Abstract

We describe two young immunocompetent women presenting with bilateral retinitis with outer retinal necrosis involving posterior pole with centrifugal spread and multifocal lesions simulating progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) like retinitis. Serology was negative for HIV and CD4 counts were normal; however, both women were on oral steroids at presentation for suspected autoimmune chorioretinitis. The retinitis in both eyes responded well to oral valaciclovir therapy. However, the eye with the more fulminant involvement developed retinal detachment with a loss of vision. Retinal atrophy was seen in the less involved eye with preservation of vision. Through these cases, we aim to describe a unique evolution of PORN-like retinitis in immunocompetent women, which was probably aggravated by a short-term immunosuppression secondary to oral steroids.

Background

Retinitis has been reported to be caused due to various infective and non-infective aetiologies, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), measles, syphilis, candida, sarcoidosis, masquerade syndromes and diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis.1 Well-described patterns of retinitis include acute retinal necrosis (ARN),2 3 cytomegaloviral retinitis,4 retinitis in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis and progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN).5 ARN and PORN are considered to be distinct clinical entities at opposite ends of the spectrum of necrotising herpetic retinopathies (NHR). While PORN is caused by VZV seen exclusively in AIDS patients, ARN is generally seen in immunocompetent patients caused by HSV and VZV. Here we describe two immunocompetent hosts who manifested a PORN-like retinitis.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 19-year-old woman was referred to our uvea clinic with a diagnosis of chorioretinitis and was on oral steroids (1 mg/kg body weight). She initially reported of rapid painless diminution of vision in the left eye (LE) around 15 days back. Records available with her revealed that the visual deterioration had initially started in the left eye and, after few days of steroids, the right eye (RE) also became involved and worsened at a faster pace than the left eye. There was no history of trauma, fever, prodromal illness, skin rashes, oral or genital ulcers and any systemic infection. Her best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was finger counting close to face in the RE and 20/200 in the LE when she presented to us. On examination, there were occasional anterior chamber (AC) cells and a clear media in either eye. RE showed a large placoid area of deep retinal necrosis spreading from the temporal margin of the optic disc to the major vascular arcades, without optic nerve or vascular involvement. There was no history of measles in childhood.

Investigations

An apparent cherry red spot was visible because of whitening of surrounding retina in RE (figure 1A). LE revealed a patch of retinitis at the macula with activity at its margins and pigmentary changes (figure 2A). The peripheral retinal examination was unremarkable in both the eyes. The fundus fluorescein angiography of the RE revealed mild perivenular leakage and staining at the posterior pole (figure 1B). However, no abnormality in the arterial flow or foveal avascular zone was appreciated. The LE showed window defects in the area of pigmentary changes. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) at this stage through the lesion at the right macula showed a thickened hyper-reflective retina with underlying intraretinal fluid and an overlying localised separation of posterior hyaloid with inflammatory cells in the preretinal area (figure 1C). The attachment of the posterior hyaloid was seen in the fundus photo of the RE just temporal to the white retina (figure 1A, arrow). The LE had significant retinal atrophy at the macula with few intraretinal cysts at the nasal margin of the atrophic area. Few inflammatory cells were evident in the posterior vitreous of this eye (figure 2B).

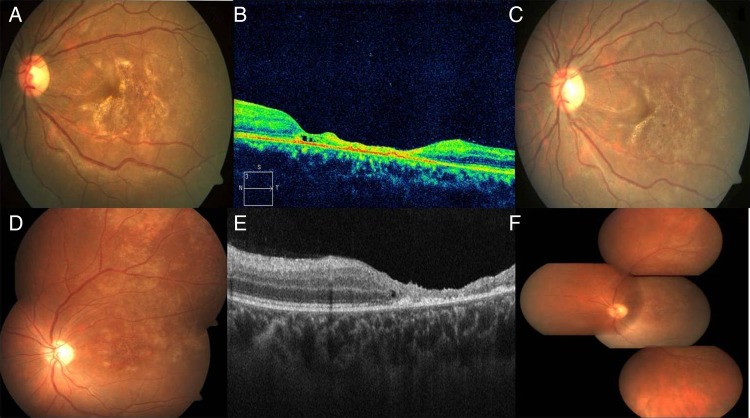

Figure 1.

