Abstract

Strengths-based solution-focused approaches are gaining ground in statutory child protection work, but few studies have asked front line practitioners how they navigate the complex worker–client relationships such approaches require. This paper describes one component of a mixed-methods study in a large Canadian statutory child protection agency in which 225 workers described how they applied the ideas of strengths-based practice in their daily work. Interviews with twenty-four practitioners were analysed using an interpretive description approach. Only four interviewees appeared to successfully enact a version of strengths-based practice that closely mirrored those described by key strengths-based child protection theorists and was fully congruent with their mandated role. They described navigating a shifting balance of collaboration and authority in worker–client relationships based on transparency, impartial judgement, attentiveness to the worker–client interaction and the value that clients were fellow human beings. Their accounts extend current conceptualisations of the worker–client relationship in strengths-based child protection work and are congruent with current understandings of effective mandated relationships. They provide what may be a useful model to help workers understand and navigate relationships in which they must reconcile their own authority and expertise with genuine support for the authority and expertise of their clients.

Keywords: Child welfare, child protection, strengths-based, solution-focused, worker–client relationship

Introduction

Over the last decade, a number of strengths-based solution-focused approaches have been developed for child protection settings. These emphasise the relationship between child protection workers and their clients as ‘the principle vehicle for change’ (Turnell and Edwards, 1999, p. 47). Yet these relationships are complex, requiring workers to actively pursue the clients' perspectives, strategies and goals while exercising their mandated authority when negotiated solutions fall short of ensuring child safety. While the focus of published work has been on describing the content, implementation and outcomes of strengths-based child protection approaches, this article offers some insight into what front line workers in a large Canadian child protection agency perceived strengths-based practice to mean for worker–client relationships. It focuses on the workers who appeared most successful in applying strengths-based practice and describes how they interpreted the approach.

The question of how to navigate strengths-based relationships from a position of authority becomes important as strengths-based approaches gain popularity in child protection work. The most prevalent, the Signs of Safety® (Turnell, 2012; Turnell and Edwards, 1999), has been implemented in 50–100 jurisdictions across Europe, North America and Australia (Bunn, 2013; Turnell, 2012). Thirty-nine English local authorities are using, considering using or have staff trained to use the approach (Bunn, 2013). Another well-researched strengths-based child protection approach, Solution-Based Casework, has been implemented in five American states (Antle et al., 2012). Studies suggest these approaches are popular with clients (Skrypek et al., 2012) and practitioners (Antle et al., 2008; Department for Child Protection, 2010; Wheeler and Hogg, 2012), and are linked to a range of good outcomes including reduced recidivism and rates of admissions to care (Antle et al., 2008, 2012; Idzelis Rothe et al., 2013).

The growing interest in strengths-based child protection practice makes it important to listen to the experiences of front line workers charged with enacting the approach. This article describes findings from interviews with twenty-four such practitioners in a large Canadian statutory child protection agency which introduced strengths-based practice in 2003 and by 2008 expected all child protection workers to use the approach. Most practitioners described struggling to reconcile the approach with the exercise of their mandated authority and talked of it being only sometimes applicable to their work. However, four interviewees saw it as relevant and possible in all situations. Their descriptions of the approach were very similar to those of authors like Berg and Kelly (2000) and Turnell and Edwards (1999), who have been most influential in the development of strengths-based child protection practice. They extend current conceptualisations of the strengths-based worker–client relationship in protection settings, providing a possible model for how to make such complicated relationships work.

Strengths-based practice in child protection

The original iteration of strengths-based social work was developed at the University of Kansas in the late 1980s as a mental health case management approach. It required workers to systematically identify client perspectives, goals and strengths, and pursue client-directed plans for successful community living (Rapp and Lane, 2012, p. 150). Saleebey (1992) later reframed it as a general social work perspective, now commonly called the strengths approach, which required the worker to address client challenges by eliciting, emphasising and working with their strengths and goals. This perspective is commonly seen as operationalised (Rapp et al., 2006) through practice models like solution-focused therapy (De Shazer, 1985).

Strengths-based approaches were first developed for child protection settings at the end of the 1990s. They drew heavily on the principles and strategies of solution-focused therapy and maintained an explicit focus on the goal of child safety (Berg and Kelly, 2000; Turnell and Edwards, 1999). Common principles of strengths-based child protection approaches are:

The adult client is a respected partner in creating safety for the child.

Every family has strengths on which the solutions to child welfare problems can be built.

The goal of the work is the future safety of the child and this requires assessment of risk.

The work is driven by the motivation of clients to achieve their own goals.

The worker and client together co-construct solutions and motivation through relationship and language.

Coercion and partnership are not mutually exclusive.

The worker strategically uses the tools of solution-focused therapy.

