ABSTRACT

Embryos from females homozygous for a recessive maternal-effect mutation in the gene aura exhibit defects including reduced cortical integrity, defective cortical granule (CG) release upon egg activation, failure to complete cytokinesis, and abnormal cell wound healing. We show that the cytokinesis defects are associated with aberrant cytoskeletal reorganization during furrow maturation, including abnormal F-actin enrichment and microtubule reorganization. Cortical F-actin prior to furrow formation fails to exhibit a normal transition into F-actin-rich arcs, and drug inhibition is consistent with aura function promoting F-actin polymerization and/or stabilization. In mutants, components of exocytic and endocytic vesicles, such as Vamp2, Clathrin and Dynamin, are sequestered in unreleased CGs, indicating a need for CG recycling in the normal redistribution of these factors. However, the exocytic targeting factor Rab11 is recruited to the furrow plane normally at the tip of bundling microtubules, suggesting an alternative anchoring mechanism independent of membrane recycling. A positional cloning approach indicates that the mutation in aura is associated with a truncation of Mid1 interacting protein 1 like (Mid1ip1l), previously identified as an interactor of the X-linked Opitz G/BBB syndrome gene product Mid1. A Cas9/CRISPR-induced mutant allele in mid1ip1l fails to complement the originally isolated aura maternal-effect mutation, confirming gene assignment. Mid1ip1l protein localizes to cortical F-actin aggregates, consistent with a direct role in cytoskeletal regulation. Our studies indicate that maternally provided aura (mid1ip1l) acts during the reorganization of the cytoskeleton at the egg-to-embryo transition and highlight the importance of cytoskeletal dynamics and membrane recycling during this developmental period.

KEY WORDS: Mid1, Mid1ip1l, Cytoskeleton, Cortical granules, Membrane exocytosis, Cytokinesis, F-actin, Zebrafish, Opitz G/BBB syndrome

Summary: The zebrafish maternal-effect gene aura encodes Mid1ip1l, which is involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements during the egg-to-embryo transition.

INTRODUCTION

The egg-to-embryo transition in the zebrafish involves multiple cytoskeletal changes, such as the reorganization of the egg cortex, ooplasmic streaming and the preparation of the cytoskeleton for cell division. The zebrafish egg cortex is composed of a meshwork of actin filaments (Hart and Collins, 1991; Becker and Hart, 1996). During oogenesis, membrane-bound cortical granules (CGs) accumulate throughout this egg cortex (Hart et al., 1987; Mei et al., 2009), and activation of the egg through water exposure triggers rapid granule exocytosis (Hart and Collins, 1991; Becker and Hart, 1999). Upon exocytosis, released CG products promote the lifting and hardening of the chorion (Wessel and Wong, 2009).

Inhibition or stabilization of the actin network leads to enhanced or reduced CG release, respectively, suggesting that the F-actin cytoskeleton acts as a physical barrier that needs to be remodeled and dismantled to allow for CG release. As CGs exocytose, membrane must be retrieved, presumably through a process such as Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Bement et al., 2000; Tsai et al., 2011), and indeed both Clathrin and Dynamin have been found to localize to at least a subset of CGs (Faire and Bonder, 1993; Kanagaraj et al., 2014). After exocytosis, F-actin undergoes rapid reassembly to enclose the edges of endocytosing crypts at sites of previous exocytotic events (Becker and Hart, 1999).

During embryonic cell division, the cytoskeleton is involved in the formation and resolution of cell boundaries between blastomeres (Rappaport, 1996). During furrow formation, zebrafish blastomeres form an F-actin-based contractile ring (Urven et al., 2006; Li et al., 2008; Webb et al., 2014), as well as pericleavage actin enrichments on both sides of the furrow, which converge to generate adhesive cell walls. The microtubule apparatus also undergoes stereotypic rearrangements during furrow formation (Jesuthasan, 1998; Urven et al., 2006). At the time of furrow initiation, microtubules derived from spindle asters reorganize into an array of bundles parallel to each other and perpendicular to the furrow, termed the furrow microtubule array (FMA) (Danilchik et al., 1998; Jesuthasan, 1998). As the furrow matures, FMA bundles become enriched at distal ends of the furrow while acquiring a characteristic tilting angle, pointing distally. Subsequently, distally located FMA bundles undergo disassembly.

