Abstract

Objectives

South Africa has pledged to the sustainable development goal of promoting good health and well-being to all residents. While this is laudable, paucity of reliable epidemiological data for different regions on diabetes and treatment outcomes may further widen the inequalities of access and quality of healthcare services across the country. This study examines the sociodemographic and clinical determinants of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in individuals attending primary healthcare in OR Tambo district, South Africa.

Design

A cross-sectional analytical study.

Setting

Primary healthcare setting in OR Tambo district, South Africa.

Participants

Patients treated for T2DM for 1 or more years (n=327).

Primary outcome measure

Prevalence of uncontrolled T2DM.

Secondary outcome measure

Determinants of uncontrolled T2DM (glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥7%).

Results

Out of the 327 participants, 274 had HbA1c≥7% (83.8%). Female sex (95% CI 1.3 to 4.2), overweight/obesity (95% CI 1.9 to 261.2), elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (95% CI 4.4 to 23.8), sedentary habits (95% CI 7.2 to 61.3), lower monthly income (95% CI 1.3 to 6.5), longer duration of T2DM (95% CI 4.4 to 294.2) and diabetes information from non-health workers (95% CI 1.4 to 7.0) were the significant determinants of uncontrolled T2DM. There was a significant positive correlation of uncontrolled T2DM with increasing duration of T2DM, estimated glomerular filtration rate and body mass index. However, a significant negative correlation exists between monthly income and increasing HbA1c.

Conclusions

We found a significantly high prevalence (83.8%) of uncontrolled T2DM among the patients, possibly attributable to overweight/obesity, sedentary living, lower income and lack of information on diabetes. Addressing these determinants will require re-engineering of primary healthcare in the district.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Primary healthcare study on glycaemic control in individuals treated for diabetes in a predominantly rural South African setting.

Epidemiological data on patients and health system determinants of glycaemic control were explored.

Owing to the cross-sectional design, the causal relationship with the determinants could not be ascertained.

We were cautious with overgeneralisation of the findings, due to the convenience sampling of participants and under-representation of men in the study.

Introduction

South Africa has pledged to the sustainable development goal of promoting good health and well-being to all residents. While this is laudable, paucity of reliable epidemiological data for different regions on diabetes and treatment outcomes may further widen the inequalities of access and quality of healthcare services across the country. Diabetes, an incurable chronic non-communicable disease, imposes a significant burden on the health services and has become a global public health problem.1 2 Although diabetes was considered the disease of the affluent, however, a paradoxical shift in rural–urban lifestyles means that populations from low socioeconomic communities too are affected.3–5

According to the International Diabetes Federation6 estimates, 371 million individuals were living with diabetes worldwide in 2012, accounting for a prevalence rate of 8.3%. The prevalence of diabetes ranges from 4.3% in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA; lowest), 6.7% in Europe, 10.5% in North America and the Caribbean to 10.9% in the Middle East and North Africa (highest).7 About 2 million people are living with diabetes mellitus (DM) in South Africa alone.1 It is, however, projected that the number of individuals with diabetes will double in SSA over the next 20 years (110% absolute increase by 2035),6 due to rapid nutritional and epidemiological transitions in the rural and urban communities.8 9 Going by the report of the International Diabetes Federation,7 SSA is ill prepared to deal with the astronomical increase in prevalence and incidence of diabetes and its complications in affected individuals.

Despite the scientific discoveries in diagnostic and treatment modalities, it appears that treatment outcomes of individuals with confirmed diabetes are generally suboptimal in SSA. The prevalence of uncontrolled diabetes ranges from 62% in Nigeria,10 66.7% in South Africa1 to 79.2% in Uganda11 and 82% in Botswana.12 These figures are in agreement with the findings of Diabcare study which reported good glycaemic control in only 29% of treated individuals in six African countries.13

