Abstract

The well-documented day-to-day and long-term experiences of job stress and burnout among employees in child welfare organisations increasingly raise concerns among leaders, policy makers and scholars. Testing a theory-driven longitudinal model, this study seeks to advance understanding of the differential impact of job stressors (work–family conflict, role conflict and role ambiguity) and burnout (emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation) on employee disengagement (work withdrawal and exit-seeking behaviours). Data were collected at three six-month intervals from an availability sample of 362 front line social workers or social work supervisors who work in a large urban public child welfare organisation in the USA. The study's results yielded a good model fit (RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.94). Work–family conflict, role ambiguity and role conflict were found to impact work withdrawal and exit-seeking behaviours indirectly through burnout. The outcome variable, exit-seeking behaviours, was positively impacted by depersonalisation and work withdrawal at a statistically significant level. Overall, findings, at least in the US context, highlight the importance of further examining the development of job burnout among social workers and social work supervisors working in child welfare settings, as well as the utility of long-term administrative strategies to mitigate risks of burnout development and support engagement.

Keywords: Burnout, employee disengagement, exit-seeking behaviours, job stress, work withdrawal, work–family conflict

Introduction

To meet its service-focused mission, the social work profession is reliant on competent and engaged workers. Yet, social workers are considered high-risk for job stress and burnout. Although no definitive statistics exist on the prevalence rates of stress and burnout in social work, findings from previous studies suggest that social workers are prone to experiencing both (Arrington, 2008; Lloyd et al., 2002). Stress and burnout have attracted the attention of scholars and practitioners because of potential hazards posed to social workers' well-being and effectiveness (e.g. job satisfaction: Evans et al., 2006; organisational commitment: Lambert et al., 2006; turnover: Acker, 2012; Kim and Stoner, 2008).

Challenges resultant from job stress and burnout are also, in particular, experienced by social workers in child welfare settings (Lizano and Mor Barak, 2012; Travis and Mor Barak, 2010; Sprang et al., 2011). Child welfare—which is characterised by high job demands, low wages, high caseloads and need for quality supervision—has been described as one of the most challenging professions (AECF, 2003; Kim, 2011). Although a preponderance of published studies are in North America, these challenges are shared in child welfare settings across the world (Burns, 2011). Yet, limited empirical evidence exists to provide guidance on which types of stressors, and subsequent burnout, influence employee disengagement among employees (particularly social workers) in child welfare settings.

What is the prolonged impact of different types of stressors on an individual's proclivity to quit? Which dimensions of burnout—emotional exhaustion or depersonalisation—have the most impact on one's propensity to psychologically retreat from work activities? This study addresses these questions by examining which stressors and burnout factors ‘tip the scale’ or increase the likelihood of disengagement over time. We specifically test a theory-driven longitudinal model of antecedents to engagement among social workers and social work supervisors based in a public child welfare organisation in the USA. This is an important line of inquiry because job stress and engagement link to organisational effectiveness (Blacksmith and Harter, 2011; Louis et al., 2010). Building a quality-driven and engaged workforce requires in-depth analyses of stress-related factors that may hinder worker effectiveness (Simona et al., 2008).

Conceptual model and research hypotheses

Definitional clarity

Work stressors

Broadly defined, work stress is the ‘harmful physical and emotional responses that occur when the requirements of the job do not match the capabilities, resources, or needs of the worker’ (NIOSH, 1999, p. 6). Occupational role stress emerges as individuals experience conflict, ambiguity or overload in work-related roles (Dobreva-Martinova et al., 2002; Tetrick, 1992). Work–family conflict is conceptually defined as inter-role conflict resulting from an incompatibility in work and family responsibilities (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985; Michel et al., 2011). Conceptualised in Robert Kahn's (1964) seminal work, role conflict refers to the conflicting demands that employees face, whereas role ambiguity relates to the lack of clarity in the expectations of others.

Job burnout

Chronic work-related stressors have prolonged effects on employees resulting in burnout (Lee and Ashforth, 1996; Maslach et al., 2001; Schaufeli et al., 2009). Burnout is a multidimensional construct, yet, from a theoretical and practical perspective, ‘the overall concept of burnout may sometimes help us to advance our knowledge in a more thorough way than research on the separate, underlying dimensions’ as well as to streamline study findings (Brenninkmeijer and VanYperen, 2003, p. i17). Despite this, we focus on two dimensions of burnout. Emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation are stress responses resulting from prolonged exposure to overload and social conflict in the workplace (Maslach, 1998; Maslach et al., 2001).

Emotional exhaustion, central to job burnout, refers to feelings of exhaustion resulting from overwhelming demands (Maslach et al., 2001). Feelings of emotional exhaustion subsequently lead to depersonalisation. Depersonalisation is a protective state of cynicism that spurs dissonance, either cognitive or emotional, with others as a coping strategy for work demands and exhaustion (Halbesleben and Buckley, 2004).