Vesicular delivery of structural proteins and membrane is necessary to prevent the furrow from regressing (Danilchik et al., 1998, 2003; Jesuthasan, 1998; Pelegri et al., 1999), and microtubules act as substrates for the trafficking of Rab11-positive vesicles to the membrane (Takahashi et al., 2012). In the early zebrafish embryo, SNARE-mediated vesicle fusion required for membrane remodeling during cytokinesis relies on microtubules of the FMA and pericleavage F-actin enrichments (Li et al., 2006).

Here, we characterize the role of aura in early embryonic development, in processes that include plasma membrane integrity and CG release after egg activation, cell wound healing and cytokinesis. We show that aura encodes Mid1ip1l, a maternally provided zebrafish homolog of Mid1 interacting protein 1 (Mid1ip1), a protein that interacts with Mid1, which in humans is the product of the X-linked Opitz G/BBB syndrome causal gene. Our studies indicate a role for maternal aura (mid1ip1l) in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton at the egg-to-embryo transition, and highlight the importance of cytoskeletal dynamics and membrane recycling for early embryonic development.

RESULTS

Effects of a mutation in aura at the egg-to-embryo transition

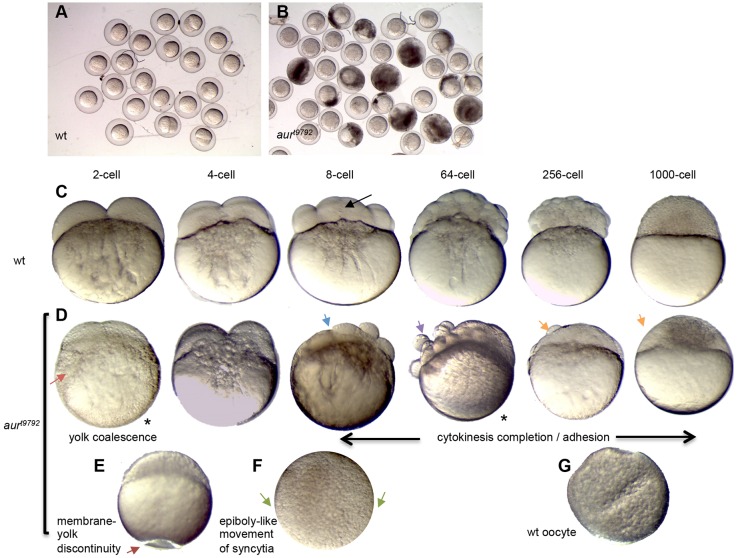

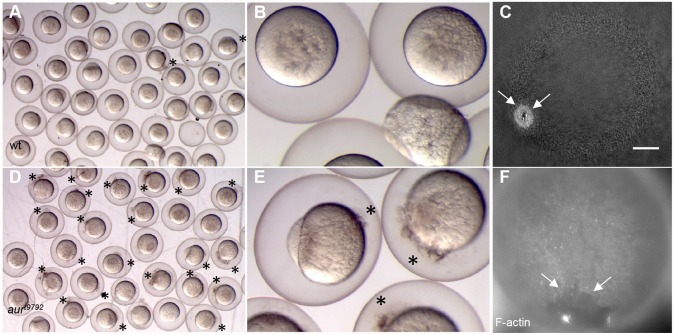

Embryos from females homozygous for a mutation in aura, for simplicity referred to here as aura mutants, exhibit complete embryonic lethality due to a variety of defects (Pelegri et al., 2004) (Fig. 1, Fig. S1A,B). In the most severely affected clutches, a significant fraction of embryos or activated eggs undergo lysis immediately after laying (Fig. 1A,B), suggesting a defect in egg membrane integrity. In eggs that do not undergo lysis, aura mutants typically exhibit abnormal yolk morphology. In wild type, the yolk is present as discrete granules in the mature egg (Fig. 1G), which coalesce during egg activation (Fig. 1C, 2-cell). In aura mutants, the yolk resembles that in the mature oocyte (Fig. 1D, 2-cell), suggesting a defect in yolk coalescence. In addition, aura mutant eggs and embryos often show pockets of ooplasm trapped between membrane and an indented yolk cortex (Fig. 1E, arrow). Blastodisc lifting, a result of ooplasmic streaming during the first few cell cycles (Hisaoka and Firlit, 1960; Leung et al., 2000; Fernández et al., 2006; Fuentes and Fernández, 2010), is mildly reduced in aura mutants (Fig. S2A,B). aura mutants also exhibit a mild reduction in chorion expansion and integrity during the first cell cycle (Fig. S2C-E, see below). During oogenesis, yolk granule and CG distribution (Fig. S2F-I), as well as enrichment of F-actin and formation of the mitochondrial cloud (Marlow and Mullins, 2008; Gupta et al., 2010), appear normal (Fig. S3A-D).