Several reasons have been advanced for the suboptimal glycaemic control of diabetes in SSA. Lack of an operational diabetes programme, inefficient healthcare systems, inadequate staffing, stock-out of essential drugs and lack of patient empowerment14 15 were highlighted as reasons for suboptimal treatment outcomes documented in the majority of African countries. Likewise, the high level of unemployment, poor access to health facilities, lack of knowledge about diseases, perceptions and practices, poor attendance and failure to keep appointments at diabetes clinics could have impacted the poor health outcomes in Africa.16

In addition, the total health expenditure for diabetes in Africa (<1% of the total global health expenditure allocated for diabetes) is inadequate to cope with the health demand of diabetes,17 hence the poor treatment outcomes. There seems to be consensus among scholars that patient-related factors,4 5 18–22 disease-related factors and health system factors5 23 24 are the major determinants of poor glycaemic control. However, variation of factors influencing uncontrolled diabetes exists across regions and health facilities.4

In order for the South African Government to meet the sustainable development goal of promoting good health and well-being for all residents, data on the prevalence, treatment and glycaemic control of diabetes in rural and urban communities are needed for strategic planning on quality health service delivery. These epidemiological data are not available for OR Tambo district, an underserved region of South Africa. This study therefore bridges this gap by estimating the prevalence of uncontrolled diabetes, as well as identifying its sociodemographic and clinical determinants in individuals attending care in rural and semiurban communities of OR Tambo district, South Africa.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study drew participants from over 15 community health centres (primary care centres) in OR Tambo district, South Africa, to Mthatha General Hospital between June and November 2013. This district (level 1) hospital is located in a semiurban area and provides supervision for the referring community health centres in the rural communities surrounding Mthatha. Patients often receive diagnosis and treatment at Mthatha General Hospital with follow-up care at the nearest rural clinics where outreach clinicians provide monthly reviews.

Sample size

About two-thirds of individuals with diabetes were not achieving glycaemic control in South Africa.1 Erasmus et al25 also reported a 79.9% prevalence of uncontrolled diabetes in the study setting in the past decade. Daramola et al26 reported a prevalence of 71% in a primary healthcare setting in Western Cape, though in a different province and periurban setting. The sample size was estimated with the formula for a cross-sectional study:

Using the formula;

|

Z1−α=Z0.95=1.96, P=precision to an acceptable approximation of the study population at 95% CI, P is the proportion of patients with uncontrolled type 2 DM (T2DM). P is therefore taken to be 70% in order to achieve the maximum sample size. D is the absolute precision, and is taken as 0.05. The total sample size (n=323) was adjusted by a factor of 10% in anticipation of incomplete medical data.

Using the formula27 1÷(1−adjusted factor) multiply by the estimated sample size.

A total of 360 participants were included in the study.

Participants and inclusion criteria

Participants were invited from community health centres to attend the outpatient clinic at Mthatha General Hospital during the study period. They were included if age ≥30 years at diagnosis of DM and they had been on treatment for at least 1 year prior to the study. Exclusion criteria include type 1 diabetes, recent diagnosis of diabetes (<1 year), acutely ill and debilitated patients. A consecutive sample of 360 participants participated in the study.

Study instrument and pilot study

A structured questionnaire was designed in accordance with the main objectives of the study. A pilot study was conducted with 20 individuals living with diabetes who were excluded in the main study, at the Mthatha General Hospital, following which adjustments were made to the study instrument.

The Chief Executive Officer of the hospital granted permission for the study. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Data collection procedure

Data were recorded by personal interview and abstraction from medical files. The following independent variables were obtained from an investigator-aided interview: sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, marital status, type of residence, and monthly income, level of education and employment status) and lifestyle habits (smoking, excessive alcohol consumption and physical activity). Type of residence was categorised as semiurban (if participants resided in Mthatha) or rural (if participants resided in the neighbouring communities outside Mthatha). Smoking history was categorised as current smoker (smoked at least one cigarette within the past month), never-smoker and former smoker (having quit smoking more than 1 month prior to the study). Participants' consumption of alcohol was categorised as never drink, quit drinking (having quit drinking for more than one month prior to the study) and currently drinking (drank at least one unit of alcohol within the past month).1

Physical activity assessment focused on activities during work and leisure times in accordance with the Society of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes of South Africa;1 light to moderate activities without increase in respiratory frequency and heart rhythm (self-reported sedentary behaviour). Also, duration of diabetes and current medications was abstracted from the medical files. Duration of diabetes was defined as interval of diagnosis till the period of study. Other information obtained included sources of diabetes information, prior hospitalisation for hypoglycaemic episodes, self-reported adherence to medications and dietary contents. Evidence of diabetes complications: stroke (evident on clinical examination and prior documentation in the medical record), heart failure and renal failure (prior assessment documented in the medical record of the participants).