Such approaches require the worker to step out of the expert role to adopt a ‘non-knowing posture’ and communicate ‘genuine awe and respect’ (Berg and Kelly, 2000, p. 98) for the client's perspective. To maximise the therapeutic potential to work through the client's interpretations, the worker holds her own in abeyance for as long as possible. Workers have to ‘hold at least five different stories in their head at one time’ (Turnell and Essex, 2006, p. 38) and remain open to changing their judgements in the belief that all knowledge is incomplete. Clients are perceived to have considerable powers of self-determination and the worker is required to respect their right to make informed decisions:

In interviews we discipline ourselves to ask questions with no investment in client outcomes. This posture does not represent an uncaring attitude toward clients or the welfare of the community but an acceptance of the reality that we are working with human beings who make choices (De Jong and Berg, 2001, p. 372).

There is more to this relationship, however, than supporting client self-determination. This is a purposeful goal-centred relationship in which the worker exercises considerable power to structure and direct the work. The child protection worker guides client interviews with structured and persistent communication and therapeutic techniques, hypothesises future goals before he and the client meet, and uses the client's goals as leverage for co-operation (Turnell and Edwards, 1999). As Berg and Kelly (2000) explain, ‘What we can do is to influence clients in such a way that they believe it is in their desire and in their best interest to change. This is all done with talking’ (p. 80).

Strengths-based child protection workers must gather information, assess risk and exercise their authority when necessary. Attentive listening and encouragement for client self-determination are combined with clarity about the child protection concerns and honesty about mandated authority (Turnell and Edwards, 1999). The worker is explicit about what is and is not negotiable and straightforward about consequences and expectations. This position demands continual movement between expressing empathy and establishing expectations of the client as the worker navigates a relationship of mutuality in which there is sufficient separation to ensure decisions are made in the best interests of the child.

The relationship relies as much on the worker's warmth and spontaneity as her skills in working with the client's position. The client needs continual encouragement (Antle et al., 2012) and workers are advised to ‘maintain humour, hope and gratitude. Do not take yourself too seriously’ (Berg and Kelly, 2000, p. 73). Turnell et al. (2008) write of a social worker who, when confronted by a one-eared father screaming at her to ‘f*** off’, asks when she can ‘f*** back’ and adds ‘I couldn't help notice the fact that you hardly have a left ear, and if you don't tell me how that happened I don't think I'll be able to concentrate on what we have to talk about’ (p. 105). Even while strategically guiding the relationship for therapeutic ends, the whole worker, not just the professional persona, is required to show up.

The challenges of negotiating relationships like this in contemporary child welfare organisations appear significant. The assumption of strengths-based approaches that ‘most people can change their behaviour when provided with support and adequate resources’ (Berg and Kelly, 2000, p. 63) may not translate well to contexts in which support and resources are scarce. For many workers, the neo-liberal restructuring of social welfare systems has meant less client contact as information management, risk management, service gate-keeping and accountability processes have been prioritised (Parton, 2008). High turnover means the front lines are manned disproportionately by inexperienced workers (Healy et al., 2009) who often experience stress (Boyas et al., 2012) and abuse (Ferguson, 2005; Harris and Leather, 2012), and rarely receive the support necessary for relational practice in a field characterised by pervasive anxiety (Ruch, 2007). Whether and how workers manage under such conditions to negotiate the complex relationships required by strengths-based practice was a driving question for this study.

Method

This article describes the interview stage of a pragmatic mixed-methods study which began with an online survey and was followed by in-depth interviews with child protection workers. Interpretive description (Thorne, 2008), an applied qualitative research methodology, guided the interview stage. As in this study, interpretive description research is grounded in an extensive review of knowledge in the relevant field of practice, employs multiple data collection methods and analytical perspectives, and uses inductive coding and constant comparative analysis techniques.

Following approval by university and agency ethics committees, 225 participants were recruited through emails sent to all 824 front line child protection workers employed by the agency to assess and respond to child protection concerns. From the seventy workers who volunteered to be interviewed, purposive sampling identified twenty-four participants representing maximum variation in age, self-reported experience using strengths-based practice and range of views as to the difficulty of the approach. All interviewees gave written and verbal consent to proceed.

Four participants chose to be interviewed in person and twenty by telephone. Interviews lasted an average of seventy-four minutes. Second interviews were held with two interviewees to complete data collection on all issues covered in the semi-structured interview guide. This guide focused inquiry on the ways in which interviewees defined and enacted strengths-based practice and the supports and barriers to that process. So as to elicit participant interpretations of the approach, strengths-based practice was not defined by the researchers. All interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Each participant was assigned a code number; participant quotations in this article are attributed using this number. Data collection ended when concurrent analysis produced a conceptual understanding of the issue that was well grounded in participants' experiences and threw new light on the practice issue being explored.

