Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder. The lungs are the principal organs affected, however, extrapulmonary involvement including disorders of the pituitary and thyroid glands has been reported but presentation with multiple endocrine manifestations is rare. We report the case of a 36-year-old African-American woman who presented with hypercalcaemia, abnormal thyroid function studies and secondary amenorrhoea. On workup including laboratory, radiological testing and biopsy she was diagnosed with sarcoidosis with multi-organ involvement. Endocrine manifestations included non-parathyroid hormone mediated hypercalcaemia related to sarcoidosis, thyroid involvement with sarcoidosis and hypothalamic–pituitary involvement with a sellar and suprasellar mass associated with secondary adrenal insufficiency, secondary hypogonadism, growth hormone deficiency and secondary hypothyroidism. We report to the best of our knowledge the first case of simultaneous multiple endocrine manifestations of sarcoidosis that included hypercalcaemia, hypopituitarism and sarcoidosis of the thyroid gland.

Background

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease; it is an immune syndrome resulting from various combinations of predisposing genetic, ethnic and environmental factors. It is characterised histologically by non-caseating granulomas that predominantly affect the lungs. However, it can also affect extrapulmonary organs including the lymph nodes, skin, eyes, cardiac, nervous system and others. The histological hallmark of non-caseating granulomas is however non-specific. Even though the exact mechanism is still to be elucidated, most recent studies have shown a relationship with helper T cell-mediated immune response to foreign or self-antigens in a genetically predisposed host. The diagnosis can be challenging due to multiple organ involvement and a wide variety of presentations that can mimic a multitude of other diseases. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on suggestive clinical and radiological findings, along with histological evidence of non-caseating granulomas on biopsy in the absence of any organisms or particles. In a patient presenting with Lofgren's syndrome (erythema nodosum, hilar adenopathy and polyarthralgia) a probable diagnosis can be made without biopsy but all other cases would require a biopsy from the most accessible organ.1 ACE levels have poor sensitivity for diagnosis and is likely more helpful for following disease course in those in whom it was initially elevated.2

Case presentation

A 36-year-old African-American woman with no significant medical history presented to our emergency department for hypercalcaemia, acute renal failure and an undetectable thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). She reported of generalised weakness, dizziness, weight loss of 45 lb over the past 6 months, headaches, polyuria, polydipsia, dysphagia, constipation, depression, labile mood and secondary amenorrhoea with her last menstrual cycle occurring 7 months earlier. She reported a surgical history of a tubal ligation and family history of unknown thyroid disease.

Her vital signs were significant for hypotension with a blood pressure of 98/67 mm Hg and tachycardia with a heart rate of 112 bpm. She had clinical signs of dehydration with dry mucous membranes and decreased skin turgor. Laboratory tests on presentation showed hypercalcaemia with albumin-corrected total calcium of 12.3 mg/dL (8.5–10.1), acute kidney injury with creatinine 2.5 mg/dL (0.6–1.3, baseline creatine 1 mg/dL), suppressed parathyroid hormone (PTH) 9 pg/mL (12.4–76.8), undetectable TSH<0.01 µIU/mL (0.36–3.74), free T3 2.56 pg/mL (2.18–3.98) and free T4 1.24 ng/dL (0.76–1.46). She had a negative pregnancy test.

The patient was admitted to the internal medicine service and started on aggressive intravenous fluids with normal saline. The endocrinology department was consulted to assist with the management of non-PTH-mediated hypercalcaemia, low TSH and a history of secondary amenorrhoea.