Disengagement

Employee disengagement can be a psychological form of ‘leaving’ one's job while remaining employed (Burris et al., 2008). Hence, work withdrawal and exit-seeking behaviours are considered forms of disengagement. Work withdrawal is a way of ‘zoning out’ or a form of job neglect by psychologically detaching from work-related tasks or organisational activities (Hopkins et al., 2010; Kidwell and Robie, 2003; Rusbult et al., 1988; Withey and Cooper, 1989). Examples of withdrawal behaviours include not putting forth concerted effort in work tasks, avoiding co-workers or misusing organisational time (Kidwell and Robie, 2003; Naus et al., 2007). When engaging in exit-seeking behaviours (herein referred to as exit), employees contemplate quitting by actively looking for a new job (Travis and Mor Barak, 2010). As such, exit reflects a form of psychological disengagement (Burris et al., 2008; Naus et al., 2007). Thus, work withdrawal and exit as forms of disengagement are well-documented predictors of turnover (Griffeth et al., 2000), which may result in lowered levels of innovation and worker creativity (Krueger and Killham, 2006).

Primary model and research hypotheses

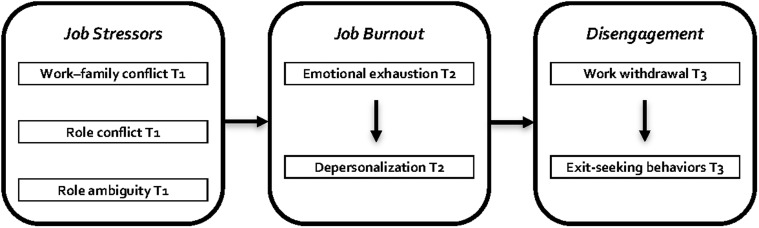

Figure 1 depicts relationships among work stressors, job burnout and disengagement over time. The proposed conceptual model reflects the long-term negative effects of work stressors on employee disengagement through job burnout. Relationships among study variables are supported by theoretical and empirical evidence. Role theory (Biddle, 1986; Kahn et al., 1964) offers insight into how job stress affects worker outcomes including burnout and disengagement. Burnout is postulated to develop due to chronic stressors in the workplace resulting from incongruence between the worker and the job (Maslach, 2003) making role theory a strong point of departure in helping explain antecedents to burnout (Cordes and Dougherty, 1993). According to role theory, organisational roles are ascribed within the context of organisational structures, processes and norms (Dobreva-Martinova et al., 2002) and are determined by employees' position or status (Biddle, 1986). Organisational context and status levels can influence how well employees perform and whether they experience conflicting demands and ambiguous job situations (Dobreva-Martinova et al., 2002). Using role theory as a frame, burnout and associated disengagement can emerge as employees experience challenges in balancing competing needs of work and family or home life (work–family conflict), incompatibility with work roles (role conflict) and lack of clear expectations about one's work roles (role ambiguity) (Kim and Stoner, 2008; Rupert et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Study conceptual model

Burnout

Chronic exposure to work-related stressors is a well-documented contributor to burnout (Boyas and Wind, 2010; Kim and Stoner, 2008; Lloyd et al., 2002; Maslach, 1998, 2006). Researchers found that work–family conflict is among occupational stressors that incite job burnout (Allen et al., 2000; Maslach, 2005; Schaufeli et al., 2009). Positive relationships between role conflict and ambiguity and job burnout have been documented (Cordes and Dougherty, 1993; Lee and Ashforth, 1996; Örtqvist and Wincent, 2006). Accordingly, occupational demands associated with work–family conflict, role conflict, role ambiguity and generalised job stress are linked to a greater propensity for burnout (Nissly et al., 2005; AECF, 2003; Boyas and Wind, 2010; Kim, 2011; Regehr et al., 2004). Thus:

Hypothesis 1: Role conflict, role ambiguity, and work–family conflict at Time 1 will have a positive relationship with burnout dimensions at Time 2.

Relationship between burnout dimensions

Distinguishing the relationship between emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation serves as a starting point to understanding the differential impact of burnout on disengagement. Researchers found that emotional exhaustion elicits a worker response resulting in depersonalisation of clients being served and co-workers to create an emotional distance from the stressful work condition (Maslach et al., 1996):

Hypothesis 2: Emotional exhaustion leads to depersonalisation.

The mediating impact of job burnout

Researchers found that job burnout adversely influences work-related engagement (International Labour Office, 1993; Maslach et al., 2001) and high turnover rates (Mor Barak et al., 2001; Zlotnik et al., 2005). In a meta-analysis of 115 empirical studies, Swider and Zimmerman (2010) found that burnout factors correlated with absenteeism, turnover and job performance. As stated by Montero-Marín et al. (2009), workers experiencing burnout are characterised by ‘a lack of personal involvement in work-related tasks, leading one to give up as a response to any difficulty’ (p. 11). From this vantage point, work withdrawal is a manifestation of burnout factors and can result in work behaviours that seemingly reflect a decision to limit work-related activities. As such, job burnout creates a cognitive distance that buffers against stressful work experiences (Lee and Ashforth, 1996; Maslach et al., 2001). This leads to reduction in motivation or an increase in frustration with the job, which may foster development of attitudes and behaviours that reflect disengagement and psychological withdrawal in the workplace (Halbesleben and Buckley, 2004):

Hypothesis 3a: Emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation at Time 2 will positively impact disengagement at Time 3.

Hypothesis 3b: Workplace stressors at Time 1 will have a positive and indirect relationship, through burnout dimensions at Time 2, on disengagement at Time 3.

