Abstract

A 17-year-old Pakistani female patient presented with acute onset flaccid quadriparesis with nerve conduction studies showing demyelinating polyneuropathy consistent with Guillain-Barre’ syndrome. She was treated with 4 plasmapheresis sessions. She developed raised blood pressure, headache, visual loss and generalised seizures on the 13th day of admission. MRI of the brain on contrast showed findings of altered signals low on T1-weighted image, high on T2-weighted image and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery in the white matter of bilateral occipital, parietal and right frontal lobe consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. The patient was administered antiepileptic and antihypertensive drugs to control seizures and blood pressure. She was discharged in a stable state. On follow-up her visual loss had recovered completely and she had regained full motor strength in all four extremities after 6 weeks. Fresh MRI of the brain revealed complete resolution of lesions. Antihypertensive and antiepileptic medication was discontinued. She is independent in all her daily activities.

Background

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinicoradiological syndrome defined by the presence of headache, altered mentation, seizures and visual dysfunction. It is commonly associated with hypertension, eclampsia, vasculitis, metabolic disturbances and drugs such as chemotherapeutic agents and immunomodulatory therapy. PRES occurring as a complication of Guillain-Barre’ syndrome (GBS) or preceding it is a rare entity with very few cases reported in the literature. So far to the best of our knowledge this is the 13th case of this very rare coexistence being reported, during the hospitalisation-treatment phase. It is proposed that GBS with autonomic dysfunction is a risk factor for the development of PRES. Clinicians must therefore, be aware that either of these two can precede each other so that prompt and adequate measures are taken to avoid the resultant morbidity and mortality.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old Pakistani female patient presented with a 5-day history of weakness of all four extremities. This weakness was acute onset, progressive, ascending (involved the lower extremities first and then progressed to involve the upper extremities) and painless in nature. This ictus was preceded by a diarrhoeal illness 2 weeks prior to presentation. Family and social history were unremarkable.

On physical examination she had a pulse of 86 bpm and blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg with no postural drop. On neurological examination her Glasgow Coma Scale was 15/15. Cranial nerves were intact and symmetric. On limb examination she had flaccid quadriparesis with motor strength of 3/5 in all four extremities, areflexia with flexor plantar response. Rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable. She was diagnosed clinically and electrophysiologically as a case of GBS. Plasmapheresis was initiated accordingly.

On the 13th postadmission day after four sessions of plasmapheresis, her blood pressure showed a persistent rising trend with a maximum recording of 160/100 mm/Hg. Her heart rate was also fluctuating. Later that night she developed severe headache, vomiting and bilateral visual loss followed by two episodes of generalised tonic, clonic seizures. After regaining consciousness her visual acuity was reduced to 6/36 on the left side and hand movements on the right side. Her funduscopic examination revealed bilateral mild papilloedema.

Investigations

Laboratory workup including a complete blood count and metabolic panel with liver function tests, renal function tests, serum electrolytes (including calcium and magnesium) and blood sugar random were within normal limits. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal. Her ECG and chest X-ray were unremarkable. Antinuclear antigen was negative and hepatitis B and hepatitis C serology were non-reactive. Her nerve conduction studies were consistent with acute-inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. The motor nerves showed prolongation of distal latencies with slowing of conduction velocities. The left tibial nerve showed temporal dispersion. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis yielded cyto-protein dissociation (CSF protein of 63 mg/dL with 2 white cell counts).

