Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate daily cholesterol intake across demographic factors and its food sources in elderly Chinese.

Design

A longitudinal study was conducted using demographic and dietary data for elders aged 60 and above from eight waves (1991–2011) of the China Health and Nutrition Survey.

Setting

The data were derived from urban and rural communities of nine provinces (autonomous regions) in China.

Participants

There were 16 274 participants (7657 male and 8617 female) in this study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was daily cholesterol intake, which was calculated by using the Chinese Food Composition Table, based on dietary data.

Results

Daily consumption of cholesterol in the elderly significantly increased by 34% from 1991 to 2011 (p<0.0001) and reached 253.9 mg on average in 2011. Secular trends in the proportion of subjects with an intake of >300 mg/day increased significantly during 1991–2011 (p<0.0001). The major food sources of cholesterol by ranked order were eggs, pork, and fish and shellfish in 1991 and 2011, while organ meats which ranked fourth in the contribution to total intake in 1991 was replaced by poultry in 2011. Moreover, younger elders, male elders and elders from a high-income family or a highly urbanised community had higher cholesterol intakes and larger proportions of subjects with excessive cholesterol consumption in each survey year.

Conclusions

The large growth in daily cholesterol intake may pose major challenges for the health of elders in China. Reduced exposure to food enriched in cholesterol is required for elderly Chinese.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, NUTRITION & DIETETICS, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study observed that the daily cholesterol intake in Chinese elders increased from 1991 to 2011, as did the proportion of participants with a cholesterol intake of >300 mg/day. The older population in China needs to pay attention to their intake from the food groups, eggs, pork, fish and shellfish.

The primary limitation of this study is that the accuracy of the estimates of daily cholesterol intake was limited by the accuracy of recall of the survey participants, based on a dietary survey.

Food grouping can have a major influence on the ranked order of dietary sources, as the number of food groupings or ingredients in food groups may differ from previous studies conducted in various countries.

Introduction

The dietary habits of the general population are undergoing substantial changes associated with socioeconomic transitions occurring worldwide, including developing countries.1–3 Changes in dietary patterns may have an impact on the trends of dietary-related risk factors for chronic diseases. Dietary cholesterol has been reported to be linked to the prevalence of age-related hearing loss,4 the progression of liver disease,5 and, especially, higher risk of stroke6 and cardiovascular disease.7 International guidelines for cholesterol intake provide specific numerical recommendations or recommend changing the pattern of fat consumption.8 9

Major alterations in population structure are occurring in China along with a rapidly growing economy. According to recent estimates by the United Nations, elderly people aged >60 made up 14.9% of the Chinese population in 2015, and this proportion is projected to increase dramatically to 32.8% in 2050.10 China is the most populous country in the world with a total population of >1.3 billion, and it has the largest aging population.11 The health and nutrition of the elderly are increasingly arousing concern nationwide. Elderly people are at high risk of chronic diseases. Dietary modification of lipid intake is the first-line therapy for those at risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease, with a major focus of current guidelines being to reduce intake of saturated fatty acids.12 Although there are inconsistencies among studies on the relationship between cholesterol intake and cardiovascular outcomes, a systematic review reports that dietary cholesterol significantly increases serum total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.13 As such, it is essential to evaluate dietary cholesterol intake in the elderly. Most previous studies conducted a short-term assessment of daily cholesterol intake in elderly people.14–16 Mean cholesterol consumption was low and did not exceed the recommended 300 mg daily intake in free-living elders from rural environments, especially in individuals at risk of malnutrition,14 whereas 38.3% of the elderly living in long-term care facilities had a higher cholesterol intake than the recommended level.15 These reports also indicated that the dietary cholesterol intake of the elderly is probably conditioned by the place of residence, economic status, education level, type of family and dietary pattern. However, a short-term assessment hardly shows any changes in daily cholesterol intake over time, and the food origins of dietary cholesterol were seldom investigated in previous studies,14–16 which limited interventions for higher cholesterol intake in the elderly. A few studies longitudinally reported that the mean daily cholesterol intake and the proportion of people with greater intake than the recommended level increased in both Taiwanese and Chinese adults,17 18 but no similar studies in the elderly are available, especially in developing countries. A secular evaluation of daily cholesterol intake and its food sources in the elderly is therefore required.