Fig. 1.

Developmental timecourse of zebrafish aura mutant embryos. (A,B) Embryo clutches from wild-type (A) and aura mutant (B) mothers at 10 mpf showing egg lysis in mutants. (C-G) Wild-type (C,G) and aura mutant (D-F) timecourse. aura embryos do not display normal yolk coalescence (red arrow), instead resembling inactive wild-type mature oocytes (G). At the 8-cell stage, a septum is apparent in wild type (black arrow), whereas aura mutants lack this septum (blue arrow). aura mutants subsequently exhibit rounded, non-adhesive cells (purple arrow). In the cleavage stages, aura mutant embryos are partially or fully syncytial (orange arrows). Other phenotypes include discontinuities between the egg plasma membrane and the yolk along any animal-vegetal position (E, dark red arrow). Syncytia in aura mutants undergo an epiboly-like movement (F, green arrows indicate migrating edge).

Fertilized aura mutant embryos exhibit defective cell division. In wild type, the region between the two central blastomeres (corresponding to the furrow for the first cell cycle) exhibits, by the 8-cell stage, a clearly visible membrane septum (Fig. 1C, 8-cell), which contributes to cell-cell adhesion. In aura mutants, furrows ingress normally, generating a normal cleavage pattern (Fig. 1D, 4-cell; Fig. S3E,F). However, at a time corresponding to the 8-cell stage, when the furrow for the first cell cycle should have undergone completion, aura mutants display no clearly defined septum and instead exhibit either the initial rounded morphology corresponding to the ingressing blastomeres or regress (Fig. 1D, 8-cell; Fig. S3G,H).

At a time when wild-type embryos are forming a cellularized blastula, aura mutants contain irregularly sized blastomeres and rounded cells at the surface (Fig. 1, 64-cell; Fig. S3G,H). When wild-type embryos display a mass of cells on top of the yolk at the 512-cell and 1000-cell stages (Fig. 1C), aura mutants are either fully syncytial or display pockets of cells aggregated atop a syncytial region (Fig. 1D, 256-cell and 1000-cell), resembling other cell division mutants (Pelegri et al., 1999; Dosch et al., 2004; Yabe et al., 2009). At a time coincident with the initiation of epiboly in wild type, the syncytial mass in aura mutants expands downward over the yolk (Fig. 1F, Fig. S3I-L), and mutants typically undergo lysis by 4-10 h post fertilization (hpf).

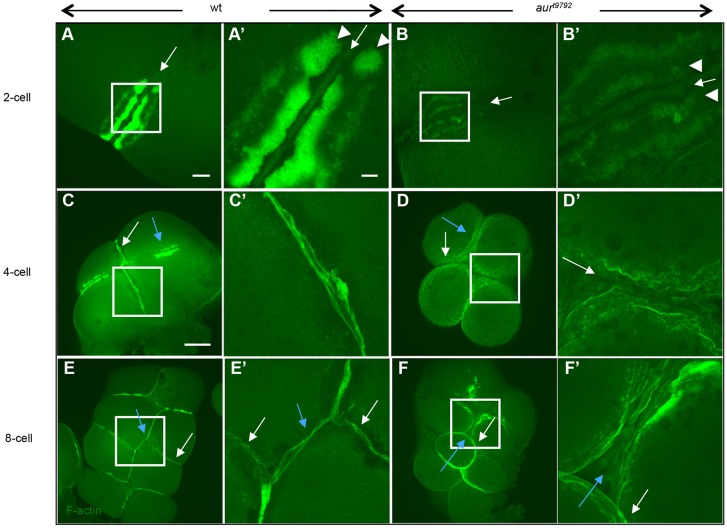

Maternal aura function is essential for furrow maturation during late cytokinesis