Measurements

Body weight in light clothes was measured to the nearest 0.5 kg in the standing position using a Soehnle Scale (Soehnle-Waagen Gmbh Co, Muurhardt, Germany) and height was measured by a stadiometer in standing position with closed feet (without shoes to the nearest 0.5 cm), holding their breath in full inspiration and Frankfurt line of vision.28 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated for each participant. BMI was categorised in accordance with the WHO criteria (2000) as <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.5–29.9 and >30.0 kg/m2 as underweight, normal, overweight and obese, respectively.

Blood pressures (systolic and diastolic) were measured in accordance with standard protocols29 with a validated Microlife BP A100 Plus model. Fasting venous blood (after an 8 or more hours overnight fast) was obtained for lipid profile, which includes total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglycerides (TGs). Creatinine level was assayed from the blood sample and the glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation. The dependent (outcome) variable is the glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level, which was performed in accordance with the international reference values and quality assurance criteria using stringent laboratory assays.1 Glycaemic control was categorised as: good (HbA1c≤7%), poor control (HbA1c>7%), moderately poor (HbA1c=7–8.9%) and critically poor (HbA1c≥9%).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean values±SDs for continuous variables. Counts (frequency=n) and proportions (%) were reported for categorical variables. Percentages were compared using χ2 test. Student's t-test was used to compare means between groups. Univariate OR using Mantel-Haenszel and multivariate OR using logistic regression analysis were calculated with their 95% CIs to define any association between uncontrolled T2DM (dependent variable) and its associated factors (independent variables). The logistic regression model was also adjusted for confounding factors. A p<0.05 was considered for significant difference. Data were analysed by Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) V.21 for windows (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Out of the 360 recruited, 33 had incomplete data (blood results and medical information). Total participants included in the analysis were 327. Table 1 describes the study participants according to the sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Females | 230 | 70.3 |

| Males | 97 | 29.7 |

| Educational level | ||

| Tertiary | 19 | 5.8 |

| Secondary (grade 7–12) | 196 | 60.9 |

| Primary (grade 1–6) | 67 | 20.5 |

| Illiterate (no formal education) | 45 | 13.8 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 290 | 88.7 |

| Semiurban | 37 | 11.3 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus duration (years) | ||

| ≥3 | 195 | 59.6 |

| 1–3 | 132 | 40.9 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smoked | 252 | 77.1 |

| Former smoker | 60 | 18.3 |

| Current smoker | 15 | 4.6 |

| Alcohol consumption status | ||

| Never drank | 233 | 71.3 |

| Quit drinking | 71 | 21.7 |

| Currently drinking | 23 | 7 |

N, number of participants; %, percentage of total number of participants.

The majority of participants were females (70.3%), lived in rural communities (88.7%), achieved at least secondary education (67%), never drank alcoholic beverages (71.3%) and never smoked cigarettes (77.1%). All participants consumed the prevalent diet: pap, porridge, meat, rice, bread and fast food items (all energy-dense foods).