Using the data of the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), we aimed to assess the changes in dietary cholesterol intake and its food sources in elderly Chinese aged 60 years and older from 1991 to 2011, and to evaluate the differences in dietary cholesterol intake by demographic factors.

Methods

Study population

We used data from the CHNS, which is an ongoing series of longitudinal household surveys with the goal of examining how the social and economic changes in China affect various nutrition- and health-related outcomes. The CHNS was conducted in nine rounds between 1989 and 2011 across nine provinces (autonomous regions). Multistage, random cluster sampling was used to select the survey sample in each province to ensure that the CHNS provided a representation of urban and rural areas. The survey design and methods have been described in detail elsewhere.19

Our analysis used eight waves of survey data between 1991 and 2011. The CHNS average response rates between 1991 and 2011 at the individual and household levels were reported to be about 85% and 90%, respectively, relative to the previous round of data.19 20 From all the participants aged 60 and above, who had full socioeconomic status and demographic data and 3-day 24-hour dietary recall data, we excluded those with implausible energy intakes (<800 kcal/day or >6000 kcal/day for men and <600 kcal/day or >4000 kcal/day for women). The analysis therefore consisted of 1319, 1400, 1654, 1937, 2140, 2331, 2613 and 2880 participants in 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009 and 2011 survey years, respectively. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Dietary data

Household food consumption data and individual dietary recall data were collected over three consecutive days, as described in detail elsewhere.19 21 Briefly, household food consumption, including all foods and condiments, was determined using a weighing method. Individual dietary intake data were collected by asking each household member to report all food consumed (types, amounts, type of meal, and place of consumption) at home and away from home on a 3-day 24-hour recall basis.

Assessment of dietary cholesterol intake

The Chinese Food Composition Table21 was used to calculate individual daily intake of cholesterol for each food item in the dietary data.

Evaluation of household income

Per capita annual household income (RMB/persons×year) was obtained by asking the head of the household and categorised into tertiles (low, medium and high).19

Evaluation of urbanicity

The standardised, validated urbanisation measure captures changes in the following 12 dimensions at the community level: population density, economic activity, traditional markets, modern markets, transportation infrastructure, sanitation, communications, housing, education, diversity, health infrastructure and social services.22 Each is based on numerous measures applicable to each dimension. The urbanicity index (score) was categorised into tertiles (low, medium and high).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean (SE) or median for continuous variables, and percentage of the total for categorical variables. Data were analysed using both descriptive and analytical statistics. The study sample was subdivided according to different demographic factors. Adjusted means and SEs were used to describe the distribution of continuous variables after adjustment for complex sampling and the covariates age, sex, household income level and urbanisation. Analysis of variance was used to compare the differences in daily cholesterol intake over eight rounds of the CHNS, and the Cochran-Armitage trend test was used to test the trend in the proportions of subjects with a daily cholesterol intake of >300 mg during 1991–2011. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.1 software. p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the subjects

More than half of the subjects were 60–70 years old, and a small proportion were 80 years old or above in each survey (table 1). The proportion of female subjects was slightly higher than male subjects over the whole time. The medians across tertiles of per capita annual income and urbanisation level of targeted communities tended to increase from 1991 to 2011.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the subjects by survey year

| Survey year |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 1991 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 |

| No of subjects | 1319 | 1400 | 1654 | 1937 | 2140 | 2331 | 2613 | 2880 |

| Age group (years), % | ||||||||

| 60–70 | 64.7 | 64.6 | 62.5 | 61.6 | 58.1 | 57.4 | 57.1 | 57.0 |

| 70–80 | 28.9 | 28.8 | 29.5 | 30.2 | 33.4 | 33.7 | 32.9 | 32.3 |

| 80+ | 6.4 | 6.6 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 10.7 |

| Gender, % | ||||||||

| Male | 48.2 | 47.4 | 46.1 | 46.1 | 47.4 | 47.0 | 47.5 | 46.9 |

| Female | 51.8 | 52.6 | 53.9 | 53.9 | 52.6 | 53.0 | 52.5 | 53.1 |

| Income, RMB/person×year* | ||||||||

| Low | 1094.8 | 1128.6 | 1199.6 | 1248.3 | 1708.3 | 1782.2 | 2928.8 | 3014.8 |

| Medium | 2594.5 | 2619.2 | 2902.6 | 4016.6 | 5131.1 | 5226.2 | 8608.9 | 10209.3 |