During development of the first furrow, F-actin is recruited to form the contractile ring (Fig. 2A,A′, arrow). In addition, wild-type zebrafish embryos show accumulation of pericleavage F-actin along the furrow (Fig. 2A,A′, arrowheads). As the furrow matures, pericleavage F-actin forms lamella-like structures that converge at the furrow center to form an adhesive cell wall (Fig. 2C,C′). This process is repeated in subsequent cell cycles (Fig. 2E,E′). In aura mutants during furrow initiation (Fig. 2B,B′), F-actin accumulations occur in the contractile ring (arrow) and pericleavage (arrowheads) regions, although the level of F-actin in pericleavage regions appears reduced (Fig. 2B,B′). During furrow maturation in mutants, pericleavage F-actin does not converge or form an adhesive wall (Fig. 2D,D′), and lack of blastomere coherence becomes apparent by the third cell cycle (Fig. 2F,F′, Fig. S3H).

Fig. 2.

aura mutant embryos exhibit reduced accumulation of pericleavage and adhesive junction F-actin. (A,A′) In wild type (25/25), F-actin becomes recruited to the contractile ring (arrows) and pericleavage regions (arrowheads). (B,B′) In aura mutants, the contractile ring pericleavage F-actin is reduced (30/30). (C,C′) At the 4-cell stage, the furrow corresponding to the first cell cycle has formed adhesion junctions containing F-actin (white arrow). (D,D′) At the same stage, aura embryos do not exhibit adhesion junction F-actin cables (white arrow). (E-F′) Defects continue to be observed in subsequent furrows. White and blue arrows indicate furrows for the first and second cell cycles, respectively. (A′-F′) Higher magnification views of boxed regions in A-F. Scale bars: 20 μm in A,B; 100 μm in C-F; 10 μm in A′-F′.

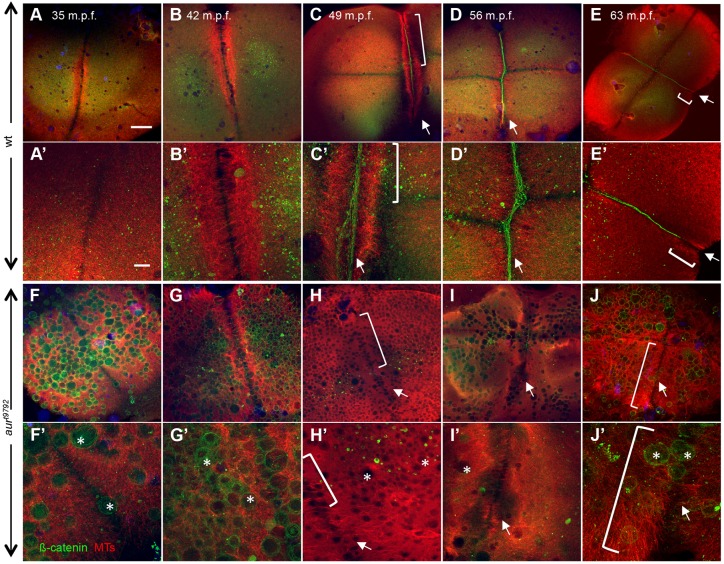

To better visualize cell adhesion junctions, we labeled wild-type and aura mutant embryos to detect β-Catenin (Fig. 3). The same embryos were additionally labeled to detect microtubules, which have a role in the exocytosis of vesicles containing cell adhesion junction components (Jesuthasan, 1998). In wild-type embryos, β-Catenin aggregates along the cleavage plane in mature furrows (Fig. 3C-E, arrows). By contrast, β-Catenin accumulation is severely reduced in aura mutant embryos (Fig. 3H-J, arrows). Surprisingly, in aura mutant embryos β-Catenin localizes to ectopic vesicles present throughout the blastocyst (Fig. 3F′-J′, asterisks; see below).