Relationship between engagement behaviours

Withey and Cooper (1989) found that job neglect (similar to work withdrawal) and exit were related because both are forms of detaching oneself from the job. As people withdraw, they may have greater propensity to move towards leaving (exit). Hence, withdrawal can result in exit, particularly when alternatives are either perceived as or actually not an optimal choice (Withey and Cooper, 1989). In a cross-sectional examination of public child welfare, we found a direct and positive relationship between work withdrawal and exit-related behaviours (Travis and Mor Barak, 2010). Although it does not represent ‘exit’ as conceptualised in this study, actual turnover has been found to be precipitated by limited engagement in work-related tasks and organisational activities (Griffeth et al., 2000; Withey and Cooper, 1989). Thus, we hypothesised:

Hypothesis 4: Work withdrawal will positively impact exit-seeking behaviours.

Competing model

Overall, job-related stressors are well-documented predictors of undesirable worker outcomes (e.g. counterproductive work behaviours and intention to leave) (Mor Barak et al., 2001; Travis and Mor Barak, 2010; Williams et al., 2001). Increased harmony between work and life demands and lessened work–family conflict have been leading predictors of engagement-related factors (Allen et al., 2000). Thus, we tested a competing model that explored direct relationships between work stressors and disengagement. By examining results from the primary and competing model, we were able to determine whether stressors directly affected disengagement or work through burnout.

Methods

Design and context

This three-wave longitudinal panel study was conducted as a part of a large-scale study under the auspices of a university-based training centre for children and family services employees. It builds on previous research on employee responses to undesirable work situations and retention in child welfare organisations (Nissly et al., 2005; Travis and Mor Barak, 2010; Travis et al., 2011; Lizano and Mor Barak, 2012). Data were collected at three six-month intervals from an availability sample of 362 employees at large urban public child welfare agency using a self-report questionnaire. Ninety-five per cent of the sample described their job position as social workers or social work supervisors. In addition, 50 per cent reported having a formal social work education or training at either the bachelor or graduate levels.

Participants were recruited while attending one of several child welfare skill and knowledge building trainings. The voluntary nature and study details were explained during the informed-consent process. Free lunch was offered as compensation for participation. Respondents completed the baseline questionnaire in a vacant training room. Questionnaires with unique identifiers were mailed to participants at six- and twelve-month time points. The same measurement instrument was used for all data collection. Table 1 presents demographic information for the study sample. A University's Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| % | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36.83 (range: 21–70) | 11.46 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 16.3 | ||

| Female | 83.4 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 30.7 | ||

| Latino(a)/Hispanic | 29.9 | ||

| African American/black | 21.9 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 12.2 | ||

| Other | 4.2 | ||

| Tenure (years) | 6.16 (range: < 1–36) | 6.73 | |

| 0–5 | 62.4 | ||

| 6–10 | 18.5 | ||

| 11–15 | 10.9 | ||

| 16–20 | 6.9 | ||

| 21–25 | 0.7 | ||

| ≥ 26 | 0.7 | ||

| Position | |||

| Direct service provider | 84.8 | ||

| Supervisor | 15.2 | ||

| Educational background | |||

| Bachelor's degree | 34.3 | ||

| Master's degree | 63.10 | ||

| Ph.D. | 0.8 | ||

| Other | 1.1 |

Measures

All measures were captured using a six-point Likert scale. Response options for all items ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. Reverse coding was used to ensure that higher-scale scores corresponded with higher levels of work–family conflict, role conflict, emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, work withdrawal or exit. A composite score was created for each scale.

Work–family conflict

Beatty's (1996) three-item work–family conflict scale was used to measure conflict between work and family demands. Scale items included ‘My job keeps me away from my family too much’ and ‘I have a good balance between my job and my family life’. This scale yielded a Cronbach's alpha reliability value of 0.75.

Role conflict and role ambiguity

As facets of work stress, role conflict and role ambiguity were measured using Rizzo, House and Lirtzman's (1970) scale items. Eight role conflict and six role ambiguity items were used. Scale items for role conflict and ambiguity included items such as ‘I have clear planned goals and objectives for my job’ and ‘I receive incompatible tasks from two or more people’. Role ambiguity and role conflict, respectively, had Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.83 and 0.85.

Job burnout

Emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation were measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach and Jackson, 1981). Two of three subscales corresponded to dimensions of emotional exhaustion (nine items) and depersonalisation (five items). The third subscale, personal accomplishment, was excluded based on theoretical and empirical reasons. Theoretically, personal accomplishment more accurately describes a personality characteristic and not a symptom of job burnout (Cordes and Dougherty, 1993). Empirically, MBI's personal accomplishment subscale has demonstrated a weaker relationship with the other two dimensions of job burnout (Lee and Ashforth, 1996); when used longitudinally, it has not demonstrated invariance over time (Kim and Ji, 2009). The two MBI subscales yielded a Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient of 0.94 (emotional exhaustion) and 0.81 (depersonalisation).

Employee disengagement

Levels of disengagement were measured using Rusbult et al.'s (1988) job neglect (six items) and exit scales (four items), which measure an individual's self-reported generalised tendencies to engage in withdrawal or exit-seeking behaviours. These scales were tested in different variations across three studies by Rusbult et al. (1988) and yielded reliability coefficients ranging from 0.69 to 0.82 for job neglect and from 0.76 to 0.97 for exit. In the current study, the job neglect and exit scales respectively yielded a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.73 and 0.89.

Covariates

Respondents' self-reported age, gender and organisational tenure were derived from demographic questionnaire items. The covariate of gender was dummy coded in preparation for analysis (male = 0, female = 1).

