Abstract

We investigated whether being attacked physically due to one's gender identity or expression was associated with suicide risk among trans men and women living in Virginia. The sample consisted of 350 transgender men and women who participated in the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Survey (THIS). Multivariate multinomial logistic regression was used to explore the competing outcomes associated with suicidal risk. Thirty-seven percent of trans men and women experienced at least one physical attack since the age of 13. On average, individuals experienced 3.97 (SD = 2.86) physical attacks; among these about half were attributed to one's gender identity or expression (mean = 2.08, SD = 1.96). In the multivariate multinomial regression, compared to those with no risk, being physically attacked increased the odds of both attempting and contemplating suicide regardless of gender attribution. Nevertheless, the relative impact of physical victimization on suicidal behavior was higher among those who were targeted on the basis of their gender identity or expression. Finally, no significant association was found between multiple measures of institutional discrimination and suicide risk once discriminatory and non-discriminatory physical victimization was taken into account. Trans men and women experience high levels of physical abuse and face multiple forms of discrimination. They are also at an increased risk for suicidal tendencies. Interventions that help transindividuals cope with discrimination and physical victimization simultaneously may be more effective in saving lives.

Keywords: Gender-based discrimination, Physical violence, Transgendered, Institutional discrimination

Highlights

-

•

Thirty-seven percent of transmen and women experienced at least one physical attack.

-

•

Physical victimizations averaged 3.97 (SD = 2.86).

-

•

Half of all physical attacks were attributed to gender identity or expression.

-

•

Being physically attacked is associated with suicidal ideation and behavior.

-

•

Individuals targeted on the basis gender have the highest risk for attempting suicide.

1. Introduction

Suicide disproportionately affects individuals with non-traditional gender identities. Studies have shown that between 16 and 32% of transgender men and women have attempted suicide (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006, Xavier et al., 2005). In comparison, the estimated suicide rate in the general U.S. population is between 1 and 6% (Oquendo et al., 2014, Bostwick and Pankratz, 2014, Kessler et al., 1999). In a population based study in Sweden, Dhejne and colleagues found that trans men and women are about five times as likely to attempt suicide and 19 times as likely to die by suicide when compared to a matched cohort (Dhejne et al., 2011). Similarly, a Dutch study found that transgender individuals are about nine times as likely to die by suicide compared to the general population (Van Kesteren et al., 1997). Studies conducted with transgender populations have also demonstrated high levels of violent physical victimizations (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006, Xavier et al., 2005, Kenagy and Bostwick, 2005), with rates ranging from 43% to 60% (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006, Grossman and D'Augelli, 2007, Ryan and Rivers, 2003). Compared to non-victims, victims of physical abuse have an increased risk for engaging in self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors (Gladstone et al., 2014, Santa Mina and Gallop, 1998). While this holds for members of the general population as well as for trans men and women more specifically (Grossman and D'Augelli, 2007, Kenagy, 2005, Morrow, 2004), physical victimization has been associated with a four-fold increase in suicide risk among trans men and women (Testa et al., 2012). Nevertheless, previous studies have not adequately controlled for factors that may be confounding the relationship between violent victimization and suicide risk among transgender populations.

