Abstract

Ultrasound is an established modality for shoulder evaluation, being accurate, low cost and radiation free. Different pathological conditions can be diagnosed using ultrasound and can be treated using ultrasound guidance, such as degenerative, traumatic or inflammatory diseases. Subacromial–subdeltoid bursitis is the most common finding on ultrasound evaluation for painful shoulder. Therapeutic injections of corticosteroids are helpful to reduce inflammation and pain. Calcific tendinopathy of rotator cuff affects up to 20% of painful shoulders. Ultrasound-guided treatment may be performed with both single- and double-needle approach. Calcific enthesopathy, a peculiar form of degenerative tendinopathy, is a common and mostly asymptomatic ultrasound finding; dry needling has been proposed in symptomatic patients. An alternative is represented by autologous platelet-rich plasma injections. Intra-articular injections of the shoulder can be performed in the treatment of a variety of inflammatory and degenerative diseases with corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid respectively. Steroid injections around the long head of the biceps brachii tendon are indicated in patients with biceps tendinopathy, reducing pain and humeral tenderness. The most common indication for acromion–clavicular joint injection is degenerative osteoarthritis, with ultrasound representing a useful tool in localizing the joint space and properly injecting various types of drugs (steroids, lidocaine or hyaluronic acid). Suprascapular nerve block is an approved treatment for chronic shoulder pain non-responsive to conventional treatments as well as candidate patients for shoulder arthroscopy. This review provides an overview of these different ultrasonography-guided procedures that can be performed around the shoulder.

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasound is an established and well-accepted modality for the evaluation of structures around the shoulder, being accurate, low cost and radiation free.1 A wide range of pathological conditions can be diagnosed using ultrasound, such as degenerative tendinopathy, calcific tendinopathy, partial- or full-thickness tears and subacromial–subdeltoid (SASD) bursitis. As the shoulder has a superficial anatomical position, it represents an excellent target to perform interventional procedures under ultrasound guidance. Thus, a number of pathological conditions can be treated using ultrasound as a guidance for needles.2 As ultrasound is an operator-dependent modality, both scanning and clinical expertise are essential to achieve good diagnostic accuracy.3

In this review article, we provide an overview of different ultrasound-guided procedures that can be performed around the shoulder.

SUBACROMIAL–SUBDELTOID BURSA INJECTIONS

The SASD bursa is a large synovial space that covers the whole rotator cuff like a cap, reducing local attrition and facilitating the movements of supraspinatus tendon underneath the acromion during arm abduction. It lies in the subacromial region, between the superior aspect of the supraspinatus tendon and the inferior surface of the acromion. When the rotator cuff is intact, this bursa does not communicate with the articular joint space.4 SASD bursitis is the most common finding on ultrasound evaluation for painful shoulder, a condition that may be due to primary or secondary causes.5 Primary, less common causes of bursitis are rheumatoid arthritis, gout, tuberculosis, polymyalgia rheumatica and other pathological conditions. Secondary inflammation may be related to rotator cuff degenerative disorders, such as tendinopathy or tears, as well as in the setting of anterosuperior impingement due to overhead activities. Isolated septic bursitis is uncommon, also after percutaneous procedures.6

Under normal conditions, the SASD bursa is collapsed and results are barely visible. In acute inflammation, ultrasound can demonstrate the presence of hypoanechoic effusion distending the hyperechoic bursal walls, whereas patients with chronic SASD bursitis present with thickened, hypoechoic bursal walls with or without effusion in between. Intrabursal injection for therapeutic purposes is usually performed with corticosteroids to reduce local inflammation and pain. It has been reported that subacromial steroid injection is effective up to 9 months and is superior to oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) administration.7 When combined with local anaesthetics it has been reported to favour steroid crystals precipitations, but evidence on this topic is still unclear.8

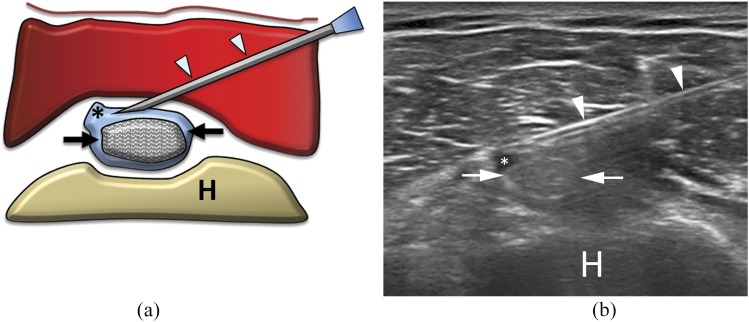

The patient may be seated on a table or in the supine position. After accurate disinfection of both the skin and the probe, a longitudinal ultrasound scan is obtained to visualize the SASD bursa. The needle is inserted with a lateral approach with respect to the probe. Once correct positioning of the needle tip has been achieved, the steroid can be injected into the bursa. The needle should not progress to pierce both sides of the bursa, as it can result in steroid leakage in the underlying rotator cuff tendons, possibly leading to tendon damage. After the procedure, the needle is removed and a plaster is applied at the puncture site together with an ice pack. No routine directions should be followed in the subsequent days. The procedure is shown in Figure 1.

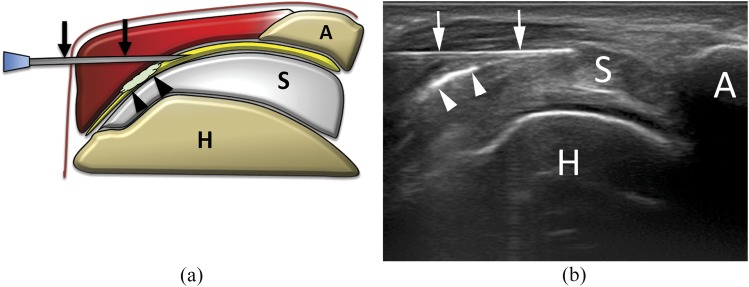

Figure 1.