Data analysis

Detailed coding of the interview transcripts began with inductive labelling of each distinct idea in the text for both its overt meaning and the actions, meanings, supports and barriers linked to strengths-based practice. Some large categories were also created to group together common ideas like ‘supports’ and ‘challenges’ that were directly related to the research questions. Analysis proceeded through an iterative process of comparing and contrasting coded data pieces to each other and to the entire data set to analyse for similarities and differences. This enabled similar codes to be grouped into progressively larger and more conceptual categories and the initial broad categories to be broken into smaller ones with distinct properties. The result was five broad themes or definitions of strengths-based practice, each linked to particular supports and barriers. Member checks involved interviewees identifying and discussing by e-mail the definition that best fit the way they practised. Their responses were analysed as data.

Participants

The demographic characteristics of interviewees, arranged according to the definition of strengths-based practice to which they subscribed, are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interviewees by definitional group

| Age |

SBP experience (years) |

Child protection experience (years) |

Gender |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Female | Male | |

| Relating therapeutically (n = 3) | 32.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 2.33 | 1.53 | 2 | 1 |

| Supporting client self-determination (n = 7) | 38.43 | 9.64 | 9.86 | 9.86 | 10.43 | 7.00 | 6 | 1 |

| Connecting to internal and external resources (n = 6) | 38.83 | 3.87 | 7.83 | 4.17 | 4.67 | 3.88 | 6 | 0 |

| Pursuing a balanced understanding (n = 4) | 38.00 | 14.88 | 10.25 | 9.54 | 7.00 | 6.63 | 2 | 2 |

| Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice (n = 4) | 45.00 | 13.78 | 16.50 | 15.78 | 9.00 | 4.90 | 1 | 3 |

Findings

Five distinct versions of strengths-based practice were constructed from interviewee descriptions of how they applied the approach in their daily work (Oliver and Charles, 2015). These versions were characterised as ‘Supporting client self-determination’; ‘Relating therapeutically’; ‘Connecting to internal and external resources’; ‘Pursuing a balanced understanding’; and ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’. Their content and relative applicability to child protection work are described in detail elsewhere (Oliver and Charles, 2015). The lack of a shared definition was partly explained by the fact that the agency did not subscribe to a single strengths-based model, leaving workers exposed to a range of messages from their training and the social work literature about what strengths-based practice in child protection settings entailed.

Four of the five versions of the approach were deemed by interviewees to require parental collaboration. This made their inconsistent implementation an important strategy allowing workers to assert their mandated authority when child safety could not be secured through collaboration alone (Oliver and Charles, 2015). Only ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ reflected all core principles of strengths-based child protection approaches, including the principle that coercion and partnership are not mutually exclusive. It was the only version of strengths-based practice described as always applicable to child protection work. For these reasons, ‘Enacting firm fair and friendly practice’ is the focus of this article. Although described by only four interviewees, it illuminates one way workers might consistently implement strengths-based practice in statutory child welfare settings.

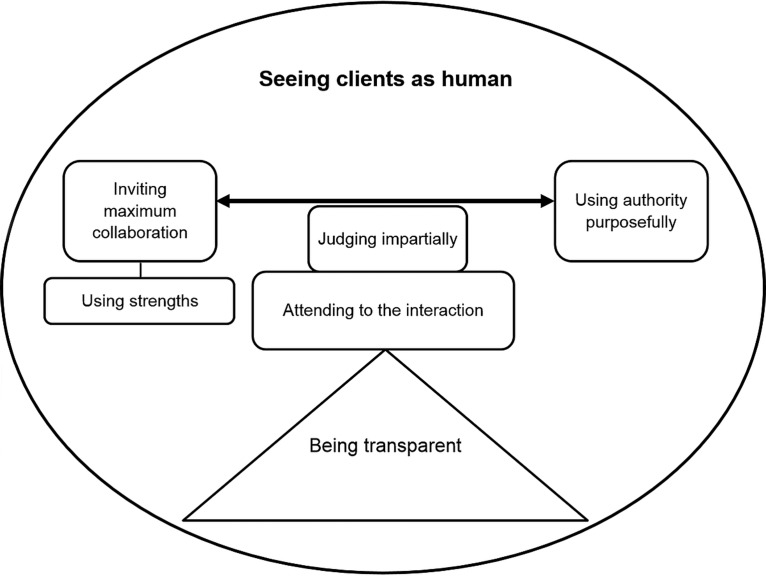

The average age and years of strengths-based practice for interviewees describing ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ were greater than for those describing the other versions. This is likely due to the fact that ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ requires a delicate balance of authority and collaboration that appears particularly challenging for inexperienced workers (Oliver, 2014). How to support practitioners to implement this approach is discussed in detail elsewhere (Oliver, 2014), but a first step is to articulate the approach's core components. These are illustrated in Figure 1 and described below.