Physical victimization that is experienced because of one's gender identity and expression (Fields et al., 2013) are important considerations in studies of suicide risk. Previous research has shown that sexual minority populations, including trans men and women, are subjected to alarmingly high rates of discrimination, violence, and rejection based on their gender (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006, Kenagy, 2005, Nuttbrock et al., 2010). Like race-based discrimination, gender-based discrimination is a major stressor that negatively impacts health. Individuals who routinely experience discrimination and feel that their identity is under attack are more likely to engage in suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Haas et al., 2010, Herek et al., 1999, De Graaf et al., 2006). Nevertheless, only a handful of studies have linked suicidal behavior to various aspects of gender-based discrimination among sexual minorities (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006, Bontempo and d'Augelli, 2002, Friedman et al., 2006, Goodenow et al., 2006, House AS et al., 2011). This research has suggests that transgender men and women experience the multiple forms of discrimination associated with their gender identity as interpersonal trauma. In one such study, Clements-Nolle, Marx, & Katz found that histories of both gender-based discrimination and forced sex were independently associated with attempted suicide among transgender persons (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006). Another study found that trans men and women who experienced gender-based physical victimization at school have a higher risk of attempting suicide compared to non-victims (Testa et al., 2012, Goldblum et al., 2012). No large-scale study has examined the magnitude and relative effects of both violent physical victimization and multiple forms of discrimination on the risk of suicidal ideation and behavior among transgender men and women. Given the increasingly prominent role of transgender individuals in today's society along with the potential to misunderstand this population, such studies are desperately needed (McDaniel et al., 2001). In light of this, our goals are: (a) to estimate the prevalence of physical victimization among those who were targeted on the basis of their gender identity and/or expression and among those who were not; (b) to explore the relative associations between suicidal thoughts and behaviors among those who faced discriminatory and non-discriminatory victimization and those who did not; and (c) to estimate the magnitude of the difference in effect between discriminatory and non-discriminatory victimization on suicide risk compared to no suicide risk.

2. Methods

Study participants were 350 transgender individuals living in Virginia who participated in the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Survey (THIS). Implemented by the Community Health Research Initiative of Virginia Commonwealth University, under the direction of the Virginia Department of Health and its HIV Community Planning Committee (Bradford et al., 2006, Xavier and Bradford, 2005), THIS was a multi-phase, multi-year project to improve the health of transgender Virginians. Eligible participants provided written informed consent and then completed a statewide questionnaire that included questions about health status and ability to get health care, violence exposure, substance abuse, housing, employment and HIV/AIDS. Participants were paid $15 for their time. Eligibility criterion was determined on the basis of a positive response to all three of the following questions: 1) have lived or want to live full-time in a gender opposite your birth or physical sex; 2) have or want to physically modify your body to match who you feel you really are inside; or 3) have or want to wear clothing of the opposite sex, in order to express an inner, cross-gender identity. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University.

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Violent physical victimization

Discrimination-based victimization was based on responses to two questions. Participants were asked, “Other than unwanted sexual activity, since the time you were 13 years old, have you ever been physically attacked? A physical attack includes being grabbed, punched, choked, stabbed with a sharp object, (including knives), being hit with an object (like a rock), and being shot with any type of weapon.” An affirmative response prompted the following question, “In how many of these cases was your transgender status, gender identity or expression the primary reason for the physical attack(s)?” We derived 2 measures from these questions. An endorsement that being physically attacked due to one's transgender status, gender identity or expression was coded as discrimination-related physical victimization (1 = yes; 0 = no). Non-discriminatory victimization was codified as a physical attack that was reported as not due to transgender status, gender identity or expression (i.e., the respondent did not consider the physical assault to be related to their gender) (1 = yes; 0 = no). A third variable was created to capture whether the respondent experienced any form of institutional discrimination such as having lost housing or a housing opportunity, being fired from a job, experiencing discrimination by a doctor or other health care provider, and/or denied enrollment in a health insurance plan due to transgender status or gender expression (1 = yes; 0 = no).

2.1.2. Sociodemographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics included age, education level, income, employment status, gender vector, housing situation, whether they were presently living full-time in the gender of their choice and level of family support for their gender identity expression. Gender vector is a dichotomous indicator measuring whether the respondent was on the male to female (MTF) spectrum (born male) or on the female to male (FTM) spectrum (born female). A continuous measure of educational attainment ranged from 8th grade or less (= 1) to graduate or professional degree (= 8); annual income ranged from no income (= 1) to $100,000 or more (= 11); employment status was measured as working full or part time (= 1) versus unemployed (= 0); respondents were classified as having transitioned into the gender of their choice full-time (= 1) versus planning or not planning to transition (= 0); and housing into housing instability (homeless, living rent free with friend or relative, assisted housing through a religious group, private or public agency) (= 1) versus housing stability (rent or own home or apartment) (= 0).

2.1.3. Substance use

Participants were asked about past problems with 10 illicit drugs (i.e., cocaine powder, crack cocaine, heroin, or hallucinogens, methamphetamines, PCP, and club drugs, poppers, downers, and painkillers). Respondents were also asked about past problems with alcohol. In both cases responses were recoded as 1 = yes or 0 = no.