The right eye of case 1 on presentation showed a whitish patch at the posterior pole with an apparent cherry red spot. There was an area of separated posterior hyaloid (arrow) surrounding this area (A). Corresponding fluorescein angiogram showed perivenular staining and no arteriolar occlusion (B). The optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the same eye showed diffuse retinal hyper-reflectivity, elevated fovea with underlying fluid, with subhyaloid inflammatory cells (C). One week after the presentation the right eye showed pallor of the optic disc, and spreading of the white necrotic retinitis patches centrifugally, having an active edge (D). The OCT at that time showed retinal schitic cavity formation, with areas of inner retinal necrosis and hole formation (arrow). Cells were evident between the posterior hyaloid and inner retina (E). At 1 month follow-up, the right eye had developed retinal detachment, optic disc pallor and subretinal proliferative vitreoretinopathy (F).

Figure 2.

At presentation pigmentary changes with fine yellowish golden dots were seen at the macula of the left eye in case 1 (A). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the same eye revealed significant retinal atrophy at the macula with few intraretinal cysts at the nasal margin of the atrophic area. Few hyper-reflective dots suggestive of cells were seen in the posterior vitreous (B). Within 3 days the yellowish golden deposits at the macula of the left eye started reducing, the area of retinal pigment epithelial alteration started becoming more localised with distinct demarcation (C). The left eye of case 2 at presentation showed pigmentary changes, punctate intraretinal haemorrhages at the macula with confluent patches of granular pigmentary changes spreading superotemporally (D). Corresponding OCT showed atrophy at the macula with few intraretinal cysts at the margin (E). At the 2nd week, the left eye showed healed retinitis both at the posterior pole and in the periphery (F).

Differential diagnosis

Infectious retinitis.

Treatment

Considering a possible diagnosis of infectious retinitis, we tapered the steroids rapidly and investigated to rule out any systemic infectious aetiology.

Outcome and follow-up

At 1 week of follow-up, serology was negative for HIV and syphilis and connective tissue disorders with normal CD4 counts. Serum immunoglobins for herpesviridae were also negative. However, the patient by now had lost perception of light (PL) in the RE, and the LE was stable. There was apparent involvement of right optic nerve and the white necrotic retinitis patches started spreading centrifugally with further development of fresh multifocal patches of retinitis (figure 1D). The SD-OCT of RE showed necrotic retina with intraretinal schisis and subhyaloid cells (figure 1E). Media was still clear with no evidence of arteriolitis or periphlebitis. A diagnosis of PORN-like retinitis was made. A vitreous tap was conducted from the RE and sent for bacterial, fungal culture; and HSV, VZV, CMV and fungal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) which was negative for any virus or fungi. The patient was empirically started on oral valaciclovir 1000 mg thrice daily. One week after antiviral therapy, lesions became more localised with distinct demarcation and progression stopped. As in the left eye, the fovea was spared the vision improved to 20/40 within 3 days (figure 2C). The retinitis in the RE also started healing; however, a retinal detachment ensued and optic atrophy developed at 1 month (figure 1F). We reduced the dose of valaciclovir after 3 weeks of therapy and stopped it after 2 months. At 3-month follow-up, the vision in the left eye was maintained at 20/40.

