Abstract

An 8-year-old boy presented with a 1-year history of low backache, followed by paraparesis and urinary incontinence. MRI of the thoracic spine revealed an intramedullary, intensely contrast-enhancing lesion extending from T11 to L1 vertebral level, consistent with astrocytoma, ependymoma or haemangioblastoma. A diagnosis of intramedullary chordoma was made on tissue biopsy and immunohistochemical study. This is the second report of an intramedullary chordoma without bone involvement in English literature. After 6 months of follow-up, patient showed good clinical outcome in terms of improvement in power in lower limbs and backache.

Background

Chordoma is rare, slow growing, locally aggressive tumour that is believed to arise from the remnants of the embryonic notochord, which is a rod-shaped cartilage-like structure that serves as a scaffold for the formation of the spinal column. The most common locations are sacrum and clivus, whereas involvement of the thoracic and lumbar spine comprises only 15% of cases.1 Chordoma occurring in the intramedullary portion of the spinal cord is extremely rare, and only one case had been reported previously in the literature.2

In this case report, we present a rare case of thoracic intramedullary chordoma in a young patient.

Case presentation

An 8-year-old male patient presented with insidious onset, non-traumatic low back ache of 1-year duration along with paraparesis and urinary incontinence of 3 months duration. There was no history of anorexia, fever or tubercular contact. On clinical examination, there was atrophy of all muscles in the right leg. Power in both lower limbs was 4/5 (Medical Research Council grade) at all levels except at right ankle joint (2/5). Deep tendon reflexes were absent in both lower limbs. Sensory examination was normal.

Investigations

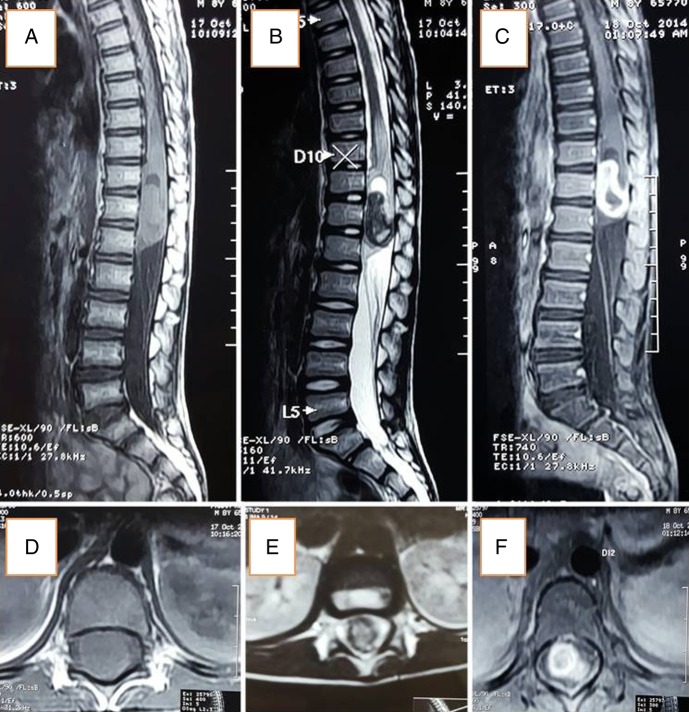

MRI of spine revealed two well-defined heterogenously enhancing lesions, isointense on T1 and hypointense on T2-weighted image along with cystic cap within the intramedullary portion of spinal cord. The extent of the lesion was T11 to L1 vertebral level involving conus medullaris with expansion of the spinal cord (figure 1A–F). Rest of the visualised vertebra was normal in height, alignment, outline and signal intensity. MRI of the brain was normal. Routine blood examination including total leucocyte count and differential leucocyte count were within normal limits. The urodynamic study showed detrusor overactivity with leak along with normal compliance.

Figure 1.

MRI showing lesion extending from T11 to L1.

Differential diagnosis

We kept a differential diagnosis of astrocytoma, ependymoma haemangioblastoma and a remote possibility of tuberculoma.

Treatment

The patient underwent T11 to L1 laminectomy. Following durotomy, the cord was found to be swollen. After performing dorsal midline myelotomy, a greyish white, firm, moderately vascular tumour with ill-defined plane between tumour and spinal cord was seen. The tumour was decompressed with the help of cavitron ultrasonic aspirator and near total excision was performed. A watertight dural closure was performed.