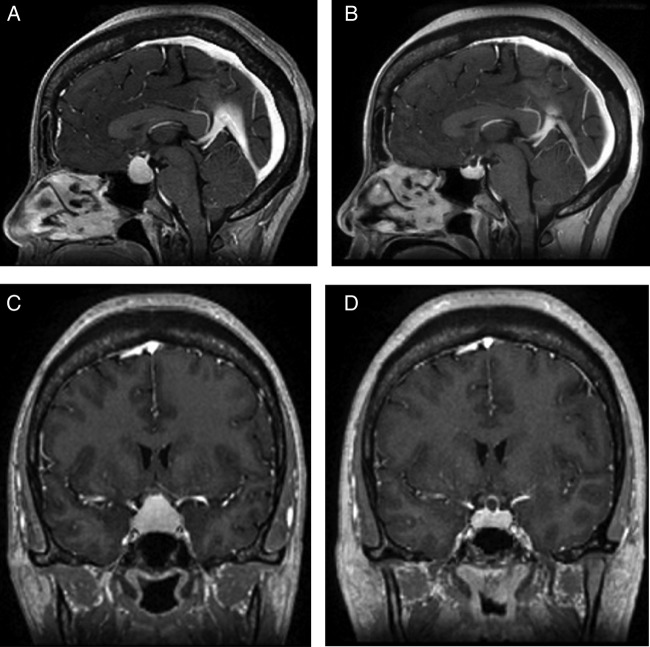

Chest X-ray was negative for any cardiopulmonary process or any hilar adenopathy. Ultrasound scan of the thyroid gland showed three solid isoechoic nodules within the right lobe of the thyroid ∼1 cm in diameter each, a 3.3×1.4 cm extrathyroidal mass in the right lateral neck as well as 1 cm right supraclavicular mass with multiple small masses in the left supraclavicular region. CT scan of the neck and chest without intravenous contrast showed extensive cervical and superior mediastinal nodularity. A CT scan of the head without intravenous contrast showed a 13 mm central skull base suprasellar mass. An MRI of the brain with and without intravenous contrast revealed a prominent 1.7×2.3 cm sellar and suprasellar mass with pituitary stalk thickening suggestive of an infiltrative disease process with upward displacement of optic chiasm (figure 1A– D). She did not have any visual field deficits by confrontation examination.

Figure 1.

MRI of the brain. Sagittal view (A) on initial presentation and (B) after 6 months of treatment with prednisone. Coronal view (C) on initial presentation and (D) after 6 months of treatment with prednisone.

The 25-OH vitamin D level was insufficient at 23.57 ng/mL (30–100) and the 1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D level was elevated at 107 pg/mL (19.9–79.3) suggesting 1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D-mediated hypercalcaemia. She had a normal glycated haemoglobin. Pituitary function workup showed elevated prolactin of 42.2 ng/mL (0.7–35.5) and a low insulin growth factor (IGF)-1 of 47 ng/mL (53–331). Luteinizing hormone of <0.2 mIU/mL and follicle-stimulating hormone of 4.3 mIU/mL were inappropriately low for oestradiol of <0.1 pg/mL consistent with secondary hypogonadism. The α subunit was normal. The patient subsequently underwent cosyntropin stimulation test with decreased cortisol response. Her baseline cortisol was 1.7 µg/dL with an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) of 10 pg/mL (6–48). Her peak cortisol response at 60 min was 10.3 µg/dL consistent with a diagnosis of central adrenal insufficiency. Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin and thyroid peroxidase antibody were both negative. Parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrp) and ACE levels were normal. With resolution of her acute kidney injury, her prolactin level returned to normal. There was no evidence of diabetes insipidus.