Analytic procedures

Data preparation

Missing data due to attrition and other extraneous variables are considered commonplace and are particularly prevalent in longitudinal studies (Little and Rubin, 2002). Patterns of missing data among the central study variables were examined prior to analysis. Three hundred and sixty-two respondents participated in the study at baseline, 187 participated at Time 2 and 133 participated in all three waves of data collection. Preliminary examination suggested that data were missing at random as defined by Rubin (1996). To test whether job stress, work–family conflict, emotional exhaustion or depersonalisation predicted missing data, a series of logistic regression models were conducted. Logistic regression analyses yielded no significant relationships among study variables and patterns of missing data. Furthermore, relationships among study covariates (demographic characteristics) and missing data were also examined via logistic regression, with results suggesting a null relationship between age, sex and job tenure and whether or not a participant missed a data collection point.

Using IBM's AMOS 18 software, a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimate approach was chosen to address missing data in the sample due to the potential bias that older methods such as case deletion and mean imputation can introduce (Schafer and Graham, 2002).

Study variables were examined for normality prior to analysis. Deviation from normality among the central study variables was minimal and within the 3.0 maximum skewness value (absolute value) recommended when conducting structural equation modelling using FIML estimation methods during analysis (Kline, 2010). Skewness among study variables ranged from –0.09 to 0.51, whereas kurtosis ranged from –1.24 to 0.019.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the central study variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and interitem correlation values

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Work–family conflict(T1) | 9.68 | 4.14 | 1 | |||||

| 2 Role conflict(T1) | 30.45 | 8.51 | 0.262** | 1 | ||||

| 3 Role ambiguity(T1) | 14.41 | 5.04 | 0.186** | 0.156** | 1 | |||

| 4 Emotional exhaustion(T2) | 30.11 | 10.76 | 0.253** | 0.192* | 0.146 | 1 | ||

| 5 Depersonalisation(T2) | 11.23 | 5.02 | 0.121 | –0.015 | 0.146 | 0.436** | 1 | |

| 6 Work withdrawal(T3) | 14.27 | 5.34 | 0.117 | 0.207* | 0.118 | 0.424** | 0.358** | 1 |

| 7 Exit-seeking behaviours(T3) | 12.65 | 6.65 | 0.18 | –0.014 | 0.222* | 0.478** | 0.401** | 0.458** |

* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01.

Path analysis

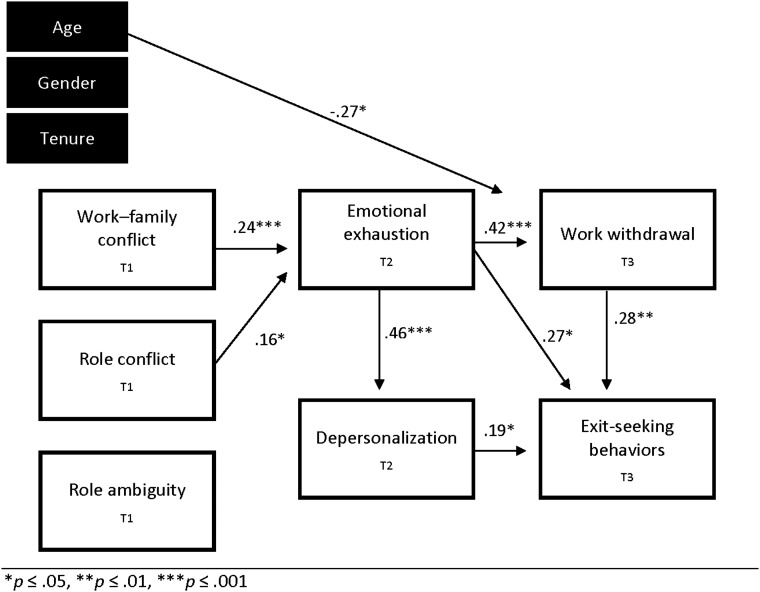

A form of structural equation modelling, path analysis was employed to test the hypothesised conceptual model. Path analysis is an approach that models multivariate interrelationships of observed variables and allows for the simultaneous testing of multiple relationships (Bollen, 2005). A two-step model-testing process was employed, yielding two models. The first model tested the theorised direct and indirect relationships between workplace stressors, emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and the outcomes of exit and work withdrawal over time. The impact of control variables on the outcomes of interest was also tested in Model 1. A second trimmed model was analysed after removing all insignificant paths from Model 1. The model presenting only significant paths is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Path analytic model of workplace stressors, burnout and disengagement over time (standardised coefficients)

Results

Fit indices

Multiple indices were used to assess the fit of the primary and competing model as recommended in the structural equation modelling literature (Kline, 2010). Although we used the chi-square test, other fit indices were also used because the chi-square test is known to be sensitive to sample size (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was used to assess model approximation to population parameters (Kline, 2010), whereas the comparative fit index (CFI) and the normed fit index (NFI; Bentler, 1990) were used to examine the improvement of fit between the full and trimmed models.

Full model

The full hypothesised conceptual model yielded a statistically significant chi-square value of X2 (12) = 27.25, p = 0.007. However, the remaining fit statistics met criterion suggesting good model fit (RMSEA ≤ 0.05, NFI and CFI ≥ 0.90). The full model included an RMSEA value of 0.06, a CFI value of 0.96 and an NFI value of 0.94.

