Abstract

Objectives

To assess the performance of a 5-type human papillomavirus (HPV) messenger RNA (mRNA) test in primary screening within the framework of the Norwegian population-based screening programme.

Design

Nationwide register-based cohort study.

Setting

In 2003–2004, general practitioners and gynaecologists recruited 18 852 women for participation in a primary screening study with a 5-type HPV mRNA test.

Participants

After excluding women with a history of abnormal smears and with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2+) before or until 3 months after screening, 11 220 women aged 25–69 years were eligible for study participation. The Norwegian Cancer Registry completed follow-up of CIN2+ through 31 December 2009.

Interventions

Follow-up according to the algorithm for cytology outcomes in the population-based Norwegian Cervical Cancer Screening Programme.

Main outcome measures

We estimated cumulative incidence of CIN grade 3 or worse (CIN3+) 72 months after the 5-type HPV mRNA test.

Results

3.6% of the women were HPV mRNA-positive at baseline. The overall cumulative rate of CIN3+ was 1.3% (95% CI 1.1% to 1.5%) through 72 months of follow-up, 2.3% for women aged 25–33 years (n=3277) and 0.9% for women aged 34–69 years (n=7943). Cumulative CIN3+ rates by baseline status for HPV mRNA-positive and mRNA-negative women aged 25–33 years were 22.2% (95% CI 14.5% to 29.8%) and 0.9% (95% CI 0.4% to 1.4%), respectively, and 16.6% (95% CI 10.7% to 22.5%) and 0.5% (95% CI 0.4% to 0.7%), respectively, in women aged 34–69 years.

Conclusions

The present cumulative incidence of CIN3+ is similar to rates reported in screening studies via HPV DNA tests. Owing to differences in biological rationale and test characteristics, there is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity that must be balanced when decisions on HPV tests in primary screening are taken. HPV mRNA testing may be used as primary screening for women aged 25–33 years and 34–69 years.

Keywords: hpv mrna test, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, CIN3+, cervical cancer screening, hpv primary screening, hpv

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We consider studying primary screening with a 5-type human papillomavirus (HPV) messenger RNA (mRNA) test in a population of women with no previous cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and/or abnormal smears as a strength as the HPV infections diagnosed are likely to be ‘new’ infections.

We consider the follow-up within the Norwegian Cervical Cancer Screening Programme as strength, as women regardless of mobility within Norway, are captures by the surveillance system for cytology, histology and treatment.

We consider just having one screening round with the 5-type HPV mRNA test as a limitation, in addition to follow-up based on cytology only (verification bias).

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide.1 Cervical human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is necessary but not sufficient to cause cervical cancer.2 3 HPV is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections with a prevalence ranging from 20% to 30% in women aged 16–29 years.4 5 The lifetime risk of HPV infection in women is 70–80%.3

Approximately 15 HPV genotypes, referred to as high-risk (HR) types, are considered aetiological agents of cervical cancer.6 HPV16 is by far the most significant HPV type in persisting infection and promoting progression into high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or worse (CIN3+).7 8 Given the strong aetiological association between HR HPV infection and cervical cancer, HR HPV testing is considered an alternative for cytology-based cervical cancer screening.9

A review of seven randomised controlled trials (RCT) concluded that HPV testing in combination with cytology detected 67% more CIN3+ lesions in the first screening round compared with cytology-based screening alone for women aged 29 years and older (95% CI 1.27 to 2.19).10 In the second screening round, fewer CIN3+ lesions were detected in the HPV arm than in the cytology arm (risk ratio 0.49 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.66)). The cumulative CIN3+ detection rates over two screening rounds were not different (risk ratio 1.09 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.42)).10

The specificity of HPV DNA tests for CIN3+ is low, and the positive predictive value is low in groups with low CIN3+ incidence (eg, particularly young, sexually active women). The real cause of cervical cancer is not the HPV infection per se, but the continuous overexpression of the viral oncogenes E6 and E7 from oncogenic HPV types.11 There may be several reasons why E6 and E7 are overexpressed, but one of the main reasons is virus's integration into the human genome (loss of E2 gene results in loss of transcript regulation). The loss of the E2 gene only occurs in a small proportion of women with HPV infection.12 This implies that a test that detects the overexpression of E6 and E7 messenger RNA (mRNA) is more specific than a test that detects the presence of viral DNA. Not all cervical cancers have integrated viral forms; between 15% and 20% will have episomal forms only. Integration is not a requisite for transformation.13