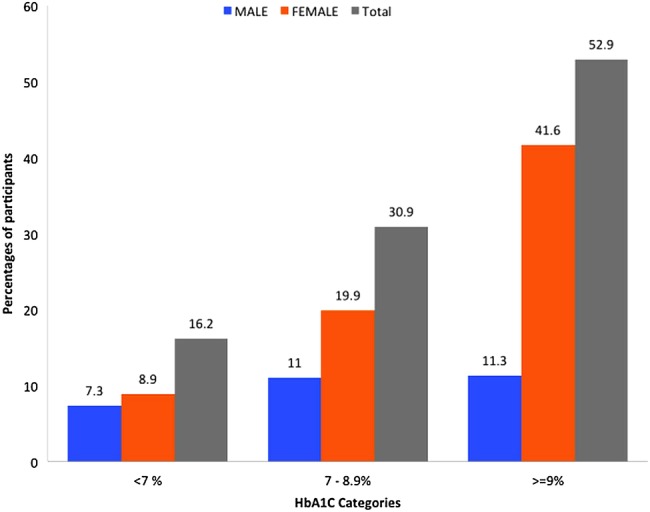

Some participants had suffered diabetes complications: stroke (n=11), renal failure (n=80) and heart failure (n=7). Prevalence of uncontrolled T2DM was 83.8% in the studied population: male 75.3% (n=73/97) and women 87.4% (n=201/230). Figure 1 describes the glycaemic control according to sex distribution and categories of HbA1c level.

Figure 1.

Glycaemic control according to sex distribution. HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin.

In univariate analysis, there was a significantly higher risk of poor glycaemic control among individuals with longer duration of T2DM, obesity, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), higher TG levels and, paradoxically, elevated HDL-C (table 2).

Table 2.

Determinants of uncontrolled T2DM: univariate analysis

| Uncontrolled T2DM | Controlled T2DM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | p Value |

| Age (Years) | 58.5±12.7 | 59.8±12.0 | 0.508 |

| Monthly income (Rand) | 1855.80±159.90 | 2752.70±492.80 | 0.350 |

| T2DM duration (years) | 7.1±6.1 | 3.4±2.9 | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.1±5.4 | 29.4±3.7 | <0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 151.4±30.7 | 148.4±31.6 | 0.522 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 81.1±14.2 | 80.2±13.6 | 0.652 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.7±3.1 | 4.0±1.2 | 0.144 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.2±0.4 | 1.0±0.4 | 0.047 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 2.1±1.3 | 2.0±2.1 | 0.047 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 47.9±19.8 | 93.6±22.5 | 0.045 |

BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Furthermore, the risk of poor glycaemic control was higher among those on a combination therapy of insulin and metformin (91.2%, n=83/91, OR=2.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 5.4; p=0.024). Also, a higher risk of poor glycaemic control was found among patients on insulin (91.7%, n=88/96, OR=2.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 5.9; p=0.013) in comparison with those without insulin. The majority (97.5%, n=315/323) of participants reported poor adherence with treatment.

The risk of uncontrolled diabetes was lower among individuals with prior hypoglycaemic episodes (68.4%, n=26/38, OR=0.4, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.8; p=0.006). Significant positive associations were observed between elevated levels of HbA1c (uncontrolled T2DM) and BMI, T2DM duration, LDL-C and eGFR levels. However, a paradoxical association was found between elevated levels of HbA1c and monthly income (table 3).

Table 3.

Significant associations of uncontrolled T2DM and independent determinants

| HbA1c<7% | HbA1c=7–8.9% | HbA1c≥9% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | p Value |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4±3.7 | 32.7±5.2 | 32.0±5.0 | <0.0001 |

| Monthly income (Rand) | 1769.80±1311.00 | 1269.30±420.30 | 1054.20±938.50 | <0.0001 |

| T2DM duration (years) | 3.4±2.9 | 6.5±5.9 | 7.5±6.3 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.3±1.9 | 4.2±1.4 | 3.8±1.6 | 0.002 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 93.6±22.5 | 50.4±26.4 | 43.5±29.2 | 0.027 |

BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The final model of the multivariate logistic regression (LR) method shows that the significant determinants of uncontrolled T2DM were longer duration of T2DM, overweight/obesity, female gender, sedentary lifestyles, higher LDL-C, lower monthly income and source of diabetes information from non-health workers after adjusting for other variables (residence, monthly income, alcohol intake, smoking status, medications, previous hypoglycaemic episodes, HDL-C and eGFR; table 4).

Table 4.

