Abstract

Objective:

While haemangiomas are common benign vascular lesions involving the spine, some behave in an aggressive fashion. We investigated the utility of fat-suppressed sequences to differentiate between benign and aggressive vertebral haemangiomas.

Methods:

Patients with the diagnosis of aggressive vertebral haemangioma and available short tau inversion-recovery or T2 fat saturation sequence were included in the study. 11 patients with typical asymptomatic vertebral body haemangiomas were selected as the control group. Region of interest signal intensity (SI) analysis of the entire haemangioma as well as the portion of each haemangioma with highest signal on fat-saturation sequences was performed and normalized to a reference normal vertebral body.

Results:

A total of 8 patients with aggressive vertebral haemangioma and 11 patients with asymptomatic typical vertebral haemangioma were included. There was a significant difference between total normalized mean SI ratio (3.14 vs 1.48, p = 0.0002), total normalized maximum SI ratio (5.72 vs 2.55, p = 0.0003), brightest normalized mean SI ratio (4.28 vs 1.72, p < 0.0001) and brightest normalized maximum SI ratio (5.25 vs 2.45, p = 0.0003). Multiple measures were able to discriminate between groups with high sensitivity (>88%) and specificity (>82%).

Conclusion:

In addition to the conventional imaging features such as vertebral expansion and presence of extravertebral component, quantitative evaluation of fat-suppression sequences is also another imaging feature that can differentiate aggressive haemangioma and typical asymptomatic haemangioma.

Advances in knowledge:

The use of quantitative fat-suppressed MRI in vertebral haemangiomas is demonstrated. Quantitative fat-suppressed MRI can have a role in confirming the diagnosis of aggressive haemangiomas. In addition, this application can be further investigated in future studies to predict aggressiveness of vertebral haemangiomas in early stages.

INTRODUCTION

Vertebral haemangiomas are common vascular lesions affecting 11% of the population according to autopsy series.1 These lesions are usually asymptomatic and are discovered as incidental findings on multiple imaging modalities. Nevertheless, in some instances, these lesions can behave aggressively and cause pain or neurological deficit secondary to expansion of the vertebral body or paravertebral or epidural soft-tissue extension with spinal cord/nerve root compression.2–4

Histologically, haemangiomas are predominantly composed of vascular lined spaces and non-vascular components that may include adipose tissue, smooth muscle, fibrous tissue, bone, haemosiderin and thrombus.2 There are two histological subtypes of haemangioma: the cavernous type which is the most common subtype and is characterized by large sinusoidal spaces, and the capillary type which demonstrates smaller vascular channels.5,6 Vertebral haemangiomas classically have a coarse, vertical, trabecular pattern on radiographs which are seen on axial CT scan as punctate areas of sclerosis on axial imaging called “polka-dot” appearance or “jail-bar”, or “corduroy-cloth appearance” on sagittal or coronal reconstructions.7 On MRI imaging, the signal intensity (SI) of typical asymptomatic haemangiomas is usually increased on both T1 and T2 weighted sequences; however, aggressive haemangiomas have been shown to have low T1 SI related to paucity of adipose tissue.6,7 The presence of adipose tissue in haemangiomas therefore has been suggested as a predictor of benign nature in some studies.6,8 On this basis, we investigated the utility of MR fat-suppressed sequences to diagnose typical asymptomatic and aggressive vertebral haemangiomas.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The study was performed following the approval of the institution review board of our institution and was compliant with guidelines of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. A radiology information system query was performed on all MRI and CT examinations of the spine during the past 14 years to find patients with aggressive vertebral haemangiomas. Medical records were also reviewed for patient gender, age at the time of initial diagnosis and treatment history. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) fat-suppressed imaging [short tau inversion-recovery (STIR) or frequency-selective T2 fat saturation] performed as part of the routine MRI evaluation; (2) CT scan showing a typical imaging appearance of coarsened trabecula with “polka-dot” appearance; (3) presence of extraosseous soft-tissue component confirmed on both CT and MRI.