HPV E6/E7 mRNA is a rational target for detecting HPV infections leading to cellular transformation. The HPV mRNA test PreTect HPV-Proofer detects E6/E7 mRNA of the five main HR HPV types, namely 16, 18, 31, 33 and 45, which are associated with 86% of cervical cancers in Europe.14 15 Owing to the higher specificity for CIN2+ of PreTect HPV-Proofer compared to other HPV tests,16–22 this test may have favourable characteristics in screening for cervical precancers. The aim of this study was to evaluate the performance of an HPV mRNA test in primary cervical cancer screening.

Material and methods

The study comprised 18 852 women aged 13–87 years visiting gynaecologists and general practitioners in different parts of Norway between 1 May 2003 and 31 December 2004. Women were included after an individual assessment by their physician.

The departments of pathology and microbiology, University Hospital of Northern Norway, Tromsø, organised the study. Within the study's legal framework, participant identification from the unique 11-digit personal identification number, kept by all Norwegian citizens, was merged with lifetime data on cervical cytology and histology in four national registries administered by the Norwegian Cancer Registry (NCR). With these mergers, a complete follow-up through 31 December 2009 was possible. A mandatory reporting on cancer to NCR has been practised since 1953, on cervical cytology since 1995 (1992) and on cervical histology since 2002 from all cytology/pathology laboratories. In addition, since 1997, gynaecology departments and practitioners collecting cervical biopsies/carrying out CIN treatment have been encouraged to report individual case report forms to NCR on CIN treatment.

In the merged data set, we excluded women with an abnormal smear history (n=4535) or a histology history of CIN2+ (n=871) prior to or until completion of 3 months (119 days) after the date of screening. In addition, we excluded women aged <25 years (n=2012) or >69 years (n=214). A total of 11 220 women aged 25–69 years in a situation resembling primary screening (table 1) were eligible.

Table 1.

Selection of study population

| N | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Eligible | 18 852 | |

| History of ASC-US/LSIL | 3218 | |

| History of HSIL | 1317 | |

| History of CIN1+ | 716 | |

| Age <25 years | 2012 | |

| Age ≥70 years | 214 | |

| CIN1+ at study start | 128 | |

| CIN1+ <120 days after study start | 27 | |

| In total | 7632 | |

| Study population | 11 220 |

ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; CIN1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Conventional pap tests and liquid-based cytology (LBC) were analysed in local cytology laboratories. In cases with conventional pap tests, extra specimen collections (PreTect TM) were made for HPV analysis. We extracted cervical cells from LBC by the ThinPrep 2000 (Cytyc Corporation, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA) for cytological examination. DNA/RNA was isolated from 5 mL of the leftover material of the LBC (or from the PreTect TM). All women were subjected to detection of HPV mRNA (PreTect HPV-Proofer, PreTect AS, Klokkarstua, Norway) in one laboratory. The HPV laboratory worked independently of the cytology departments, being unaware of the cytology results at the time of HPV detection and vice versa.

Biopsies were evaluated by pathologists and histological results were reported using CIN terminology.23 Pathology laboratories in Norway use the same classification system for cytology (Bethesda) and histology (CIN). Every year, all the laboratories receive reports from the NCR on laboratory-specific diagnostic performance. Annual meetings are held so cytologists and pathologist secure consistent classifications of diagnosis in cervical cancer prevention.

The national screening programme in Norway recommends all women aged 25–69 years to have cervical cytology (pap test) every third year. A national quality manual for cervical cancer prevention is continuously updated (http://www.kreftregisteret.no). Women with normal cytology are encouraged to do another screen within 3 years. Women with high-grade cytology (atypical squamous cells—cannot exclude highgrade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) (ASC-H/HSIL)) are referred immediately to colposcopy and biopsy. Prior to 2005, women with equivocal or low-grade cytology (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US/low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion LSIL)) were triaged by repeat cytology after 6 months. Women with repeated equivocal or low-grade cytology (ASC-US/LSIL×2) were triaged by repeat cytology after an additional 12 months. Women with persistent equivocal or low-grade cytology (ASC-US/LSIL×3) over a period of 18 months were referred to colposcopy and biopsy. Delayed HPV triage was implemented in the national screening programme in 2005. Women with ASC-US/LSIL were recommended repeat cytology and HPV testing after 6–12 months. Women with a positive HPV test and abnormal cytology were referred to colposcopy and biopsy. Women with a positive HPV test and normal cytology were retested after 12 months for persistence. Women with two consecutive positive HPV tests were referred for colposcopy and biopsy (http://www.kreftregisteret.no). The HPV tests used in Norway during 2005–2009 were Hybrid Capture II, PreTect HPV-Proofer and Amplicor.24