Significant determinants of uncontrolled T2DM: multivariate analysis

| Variables | β | SE | Wald | OR (95%CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2DM duration (years) | |||||

| ≥9 | 3.578 | 1.075 | 11.084 | 35.8 (4.4 to 294.2) | <0.001 |

| <9 | Reference 1 | ||||

| Overweight/obesity | |||||

| Yes | 3.103 | 1.256 | 6.099 | 22.3 (1.9 to 261.2) | 0.014 |

| No | Reference 1 | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Females | 1.230 | 0.416 | 8.767 | 3.4 (1.5 to 7.7) | 0.003 |

| Males | Reference 1 | ||||

| Sedentary lifestyle | |||||

| Yes | 3.044 | 0.547 | 31.027 | 21 (7.2 to 61.3) | <0.0001 |

| No | Reference 1 | ||||

| LDL-C≥2.2 (mmol/L) | |||||

| Yes | 2.331 | 0.429 | 29.579 | 10.3 (4.4 to 23.8) | <0.0001 |

| No | Reference 1 | ||||

| Monthly income | |||||

| <R1200 | 1.046 | 0.420 | 6.215 | 2.9 (1.3 to 6.5) | 0.013 |

| ≥R1200 | Reference 1 | ||||

| Source of DM information | |||||

| Non-health workers | 1.153 | 0.407 | 8.008 | 3.2 (1.4 to 7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Health workers | Reference 1 | ||||

| Constant | −4.710 | 1.345 | 12.258 | <0.0001 | |

DM, diabetes mellitus; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

This study sought to determine the prevalence of uncontrolled T2DM and its sociodemographic and clinical determinants among individuals attending primary healthcare in OR Tambo district, South Africa. We found a significantly high prevalence (83.8%) of uncontrolled T2DM in the study population. This prevalence is slightly higher than the previously reported prevalence of 79.9% more than a decade from the same setting.22 The rate of uncontrolled T2DM from this study is higher than the rates from a similar level of care in Western Cape Province (71%)26 and Northwest Province (69.3%),30 respectively, within South Africa. However, it is comparable with another South African report from KwaZulu-Natal Province (83%) reported by Igbojiaku et al.31 Poor glycaemic control has been documented in different parts of Africa: Congo DRC32 (68%), Nigeria10 (62%), Uganda11 (79.2%) and Botswana12 (82%). There seems to be a trend of poor glycaemic control among the indigenous Africans irrespective of their location, which portends danger for their health.

It should be noted that the influence of nutritional transitions, changing lifestyles and decline in health system performance in the past decade might contribute to variations comparable to those found in this study. Nevertheless, the high prevalence rate of uncontrolled T2DM observed in our sample is worrisome, given the deleterious health implications of uncontrolled T2DM. Several underlying issues may contribute to uncontrolled diabetes among the population studied. It might be possible that many patients do not truly understand the health implications of having uncontrolled T2DM. However, this supposition is only speculative. Therefore, a study examining the perception and knowledge of patients attending healthcare centres concerning uncontrolled T2DM is imperative.

It should be noted that predominantly rural communities in South Africa and the rest of Africa are faced with the similar problem of poor access to quality healthcare services.15 Patients travel long distances to townships for hospital visits; they are largely poor, unemployed and live in rural communities. The rural communities lack functional health facilities; there is a regular stock-out of medications and lack of doctors and nurses. Further access to quality healthcare becomes unattainable due to poverty.32 33 The relationship of poverty and health indicators cannot be ignored in these rural communities. Significant patient-related factors: female gender, rural residence, obesity, unemployment, poor monthly income and diabetes information from non-healthcare workers were associated with uncontrolled T2DM in our study. There was a high representation of women (70.3%) among the study participants, which reflects the overall higher level of usage of health facilities by women in South Africa.34 Although the association of poor glycaemic control had been documented in the literature,4 20 it is likely that fewer men (29.7%) in this study were using their medication and following dietary advice. Therefore, a population-based study in these communities would help determine the true prevalence of uncontrolled T2DM among men in the region.