| High | 4634.7 | 5524.1 | 5870.9 | 8699.1 | 12346.5 | 13892.6 | 19713.8 | 23976.2 |

| Urbanicity index, score† | ||||||||

| Low | 30.3 | 30.7 | 33.6 | 40.9 | 41.4 | 41.7 | 47.2 | 49.8 |

| Medium | 52.8 | 54.8 | 61.6 | 67.5 | 70.5 | 70.7 | 72.8 | 76.0 |

| High | 66.1 | 68.7 | 76.0 | 80.5 | 86.8 | 89.3 | 90.6 | 92.6 |

*Per capita annual household income (RMB/person×year), inflated to 2011. Values presented as median of each tertile.

†Measured at the community level on a 12-component continuous scale ranging from 0 to 120. Values presented as median of each tertile.

Changes in daily cholesterol intake across sociodemographic factors between 1991 and 2011

Daily cholesterol intake of all subjects was significantly different over the eight survey years (table 2, p<0.0001), and mean daily cholesterol intake was 189.8 and 253.9 mg in 1991 and 2011, respectively, increasing by 34% during 1991–2011. The increase of 99.4 mg in daily cholesterol intake from 1991 to 2011 in subjects aged 80 years and older was the most substantial of the three age groups, accounting for 68% of the level in 1991. The other two age groups had similar changes from 1991 to 2011. The daily cholesterol intake in women increased from 173.4 mg in 1991 to 241.2 mg in 2011, an increase of 39%, which is larger than the changes in men. Subjects with low household income showed a significant increase of 56% in daily cholesterol intake from 1991 to 2011, relative to subjects from medium- and high-income families. Daily cholesterol intake in subjects from less urbanised (rural) communities increased by 77.4 mg during 1991–2011 (72% of the baseline level), while the increment of 15% in daily cholesterol intake in subjects from highly urbanised regions was relatively small. As a whole, daily consumption of dietary cholesterol displayed a significant difference in subjects from each subgroup between 1991 and 2011 (all p<0.0001). In addition, younger elderly, male elderly, those from a high-income family and those from a highly urbanised community daily consumed a higher level of cholesterol in each survey year.

Table 2.

Daily cholesterol intake across sociodemographic factors in elderly Chinese, 1991–2011 (mg/day)

| 1991 |

1993 |

1997 |

2000 |

2004 |

2006 |

2009 |

2011 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | p Value* | |

| All | 189.8 | 6.5 | 194.6 | 6.4 | 223.2 | 3.9 | 226.7 | 5.7 | 242.7 | 4.2 | 244.4 | 5.5 | 252.5 | 5.5 | 253.9 | 4.8 | <0.0001 |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||||||||

| 60–70 | 195.4 | 8.3 | 200.7 | 7.9 | 230.3 | 7.2 | 233.3 | 5.3 | 246.8 | 5.8 | 250.8 | 6.9 | 256.1 | 7.2 | 257.7 | 6.4 | <0.0001 |

| 70–80 | 186.9 | 12.2 | 189.5 | 11.9 | 217.4 | 11.4 | 219.5 | 6.5 | 238.7 | 6.9 | 240.5 | 10.4 | 248.7 | 9.7 | 250.1 | 8.1 | <0.0001 |

| 80+ | 145.8 | 19.2 | 157.1 | 20.7 | 189.1 | 15.6 | 203.6 | 11.9 | 230.4 | 19.1 | 217.9 | 13.5 | 244.4 | 15.5 | 245.2 | 17.7 | <0.0001 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 207.3 | 9.9 | 219.0 | 9.9 | 241.9 | 6.0 | 242.6 | 9.2 | 258.7 | 6.7 | 259.5 | 8.5 | 265.7 | 8.3 | 268.2 | 7.1 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 173.4 | 8.6 | 172.7 | 8.1 | 207.2 | 5.1 | 213.1 | 7.0 | 228.3 | 5.2 | 231.0 | 7.2 | 240.5 | 7.3 | 241.2 | 6.4 | <0.0001 |

