Abstract

Objectives

Kaizen, or continuous improvement, lies at the core of lean. Kaizen is implemented through practices that enable employees to propose ideas for improvement and solve problems. The aim of this study is to describe the types of issues and improvement suggestions that hospital employees feel empowered to address through kaizen practices in order to understand when and how kaizen is used in healthcare.

Methods

We analysed 186 structured kaizen documents containing improvement suggestions that were produced by 165 employees at a Swedish hospital. Directed content analysis was used to categorise the suggestions into following categories: type of situation (proactive or reactive) triggering an action; type of process addressed (technical/administrative, support and clinical); complexity level (simple or complex); and type of outcomes aimed for (operational or sociotechnical). Compliance to the kaizen template was calculated.

Results

72% of the improvement suggestions were reactions to a perceived problem. Support, technical and administrative, and primary clinical processes were involved in 47%, 38% and 16% of the suggestions, respectively. The majority of the kaizen documents addressed simple situations and focused on operational outcomes. The degree of compliance to the kaizen template was high for several items concerning the identification of problems and the proposed solutions, and low for items related to the test and implementation of solutions.

Conclusions

There is a need to combine kaizen practices with improvement and innovation practices that help staff and managers to address complex issues, such as the improvement of clinical care processes. The limited focus on sociotechnical aspects and the partial compliance to kaizen templates may indicate a limited understanding of the entire kaizen process and of how it relates to the overall organisational goals. This in turn can hamper the sustainability of kaizen practices and results.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, Kaizen, Employee suggestion programme, Quality improvement, lean thinking

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Employees' improvement suggestions captured in kaizen templates that were filled in during 1 year at eight units in a hospital setting were analysed.

A directed content analysis was carried out that was guided by categories and subcategories that were clearly defined.

Data were classified independently by two researchers to foster dependability and credibility in the analysis, and disagreements checked by a third researcher.

A design that includes other sources of data (eg, interviews and observations) would have provided more insights into how kaizen works in practice, such as on the influence of contextual factors.

The focus of this study was constrained to the content of ideas developed through an employee suggestion system; however, the system was part of a wider kaizen approach, and therefore the findings should be prudently transferred to kaizen practices in general.

Introduction

The management practice lean has become one of the most commonly used improvement approaches in healthcare.1 Lean is based on the continuous improvement of processes achieved by either increasing customer value or reducing non-value-adding activities, and by reducing process variation and poor work conditions.2 There is promising evidence that lean helps to improve efficiency and quality in the short term.3 4 However, sustainability of results after the initial period of short-term gains has been proven difficult to achieve,5 6 and there is only limited understanding of factors influencing variation in results across organisational settings.5 7 Plausible explanations for some of the observed limitations can be found in the scope of the lean improvement efforts. The types of outcomes addressed have mainly focused on operational aspects of performance, while little attention has been paid to sociotechnical aspects, such as employees' health, well-being and creativity.8–10 Studies on the types of organisational processes involved have shown that lean has mainly concerned manufacturing-like processes, such as laboratory processes,11 and processes within one unit and not across organisational boundaries.8 It has also been suggested that lean practices may be more successful when applied to services characterised by a low degree of complexity.5 The incremental approach to lean improvement has furthermore been perceived as an inhibitor to an organisations' ability to innovate, as the focus is on improving existing products, services and processes, rather than on finding new ways of doing things.12 Limited compliance to a scientific approach on improvement may also explain the challenges to continuously improve.8 13