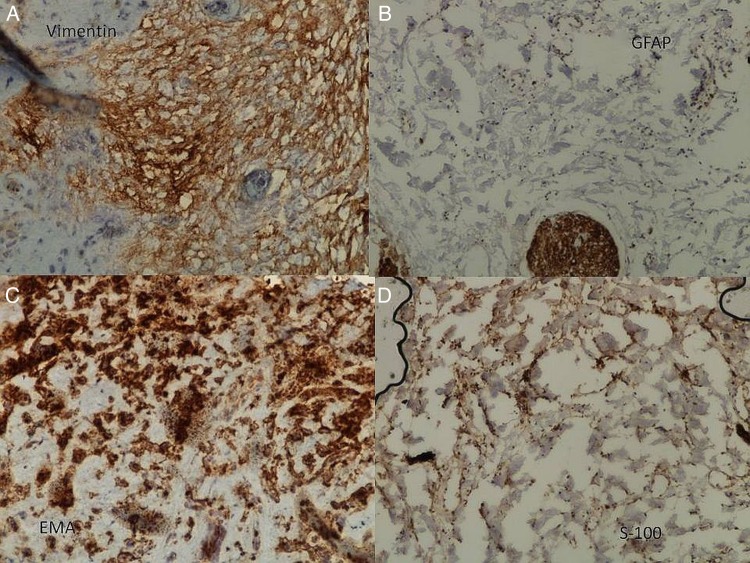

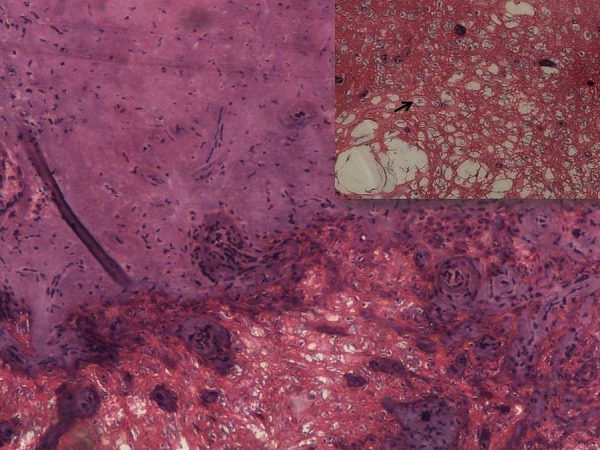

Histopathological examination showed tumour forming cords and whorls around blood vessels in the chondroid background. Individual tumour cells were small round to oval with vacuolated cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei that is, physaliphorous cells. On immunohistochemistry examination (IHC), tumour cells were positive for Vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and S-100, and negative for glial fibrillar acidic protein (GFAP), desmin and leucocyte common antigen (LCA) thereby confirming the diagnosis of chordoma. (figure 2), and (figure 3A–D).

Figure 2.

Section showing chondroid matrix with tumour cells arranged in cords (H&E×100) along with physaliphorus cells (Inset: H&E×400).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry: (A) Vimentin was diffusely expressed in cytoplasm of tumour cells; (B) however tumour cells were negative for GFAP, control expression was seen in adjoining glial tissue. There was expression of EMA and S-100 (C and D). EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; GFAP, glial fibrillar acidic protein.

Outcome and follow-up

In the immediate postoperative period, there was a significant reduction in pain and power improved to 4+/5 in both lower limbs. However, there was no evidence of any improvement in urinary incontinence. Patient was then referred to radiation oncology department, where he received full course of radiotherapy. At 10 months of follow-up, power remained 4+/5 with power in right ankle improved to 3/5.

Discussion

In 1857, Virchow first presented a histological description of gelatinous nodules in the prepontine region, projecting from the clivus. He suggested a cartilaginous origin for these nodules and called them as ‘ecchordosis physaliphora’.3 Moritz Ribbert did experimental studies in rabbits 40 years later and tried to analyse the hypothesis and coined the term chordoma for these nodules.4

Chordoma is an uncommon tumour that accounts for 1–4% of all primary malignant bone tumours.1 They affect males more than females in the ratio of 2:1.4 They may occur at any age, but peak incidence is in fifth or sixth decades of life. Most chordomas arise from the clivus (35%) or the sacrococcygeal regions (50%). In the spine, the sacrum is the most common site of disease, followed by the lumbar spine and then the cervical spine.1

They usually involve and destroy the bone, but are found very rarely in an intradural location without bone involvement, with only a few cases reported in the literature.5–8 The intramedullary location of chordoma is even rarer and only one case had been reported until now. It was located in cervicothoracic (C5-T3) and clinically presented with paraparesis along with sphincter involvement.2 Patients with osseous involvement usually present with symptoms related to compression of involved neural structures or other organs. Clinical manifestations are usually gradually progressive increase in pain, spinal instability, radiculopathy or pathological fracture. In contrast, intramedullary chordomas do not present as severe pain or pathological fracture rather they present as the weakness of limbs and sphincter involvement. Our patient also presented with gradually progressive weakness of limbs and sphincter involvement.