| Income level | |||||||||||||||||

| Low | 140.0 | 9.9 | 143.3 | 10.0 | 190.9 | 8.3 | 193.5 | 6.3 | 209.1 | 9.6 | 211.9 | 10.4 | 216.3 | 8.6 | 218.0 | 7.6 | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 198.5 | 12.4 | 205.5 | 9.4 | 222.0 | 9.4 | 225.8 | 6.2 | 242.4 | 9.1 | 242.8 | 7.1 | 247.1 | 7.5 | 248.6 | 10.0 | <0.0001 |

| High | 229.7 | 11.3 | 234.7 | 13.0 | 255.3 | 10.2 | 259.4 | 8.0 | 275.4 | 7.5 | 280.3 | 10.3 | 293.5 | 8.5 | 295.1 | 9.5 | <0.0001 |

| Urbanicity index | |||||||||||||||||

| Low | 107.1 | 8.0 | 113.9 | 9.3 | 144.8 | 7.6 | 153.1 | 7.5 | 166.1 | 8.0 | 169.4 | 6.1 | 182.6 | 7.2 | 184.5 | 8.0 | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 183.2 | 10.9 | 189.3 | 10.9 | 240.5 | 6.1 | 244.3 | 9.5 | 253.4 | 7.6 | 254.3 | 9.1 | 255.8 | 8.5 | 256.4 | 9.7 | <0.0001 |

| High | 277.6 | 8.3 | 280.4 | 12.9 | 282.6 | 6.6 | 283.1 | 11.8 | 308.2 | 10.9 | 309.5 | 7.7 | 318.2 | 10.1 | 320.6 | 10.1 | <0.0001 |

*Analysis of variance; results were considered to be significant when p<0.05.