Case 2

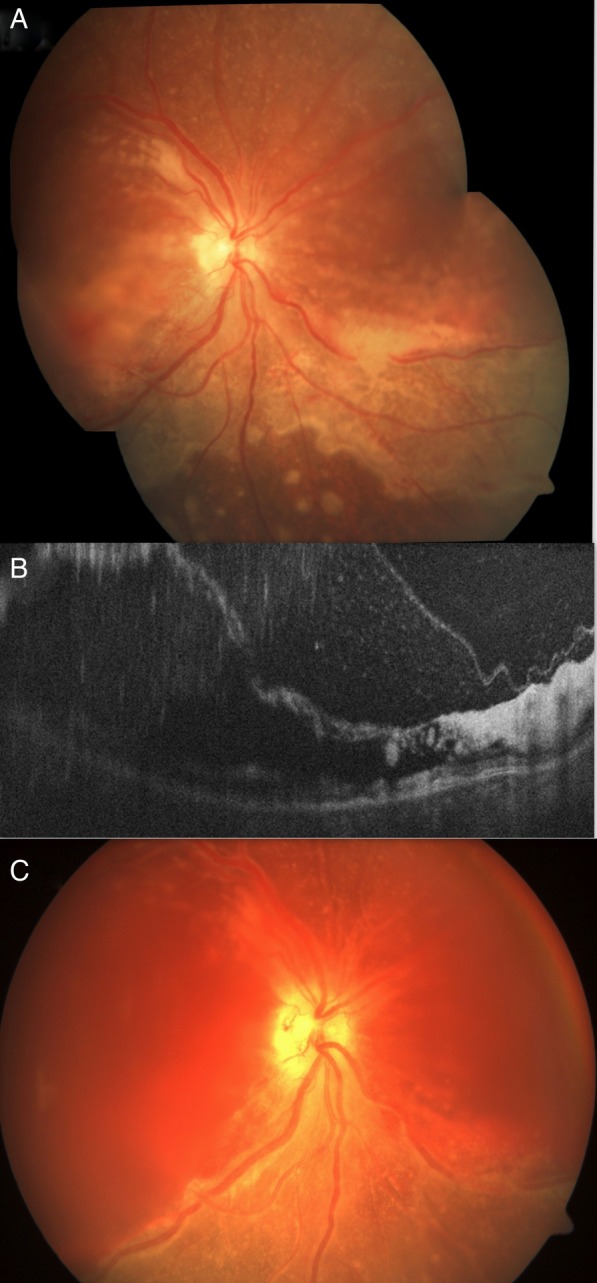

An 18-year-old woman presented with similar symptoms of rapid diminution of vision in LE for 3 weeks followed by RE. She had no other positive ocular or systemic history. She was also diagnosed as chorioretinitis and was started on oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day elsewhere and was referred to us. At presentation to our centre, the BCVA in RE was only PL and the LE had 20/200 vision. There was no history of measles in childhood. Both eyes showed occasional AC cells and retrolental cells. The RE showed thin elevated retina at the posterior pole with whitish discolouration, mild intraretinal haemorrhage inferior to the macula, centrifugally spreading retinitis with an active anterior margin. Few separate multifocal round active whitish lesions were also seen beyond the central area of involvement (figure 3A). The LE showed pigmentary changes, punctate intraretinal haemorrhages at the macula with confluent patches of granular pigmentary changes spreading superotemporally (figure 2D). More peripheral to this in the LE, there were patches of whitish confluent areas of active retinitis. There was no clinically evident vasculitis.

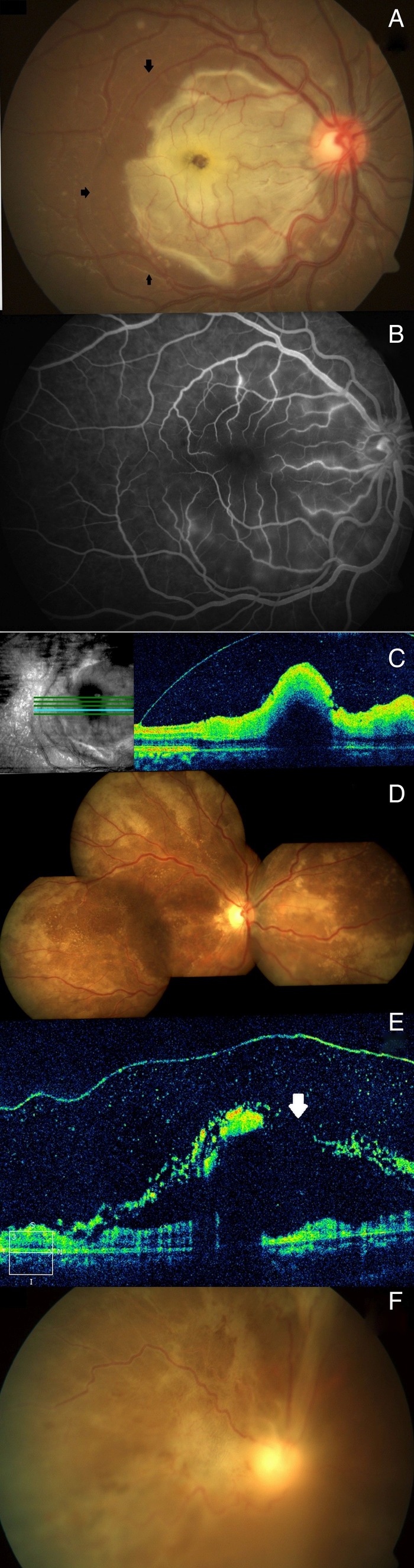

Figure 3.

The right eye of case 2 at presentation showed thin elevated retina at the posterior pole with whitish discolouration, mild intraretinal haemorrhage inferior to the macula with centrifugally spreading retinitis with an active anterior margin. Few separate multifocal round active whitish lesions were also seen beyond the central area of involvement (A). The optical coherence tomography of the right eye revealed intraretinal schisis with hyper-reflective inner retinal layers and accumulated cells between the inner retina and posterior hyaloid (B). At 4th day, case 2 presented with haemorrhage in the schitic cavity at the posterior pole with necrotic retina and multiple breaks, vitreous haemorrhage but resolving retinitis (visible inferonasal part of fundus) in the right eye (C).