Fig. 3.

aura mutant embryos do not recruit cell adhesion components to furrows and exhibit aberrant furrow microtubule dynamics. (A-E) In wild-type (12/12), the FMA forms as tubules become arranged in a parallel fashion (A-B′). As the furrow matures, FMA tubules become tilted and accumulate at the furrow distal end (E,E′). During furrow maturation, cell adhesion components such as β-Catenin accumulate at the furrow (C-E). (F-J) In aura mutants, FMA tubules form (F-H, brackets in H,H′) but remain in a parallel array arrangement throughout the length of the furrow (J,J′, brackets), failing to aggregate at the furrow distal ends (assayed at 49-63 mpf; 15/15). All aura mutant embryos examined also fail to recruit β-Catenin to the furrow (H-J, arrows). Instead, β-Catenin localizes to ectopic CGs (F′-J′, asterisks). (A′-J′) Higher magnification views of A-J. Scale bars: 100 μm in A-J; 10 μm in A′-J′.

The labeled embryos also allowed us to detect potential defects in microtubule reorganization during cytokinesis. During furrow initiation, wild-type embryos organize the FMA as arrays of microtubules parallel to each other and perpendicular to the furrow (Danilchik et al., 1998; Jesuthasan, 1998; Pelegri et al., 1999; Urven et al., 2006) (Fig. 3A-D, bracket in C,C′; Fig. S4A, double arrows). As furrows mature, microtubules in these arrays progressively accumulate at the furrow distal ends and tilt their orientation to form V-shape structures pointing distally (Fig. 3E,E′, bracket; Fig. S4A, arrows). Subsequently, FMA tubules disassemble (Fig. S4A, arrowheads). In aura mutants, FMA microtubules appear to align relatively normally as arrays perpendicular to the furrow (Fig. 3F-I, brackets in H,H′; Fig. S4B, double arrows). However, during furrow maturation, FMA tubules in aura mutants maintain their original conformation perpendicular to the furrow and without any apparent bulk distal enrichment (Fig. 3J,J′, brackets; Fig. S4B, double arrows), until they eventually become undetectable (Fig. S4B, dashed double arrows). Although microtubule alignment can appear distorted in furrow regions that contain ectopic vesicles (Fig. 3F-I), defects in FMA reorganization can be detected regardless of the presence of ectopic vesicles (Fig. S4C,D). These observations suggest that aura is required for FMA reorganization.

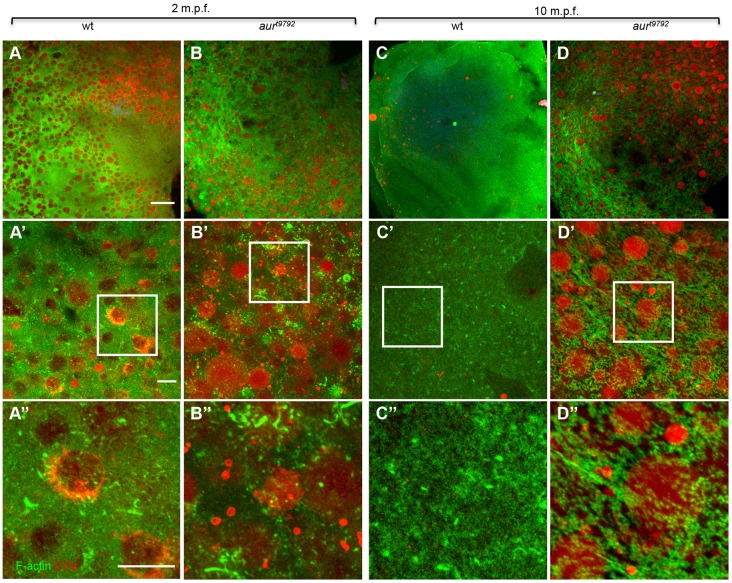

aura mutant embryos show defects in CG exocytosis

The size and the large number of vesicles observed in aura mutants suggested that they are unreleased CGs (Becker and Hart, 1999), which we confirmed using the glycoconjugate-binding dyes Maclura pomifera agglutinin (MPA) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (Becker and Hart, 1999; El-Mestrah and Kan, 2001; Bembenek et al., 2007). Quantification of CG densities in mature, extruded eggs from wild-type and aura mutant females indicates that initial CG densities are not significantly different (paired t-test, P=0.56). At 2 min post fertilization (mpf) (Becker and Hart, 1999), wild type and aura mutants still exhibit a similar density of CGs (Fig. 4A,B). In wild type, exocytosis of CGs leads to the complete or near complete absence of CGs by 10 mpf (Fig. 4C, 2.0% unreleased; see Materials and Methods). By contrast, at 10 mpf aura mutant embryos exhibit a significant number of unreleased CGs (Fig. 4D, 53% unreleased), which are observed in the most cortical 12 µm and with highest densities in the region immediately below the cortex (Fig. S5A-D; data not shown). These observations suggest that CGs accumulate normally in developing aura mutant oocytes but experience defective release upon egg activation. A reduction in CG exocytosis can also explain defects observed in chorion expansion and integrity (Fig. S2C-E) (Wessel and Wong, 2009).