(a) Scheme and (b) ultrasound image of subacromial–subdeltoid (SASD) bursa steroid injection. The needle (arrows) is inserted within the SASD bursa, filled with hyperechoic material (arrowheads) representing steroid solution. A, acromion; H, humerus; S, supraspinatus tendon.

TREATMENT OF CALCIFIC TENDINOPATHY OF THE ROTATOR CUFF

Calcific tendinopathy of rotator cuff refers to the intratendinous deposition of calcium, predominantly carbonate apatite.9 It is a common condition that occurs in up to 20% of painful shoulders and up to 7.5% of asymptomatic subjects, with females more frequently affected than males.10 Among the cuff tendons, supraspinatus is the more commonly affected (80% of cases), followed by infraspinatus and subscapularis (15% and 5% of cases, respectively), and is typically associated with a non-degenerative rotator cuff.11,12 Pathogenesis of calcific tendinopathy seems related to a combination of both microtraumatic factors and local decrease of oxygen concentration, with fibrocartilaginous metaplasia and tendon necrosis, followed by calcium hydroxyapatite crystal deposition.13 The resorption of the deposit is accompanied by acute inflammation (vascular invasion with migration of phagocytic cells and dissolution of the calcific focus), resulting in intratendinous oedema with sharp acute pain.14 Even if the condition is considered as self-healing (spontaneous resolution in 7–10 days), it may cause chronic moderate pain with functional disability.12 According to the ultrasound appearance, calcific deposits can be classified as hard (hyper-reflexive nodule with a well-circumscribed dorsal acoustic shadow), soft (well-circumscribed, homogeneous hyperechoic foci without posterior shadow) and fluid (hyperechoic peripheral rim with hypoechoic/anechoic centre).15–17

Being a self-healing process, asymptomatic cases of calcific tendinopathy do not usually require treatment. In patients with mild symptoms, the disease can be managed conservatively with physical therapy and a short course of oral NSAIDs.18 Lithotripsy has been demonstrated to be effective in selected cases.19 An effective alternative for symptomatic patients is to extract the calcific material using arthroscopy20 or an imaging-guided procedure.15,16,21–24 Ultrasound-guided percutaneous irrigation of calcific tendinopathy (US-PICT) is less invasive, quicker and with reduced post-procedural complication than arthroscopy.13 It has been reported to have an estimated average 55% pain improvement with 10% minor complication rate.25

US-PICT is always and immediately indicated in the acute phase of the pathology, with soft or fluid calcifications. In cases of mildly symptomatic hard calcifications, elective treatment should be considered.10,12 Percutaneous treatment is not indicated if the calcification is asymptomatic, is very small (<5 mm), has migrated into the bursal space or is eroding the humeral cortical bone.26

Since the first study performed by Farin et al, different techniques and approaches have been reported in the literature12,15,17,23,27,28 using one or two needles of different sizes to remove calcium. To date, no evidence exists in favour of using a specific size or number of needles.25

US-PICT is generally performed with patients in the supine position on a table. After sterile preparation of the skin and ultrasound probe, the target calcification is visualized along its major axis, while a small amount of local anaesthesia (up to 10 ml of lidocaine) is injected in the SASD bursa and around the calcification with an in-plane approach. A first needle is inserted into the lowest portion of the calcification with needle bevel open towards the probe. The second needle is then inserted into the calcification parallel and superficial to the first one, with its bevel opposite to the first needle in order to create a correct washing circuit.12,17 The calcification is then filled with saline solution, applying a gentle intermittent pressure in order to dissolve its core and allowing the chalky washing fluid to exit through the second needle, until a complete internal emptying is visualized.12,17 The procedure is then concluded with a SASD intrabursal steroid injection (40 mg methylprednisolone acetate). The whole procedure has an approximate duration of 15–20 min. Single-needle technique is very similar to what was reported above, with the exception that the calcification is punctured with one needle only. Washing is performed by pushing the syringe plunger to hydrate the deposit. Calcium refluxes back together with saline solution or anaesthetic within the same syringe as the plunger is released.23,24 Being less invasive, the single-needle technique has been thought to have a lower risk of infection and bleeding. Of note, the only case of septic bursitis after US-PICT ever reported6 happened after single-needle procedure. On the other hand, the use of two needles ensures an in–out flow of the saline solution outside the calcification, reducing the risk of calcification disruption and subsequent post-procedural bursitis.13,21 Double-needle procedure is shown in Figure 2 and single-needle procedure is shown in Figure 3.