Competing model

The competing model yielded a statistically significant chi-square value of X2 (13) = 30.3, p = 0.007. However, the remaining fit statistics again suggested an acceptable model fit (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.85).

Path coefficients

Primary model

Standardised coefficients for the model paths are presented in Figure 2. Table 3 also provides the full and competing model path analysis results. Findings suggest that work–family conflict (β = 0.24) and role conflict (β = 0.16) significantly and positively impacted emotional exhaustion, with work–family conflict having a greater influence on development of emotional exhaustion than role conflict. Work–family conflict and role conflict accounted for 13.6 per cent of the explained variance in emotional exhaustion. No statistically significant relationships were found between role ambiguity and burnout components (i.e. emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation). Emotional exhaustion significantly impacted depersonalisation (β = 0.45) and accounted for 22.3 per cent of its variance, whereas no other predictor variables were found to have a statistically significant relationship with depersonalisation.

Table 3.

Full and competing model path analysis results

| Outcome variable | Independent variable | b | SE b | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full model | ||||

| Emotional exhaustion(T2) | Work–family conflict(T1) | 0.65 | 0.20 | 0.24*** |

| Emotional exhaustion(T2) | Role conflict(T1) | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.16* |

| Emotional exhaustion(T2) | Role ambiguity(T1) | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Depersonalisation(T2) | Emotional exhaustion(T2) | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.46*** |

| Depersonalisation(T2) | Work–family conflict(T1) | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Depersonalisation(T2) | Role conflict(T1) | –0.06 | 0.05 | –0.10 |

| Depersonalisation(T2) | Role ambiguity(T1) | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Work withdrawal(T3) | Emotional exhaustion(T2) | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.42*** |

| Work withdrawal(T3) | Depersonalisation(T2) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Work withdrawal(T3) | Tenure(T1) | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| Work withdrawal(T3) | Sex(T1) | –1.70 | 1.15 | –0.12 |

| Work withdrawal(T3) | Age(T1) | –0.13 | 0.05 | –0.27* |

| Exit(T3) | Work withdrawal(T3) | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.28*** |

| Exit(T3) | Emotional exhaustion(T2) | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.27** |

| Exit(T3) | Depersonalisation(T2) | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.19* |

| Exit(T3) | Age(T1) | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Exit(T3) | Sex(T1) | 0.63 | 1.41 | 0.04 |

| Exit(T3) | Tenure(T1) | –0.12 | 0.11 | –0.12 |

| Trimmed model | ||||

| Emotional exhaustion(T2) | Work–family conflict(T1) | 0.67 | 0.20 | 0.25*** |

| Emotional exhaustion(T2) | Role conflict(T1) | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.17** |

| Depersonalisation(T2) | Emotional exhaustion(T2) | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.46*** |

| Work withdrawal(T3) | Emotional exhaustion(T2) | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.46*** |

| Work withdrawal(T3) | Age(T1) | –0.10 | 0.04 | –0.23** |

| Exit(T3) | Work withdrawal(T3) | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.26** |

| Exit(T3) | Depersonalisation(T2) | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.18* |

| Exit(T3) | Emotional exhaustion(T2) | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.29** |

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. Full model R2: emotional exhaustion (T2) = 0.14, depersonali-sation(T2) = 0.22, work withdrawal(T3) = 0.29, exit(T3) = 0.35. Trimmed model R2: emotional exhaustion(T2) = 0.12, depersonalisation(T2) = 0.21, work withdrawal(T3) = 0.26, exit(T3) = 0.34.

A statistically significant positive relationship was found between emotional exhaustion and outcomes of work withdrawal (β = 0.42) and exit (β = 0.27), with a stronger relationship existing between emotional exhaustion and withdrawal. Depersonalisation was found to have a positive and statistically significant relationship with exit (β = 0.19) but not work withdrawal. A positive relationship between withdrawal and exit was also found (β = 0.28). Age was the only control variable found to be positively related to any outcome of interest, with a negative relationship with withdrawal (β = –0.27). The path analytic model was found to account for approximately one-third of the variance in withdrawal (28.9 per cent) and exit (34.6 per cent). No significant direct paths were found between the predictor variables of work–family conflict, role conflict and role ambiguity (Time 1) and the outcome variables of withdrawal and exit (Time 3).

Competing model

The competing model yielded the same statistically significant paths as the primary model, demonstrating consistency among the relationships of variables in both models. The beta coefficients varied only slightly in the competing model. Work–family conflict (β = 0.25) and role conflict (β = 0.17) positively impacted emotional exhaustion. Emotional exhaustion significantly impacted depersonalisation (β = 0.46), withdrawal (β = 0.46) and exit (β = 0.29). Depersonalisation positively impacted exit (β = 0.18) and withdrawal (β = 0.26). Age was the only control variable demonstrating a statistically significant relationship with withdrawal (β = –0.23). No significant relationships were found between work–family conflict, role ambiguity and role conflict and the outcome variables of withdrawal and exit.

Discussion

Summary

Findings provide a nuanced perspective of interrelationships among workplace stressors, burnout and engagement over time. Key findings point to the central role that burnout plays in disengagement among front line social workers or social work supervisors in a child welfare setting. Previous studies examining stress and burnout among human service and child welfare social workers generally have not tested the components of the job stress construct (e.g. role conflict, role ambiguity) (Boyas and Wind, 2010; Kim and Stoner, 2008). Instead, studies often use a composite and this potential masks the unique contribution of each stress component to job burnout. This study has sought to fill this gap.