2.1.4. Family social support

The survey also queried respondents about how supportive their family of origin is about their gender identity. Responses were recorded on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 – not supportive at all to 4 - very supportive.

2.1.5. Receiving counseling or psychotherapy

Participants self-reported whether they had ever received counseling or psychotherapy for a transgendered-related service? (1 = yes; 0 = no).

2.1.6. Suicidal risk behavior

Participants were asked if they had ever thought about killing themselves and if so were provided with a follow-up question asking if they had ever attempted suicide. Since those who attempt suicide must consider it beforehand, a completely accurate account of all participants who actually considered suicide must include both those who did and did not actually attempt it. Therefore, our analysis distinguishes between two measures of ideation - one that counts all those who considered suicide and another measure that looks at only those who considered but did not attempt it. Accordingly, we defined suicide risk in 3 ways: suicidal ideation only (thought about suicide but did not attempt it), suicidal ideation total (all those who actively considered suicide including those who attempted suicide) and suicidal behavior (attempted suicide). Individuals who neither contemplated nor attempted suicide were classified as ‘no risk for suicidal behavior’ and in the analysis below served as our referent group.

2.2. Statistical analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for all study variables. We examined means and SDs for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. We conducted bivariate tests to determine whether and to what extent discriminatory victimization, non-discriminatory victimization and institutional discrimination (in addition to several covariates) are related to suicide risk. We used a multivariate multinomial regression model to explore the relationship between suicide risk and discrimination-based victimization, non-discrimination based victimization and institutional discrimination while controlling for sociodemographic and psychosocial variables including education, income, housing stability, family support, drug and alcohol use, counseling and transition status. Post-estimation techniques were used after the final model was specified in order to predict probabilities and marginal effects of key variables.

3. Results

Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of the sample. Thirty-nine percent of the sample were under the age of 30. A majority were low socioeconomic status, with 44% unemployed, 57% with incomes less than $30,000 and 31% with less than a high school degree (Table 1). About 1 in 5 had housing situations that were unstable (e.g. homeless). Gender identity and sexual preference were highly variable. Most identified their gender as either a man (19.4%), woman (25.4%) or as transgender (41.7%) and their sexual preference as heterosexual (20.9%), gay (15.4%), lesbian (13.4%) or bisexual (17.1%). On average, 8% were HIV positive and diagnosed approximately 4 years (SD = 1.07) before the study period. Alcohol abuse characterized 25% of the sample and 62% reported past drug use. Suicidal tendencies were high with almost 64% of the sample reporting either suicidal ideation (38%) or attempting suicide (25%). About 1 in 4 participants have received psychological counseling (27%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of transgender individuals: Virginia, 2005–2006.

| Variables | % |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Age (30 or under) | 39 |

| Employed | 56 |

| Income < $30,000 | 57 |

| Education ≤ HS | 31 |

| Non-white (including multiracial) | 38 |

| Not in stable housing | 20 |

| MTF | 65 |

| FTM | 35 |

| Psychosocial characteristics | |

| Drug use, ever | 62 |

| Alcohol abuse | 25 |

| HIV diagnosis (+) | 8 |

| Any physical abuse | 37 |

| Discriminatory | 26 |

| Non-discriminatory | 11 |

| Institutional discrimination | 39 |

| Family of origin support for gender identity expression (somewhat or very supportive) | 66 |

| Suicidal thought (no attempt) | 38 |

| Suicidal attempt | 25 |

| Ever received counseling | 27 |

3.1. Experience with interpersonal victimization & discrimination

About 37% percent of participants reported experiencing physical abuse (e.g. grabbed, punched, choked, stabbed or shot) since the age of 13. The average number of physical attacks was 3.97 (SD = 2.86). Half of these incidents were attributed specifically to one's gender identity or expression (ave = 2.08, SD = 1.96). Thirty-nine percent of the sample reported at least one experience with institutional discrimination based on their gender identity or expression by being denied enrollment in a health insurance plan (6.3%), refused housing (8.3%) or a bed in a homeless shelter (2%), denied employment (18.6%), or experiencing discrimination by a doctor or other health care provider (24%).