Thus, there is a need to deepen our understanding on how lean works in healthcare. Continuous improvement lies at the core of lean, and is referred to as kaizen, a Japanese word that means ‘good change’.14 The kaizen principle is about striving for perfection through the ongoing involvement of employees in practices that enable them to incrementally propose ideas for improvement, solve problems and sustain results over time.15 16 Examples of practices are kaizen blitz, continuous process improvement teams and employee suggestion programmes.17 Kaizen blitz, sometimes referred to as ‘kaizen events’ or rapid improvement events, are generally short-term projects, often conducted in the format of a 3-day to 5-day work session focused on a specific process or set of activities.18 These projects typically involve the analysis of current processes, the development of ideal processes and initial implementation of the changes needed to eliminate non-value-adding steps.19 The scope of the changes is on all or part of a specific process, rather than on broad organisation practices, policies or technology changes, and requires little investment.20 21 Continuous process improvement teams and employee suggestion programmes are compared to kaizen blitz, long-term initiatives where staff meets regularly over time.22 While kaizen lies at the core of lean, most studies focus on evaluating the effects of continual improvement efforts and there is only limited understanding of how the kaizen principle is put into practice in healthcare.23

Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe the types of issues and improvement suggestions that hospital employees feel empowered to address through kaizen practices in order to understand when and how kaizen is used in healthcare. We specifically focused on the improvement ideas captured through an employee suggestion system at a hospital adopting multiple kaizen practices to support continual improvement.

Methods

Case characteristics: the hospital and its history of working with kaizen

The study was conducted in a regional hospital in Sweden with ∼500 employees. At the hospital a kaizen programme, which includes the use of an employee suggestion system, for continuous improvement is ongoing since 2009. The initial implementation of kaizen was supported by an external consultant that still provides support and assistance, when needed, to the hospital units working with kaizen. The units provide clinical services as well administrative and support services. The units have the autonomy to organise their kaizen practices as they see fit, but the general work process described below is the same for all units.

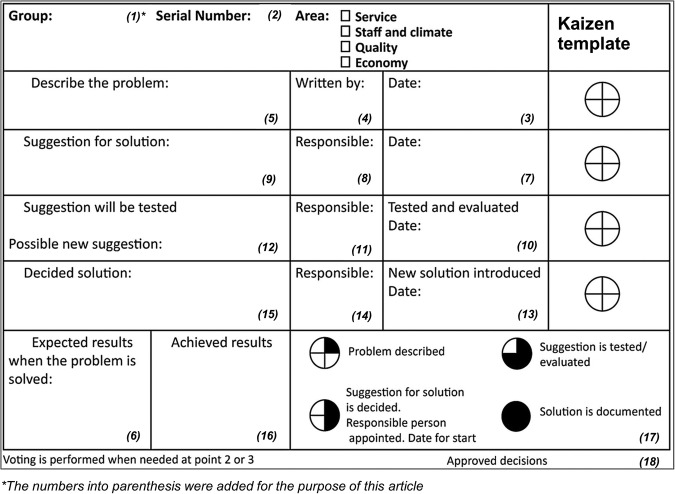

At each unit, employees are encouraged to propose improvement suggestions. The improvement process, that builds on the plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycle,13 is documented in specifically designed kaizen templates (figure 1) that are displayed on a wall, visible for all staff members. The paper template consists of 18 items that address the problem area (service level, quality and safety, work environment, and economics), the description of the problem and the suggestions proposed, the decision on the solution to test and to implement, as well as expected and achieved results. We will use the term kaizen documents for the filled in kaizen templates.

Figure 1.

The kaizen template used to document the improvement process at the hospital. The note has been translated from Swedish to English (amended and published with permission from KAIZEN support).

Individual employees can decide to what extent to fill in the kaizen template individually. The minimum requirement is to fill in information about the identified problem but they can also provide ideas for how to address the problem. The rest of the information in the kaizen template is compiled as the improvement efforts move along.

Regular short meetings are organised with all employees in each unit from one up to four times a month, where initial proposals are discussed and decisions made on whether they should be implemented or further explored. Typically, no ideas are rejected, but not all improvement ideas lead to a change in practice because of economic constraints, the complexity of the issue or disagreement among staff. The duration of the meetings vary depending on the complexity of the issue discussed. When decisions can be made on the stop, the meetings can be very short and last about 5 min. For more complex issues the meetings can be longer and a small team is put together to carry out the improvement cycle, resembling the kaizen event practice, until the next meeting. When needed, improvement ideas are brought up to higher organisational levels.