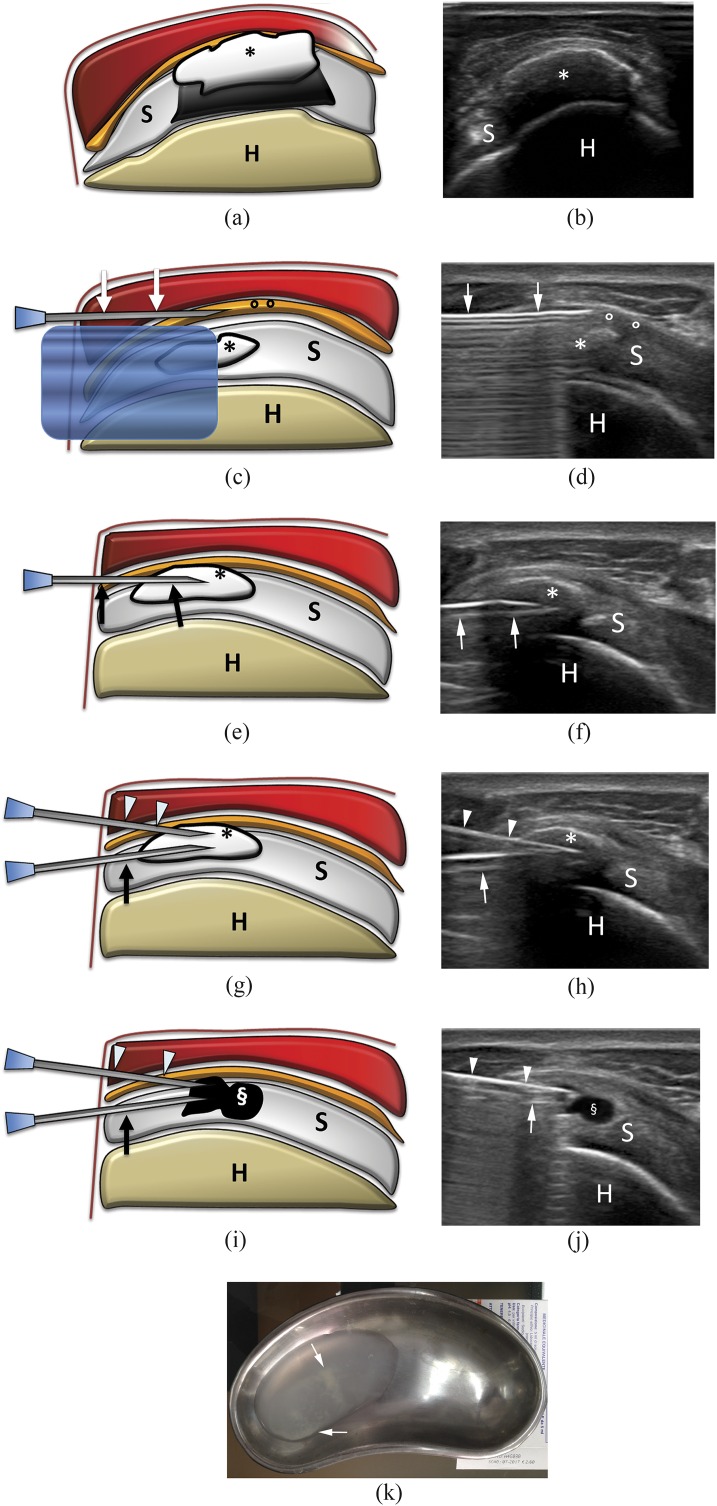

Figure 2.

Percutaneous treatment of calcific tendinopathy of the supraspinatus using double-needle technique. (a) Scheme and (b) ultrasound image of a hard calcification (asterisks) with acoustic back shadow. (c) Scheme and (d) ultrasound image of needle (arrows) insertion into the subacromial–subdeltoid bursa (circles) to inject anaesthesia. The calcification (asterisks) is visible under the reverberation artefact of the needle. (e) Scheme and (f) ultrasound image of first needle (arrows) insertion in the calcification (asterisks). Note that the bevel is open upward. (g) Scheme and (h) ultrasound image of the second needle (arrowheads) insertion in the calcification (asterisks) on the same coronal plane of the first needle (arrows). Note that the bevel of the second needle is open downward and that the back shadow of the more superficial needle partially covers the image of the deeper needle. (i) Scheme and (j) ultrasound image at the end of the procedure. The calcification is completely empty (§). (k) Saline used to wash a calcification with a double-needle procedure collected in a bowl. Note the whitish fragment of calcium dispersed in the solution (arrows). H, humerus; S, supraspinatus tendon.

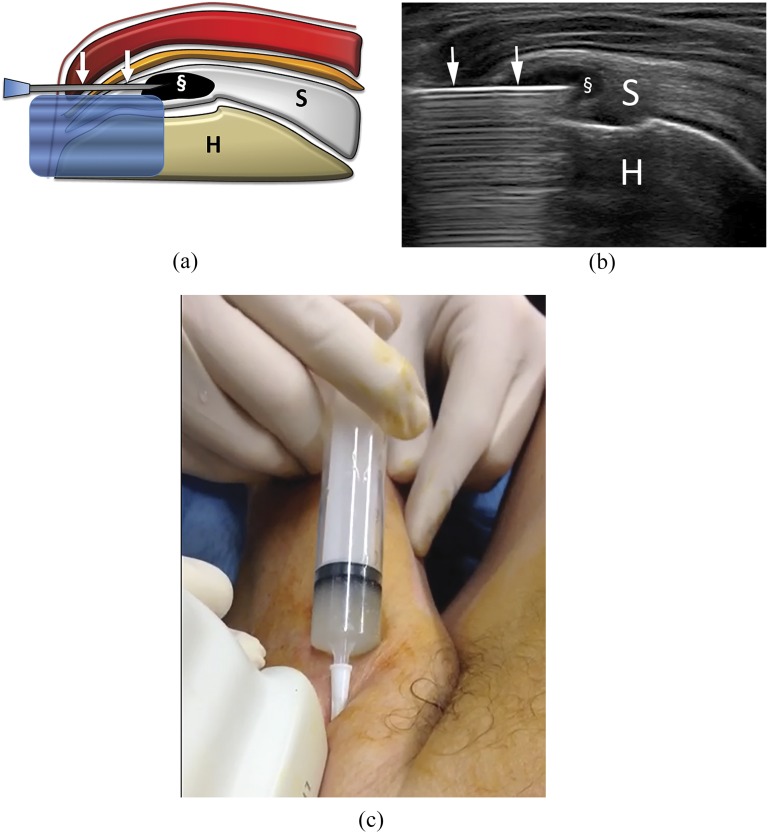

Figure 3.