3.2. Interpersonal victimization, discrimination and suicidal tendency

In bivariate analyses, institutional discrimination was associated with a higher likelihood of attempting suicide compared to no suicide risk (odds ratio [OR] = 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2, 3.8, p < 0.01). Compared to no risk, non-discriminatory physical victimization was associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts (OR = 4.9, CI = 1.7, 7.2, p < 0.01), suicidal ideation only (OR = 4.3, CI = 1.6, 11.8, p < 0.01) and total suicidal ideation (OR = 4.5, CI = 1.7, 11.9, p < 0.01). Discrimination-based physical victimization was associated with an increased risk of attempting suicide (OR = 5.3, CI = (2.8, 10.1), p < 0.01) and total suicidal ideation (OR = 2.7, CI = 1.5, 4.7, p < 0.01) compared to no risk (see unadjusted ORs in Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate and multivariate regressions predicting suicide risk with discrimination, physical victimization and discrimination-based physical discrimination among transgender men and women living in Virginia, 2005–2006.

| UORa (95% CI) | AORb (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional discrimination due to gender identity | ||

| Suicidal ideation only | 1.13⁎ (0.68, 1.9) | 1.1 (0.52, 2.2) |

| Suicidal ideation (total) | 1.47 (0.94, 2.3) | 1.2 (0.60, 2.3) |

| Suicide attempt | 2.2⁎⁎⁎ (1.2, 3.8) | 1.2 (0.56, 2.7) |

| Non-discriminatory victimization | ||

| Suicidal ideation only | 4.3⁎⁎⁎ (1.55, 11.8) | 4.6⁎⁎ (1.2, 17.9) |

| Suicidal ideation (total) | 4.5⁎⁎⁎ (1.7, 11.9) | 6.0⁎⁎⁎ (1.6, 22.0) |

| Suicide attempt | 4.9⁎⁎⁎ (1.7, 7.2) | 9.1⁎⁎⁎ (2.2, 12.0) |

| Discriminatory victimization | ||

| Suicidal ideation only | 1.5 (0.791, 2.9) | 1.7 (0.70, 4.0) |

| Suicidal ideation (total) | 2.7⁎⁎⁎ (1.5, 4.7) | 3.2⁎⁎⁎ (1.5, 7.0) |

| Suicide attempt | 5.3⁎⁎⁎ (2.8, 10.1) | 6.2⁎⁎⁎ (2.2, 14.6) |

The final sample size was 299.

No suicide risk is the referent category.

UOR = unadjusted odds ratio.

AOR = adjusted odds ratio.

p < 0.10.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Multivariate multinomial regression indicated that those who experienced discrimination-based physical victimization continued to be at an increased risk for attempting suicide (OR = 6.2, CI = 2.2, 14.6, p < 0.01) and for total suicidal ideation (OR = 3.2, CI = 1.5, 7.0, p < 0.01). Non-discriminatory physical victimization was associated with attempting suicide (OR = 9.1, CI = 2.2, 12, p < 0.002), suicidal ideation only (OR = 4.6, CI = 1.2, 17.9, p < 0.002) and total suicidal ideation (OR = 6.0, CI = 1.6, 22.0, p < 0.002). The inclusion of confounding variables diminished all observed multivariate associations between institutional discrimination and suicide to insignificance.