One to three employees at each unit serve as kaizen representatives and one member of staff serves as a kaizen coordinator for the hospital level. The coordinator brings all representatives from the units together a few times a year and keeps track of which and how many improvement suggestions each hospital units produces. The number of implemented suggestions is linked to a financial reward that can be used for staff activities.

Eight units delivering geriatric care, internal medicine, gynaecology, intensive care, surgery, palliative care, rehabilitation and radiology were included in the current study. Eight other units were excluded as they were a part of an intervention study in which the employee health promotion activities were integrated with the kaizen work.24 These units were excluded because this health promotion intervention was deemed to influence the original kaizen practices, and thus making it harder to understand when and how kaizen practices were used.

Data collection and analysis

The kaizen documents filled in by the 165 employees working at the included units in 2013 were collected in January 2014, resulting in 186 documents that were used for analysis. This study was conducted about 4 years after the initial implementation of kaizen practices, which enabled us to study them when they were in full operation. All the written text from the kaizen documents (figure 1) was transcribed into an Excel file based on the template's questions, here after called items. The filled parts of the PDSA cycle was an item also noted.

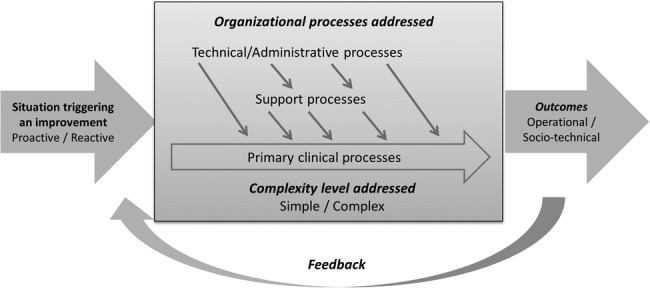

Directed content analysis25 was used to analyse the text written in the kaizen documents. In the analysis we explored four main dimensions. First, the situation that triggered the use of the kaizen document, which could be a reaction to a perceived problem to be solved or a proactive initiative to test new ideas not clearly stemming from a problem. Second, the type or organisational process targeted, which could involve one of three main types of organisational processes, that is, technical and administrative support, and primary clinical processes, or a mixture of them.26 Third, the complexity level involved in the situation addressed that could vary from simple to more complex.27 Fourth, the type of outcomes addressed and expected, which could be operational or sociotechnical.10 Figure 2 provides an overview of the four perspectives included in analysis and how they relate to each other.

Figure 2.

Overview of the four perspectives that guided the analysis and how they relate to each other.

Detailed definitions of the categories and subcategories that guided the directed content analysis as well as the items included are presented in table 1. The development of clear definitions based on the literature strengthened the trustworthiness of the research process. In addition to the four dimensions in table 1, we also assessed the degree of compliance to the kaizen template items.

Table 1.

Definition of the categories and subcategories used in analyses and their relation to the research questions

| Categories | Subcategories | Definition | Items in the kaizen template included in the analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Situation triggering an improvement suggestion | Proactive | Idea for improvement, not clearly stemming from a problem | 5, 6 |

| Reactive | A reaction to a problem encountered that is clearly described | ||

| Organisational processes addressed26 | Primary clinical process | Set of activities to diagnose, treat and care for patients and address specific health problems | 5, 6, 9, 12, 15, 16 |

| Support processes | Set of activities that support the primary clinical process but do not (alone) improve patient health (eg, diagnostic processes, medication management) | ||

| Technical/administrative Processes | Set of activities that deal with the structures and infrastructures needed for the general functioning of the hospital that not directly involve patients or healthcare professionals (eg, payment of staff or the supply of goods or services, physical environment) | ||

| Complexity level in the issues addressed and improvement actions proposed27 | Simple | One or very few components, interventions, outcomes, actors and/or units are involved | 5–6, 9, 12, 15, 16 |

| Complex | Many components, interventions, outcomes, actors and/or units involved | ||

| Outcomes addressed/expected10 | Operational | Reduces non-value-adding activities, leads to increased effectiveness, efficiency and productivity (eg, increased service quality and patient safety, better use of resources) | 9, 12, 15, 16 |

| Sociotechnical | Improves aspects related to staff and work environment (eg, job satisfaction, stress, worker health, safety and well-being, work performance, innovation and creativity, organisational involvement, and organisational citizenship) |