Fig. 4.

aura mutants retain CGs. (A,B) During egg activation (2 mpf), CGs appear embedded in an F-actin network in both wild type (A) and aura mutants (B). (C,D) By 10 mpf, wild-type eggs have extruded nearly all CGs (C), whereas a large fraction of CGs are retained in aura mutants (D) (wild type, 0 mpf n=152, 10 mpf n=3; mutant, 0 mpf n=245, 10 mpf n=130; chi-square, P<0.0001). By 10 mpf, the cortical F-actin cytoskeleton appears as a network of short F-actin fibers in aura mutants (D″), in contrast to being largely disassembled as in wild type (C″). (A′-D′) Higher magnification views of A-D; the boxed regions are further magnified in A″-D″. Scale bars: 100 μm in A-D; 10 μm in A′-D′,A″-D″.

Previous studies have shown that, during oogenesis, CGs are embedded in an F-actin network and that CG release is dependent on F-actin dynamics (Becker and Hart, 1999). At 2 mpf, CGs appear similarly embedded in an F-actin network in both wild type and aura mutants (Fig. 4A,B, Fig. S5A,C). At 10 mpf, F-actin in wild type has undergone a dramatic rearrangement (Fig. 4C′,C″, Fig. S5B) and appears enriched in cortical puncta that are likely to correspond to remnants of exocytic events (Becker and Hart, 1999) (Fig. 4C′,C″). By contrast, unreleased CGs in aura mutants at 10 mpf appear encased in an F-actin network similar to that at earlier time points (Fig. 4D-D″, Fig. S5D). Our observations suggest that aura function is required for the dynamic F-actin reorganization necessary for CG release.

aura mutant embryos display defects in wound repair

The high frequency of lysed eggs found in severely affected aura mutants suggested that they might have a defect in wound repair. To test this, wild-type and aura mutant embryos were wounded by pricking the cell membrane with an injection needle at 10-15 mpf. At 30 mpf, nearly all pricked wild-type embryos had fully resealed their cell membranes (2% with wounds, n=150; Fig. 5A,B), whereas nearly all pricked aura mutant embryos continued to display signs of wounding (94%, n=243; Fig. 5D,E).

Fig. 5.

Wound healing defect in aura mutant embryos. (A,B,D,E) Embryos from wild-type (A,B) and aura mutant (D,E) mothers were pricked with a glass injection needle at 10-15 mpf and allowed to recover until 30 mpf. After recovery, most wild-type embryos have resealed their membrane, whereas a majority of aura mutant embryos show continued leakage of yolk and ooplasm (D,E, asterisks). (C,F) Wild-type (C) and aura mutant (F) embryos were fixed 1 min after wounding and labeled with phalloidin. Wild-type embryos recruit F-actin to the closing wound edge (C, arrows; 7/7). All aura embryos examined show reduced F-actin enrichment at the wound edge and a larger wound diameter (F, arrows; 13/13). Scale bar: 100 μm in C,F.

Previous studies have shown that wound healing of the embryo cell membrane is mediated by the recruitment and contraction of F-actin to the edge of the wound site (Bement et al., 1999; Mandato and Bement, 2001). We therefore fixed embryos 1 min after wounding and labeled them to detect F-actin. At this time point, wild-type embryos showed small diameter rings with high levels of F-actin at the wound edge (Fig. 5C). By contrast, similarly treated aura mutant embryos exhibited large diameter cortical openings with reduced levels of F-actin (Fig. 5F). These observations indicate that aura function is required for F-actin enrichment at sites of wound repair.

