to 45.4) | 48.0 (47.3 to 48.6) | 45.1 (44.4 to 45.9) | |||

| Chronic neurological disease | 32.6 (31.1 to 34.2) | 36.1 (34.5 to 37.8) | 34.9 (33.2 to 36.7) | |||

| Diabetes | 66.0 (63.9 to 68.1) | 65.9 (63.7 to 68.0) | 64.1 (61.8 to 66.4) | |||

| Immunosuppression | 46.9 (44.3 to 49.4) | 48.1 (45.4 to 50.7) | 45.4 (42.6 to 48.2) | |||

*Vaccination rates of 31.3% (30.8% to 31.8%), 8.3% (8.0% to 8.6%), 8.1% (7.8% to 8.4%), 8.0% (7.7% to 8.2%) and 7.6% (7.4% to 7.9%) in children aged 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 years, respectively.

In 2013–2014, vaccination rates also increased among older children and adolescents with high-risk conditions, from 41.3% to 45.1% in children aged 4–8 years and from 40.8% to 42.6% in children aged 9–17 years. A similar increase was seen in older children and adolescents without high-risk conditions, from 1.1% to 4.3% in children aged 4–8 years and from 1.3% to 3.3% in children aged 9–17 years.

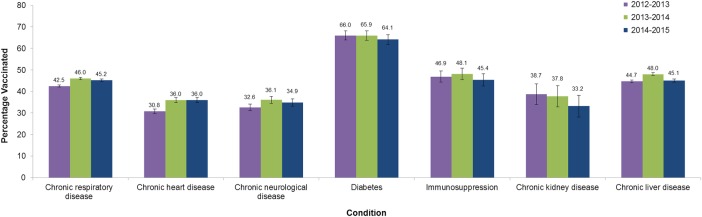

In 2014–2015, vaccination rates in older children and adolescents without high-risk conditions continued to increase from 4.3% in 2013–2014 to 12.7% in 2014–2015, in children aged 4–8 years—primarily driven by an increase in vaccination rates to 31.3% in children aged 4 years—and from 3.3% to 4.6% in children aged 9–17 years. Vaccination rates in children with high-risk conditions remained stable at over 40% and above 2012–2013 rates: 45.1% and 44.2% in children aged 4–8 years, 42.6% and 42.2% in children aged 9–17 years in 2013–2014 and 2014–2015, respectively. The small observed decreases from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015 were statistically non-significant. Vaccination rate by high-risk medical condition is also shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Vaccination rate in children with high-risk medical conditions aged 2–17 years in the 2012–2013, 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 seasons.

Observed vaccination rates in boys and girls were very similar before adjustment for other covariates, but there were important differences between regions, with the highest vaccination rates in Scotland or Northern Ireland and the lowest ones in London.

Adjusted analyses (tables 3 and 4) confirm increases in vaccination rates from season 2012–2013 to seasons 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 in all age groups and in children with or without high-risk medical conditions. Compared with England/South, which was chosen as the reference region because of its larger study population, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of influenza vaccination were higher among children aged 2 and 3 years in Scotland and Northern Ireland. The higher HRs also observed in children 4 years and older in Scotland and England/North probably point to the impact of local school vaccination programmes. Girls aged 9–17 years, with or without high-risk conditions, were more frequently vaccinated than boys in the same age group, while a difference in the opposite direction—higher vaccination rate in boys—was observed in healthy children aged 4–8 years. Among children with high-risk medical conditions, those with diabetes were more likely to be vaccinated than children with chronic respiratory disease, while children with chronic heart disease or chronic neurological diseases were less likely to be vaccinated, irrespective of the age group. HRs of the predictors of vaccination rate, age group and season for children without and with high-risk medical conditions can be found in online supplementary tables A and B, respectively.

Table 3.

HRs of the predictors of influenza vaccination rate among children and adolescents without high-risk condition; presentation by age group

| 2–3 year olds |

4–8 year olds |

9–17 year olds |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate 95% CI | p Value | Estimate 95% CI | p Value | Estimate 95% CI | p Value | |

| Season | ||||||

| 2012–2013 | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| 2013–2014 | 59.91 (56.13 to 64.04) | 4.01 (3.84 to 4.20) | 2.55 (2.47 to 2.64) | |||

| 2014–2015 | 53.97 (50.56 to 57.69) | <0.001 | 12.62 (12.11 to 13.16) | <0.001 | 3.50 (3.39 to 3.61) | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.01† | <0.001† | 0.10† | |||

| Male | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| Female | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0.44 | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.97) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.08) | <0.001 |

| Region | <0.001† | <0.001† | <0.001† | |||

| England/North | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.95) | 2.75 (2.66 to 2.84) | 1.92 (1.84 to 2.00) | |||

| England/Midlands | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.94) | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.18) | 1.68 (1.61 to 1.75) | |||

| England/South | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| England/London | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.70) | 1.50 (1.44 to 1.56) | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | |||

| Northern Ireland | 1.93 (1.87 to 2.00) | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.96) | 2.26 (2.14 to 2.39) | |||

| Scotland | 1.21 (1.19 to 1.24) | 5.18 (5.03 to 5.34) | 4.53 (4.38 to 4.69) | |||

| Wales | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.84) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.96) | <0.001 | 2.74 (2.64 to 2.85) | <0.001 |

*Reference group.