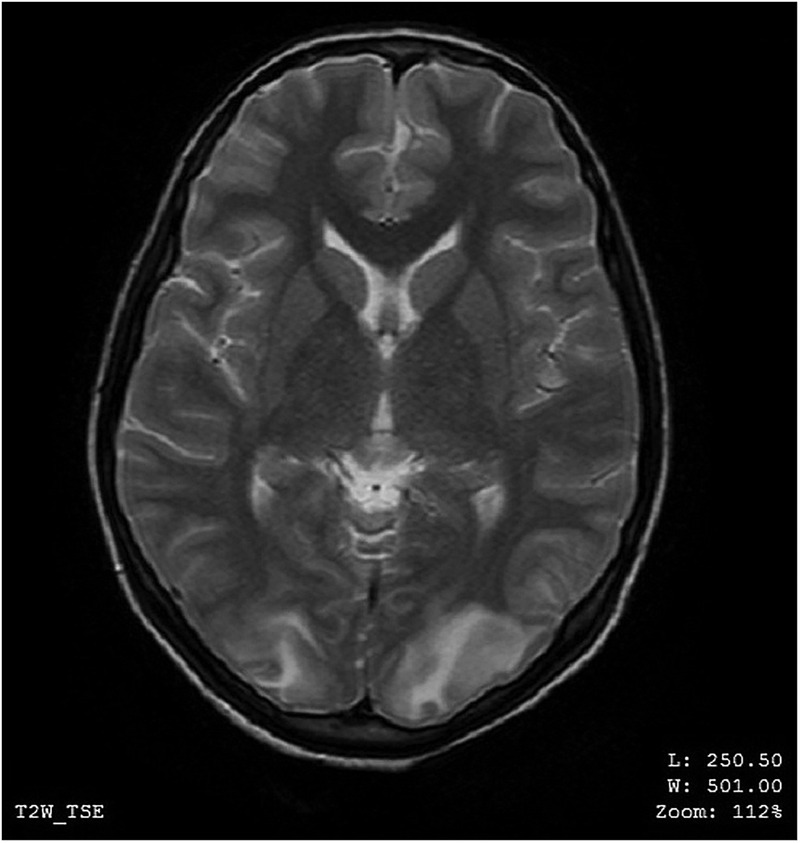

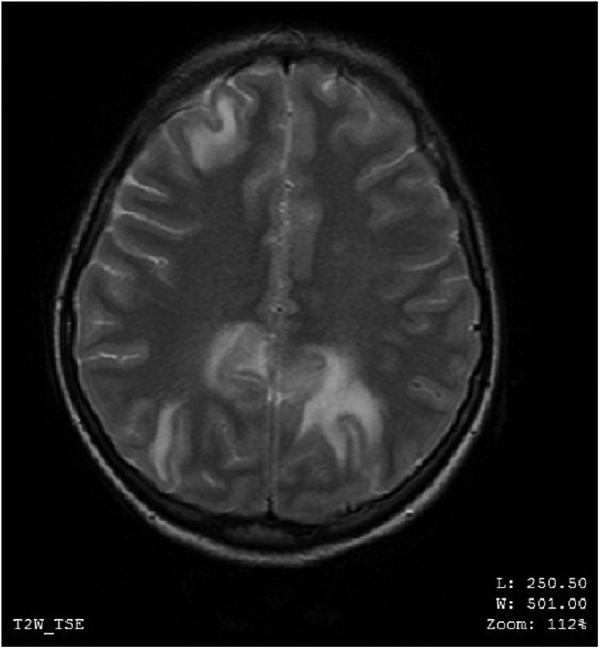

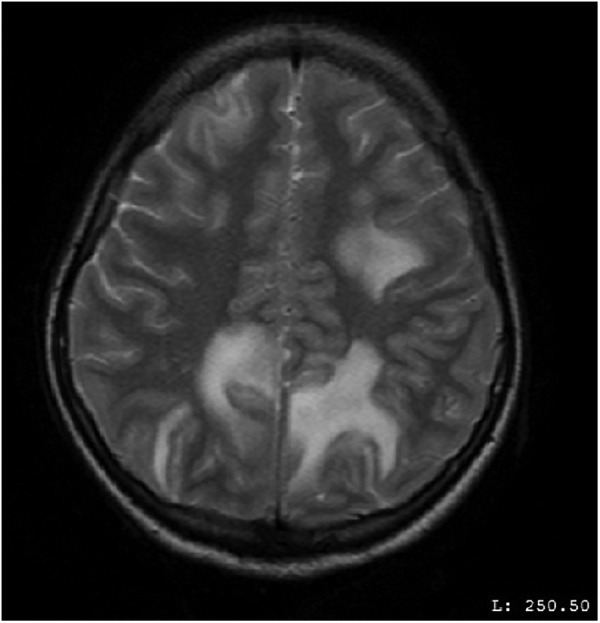

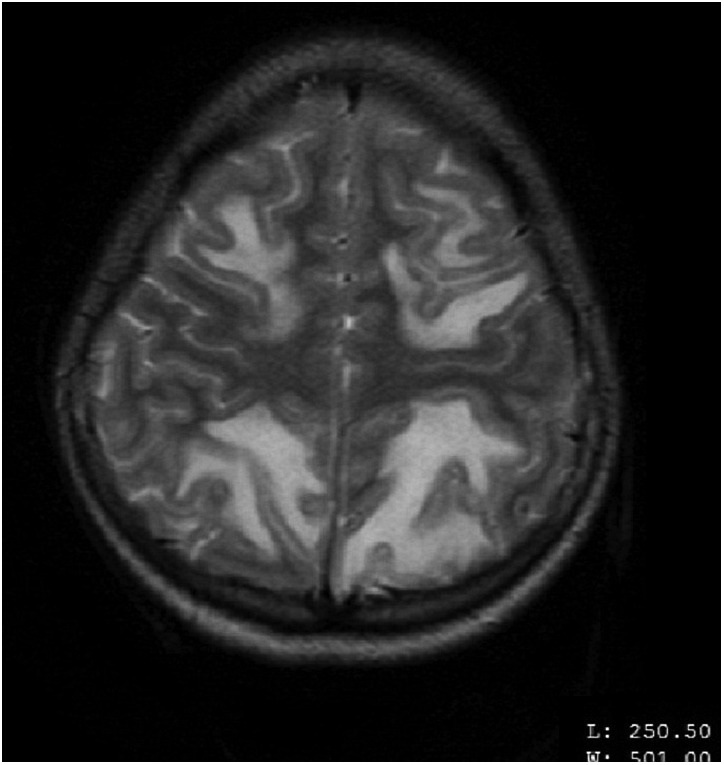

MRI of the brain on contrast showed findings of altered signals low on T1-weighted image (T1WI), high on T2-weighted image (T2WI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) in the white matter of bilateral occipital, parietal and right frontal lobe (figures 1–4). These lesions did not enhance on contrast. In the aforementioned areas increased signal intensity was noted on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sequences whereas the diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) remained normal. MR angiography (MRA) and MR venography (MRV) were normal. Her interictal EEG was normal.

Figure 1.

MRI of the brain—axial view—altered MR signals (high on T2-weighted image) in the white matter of bilateral occipital lobes.

Figure 2.

MRI of the brain—axial view—altered MR signals (high on T2-weighted image) in the white matter of bilateral occipital and right frontal lobe.

Figure 3.

MRI of the brain—axial view—altered MR signals (high on T2-weighted image) in the white matter of bilateral parietal and frontal lobes.

Figure 4.

MRI of the brain—axial view—altered MR signals (high on T2-weighted image) in the white matter of bilateral parietal and frontal lobes.

Differential diagnosis

Initially when the patient presented to our hospital two differentials were considered that is, GBS and hypokalaemic paralysis. The workup favoured the diagnosis of GBS with her nerve conduction studies showing acute-inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and CSF analysis revealing cyto-protein dissociation.

For the latter clinical event we considered posterior circulation stroke, PRES, cortical venous thrombosis and encephalitis. However, neuroimaging studies showed signal changes characteristic of PRES with a normal MRA and MRV.

Treatment