The analysis was performed in several steps by the first and last authors. First, the entire material was read through to get a sense of the whole. Second, categories based on the framework (figure 1) were pilot tested on parts of the data and definitions were agreed on. In a third step, the two researchers independently categorised the entire data. The independent classification by two judges was done to ensure dependability and credibility. Inter-rater reliabilities (Cohen's κ) of 0.92, 0.97, 0.97 and 0.96 were calculated for the four main categories respectively. In the few cases where there was disagreement on the categorisation, a third judge's opinion was sought (the second author) for a majority decision. Frequencies and proportions of classified items in each subcategory were calculated for the total data set and also separately for the eight units.

To assess the degree of compliance to the kaizen template items (ie, to which degree the staff had filled in text for the items in the template, including marked anything in the PDSA cycle's phases), the frequencies and proportions of information in the kaizen template items were calculated for all the kaizen documents.

Results

Overview of the content in the kaizen documents

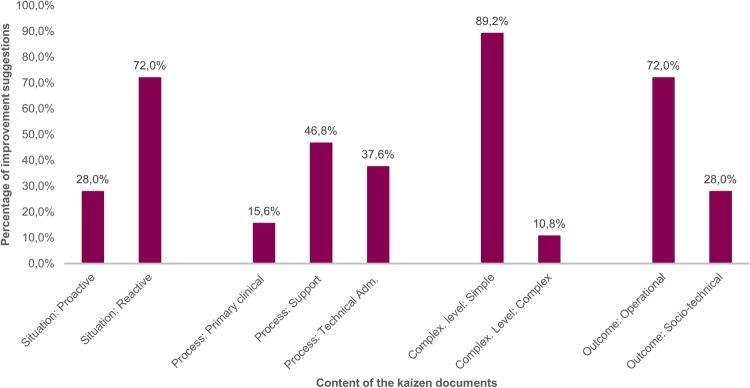

Figure 3 provides an overview of the percentage of the kaizen documents in the four categories and subcategories. In table 2, these results are presented at unit level.

Figure 3.

Percentage of improvement suggestions assigned to subcategories within each category (type of situation; type of process addressed; complexity level; type of outcomes).

Table 2.

Number of staff and kaizen documents, and the percentage of the improvement suggestions in each subcategory per unit

| Unit | Staff 2013 | Kaizen documents | Situation triggering the suggestion |

Type of organisational process |

Complexity |

Type of outcome |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proactive | Reactive | Technical | Support | Primary | Simple | Complex | Operative | Sociotechnical | |||

| n | n | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | n/% | |

| 1 | 35 | 63 | 14/22 | 49/78 | 24/38 | 34/54 | 5/8 | 59/94 | 4/6 | 34/54 | 29/46 |

| 2 | 6 | 17 | 5/29 | 12/71 | 10/59 | 6/35 | 1/6 | 16/94 | 1/6 | 13/76 | 4/24 |

| 3 | 36 | 22 | 7/32 | 15/68 | 7/32 | 8/36 | 7/32 | 20/91 | 2/9 | 15/68 | 7/32 |

| 4 | 10 | 30 | 12/40 | 18/60 | 8/27 | 21/70 | 1/3 | 28/93 | 2/7 | 27/90 | 3/10 |

| 5 | 15 | 19 | 9/47 | 10/53 | 5/26 | 9/47 | 5/26 | 15/79 | 4/21 | 16/84 | 3/16 |

| 6 | 19 | 11 | 2/18 | 9/82 | 6/55 | 3/27 | 2/18 | 9/82 | 2/18 | 10/91 | 1/9 |

| 7 | 21 | 5 | 1/20 | 4/80 | 4/80 | 0/0 | 1/20 | 4/80 | 1/20 | 3/60 | 2/40 |

| 8 | 23 | 19 | 2/11 | 17/89 | 6/32 | 6/32 | 7/37 | 15/79 | 4/21 | 16/84 | 3/16 |