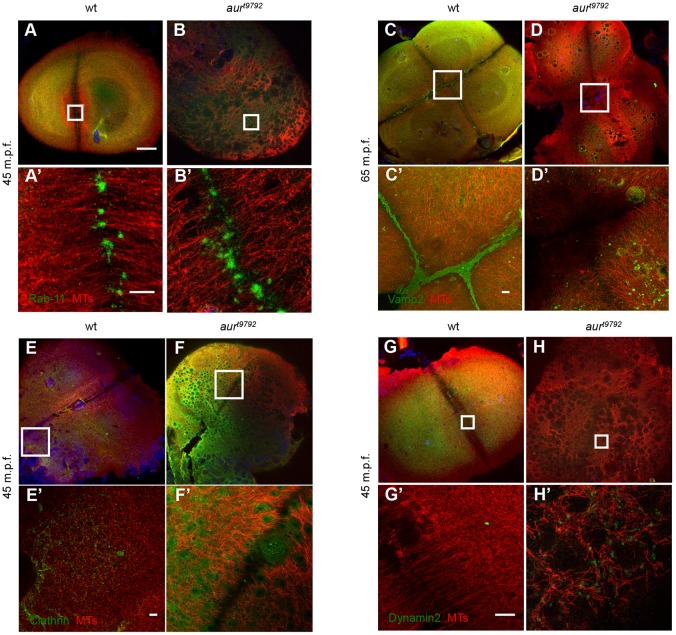

Distribution of exocytic and endocytic markers is affected in aura mutants

Dynamic membrane release and retrieval, two processes affected in aura mutant embryos, are known to be important in CG release (Bement et al., 2000), furrow maturation (Albertson et al., 2005, 2008; Li et al., 2006, 2008; Takahashi et al., 2012) and wound closure (McNeil, 2002; Togo and Steinhardt, 2004; Idone et al., 2008). This led us to characterize the distribution of exocytic and endocytic markers in aura mutants. Rab11, a GTPase involved in the docking and fusion of vesicles during exocytosis (Takahashi et al., 2012) required for cytokinesis completion (Pelissier et al., 2003; Giansanti et al., 2007), accumulates at the tips of bundling FMA tubules in wild-type embryos (Fig. 6A,A′), and this accumulation is normal in aura mutants (Fig. 6B,B′). By contrast, the localization of Vamp2, a marker for docking and/or fusion of membrane vesicles (Conner et al., 1997; Li et al., 2006), is severely affected in aura mutants. In wild-type embryos, Vamp2 accumulates along the plane of the mature furrow (Li et al., 2006) (Fig. 6C,C′, Fig. S5E,E′). In aura mutants, Vamp2 instead localizes to the surface of ectopic vesicles corresponding to unreleased CGs (Fig. 6D,D′, Fig. S5F,F′). Thus, some but not all steps in vesicle exocytosis are dependent on aura function.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of exocytic and endocytic factors in aura mutants. (A,B) The exocytic factor Rab11 properly localizes to the tips of microtubules at the furrow in wild-type (5/5) and aura mutant (6/6) embryos. (C,D) The exocytic factor Vamp2 localizes to mature furrows in wild type (5/5) but not in mutants (7/7). (E-H) The endocytic factors Clathrin and Dynamin 2 become enriched in ectopic CGs in aura mutants (F,F′,H,H′), whereas they exhibit a disperse cortical distribution in wild type (E,E′,G,G′). Clathrin appears localized to the CG surface in ectopic CGs in aura mutants (5/5 embryos, compared with 10/10 wild-type embryos with diffuse cortical labeling). Dynamin 2 also localizes to ectopic CGs (15/15 embryos, compared with 13/13 wild-type embryos with diffuse cortical labeling), which can appear as ring-like structures (3/15 embryos as shown in H′) or throughout the granule surface (12/15 embryos as shown in Fig. S5M,M′). Ectopic localization to CGs was confirmed by colabeling with WGA (not shown). (A′-H′) Higher magnifications of boxed regions in A-H. Scale bars: 100 μm in A-H; 10 μm in A′-H′.

We also analyzed the localization of two endocytic factors: Clathrin, which forms the lattice structure of endocytic coated-vesicles (Pearse, 1976; Royle, 2006); and Dynamin, a large GTPase that mediates their scission (Hinshaw, 2000). In wild type, these factors are diffusely distributed through the cortex (Fig. 6E,G), whereas in aura mutants Clathrin and Dynamin, like Vamp2, exhibit localization to ectopic CGs throughout the embryo (Fig. 6F,H). In the case of Clathrin, the labeling is relatively diffuse throughout the surface of the CG. Dynamin exhibits diffuse localization (Fig. S5M,N) but is also observed to form ring-like structures (Fig. 6H,H′) reminiscent of Dynamin-based rings described in other systems (Hinshaw, 2000). These data are consistent with previous studies that identify Clathrin and Dynamin as components of CGs in oocytes (Faire and Bonder, 1993; Tsai et al., 2011) (Fig. S5G,H).