Change in food sources of daily cholesterol intake in 1991 and 2011

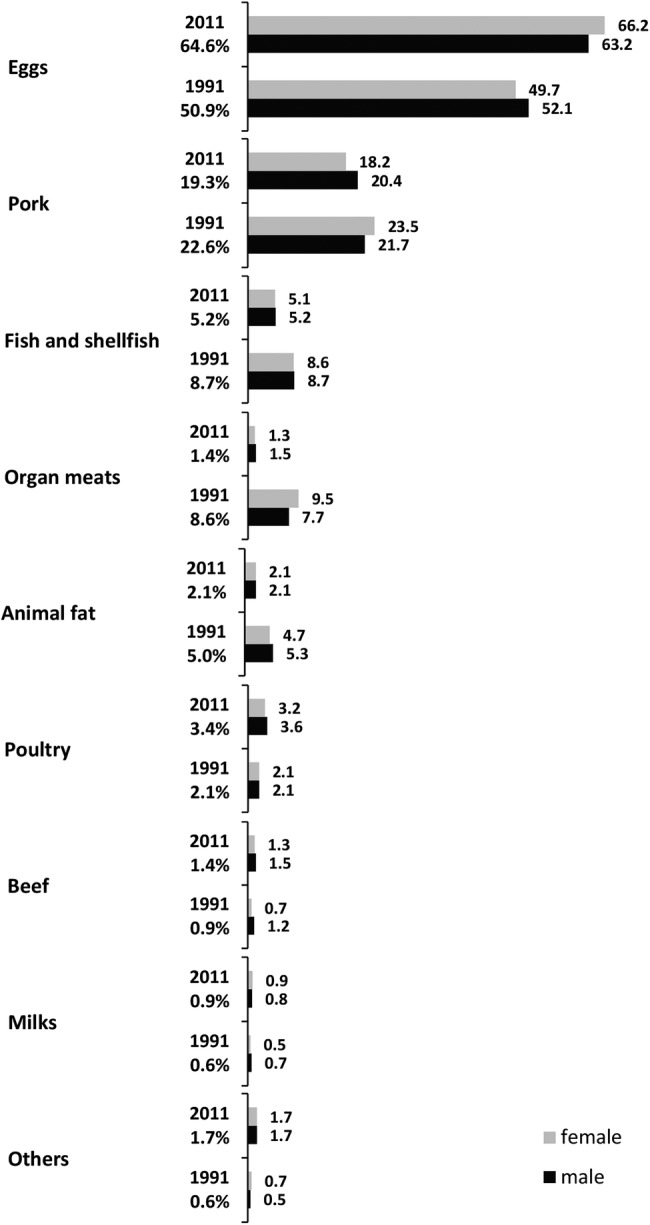

The top three food sources were eggs, pork, and fish and shellfish in elderly Chinese, and the contribution to the total daily cholesterol intake was 50.9%, 22.6% and 8.7% in 1991 and 64.6%, 19.3% and 5.2% in 2011, respectively (figure 1). Daily cholesterol intake from organ meats (offal) (8.6%) ranked fourth in 1991, while that from poultry (3.4%) ranked fourth in 2011, followed by animal fat, accounting for 5.0% and 2.1% of total daily cholesterol intake in 1991 and 2011, respectively. Only 1.4% of dietary cholesterol originated from organ meats in 2011, unlike that in 1991. Cholesterol intake from beef and milk was negligible in both 1991 and 2011. In addition, men and women had similar patterns of food sources of daily cholesterol intake in 1991 and 2011, except for a slight difference in fish and shellfish and organ meats in 1991.

Figure 1.

Contribution of food items to total daily cholesterol intake in elderly Chinese in 1991 and 2011. Values are expressed as percentages. Grey and black bars denote the proportions in women and men, respectively.

Trends in proportions of subjects with excessive daily cholesterol intake from 1991 to 2011

Trends in proportions of subjects with a cholesterol intake of >300 mg/day from 1991 to 2011 increased significantly in all subjects as well as in subjects from each subgroup (table 3, all p<0.0001). The proportion of elderly who consumed excessive cholesterol increased from 21.4% in 1991 to 33.2% in 2011 in the present study. The increments in the proportions of subjects with higher daily cholesterol intake than the recommended level from 1991 to 2011 were most significant in subjects 80 years and older, women, those from a low-income family, and those from low- and medium-urbanised communities, increasing by 84%, 67%, 85%, 91% and 85%, respectively. The proportions of subjects 60–70 years old, men, those from a high-income family and those from a highly urbanised community tended to be higher in each survey year.

Table 3.

Proportions of subjects with more than 300 mg/day cholesterol intake across socio-demographic factors, 1991–2011 (%)

| 1991 |

1993 |

1997 |

2000 |

2004 |

2006 |

2009 |

2011 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | p Value* | |

| All | 21.4 | 1.1 | 21.8 | 1.1 | 27.5 | 0.8 | 28.2 | 1.1 | 30.0 | 1.0 | 30.1 | 0.9 | 32.1 | 1.0 | 33.2 | 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||||||||

| 60–70 | 22.2 | 1.4 | 22.4 | 1.4 | 29.1 | 1.1 | 29.9 | 1.4 | 31.6 | 1.4 | 31.5 | 1.2 | 33.2 | 1.3 | 34.3 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| 70–80 | 20.8 | 2.0 | 21.3 | 2.1 | 25.7 | 1.5 | 26.7 | 2.0 | 28.9 | 1.9 | 29.0 | 1.6 | 31.7 | 1.7 | 32.5 | 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| 80+ | 16.0 | 3.4 | 17.6 | 4.1 | 19.2 | 2.6 | 20.6 | 3.4 | 23.4 | 3.7 | 25.2 | 2.8 | 26.1 | 3.2 | 29.5 | 3.6 | <0.0001 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 24.3 | 1.7 | 24.8 | 1.7 | 30.0 | 1.2 | 30.4 | 1.7 | 32.8 | 1.3 | 33.0 | 1.6 | 33.4 | 1.5 | 35.5 | 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 18.7 | 1.3 | 18.9 | 1.5 | 25.4 | 1.1 | 26.3 | 1.5 | 27.4 | 1.2 | 27.5 | 1.4 | 30.8 | 1.4 | 31.2 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Income level | |||||||||||||||||

| Low | 15.1 | 1.7 | 15.4 | 1.7 | 21.7 | 1.3 | 22.0 | 1.6 | 24.2 | 1.5 | 24.6 | 1.7 | 26.8 | 1.5 | 27.9 | 1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 21.3 | 2.0 | 22.1 | 2.0 | 28.5 | 1.5 | 30.1 | 1.7 | 31.4 | 1.7 | 31.7 | 1.8 | 31.8 | 1.6 | 32.3 | 1.9 | <0.0001 |

| High | 27.9 | 2.2 | 28.1 | 1.9 | 31.4 | 1.6 | 32.5 | 1.9 | 34.4 | 1.8 | 34.0 | 1.9 | 37.7 | 1.6 | 39.4 | 2.0 | <0.0001 |