Situations that triggered improvement suggestions

A majority (72%) of the kaizen documents were related to a problem identified and thus categorised as reactive. At unit level the proportion of reactive kaizen documents varied from 53% to 89% (table 2). Examples of reactive activities included an identified problem and need to improve documentation related to the process of discharging patients or substitute broken equipment. An example of a proactive activity was a suggestion to buy oil colour and canvas to enable patients in palliative care to draw paintings for decorating the wards. This example was considered as proactive as it originated from a willingness to create a warm and pleasant environment for patients, rather than stemming from an identified problem.

Type of organisational processes addressed

In 47% of the cases (n=87), the kaizen documents addressed support processes, in 38% (n=70) technical/administrative processes and in 16% (n=29) primary clinical processes (figure 3). In four of the units, the majority of the kaizen documents addressed support processes, while in three units, the majority of the documents addressed technical/administrative processes. Only in one unit, most kaizen documents addressed the primary clinical care process. Examples of problems in support processes were unclear information provided to patients during preparation for routine examinations, or the identification of non-value-adding administrative activities in the physician workflow. In both examples, the processes addressed involved activities needed to support the patient care process, but that did not alone contribute to improvement of patients' health. Examples of problems related to technical/administrative processes dealt with infrastructures needed for the general functioning of the hospital, for example, the lack of available post-it notes for new improvement suggestions, or that the computers were not switched off during evening shifts. Examples of primary clinical processes addressed were poor pain-relief treatment for older patients and lack of standardised routines for central line placement in emergency care.

Complexity in issues addressed and in improvement actions proposed

A majority (89%) of the documents addressed problems and/or proposed suggestions that were categorised as simple (table 2). These were often small changes needed to the physical layout, for example changing the placement of medications to improve the ergonomic work environment for staff or fixing the lack of aprons and gloves in the storage area. By simply refilling the storage the risk for transmission of infections could be reduced. Complex issues included for example when staff members were feeling uncomfortable to collaborate across organisational boundaries or when staff at a unit complained about patients arriving from the emergency department that needed a quick transfer to the radiology unit.

Types of outcomes addressed and expected

In a majority of the cases (72%), operative outcomes were addressed. Staff proposed changes to work processes, physical layout or equipment that could yield improved quality of care for patients and a more efficient use of resources. Sociotechnical outcomes mentioned were staff well-being, suggested to be improved by for example increasing the indoor temperature in a perceived cold workplace.

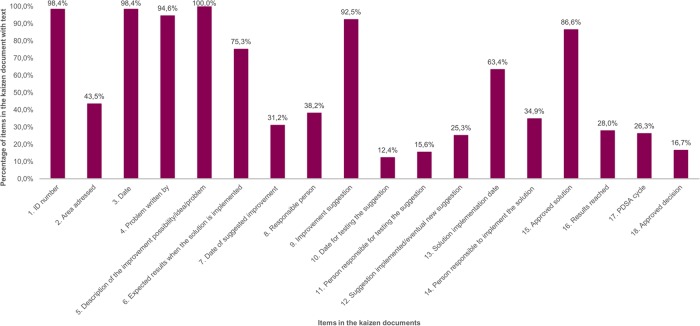

Degree of compliance to the kaizen documents

There was a large variation to what extent the different parts of the kaizen documents had been filled in. The percentage of compliance (ie, text filled in under each item in the template or marked in the PDSA phases) varied from 12% to 100% between the items (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Degree of compliance for each item in the kaizen documents (ie, percentage of the kaizen document that had text or markings in each one of the items).

The parts of the template that concerned problem identification and planning proposed solutions (items 2–9) had items with varied level of compliance. Items 3–6 (date, person who identified the problem, description of the improvement idea and expected result) and 9 (improvement suggestion) were characterised by a high degree of compliance, ranging from 75% to 98%. Items 2 (area addressed), 7 (date of suggested improvement) and 8 (person making the suggestion) were characterised by a lower degree of compliance, ranging from 32% to 44%.