†p Value of the interaction term between season and each other predictor.

Table 4.

HRs of the predictors of influenza vaccination rate among children and adolescents with high-risk medical conditions; presentation by age group

| 2–3 year olds |

4–8 year olds |

9–17 year olds |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate 95% CI | p Value | Estimate 95% CI | p Value | Estimate 95% CI | p Value | |

| Season | ||||||

| 2012–2013 | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| 2013–2014 | 1.83 (1.69 to 1.97) | 1.14 (1.10 to 1.19) | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.09) | |||

| 2014–2015 | 1.52 (1.40 to 1.65) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.12) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.97† | 0.84† | 0.99† | |||

| Male | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| Female | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | 0.48 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | 0.52 | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07) | <0.001 |

| Region | 0.04† | <0.001† | <0.001† | |||

| England/North | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.13) | 1.21 (1.15 to 1.27) | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.11) | |||

| England/Midlands | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.16) | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.27) | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.11) | |||

| England/South | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| England/London | 0.83 (0.74 to 0.93) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.88) | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.85) | |||

| Northern Ireland | 1.64 (1.41 to 1.90) | 1.20 (1.12 to 1.29) | 1.46 (1.40 to 1.53) | |||

| Scotland | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.26) | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) | 1.14 (1.11 to 1.18) | |||

| Wales | 0.89 (0.79 to 0.99) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.91) | <0.001 |

| High-risk condition | 0.27† | <0.01† | 0.04† | |||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 1.00* | 1.00* | 1.00* | |||

| Chronic heart disease | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.92) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.71) | 0.57 (0.54 to 0.59) | |||

| Chronic neurological disease | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.85) | 0.69 (0.65 to 0.74) | 0.61 (0.58 to 0.64) | |||

| Diabetes | 1.55 (1.17 to 2.00) | 1.78 (1.62 to 1.94) | 1.81 (1.74 to 1.88) | |||

| Other high-risk condition‡ | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.40) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.24) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) | <0.001 |

*Reference group.

†p Value of the interaction term between season and each other predictor.

‡Chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, immunosuppression or pregnancy.

bmjopen-2015-010625supp_tables.pdf (156.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

The roll-out of the UK's childhood influenza immunisation programme in 2013–2014, which targeted all children aged 2–3 years and included pilot schemes in older children and adolescents, increased the vaccination rate in children aged 2–3 years without high-risk conditions from 1% to over 40% (HR of 59.9). Vaccination rates also increased in children aged 2 and 3 years with high-risk conditions and in older children as well, with or without high-risk conditions, though the increase was less marked than in children aged 2–3 years. Vaccination rates in 2014–2015 remained higher than 40% in healthy children aged 2–3 years and were increased in older children compared with the 2012–2013 season. The extension of the programme to children aged 4 years in 2014–2015 likely contributed to the increased uptake in children aged 4–8 years relative to the 2012–2013 season. Vaccination rates observed in 2014–2015 in older children with a high-risk medical condition remained stable and significantly higher than in 2012–2013.

Our analysis demonstrated that a universal immunisation policy for influenza can increase vaccination rates in the overall target population and in key subgroups, such as those with high-risk conditions in whom vaccination was already recommended.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The CPRD database of longitudinal general practice medical records allows repeated measurements of vaccination uptake across seasons in a large and representative population in a primary care setting. The database also allows the identification of patients with high-risk conditions.

It is possible that vaccinations administered outside of general practices—for instance, as part of school-based programmes—are not completely captured in CPRD, resulting in an underestimation of the influenza vaccination rate. However, given the observation of higher vaccination rates in regions that implemented widespread school-based vaccination, it is unlikely that this effect is large.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies, discussing important differences in results