Figure 1.

‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’

© Oliver, 2014.

Inviting maximum collaboration in the process

This version of strengths-based practice included inviting clients to engage in the child protection process to the maximum extent possible. This meant continually asking for, listening to and utilising client perspectives and goals. It meant inviting client feedback on the worker's intervention and being open to their criticism.

A key collaborative strategy was identifying client strengths, often with the aid of solution-focused questioning techniques. Complimenting strengths encouraged clients and increased motivation, self-esteem and agency:

I start to build on that strength, it brings a sense, you know, and I'll use a social-worky word, you know, it brings empowerment, right? And so people get this natural, you know, endorphin release like: wow gee, I can do good things, I can do this (Participant 102).

Strengths could also be used or ‘leveraged’ (254) in safety plans. Plans might ask clients to contribute to child safety in the areas in which they felt most competent or rely on protective people and resources in the broader family and community network.

The extent of possible collaboration changed over the course of the relationship, as it was intimately connected to the shifting nature of client engagement and worker authority. There was never a time, however, when meaningful collaboration was not possible. This was because workers adjusted their expectations for collaboration in accordance with the client's perceived capacity and engagement. Some clients quickly became full partners in safety planning, inviting participants to planning conferences and setting goals. For others, collaboration was built incrementally through participation in small decisions about process, like making choices as to how quickly the worker should return their calls. Workers moved from acknowledging their authority to attempting to reduce the power difference between themselves and clients. They did this by attempting to increase client power rather than denying their own and were clear that collaboration was ‘to the degree possible’ (254), within limits of their mandate, of client capacity and of their own need for safety. As one said:

What I notice is that the social worker's making efforts and, it's never gonna be equalised, but to create a safe environment where that person can feel a bit more equal and neutralising that power dynamic. Not erasing it, 'cos you can never take that away but giving the client a voice and acknowledging what they're saying and then, you know, doing their job respectfully (176).

Using authority purposefully

This version of strengths-based practice included the purposeful use of mandated authority. The ability to set and maintain clear boundaries was perceived to be an important element of a firm and fair worker–client relationship. It prevented clients from being taken by surprise by mandated requirements and made the strengths-based relationship one in which clients always knew where they stood. It supported the sense that this was a purposeful relationship in which clients could trust that workers would follow through on their clear commitments to child safety:

I'm there to praise and encourage and stuff like that, all the while I'm towing a very solid line, right? Like I mean, I'm not here to be your buddy, I'm not your friend at the door, you know, I am a child protection worker who's responding to a valid child protection concern, y'know? This is not a voluntary service this is an involuntary service and so I'm not there to be your bestie. I'm there to make sure that the children's needs are met (102).

Workers adjusted their level of directiveness to match client insight, capacity and engagement with the process. When clients were angry or reluctant to engage, workers needed to be persistent and exercise their authority even about the need for client contact. This was because strengths-based practice required genuine collaboration in which both parties were required to participate and it might take several meetings to develop the conditions for an honest and productive exchange. Being directive was, however, perceived to be a temporary stance. Workers immediately sought to offer clients choices that might re-engage them in a more collaborative process:

After trying to de-escalate things, keep things on a calm thoughtful level, there are still times when my assertive presence emerges. It's not aggressive, it just then moves into the y'know: there's some things I have to do. And we can, you know, I often say: we can do it the easy way or the hard way. I'm always up for doing things the easy way; what about you guys? (248)

Being transparent

Transparency was the foundation of the strengths-based relationship and the key to enabling workers to navigate the constantly shifting balance between inviting collaboration and asserting their authority. Interviewees often referred to it as honesty, but it went further than honesty to incorporate the drive to make information readily accessible and understood, to make visible what was hidden. Strengths-based workers were described as being transparent about child protection concerns, expectations and the likely outcomes of client decisions. They discussed their authority, the likelihood of disagreement and the involuntary nature of the relationship at the beginning and throughout the work. In all these discussions, they were to be ‘honest, brutally honest’ (102) and use simple ‘crystal clear’ (176) language that would facilitate client understanding:

For me strengths-based is honest. It's very honest, it's very transparent, it's very open about the [agency], about the process, about the tendencies of what might happen in a file, about the shared desired outcome .... And for me it's like here's the chain of how it works: if you do this and this is the outcome here's what happens next. And if you don't do this then here's the next step … here's how we tend to do things. Second step, third step, fourth step, fifth step based on the contingencies .... So it's not when these things happen it's because I changed my mind and I don't care about you anymore and don't care about your family anymore and I'm thinking bad thoughts, it's because as we talked about this, these are just the kinds of things that need to happen. I don't want them to happen but they have to happen (254).