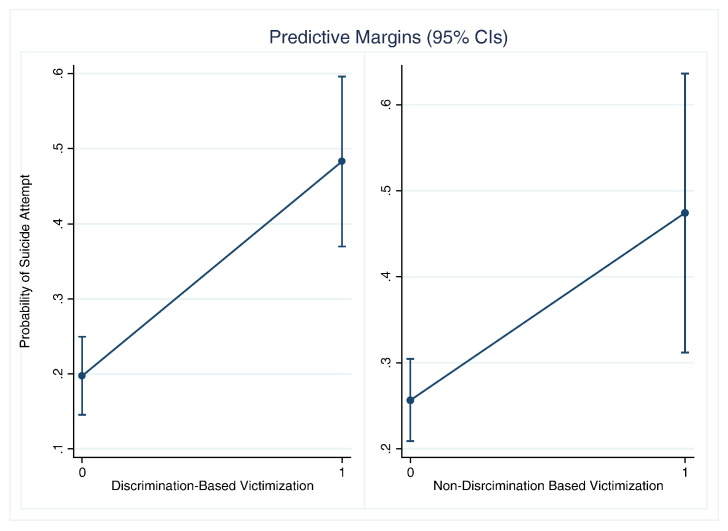

Table 3 shows the contrasts of predictive margins and confidence intervals for the probability of suicide risk when all variables in the model are at their means. As shown by the table, among trans men and women who have experienced discrimination-based physical victimization, the probability of attempting suicide is 0.483. The probability of attempting suicide among those who have not experienced discriminatory victimization is 0.197. The difference between the two probabilities provides the predictive contrast of these marginal probabilities. The difference of 0.286 (CI = 0.156, 0.415, p < 0.01) implies that discrimination-based physical victimization is associated with a 28.6% increase in the probability of attempting suicide when all other variables are held constant at their mean. Similarly, the predicted marginal probability of attempting suicide is 0.473 among those who have experienced non-discriminatory physical victimization while it is 0.256 among those who have not (See Fig. 1). The predicted marginal contrast is therefore 0.217 (CI = 0.156, 0.416, p < 0.01) implying that non-discriminatory physical victimization is associated with a 21.7% increase in the probability of attempting suicide when all variables are at their means.

Table 3.

Contrasts of predictive margins for probability of suicidal ideation and behavior among transmen and women experiencing discrimination-based physical victimization compared to non-discrimination based victimization living in Virginia, 2005–2006.

| Probability of… | Discrimination-based victimization | Non-discriminatory victimization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Predictive contrasts (95% CI) | Yes | No | Predictive contrasts (95% CI) | |

| No risk | 0.206 | 0.386 | -0.180 (− 0.289, − 0.072) | 0.118 | 0.362 | -0.244 (− 0.289, − 0.072) |

| Suicide Ideation only | 0.417 | 0.311 | 0.106 (0.019, − 0.229) | 0.407 | 0.381 | 0.026 (− 0.029, 0.030) |

| Suicide Ideation (total) | 0.385 | 0.205 | 0.179 (0.073, 0.286) | 0.363 | 0.124 | 0.239 (0.112, 0.366) |

| Suicide Attempt | 0.483 | 0.197 | 0.286 (0.156, 0.415) | 0.473 | 0.256 | 0.217 (0.156, 0.416) |

Fig. 1.

Adjusted marginal predictions of suicide attempts among transmen and women experiencing discrimination-based physical victimization compared to non-discriminatory victimization, Virginia 2005–2006.

Since this latter difference is smaller, the overall effect of discriminatory victimization on suicide attempts is about 7 percentage points higher than it is for non-discriminatory victimization. A test of the difference of these differences (i.e. contrast of predictive marginal) was not statistically significant (χ2 = 1.68, p = 0.195), however.

In the multivariate regression, compared to no risk, common variables increasing the odds of attempting suicide, suicidal ideation only and total suicidal ideation included being white (versus non-white), lower levels of perceived family support, lack of psychological counseling or psychotherapy for a trans-related service and past problems with alcohol use (see Table 4). As well, housing instability was associated with an increased risk of attempting suicide and higher levels of education were marginally associated with suicide ideation only versus no risk (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression odds ratios for sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics predicting suicidal behavior versus no suicide risk and suicidal ideation among transmen and women living in Virginia, 2005–2006.