MRI is considered as the radiological study of choice for diagnosis and surgical planning. They are isointense to hypointense on T1-weighted MRI, with variable enhancement on the administration of the contrast. On T2-weighted MRI these tumours are hyperintense, but may have some heterogeneity in signal intensity because of calcification and bony sequestration. In our patient, the lesion was hypointense on T2 with cystic cap and showed strong contrast enhancement without any bony involvement.

Macroscopically, chordomas are usually grossly lobulated, soft, greyish in appearance. They are well demarcated in soft tissues but have elusive margins in bone. Microscopically they contain cords or nest of cells with partly vacuolated cytoplasm (physaliphorous cells) embedded in a myxoid matrix and extensive cartilage formation with degenerative calcification.9

On IHC examination, they show strong staining for vimentin, S-100 protein and EMA and pancytokeratin, while negative for GFAP. IHC also helps to differentiate these tumours from chondrosarcoma which stain negative for EMA, GFAP; ependymoma which stains positive for GFAP and negative for EMA; choroid meningioma which stains positive for EMA and negative for GFAP.9

Surgery is the ideal treatment for managing chordomas. The goal of surgery is total decompression but it is rarely possible to fully resect the tumour. Radiation therapy is useful in decreasing recurrence and prolongation of survival though tumour does not respond well to radiotherapy. Gross macroscopic resection during first surgery is the best predictor of survival.10 11 Chemotherapy is ineffective. According to most comprehensive population-based study, median overall survival for chordoma patients in the USA is ∼7 years and the overall 5, 10, 20 years survival rates are 68%, 40%, 13% respectively.12

Patient's perspective.

It was shocking for me when I came to know that my son had a tumour in the spine. After the operation he is able to do his routine activities, but he is not able to experience fullness in his bladder and has learned to do clean intermittent catheterization. Although, the doctor told me that he may not be able to regain his full bladder control in future, it is my sincere request to explore treatment and do more extensive research so that he may also get rid of this problem. Patient's mother

Learning points.

This is the second report of an intramedullary chordoma in the world literature.

Although extremely unusual, chordoma may occur in an intramedullary location within the spinal cord.

Generous reporting of such cases is warranted to understand its biological behaviour and long-term outcome.

Footnotes

Contributors: MF and QZ collected the material for this report. BO was the main motivating force whereas PA provided the histopathology slides.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cetas JS, Hughes SA, Delashaw JB Jr. Chordomas and chondrosarcomas. In: Winn HR. ed. Youmans neurological surgery. 6th edn China: Elsevier In; 2011:1587. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panagiotis GP, Vasilios TK, Maria DA et al. . Intramedullary cervical chordoma. J Neurosurg 2003;99(1 Suppl):137 10.3171/spi.2003.99.1.0137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellotti C, Ettorre F, Oliveri G et al. . Chordome vertebral dorsal an expansion endothoracique: traitement chirurgical d'un cas. Neurochirurgie 1986;32:86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarz SS, Fisher WS, Pulliam MW et al. . Thoracic chordoma in a patient with paraparesis and ivory vertebral body. Neurosurgery 1985;16:100–2. 10.1227/00006123-198501000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelabert-Gonzalez M, Pintos-Martines E, Caparrini-Escondrillas A et al. . Intradural cervical chordoma. Case report. J Neurosurg Sci 1999;43:159–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katayama Y, Tsubokawa T, Hirasawa T et al. . Intraduralextraosseouschordoma in the foramen magnum region. Case report. J Neurosurg 1991;75:976–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramiro J, Ferreras B, Perez Calvo JM et al. . Thoracic intraduralchordoma. Surg Neurol 1986;26:571–2. 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90342-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaz RM, Pereira JC, Ramos U et al. . Intradural cervical chordoma without bone involvement. Case report. J Neurosurg 1995;82:650–3. 10.3171/jns.1995.82.4.0650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menezes AH. Tumours of craniovertebral junction. In: Winn HR. ed. Youmans neurological surgery. 6th edn China: Elsevier In, 2011:3119. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Maio S, Temkin N, Ramanathan D et al. . Current comprehensive management of cranial base chordomas: 10-year meta-analysis of observational studies. J Neurosurg 2011;115:1094–105. 10.3171/2011.7.JNS11355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sciubba DM, Cheng JJ, Petteys RJ et al. . Chordoma of the sacrum and vertebral bodies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17:708–17. 10.5435/00124635-200911000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM et al. . Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973–1995. Cancer Causes Control 2001;2:1–11. 10.1023/A:1008947301735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]