The majority of participants were unemployed (89.2%) and had a monthly income of <R1200 (<US$100), which suggests the glaring level of poverty in this region. This impacts directly on the health-seeking behaviour of patients, such as cost of transportation to hospitals for routine check-up and pick up of medications, money for glucometer and other basic needs. These social determinants of health were reported in SSA previously.15 16 Also, poverty impacts on the food contents of the participants, which are limited to energy-dense food and thus could contribute to poor glycaemic control. The current study found no association between the age of patients and level of glycaemic control. However, this finding is in contrast to the systematic review by Sanal et al4 which reported a strong association between increasing age and good glycaemic control. Obesity is an independent determinant of uncontrolled diabetes in this study. Many other studies have reported a similar association between obesity and uncontrolled diabetes.19–21

Despite the fact that a high proportion (66.7%) of the study participants achieved at least secondary education, the level of education was not statistically significant (p>0.05) in this study. Ismail et al22 had reported no relationship between level of education and level of glycaemic control among patients with T2DM. Physical inactivity was an independent and significant determinant (p<0.0001) of uncontrolled T2DM in the study. The benefits of exercise in reducing cardiovascular risks have been documented.35 36 Aerobic exercises improve insulin sensitivity and metabolic control. However, the rural residence and age of participants may explain why formal exercises might be unattainable; hence, aerobic exercise should be appropriate for age, gender and social environment of each patient.

Diabetes information from non-healthcare workers is an independent determinant of uncontrolled diabetes in this study. Sources of diabetes education are crucial for gaining relevant lifestyle changes required to improve glycaemic control. It is observed that the majority of participants reported poor compliance with treatment. Patient education is crucial to improve compliance with medications. Education provided by a trained diabetes educator is more significant for good glycaemic control.21 37 Inadequate staffing with doctors and nurses and lack of diabetes educators in the local health facilities are some of the reasons for the poor treatment outcomes in our setting. Patients' education on their clinical condition therefore comes from unverified sources.

The paradoxical association of uncontrolled T2DM and insulin therapy in the study warrants further investigation. Further clarity on the suboptimal glycaemic control in participants on insulin therapy could not be ascertained due to lack of data on the timing of initiation and dosing schedule of insulin therapy in the participants. Nevertheless, the possibility of clinic inertia such as delays in initiating insulin therapy, failure of optimisation of insulin doses and inadequate follow-up of patients cannot be ignored as the reasons for our results. Early initiation of insulin within 3 years of diagnosis of diabetes would preserve the β-cells of the pancreas.35 In addition to clinic inertia, access to clinic follow-up for optimisation of insulin doses may probably be unattainable due to costs of transport to hospital as a result of poverty.

Also, our study reported a significant association between uncontrolled diabetes and longer duration of diabetes. Individuals with diabetes for at least 9 years have higher odds of having poor glycaemic control (OR=35.8). Long duration of chronic hyperglycaemia is associated with β-cell loss and further deterioration of glucose homoeostasis.35 Chronic hyperglycaemia is a precursor to diabetes nephropathy and thus further deterioration in glucose metabolism.35 Also, a significant association (p=0.002) was observed between uncontrolled diabetes and LDL-C, with elevated levels in participants with HbA1c≥9.0%. The risk of uncontrolled T2DM was higher (twofold) in participants with LDL-C≥2.2 mmol/L. Chronic intracellular lipids in the liver are associated with deterioration in the functions of β-cells and development of non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis.35 The paradoxical increase in HDL-C in individuals with uncontrolled T2DM warrants further investigation.

Association of LDL-L, renal failure and long duration of diabetes with uncontrolled diabetes has been reported previously.4 5 19 There was a positive linear association between uncontrolled diabetes and declining GFR level; participants with HbA1c≥9.0% were more likely to have renal impairment. This has clinical implications for management of patients. Metformin (biguanide), one of the commonly used oral hypoglycaemic drugs, is associated with lactic acidosis in the presence of renal failure.35 Therefore, clinicians need to regularly monitor the renal functions. It should also be noted that some participants had already developed complications: stroke, heart failure and renal failure. This is, however, not surprising, based on the high prevalence of uncontrolled T2DM.