This transparency had several functions. It supported the development of trust, earned through a very explicit process of sharing information and following through with promised consequences. It gave the relationship a sense of purpose and enabled clients to be as self-determining as possible. With a clear understanding of all pertinent information, they could make informed choices as to how to conduct themselves. It contributed to a sense of containment and safety that supported behavioural change. Importantly, it also helped to sustain the worker–client relationship as workers moved between different levels of directiveness within a strengths-based approach. Talking about the dual legal and therapeutic aspects of the relationship appeared to make it less likely that workers would get stuck in a supportive stance in which they felt unable to be directive without betraying or confusing clients (Oliver and Charles, 2015).

Attending to the interaction

This version of strengths-based practice required an ongoing attentiveness to the worker–client interaction. It meant being mindful about the ways in which words, tone and body language could support or undermine the relationship. Attending to the minutiae of the interaction helped workers to continually transmit their impartiality, presence and caring. It was perceived to soften the impact of their blunt honesty and was part of an ongoing process of checking and correcting their communication in order to support collaboration with clients.

Interviewees described techniques like tracking the client's meaning, using reflective statements and honouring the need of clients to take breaks during interviews. Three of the four workers credited their education in counselling and advanced communication and therapeutic skills as a support for this practice. The fourth spent considerable time negotiating with clients the relationship's ‘ground rules so we can both feel safe and we both feel heard and we both feel respected’ (176). She and another worker talked of attending to the relationship by keeping small commitments like arriving on time for meetings. Workers also talked about being mindful of the physical space in which they interacted with clients. In their eyes, how they sat with clients on the couch, took off their shoes or positioned furniture had the potential to either support or undermine collaboration:

I am calm and I'm grounded and I'm really thoughtful about the language, again that sounds silly but choosing the words. … And so my language, my physical presence, where I talk to people, the difference between me meeting clients in my office as opposed to the bloody boardroom; all of that then reinforces every day the relationships that I have (248).

Seeing clients as human

An important component of this version of strengths-based practice was seeing clients as fellow human beings. The four interviewees shared an ‘innate belief in the goodness of humankind’ (248) and all equated being human to being worthy of unconditional positive regard, respect and hope. Seeing clients as human also created a sense of connectedness. As one worker said, ‘I am a human being just like them, we are joined in that’ (102). The sense that ‘we're all human, we'll both make mistakes’ (176) helped these workers to see clients as having both strengths and areas for growth. It enabled workers to contextualise client behaviour and engendered feelings of caring and compassion that were very motivating:

The way that you do that has to always be respectful of the humanity of the person that you're working with. And therefore if it is it's going to be strengths-based, right? I don't view them as a monster through a lens, I actually: yes so you busted somebody's head open and you then blew up a house; none of that stuff is excusable, but that doesn't mean you're not a human being anymore. And so how do we connect with you as a human being while still doing the stuff that we need to do in response to the behaviours that, that you demonstrated .... So they understand clearly what could happen legally that might not be nice stuff, or it might be ok stuff at the same time they're hearing it from a frame of: I really care for you I want to see something positive come out of this (254).

It was important that these feelings, and the underlying conceptualisation of the humanity of clients, were genuine. This served to keep in check worker authority, ensured that the approach's focus on strengths did not become a cynical exercise in manipulation and facilitated client engagement, and the continuation of the strengths-based relationship even when workers had to act against client wishes.

Judging impartially

The final element of this version of strengths-based practice was the ability to manage preconceptions and emotions so that judgements were impartial and fair. All four interviewees acknowledged that part of their job was to make judgements, but all stressed that, as one put it, ‘my job is to have open ears and an open mind and hear my client’ (176). There was both a cognitive and emotional aspect to judging impartially. It involved understanding client behaviour with reference to its broader context. This meant holding in mind multiple perspectives, building an understanding of both client strengths and challenges, and seeing all behaviour as meaningful by:

… looking past the cover of the book and look(ing) at the content of the book .... We're all victims of circumstance in some way, shape or form, maybe not victims but we're all products of circumstance and perhaps there's a reason why this person acts the way they do (102).

Judging impartially also involved deliberately working at being calm and ‘present in the moment’ (248). This ensured that the worker's judgement was not impaired and the relationship was not undermined by reactivity. It required emotional self-regulation to ensure ‘you didn't inject something into that relationship that poisons it for future collaboration’ (254).

Limitations

The description of the ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ version of strengths-based practice was constructed from interviews with four front line workers. More research is needed, in this and other child protection agencies, to evaluate the extent to which it resonates with others. To protect participant anonymity, information pertaining to worker characteristics like cultural identity, training and workplace location was not collected in this study, making it impossible to assess the ways in which these mediate perceptions of strengths-based practice. The study design also did not include mechanisms to verify interviewee accounts of their practice. Workers do not always act in the ways that they describe, and independent observations of practice would have helped to clarify the extent to which participants accurately represented their work.