Compliance was also low (12–25%) for items that concerned the test and further refinement of the improvement idea, and these items were number 10 (date for testing the suggestion), 11 (person responsible for testing the suggestion) and 12 (suggestion implemented). Compliance varied for items 13–18 that concerned the actual implementation of the solution and the monitoring of the results achieved. Information on the date for implementation (item 13) and the person responsible for the implementation (item 14) was provided in 63% and 35% of the kaizen documents, respectively. The final solution approved (item 15) was described in 87% of the documents, whereas the actual results achieved (item 16) were described in 28% of the cases. The solution was signed by and thereby approved by the managers (item 18) in 17% of the documents, which was however not a requirement for all types of suggestions. All the four phases of the PDSA cycle (item 17) were reported on in 25% of the documents, and in 49% at least one of the PDSA cycle's phases was mentioned.

Discussion

This study adds to the current knowledge on kaizen practices in healthcare by providing empirical evidence of when and how employees propose improvement ideas through an employee suggestion programme. The evidence was generated based on the analysis of a wide range of initiatives carried out at one hospital for a period of 1 year, rather than on single improvement initiatives as often reported in the literature. Kaizen templates were most often filled in when staff perceived a problem in support or technical/administrative processes. The problems addressed and the solutions proposed were often characterised by a low level of complexity and involved mainly operational aspects of performance. The degree of compliance with different parts of the kaizen template was generally high for items that concerned problem and solution identification and low for items corresponding to test and implementation of the solution. These findings will be discussed in relation to the literature on employee suggestion programmes, as well as the broader lean and kaizen literature.

The majority of the improvement ideas suggested by the employees in the kaizen templates were a reaction to an experienced problem. This can be related to the incremental approach to improvement that is inherent in kaizen practices. In other sectors, this incremental approach has been associated with reduced opportunities for innovation.12 28 Current research evidence however points to the fact that innovation and quality improvement can be handled in parallel.12 28 Further studies are needed to unravel the complex relationship between innovation and incremental improvement in healthcare and the practices needed to support this relationship.

The kaizen documents captured mainly simple improvement ideas that involved one organisational unit. The focus on single units may explain the scarcity of documents that addressed clinical care processes that often cross organisational boundaries. These findings suggest that, like at Toyota where lean and kaizen practices were developed, employee suggestion systems can be used to encourage employees to test and implement ideas that are within their immediate control. At Toyota, these systems do not however replace managers’ responsibility to solve more complex system-related problems.29 In healthcare, there are few examples of kaizen practices at the management level. An example is the creation of ad hoc management structures that cross organisational boundaries, which have proven to be effective to open up communication channels between hospital management and improvement teams.5 However, for healthcare organisations to achieve long-term results and to conduct improvement efforts that embrace a patient rather than a unit perspective, there is a need to develop kaizen practices at the management level that go beyond establishing communication channels.

For the type of outcomes addressed, most cases focused on the operational aspects of performance. Thus, there is a need for lean improvement efforts to embrace an employees' perspective to a larger extent.8–10 As lean transforms work structures and processes, its application in healthcare can be expected to affect the employees responsible for carrying out the work.9 As showed by previous studies of the same hospital, efforts to integrate operational and sociotechnical improvement activities with the kaizen system may lead to a better understanding of the relationship between work and health and a higher engagement in health promotion, as well as more engagement in using kaizen for improvement work in general.30 To achieve coherence among an organisation's improvement processes and its social, technical and structural systems is important when attempting to improve quality in healthcare organisations.31

The low degree of use of items in the kaizen documents that corresponded to test and evaluation of new ideas indicates that the scientific application of continuous improvement cycles was not optimal. Methods, such as PDSA cycles, that build on an iterative and scientific approach to improvement are seldom performed as planned in healthcare.13 The fact that this study was conducted 4 years after kaizen was introduced indicates that it is not merely a matter of time and experience with using kaizen. Without these components in place it can be difficult for organisations to monitor the results of improvement efforts and thus to motivate staff that their efforts actually yield the desired results. Nevertheless, in this setting, kaizen was still used despite this shortcoming, perhaps indicating that the system, even though mostly focusing on identification and suggestions for solutions, was perceived as valuable for staff.