Limitations

The inherent limitations of a cross-sectional study cannot be ignored. Indeed, only prospective studies might demonstrate a causal association between the determinants and uncontrolled T2DM. Besides, the self-reporting of participants could not rule out the possibility of bias in the participants' responses, such as under-reporting of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption. Also, the under-representation of men did not allow for a good understanding of glycaemic control in our studied population. The convenience sampling of participants coupled with a health facility-based study may have introduced bias. Besides, the glycaemic control in this study may have underestimated the true prevalence at the population level in the communities.

Notwithstanding the limitations, the study provides epidemiological data on glycaemic control of diabetes in an understudied region with poor access to quality healthcare services. The findings might help inform future healthcare decisions on resource allocations (human and material) with a priority for improvement in diabetes care services in the underserved communities.

Conclusion

This study indicates that uncontrolled T2DM is high among the rural, poor socioeconomic communities of OR Tambo district, South Africa. This is worrisome, given the health implications of uncontrolled T2DM. Also, obesity, longer duration of T2DM, poverty, lack of diabetes education, sedentary lifestyle and dyslipidaemia are identified as the most important and independent determinants of T2DM in the setting. Clinicians should pay attention to the determinants of uncontrolled diabetes and overcome their inertia to initiate and optimise insulin therapy in the management of individuals living with diabetes. There is an urgent need for re-engineering of primary healthcare with prioritisation of diabetes care and other non-communicable diseases in the rural underserved communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of Mthatha General Hospital for their involvement in the successful completion of the research work.

Footnotes

Contributors: OVA and PY conceived and designed the study protocol, coordinated the data collection and drafted the manuscript. BL-M and AIA participated in the study design and performed the statistical analyses. DTG participated in data collection and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained in accordance with the Helsinki II Declaration from the Walter Sisulu University Ethical Committee and Eastern Cape Department of Health, South Africa.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Amod A, Ascott-Evans BH, Berg GI et al. . The 2012 SEMDSA guideline for the management of type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol Metab Diabetes S Afr 2012;17:61–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmet P. The burden of type 2 diabetes: are we doing enough? Diabetes Metab 2003;29:6S9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB et al. . Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012;35:1364–79. 10.2337/dc12-0413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanal T, Nair N, Adhikari P. Factors associated with poor control of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetol 2011;3:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khattab M, Khader YS, Al-Khawaldeh A et al. . Factors associated with poor glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat 2010;24:84–9. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atlas ID. Homepage en Internet. update 2012. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 12 Nov 2015).