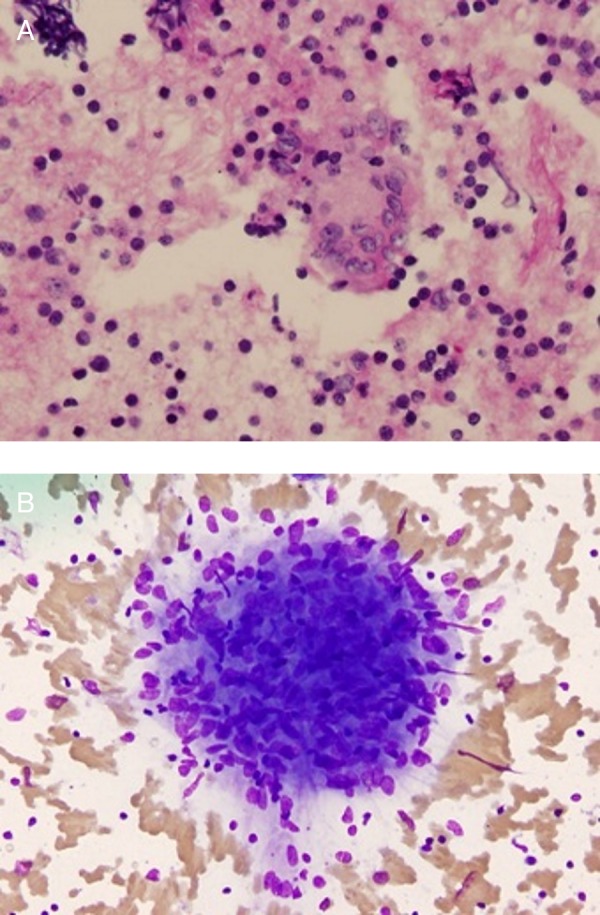

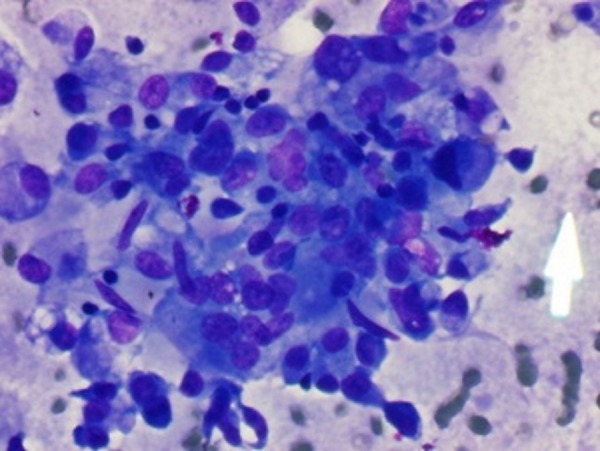

The patient had an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the right neck mass and the right thyroid nodule. The right neck mass showed a heterogeneous population of lymphocytes comprised of large and small lymphocytes in a background of lymphohistiocytic aggregates and non-caseating epithelioid granulomas confirming sarcoidosis in right cervical neck lymph node (figure 2A, B). The right thyroid nodule FNA demonstrated granuloma formation along with thyroid follicular cells confirming involvement with sarcoidosis (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cytology from fine needle aspiration of the right cervical lymph node. (A) Periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for any fungal element. (B) Aggregate of macrophages was consistent with granuloma.

Figure 3.

Fine needle aspiration from the thyroid nodule showing granulomatous formation with thyroid follicular cells.

The acute kidney injury and hypercalcaemia improved with intravenous fluids. A clinical diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made with endocrine manifestations of hypercalcaemia related to sarcoidosis, a sellar/suprasellar mass with hypopituitarism comprising central adrenal insufficiency, growth hormone deficiency and hypogonadism. The patient was started on prednisone, 60 mg daily with improvement in headaches.

A 123-I thyroid scan with uptake showed a very low 24 uptake of 1.3% suggestive of either destructive thyroiditis or central hypothyroidism.

Outcome and follow-up

One month after discharge repeat thyroid function testing confirmed hypothyroidism of central aetiology and the patient was started on levothyroxine replacement. The prednisone dose was tapered slowly as her headaches continued to improve. An MRI brain repeated 6 months after initiating treatment with prednisone showed a 50% decrease in the size of the sellar/suprasellar mass. She continues to have central adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism and hypogonadism.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease which typically presents with pulmonary manifestations but can involve any organ and tissue with a wide variety of clinical manifestations depending on the affected tissue and mimicking different diseases. A study of 1779 patients to evaluate comorbidities accompanying sarcoidosis showed almost 80% were diagnosed with pulmonary and/or lymph node involvement. Sarcoidosis of other sites was present in about 16% of patients.3 To the best of our knowledge this is the first report that demonstrated three endocrine-related manifestations of sarcoidosis that included pituitary and thyroid infiltration, as well as hypercalcaemia mediated by 1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D.

