Abstract

Introduction

Early start of an oral diet is safe and beneficial in most types of gastrointestinal surgery and is a crucial part of fast track or enhanced recovery protocols. However, the feasibility and safety of oral intake directly following oesophagectomy remain unclear. The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of early versus delayed start of oral intake on postoperative recovery following oesophagectomy.

Methods and analysis

This is an open-label multicentre randomised controlled trial. Patients undergoing elective minimally invasive or hybrid oesophagectomy for cancer are eligible. Further inclusion criteria are intrathoracic anastomosis, written informed consent and age 18 years or older. Inability for oral intake, inability to place a feeding jejunostomy, inability to provide written consent, swallowing disorder, achalasia, Karnofsky Performance Status <80 and malnutrition are exclusion criteria. Patients will be randomised using online randomisation software. The intervention group (direct oral feeding) will receive a liquid oral diet for 2 weeks with gradually expanding daily maximums. The control group (delayed oral feeding) will receive enteral feeding via a jejunostomy during 5 days and then start the same liquid oral diet. The primary outcome measure is functional recovery. Secondary outcome measures are 30-day surgical complications; nutritional status; need for artificial nutrition; need for additional interventions; health-related quality of life. We aim to recruit 148 patients. Statistical analysis will be performed according to an intention to treat principle. Results are presented as risk ratios with corresponding 95% CIs. A two-tailed p<0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Ethics and dissemination

Our study protocol has received ethical approval from the Medical research Ethics Committees United (MEC-U). This study is conducted according to the principles of Good Clinical Practice. Verbal and written informed consent is required before randomisation. All data will be collected using an online database with adequate security measures.

Trial registration numbers

NCT02378948 and Dutch trial registry: NTR4972; Pre-results.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial.

Large number of participants (n=148).

Patient-reported outcome regarding quality of life and health economics.

The postoperative protocol in this study might not be applicable to other hospitals, given the vast variety of postoperative care protocols.

Only patients undergoing minimally invasive oesophagectomy with intrathoracic anastomosis are included.

Introduction

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programmes are increasingly being applied following oesophagectomy, resulting in a reduced length of stay, perioperative morbidity and hospital charges.1 Early start of an oral diet is a critical part of ERAS protocols and has been shown to be safe and beneficial in most types of gastrointestinal surgery.2–6 However, the feasibility and safety of oral intake directly following oesophagectomy remain unclear.7

Mostly, a nil-by-mouth regimen is applied during the first postoperative week and a nasojejunal tube or jejunostomy tube is placed to bypass the anastomosis.8 9 This is believed to reduce the incidence and severity of postoperative pneumonia and anastomotic leakage, although no causal relationship has been established. On the other hand, a nasojejunal tube or jejunostomy may cause patient discomfort and is associated with complications that may hamper recovery.7 10

The best time to start oral intake following oesophagectomy is unknown. A delay in initiation of oral diet of 4 weeks following oesophagectomy was shown to be beneficial in two retrospective cohort studies.11 12 Both studies found a significant reduction in anastomotic leakage with an extended delay of oral nutrition following oesophagectomy compared with a conventional 5–7 days nil-by-mouth regimen. However, these studies were at risk for bias and extrapolation of these results to the clinical situation may not be valid.11 12

On the other hand, early initiation of oral nutrition has been shown to be feasible in many types of upper gastrointestinal surgery.4 13 Furthermore, a feasibility study suggested that direct oral intake following oesophagectomy is feasible and does not result in an increase in major complications.14 Pulmonary complications were not significantly different in patients who were orally fed directly after surgery, when compared with a historical cohort in which oral intake was delayed. Interestingly, direct oral intake even resulted in less postoperative pulmonary complications. It remains unclear what the best strategy is for postoperative diet protocols in the early postoperative phase following oesophagectomy.

The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of early start versus delayed start of oral intake on postoperative recovery following oesophagectomy.

Methods and analysis

Design

The design of this study is a multicentre prospective open-label randomised controlled trial performed at the Catharina Hospital Eindhoven and the Hospital Group Twente. Both hospitals are situated in the Netherlands. Additional centres will be approached to increase the inclusion rate. The aim of this superiority trial is to investigate the effects of early start versus delayed start of oral intake on postoperative functional recovery following oesophagectomy. It is expected that patients will be included over a period of 2 years. Based on a previous study, it is expected that 80–90% of eligible patients can be included. Perioperative protocols are standardised.