Discussion

The practitioners in this study who saw themselves as able to do strengths-based practice in all child protection situations described navigating a continually shifting balance of collaboration and directiveness with their clients. They echoed Berg and Kelly's (2000) position that rather than deny their own expertise in their efforts to support the client's role as expert, they could offer it as a resource for collaborative work. This fluid relationship with power reflects Turnell and Edward's (1999) position that partnership and paternalism co-exist on a continuum and the strengths-based worker will move up and down this continuum over the life of a case. It reflects the dual role of the solution-focused therapist who assumes a ‘one down’ position both as a strategic move and as part of a genuine commitment to client self-determination.

This complex relationship with power contrasts with that promoted in the original Kansas approach and many descriptions of strengths-based practice. These emphasise the worker's rejection of the expert role in favour of perceiving expertise to lie solely with the client. Power is conceptualised as a relatively unidirectional and stable force, with the worker's job being to facilitate its transfer into the hands of the client through empowerment strategies. It reflects the common perception of professional power in social work as inherently problematic and inconsistent with such ideals as self-determination and empowerment (Bar-On, 2002).

The problem with this perception of power is that it appears to reflect neither the worker's nor the client's reality in child protection settings. The person-centred principles embodied by the Kansas approach, in which clients are free make their own decisions within an actualising therapeutic relationship, are incompatible with the child protection worker's mandated role (Murphy et al., 2013). Even when involved on a voluntary basis, child protection clients still perceive workers to, at best, exercise a constantly renegotiated combination of hierarchical ‘power over’ and collaborative ‘power with’ them (Dumbrill, 2006). In his description of the strengths perspective, Saleebey (2012) talks about adopting a ‘both/and’ position to acknowledge that clients have both strengths and challenges. This study suggests that an important part of translating the strengths perspective to child protection work is to make explicit the application of the ‘both/and’ position to the question of power. Social worker power can be both productive and oppressive (Tew, 2006) and strengths-based child protection requires that both client power and worker power be supported.

The fact that all but four interviewees in this study were attempting to enact versions of strengths-based practice that were ill-suited to their mandated role and for which there was little evidence of success in child protection settings suggests the need for better differentiation between generic strengths-based approaches and those adapted specifically for child protection work. Workers are more likely to implement programmes they perceive to be useful, adapted to fit the immediate context (Berkel et al., 2011) and part of a shared organisational vision (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). Child welfare agencies would be well advised to promote one model of strengths-based practice that has been developed specifically for child protection work and is described in the detail that makes implementation fidelity more likely (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ appears to provide important details as to what such models mean for worker–client relationships.

Balancing partnership and paternalism

‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ included four relational strategies supporting workers to navigate the constant shifts between collaborative and directive positions. The first, attending to the worker–client interaction, necessitated acute sensitivity to the conditions for productive communication. This sensitivity is promoted explicitly in the strengths-based child protection literature and reflects its solution-focused origins as a therapeutic approach. As Turnell and Edwards (1999) state, ‘it is the small increments of careful interaction that are the fundamental building blocks of creating cooperation between worker and family’ (p. 137).

The second element, transparency, is also a well-discussed element of strengths-based child protection practice. There are few texts on the approach that do not urge the worker to be open about child protection concerns and the worker's role, goals and expectations. There has been little emphasis, however, on the need to move beyond initial explanations of the worker's role and authority to discuss the unequal, non-consensual and shifting nature of the relationship on an ongoing basis. This was not only important in this study, but has been found significant in work focusing on effective practices with mandated clients (Rooney, 2009; Trotter, 2006; Trotter and Ward, 2013).

Much writing about work with mandated clients portrays the client as a rational decision maker who is motivated to engage in change if it is in his interests so to do. To make rational decisions the client needs reliable information and this makes transparency about power and process important throughout the life of a case. Such transparency enables both worker and client to perform their roles (Barber, 1991; Rooney, 2009; Trotter, 2006). These are not always clear to child protection clients; Trotter found that clients rarely perceived their worker to hold a dual surveillance and helping role, although those who did tended to have better outcomes (Trotter, 2006). Ongoing transparency about the relationship maximises congruence between worker and client expectations, which in turn increases the chance that clients will experience the relationship as supportive (Svensson, 2003). It makes visible the microclimate of sanctions and awards for the client's goal-oriented efforts that appears important in mandated relationships (Harris, 2008; Trotter and Ward, 2013), particularly for clients with psychopathy (Ross et al., 2008), depression, avoidant behaviour, multiple interpersonal problems and difficulties making relationships (Orsi et al., 2010). These clients are common in child protection work.