| Attempt | Ideation only | Total ideation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 1.04 | 1.27⁎ | 1.18 |

| Housing instability | 2.8⁎⁎ | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| Age | 0.947 | 1.00 | 0.980 |

| Income | 1.01 | 0.947 | 0.979 |

| Non-white | 0.689⁎⁎⁎ | 0.236⁎⁎⁎ | 0.373⁎⁎⁎ |

| Transitioned (yes) | 1.42 | 1.32 | 1.41 |

| FTM | 1.59 | 1.94⁎ | 1.77 |

| Family support | 0.751⁎ | 0.639⁎⁎⁎ | 0.683⁎⁎⁎ |

| Received counseling | 0.496⁎ | 0.337⁎⁎⁎ | 0.401⁎⁎⁎ |

| Drug use (ever) | 0.641 | 0.932 | 0.795 |

| Alcohol use (ever) | 5.36⁎⁎⁎ | 2.65⁎⁎ | 3.57⁎⁎⁎ |

Table notes: LR χ (Xavier et al., 2005)(30) = 141.39, Prob > χ (Xavier et al., 2005)(30) < 0.001, Pseudo R (Xavier et al., 2005) = 0.220, N = 299.

No suicide risk is the referent category.

p < 0.10.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In our sample of over 300 trans men and women living in Virginia we found a high prevalence of suicide risk (63%) that included either contemplating (38%) or attempting (25%) suicide. We further found high levels of interpersonal discrimination, non-discriminatory and discriminatory physical victimization. About 37% of individuals reported being attacked physically on one or more occasions. Individuals who were physically abused reported 4 victimizations on average and half of these were attributed to gender or identity discrimination. The prevalence of gender or identity-based institutional discrimination resulting from health systems, housing or employment was similarly high (38.9%).

Previous research has shown an association between multiple forms of victimization and suicide (Santa Mina and Gallop, 1998, Fields et al., 2013, Seedat et al., 2005, Flannery et al., 2001). Research that includes the experiences of trans men and women has uncovered associations between experiencing interpersonal victimization and sexual discrimination and both suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury (House AS et al., 2011). In this paper we explored the independent effects of institutional discrimination, discriminatory victimization and non-discriminatory victimization on attempting suicide versus thinking about it or doing neither. We, too, found that experiencing physical abuse increases suicide risk. We emphasize, however, that merely attributing a physical attack to gender alone is too simplistic to explain the complexity of the relationship between violence, discrimination and gender. For example, it is highly likely that at least some physical attacks are accompanied by verbalizations clarifying that the victim's gender identity was the very reason they were targeted in the first instance. Future research would benefit by exploring the processes undergirding the relationship between gender expression (irrespective of sexual preference), violence and psychopathology among transgender men and women.

Previous research has focused on sexual minorities broadly defined as opposed to transgender men and women specifically, most probably due to the lack of data on this population. Nevertheless, the results of this study are consistent with those that have found sexual minority individuals who experience discrimination-related stressors show greater adverse mental health outcomes (e.g. suicide ideation) than those who do not face similar stressors. In accordance with previous research, we found that trans men and women who experience physical victimization due to their gender are more likely to engage in suicidal behavior than individuals who are either not victimized physically or who are physically victimized but do not attribute that experience to gender. These associations remained significant in the multivariate model after controlling for a number of sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics, including housing stability, past alcohol and drug use, family support for gender identity expression, psychological counseling and living fully in one's chosen gender. Additionally, in the multivariate models, non-discrimination-based physical abuse was highly associated with suicide risk compared to no suicide risk.

By estimating the magnitude of the competing risks associated with suicidal behavior among individuals who have experienced discrimination-based victimization, we showed that the presence of discrimination is one factor that tends to move people from a lower risk category (i.e. no risk, ideation) to a more severe one (i.e. attempt). We extended this analysis by using a variety of post-estimation techniques to quantify the difference that discriminatory and non-discriminatory victimization has on the probability of 1) no suicide risk, 2) two measures of suicidal ideation; and 3) suicide attempts. We found that the marginal probability of attempting suicide was highest for those who attributed being physically attacked to their gender identity, followed by those who were physically attacked but did not attribute it to gender identity, and then among those who reported institutional discrimination. More specifically, we found the probability of attempting suicide is 28.6 and 23.9 percentage points higher among those experiencing discriminatory and non-discriminatory victimization, respectively compared to those experiencing neither. The predictive contrasts of these relative effects on suicidal behavior suggested that discriminatory versus non-discriminatory victimization increased the risk of suicide attempt by almost 7 percentage points on average. And, while this difference was not statistically significant it is practically important as the magnitude of the difference between attempting suicide and being at no risk is higher for victims who are targeted for their gender expression or identity. At the same time, this finding suggests that some types of victimization may be so inherently stressful that they lead to negative health behaviors even after controlling for the presence of other psychosocial stressors (i.e. discrimination, housing instability, family social support). In other words, irrespective of whether the physical victimization was due to one's status as transgender or one's gender expression, the odds of contemplating or attempting suicide are significantly higher among individuals who reported at least one violent physical victimization. Therefore, minimizing physical harm perpetrated against transgender individuals must be visible in the surveillance of mental health outcomes in this population.