In Norway, the threshold for treatment by conization or large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) is CIN2. Outcome assessment was based on the histological result of biopsies, where CIN2+ was considered as the target disease and CIN1 and no CIN were considered as absence of disease. Only cervical cancer reported in the cancer file (validated by NCR against pathology reports at hospital) were true cases of cancer.

SPSS V.22 was used to conduct all statistical analyses, which entailed χ2 tests, Mann-Whitney tests and survival analyses. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, Region East, Oslo, Norway, reviewed the study. The committee approved merging the laboratory data on HPV and cytology/histology data from NCR without informed consent from the participants (REK Sør-Øst 2010/2858).

Results

At study start, the detection rate of HPV mRNA was 3.6% (n=399) among 11 220 women with no history of abnormal smears or history of abnormal cervical histology registered in NCR. Nearly half (189/399=47.4%) of the HPV-positive women were HPV16 positive. HPV16 was the single infection in 175 of 189 infections (92.3%) (tables 2 and 3). HPV45 was more prevalent than HPV18, HPV33 and HPV31. For all HPV types, the infection prevalence decreased significantly by age (tables 2 and 3) (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Prevalence of human papillomavirus at study start by age

| Age (years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 25–33 | 34–69 | Total | |

| N | 3277 | 7943 | 11 220 |

| HPV status | Per cent | Per cent | Per cent |

| HPV-negative | 92.9 | 97.9 | 96.4 |

| HPV31/33/45 (not 16, not 18) | 2.6 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| HPV18 (not 16) | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| HPV16 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 1.7 |

Table 3.

Cumulative proportion of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ and CIN3+ at 36 and 72 months by human papillomavirus status at baseline (95% CIs)

| |

36 months |

72 months |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

CIN2+ |

CIN2+ |

|||

| HPV status | N | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI |

| In total | 11 220 | 0.78 | 0.62 to 0.94 | 1.52 | 1.27 to 1.77 |

| HPV-negative | 10 821 | 0.28 | 0.20 to 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.58 to 0.96 |

| HPV-positive | 399 | 14.0 | 10.5 to 17.5 | 22.7 | 17.5 to 28.9 |

| HPV31/33/45 (not 16, not 18) | 152 | 9.2 | 4.6 to 13.8 | 16.3 | 8.4 to 24.2 |

| HPV18 (not 16) | 58 | 17.2 | 7.5 to 26.9 | 20.7 | 20.3 to 31.1 |

| HPV16 | 189 | 16.9 | 11.5 to 22.3 | 27.8 | 20.5 to 35.1 |

| |

CIN3+ |

CIN3+ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV status | N | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI |

| In total | 11 220 | 0.67 | 0.51 to 0.83 | 1.27 | 1.04 to 1.51 |

| HPV-negative | 10 821 | 0.28 | 0.20 to 0.40 | 0.62 | 0.46 to 0.79 |

| HPV-positive | 399 | 11.3 | 8.2 to 14.5 | 19.7 | 14.7 to 24.7 |

| HPV31/33/45 (not 16, not 18) | 152 | 7.2 | 3.1 to 11.3 | 14.3 | 6.7 to 21.9 |

| HPV18 (not 16) | 58 | 12.1 | 3.7 to 20.5 | 17.2 | 7.5 to 26.9 |

| HPV16 | 189 | 14.3 | 9.3 to 19.3 | 24.1 | 17.0 to 31.2 |

The 11 220 women were followed for 767 407 women months, with a mean of 68.4 months and a range of 4–80 months. During the study period of 80 months, 158 women (1.4%) developed CIN2+. The distribution of CIN2 relative to CIN3+ cases decreased by age (20% among women aged 25–33 years, 12% in women aged 34–69 years).