Study population

Patients undergoing elective minimally invasive or hybrid (laparoscopy and thoracotomy) oesophagectomy for cancer with intrathoracic anastomosis are eligible for inclusion. They have to be aged at least 18 years. Exclusion criteria are inability for oral intake (congenital or traumatic anatomical abnormalities), inability to place a feeding jejunostomy, inability to provide written consent, swallowing disorder, achalasia, Karnofsky Performance Status <80 and malnutrition. Malnutrition is defined as >15% weight loss before start of surgery. The investigator and the responsible surgeon verify eligibility. The patient will receive written and verbal information about this trial during a scheduled appointment. Sufficient time to enquire about details of this trial is offered.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

The sample size calculation is based on functional recovery as the primary outcome. Functional recovery is the time to surgical recovery according to the definition described previously.15–17 On the basis of historical controls, patients receiving delayed oral feeding were at least considered to be functionally recovered by a mean of 12 days postoperatively. Patients who were fed orally directly after oesophagectomy were at least functionally recovered at day 10 postoperatively (mean). Using a power of 80%, an α of 5% and an SD of 4 days, a total of 128 patients (64 patients in each group) are needed to show this difference. It is expected that the primary outcome will not be normally divided, and therefore an extra 15% inclusion is necessary, requiring a total of 148 patients (74 patients in each group). An independent physician will perform a safety analysis following 50 and 100 patients. A Haybittle-Peto boundary principle is used regarding anastomotic leakage, (aspiration) pneumonia or mortality.

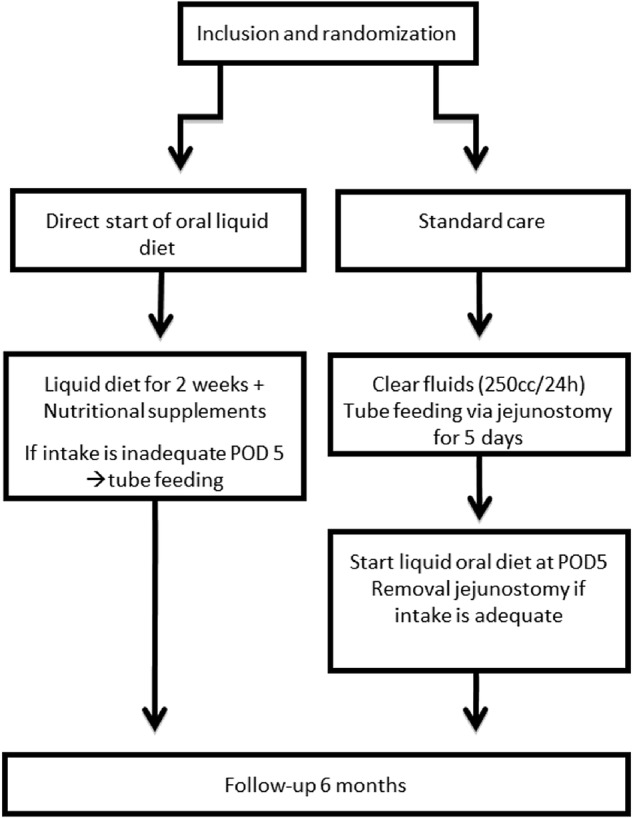

Randomisation

After obtaining written informed consent, patients will be randomly assigned to one of two groups by online randomisation software (TENALEA Clinical Trial Data Management System). This computerised program will generate a randomisation list. A corresponding randomisation website will be used that generates the sequential randomisation number corresponding to the stratified randomisation list on randomisation of a patient. The hospital of inclusion and treatment and type of surgery (hybrid/total minimally invasive) are stratification criteria in the randomisation process. Randomisation will be performed before surgery and after neoadjuvant therapy (∼3 weeks before surgery). The result of the randomisation will be communicated at the outpatient clinic, via a telephone call or at admission (1 day prior to surgery). The flow diagram for participants included in this study is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study protocol flow chart. POD5, postoperative day 5.

Perioperative procedure

Experienced surgeons who carry out more than 30 oesophagectomies yearly perform a hybrid or completely minimally invasive two-stage oesophagectomy with intrathoracic anastomosis (Ivor-Lewis). Patients in both groups receive similar preoperative treatment, including regular consultations by a dietician for assessment of supplemental feeding and by a physiotherapist, especially during periods of neoadjuvant treatment. The type of intrathoracic anastomosis (eg, side-to-side, circular, end-to-end) is left to the preference of the surgeon. A low-vacuum (Jackson Pratt, JP) drain is placed near the anastomosis on the dorsal side of the anastomosis and bilateral chest drains will be placed at the end of the procedure. The nasogastric tube will be removed at the end of the procedure in all patients. A jejunostomy catheter (9.6Fr) is placed during surgery in all patients (both groups) using the Seldinger technique.18 Jejunostomy catheters in the intervention group are sealed and may only be used when an artificial route for enteral feeding is required or when caloric intake is not reached at postoperative day 5 (POD5). Postoperative nursing protocol with elevation of the bed (head rest) is standard care after an oesophagectomy. Amylase levels will be determined postoperatively in the drain fluid of the JP drain and will be correlated with the incidence of anastomotic leakage.