In addition, our analysis uncovered other factors that were highly associated with suicide risk and hence should be focal points for suicide prevention and intervention among trans men and women. The findings suggest that trans men and women require higher levels of social and therapeutic support to help them cope with pervasive discrimination and repeated victimization characterizing this population. For example, individuals with a decreased risk of suicide reported higher levels of family social support for their gender identity and/or expression and were more likely to have received counseling or psychotherapy for a transgender-related service. Moreover, housing instability contributes to suicide risk among trans men and women and therefore strategies that address homelessness, broadly defined, may also be important in suicide prevention efforts above and beyond discrimination, physical victimization and social support. Finally, it's worth noting that our finding regarding the impact of being white on suicide risk is in accordance with previous research showing a higher prevalence of attempted suicide among white populations compared to non-white populations (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006). Data limitations prevented us from exploring the underlying mechanisms and processes by which these factors increase suicide risk, so we leave this as an area for future research.

4.1. Limitations

Since THIS was not a population-based survey, our findings are not generalizable to the larger population of transpeople who are living in the United States. In addition, the survey is cross-sectional and hence time ordering is impossible to establish. We are unable to explore alternative explanations for these findings such as whether there are an observable differences in suicidal behavior across race or across race and gender. The sample size was too small in some cases to explore effects of different types of institutional discrimination or to include other variables that may be related to both discrimination and victimization on the one hand and suicide on the other. Finally, confounding may be present due to the omission of key variables despite our attempt to minimize confounding bias. As well, some of our confounding variables were crudely categorized and hence residual confounding may be present. Nevertheless, given the scarcity of data on a population that has become increasingly more visible in recent years, and who has had to struggle for acceptance and security, we believe the strengths of this study outweigh its limitations.

4.2. Conclusions

Trans men and women who experience physical victimization continue to have worse mental health outcomes compared to those who do not and are oftentimes targeted for violence on the basis of their gender identity or expression. Above and beyond the consequent harm resulting from violence, suicide risk shows associations with housing instability, lack of psychological counseling and family support, substance use and minority status. It is important to underscore the role of mental health care providers in prevention efforts since previous research has uncovered important barriers to care including negative experiences with counseling and psychotherapy. These experiences have been attributed to the social stigma of transgenderism and its associated victimization which according to the focus group findings from the THIS study are constants in the lives of most participants (Xavier and Bradford, 2005). To these participants, acceptance of gender identity was the “principal means of avoiding victimization and improving self-esteem30 (p.12),” which in turn required access and acceptance among medical care providers. Public health policy aimed at suicide prevention and intervention should focus on these factors with particular consideration to the complex dynamics and intersectionality associated with the correlates of poor mental health identified in the current investigation. In order to ensure the safety of trans men and women, it is urgent that these steps are taken.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Transparency document

Transparency document

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Fenway Community Health Center at the Fenway Institute for granting us access to data from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study (THIS).

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version.

Contributor Information

Gia Elise Barboza, Email: g.barboza@neu.edu.

Silvia Dominguez, Email: s.dominguez@neu.edu.

Elena Chance, Email: chace.e@husky.neu.edu.