The third element supporting workers to move back and forth between asserting authority and inviting maximum client collaboration was the ability to make impartial judgements. Strengths-based child protection writers have discussed the need to remain open to multiple perspectives and to judge the client's situation in its broadest possible context but have tended not to name these as elements of impartiality or fairness or to examine the place of these concepts in the work. This may be important in light of this study and recent criminal justice research suggesting that relationships perceived to be ‘firm, fair and caring’ (Kennealy et al., 2012, p. 1) had lower recidivism rates. It appears that clients are more willing to meet expectations and can access a wider range of acceptable responses when they feel treated with a fair balance of care and control (Skeem et al., 2007).

The emotional element of impartiality is also not generally discussed as important to strengths-based practice. Yet the workers in this study who appeared most able to make the approach work stressed the role played by emotional self-regulation in enabling them to thoughtfully weigh competing perspectives and attend to the client. This reinforces recent findings that parents value child protection workers who are calm, non-anxious and non-reactive (Schreiber et al., 2013). It suggests the need to draw clearer linkages between the ability to do strengths-based child protection practice and evidence that child protection workers need significant emotional support (Ruch, 2007).

The final element of ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ was thinking of clients as fellow human beings. This engendered a sense of respect, caring and connection, and was an integrative idea in that it helped workers to accept that clients had both negative and positive features. As suggested by Grant and Cadell (2009), normalising worker and client struggles as part of the human condition was important to sustaining the strengths-based relationship. A humanistic orientation has always been part of strengths-based practice; as Kisthardt (2012) said, ‘by realizing that there is more in our shared experience as human beings that make providers more like participants than different from them, we gain the courage to be warm, caring, empathic, and genuinely affirming of people's own visions’ (p. 66). However, the strengths-based child protection literature has made little explicit use of the idea that clients and workers share a common humanity. In light of the fact that this idea was more salient for interviewees than common exhortations to see the client as experts or equals, it may be worth more attention.

Conclusion

It has been suggested that ethical dialogue requires that all parties can inform the agenda, speak plainly and receive support for marginalised views (Houston et al., 2011). In addition, ‘attention should be given to creating the most conducive physical surroundings and organizational ambience … [and] there ought to be an awareness of the different forms of power’ (Houston et al., 2011, p. 294). ‘Enacting firm, fair and friendly practice’ may be one way to create these conditions within the limits of the mandated worker–client relationship. It summarises the relational model held by the few workers in this study who appeared able to consistently implement strengths-based child protection practice in the ways envisaged by its key theorists. It situates strengths-based practice in the shifting power dynamics of worker–client relationships founded on transparency and nurtured by attentiveness, impartiality and a belief in our shared humanity. It may be a useful model for individuals seeking to navigate relationships reconciling their own authority and expertise with the authority and expertise of their clients. For child welfare agencies interested in implementing strengths-based practice, it provides more clarity about an approach that appears to be useful, popular and congruent with the statutory role.

References

- Antle B. F., Barbee A. P., Christensen D. N., Martin M. H. Solution-based casework in child welfare: Preliminary evaluation research. Journal of Public Child Welfare. 2008;2(2):197–227. [Google Scholar]

- Antle B. F., Christensen D. N., van Zyl M. A., Barbee A. P. The impact of the Solution Based Casework (SBC) practice model on federal outcomes in public child welfare. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36:342–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On A. A. Restoring power to social work practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2002;32(8):997–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Barber J. Beyond Casework. London: Macmillan; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Berg I. K., Kelly S. Building Solutions in Child Protective Services. New York: W.W. Norton; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C., Mauricio A. M., Schoenfelder E., Sandler I. N. Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science. 2011;12(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyas J., Wind L. H., Kang S. Y. Exploring the relationship between employment-based social capital, job stress, burnout, and intent to leave among child protection workers: An age-based path analysis model. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(1):50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn A. London: NSPCC; 2013. Signs of Safety in England: An NSPCC Commissioned Report on the Signs of Safety Model in Child Protection. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P., Berg I. K. Co-constructing cooperation with mandated clients. Social Work. 2001;46(4):361–74. doi: 10.1093/sw/46.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Shazer S. In: Keys to Solution in Brief Therapy. Norton W.W., editor. New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Child Protection. A Report on the 2010 Signs of Safety Survey. Perth: Government of Western Australia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dumbrill G. C. Parental experience of child protection intervention: A qualitative study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J. A., DuPre E. P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):327–50. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson H. Working with violence, the emotions and the psycho-social dynamics of child protection: Reflections on the Victoria Climbié case. Social Work Education. 2005;24(7):781–95. [Google Scholar]

- Grant J., Cadell S. Power, pathological worldviews and the strengths perspective in social work. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2009;90(4):425–30. [Google Scholar]