Nutritional procedure

Patients in the early diet group will receive a liquid oral diet (soup, yoghurt, porridge, liquefied solid foods, etc) supported by nutritional supplements (sip feeds) directly postoperatively until postoperative day 14. This liquid oral diet will be expanded gradually and a solid diet will be started at POD15.

Patients in the control group will receive standard tube feeding after surgery via a feeding jejunostomy. These patients are allowed to drink clear liquids up to 250 cc/day. After 5 days, patients in the control group will start with a liquid oral diet from 2 weeks onwards. On postoperative day 20, a solid diet will be started. Tube feeding will be stopped when at least 50% of the daily needs are met with oral nutrition alone.

A dietician will calculate energy needs for each patient using the Harris-Benedict formula with a surplus of 30% for energy expenditure in the postoperative phase. On postoperative days 2, 5 and 14, caloric intake and protein intake are measured and calculated. When patients in the group of early oral intake have not reached an intake >50% of the calculated energy expenditure at postoperative day 5, tube feeding will be started. Tube feeding can be started via the jejunostomy present in all patients. No standard parenteral feeding is initiated to bridge the start of enteral feeding. In case enteral nutrition is not possible or not wanted (eg, due to a chylothorax), parenteral feeding will be started.

Outcomes

The primary outcome parameter is functional recovery (table 1), defined as postoperative patients who are free of intravenous fluid, have adequate pain control, restoration of mobility to an independent level, sufficient caloric intake and no signs of active infection.15–17 Date of functional recovery is the day when all criteria are met.

Table 1.

Functional recovery criteria

| Criteria | Objective measurement | Side notes |

|---|---|---|

| Adequate pain control with oral analgesia | Numeric Rating Scale <5 or Visual Analogue Score <5 | |

| Restoration of mobility to an independent level | Walk to the toilet with/without walking aids and transfer bed/chair | Only possible if preoperative mobility is independent |

| Ability to maintain sufficient caloric intake | Minimum of 50% required calories | |

| Absence of intravenous fluid administration | ||

| No signs of active infection |

|

Functional recovery is reached when all of the criteria are met.

CRP, C reactive protein.

Secondary outcome parameters include pulmonary complications (pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory insufficiency requiring intubation); anastomotic leakage; nutritional status; need for artificial nutrition (total parenteral nutrition/tube feeding); need for additional surgical, radiological or endoscopic interventions; 30-day surgical complications (classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification); other complications requiring treatment; need for intensive care unit (ICU) readmission and total length of ICU stay and health-related quality of life. Long-term outcome parameters such as local recurrence, overall and cancer-specific survival will be registered in a database.

Definitions

Patient characteristics and clinical parameters are registered in an electronic database. Surgical complications are registered for 30 days postsurgery. All surgical complications are classified using the Clavien-Dindo classification.19 Nutritional intake and drain amylase measurements are closely monitored postoperatively until POD14. Nutritional status will be measured using the actual caloric and protein intake versus the needed caloric and protein intake.

Quality of life and symptoms are scored using the ‘European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer’ questionnaire (QLQ-C30/EORTC-OG25).20 These questionnaires are reliable and valid instruments to investigate the quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Patients are asked to complete this questionnaire online or on paper during regular follow-up: at baseline (5 weeks after neoadjuvant treatment) and at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months postoperatively. Long-term outcome parameters such as local recurrence, overall and cancer-specific survival will be prospectively registered in a database.

Pneumonia is defined according to the Uniform Pneumonia Score.21 Aspiration pneumonia is scored separately, defined as pneumonia following clinical aspiration of saliva, liquid or solid food or vomit.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is defined according to the Berlin definition.22