Investigations

The SD-OCT of the RE revealed similar retinal thickening with intraretinal fluid and retinal schisis and accumulated cells in preretinal space (figure 3B). The LE showed atrophy at the macula with few intraretinal cysts at the margin (figure 2E). The PCR assay for viruses and fungi was negative in this case also.

Treatment

We stopped oral steroids and started the patient on oral valaciclovir 1000 mg thrice daily.

Outcome and follow-up

At 4th day, the patient came with what looked like a haemorrhage in the schitic cavity at the posterior pole with necrotic retina and breakthrough vitreous haemorrhage but in the visible inferonasal part of the right eye fundus, the retinitis appeared to be resolving (figure 3C). The left eye also started showed healing of the retinitis. Serology for HIV and syphilis was negative with normal CD4 counts. There was definite serum IgM positivity for HSV whereas serum IgM was negative for CMV and VZV. Serum IgG, however, was positive for HSV, VZV and CMV. PCR from the vitreous biopsy specimen of the RE was negative for CMV, HSV and VZV. At 2-weeks' follow-up, the RE of the patient lost PL and developed a vitreous haemorrhage with retinal detachment on ultrasound. The lesions of the LE, on the other hand, healed significantly and patient retained 20/200 vision (figure 2F). A neurological evaluation and EEG were unremarkable for the patient.

Discussion

Forster et al first described PORN as a unique identity which is characterised by discrete multifocal necrotic lesions that predominantly involve posterior outer retina with subsequent centrifugal spread with minimal to no intraocular inflammation. Eventually later in the disease process, inner retinal layers and retinal vessels are also involved.6 It is caused by VZV and seen in patients with AIDS with CD4 T-lymphocyte counts less than 10 cells/mm3 of blood. Engstrom et al had described the clinical features of PORN in a large series in which all eyes had multifocal, discrete lesions of the outer retinal layers that rapidly coalesced over days or weeks. One-third of these presented with macular involvement.5 Two-fifths of all patients present with bilateral disease and rest eventually develop bilateral disease.5

Our two patients also had similar rapidly spreading bilateral lesions causing outer retinal necrosis with macular involvement. We also found reports of retinitis patients presenting with deep retinal lesions with prominent perifoveal retinal oedema or whitened necrosis giving the appearance of a cherry red spot as seen in our first patient.7

Characteristically, PORN is associated with minimal to no inflammatory response. However, Engstrom et al5 had described fine keratic precipitates in 11% and vitreal cells in 25% of involved eyes. Media was clear with minimal inflammation in terms of few AC and vitreous cells and absence of keratic precipitates in both our patients. The course of the disease is very rapid and, generally, involves the whole of the retina and vessels and a retinal detachment develops because of necrotic breaks in most of these cases. Only, occasionally retinal haemorrhages have been described.7 8 Both of our patients had developed retinal detachment within 1 month of initial diagnosis in one eye leading to complete loss of vision. Our second patient also had developed deep retinal haemorrhages that appeared to be intraretinal in a schitic cavity within the retinal layers. This haemorrhage further broke through into the vitreous along with the development of a retinal detachment. Optic nerve abnormalities such as disc swelling, hyperaemia and optic atrophy have been reported in PORN.5 Optic atrophy in our first case resulted in the loss of light perception in the right eye.

Thus the clinical features of our cases appear to be quite similar to PORN; however, our patients were HIV negative with normal CD4 counts. We can only speculate that both the patients were immunosuppressed for a short period due to oral steroids which were started outside considering the diagnosis of chorioretinitis. Both these cases seem to have developed a viral retinitis which worsened dramatically due to the use of steroids without any antiviral therapy early in the course of the disease in these patients. Studies have shown that glucocorticoids can suppress T-cell immunity and immune responses required for antiviral immunity.9 10 Guex-Crosier et al11 have studied the role of immune status and its association with clinical findings of NHR. They categorised them as ARN, PORN and hybrid variants where ARN and PORN are extreme ends with immunocompetent and compromised status, respectively, and hybrid variants exist with clinical features in between them.11 The level of immunosuppression may prevent or limit occlusive vasculopathy and prominent ocular inflammation in PORN.12

Progressive necrotising retinitis has been described in HIV-negative patients earlier due to transient immune deviation.13 The case reported was also on glucocorticoids (60 mg prednisolone) without antiviral therapy prior to the final diagnosis of necrotising retinitis.13 PORN has also been reported in patients on immunosuppressive therapy (combination of azathioprine and glucocorticoids)14 and in patients with idiopathic lymphocytopenia.15 The lack of significant inflammation in the presence of retinal necrosis and the dramatic response to valaciclovir are suggestive of herpetic viral aetiology in our cases. Though the exact aetiology may be speculative as we could not demonstrate a positive viral PCR assay and the CD4 counts of our patients were normal.