The vaccination rates estimated in this study are consistent with public health agency reports in the UK that used different data sources such as ImmForm and the Royal College of General Practitioners database.9 Our study is also in agreement with the 52.5% coverage in England reported by Public Health England for the 2013–2014 season,4 which is higher than the coverage reported for the USA in the same season (38% of children vaccinated).10 Influenza vaccination rates for children with high-risk medical conditions are not uniformly reported and there are few comparable studies in the literature. However, existing data suggest very low uptake in those with high-risk medical conditions in Europe,11–14 the USA15 and Canada16 in the years before age-based universal vaccination recommendations. A number of factors are known to contribute to low influenza vaccination uptake, including individuals' awareness of the seriousness of influenza,13 17 willingness to accept medical advice,17 recommendation from a healthcare worker,13 14 perception of vaccine safety14 and negative media coverage.14 These factors are also likely to extend to parents making the decision as to whether their child should receive the influenza vaccine. The analyses carried out here are useful as they provide a reference range for vaccination rates in children with a universal policy in a European country, as well as insight into some factors that may have affected vaccination uptake in the children with high-risk medical conditions before the universal vaccination policy. The increased uptake in children with chronic respiratory diseases is particularly promising, as rates have failed to increase in previous years in other targeted programmes,17 demonstrating the value of a universal programme on vaccination rates across different segments of the population. However, the European Council target vaccination rate of 75% among children with chronic conditions18 has not yet been met in the UK, despite the UK coming close to elderly vaccination targets of 75%.14 Studies show that other countries in Europe also struggle to meet the recommended vaccination rates,11–13 19 with a comprehensive survey of vaccination rates in the European Union, Norway and Iceland between 2008 and 2011 estimating a vaccination rate of 32.9–71.7%.14

The effectiveness of the UK's universal childhood immunisation programme on influenza-related morbidity was not estimated as part of the analysis reported here, but vaccinating primary school-aged children in pilot areas during the 2014–2015 season resulted in significant and non-significant reductions in a range of surveillance indicators for the targeted age groups and wider society (due to indirect protective effects).20

Meaning of the study: possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policymakers

Seasonal influenza infection poses a significant burden to children, in particular to those with high-risk conditions.21–24 As rates of vaccination in the childhood population with chronic medical conditions have been low to date,9 the increased uptake of the vaccine in high-risk children during the 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 seasons is encouraging. While the UK's universal childhood immunisation policy was justified based on the benefits of direct protection to all children and indirect benefits to the general population,1 2 it appears that this new policy also increases vaccination coverage in high-risk groups of the paediatric population. This finding suggests that general awareness of the importance of influenza vaccination may have been raised as a result of the childhood programme, either directly through the programme materials or word of mouth. The increase in vaccination rates in children with chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma is particularly encouraging as asthma is the most prevalent high-risk condition, as well as one with a relatively high risk of complications from influenza.22

Of note, the USA and Canada already recommend universal influenza vaccination to those 6 months and older; however, the Canadian recommendation has provincial funding only in certain provinces.25 26

Unanswered questions and future research

The UK's childhood influenza immunisation programme will be extended further to include older age groups in the coming years.27 Whether the encouraging increases in vaccination rates seen in the target age group during the first two seasons are replicated in older age groups and over several consecutive seasons will be determined as the programme is expanded.

Studies of future influenza seasons will also confirm whether vaccination rates will continue to increase in those who have chronic medical conditions. Further research that aims at disentangling the direct and indirect effectiveness of influenza vaccination resulting from a high vaccination rate in the paediatric population could also help to validate and optimise national vaccination programmes. The implementation of the UK's childhood influenza immunisation programme provides a unique opportunity to address these questions.

Conclusions

The introduction of a universal childhood influenza vaccination policy in the UK increased vaccination rates for all children in the target population (2–3 years in 2013–2014, 2–4 years in 2014–2015) and also improved vaccination rates in those with high-risk conditions. Vaccination rates increased in older children as well, whether they had a high-risk medical condition or not, although the increase was less marked than in children aged 2–3 years. The results from the first two seasons of the UK's childhood influenza vaccination programme demonstrate that a universal influenza vaccination policy can increase uptake for targeted children, including those with high-risk conditions who were previously recommended.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Talya Underwood, Prime Medical Group, London, UK, funded by AstraZeneca. The opinions, conclusions and interpretation of the data are the responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the discussion of the study design and in developing the manuscript. HCa, HCh and AS undertook the analyses.

Funding: This study was supported by AstraZeneca.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare SR and BB are employees of AstraZeneca, HCa is an employee of MedImmune and AS is a contractor for MedImmune (the biologicals arm of AstraZeneca). MH reports grants from NIHR Health Protection Research Unit (HPRU) in Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), during the conduct of the study; unrestricted research grants from Gilead outside the submitted work. HCh reports grants from NIHR HPRU in Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol in partnership with PHE, during the conduct of the study. This work is produced by the authors under the terms of the research training fellowship issued by the NIHR. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, The National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Transparency: The lead author, SR, confirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1.Baguelin M, Flasche S, Camacho A et al. . Assessing optimal target populations for influenza vaccination programmes: an evidence synthesis and modelling study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001527 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Minutes of the meeting held on Friday 13 April 2012. http://media.dh.gov.uk/network/261/files/2012/05/JCVI-minutes-13-April-2012-meeting.pdf (accessed 4 Feb 2015).