Anastomotic leakage is graded according to Low et al23 and defined as any sign of leakage of the oesophagogastric anastomosis at endoscopy, reoperation, radiographic investigations, postmortem examination or when gastrointestinal contents were found in drain fluid. Type I is defined as leakage treated with intravenous antibiotics and a nil-by-mouth regime. Type II is defined as leakage treated by endoscopic or radiological reinterventions. Type III is defined as leakage treated with a surgical intervention.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will be done according to the intention-to-treat approach in which all randomised patients are included, regardless of adherence to study protocol. Occurrences of the primary and secondary end points are compared between the treatment groups. Results are presented as risk ratios with corresponding 95% CIs. A two-tailed p<0.05 is considered statistically significant. Continuous parameters (functional recovery, nutritional status, length of ICU stay and quality of life) will be checked for normal distribution and an unpaired Student's t-test will be performed when appropriate, otherwise the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical parameters (pulmonary complications, anastomotic leakage, need for artificial nutrition, need for additional surgical, radiological or endoscopic interventions, 30-day surgical complications, other complications requiring treatment, need for ICU readmission) are compared between groups and checked for significant differences with χ2 or Fisher's exact test if cell count is <5.

Monitoring

This prospective randomised clinical trial will be conducted according to the rules of Good Clinical Practice (GCP). In a previous feasibility trial investigating direct oral intake following oesophagectomy, an independent data safety monitoring board was appointed to monitor patient safety. Early start of oral nutrition was shown to be safe and not associated with more complications. Therefore, a data and safety monitoring board was not installed for this study.

Follow-up of adverse events (AEs)

All AEs will be followed until they have abated, or until a stable situation has been reached. Depending on the event, follow-up may require additional tests or medical procedures as indicated and/or referral to the general physician or a medical specialist. Serious AEs (SAEs) need to be reported until end of study.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics approval

The sponsor/investigator will submit a summary of the progress of the trial to the accredited Medical research Ethics Committees United (MEC-U) once a year. Information will be provided on the date of inclusion of the first participant, numbers of participants included and numbers of participants who have completed the trial, SAEs/serious adverse reactions, other problems and amendments.

Amendments

All amendments will be notified to the MEC-U. Non-substantial amendments (eg, typing errors or administrative changes) will not be notified to the MEC-U, but will be recorded and filed by the sponsor.

Consent or assent

All patients who meet the inclusion criteria and do not have exclusion criteria will be asked to participate in the study. After full explanation of the study protocol, informed consent will be obtained. Informed consent will be obtained from each participating patient in oral and written form prior to randomisation. Patients will receive sufficient time to consider participating in this trial. Patients are informed that declining inclusion in this trial will not harm their further treatment. A member of the research group, a physician or nurse practitioner, will obtain informed consent.

Confidentiality

All study-related information will be stored securely at the study sites. All participant information will be stored in locked file cabinets in areas with limited access. Digital files are kept in password-protected applications and folders. Participants' study information will not be released outside of the study without the written permission of the participant.

Access to data

The obtained results will be handled confidentially and will only be accessible and viewed by study personnel, the ethical committee and the Dutch Health Inspection. Data will be coded so that anonymity is preserved and also when data are published. The data will be kept in storage for 15 years.

Ancillary and post-trial care

An insurance policy is made for all patients in the study. They will be insured for injury or death due to participation in this study during the study period and for 4 years after termination of this study.

Dissemination policy

Results of this trial will be published in a peer-reviewed journal. The abstract will be submitted for oral or poster presentations at several surgical conferences.

Authorship is granted to authors who make important contributions to the creation of the final publication. Authors can contribute via written or physical help in this clinical trial.

After completion of this trial, our data set will be made available on request.

Discussion

This trial will investigate two different strategies of postoperative feeding after oesophagectomy, early oral feeding versus delayed oral feeding. Although various approaches are considered to be feasible, the best strategy remains unclear.7

Early enteral feeding after oesophagectomy compared with parenteral feeding restores bowel function9 and reduces the rate of life-threatening complications.8 Common practice is a nil-by-mouth regimen and placement of a jejunostomy catheter during the first postoperative week following oesophagectomy. However, jejunostomy feeding is associated with minor complications including entry site infection, entry site leakage and gastrointestinal tract symptoms with a small risk for reoperation and mortality.7 This could potentially hamper functional recovery resulting in a longer hospital stay.

An important argument to delay oral intake after an oesophagectomy is to reduce sequelae of anastomotic leakage and reduce the risk of (aspiration) pneumonia.11 12 These two studies based their conclusions on a retrospective analysis of historic patient data. To the best of our knowledge, no prospective studies compared early oral feeding with delayed oral feeding after oesophagectomy.

On the other hand, early start of oral intake has been shown to be beneficial in ERAS programmes in many types of gastrointestinal surgery, including upper gastrointestinal surgery. However, data including patients who underwent an oesophagectomy are scarce. A previous safety and feasibility trial performed by our group proves that direct oral intake following oesophagectomy is safe and does not result in an increase in major complications such as pneumonia and anastomotic leakage (TJ Weijs, GHK Berkelmans, GAP Nieuwenhuijzen, et al. Forthcoming 2016).