The hypothesised relationship (Hypothesis 1) between work stressors and burnout was partially supported. Work–family and role conflict were positive and significant predictors of emotional exhaustion—a finding congruent with the job burnout literature (Allen et al., 2000; Maslach, 2003; Peeters et al., 2005). Nevertheless, our finding of a null relationship between role ambiguity and burnout was novel and unexpected. Job burnout is theorised to be a result of chronic exposure to work stressors (Maslach, 2003, 2006)—a relationship that has received evidentiary support in previous studies (Kim and Stoner, 2008; Lee and Ashforth, 1996).

None of the three stressors (role conflict, role ambiguity and work–family conflict) directly affected depersonalisation. Each stressor was indirectly linked to depersonalisation through emotional exhaustion at statistically significant levels. Based on our conceptual model, these findings suggest that work stressors lead to feelings of cynicism (depersonalisation) through emotional exhaustion.

As posited in Hypothesis 2, emotional exhaustion was a significant correlate of depersonalisation. This is consistent with previous research (Ashill and Rod, 2011; Diestel and Schmidt, 2010). For example, in a longitudinal study of German nursing home and civil servant employees, Diestel and Schmidt (2010) found empirical support for the causal relationship between emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation.

Several facets of Hypothesis 3a were supported with emotional exhaustion positively impact both work withdrawal and exit over time; however depersonalisation was only a significant correlate of exit. Job burnout theories offer insight into these findings. The accumulative stress may place an emotional tax on workers, which can have adverse implications for engagement. Study findings also supported Hypothesis 3b. That is, burnout served as a mediator of work stressors on employee disengagement over time. In the primary model tested, we found that only stressors (work–family conflict and role conflict) affected disengagement (withdrawal and exit-seeking behaviours) through the burnout dimension of emotional exhaustion. Acker (2012) had similar findings in which emotional exhaustion served as mediator of role stress and intent to quit among a study of mental health providers (including social workers).

When testing the competing model, we found that none of the stressors directly predicted exit and work withdrawal over time. This is contrary to Hopkins et al.'s (2010) findings that showed job stress was the strongest predictor of work and job withdrawal behaviours. Yet, Hopkins examined a composite of stress (i.e. emotional exhaustion, role conflict and role overload) which differs from this study's emphasis on distinguishing types of stressors.

As hypothesised (Hypothesis 4), work withdrawal served as an antecedent of exit-seeking behaviours. This replicated our findings in a cross-sectional study of child welfare workers (Travis and Mor Barak, 2010). Griffeth et al. (2000) found in a meta-analyses of factors leading to turnover that lack of engagement precedes intention to leave and actual quitting.

Finally, we found that age was a significant correlate of withdrawal. In this, younger workers were more likely to report engaging in work withdrawal. In this accord, as proposed by Ng and Feldman (2009), generational differences can be explained by one's expectations and perceptions of the job itself as well as the labour market. Older workers may have greater flexibility in intra-organisational contract negotiation and problem resolution processes and, as a result, have less motivation to engage in withdrawal behaviours. Also, Ng and Feldman offer ‘self-preservation’ (p. 1068) as an explanation, in which older workers may be more weary of the perceived impact of age stereotypes on one's ability to ascertain a job elsewhere. This maturity may also spur a focus on putting others before oneself or cultivates greater suspension of self in these contexts.

Study strengths and limitations

Findings should be interpreted within the context of the study's limitations. The study may be limited in generalisability based on use of availability sampling. The study setting, a large public child welfare organisation in an USA-based urban locale, limits the external validity and precludes generalising findings in rural or suburban areas as well as other regions in the world. Data for the present study were drawn from self-reports, posing a threat of common source bias. Moreover, some scales used to reflect study constructs have known limitations and more study is needed within the context of child welfare or social work settings.

Despite these limitations, the study has strengths that allow our findings to contribute to a greater understanding of role of stress and burnout in the development of the disengaged worker. The study's longitudinal design afforded us the ability to test the complex interrelationships of stress, burnout and disengagement over time. Additionally, examining separate components of stress, burnout and disengagement painted a picture of the complex interrelationships among variables of interest.

Implications

Improving engagement goes beyond simply asking the right questions. Engaging employees requires a year-round focus on changing behaviours, processes and systems to anticipate and respond to your organisation's needs. From the leadership team to the front line employees, all levels within an organisation must commit to making these changes (Gallup, 2010).

This study has practice and research implications for human resource development in child welfare organisations and among social work professionals. At the practice level, the above quote emphasises the importance of developing structural mechanisms to support worker engagement at all levels. Policies and practices that may inadvertently foster burnout and disengagement need to be evaluated based on the impact on employee job performance, business results and client outcomes. At the same time, developing timely organisational-level interventions to deal with conflict associated with work–family fit and competing demands of work roles is essential. This may include helping workers express concerns and emotions as well as active coping skills as mechanisms for increasing engagement and dealing with role stress (Ng and Feldman, 2012; Stalker et al., 2007).

Amidst finding ways to prevent burnout and disengagement, leaders may consider what is working to help employees thrive. This is particularly relevant in child welfare settings in which workers experience emotional exhaustion, but are also satisfied with their jobs (Stalker et al., 2007). Through the strengths-based lens, leaders may gauge best practices and leverage organisational resources to create innovative solutions, build resilience, increase intention to stay and foster engagement.