- 3.GOV.UK letter. The flu immunisation programme 2013/14. 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/207008/130613_Flu_Letter_v_29_Gateway_GW_signed.pdf (accessed 4 Feb 2015).

- 4.Pebody RG, Green HK, Andrews N et al. . Uptake and impact of a new live attenuated influenza vaccine programme in England: early results of a pilot in primary school-age children, 2013/14 influenza season. Euro Surveill 2014;19:20823 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.22.20823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas DR, King J, Evans MR et al. . Uptake of measles containing vaccines in the measles, mumps, and rubella second dose catch-up programme in Wales. Commun Dis Public Health 1998;1:44–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce A, Law C, Elliman D et al. , Millennium Cohort Study Child Health Group. Factors associated with uptake of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR) and use of single antigen vaccines in a contemporary UK cohort: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008;336:754–7. 10.1136/bmj.39489.590671.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K et al. . Data Resource Profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:827–36. 10.1093/ije/dyv098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PRIMIS Nottingham. http://www.primis.nottingham.ac.uk/SeasonalFluVaccineUptake/Seasonal_Flu_LQD_Specification_V5.0.8_20131118_FINAL_LIB_101.pdf (accessed 4 Feb 2015).

- 9.Public Health England. Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses, including novel respiratory viruses, in the United Kingdom: Winter 2012/13. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325217/Annual_flu_report_winter_2012_to_2013.pdf (accessed 4 Feb 2015).

- 10.Rodgers L, Pabst LJ, Chaves SS. Increasing uptake of live attenuated influenza vaccine among children in the United States, 2008–2014. Vaccine 2015;33:22–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph C, Goddard N, Gelb D. Influenza vaccine uptake and distribution in England and Wales using data from the General Practice Research Database, 1989/90–2003/04. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:371–7. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coupland C, Harcourt S, Vinogradova Y et al. . Inequalities in uptake of influenza vaccine by deprivation and risk group: time trends analysis. Vaccine 2007;25:7363–71. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loerbroks A, Stock C, Bosch JA. Influenza vaccination coverage among high-risk groups in 11 European countries. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:562–8. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mereckiene J, Cotter S, Nicoll A et al. , VENICE project gatekeepers group. Seasonal influenza immunisation in Europe. Overview of recommendations and vaccination coverage for three seasons: pre-pandemic (2008/09), pandemic (2009/10) and post-pandemic (2010/11). Euro Surveill 2014;19:20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho BH, Kolasa MS, Messonnier ML. Influenza vaccination coverage rate among high-risk children during the 2002–2003 influenza season. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:582–7. 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwong JC, Rosella LC, Johansen H. Trends in influenza vaccination in Canada, 1996/1997 to 2005. Health Rep 2007;18:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keenan H, Campbell J, Evans PH. Influenza vaccination in patients with asthma: why is the uptake so low? Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:359–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Commission of the European Communities. Proposal for a Council recommendation on seasonal influenza vaccination. Brussels; Commission of the European Communities, 2009. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_threats/com/Influenza/docs/seasonflu_rec2009_en.pdf (accessed 4 Feb 2015).

- 19.Blank PR, Schwenkglenks M, Szucs TD. Vaccination coverage rates in eleven European countries during two consecutive influenza seasons. J Infect 2009;58:446–58. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pebody R, Warburton F, Andrews N et al. . Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza in primary care in the United Kingdom: 2014/15 end of season results. Euro Surveill 2015;20(36):pii=30013 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.36.30013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neuzil KM, Wright PF, Mitchel EF Jr et al. . The burden of influenza illness in children with asthma and other chronic medical conditions. J Pediatr 2000;137:856–64. 10.1067/mpd.2000.110445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller EK, Griffin MR, Edwards KM et al. , New Vaccine Surveillance Network. Influenza burden for children with asthma. Pediatrics 2008;121:1–8. 10.1542/peds.2007-1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paget WJ, Balderston C, Casas I et al. . EPIA collaborators. Assessing the burden of paediatric influenza in Europe: the European Paediatric Influenza Analysis (EPIA) project. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:997–1008. 10.1007/s00431-010-1164-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonova EN, Rycroft CE, Ambrose CS et al. . Burden of paediatric influenza in Western Europe: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012;12:968 10.1186/1471-2458-12-968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Olsen SJ et al. . Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, United States, 2015–16 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:818–25. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6430a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2014–2015. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/naci-ccni/flu-grippe-eng.php (accessed 4 Feb 2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.GOV.UK letter. Childhood flu immunisation programme: update and provisional roll-out schedule. 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/331045/2014-15_update_and_roll-out_schedule_letter.pdf (accessed 4 Feb 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010625supp_tables.pdf (156.9KB, pdf)