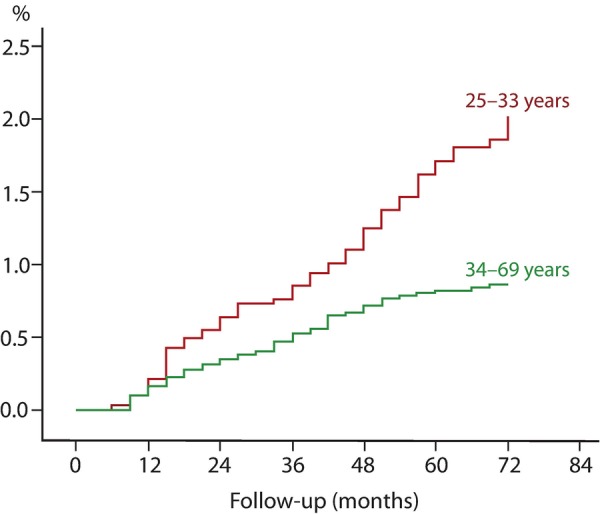

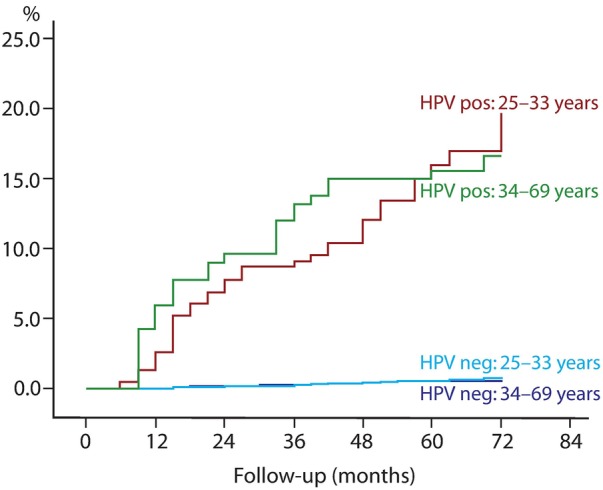

The cumulative proportions of both CIN2+ (table 3) and CIN3+ (table 3 and figure 1) were significantly higher in the younger (25–33 years) than older (34–69 years) women (survival analysis, p<0.001). At 36 and 72 months of follow-up, the cumulative proportions of CIN3+ were 0.95% (95% CI 0.62% to 1.28%) and 2.32% (95% CI 1.65% to 2.99%), respectively, for women aged 25–33 years, and 0.55% (95% CI 0.39% to 0.71%) and 0.87% (95% CI 0.65% to 1.09%), respectively, for women aged 34–69 years. After adjusting for HPV status at baseline, there were no differences in proportions of CIN2+ or CIN3+ (figure 2) between HPV-negative and HPV-positive women aged 25–33 or 34–69 years. However, HPV-positive women had significantly higher proportions of both CIN2+ and CIN3+ independent of age. The slope of the curve for proportions of CIN3+ (figure 2) among the younger HPV-positive women (25–33 years at baseline) increased linearly after 36 months, while the slope of the curve for proportions of CIN3+ among older women (34–69 years) levelled off (insignificant).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 or worse (CIN3+) by age.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 or worse (CIN3+) in human papillomavirus-positive and HPV-negative women by age.

The cumulative proportions of CIN2+ and CIN3+ at 36 and 72 months in women who were HPV positive or HPV-negative at baseline are displayed in table 3. In total, the cumulative proportions of CIN2+ or CIN3+ were significantly higher in women who were HPV16 positive at baseline compared to women who were HPV31/33/45 positive at baseline. There were no differences in CIN2+/CIN3+ between women who were HPV16 positive and women who were HPV18 positive at baseline. Owing to the small sample size, the same is the case between women who were HPV18 positive and women who were HPV31/33/45 positive at baseline (table 3). The slope of the curves, as displayed in figure 2, was similar across age (data not shown), but was inconsistently significant due to the small numbers. The cumulative proportions of CIN2+ and CIN3+ among HPV-negative women remained low throughout the study period (table 3 and figure 2).