Some variation in how the units used the kaizen templates was identified, although not explicitly explored in this study because of the limited number of documents collected from each unit. We observed for instance that more improvement suggestions were produced in small units. Close interaction among employees can help staff to do their work while also working constantly at improving it.5 Future studies can explore more in depth how contextual factors such as staff composition, turnover rates, stress level among staff and the organisation ability to implement the suggested ideas may influence staff participation in kaizen activities.

Strengths and limitations

The calculated frequencies and percentages are constructed from qualitative information in the kaizen documents in order to provide an overarching pattern and actual numbers shall be interpreted with caution. Some kaizen forms contained less information and this may have introduced some bias as they were more difficult to categorise. Nevertheless, using documents allowed us to track the written trails of improvements, thus providing information that is not limited by subjective experience or memory biases.

In the analysis, the information from multiple items was used to code the documents according to predefined categories and subcategories. This methodological choice enabled us to overcome the constraint of missing data in some of the items. However, if more documents were available, the separate analysis of some key items could have provided a more in-depth understanding of how kaizen works. The complexity aspect, for instance, could have been analysed separately for the issues addressed and the solutions proposed. Nevertheless, the choice to combine items can provide a holistic understanding of how kaizen documents are used.

Several measures were taken to strengthen the trustworthiness of the research process, such as having multiple researchers conducting the analysis based on clearly defined categories and subcategories. Nevertheless, a design that includes other sources of data (eg, interviews and observations) would have provided more insights. This data could include information on the actual implementation or lack thereof of changes suggested in kaizen documents and on possible contextual factors influencing kaizen practices.

The transferability of the findings is influenced by how kaizen practices were adopted at the studied hospital, which we thought to balance by providing a thorough description of the case.

Conclusions

Kaizen practices are mainly used by hospital staff in a reactive manner to address simple challenges rather than in a proactive manner or in relation to complex issues. Thus, there is a need to combine kaizen practices with improvement and innovation practices that help staff and managers to address more complex issues, such as the improvement of clinical care processes that cross organisational and institutional boundaries. Moreover, the limited focus on sociotechnical aspects and the partial compliance to the kaizen template, especially regarding test and implementation items, may indicate a limited understanding of the entire kaizen process and of how it relates to the overall organisational goals. This limited understanding can ultimately hamper the sustainability of kaizen practices themselves and of their results. It may also indicate that the simplicity of iterative approaches following the PDSA cycle is alluring, and that more efforts are needed in organisations to be able to continually improve.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the hospital for sharing their work on kaizen and Sandra Astnell for invaluable help in data transcription. This work was financially supported by AFA Insurance (grant no 110094). UvTS held a fellowship in improvement science funded by Vinnvård.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors designed the study. TS-H collected the data, PM and MEN conducted the analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors read, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Vinnvård Improvement Science Fellowship; AFA Försäkring (110094).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (ref no. 2011/1420-31/5).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Excel file with the qualitative directed content analysis is available by emailing pamela.mazzocato@ki.se.