GBS was treated with four sessions of plasmapheresis performed on alternate days. In total of 250 mL/kg plasma was removed (over 4 sessions). She remained stable during the sessions with no evidence of autonomic dysfunction. Along with this prophylactic anticoagulation was administered to prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and indoor physiotherapy sessions were carried out. Once she developed PRES regular blood pressure and pulse monitoring were carried out in the intensive care setup. Intravenous levetiracetam was used to control seizures and her blood pressure was managed accordingly with tablet propranolol 20 mg twice daily and injection labetolol on demand.

Outcome and follow-up

Seizures and blood pressure were controlled with medication. The patient was discharged in a stable state after 25 days of hospitalisation. Her muscle strength had improved to 4/5 in all four limbs. She came to the neurology clinic 6 weeks later for follow-up. Her visual loss had recovered completely and she had regained full motor strength in all four extremities. Fresh MRI of the brain showed complete resolution of the initial lesions. Antihypertensive and antiepileptic medication was hence discontinued. She is independent in all her daily activities.

Discussion

Our case illustrates one of the rarest reported complications of GBS that is, PRES. PRES is a clinicoradiological syndrome defined by the presence of headache, altered mentation, seizures, visual dysfunction and focal neurological deficits.1 PRES is commonly associated with hypertension, eclampsia, vasculitis, metabolic disturbances, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, haemolytic uraemic syndrome and drugs such as chemotherapeutic agents and immunomodulatory therapy. It is characterised by signature MRI of the brain findings which include symmetric vasogenic oedema that appears low on T1WI and high on T2WI and FLAIR with little or no contrast enhancement. It typically involves the parieto-occipital white matter as seen in our patient.2 These lesions completely resolve with management of the underlying cause.