Hypercalcaemia occurs in ∼10–13% of patients with sarcoidosis with hypercalciuria being a more common manifestation in about one-third of patients.4 Hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria can occur anytime during the course of sarcoidosis and there can be exacerbation in summer months due to increased exposure to sunlight and resultant increase in vitamin D stores. The underlying mechanism is independent of PTH and has been shown to be caused by endogenous overproduction of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D by activated macrophages in granulomas,5 resulting in increased intestinal calcium absorption. Abnormal calcium metabolism by increased intestinal calcium absorption and increased bone turnover has also been demonstrated in sarcoidosis with normal calcium levels.6 Therefore, caution should be used with vitamin D replacement in patients with underlying sarcoidosis so as to not precipitate or worsen hypercalcaemia and/or hypercalciuria.

Neurosarcoidosis should be considered in patients with a known diagnosis of sarcoidosis who develop neurological complications. Some patients who present with neurosarcoidosis may not have any systemic features of the disease.

Hypothalamic–pituitary sarcoidosis can present with anterior hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus and hyperprolactinaemia. Imaging studies are usually characterised by sellar/suprasellar masses with or without pituitary stalk thickening. Hypothalamic and pituitary sarcoid involvement appears to be more common in men as opposed to other manifestations of sarcoidosis which have a female predilection.7 Earlier postmortem studies of patients with sarcoidosis complicated by hypopituitarism assumed that the hormone deficiency was due to pituitary gland destruction by granuloma formation,8 but subsequent studies showed responsiveness of pituitary gland to synthetic hypothalamic releasing factors suggesting that hypothalamic insufficiency may be the major cause of hypopituitarism in these patients.9

Hypogonadism appears to be the most common hormone deficiency associated with hypothalamic pituitary sarcoidosis.7 10 11 In a study of nine patients with hypothalamic–pituitary sarcoidosis, hypogonadism occurred in all the patients, diabetes insipidus in seven patients and hyperprolactinaemia in three patients.10 In a multicentre study of 24 patients, hypothalamic–pituitary sarcoidosis preceded the diagnosis of sarcoidosis in about half of the patients and occurred after diagnosis in others. Hypogonadism was the most common feature followed by TSH deficiency and hyperprolactinaemia, whereas diabetes insipidus occurred in half of the patients.11 There was no correlation of imaging with the pituitary hormone deficiency found and even though glucocorticoid treatment improved imaging abnormalities, it rarely resulted in resolution of the pituitary hormone deficiencies.7 10 11

Involvement of the thyroid gland with sarcoidosis is rare. In 1938, the first case was reported in a patient with systemic sarcoidosis at the time of postmortem examination.12 A 1–4% prevalence has been reported in autopsy studies of patients with systemic sarcoidosis.13 14 The diagnosis of thyroid sarcoidosis may be missed by FNA. Hoang et al reported a case of a non-toxic multinodular goitre with compressive symptoms as the initial presentation of systemic sarcoidosis. Initial FNA showed changes consistent with benign adenomatoid goitre. This was followed by total thyroidectomy which on histopathology showed numerous diffuse non-caseating granulomata in both lobes prompting workup and confirmation of systemic sarcoidosis.15

Caution is needed in patients with history of cancer, as sarcoidosis can mimic recurrence or metastatic cancer and these lesions will need biopsy and histopathological confirmation to establish a definitive diagnosis.16 Cervical lymphadenopathy in patients with sarcoidosis and papillary thyroid cancer can present a diagnostic dilemma. These patients would need a thorough evaluation and likely require a biopsy of the affected tissue.17 Lebo et al reported a patient who had a total thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid cancer and false-positive Tc-99m pertechnetate uptake in cervical lymph nodes on pre-radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy scan. This led to a lateral neck dissection but surgical pathology was negative for malignancy and showed granulomas typical of sarcoidosis.18

Learning points.