Percutaneous treatment of calcific tendinopathy of the supraspinatus using single-needle technique. Bursa anaesthesia and needle insertion is similarly performed to what happens for double-needle procedure (Figures 2c–f). (a) Scheme and (b) ultrasound image at the end of the procedure performed with one needle (arrows). The calcification is completely empty (§). (c) Image taken during a single-needle procedure. The syringe is filled with whitish saline solution, containing the calcium that is being removed. Note that the luer is higher than the rest of the syringe, thus, allowing for calcium deposition on the bottom. H, humerus; S, supraspinatus tendon.

TREATMENT OF DEGENERATIVE TENDINOPATHY

Degenerative tendinopathy is characterized by structural degenerative changes of the collagen fibres with accompanying fibrosis, associated with minimal or no inflammation signs.29,30

Ultrasound appearance of degenerated tendons will show loss of the typical tendinous fibrillar echotexture and thickening of the affected tendon portion.31 A different form of degenerative tendinopathy is the so-called calcific enthesopathy, a very common and mostly asymptomatic ultrasound finding characterized by the presence of tiny hyperechoic calcifications at the insertional area of the rotator cuff tendons. This condition is frequently associated with degenerative alteration of the pre-insertional tendinous portion.32 Calcific enthesopathy is not a pathology itself but represents the deposition of calcium over a degenerated tendon matrix. Thus, it should not be confused with calcific tendinopathy, which is a totally different entity. Rotator cuff tendinopathy affects 1 out of 50 adults aged >65 years and usually presents with pain and reduced mobility.33

Different options have been reported to treat degenerative tendinopathy. Most of them are aimed to increase poor blood circulation within tendons, thus promoting autologous repair thanks to growth factors contained in platelets. Extracorporeal shockwaves have been used routinely, and a recent meta-analysis reported that they are safe and effective up to midterm.34 An alternative procedure is to perform dry needling of the tendon. It simply consists of a number of punctures performed preferably under ultrasound guidance on the degenerated area of the tendon, with the purpose of local bleeding. An alternative to simple dry needling is represented by autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP). It is a preparation of three components (platelet concentrate, cryoprecipitate of fibrinogen and thrombin) of whole blood withdrawn from the patient, containing growth factors and bioactive substances essential to musculoskeletal healing.35 Preparations of PRP are obtained from the transfusion medicine service of the hospital or prepared using disposable kits. Following activation with 1–2 ml of 10% calcium gluconate solution, autologous PRP must be injected immediately to prevent gelification.36

PRP has been suggested as a treatment option for various refractory tendinopathies37 including rotator cuff tendinopathy.38 In 2013, Scarpone et al39 conducted a prospective study on 45 subjects with refractory rotator cuff tendinopathy, concluding that a single intralesional injection of PRP under ultrasound guidance resulted in significant improvement in pain, function and MRI outcomes. Nevertheless, a recent review from Nourissat et al40 concluded that the available data do not support the use of PRP as a first-line treatment for chronic tendinopathy, regardless of lesion site and type. This aspect needs to be addressed before PRP can be used routinely.

After sterile preparation of both the skin and the ultrasound probe, the affected tendon is visualized with a longitudinal scan. A small amount of local anaesthetic is injected under ultrasound guidance into and under the SASD bursa. Then, consecutive dry-needling punctures are performed on the area of degenerated tendon fibres or also over the calcifications to fragment the small deposits and to produce slight bleeding into the insertional tendinous portion. The procedure can be finalized with the injection of 1 ml of steroid into the SASD. When PRP is used, about 5 ml can be slowly injected within the area of degenerated tendon fibres. The use of anaesthetic and steroid in conjunction with PRP is still debated.41

INTRA-ARTICULAR INJECTIONS AND HYALURONIC SUPPLEMENTATION OF THE SUBACROMIAL SPACE

Intra-articular injections of the shoulder can be performed in the treatment of a variety of pathological conditions. According to the pathology, the drug to be administered may be anti-inflammatory agents (such as steroids to treat different forms of adhesive capsulitis) or viscosupplements such as hyaluronic acid, injected in order to decelerate the physiological process of osteoarthritis.12,13

Adhesive capsulitis (or frozen shoulder) is a common disease that causes significant morbidity. It has an incidence of 3–5% in the general population and up to 20% in patients with diabetes, with a peak incidence in between the age of 40 and 60 years.42 The pathogenesis remains unclear but is thought to represent the final stage of a capsular chronic inflammatory process with abnormal tissue repair, leading to reduced capsular volume and restricted glenohumeral movements.12,42 Treatment includes conservative approaches with physical therapy, anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications. Intra-articular injections are indicated when oral treatment is not enough to improve the clinical outcome.43 Ultrasound-guided steroid injection may be considered in primary/secondary adhesive capsulitis with associated degenerative osteoarthritis and articular effusion.44 This treatment showed improvement in clinical outcome, both in terms of pain reduction and increased mobility.45 Another possibility is to obtain a capsular distension with lidocaine and hyaluronic acid; according to Park et al,46 this option is as effective as steroid injection in pain relief and functional improvement.

Intra-articular injection of hyaluronic acid is also indicated in degenerative osteoarthritis without articular effusion or when steroid injections are contraindicated such as in diabetes-related adhesive capsulitis.47 When conservative treatment fails, surgical approach with arthroscopic capsulotomy has to be considered.43

Intra-articular joint injections of the shoulder can be performed with either an anterior or a posterior approach. The posterior approach is generally more feasible, because the joint has a more superficial location with respect to the skin surface; also, with the anterior approach, the presence of the coracoid process can make it more difficult to visualize the needle tip.