11 patients with typical non-aggressive vertebral haemangiomas were selected as control group with following criteria: (1) fat-suppressed imaging (STIR or frequency-selective T2 fat saturation) performed as part of the routine MRI evaluation; (2) MRI showing typical findings of haemangioma including T1 and T2 hyperintensity without any sign of aggressiveness such as vertebral expansion or perivertebral/epidural soft-tissue component; (3) CT scan showing a typical imaging appearance of coarsened trabecula with “polka-dot” appearance; (4) prior or follow-up CT or MRI that confirmed stability of the haemangioma; (5) absence of any symptom directly referable to the haemangioma. With regard to the underlying disease in control patients with asymptomatic typical haemangioma, three patients were imaged for the evaluation of degenerative disk disease, three had diskitis–osteomyelitis at a distant level, one patient was imaged for initial staging of lymphoma, one had prostate cancer, one had a distant meningioma, one had a remote vertebral body acute fracture and one patient was imaged owing to generalized weakness. Patients with history of radiotherapy, systemic chemotherapy or treatment with antiangiogenic agents and patients without fat-suppressed sequences on MRI were excluded from the study. Patients with history of surgery/biopsy or any intervention of the involved vertebra were also excluded.

CT and MRI imaging protocol

CT imaging was performed on multidetector (4–128) detector CT scanners (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Axial, sagittal and coronal CT slices had been reconstructed at 2- to 5-mm thickness. MR studies were performed with 1.5-T MR systems (Siemens Healthcare). MR sequence technique varied among patients but generally included sagittal T1 and T2, axial T1 and T2, and either sagittal STIR or frequency-selective fat saturation T2 weighted imaging.

Image analysis

All MR sequences and CT scans were used to define the location and extent of vertebral haemangioma. For quantitative analysis, a variable in size region of interest (ROI) based on haemangioma size was drawn around the entire circumference of the haemangioma on sagittal fat-suppressed sequences (STIR or T2 fat saturation) to measure the SI. The section in which the haemangioma was the largest was selected for this measurement. A second standard 25-mm2 ROI was also drawn on the brightest part of each haemangioma on the fat-suppressed sequences to measure the SI. Because of the potential variations of SI in different patients, the SI in a normal vertebral body (reference vertebral body) was also measured to serve as an internal control and for normalization of SI measurements. A 125-mm2 ROI was drawn on a normal vertebral body in the midline on the fat-suppressed sequences, within two levels above or below the haemangioma (Figure 1). Care was taken to avoid surrounding structures such as intervertebral disks, vertebral endplate degenerative signal changes and thecal sac/cerebrospinal fluid during ROI placements. Basivertebral venous plexus was also avoided during ROI placement in the reference normal vertebral bodies. Two neuroradiologists (SAN and SM) selected ROIs independently.

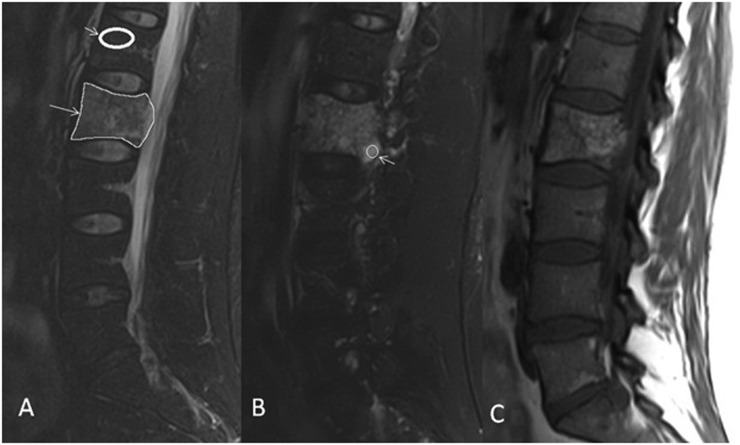

Figure 1.

Region of interest (ROI) placement in a 43-year-old patient with aggressive haemangioma of L2 vertebra (Patient 1). (a) Sagittal T2 fat saturation image shows ROI placement over the entire haemangioma (long arrow) and normal vertebral body (short arrow). (b) Sagittal T2 fat saturation image shows ROI placement over the brightest part of the lesion (arrow). (c) Sagittal T1 weighted image demonstrates extension of haemangioma beyond the posterior margin of the vertebral body.

Statistical analysis

Data were subsequently imported into the R statistical environment for visualization and analysis9 or quantitative measurements, interrater reliability was calculated with intraclass correlations. Group differences in SIs were assessed via the Mann–Whitney U test. In order to control for multiple testing, a Bonferroni-corrected α of <0.0125 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were then performed using the “pROC” package.10 In order to determine the optimum discriminatory threshold, Youden's J statistic was calculated, which maximizes distance on the ROC curve from the identity line.11 Based on this threshold, sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value and negative-predictive value were calculated for correct identification of aggressive haemangioma, hence aggressive haemangiomas that were correctly classified were considered true positive and typical haemangiomas that were correctly classified were considered true negative.