We believe that in our cases, steroid-induced immunosuppression resulted in a PORN-like clinical picture of an underlying viral necrotising retinitis. Usually, PORN is difficult to control with antiviral therapy, but considering it as an intermediate entity, cessation of steroids lead to a response to antiviral therapy and we could salvage at least one eye of both patients.

The report aims to highlight the development of a unique PORN-like presentation of infective (likely herpetic) retinitis due to even short-term immunosuppression. We would thus like to stress on avoidance of steroids in lesions with a morphology which is atypical of an autoimmune chorioretinitis without ruling out an infective aetiology.

Learning points.

In cases of atypical retinitis, systemic steroids should not be started without ruling out an infective cause.

Infective retinitis can flare up even in apparently immunocompetent hosts and morphologically present in a form usually seen in immunocompromised individuals. This may be related to temporary immunosuppression due to steroids.

Infective retinitis may cause retinal schisis which may be haemorrhagic.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge the help of Dr Simakurthy Sriram and Dr Subodh Singh for their kind help in data collection and patient management.

Footnotes

Contributors: KT and RC had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. KT, RC, VG participated in acquisition of data. PV provided administrative, technical or material support. RC supervised the study. All the authors are responsible the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript. All the authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Chorich LJ III, Klisovic DD, Foster CS. Chapter 6: diagnosis of uveitis. In: Foster CS, Vitale AT, eds. Diagnosis and treatment of uveitis. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd., 2013:101–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young NJ, Bird AC. Bilateral acute retinal necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol 1978;62:581–90. 10.1136/bjo.62.9.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland GN. Standard diagnostic criteria for the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Executive Committee of the American Uveitis Society. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;117:663–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman AH, Orellana J, Freeman WR et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis: a manifestation of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Br J Ophthalmol 1983;67:372–80. 10.1136/bjo.67.6.372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engstrom RE, Holland GN, Margolis TP et al. The progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome. A variant of necrotizing herpetic retinopathy in patients with AIDS. Ophthalmology 1994;101:1488–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster DJ, Dugel PU, Frangieh GT et al. Rapidly progressive outer retinal necrosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;110:341–8. 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)77012-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margolis TP, Lowder CY, Holland GN et al. Varicella-zoster virus retinitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;112:119–31. 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)76690-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morley MG, Duker JS, Zacks C. Successful treatment of rapidly progressive outer retinal necrosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;117:264–5. 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)73090-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis TE, Kis-Toth K, Szanto A et al. Glucocorticoids suppress T cell function by up-regulating microRNA-98. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1882–90. 10.1002/art.37966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elftman MD, Hunzeker JT, Mellinger JC et al. Stress-induced glucocorticoids at the earliest stages of herpes simplex virus-1 infection suppress subsequent antiviral immunity, implicating impaired dendritic cell function. J Immunol 2010;184:1867–75. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guex-Crosier Y, Rochat C, Herbort CP. Necrotizing herpetic retinopathies. A spectrum of herpes virus-induced diseases determined by the immune state of the host. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 1997;5:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spaide RF, Martin DF, Teich SA et al. Successful treatment of progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome. Retina 1996;16:479–87. 10.1097/00006982-199616060-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim W-K, Chee S-P, Nussenblatt RB. Progression of varicella-zoster virus necrotizing retinopathy in an HIV-negative patient with transient immune deviation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005;243:607–9. 10.1007/s00417-004-0998-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coisy S, Ebran JM, Milea D. Progressive outer retinal necrosis and immunosuppressive therapy in myasthenia gravis. Case Rep Ophthalmol 2014;5:132–7. 10.1159/000362662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta M, Jardeleza MSR, Kim I et al. Varicella zoster virus necrotizing retinitis in two patients with idiopathic cd4 lymphocytopenia. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2015;15:1–5. 10.3109/09273948.2015.1034376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]