References

- 1.Walshe K. Pseudoinnovation: The development and spread of healthcare quality improvement methodologies. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:153–9. 10.1093/intqhc/mzp012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radnor ZJ, Holweg M, Waring J. Lean in healthcare: the unfilled promise? Soc Sci Med 2012;74:364–71. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickson EW, Singh S, Cheung DS et al. Application of lean manufacturing techniques in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med 2009;37:177–82. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.11.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson GH, McCoin NS, Lescallette R et al. Kaizen: a method of process improvement in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:1341–9. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00580.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzocato P, Thor J, Bäckman U et al. Complexity complicates lean: lessons from seven emergency services. J Health Organ Manag 2014;28:266–88. 10.1108/JHOM-03-2013-0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen H, Røvik KA, Ingebrigtsen T. Lean thinking in hospitals: is there a cure for the absence of evidence? A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003873 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen H. How to design Lean interventions to enable impact, sustainability and effectiveness. A mixed-method study. J Hosp Adm 2015;4:18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzocato P, Savage C, Brommels M et al. Lean thinking in healthcare: a realist review of the literature. BMJ Qual Saf 2010;19:376–82. 10.1136/qshc.2009.037986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holden RJ. Lean Thinking in emergency departments: a critical review. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:265–78. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joosten T, Bongers I, Janssen R. Application of lean thinking to health care: issues and observations. Int J Qual Health Care 2009;21:341–7. 10.1093/intqhc/mzp036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandao de Souza L. Trends and approaches in lean healthcare. Leadersh Health Serv 2009;22:121–39. 10.1108/17511870910953788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palm K, Lilja J, Wiklund H. The challenge of integrating innovation and quality management practice. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell 2014:1–14. 10.1080/14783363.2014.939841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:290–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. LLC i. Six Sigma quality resources for achieving Six Sigma results dictionary. Secondary Six Sigma quality resources for achieving Six Sigma results dictionary. http://www.isixsigma.com/dictionary/kaizen/

- 15.Imai M. The key to Japan's competitive success. McGrow-Hill/Irwin, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahlstrom P. Lean service operations: translating lean production principles to service operations. Int J Serv Technol Manag 2004;5:545–64. 10.1504/IJSTM.2004.006284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suárez-Barraza MF, Miguel-Dávila JÁ. Assessing the design, management and improvement of Kaizen projects in local governments. Bus Process Manag J 2014;20:392–411. 10.1108/BPMJ-03-2013-0040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melnyk SA, Calantone RJ, Montabon FL et al. Short-term action in pursuit of long-term improvements: introducing Kaizen events. Prod Inventory Manag J 1998;39:69. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liker JK. The Toyota way: 14 management principles from the world's greatest manufacturer. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laraia AC, Moody PE, Hall RW. The kaizen blitz: accelerating breakthroughs in productivity and performance. John Wiley & Sons, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comtois J, Paris Y, Poder TG et al. [The organizational benefits of the Kaizen approach at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS)]. Sante Publique 2013;25:169–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farris JA. An empirical investigation of kaizen event effectiveness: outcomes and critical success factors. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deblois S, Lepanto L. Lean and Six Sigma in acute care: a systematic review of reviews. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2016;29:192–208. 10.1108/IJHCQA-05-2014-0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenfors-Hayes T, Hasson H, Augustsson H et al. Merging occupational health, safety and health promotion with lean: an integrated systems approach (the LeanHealth project). Creating Healthy Workplaces: Stress Reduction, Improved Well-Being and Organizational Effectiveness: Gower Applied Business Research, 2014:281–99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villa S. L'operations management a supporto del sistema di operazioni aziendali. Modelli di analisi e soluzioni progettuali per il settore sanitario [Healthcare operations management. Models of analysis and planning solutions for the healthcare sector] CEDAM, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:587–92. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paul Brunet A, New S. Kaizen in Japan: an empirical study. IJOPM 2003;23:1426–46. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marksberry P, Church J, Schmidt M. The employee suggestion system: a new approach using latent semantic analysis. Hum. Factors Ergon Manuf Serv Ind 2014;24:29–39 10.1002/hfm.20351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Thiele Schwarz U, Augustsson H, Hasson H et al. Promoting employee health by integrating health protection, health promotion, and continuous improvement: a longitudinal quasi-experimental intervention study. J Occup Environ Med 2015;57:217–25. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAlearney AS, Terris D, Hardacre J et al. Organizational coherence in health care organizations: conceptual guidance to facilitate quality improvement and organizational change. Qual Manag Health Care 2013;22:86–99. 10.1097/QMH.0b013e31828bc37d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]