RESULTS

A total of 17 adult patients and 1 paediatric patient with an aggressive vertebral haemangioma were found. Nine patients were excluded owing to the lack of fat-suppressed sequences and one adult patient with diffuse benign hemangioendothelioma of the skeleton involving multiple ribs and vertebral bodies was excluded because of prior radiation treatment. A total of 8 patients (5 female and 3 male) with aggressive vertebral haemangioma and 11 patients (8 female and 3 male) with asymptomatic typical vertebral haemangioma were included in this study. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) age of patients with aggressive haemangioma was 46.6 ± 18.8 years (median 49 months, range 14–67 years). The mean ± SD age of patients with typical haemangioma was 61.7 ± 15.2 years (median 67 months, range 37–85 years).

In patients with aggressive haemangioma, six had sagittal STIR and two had sagittal T2 fat-saturation sequence. All of the control patients had a sagittal STIR sequence. The average time interval between MRI and CT imaging was 9.2 ± 18.2 months (median 3 months) in patients with aggressive haemangioma and 20.9 ± 27.4 months (median 5 months) in patients with typical haemangioma. The average follow-up imaging available in patients with typical haemangioma was 34.3 ± 37.2 months (median 24 months). In patients with aggressive haemangioma, four were thoracic and four were lumbar in location. In patients with typical haemangioma, six were thoracic and five were lumbar in location.

Four patients with aggressive haemangioma in the lumbar spine presented with radicular symptoms and one patient with thoracic spine haemangioma presented with myelopathic symptoms. Two patients with aggressive haemangioma of the thoracic spine presented with non-specific mid-back pain and one patient was asymptomatic, with the study that was performed to evaluate an incidentally found haemangioma on a neck MRI.

In patients with aggressive haemangioma, four were treated with ethanol ablation and one patient was treated with embolization, followed by laminectomy and resection of the epidural component. Three patients with aggressive haemangioma did not receive any treatment. None of the patients with typical haemangioma received any treatment or biopsy of the lesion and as mentioned in the methods section, all of them remained stable in size and imaging appearance.

With regard to T1 SI in patients with aggressive haemangioma compared with normal vertebral bodies, four patients demonstrated T1 hyperintensity both in the vertebral and extravertebral component of the haemangioma, two patients demonstrated T1 hypointensity both in the vertebral and extravertebral component of the haemangioma, and in two patients, the extravertebral component was isointense and vertebral component was hypointense compared with normal vertebral bodies.

Interrater reliability demonstrated excellent agreement between readers for all quantitative measures between (intraclass correlations of 0.99 for total mean SI, 0.99 for total maximum SI, 0.98 for brightest mean SI, 0.97 for brightest maximum SI). All standardized ratio measures were statistically different between groups; total normalized mean SI ratio (3.14 vs 1.48, p = 0.0002), total normalized maximum SI ratio (5.72 vs 2.55, p = 0.0003), brightest normalized mean SI ratio (4.28 vs 1.72, p < 0.0001) and brightest normalized maximum SI ratio (5.25 vs 2.45, p = 0.0003) (Figures 2 and 3).

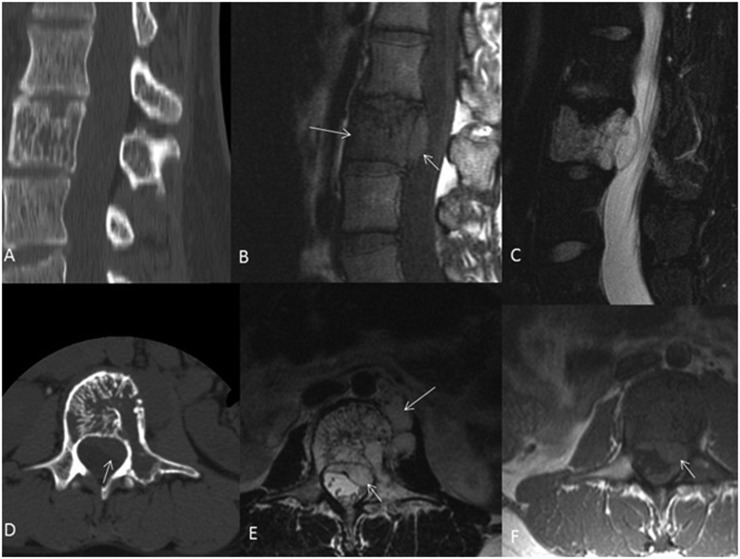

Figure 2.