Finally, researchers are encouraged to distinguish between forms of work stressors and burnout to allow for examination of the differential impact of distinct stressors and burnout dimensions on well-being. Concurrently, there is a need to advance understanding of supportive mechanisms that mitigate disengagement and bolster engagement among social work professionals. Exploring factors that encourage productive work attitudes and behaviours is a fruitful line of inquiry (Collins, 2008) and may inform interventions that promote an engaged workforce and meet the mission of social service organisations.

Conclusion

Given the positive link between engagement and the provision of quality services (Markos and Sridevi, 2010), service effectiveness can be indirectly impacted due to employees not fully engaging in job activities. This study offers a deeper examination of dimensions of work stressors and burnout as antecedents to disengagement among social workers and social work supervisors. Findings indicate that emotional exhaustion is an indirect and direct threat to engagement, highlighting the importance of further examining the development of job burnout among social workers in child welfare settings and administrative strategies that may mitigate potential obstacles to optimal organisational effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Paul Carlo, Director, Donna Toulmin, Director of Training, and the dedicated staff at the USC Center on Child Welfare for their unwavering support of this study. We also extend our gratitude to Harold Pyun for his work in data collection and management of the larger study. This study was funded by a Title IV-E Child Welfare Training grant.

References

- Acker G. M. Burnout among mental health care providers. Journal of Social Work. 2012;12(5):475–90. [Google Scholar]

- Allen T. D., Herst D. E., Bruck C. S., Sutton M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:278–308. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annie E. Casey Foundation (AECF) 2003. ‘The unsolved challenge of system reform: The condition of the frontline human services workforce’, available online at www.aecf.org/upload/publicationfiles/the%20unsolved%20challenge.pdf .

- Arrington P. Stress at Work: How Do Social Workers Cope?, NASW Membership Workforce Study. Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ashill N. J., Rod M. Burnout processes in non-clinical health service encounters. Journal of Business Research. 2011;64:1116–27. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty C. A. The stress of managerial and professional women: Is the price too high? Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1996;17:233–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle B. J. Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology. 1986;12:67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Blacksmith N., Harter J. Majority of American workers not engaged in their jobs. Gallup Wellbeing. 2011. 28 October, available online at www.gallup.com/poll/150383/Majority-American-Workers-Not-Engaged-Jobs.aspx .

- Bollen K. A. Encyclopedia of Biostastics, Online. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. ‘Path analysis. available online at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/0470011815 . [Google Scholar]

- Boyas J., Wind L. H. Employment-based social capital, job stress, and employee burnout: A public child welfare employee structural model. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(3):380–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brenninkmeijer V., VanYperen N. How to conduct research on burnout: Advantages and disadvantages of a unidimensional approach in burnout research. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;60(Suppl. 1, pp):i16–20. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns K. ‘“Career preference”, “transients” and “converts”: A study of social workers’ retention in child protection and welfare'. British Journal of Social Work. 2011;41:520–38. [Google Scholar]

- Burris E. R., Detert J. R., Chiaburu D. S. Quitting before leaving: The mediating effects of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008;93:912–22. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. Statutory social workers: Stress, job satisfaction, coping, social support and individual differences. British Journal of Social Work. 2008;38:1173–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cordes C. L., Dougherty T. W. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. The Academy of Management Review. 1993;18:621–56. [Google Scholar]

- Diestel S., Schmidt K. H. Direct and interaction effects among the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: Results from two German longitudinal samples. International Journal of Stress Management. 2010;17:159–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dobreva-Martinova T., Villeneuve M., Strickland L., Matheson K. Occupational role stress in the Canadian forces: Its association with individual and organizational well-being. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2002;34(2):111–21. [Google Scholar]

- Evans S., Huxley P., Gately C., Webber M., Mears A., Pajak S., Medina J., Kendall T., Katona C. Mental health, burnout, and job satisfaction among mental health social workers in England and Wales. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:75–80. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. The state of the global workplace: A worldwide study of employee engagement and wellbeing. 2010. available online at www.gallup.com/strategicconsulting/157196/state-global-workplace.aspx .

- Greenhaus J. H., Beutell N. J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10(1):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Griffeth R. W., Hom P. W., Gaertner S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management. 2000;26(3):463–88. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben J. R. B., Buckley M. R. Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management. 2004;30:859–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K., Cohen-Callow A., Kim H., Hwang J. Beyond intent to leave: Using multiple outcome measures for assessing turnover in child welfare. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(10):1380–7. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office. World Labor Report 1993. Geneva: International Labour Office; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. L., Wolfe D. M., Quinn R., Snoek J. D., Rosenthal R. A. Organizational Stress. New York: Wiley; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell R. E., Robie C. Withholding effort in organizations: Toward development and validation of a measure. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2003;17:537–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Job conditions, unmet expectations, and burnout in public child welfare workers: How different from other social workers? Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(2):358–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Ji J. Factor structure and longitudinal invariance of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19:325–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Stoner M. Burnout and turnover intention among social workers: Effects of role stress, job autonomy, and social support. Administration in Social Work. 2008;32:5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 3rd edn. New York: The Guildford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger J., Killham E. Who's driving innovation at your company? Gallup. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Lambert E. G., Pasupuleti S., Cluse-Tolar T., Jennings M., Baker D. The impact of work–family conflict on social work and human service worker job satisfaction and organizational commitment: An exploratory study. Administration in Social Work. 2006;30(3):55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. T., Ashforth B. E. The meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1996;81:123–33. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R. J., Rubin D. B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lizano E. L., Mor Barak M. E. Workplace demands and resources as antecedents of job burnout among public child welfare workers: A longitudinal study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(9):1769–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C., King R., Chenoweth L. Social work, stress, and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health. 2002;11:255–65. [Google Scholar]