- Harris B., Leather P. Levels and consequences of exposure to service user violence: Evidence from a sample of UK social care staff. British Journal of Social Work. 2012;42(5):851–69. [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. Engaging substance misusers through coercion. In: Calder M., editor. The Carrot or the Stick? Towards Effective Practice with Involuntary Clients in Safeguarding Children Work. London: Russell House Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Healy K., Meagher G., Cullin J. Retaining novices to become expert child protection practitioners: Creating career pathways in direct practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2009;39(2):299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Houston S., Spratt T., Devaney J. Mandated prevention in child welfare: Considerations from a framework shaping ethical inquiry. Journal of Social Work. 2011;11(3):287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Idzelis Rothe M., Nelson-Dusek S., Skrypek M. Innovations in Child Protection Services in Minnesota: Research Chronicle of Carver and Olmsted Counties. St Paul, Minnesota: Wilder Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kennealy P. J., Skeem J. L., Manchak S. M., Eno Louden J. Firm, fair, and caring officer–offender relationships protect against supervision failure. Law and Human Behavior. 2012;36(6):496–505. doi: 10.1037/h0093935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisthardt W. Integrating the core competencies in strengths-based, person-centered practice: Clarifying purpose and reflecting principles. In: Saleebey D., editor. The Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice. Upper Saddle River: N.J, Pearson Education Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D., Duggan M., Joseph S. Relationship-based social work and its compatibility with the person-centred approach: Principled versus instrumental perspectives. British Journal of Social Work. 2013;43(4):703–19. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C. ‘Making strengths-based practice work in child protection: Frontline perspectives’. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia; 2014. unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C., Charles G. Which strengths-based practice: Reconciling strengths-based practice and mandated authority in child protection work. Social Work. 2015 doi: 10.1093/sw/swu058. Advance Access published January 19, 2015. 10.1093/sw/swu058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi M. M., Lafortune D., Brochu S. Care and control: Working alliance among adolescents in authoritarian settings. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2010;27(4):277–303. [Google Scholar]

- Parton N. Changes in the form of knowledge in social work: From the social to the informational? British Journal of Social Work. 2008;38(2):253–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp C., Saleebey D., Sullivan W. The future of strengths-based social work. Advances in Social Work: Special Issue on the Futures of Social Work. 2006;6(1):79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp R., Lane D. “Knowing” the effectiveness of strengths-based case management with substance abusers. In: Saleebey D., editor. The Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice. Upper Saddle River, Pearson Education Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney R. H. Strategies for Work with Involuntary Clients. New York: Columbia University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ross E. C., Polaschek D. L. L., Ward T. The therapeutic alliance: A theoretical revision for offender rehabilitation. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13(6):462–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch G. Reflective practice in contemporary child-care social work: The role of containment. British Journal of Social Work. 2007;37(4):659–80. [Google Scholar]

- Saleebey D. The Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice. New York: Longman Publishing; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleebey D. The Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Education Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber J. C., Fuller T., Paceley M. S. Engagement in child protective services: Parent perceptions of worker skills. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35:707–15. [Google Scholar]

- Skeem J. L., Louden J. E., Polaschek D., Camp J. Assessing relationship quality in mandated community treatment: Blending care with control. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(4):397–410. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrypek M., Idzelis M., Pecora P. Signs of Safety in Minnesota: Parent Perceptions of a Signs of Safety Child Protection Experience. St Paul, Minnesota: Wilder Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K. Social work in the criminal justice system: An ambiguous exercise of caring power. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology & Crime Prevention. 2003;4(1):84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tew J. Understanding power and powerlessness: Towards a framework for emancipatory practice in social work. Journal of Social Work. 2006;6(1):33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. Interpretive Description. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter C. Working with Involuntary Clients: A Guide to Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter C., Ward T. Involuntary clients, pro-social modelling and ethics. Ethics and Social Welfare. 2013;7(1):74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Turnell A. The Signs of Safety: A Comprehensive Briefing Paper. Perth: Resolutions Consultancy; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turnell A., Edwards S. Signs of Safety: A Safety and Solution Oriented Approach to Child Protection Casework. New York: W.W. Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turnell A., Essex S. Working with Denied Child Abuse: The Resolutions Approach. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turnell A., Lohrbach S., Curran S. Working with involuntary clients in child protection: Lessons from successful practice. In: Calder M., editor. The Carrot or the Stick? Towards Effective Practice with Involuntary Clients in Safeguarding Children Work. Dorset: Russell House; 2008. pp. 104–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler J., Hogg V. Signs of Safety and the child protection movement. In: Franklin C., Trepper T., Gingerich W., McCollum E., editors. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy: A Handbook of Evidence-Based Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]