Hyaluronic supplementation of the subacromial space is indicated in patients with cuff tear arthropathy, a condition in which shoulder osteoarthritis is associated with massive rotator cuff tear.48 In fact, this is a painful condition that leads to a progressive loss of function, weakness and diminished quality of life with difficulty in carrying out daily activities.12 Pharmacological treatment rests on oral NSAIDs, even though several possible complications may occur such as gastrointestinal bleeding, liver or kidney toxicity and cardiac disorders.49 Different surgical treatment options for cuff tear arthropathy have been proposed; however, in elderly patients, surgery may be more frequently associated with complications or may be precluded owing to concurrent medical conditions. According to Silverstein et al,50 supplementation with hyaluronic acid can help in the conservative management of this condition. The treatment with three consecutive hyaluronic acid injections per week improves the clinical scores and achieves pain relief at 6-month follow-up.50

Ultrasound guidance is highly recommended since blind injection is associated with high failure rate.13 The access to the subacromial space is visualized on a coronal ultrasound scan. With an in-plane approach, the needle is advanced to reach the space, and 6 ml of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid is attached to the needle. The treatment should be repeated after 1 week.

A prospective open-label non-randomized trial from Tagliafico et al focused on elderly patients with massive rotator cuff tear showed significant improvement of the pain and mobility scores in the first 4 months of follow-up in the treated patients, but not in the control subjects. Of note, after 5 months, the outcome of treated and non-treated patients was not different.48 Thus, authors concluded that ultrasound-guided viscosupplementation represents a beneficial therapeutic option in the first months of treatment.48 The procedure is shown in Figure 4.

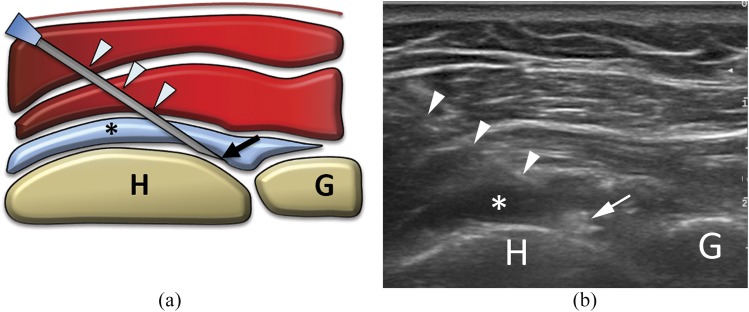

Figure 4.

(a) Scheme and (b) ultrasound image of glenohumeral intra-articular injection with posterior approach. The needle (arrowheads) is inserted with lateral, in-plane approach to place the tip (arrows) within the joint capsule (here already distended by some fluid; asterisks). G, glenoid; H, humerus.

LONG HEAD OF THE BICEPS BRACHII TENDON INJECTION

Injection around the long head of the biceps brachii tendon (LHBBT) is indicated in patients with biceps tendinopathy, which refers to a spectrum of pathologies ranging from inflammatory tenosynovitis (with synovial sheath effusion and hypertrophy) to degenerative tendinosis.51 Tenosynovitis can be found alone even if usually it is associated with rotator cuff tear, as the glenohumeral joint communicates with the LHBBT sheath (secondary tenosynovitis).2

The presence of a small amount of fluid within LHBBT sheath is a common finding and is often asymptomatic, being associated with glenohumeral effusion. Conversely, conspicuous effusion is usually symptomatic. Patients with inflammatory tenosynovitis present with pain that originates from the anterior surface of the shoulder and irradiates along the humerus.51

Ultrasound can easily detect the presence of anechoic fluid effusion around the tendon in both axial and longitudinal scan. Furthermore, ultrasound is useful for the differential diagnosis of complete rupture, subluxation and dislocation of LHBBT.12

Rest, physiotherapy and NSAIDs represent the first-line conservative management. In the acute phase, percutaneous steroid injection may help in reducing pain and humeral tenderness. In the presence of a large amount of fluid inside the sheath, aspiration should be performed before drug injection.51

For the percutaneous procedure, the LHBBT is examined on axial scan along its whole extent, in order to identify the level of larger effusion. Colour Doppler can be used to identify the anterior circumflex artery, to avoid puncturing it. The needle is inserted with an in-plane approach lateral to the probe and advanced towards the tendon and the drug is injected within the sheath, taking care to avoid tendon penetration. The procedure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

(a) Scheme and (b) ultrasound image of long head of biceps tendon sheath injection. The needle (arrowheads) is inserted with lateral, in-plane approach to place the tip within the tendon sheath (here already distended by some fluid; asterisks). Note that the underlying biceps tendon (arrows) has been carefully avoided. H, humerus.

ACROMION–CLAVICULAR JOINT INJECTION

The most common indication for acromion–clavicular (AC) joint injection is degenerative osteoarthritis, a very common pathology among elderly individuals owing to degeneration of the fibrocartilaginous disc that cushions articular surfaces.52 Osteoarthritis of the AC joint is a common source of pain, usually presenting with insidious onset and occurring with active/passive abduction of the shoulder.53 Often presenting in association with degenerative shoulder arthropathy, this condition may be confused with rotator cuff pathology, so history and a thorough physical examination are extremely important in diagnosing this condition. On physical examination, there is tenderness to palpation of the AC joint; a bump over the joint space indicates the possible presence of a cyst arising from the articular capsule.2 Conventional radiography helps to establish the proper diagnosis, with joint narrowing and prominent AC joint osteophytes as typical X-ray findings.13 Ultrasound will highlight the presence of irregular cortical profile of the AC joint bone surfaces, with possible association of capsular thickening and joint effusion. Ultrasound is also useful for obtaining a precise localization of the joint space.12

Physiotherapy represents the first treatment option. In cases of persisting pain condition, steroids, lidocaine or hyaluronic acid injections are helpful in improving clinical outcome, especially in the first week after therapy.12 A prospective and randomized study by Sabeti-Aschraf et al54 showed significant clinical improvement in pain and function up to 1 week post injection, with ultrasound guidance allowing for an easier procedure than blind injection.