| Urbanicity index | |||||||||||||||||

| Low | 11.6 | 1.5 | 12.1 | 1.4 | 15.9 | 1.4 | 17.1 | 1.5 | 18.9 | 1.4 | 19.6 | 1.2 | 21.2 | 1.4 | 22.1 | 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 18.3 | 1.8 | 18.8 | 1.9 | 28.5 | 2.0 | 29.9 | 1.5 | 31.2 | 1.4 | 31.8 | 1.8 | 32.6 | 1.7 | 33.9 | 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| High | 34.3 | 2.2 | 34.5 | 2.3 | 38.4 | 2.1 | 37.6 | 2.0 | 39.7 | 1.9 | 38.9 | 1.8 | 42.4 | 1.7 | 43.5 | 1.8 | <0.0001 |

*Analysis by Cochran-Armitage trend test; results were considered to be significant when p<0.05.

Discussion

The present study used representative data of eight waves derived from the CHNS, and found that daily consumption of dietary cholesterol in elderly Chinese aged 60 years and older gradually increased from 1991 to 2011 and reached 253.9 mg on average in 2011, which is higher than the mean dietary cholesterol consumption (228 mg/day) in the global adult population in 2010.23 Moreover, the daily intake as early as the survey of 2004 had been more than the global mean in 2010,23 suggesting an unexpected higher intake of cholesterol even in Chinese elders. Furthermore, secular trends in the proportion of elderly Chinese with a cholesterol intake of >300 mg/day increased significantly over the past two decades. The major food sources of dietary cholesterol by ranked order were eggs, pork, and fish and shellfish in 1991 and 2011. This study also indicates that younger elders, male elders, and elders from a high-income family or a highly urbanised community in China had higher daily cholesterol intakes and larger proportions of subjects with excessive cholesterol consumption in each survey year. Our group previously evaluated the trends in dietary cholesterol intake and its food sources in Chinese adults younger than 60 years.24 Like that study, the present study shows that Chinese elders had comparable and increasing cholesterol intake over time, and the same top three food sources. On the basis of these findings, it is certain that the Chinese population is experiencing a large growth in daily cholesterol intake along with the rapid socioeconomic transitions, and the consequent potential challenges for the health of the population need to be met.

On the basis of the daily consumption of dietary cholesterol found in the present study, men appeared to have a higher intake than women in each survey year. Likewise, a 24-hour dietary recall survey in elderly Taiwanese aged 65 and over carried out from 1999 to 200016 found that cholesterol intake in men (251 mg/day) was higher than in women (172 mg/day). Similar investigations in participants aged 35–74 years across 10 western European countries between 1995 and 2000 also found that the average cholesterol intake varied from 140 to 384 mg/day in women and from 215 to 583 mg/day in men.25 These gender differences may be attributable to dietary intake amount, dietary habits and preference. Moreover, we found that the intake in elderly Chinese was higher than the lowest cholesterol intake observed in the UK (mean intake of 215 mg in men and 140 mg in women) in the same period.25 The present study further shows that the trends in proportions of subjects with a cholesterol intake of more than the recommended 300 mg/day increased significantly from 1991 to 2011 in total participants, as well as in each subgroup. Relative to the reported 38.3% of elderly subjects (65 years and over) who did not meet the recommended cholesterol intake between 1997 and 1999 in Canada,15 the proportions between 1997 and 2000 in our study were much lower, which may be linked to socioeconomic status, food supply and choice. However, a secular trend toward a higher proportion of elderly Chinese with excessive cholesterol intake during the past two decades raises serious concerns over their cholesterol consumption, and indicates that monitoring and regulation of dietary intake in Chinese, especially the elderly, are required.