We hypothesise that early initiation of oral diet following oesophageal surgery can improve functional recovery by a mean of 2 days. Furthermore, possible future benefits include less discomfort of jejunostomy feeding and its potential complications and quality of life may be improved by early start of oral intake.

Footnotes

Contributors: GHKB, TJW, MDPL, EAK and MJvD designed the study. GHKB and MDPL wrote the ethical board proposition. GHKB, BJWW, TJW, MDPL, EAK, MJvD, KK, MN and GAPN contributed to the writing of the study protocol.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This protocol's site-specific informed consent forms, education and recruitment materials are reviewed and approved (1 September 2015) by Medical research Ethics Committees United (MEC-U).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Shewale JB, Correa AM, Baker CM et al. , University of Texas MD Anderson Esophageal Cancer Collaborative Group. Impact of a fast-track esophagectomy protocol on esophageal cancer patient outcomes and hospital charges. Ann Surg 2015;261:1114–23. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hur H, Kim SG, Shim JH et al. . Effect of early oral feeding after gastric cancer surgery: a result of randomized clinical trial. Surgery 2011;149:561–8. 10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klappenbach RF, Yazyi FJ, Alonso Quintas F et al. . Early oral feeding versus traditional postoperative care after abdominal emergency surgery: a randomized controlled trial. World J Surg 2013;37:2293–9. 10.1007/s00268-013-2143-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassen K, Kjaeve J, Fetveit T et al. . Allowing normal food at will after major upper gastrointestinal surgery does not increase morbidity: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg 2008;247:721–9. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815cca68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pragatheeswarane M, Muthukumarassamy R, Kadambari D et al. . Early oral feeding vs. traditional feeding in patients undergoing elective open bowel surgery—a randomized controlled trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:1017–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reissman P, Teoh TA, Cohen SM et al. . Is early oral feeding safe after elective colorectal surgery? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 1995;222:73–7. 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weijs TJ, Berkelmans GH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA et al. . Routes for early enteral nutrition after esophagectomy. A systematic review. Clin Nutr 2015;34:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita T, Daiko H, Nishimura M. Early enteral nutrition reduces the rate of life-threatening complications after thoracic esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer. Eur Surg Res 2012;48:79–84. 10.1159/000336574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao-Bo Y, Qiang L, Xiong Q et al. . Efficacy of early postoperative enteral nutrition in supporting patients after esophagectomy. Minerva Chir 2014;69:37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watters JM, Kirkpatrick SM, Norris SB et al. . Immediate postoperative enteral feeding results in impaired respiratory mechanics and decreased mobility. Ann Surg 1997;226:369–77. doi:discussion 77-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolton JS, Conway WC, Abbas AE. Planned delay of oral intake after esophagectomy reduces the cervical anastomotic leak rate and hospital length of stay. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:304–9. 10.1007/s11605-013-2322-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomaszek SC, Cassivi SD, Allen MS et al. . An alternative postoperative pathway reduces length of hospitalisation following oesophagectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:807–13. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willcutts KF, Chung MC, Erenberg CL et al. . Early oral feeding as compared with traditional timing of oral feeding after upper gastrointestinal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2016;264:54–63. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weijs TJ, Berkelmans GHK, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP et al. . Immediate postoperative oral nutrition following esophagectomy; a multicenter clinical trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2016. [Epub ahead of print 11 Jun 2016]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Dam RM, Hendry PO, Coolsen MME et al. . Initial experience with a multimodal enhanced recovery programme in patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Surg 2008;95:969–75. 10.1002/bjs.6227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dam RM, Wong-Lun-Hing EM, van Breukelen GJP et al. . Open versus laparoscopic left lateral hepatic sectionectomy within an enhanced recovery ERAS programme (ORANGE II-Trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:54 10.1186/1745-6215-13-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlug MS, Bartels SAL, Wind J et al. . Which fast track elements predict early recovery after colon cancer surgery? Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1001–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seldinger SI. Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta Radiol 1953;39:368–76. 10.3109/00016925309136722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B et al. . The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–76. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weijs TJ, Seesing MF, van Rossum PS et al. . Internal and external validation of a multivariable model to define hospital-acquired pneumonia after esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20:680–7. 10.1007/s11605-016-3083-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD et al. . Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 2012;307:2526–33. 10.1001/jama.2012.5669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I et al. . International consensus on standardization of data collection for complications associated with esophagectomy (ECCG). Ann Surg 2015;262:286–94. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]