All five cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed among women 40 years or older. One 42-year-old woman with HPV16 at baseline developed squamous cell carcinoma after 13 months. Another 42-year-old woman with HPV18 developed adenocarcinoma after 59 months. The three other cases were at ages 51, 57 and 59 years at baseline, were all HPV-negative and were diagnosed after 65, 22 and 33 months of observation—two adenocarcinomas and one squamous cell carcinoma. The cumulative incidence of cervical cancer was 47.0 (95% CI 5.8 to 88.2) per 100 000 women months at 72 months of observation (7.8/100 000 women per year).

Discussion

Our study examines a low-risk population as we excluded at study start all women with a history of abnormal cytology and/or histology from cervix uteri. These exclusions removed persistent HPV infections expressing on and off low-grade lesions over time, thus reducing HPV positivity. In addition, HPV positivity will be lower with an mRNA test targeting oncogenic expression, compared with a DNA test that detects HPV presence.

The present HPV mRNA positivity rate of 7.1% in women aged 25–33 years and 2.1% in women aged 34–69 years is much lower than those reported from studies using HPV DNA tests. In the Horizon study,25 across all age groups, 898 of 4413 (20.3%) samples were HPV DNA-positive (Cobas 4800, Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, California, USA) with normal cytology. This proportion decreased from 33.9% in women aged 23–29 years to 18.6% at age 30–39 years and 6.0% at age 50–65 years.25 This implies that HPV DNA primary screening in women younger than 40 years will lead to huge administrative challenges in the light of low incidence of cervical cancer. Cytology in triage of women with a positive HPV DNA test may reduce the burden of colposcopy, but triage-negative women still need follow-up.26 27 A woman with a positive HPV test has an increased risk of CIN3+ even though cytology is normal.27 28

The risks of CIN3+ after 36 months of follow-up were 0.67% overall and 0.28% in the HPV mRNA-negatives, a relative reduction of 58%. The risks of CIN3+ after 72 months of follow-up were 1.27% overall and 0.62% in the HPV mRNA-negatives, a relative reduction of 51%. Our results are in line with outcomes for primary screening with HPV DNA tests.7 29–31 A Danish study using Hybrid Capture 2, CIN3+ after 72 months of follow-up reported 2.0% overall and 1.0% in the HPV DNA-negatives, a relative reduction of 50%.7 In a US cohort of 20 810 women, HPV-negative/pap-negative women had a CIN3+ cumulative incidence rate of 0.16% after 45 months and 0.79% after 122 months.32 Similarly, in a German cohort of 4034 women, 0.7% of HPV-negative/pap-negative women developed CIN3+ during 5 years of follow-up.31 In a Dutch cohort of 2810 women, there was only one case of CIN3+ among women with negative results on both tests during 4.6 years of follow-up.29 In a US cohort of 19 512 women, a one-time negative HR-HPV test at enrolment provided greater reassurance over the 18-year follow-up than did a one-time negative pap against CIN2+ (1.85% vs 2.47%) and CIN3+ (0.90% vs 1.27%). In comparison, cumulative incidence was 1.73% for CIN2+ and 0.83% for CIN3+ after one-time HPV and pap tests that were both negative.30 In our study, the cumulative incidence of CIN3+ after 6 years was 1.3% for women with negative cytology and 0.6% for women with double negative cytology and HPV mRNA test, respectively. Since CIN3+ incidence depends on HPV prevalence, some heterogeneity between studies might be explained by differences in HPV prevalence and age at inclusion.

In a meta-analysis of European HPV primary studies, the cumulative incidence rate of CIN3+ after 6 years was considerably lower among women with a negative HPV at baseline 0.27%(95% CI 0.12% to 0.45%) than among women with negative results on cytology 0.97%(95% CI 0.53% to 1.34%). In comparison, the cumulative incidence rate for women with negative cytology results at the most commonly recommended screening interval in Europe (3 years) was 0.51% (95% CI 0.23% to 0.77%). The cumulative incidence rate among women with negative cytology results who were positive for HPV increased continuously over time, reaching 10% at 6 years, whereas the rate among women with positive cytology results who were negative for HPV remained below 3%.33