Healthy aging is one of the most serious challenges associated with population aging worldwide. It has been shown that an incorrect diet facilitates the development of many non-contagious and chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.14 As we know, lipid intake, including cholesterol, has a major impact on modulating the risk and severity of a number of the aforementioned chronic diseases.26 Here, the top three food sources of dietary cholesterol were eggs, pork, and fish and shellfish, which cumulatively contributed 82.2% and 89.1% to total intake in 1991 and 2011, respectively. Although the available literature data are limited, the primary dietary sources of cholesterol in Taiwanese elders were eggs/egg products (30.9%), pork/pork products (24.7%), and saltwater fish (9.8%), together accounting for 65.4% of total intake.16 Thus, the main food sources of dietary cholesterol in Chinese elders agree with those in Taiwanese elders. On the other hand, the significant differences in the contribution rates of the three main foods to total cholesterol intake between Chinese and Taiwanese elders indicates the food choices of Chinese elders: greater consumption of eggs and less intake of pork and fish. Compared with the main food sources of cholesterol in older people from European countries—meat, eggs, dairy products, fish and cakes in that order25—it is clear that meat and eggs had the opposite ranking in China and European countries; dairy products and cakes provided negligible cholesterol for Chinese elders, and offal was a unique source in China, especially playing a major role in cholesterol intake in 1991. As we know, egg, poultry, lean meats and fish are sources of good protein which is essential for healthy aging. Therefore, although the top three food sources of cholesterol covered egg, pork and fish in elderly Chinese, here we highlight the importance of modifying dietary habits by developing a balanced diet in order to prevent frailty and sarcopenia in the aging population.

Socioeconomic status can obviously influence dietary habits,27 although this may not necessarily be reflected in differences in lipid intake.28 In our study, household income level and urbanicity index as a proxy of socioeconomic status partially explains the variation in cholesterol intake in elderly Chinese. In particular, the consumption of cholesterol in subjects from a highly urbanised community was close to or above the recommended intake from 1991 to 2011. And the socioeconomic transitions from 1991 to 2011 had an overwhelming impact on cholesterol intake for elders from a low-income family or a less urbanised community. In addition, we observed that younger elders (60–70 years) tended to consume more cholesterol, resulting in a higher proportion with intake in excess of the recommendation, in comparison with older elders (70–80 years or 80 years and more). One of the main reasons is the difference in amount of dietary intake, which is always reduced in elderly people and worsens with aging.15 This may have multiple causes. First, there is a reduction in energy needs because the basal metabolic rate declines by 3–4% or 100 calories per decade. Loss of appetite, decrease in taste, smell and thirst sensations, digestive problems, lactose intolerance, and poor oral health are other contributing factors.15 29 30

The present study has several limitations. As with all studies based on dietary survey, the accuracy of the intake estimates was limited by the accuracy of recall of the survey participants and the specificity with which the reported foods were mapped in the dietary recall records. In addition, food grouping can have a major influence on the ranked order of dietary sources; thus, caution is advised when comparing these data with previous reports.16 25

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study provides representative data on daily cholesterol intake and its food sources in elderly Chinese during 1991–2011. Daily consumption of cholesterol gradually increased from 1991 to 2011, which was mainly from eggs, pork, and fish and shellfish. Moreover, secular trends in the proportion of subjects with cholesterol intake above the recommended level have been towards higher values for two decades. These situations are more significant in younger elders, male elders, and elders from a high-income family or a highly urbanised community in each survey year. As cholesterol intake is reported to be linked to serum lipid levels being risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in several studies, the present study indicates that we need to try to control cholesterol intake and develop healthy eating habits in the older population, especially those with chronic diseases or hyperlipidaemia.

Acknowledgments

The present study uses data from the CHNS. We thank all participants and staff involved in the surveys.

Footnotes

Contributors: XJ conceptualised and drafted the manuscript; CS participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis, as well as interpreting the results; ZW, HW, HJ and BZ were involved in critically reviewing a draft of the manuscript and contributed to data collection and data cleaning. BZ further supervised this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute for Nutrition and Health, China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Carolina Population Center (5 R24 HD050924); the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the NIH (R01-HD30880, DK056350, R24 HD050924, R01-HD38700); Danone Institute China Diet Nutrition Research and Communication Grant (DIC2013-02) in 2013; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81172666); and Youth Foundation of Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (No 2013B103). All funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Oza-Frank R, Cheng YJ, Narayan KM et al. Trends in nutrient intake among adults with diabetes in the United States: 1988–2004. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:1173–8. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramazauskiene V, Petkeviciene J, Klumbiene J et al. Diet and serum lipids: changes over socio-economic transition period in Lithuanian rural population. BMC Public Health 2011;11:447 10.1186/1471-2458-11-447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du W, Su C, Wang H et al. Is density of neighbourhood restaurants associated with BMI in rural Chinese adults? A longitudinal study from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopinath B, Flood VM, Teber E et al. Dietary intake of cholesterol is positively associated and use of cholesterol-lowering medication is negatively associated with prevalent age-related hearing loss. J Nutr 2011;141:1355–61. 10.3945/jn.111.138610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu L, Morishima C, Ioannou GN. Dietary cholesterol intake is associated with progression of liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C: analysis of the hepatitis C antiviral long-term treatment against cirrhosis trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1661–6.e1-3. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsson SC, Virtamo J, Wolk A. Dietary fats and dietary cholesterol and risk of stroke in women. Atherosclerosis 2012;221:282–6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houston DK, Ding J, Lee JS et al. Dietary fat and cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular disease in older adults: the Health ABC Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21:430–7. 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownawell AM, Falk MC. Cholesterol: where science and public health policy intersect. Nutr Rev 2010;68:355–64. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Gao J. The Chinese total diet study in 1990. Part II. Nutrients. J AOAC Int 1993;76:1206–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations. World population prospects: the 2012 revision. 2012. http://www.un.org/popin/data (accessed Apr 2014).