- 7.International Diabetes Federation. The IDF diabetes atlas. 6th edn Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2013. http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/EN_6E_Atlas_FULL_0.pdf (accessed on 14 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandala NB, Stranges S. Geographic variation of overweight and obesity among women in Nigeria: a case for nutritional transition in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e101103 10.1371/journal.pone.0101103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill GV, Mbanya JC, Ramaiya KL et al. . A sub-Saharan African perspective of diabetes. Diabetologia 2009;52:8–16. 10.1007/s00125-008-1167-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngwogu K, Mba I, Ngwogu A. Glycaemic control amongst diabetic mellitus patients in Umuahia Metroppolis, Abia State, Nigeria. Int J Basic Appl Innovative Res 2014;1:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kibirige D, Atuhe D, Sebunya R et al. . Suboptimal glycaemic and blood pressure control and screening for diabetic complications in adult ambulatory diabetic patients in Uganda: a retrospective study from a developing country. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2014;13:40 10.1186/2251-6581-13-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mengesha A. Blood glucose as a predictor of glycaemic control by glycosylated haemoglobin in Gaborone, Botswana. Diabetes 2007;15:15.–. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobngwi E, Ndour-Mbaye M, Boateng KA et al. . Type 2 diabetes control and complications in specialised diabetes care centres of six sub-Saharan African countries: the Diabcare Africa study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012;95:30–6. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kengne AP, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Sobngwi E et al. . New insights on diabetes mellitus and obesity in Africa–part 1: prevalence, pathogenesis and comorbidities. Heart 2013;99:979–83. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beran D, Yudkin JS. Diabetes care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2006;368:1689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall V, Thomsen RW, Henriksen O et al. . Diabetes in Sub Saharan Africa 1999–2011: epidemiology and public health implications. A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011;11:564 10.1186/1471-2458-11-564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peer N, Kengne AP, Motala AA et al. . Diabetes in the Africa Region: an update. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:197–205. 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagrebetsky A, Griffin S, Kinmonth AL et al. . Predictors of suboptimal glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes patients: the role of medication adherence and body mass index in the relationship between glycaemia and age. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012;96:119–28. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teoh H, Braga MF, Casanova A et al. . Patient age, ethnicity, medical history, and risk factor profile, but not drug insurance coverage, predict successful attainment of glycemic targets: Time 2 Do More Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (T2DM QUERI). Diabetes Care 2010;33:2558–60. 10.2337/dc10-0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adham M, Froelicher ES, Batieha A et al. . Glycaemic control and its associated factors in type 2 diabetic patients in Amman, Jordan. East Mediterr Health J 2010;16:732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan JC, Gagliardino JJ, Baik SH et al. . Multifaceted determinants for achieving glycemic control the International Diabetes Management Practice Study (IDMPS). Diabetes Care 2009;32:227–33. 10.2337/dc08-0435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ismail IS, Nazaimoon WM, Mohamad WB et al. . Socioedemographic determinants of glycaemic control in young diabetic patients in peninsular Malaysia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2000;47:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawada T, Otsuka T, Inagaki H et al. . Optimal cut-off levels of body mass index and waist circumference in relation to each component of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and the number of MetS component. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2011;5:25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khunti K. Use of multiple methods to determine factors affecting quality of care of patients with diabetes. Fam Pract 1999;16:489–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erasmus RT, Blanco E, Okesina AB et al. . Assessment of glycaemic control in stable type 2 black South African diabetics attending a peri-urban clinic. Postgrad Med J 1999;75:603–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daramola OF. Assessing the validity of random blood glucose testing for monitoring glycemic control and predicting HbA1c values in type 2 diabetics at Karl Bremer hospital. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS et al. . Designing clinical research. 3rd edn: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Committee WE. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seedat Y, Rayner B, Veriava Y. South African hypertension practice guideline 2014: erratum. Cardiovasc J Afr 2015;26:90–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tumbo JM, Kadima FN. Screening of long-term complications and glycaemic control of patients with diabetes attending Rustenburg Provincial Hospital in North West Province, South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2013;5:5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Igbojiaku OJ, Harbor OC, Ross A. Compliance with diabetes guidelines at a regional hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2013;5:5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Longo-Mbenza B, Mvindu HN, On'kin JBK et al. . The deleterious effects of physical inactivity on elements of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in Central Africans at high cardiovascular risk. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2011;5:1–6. 10.1016/j.dsx.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adeniyi OV, Longo-Mbenza B, Goon D. Female sex, poverty and globalization as determinants of obesity among rural South African type 2 diabetics: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:298 10.1186/s12889-015-1622-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nteta TP, Mokgatle-Nthabu M, Oguntibeju OO. Utilization of the primary health care services in the Tshwane Region of Gauteng Province, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2010;5: e13909 10.1371/journal.pone.0013909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar P. Kumar & Clark's Clinical Medicine. International Edition ed 2009.

- 36.Longo-Mbenza B, Muaka M, Mbenza G et al. . Risk factors of poor control of HBA1c and diabetic retinopathy: paradox with insulin therapy and high values of HDL in African diabetic patients. Int J Diabetes Metab 2008;16:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riveline JP, Schaepelynck P, Chaillous L et al. . Assessment of patient-led or physician-driven continuous glucose monitoring in patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes using basal-bolus insulin regimens A 1-year multicenter study. Diabetes Care 2012;35:965–71. 10.2337/dc11-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]