A 27-year-old female with aggressive haemangioma of L3. Sagittal and axial CT scans (a and d) demonstrate L3 vertebral body lesion with involvement of the left pedicle and typical coarse bony trabeculae. Sagittal T1 weighted image (b) demonstrates that the vertebral component of the lesion is hypointense compared with marrow space other vertebral bodies and the epidural component is isointense. Sagittal T2 fat-saturated image (c) demonstrates marked hyperintensity of the haemangioma, both intra- and extraosseous portions, compared with the normal, adjacent vertebral bodies. Axial T2 and T1 weighted images (e and f, respectively) more clearly demonstrate the epidural and paravertebral components of this aggressive haemangioma.

Figure 3.

A 85-year-old patient with typical haemangioma of the T11 vertebral body. Sagittal T1 (a) and T2 weighted (b) images demonstrate T1 and T2 hyperintense lesion within the T11 vertebral body (arrows). Sagittal short tau inversion-recovery image (c) demonstrates only mild hyperintensity (arrow) compared with normal vertebral bodies. Sagittal CT reconstruction (d) demonstrates the typical coarsened vertical bony trabeculae (jail bars) consistent with a haemangioma (arrow).

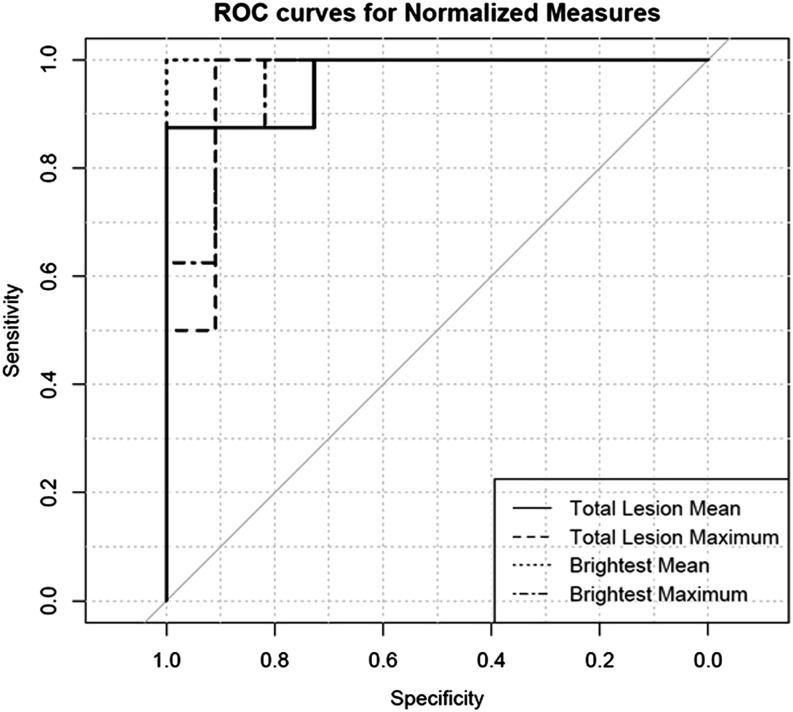

Owing to excellent agreement in quantitative measurements between the readers, the ROIs from Reader 1 was used to do group and ROC analysis. The parameter with highest accuracy in distinguishing aggressive haemangiomas from typical vertebral body haemangiomas, as determined by the total area under the ROC curve was the brightest normalized mean SI ratio [area under the curve (AUC) = 1], followed by total normalized mean SI ratio (AUC = 0.97), total normalized maximum SI ratio (AUC = 0.95) and brightest normalized maximum SI ratio (AUC = 0.95) (Figure 4). Threshold analysis of the ROC data revealed that using a threshold value of 2.92, the brightest normalized mean SI ratio value was able to diagnose aggressive vertebral haemangioma with 100% sensitivity, 100% specificity, 100% positive-predictive value and 100% negative-predictive value in our sample (Table 1 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for different metrics. Brightest normalized mean signal intensity ratio has the highest accuracy with 100% sensitivity and specificity for differentiation of aggressive from typical asymptomatic vertebral body haemangiomas.