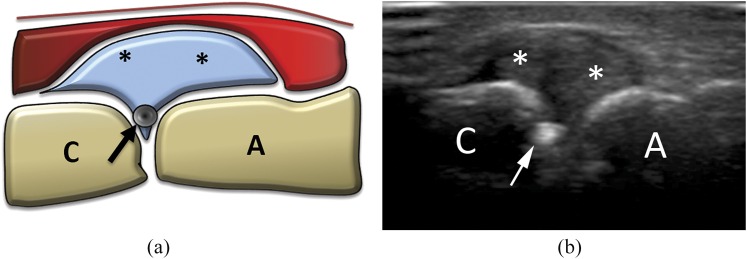

To perform this procedure, the patient is seated opposite to the examiner in a neutral position, with the hand lying on the thigh. Both in-plane and out-of-plane techniques can be used, but the last approach is preferred owing to the very superficial position of the AC joint. A coronal scan of the AC joint is then obtained, and the needle is inserted perpendicularly to the skin at the exact half of the probe. A clear sensation of resistance should be appreciated as the joint capsule is passed. No resistance should be encountered during injection if the needle tip is placed correctly; a successful injection is indicated by the capsule and joint space widening that can be seen under real-time scanning. The procedure is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a) Scheme and (b) ultrasound image of acromion–clavicular joint injection. Being inserted with co-axial, out-of-plane approach, only the needle tip (arrows) is visible. A, acromion; asterisk, joint capsule with synovial hypertrophy; C, clavicle.

SUPRASCAPULAR NERVE BLOCK

The suprascapular nerve is a mixed nerve that accounts for 70% of shoulder joint sensitivity, mainly innervating the posterior and superior capsules. It originates from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus (C5 and C6 roots) and descends through the suprascapular foramen to enter in the fossa supraspinata, providing sensory branches to the glenohumeral joint, AC joint, subacromial bursa and coracoclavicular ligament. Motor branches are provided for the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.12,59

Suprascapular nerve block (SSNB) performed under ultrasound guidance is a safe technique that allows for relieving pain given by different shoulder conditions. It is mainly aimed to treat patients with degenerative changes, but it can be helpful also in patients with rheumatological conditions or post-operative pain.55 The technique was first described by Wertheim and Rovenstine in 194156 but has increased in popularity after the first descriptions of ultrasound anatomy of the suprascapular region relevant to SSNB and the ultrasound-guided block technique.57,58 When performed under ultrasound guidance, the incidence of potential complications (e.g., pneumothorax, infraspinatus muscle pseudoparalysis and nerve damage) is reported to be very low.55,60

The nerve can be blocked at two different sites: superiorly, as it passes into the coracoid notch, and posteriorly, when passing into the spinoglenoid notch. When the nerve is blocked at the coracoid notch, both fibres for the supraspinatus and infraspinatus are involved, while a block performed at the spinoglenoid notch involves the fibres for the infraspinatus only.

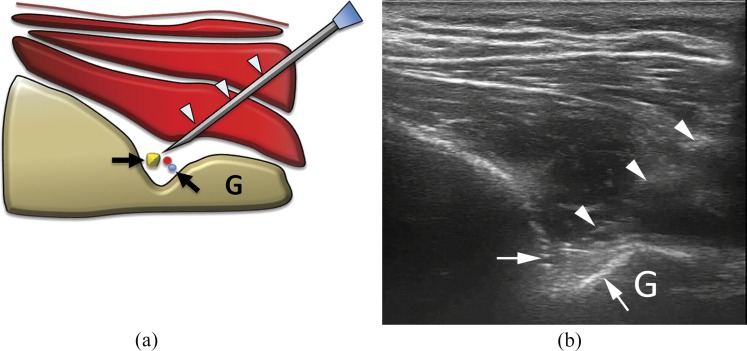

Different approaches may be used to perform ultrasound-guided SSNB. We prefer to place the patient lying prone on the bed to avoid possible vagal reaction. The easiest method is to obtain a transverse scan of the scapular spine (that can be identified with palpation) and then of the spinoglenoid notch. The use of colour Doppler may be useful at this stage to identify suprascapular artery, usually coursing medially to the nerve. From this site, the nerve can be then easily tracked up to the coracoid notch. Whatever location is chosen to block, a needle is then positioned in the notch around the nerve with an in-plane approach. Intranerve injection should be avoided to prevent nerve damage. Because of close proximity of the artery, colour Doppler may help to avoid intra-arterial needle insertion. Also, aspiration before injection helps to double-check needle positioning. Up to 8 ml of long-lasting anaesthetic (mepivacaine or bupivacaine 2%) can be used. The procedure is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

(a) Scheme and (b) ultrasound image of suprascapular nerve block at the spinoglenoid notch. The needle (arrowheads) is inserted with lateral, in-plane approach to place the tip around the spinoglenoid notch (arrows), where the suprascapular neurovascular bundle runs. As the bundle is barely visible, particular caution should be taken when performing this procedure. G, glenoid.