- Louis R. B., Lepine J. A., Crawford E. R. Job engagement: Antecedent and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2010;53:617–35. [Google Scholar]

- Markos S., Sridevi S. M. Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business and Management. 2010;5:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. A multidimensional theory of burnout. In: Cooper C. L., editor. Theories of Organizational Stress. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:189–92. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Understanding burnout: Work and family issues. In: Halpern D. E., Murphy S. E., editors. From work-family balance to work–family interaction: Changing the metaphor. Mahwah, NJ: Lawerence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Understanding job burnout. In: Rossi A. M., Perrewe P. L., Sauter S. L., editors. Stress and Quality of Working Life: Current Perspectives in Occupational Health. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Jackson S. E. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour. 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Jackson S. E., Leiter M. P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd edn. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Schaufeli W. B., Leiter M. P. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel J. S., Kotrba L. M., Mitchelson J. K., Clark M. A., Baltes B. B. Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2011;32:689–725. [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Marín J., García-Campayo J., Mosquera Mera D., Lopez del Hoyo Y. A new definition of burnout syndrome based on Farber's proposal. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology. 2009;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor Barak M. E., Nissly J. A., Levin A. Antecedents to retention and turnover among child welfare, social work, and other human service employees: What can we learn from past research? A review and meta-analysis. Social Service Review. 2001;75(4):625–61. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) 1999. ‘Stress … at work’, Publication No. 99–101, available online at www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/99-101/pdfs/99-101.pdf .

- Naus F., Iterson A., Roe R. ‘Organizational cynicism: Extending the exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect model of employees’ responses to adverse conditions in the workplace'. Human Relations. 2007;60:683–718. [Google Scholar]

- Ng T. W. H., Feldman D. C. Age, work experience, and the psychological contract. Journal Organizational Behavior. 2009;30:1053–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ng T. W. H., Feldman D. C. Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2012;33:216–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nissly J. A., Mor Barak M. E., Levin A. Stress, social support, and workers' intentions to leave their jobs in public child welfare. Administration in Social Work. 2005;29(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Örtqvist D., Wincent J. Prominent consequences of role stress: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Stress Management. 2006;13:399–422. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters M. C. W., Montgomery A. J., Bakker A. B., Schaufeli W. B. Balancing work and home: How job and home demands are related to burnout. International Journal of Stress Management. 2005;12:43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Regehr C., Hemsworth D., Leslie B., Howe P., Chau S. Predictors of post-traumatic distress in child welfare workers: A linear structural equation model. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26(4):331–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo J. R., House R. J., Lirtzman S. I. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1970;15:150–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D. B. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1996;91:473–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rupert P. A., Stevanovic P., Hunley H. A. Work–family conflict and burnout among practicing psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult C. E., Farrel D., Rogers G., Mainous A. G. Impact of exchange variables on exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect: An integrative model of responses to declining job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal. 1988;31:599–627. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. L., Graham J. W. Missing data: Our view of state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;2:147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W. B., Leiter M. P., Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Development International. 2009;14:204–20. [Google Scholar]

- Simona G., Shirom A., Fried Y., Cooper C. A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology. 2008;61:227–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sprang G., Craig C., Clark J. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in child welfare workers: A comparative analysis of occupational distress across professional groups. Child Welfare. 2011;90(6):149–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalker C. A., Mandell D., Frensch K. M., Harvey C., Wright M. Child welfare workers who are exhausted yet satisfied with their jobs: How do they do it? Child & Family Social Work. 2007;12:182–91. [Google Scholar]

- Swider B. W., Zimmerman R. D. Born to burnout: A meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2010;76(3):487–506. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B. G., Fidell L. S. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tetrick L. E. Mediating effect of perceived role stress: A confirmatory analysis. In: Murphy L. R., Hurrell J. J. Jr, Quick J. C., editors. Stress and Well-Being at Work: Assessments and Interventions for Occupational Mental Health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1992. pp. 134–52. [Google Scholar]

- Travis D. J., Mor Barak M. E. Fight or flight? Factors impacting child welfare workers' propensity to seek positive change or disengage at work. Journal of Social Service Research. 2010;36(3):188–205. [Google Scholar]

- Travis D. J., Gomez R. J., Mor Barak M. E. Speaking up and stepping back: Examining the link between employee voice and job neglect. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(10):1831–41. [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. S., Konrad T. R., Scheckler W. E., Pathman D. E., Linzer M., McMurray J. E., Gerrity M., Schwartz M. Understanding physicians' intentions to withdraw from practice: The role of job satisfaction, job stress, mental and physical health. In: Friedman L. H., Goes J., Savage G. T., editors. Advances in Health Care Management. Vol. 2. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withey M. J., Cooper W. H. Predicting exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1989;34:521–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnik J. L., DePanfilis D., Daining C., McDermott Lane M. Factors Influencing Retention of Child Welfare Staff: A Systemic Review of Research. Washington, DC: Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]