Table 1.

Different threshold values for differentiation of aggressive and typical asymptomatic vertebral haemangiomas

| Different parameters | Total lesion normalized mean SI ratio | Total lesion normalized maximum SI ratio | Brightest normalized mean ROI SI ratio | Brightest normalized maximum ROI SI ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.95 |

| Thresholda | 2.41 | 3.78 | 2.92 | 3.57 |

| Sensitivity | 88% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Specificity | 100% | 91% | 100% | 82% |

| PPV | 100% | 89% | 100% | 80% |

| NPV | 92% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

AUC, area under the curve; NPV, negative-predictive value; ROI, region of interest; PPV, positive-predictive value; SI, signal intensity.

Optimum thresholds of receiver operating characteristic curves were determined via Youden’s J.

Figure 5.

Comparison of brightest normalized mean region of interest signal intensity ratio with overlayed threshold (2.92) demonstrates perfect accuracy for the differentiation of aggressive and asymptomatic vertebral haemangiomas. NPV, negative-predictive value PPV, positive-predictive value.

Comparison of the ROC curves demonstrated that although the brightest normalized mean SI ratio provided the highest accuracy compared with other metrics, the difference was not statistically significant (p-values ranging from 0.23 to 1 for both readers). There was also no statistically significant difference in ROC curves between the readers (p-values ranging from 0.29 to 1).

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrated that quantitative SI ratio evaluation of fat-suppressed sequences is significantly different in typical asymptomatic haemangioma from aggressive haemangioma. Unlike asymptomatic vertebral haemangiomas that are hyperintense on both T1 and T2 weighted sequences, aggressive vertebral haemangiomas are known to have low to isointense signal on T1 weighted images and high signal on T2 weighted images.4,7 Laredo et al8 investigated the appearance of the stroma between the osseous trabeculae on vertebral haemangiomas and demonstrated absence of fat attenuation on CT in aggressive haemangiomas, in comparison to asymptomatic haemangiomas. In their study, aggressive haemangiomas showed numerous packed, thin-walled vascular cavities with absence of fatty replacement on histopathological evaluation.8 Ross et al12 and Pastushyn et al6 also demonstrated that the paravertebral extraosseous component of aggressive haemangiomas is hypointense on T1 weighted images. In the study by Ross et al,12 histopathological evaluation of the extraosseous portion of the tumour showed a preponderance of angiomatous tumour vessels and fibrous tissue, with little adipose tissue. Although a few of the previous studies showed hyperintensity on STIR sequence in their published figures of aggressive haemangioma,5,13 we are not aware of any study which was dedicated to qualitative or quantitative comparison of fat-suppressed sequences between different subtypes of haemangioma. Our result with regard to absence of T1 hyperintensity in aggressive haemangioma is somewhat concordant with prior studies,6,8,12 as we also observed hypoisointense components in aggressive haemangiomas in four patients; however, in four patients, the aggressive haemangioma was T1 hyperintense. Therefore, based on our study, T1 signal is not a reliable marker for aggressive haemangioma. We did not have histopathological correlation of imaging findings in our study since most of the cases were treated by ethanol injection; however, we believe that high proportion of vascular stroma and oedema along with relative paucity of adipose tissue accounts for the hyperintensity on STIR and chemical fat-saturated T2 weighted sequences.

Although vertebral haemangiomas are usually asymptomatic, they can rarely (<1%)4 cause neurologic symptoms, secondary to spinal cord/nerve root compression, which can result from ballooning expansion of vertebral body/posterior elements or from direct extension of the haemangioma through the cortex into the epidural space or neural foramen.14 In addition, there have been reports of an entity called “symptomatic vertebral haemangioma” which is seen in patients who are being evaluated for back pain of indeterminate origin.8 These haemangiomas could be incidental in patients with unrelated back pain but some may be the cause of back pain and there is at least one report in the literature that demonstrated substantial change in the radiologic appearance of a vertebral haemangioma with cortical expansion and extension to the neural arch over the course of 4 years in a patient with back pain.8 Most of our patients with aggressive haemangiomas were referred from outside institutions to receive treatment and we did not have long-term prior imaging.