We report to the best of our knowledge, the first case of simultaneous multiple endocrine manifestations of sarcoidosis that include hypercalcaemia, hypopituitarism and sarcoidosis of the thyroid gland.

In conclusion, sarcoidosis is a multi-organ disease that can affect any organ and tissue and can mimic many other diseases making the diagnosis challenging. It should be considered in patients with multi-organ disease manifestations in the appropriate clinical setting.

Footnotes

Contributors: Planning for the manuscript was performed by the attending physician HK. Literature review and drafting of the manuscript was performed by NA and DB, and supervised by HK. The draft was finalised by all the authors. All the authors are in agreement with the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA 2011;305:391–9. 10.1001/jama.2011.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeRemee RA, Rohrbach MS. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme activity in evaluating the clinical course of sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med 1980;92:361–5. 10.7326/0003-4819-92-3-361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martusewicz-Boros MM, Boros PW, Wiatr E et al. . What comorbidities accompany sarcoidosis? A large cohort (n=1779) patients analysis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2015;32:115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma OP, Vucinic V. Sarcoidosis of the thyroid and kidneys and calcium metabolism. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2002;23:579–88. 10.1055/s-2002-36521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams JS, Gacad MA, Singer FR et al. . Production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by pulmonary alveolar macrophages from patients with sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986;465:587–94. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb18535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiner M, Sigurdsson G, Nunziata V et al. . Abnormal calcium metabolism in normocalcaemic sarcoidosis. BMJ 1976;2:1473–6. 10.1136/bmj.2.6050.1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anthony J, Esper GJ, Ioachimescu A. Hypothalamic-pituitary sarcoidosis with vision loss and hypopituitarism: case series and literature review. Pituitary 2016;19:19–29. 10.1007/s11102-015-0678-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleisch VR, Robbins SL. Sarcoid-like granulomata of the pituitary gland; a cause of pituitary insufficiency. AMA Arch Intern Med 1952;89:877–92. 10.1001/archinte.1952.00240060020003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuart CA, Neelon FA, Lebovitz HE. Hypothalamic insufficiency: the cause of hypopituitarism in sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med 1978;88:589–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-88-5-589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bihan H, Christozova V, Dumas JL et al. . Sarcoidosis: clinical, hormonal, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) manifestations of hypothalamic-pituitary disease in 9 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:259–68. 10.1097/MD.0b013e31815585aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langrand C, Bihan H, Raverot G et al. . Hypothalamo-pituitary sarcoidosis: a multicenter study of 24 patients. QJM 2012;105:981–95. 10.1093/qjmed/hcs121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer J, Warren S. Boeck's sarcoid: report of a case with clinical diagnosis confirmed at autopsy. Arch Intern Med 1938;62:285–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vailati A, Marena C, Aristia L et al. . Sarcoidosis of the thyroid: report of a case and a review of the literature. Sarcoidosis 1993;10:66–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayock RL, Bertrand P, Morrison CE et al. . Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am J Med 1963;35:67–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoang TD, Mai VQ, Clyde PW et al. . Multinodular goiter as the initial presentation of systemic sarcoidosis: limitation of fine-needle biopsy. Respir Care 2011;56:1029–32. 10.4187/respcare.01000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myint ZW, Chow RD. Sarcoidosis mimicking metastatic thyroid cancer following radioactive iodine therapy. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2015;5:26360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ergin AB, Nasr CE. Thyroid cancer & sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2014;31:239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lebo NL, Raymond F, Odell MJ. Selectively false-positive radionuclide scan in a patient with sarcoidosis and papillary thyroid cancer: a case report and review of the literature. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;44:18 10.1186/s40463-015-0069-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]