References

- Bontempo D.E., d'Augelli A.R. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths' health risk behavior. J. Adolesc. Health. 2002;30(5):364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick J.M., Pankratz V.S. Affective disorders and suicide risk: a reexamination. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford J., Xavier J., Rives M.E., Hendricks M. Transgender Health in Virginia: Results From a Statewide Multi-methods Survey; Paper presented at the American Public Health Association 134th Annual Meeting and Exposition; November 4–8, 2006; Boston, MA; 2006. (Available at: http://apha.confex.com/apha/134am/techprogram/paper_141064.htm. Accessed March 9, 2012. 30) [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K., Marx R., Katz M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons: the influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. J. Homosex. 2006;51(3):53–69. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf R., Sandfort T.G., ten Have M. Suicidality and sexual orientation: differences between men and women in a general population-based sample from the Netherlands. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2006;35(3):253–262. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhejne C., Lichtenstein P., Boman M., Johansson A.L., Långström N., Landén M. 2011. Long-term Follow-up of Transsexual Persons Undergoing Sex Reassignment Surgery: Cohort Study in Sweden. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields E.L., Bogart L.M., Galvan F.H., Wagner G.J., Klein D.J., Schuster M.A. Association of discrimination-related trauma with sexual risk among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103(5):875–880. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery D.J., Singer M.I., Wester K. Violence exposure, psychological trauma, and suicide risk in a community sample of dangerously violent adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):435–442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M.S., Koeske G.F., Silvestre A.J., Korr W.S., Sites E.W. The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. J. Adolesc. Health. 2006;38(5):621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone G.L., Parker G.B., Mitchell P.B., Malhi G.S., Wilhelm K., Austin M.-P. Implications of childhood trauma for depressed women: an analysis of pathways from childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and revictimization. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldblum P., Testa R.J., Pflum S., Hendricks M.L., Bradford J., Bongar B. The relationship between gender-based victimization and suicide attempts in transgender people. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012;43(5):468. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C., Szalacha L., Westheimer K. School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 2006;43(5):573–589. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A.H., D'Augelli A.R. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2007;37(5):527–537. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A.P., Eliason M., Mays V.M. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J. Homosex. 2010;58(1):10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek G.M., Gillis J.R., Cogan J.C. Psychological sequelae of hate-crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999;67(6):945. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House AS, Van Horn E., Coppeans C., Stepleman L.M. Interpersonal trauma and discriminatory events as predictors of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender persons. Traumatology. 2011;17(2):75. [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy G.P. Transgender health: findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health Soc. Work. 2005;30(1):19–26. doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy G.P., Bostwick W.B. Health and social service needs of transgender people in Chicago. Int. J. Transgenderism. 2005;8(2–3):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Borges G., Walters E.E. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel J.S., Purcell D., D'Augelli A.R. The relationship between sexual orientation and risk for suicide: research findings and future directions for research and prevention. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2001;31(s1):84–105. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.5.84.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow D. Social work practice with gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender adolescents. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2004;85(1):91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L., Hwahng S., Bockting W. Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(1):12–23. doi: 10.1080/00224490903062258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo M.A., Ellis S.P., Greenwald S., Malone K.M., Weissman M.M., Mann J.J. Ethnic and sex differences in suicide rates relative to major depression in the United States. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C., Rivers I. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth: victimization and its correlates in the USA and UK. Cult. Health Sex. 2003;5(2):103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Mina E.E., Gallop R.M. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult self-harm and suicidal behaviour: a literature review. Can. J. Psychiatr. 1998;43:793–800. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S., Stein M.B., Forde D.R. Association between physical partner violence, posttraumatic stress, childhood trauma, and suicide attempts in a community sample of women. Violence Vict. 2005;20(1):87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa R.J., Sciacca L.M., Wang F. Effects of violence on transgender people. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012;43(5):452. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kesteren P.J., Asscheman H., Megens J.A., Gooren L.J. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual subjects treated with cross-sex hormones. Clin. Endocrinol. 1997;47(3):337–343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2601068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier J, Bradford J. Transgender Health Access in Virginia: Focus Group Report. Richmond, VA: Virginia Department of Health; 2005. Available at: http://www. vdh.state.va.us/std/Research%20Highlights/TG% 20Focus%20Group%20Report%20final%201.3.pdf. (Accessed March 13, 2010).

- Xavier J.M., Bobbin M., Singer B., Budd E. A needs assessment of transgendered people of color living in Washington, DC. Int. J. Transgenderism. 2005;8(2–3):31–47. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document