There are several traditional treatment methods in patients with aggressive haemangiomas, which include decompressive surgery or radiation therapy. More recently, direct puncture and perfusion of the haemangioma with absolute ethanol has been successfully used.5,15,16

Our study has some limitations including small sample size which results partly from rarity of aggressive haemangioma and our strict inclusion criteria for aggressive haemangiomas and typical asymptomatic haemangiomas and lack of fat-suppressed sequences in some patients in this retrospective study. In addition, we did not have long-term follow-up imaging in treatment-naïve patients with aggressive haemangiomas as these patients were predominantly referred to our institution for ethanol injection. Finally, this study is limited by lack of histopathology which is secondary to the non-surgical treatment modality in most of the treated patients. The next step would be to investigate the utility of fat-suppressed sequences to predict expansion of a vertebral haemangioma and to identify potentially aggressive haemangiomas in early stages before they become symptomatic.

CONCLUSION

In addition to the conventional imaging features such as vertebral expansion and presence of extravertebral component, quantitative evaluation of fat-suppression sequences is also another imaging feature that can differentiate aggressive haemangioma and typical asymptomatic haemangioma. The utility of this finding in identifying potentially aggressive haemangiomas in early stages should be further evaluated in larger prospective studies.

Contributor Information

Seyed Ali Nabavizadeh, Email: SeyedAli.Nabavizadeh@uphs.upenn.edu.

Alexander Mamourian, Email: alexander.mamourian@uphs.upenn.edu.

James E Schmitt, Email: James.Schmitt@uphs.upenn.edu.

Francis Cloran, Email: cloranf@gmail.com.

Arastoo Vossough, Email: Arastoo.Vossough-Modarress@uphs.upenn.edu.

Bryan Pukenas, Email: Bryan.Pukenas@uphs.upenn.edu.

Laurie A Loevner, Email: Laurie.Loevner@uphs.upenn.edu.

Suyash Mohan, Email: Suyash.Mohan@uphs.upenn.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huvos AG. Hemangioma, lymphangioma, angiomatosis, lymphangiomatosis, glomus tumor. In: Huvos AG, ed. Bone tumors: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1991. 553–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphey MD, Fairbairn KJ, Parman LM, Baxter KG, Parsa MB, Smith WS. From the archives of the AFIP. Musculoskeletal angiomatous lesions: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 1995; 15: 893–917. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.4.7569134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodallec MH, Feydy A, Larousserie F, Anract P, Campagna R, Babinet A, et al. Diagnostic imaging of solitary tumors of the spine: what to do and say. Radiographics 2008; 28: 1019–41. doi: 10.1148/rg.284075156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siemund R, Thurnher M, Sundgren PC. How to image patients with spine pain. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 757–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acosta FL, Jr, Sanai N, Chi JH, Dowd CF, Chin C, Tihan T, et al. Comprehensive management of symptomatic and aggressive vertebral hemangiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2008; 19: 17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastushyn AI, Slin'ko EI, Mirzoyeva GM. Vertebral hemangiomas: diagnosis, management, natural history and clinicopathological correlates in 86 patients. Surg Neurol 1998; 50: 535–47. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(98)00007-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaudino S, Martucci M, Colantonio R, Lozupone E, Visconti E, Leone A, et al. A systematic approach to vertebral hemangioma. Skeletal Radiol 2015; 44: 25–36. doi: 10.1007/s00256-014-2035-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laredo JD, Assouline E, Gelbert F, Wybier M, Merland JJ, Tubiana JM. Vertebral hemangiomas: fat content as a sign of aggressiveness. Radiology 1990: 177: 467–72. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.2.2217787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Core Team; 2014. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12: 77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950; 3: 32–5. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Modic MT, Carter JR, Mapstone T, Dengel FH. Vertebral hemangiomas: MR imaging. Radiology 1987: 165: 165–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.1.3628764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang L, Liu XG, Yuan HS, Yang SM, Li J, Wei F, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of vertebral hemangiomas with neurologic deficit: a report of 29 cases and literature review. Spine J 2014; 14: 944–54. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marymont JV, Shapiro WM. Vertebral hemangioma associated with spinal cord compression. South Med J 1988; 81: 1586–7. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198812000-00031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox MW, Onofrio BM. The natural history and management of symptomatic and asymptomatic vertebral hemangiomas. J Neurosurg 1993; 78: 36–45. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.1.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heiss JD, Doppman JL, Oldfield EH. Brief report: relief of spinal cord compression from vertebral hemangioma by intralesional injection of absolute ethanol. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 508–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]