The HPV mRNA test employed in our study detects five HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, and 45) associated with 86% of cervical cancers in Europe.14 15 Women with other HPV types had a negative HPV mRNA test. Still, the cumulative risk of CIN3+ 6 years after a negative HPV mRNA test was low (0.62%). Most HPV DNA tests detect 13 or 14 HPV types. In a Danish study most of the HPV-positive CIN3+ cases were of HPV types 16, 18, 31 and 33.7 The cumulative risk of CIN3+ after 6 years in women with a positive HPV test of other HPV types was not significantly different from women with a negative Hybrid Capture 2.7 In Europe, HPV16 predominates in CIN3 and cervical cancer. Other HPV types have a slower progression into cancer.34 The risk of cervical cancer development is higher for HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33 and 45 than for other HPV types.35

It is important to improve the screening in young women. CIN3 detection from 25 years is important for decreasing the risk of cervical cancer, even in the postvaccinated era.36 In the Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) trial, more CIN3+ was found in women aged 25–29 years than in all women aged 40 years and older. Of all CIN3+ found in the study, 28% occurred among women aged 25–29 years, versus 25% in women aged 40 years or older.37

Over the past 20 years, Norway has witnessed an increase in cervical cancer rates in women younger than 40 years, despite cytology screening (http://www.kreftregisteret.no). In the USA, corroborating data from the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) tumor registry show a sharp rise in the incidence of invasive cervical cancer between the ages of 25 and 34 years (http://seer.cancer.gov, table 5.7). In the ATHENA study, 57.3% of women aged 25–29 years with CIN3+ had a negative cytology (NILM).37

In 2003/2004, there were no national guidelines for HPV testing and follow-up of HPV-positive women. Most CIN3+ cases were detected by passive follow-up in routine cervical cancer screening based on cytology every 3 years. This may result in verification bias favouring cytology when women with abnormal cytology were followed up, but not women with a positive HPV test.

Given that HPV mRNA-negative women retained their low risk of CIN3+ for at least 6 years, frequent screening of these women may be unnecessary. New HPV infections are associated with an extremely low risk of cancer because they usually resolve without the need for medical intervention.38

Conclusion

HPV mRNA testing may be used as primary screening for women aged 25–33 years and those aged 34–69 years. Studies designed to do ‘head-to-head’ comparison between HPV DNA and HPV mRNA tests in primary screening of CIN3+ are welcome.

Footnotes

Contributors: SWS, SF, TJG, ESM and FES contributed in the experiment conception and design. SWS, SF, TJG, ESM and FES were involved in experiment performance. SWS and FES were involved in data analysis. SWS, SF, TJG and ESM were involved in reagent/material/analysis tool. SWS and FES were the authors of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the University Hospital of North Norway (http://www.unn.no/).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, Region East, Oslo, Norway, reviewed the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. Anonymous individual-level data and the full data set are available at the University Hospital of North Norway by emailing the corresponding author (sveinung.sorbye@unn.no).