GBS is a postinflammatory disease entity involving the peripheral nerves with reported estimates of incidence varying from 0.16 to 3.0/100 000 person-years.3 This polyradiculoneuroapthy has several known complications including cranial nerve palsies, autonomic dysfunction and respiratory failure.4 Central complications such as altered sensorium and seizures are not seen in GBS. PRES can occur as a complication of GBS itself or its treatment that is, intravenous immunoglobulin (IG) or it can even precede the onset of GBS in some cases.5 6 However in either case it is a rare entity with very few cases reported in the literature. So far to the best of our knowledge this is the 13th case of this very rare coexistence being reported. There is a review article published in the Journal of Clinical Neuroscience in 2015 which reports the 12th case and reviews all the previously reported 11 cases.7

The pathogenesis of PRES itself remains unclear. The proposed aetiological mechanisms include endothelial cell dysfunction, failure of cerebral autoregulation and cerebral ischaemia.8 Impaired cerebral autoregulation is seen in the setting of acute rise in blood pressure like in cases of eclampsia and autonomic dysfunction. This leads to raised cerebral blood flow and vasogenic oedema. This is the possible pathogenesis of PRES developing in patients of GBS with dysautonomia.9 All the previously reported cases have proposed and supported this mechanism. The review article on PRES with GBS highlights that 91% cases were reported in females over 55 years.7 They suggested a possible increased sensitivity to dysautonomia in this particular group of patients. Our case however, is different as the patient was only 17 years. In most patients, symptoms of GBS preceded the onset of PRES by an average duration of 6 days. In three cases PRES occurred first followed by GBS.9 Our patient developed PRES after 18 days of onset of sensorimotor symptoms of GBS.

Another proposed mechanism of the development of PRES in patients of GBS includes treatment with intravenous IG. It is postulated that intravenous IG administration can lead to hyperviscosity, hypercoagulopathy and platelet hyperactivity which in turn causes PRES. The literature also suggests the role of cytokines in altering the permeability of the blood—brain barrier leading to PRES. In either case PRES is a rare complication of intravenous IG therapy in GBS.10 11

The treatment is supportive with correction of the underlying cause.12 Symptomatic therapy includes administration of antihypertensives to control blood pressure and antiepileptics for the treatment of seizures. The management of hypertension is the most vital step in the treatment of PRES. With prompt diagnosis and adequate management, a good prognosis and outcome has been observed in these cases including our patient.4

Learning points.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinicoradiological syndrome defined by the presence of headache, altered mentation, seizures and visual dysfunction and characteristic MRI of the brain findings.

PRES occurring as a complication of Guillain-Barre’ syndrome (GBS) or preceding it is a rare entity.

Autonomic dysfunction in GBS is a risk factor for the development of PRES.

Clinicians must be aware of this rare clinical association.

Prompt and adequate management is of paramount importance in order to avoid the resultant morbidity and mortality.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fischer M, Schmutzhard E. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 2016;111:417–24. 10.1007/s00063-016-0175-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobson EV, Craven I, Blank SC. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a truly treatable neurologic illness. Perit Dial Int 2012;32:590–4. 10.3747/pdi.2012.00152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sejvar JJ, Baughman AL, Wise M et al. Population incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 2011;36:123–33. 10.1159/000324710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banakar BF, Pujar GS, Bhargava A et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2014;5:63–5. 10.4103/0976-3147.127877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bavikatte G, Gaber T, Eshiett MU. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome as a complication of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Clin Neurosci 2010;17:924–6. 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elahi A, Kelkar P, St Louis EK. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome as the initial manifestation of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Neurocrit Care 2004;1:465–8. 10.1385/NCC:1:4:465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen A, Kim J, Henderson G et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:914–16. 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fugate JE, Claassen DO, Cloft HJ et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: associated clinical and radiologic findings. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:427–32. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackburn D, Chavada G, Dunleavy D et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) presenting with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:e4 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300645.30 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etxeberria A, Lonneville S, Rutgers MP et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome as a revealing manifestation of Guillain-Barre syndrome. Rev Neurol 2012;168:283–6. 10.1016/j.neurol.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathy I, Gille M, Van Raemdonck F et al. Neurological complications of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy: an illustrative case of acute encephalopathy following IVIg therapy and a review of literature. Acta Neurol Belg 1998;98:347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Incecik F, Hergüner MO, Altunbasak S et al. Reversible posterior encephalopathy syndrome due to intravenous immunoglobulin in a child with Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Pediatr Neurosci 2011;6:138–40. 10.4103/1817-1745.92841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]