CONCLUSION

To summarise, ultrasound procedures around the shoulder can be performed to treat a number of different pathological conditions. In some cases, such as calcific or degenerative tendinopathy, these procedures have the purpose of completely treating the disease. In other cases, the treatment may be aimed to slow down the degenerative process that naturally affects the shoulder in elderly subjects. Whatever the purpose, these treatments have the common features of not being very invasive. They are also extremely cheap, both in terms of raw cost and in terms of time and discomfort burden for patients. Thus, they should be regarded as an effective, first-line approach to a number of pathologies around the shoulder.

Contributor Information

Carmelo Messina, Email: carmelomessina.md@gmail.com.

Giuseppe Banfi, Email: banfi.giuseppe@unisr.it.

Davide Orlandi, Email: theabo@libero.it.

Francesca Lacelli, Email: lafrancy78@libero.it.

Giovanni Serafini, Email: giovanni.serafini52@gmail.com.

Giovanni Mauri, Email: vanni.mauri@gmail.com.

Francesco Secchi, Email: francescosecchimd@gmail.com.

Enzo Silvestri, Email: silvi.enzo@gmail.com.

Luca Maria Sconfienza, Email: io@lucasconfienza.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corazza A, Orlandi D, Fabbro E, Ferrero G, Messina C, Sartoris R, et al. Dynamic high-resolution ultrasound of the shoulder: how we do it. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 266–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sconfienza LM, Serafini G, Silvestri E, eds. Ultrasound-guided musculoskeletal procedures: the upper Limb. Milan, Italy: Springer-Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobson JA. Shoulder US: anatomy, technique, and scanning pitfalls. Radiology 2011; 260: 6–16. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bureau NJ, Dussault RG, Keats TE. Imaging of the bursae around the shoulder joint. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25: 513–17. doi: 10.1007/s002560050127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Holsbeeck M, Strouse PJ. Sonography of the shoulder: evaluation of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993; 160: 561–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.3.8430553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sconfienza LM, Randelli F, Sdao S, Sardanelli F, Randelli P. Septic bursitis after ultrasound-guided percutaneous treatment of rotator cuff calcific tendinopathy. PM R 2014; 6: 746–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulder: a meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2005; 55: 224–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson J, Jayaraman S. Guided interventions in musculoskeletal ultrasound: what's the evidence? Clin Radiol 2011; 66: 140–52. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speed CA, Hazleman BL. Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1582–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905203402011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serafini G, Sconfienza LM, Lacelli F, Silvestri E, Aliprandi A, Sardanelli F. Rotator cuff calcific tendonitis: short-term and 10-year outcomes after two-needle us-guided percutaneous treatment–nonrandomized controlled trial. Radiology 2009; 252: 157–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2521081816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uhthoff HK, Sarkar K. Calcifying tendinitis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 1989; 3: 567–81. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3579(89)80009-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bianchi S, Martinoli C, eds. Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagliafico A, Russo G, Boccalini S, Michaud J, Klauser A, Serafini G, et al. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures around the shoulder. Radiol Med 2014; 119: 318–26. doi: 10.1007/s11547-013-0351-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Carli A, Pulcinelli F, Rose GD, Pitino D, Ferretti A. Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Joints 2014; 2: 130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farin PU, Jaroma H, Soimakallio S. Rotator cuff calcifications: treatment with US-guided technique. Radiology 1995; 195: 841–3. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.3.7754018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farin PU, Räsänen H, Jaroma H, Harju A. Rotator cuff calcifications: treatment with ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle aspiration and lavage. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25: 551–4. doi: 10.1007/s002560050133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sconfienza LM, Bandirali M, Serafini G, Lacelli F, Aliprandi A, Di Leo G, et al. Rotator cuff calcific tendinitis: does warm saline solution improve the short-term outcome of double-needle US-guided treatment? Radiology 2012; 262: 560–6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11111157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurt G, Baker CL, Jr. Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am 2003; 34: 567–75. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00089-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu CJ, Wang DY, Tseng KF, Fong YC, Hsu HC, Jim YF. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jerosch J, Strauss JM, Schmiel S. Arthroscopic treatment of calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1998; 7: 30–7. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90180-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sconfienza LM, Serafini G, Sardanelli F. Treatment of calcific tendinitis of the rotator cuff by ultrasound-guided single-needle lavage technique. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197: W366. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradley M, Bhamra MS, Robson MJ. Ultrasound guided aspiration of symptomatic supraspinatus calcific deposits. Br J Radiol 1995; 68: 716–19. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-68-811-716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aina R, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ, Aubin B, Brassard P. Calcific shoulder tendinitis: treatment with modified US-guided fine-needle technique. Radiology 2001; 221: 455–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2212000830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sconfienza LM, Viganò S, Martini C, Aliprandi A, Randelli P, Serafini G, et al. Double-needle ultrasound-guided percutaneous treatment of rotator cuff calcific tendinitis: tips & tricks. Skeletal Radiol 2013; 42: 19–24. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1462-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanza E, Banfi G, Serafini G, Lacelli F, Orlandi D, Bandirali M, et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous irrigation in rotator cuff calcific tendinopathy: what is the evidence? A systematic review with proposals for future reporting. Eur Radiol 2015; 25: 2176–83. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3567-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serafini G, Sconfienza LM. Treatment of calcific tendinitis of the rotator cuff. In: Silvestri E, Muda A, Sconfienza LM. eds. Normal ultrasound anatomy of the musculoskeletal system: a practical guide. Milan, Italy: Springer-Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.del Cura JL, Torre I, Zabala R, Legórburu A. Sonographically guided percutaneous needle lavage in calcific tendinitis of the shoulder: short- and long-term results. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 189: W128–34. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cacchio A, Rompe JD, Serafini G, Sconfienza LM, Sardanelli F. US-guided percutaneous treatment of shoulder calcific tendonitis: some clarifications are needed. Radiology 2010; 254: 990. doi: 10.1148/radiol.091542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rees JD, Wilson AM, Wolman RL. Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006; 45: 508–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2009; 43: 236–41. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papatheodorou A, Ellinas P, Takis F, Tsanis A, Maris I, Batakis N. US of the shoulder: rotator cuff and non-rotator cuff disorders. Radiographics 2006; 26: e23. doi: 10.1148/rg.e23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slobodin G, Rozenbaum M, Boulman N, Rosner I. Varied presentations of enthesopathy. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007; 37: 119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brox JI. Regional musculoskeletal conditions: shoulder pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003; 17: 33–56. doi: 10.1016/S1521-6942(02)00101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louwerens JK, Sierevelt IN, van Noort A, van den Bekerom MP. Evidence for minimally invasive therapies in the management of chronic calcific tendinopathy of the rotator cuff: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 1240–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molloy T, Wang Y, Murrell G. The roles of growth factors in tendon and ligament healing. Sports Med 2003; 33: 381–94. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333050-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, Nurden P, Nurden AT. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost 2004; 91: 4–15. doi: 10.1267/THRO04010004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrero G, Fabbro E, Orlandi D, Martini C, Lacelli F, Serafini G, et al. Ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma in chronic Achilles and patellar tendinopathy. J Ultrasound 2012; 15: 260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy: a model for the continuum of pathology and related management. Br J Sports Med 2010; 44: 918–23. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.054817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scarpone M, Rabago D, Snell E, Demeo P, Ruppert K, Pritchard P, et al. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injection for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a prospective open-label study. Glob Adv Health Med 2013; 2: 26–31. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2012.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nourissat G, Ornetti P, Berenbaum F, Sellam J, Richette P, Chevalier X. Does platelet-rich plasma deserve a role in the treatment of tendinopathy? Joint Bone Spine 2015; 82: 230–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bausset O, Magalon J, Giraudo L, Louis ML, Serratrice N, Frere C, et al. Impact of local anaesthetics and needle calibres used for painless PRP injections on platelet functionality. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2014; 4: 18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson CM, Seah KT, Chee YH, Hindle P, Murray IR. Frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94: 1–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.27093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uppal HS, Evans JP, Smith C. Frozen shoulder: a systematic review of therapeutic options. World J Orthop 2015; 6: 263–8. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i2.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (1): CD004016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juel NG, Oland G, Kvalheim S, Løve T, Ekeberg OM. Adhesive capsulitis: one sonographic-guided injection of 20 mg triamcinolon into the rotator interval. Rheumatol Int 2013; 33: 1547–53. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2503-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park KD, Nam HS, Lee JK, Kim YJ, Park Y. Treatment effects of ultrasound-guided capsular distension with hyaluronic acid in adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abate M, Pulcini D, Di Iorio A, Schiavone C. Viscosupplementation with intra-articular hyaluronic acid for treatment of osteoarthritis in the elderly. Curr Pharm Des 2010; 16: 631–40. doi: 10.2174/138161210790883859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tagliafico A, Serafini G, Sconfienza LM, Lacelli F, Perrone N, Succio G, et al. Ultrasound-guided viscosupplementation of subacromial space in elderly patients with cuff tear arthropathy using a high weight hyaluronic acid: prospective open-label non-randomized trial. Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 182–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1894-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bloom BS. Direct medical costs of disease and gastrointestinal side effects during treatment for arthritis. Am J Med 1988; 84: 20–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silverstein E, Leger R, Shea KP. The use of intra-articular hylan G-F 20 in the treatment of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the shoulder: a preliminary study. Am J Sports Med 2007; 35: 979–85. doi: 10.1177/0363546507300256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, Provencher MT, Mazzocca AD, Verma NN, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2010; 18: 645–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mall NA, Foley E, Chalmers PN, Cole BJ, Romeo AA, Bach BR, Jr. Degenerative joint disease of the acromioclavicular joint: a review. Am J Sports Med 2013; 41: 2684–92. doi: 10.1177/0363546513485359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menge TJ, Boykin RE, Bushnell BD, Byram IR. Acromioclavicular osteoarthritis: a common cause of shoulder pain. South Med J 2014; 107: 324–9. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sabeti-Aschraf M, Ochsner A, Schueller-Weidekamm C, Schmidt M, Funovics PT, V Skrbensky G, et al. The infiltration of the AC joint performed by one specialist: ultrasound versus palpation a prospective randomized pilot study. Eur J Radiol 2010; 75: e37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng PW, Wiley MJ, Liang J, Bellingham GA. Ultrasound-guided suprascapular nerve block: a correlation with fluoroscopic and cadaveric findings. Can J Anaesth 2010; 57: 143–8. doi: 10.1007/s12630-009-9234-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wertheim HM, Rovenstine EA. Suprascapular nerve block. Anesthesiology 1941; 2: 541–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-194109000-00006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harmon D, Hearty C. Ultrasound-guided suprascapular nerve block technique. Pain Physician 2007; 10: 743–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yücesoy C, Akkaya T, Ozel O, Cömert A, Tüccar E, Bedirli N, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation and morphometric measurements of the suprascapular notch. Surg Radiol Anat 2009; 31: 409–14. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0458-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vorster W, Lange CP, Briët RJ, Labuschagne BC, du Toit DF, Muller CJ, et al. The sensory branch distribution of the suprascapular nerve: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 500–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu SS, Gordon MA, Shaw PM, Wilfred S, Shetty T, Yadeau JT. A prospective clinical registry of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia for ambulatory shoulder surgery. Anesth Analg 2010; 111: 617–23. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ea5f5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]