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86. 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;348:518–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa021641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 1999;189:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim S, Arduino JM, Roberts CC et al. Incidence and predictors of human papillomavirus-6,-11,-16, and-18 infection in young norwegian women. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:587–97. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820a9324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjaer SK, Chackerian B, van den Brule AJ et al. High-risk human papillomavirus is sexually transmitted: evidence from a follow-up study of virgins starting sexual activity (intercourse). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001;10:101–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitt M, Depuydt C, Benoy I et al. Multiple human papillomavirus infections with high viral loads are associated with cervical lesions but do not differentiate grades of cervical abnormalities. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:1458–64. 10.1128/JCM.00087-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjær SK, Frederiksen K, Munk C et al. Long-term absolute risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse following human papillomavirus infection: role of persistence. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1478–88. 10.1093/jnci/djq356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiffman M, Wentzensen N, Wacholder S et al. Human papillomavirus testing in the prevention of cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:368–83. 10.1093/jnci/djq562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014;383:524–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy J, Kennedy EB, Dunn S et al. HPV testing in primary cervical screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:443–52. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35241-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:342–50. 10.1038/nrc798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins SI, Constandinou-Williams C, Wen K et al. Disruption of the E2 gene is a common and early event in the natural history of cervical human papillomavirus infection: a longitudinal cohort study. Cancer Res 2009;69:3828–32. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arias-Pulido H, Peyton CL, Joste NE et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 integration in cervical carcinoma in situ and in invasive cervical cancer. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:1755–62. 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1755-1762.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbyn M, Castellsague X, de Sanjose S et al. Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Ann Oncol 2011;22:2675–86. 10.1093/annonc/mdr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:1048–56. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70230-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cattani P, Zannoni GF, Ricci C et al. Clinical performance of human papillomavirus E6 and E7 mRNA testing for high-grade lesions of the cervix. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:3895–901. 10.1128/JCM.01275-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lie AK, Risberg B, Borge B et al. DNA- versus RNA-based methods for human papillomavirus detection in cervical neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:908–15. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molden T, Kraus I, Karlsen F et al. Comparison of human papillomavirus messenger RNA and DNA detection: a cross-sectional study of 4,136 women >30 years of age with a 2-year follow-up of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:367–72. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molden T, Nygård JF, Kraus I et al. Predicting CIN2+ when detecting HPV mRNA and DNA by PreTect HPV-proofer and consensus PCR: A 2-year follow-up of women with ASCUS or LSIL pap smear. Int J Cancer 2005;114:973–6. 10.1002/ijc.20839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratnam S, Coutlee F, Fontaine D et al. Clinical performance of the PreTect HPV-Proofer E6/E7 mRNA assay in comparison with that of the Hybrid Capture 2 test for identification of women at risk of cervical cancer. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:2779–85. 10.1128/JCM.00382-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szarewski A, Ambroisine L, Cadman L et al. Comparison of predictors for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with abnormal smears. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:3033–42. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tropé A, Sjøborg K, Eskild A et al. Performance of human papillomavirus DNA and mRNA testing strategies for women with and without cervical neoplasia. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:2458–64. 10.1128/JCM.01863-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richart RM. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Pathol Annu 1973;8:301–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nygård M, Røysland K, Campbell S et al. Comparative effectiveness study on human papillomavirus detection methods used in the cervical cancer screening programme. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003460 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preisler S, Rebolj M, Untermann A et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in 5,072 consecutive cervical SurePath samples evaluated with the Roche cobas HPV real-time PCR assay. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e59765 10.1371/journal.pone.0059765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, van Kemenade FJ et al. Evaluation of 14 triage strategies for HPV DNA-positive women in population-based cervical screening. Int J Cancer 2012;130:602–10. 10.1002/ijc.26056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uijterwaal MH, Polman NJ, Van Kemenade FJ et al. Five-Year Cervical (Pre)Cancer Risk of Women Screened by HPV and Cytology Testing. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:502–8. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE et al. Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women who test pap-negative but are HPV-positive. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013;17(Suppl 1):S56–63. 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285437b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bulkmans NW, Rozendaal L, Voorhorst FJ et al. Long-term protective effect of high-risk human papillomavirus testing in population-based cervical screening. Br J Cancer 2005;92:1800–2. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castle PE, Glass AG, Rush BB et al. Clinical human papillomavirus detection forecasts cervical cancer risk in women over 18 years of follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3044–50. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoyer H, Scheungraber C, Kuehne-Heid R et al. Cumulative 5-year diagnoses of CIN2, CIN3 or cervical cancer after concurrent high-risk HPV and cytology testing in a primary screening setting. Int J Cancer 2005;116:136–43. 10.1002/ijc.20955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherman ME, Lorincz AT, Scott DR et al. Baseline cytology, human papillomavirus testing, and risk for cervical neoplasia: a 10-year cohort analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:46–52. 10.1093/jnci/95.1.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a1754 10.1136/bmj.a1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjalma WA, Fiander A, Reich O et al. Differences in human papillomavirus type distribution in high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cervical cancer in Europe. Int J Cancer 2013;132:854–67. 10.1002/ijc.27713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell N, Cuschieri K, Cubie H et al. Cervical cancers associated with human papillomavirus types 16, 18 and 45 are diagnosed in younger women than cancers associated with other types: a cross-sectional observational study in Wales and Scotland (UK). J Clin Virol 2013;58:571–4. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Blasio BF, Neilson AR, Klemp M et al. Modeling the impact of screening policy and screening compliance on incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in the post-HPV vaccination era. J Public Health (Oxf) 2012;34:539–47. 10.1093/pubmed/fds040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Behrens CM et al. The ATHENA human papillomavirus study: design, methods, and baseline results. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:46.e1–11. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiffman M, Wentzensen N. Human papillomavirus infection and the multistage carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013;22:553–60. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]