- 11.Li Y, Li D, Ma CY et al. Consumption of, and factors influencing consumption of, fruit and vegetables among elderly Chinese people. Nutrition 2012;28:504–8. 10.1016/j.nut.2011.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Lee YW. Nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and dietary restriction behavior of the Taiwanese elderly. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2005;14:221–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger S, Raman G, Vishwanathan R et al. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:276–94. 10.3945/ajcn.114.100305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyka J, Biernat J, Mikołajczak J et al. Assessment of dietary intake and nutritional status (MNA) in Polish free-living elderly people from rural environments. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;54:44–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aghdassi E, McArthur M, Liu B et al. Dietary intake of elderly living in Toronto long-term care facilities: comparison to the dietary reference intake. Rejuvenation Res 2007;10:301–9. 10.1089/rej.2006.0530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu SJ, Chang YH, Wei IL et al. Intake levels and major food sources of energy and nutrients in the Taiwanese elderly. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2005;14:211–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu SJ, Pan WH, Yeh NH et al. Trends in nutrient and dietary intake among adults and the elderly: from NAHSIT 1993–1996 to 2005–2008. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20:251–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su C, Wang H, Wang Z et al. Status and trend of fat and cholesterol intake among Chinese middle and old aged residents in 9 provinces from 1991 to 2009. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2013;42:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang B, Zhai FY, Du SF et al. The China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1989–2011. Obes Rev 2014;15(Suppl 1):2–7. 10.1111/obr.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popkin BM, Du S, Zhai F et al. Cohort Profile: The China Health and Nutrition Survey--monitoring and understanding socio-economic and health change in China 1989–2011. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:1435–40. 10.1093/ije/dyp322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang HJ, Wang ZH, Zhang JG et al. Trends in dietary fiber intake in Chinese aged 45 years and above, 1991–2011. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:619–22. 10.1038/ejcn.2014.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones-Smith JC, Popkin BM. Understanding community context and adult health changes in China: development of an urbanicity scale. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1436–46. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P et al. Global, regional, and national consumption levels of dietary fats and oils in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys. BMJ 2014;348:g2272 10.1136/bmj.g2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su C, Jia X, Wang Z et al. Trends in dietary cholesterol intake among Chinese adults: a longitudinal study from the China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1991–2011. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007532 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linseisen J, Welch AA, Ocké M et al. Dietary fat intake in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition: results from the 24-h dietary recalls. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63(Suppl 4):S61–80. 10.1038/ejcn.2009.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mead A, Atkinson G, Albin D et al. Dietetic guidelines on food and nutrition in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease—evidence from systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (second update, January 2006). J Hum Nutr Diet 2006;19:401–19. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2006.00726.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lallukka T, Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O et al. Multiple socio-economic circumstances and healthy food habits. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:701–10. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giskes K, Lenthe Fv, Brug HJ et al. Dietary intakes of adults in the Netherlands by childhood and adulthood socioeconomic position. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:871–80. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fure S. Five-year incidence of coronal and root caries in 60-, 70-, and 80-year-old Swedish individuals. Caries Res 1997;31:249–58. 10.1159/000262408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reiley JL III, Gilbert GH, Heft MW. Health care utilization by older adults in response to painful orofacial symptoms. Pain 1999;81:67–75. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00270-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]