Our results suggest that the defect in CG exocytosis that occurs during egg activation in aura mutants results in the sequestering of exocytic and endocytic factors.

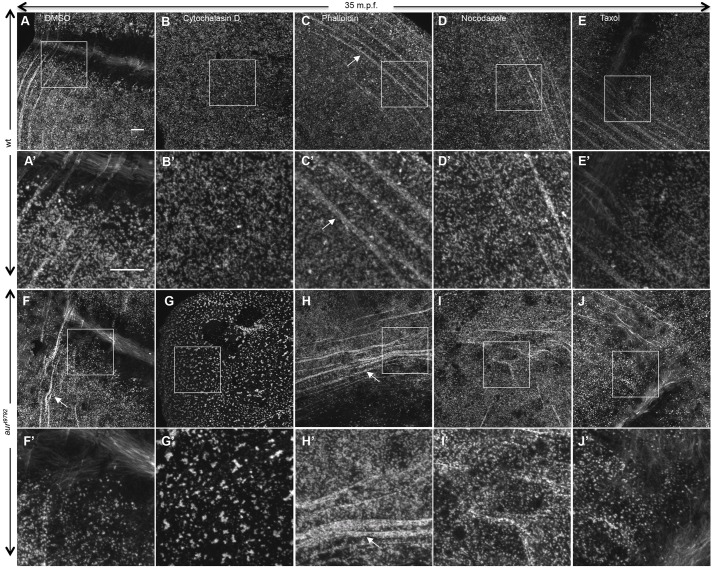

F-actin reorganization defects in aura mutants

To gain a better understanding of aura function we focused on cortical F-actin reorganization during the first cell cycle (Fig. 7), as this process is amenable to observation and drug treatment and occurs prior to furrow formation, facilitating interpretation of the phenotype. High-magnification views of F-actin in wild-type embryos during the period 5-35 mpf show that cortical F-actin transitions from an initial field of punctate structures at 5 mpf (Fig. 7A,A′), through transient association as aggregates at 10-20 mpf (Fig. 7B,B′,C,C′), to develop band-like structures consisting of F-actin aggregates (27-35 mpf; Fig. 7D,E,E′, arrows). These F-actin bands correspond to previously described circumferential F-actin arcs parallel to the outer rim of the blastodisc (Theusch et al., 2006; Nair et al., 2013b). At later stages (42-63 mpf), which coincide with the period of cytokinesis for the first cell cycle, the circumferential F-actin bands persist and a contractile band develops at the site of furrow formation (Fig. 2; data not shown). In aura mutants, the early cortical F-actin field appears punctate, as in wild type (Fig. 7F,F′). However, instead of undergoing the reorganization observed in wild type, in mutants the cortical F-actin develops into a fine meshwork (Fig. 7G,G′,H,H′). This meshwork gradually hollows, forming an increasing area of F-actin-free patches while the F-actin coalesces into lines of single aggregates (Fig. 7J′, arrowheads). Although F-actin bands can also be observed in aura mutants, these exhibit a less ordered orientation with respect to the blastodisc periphery and appear to be less continuous and composed of a smaller number of aggregates than in wild type (Fig. 7I, arrows). These trends continue at later stages (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

aura mutant embryos do not undergo dynamic actin rearrangement. (A-E) Wild-type embryos undergo dramatic actin rearrangement at the cortex leading to organized actin arcs (arrows), whereas aura mutant embryos fail in cortical actin rearrangement resulting in punctate F-actin aggregation (F-J, arrowheads). (A′-J′) Higher magnifications of boxed regions in A-J. At least three embryos were imaged per time point. Scale bars: 10 μm.

We also observed cortical F-actin in live wild type and mutants using the LifeAct transgene (Behrndt et al., 2012). This analysis revealed a dynamic wave-like pattern of cortical F-actin in wild type, which temporarily coalesces into F-actin bands (Movie 1). aura mutants failed to show this dynamic pattern, instead exhibiting the gradual aggregation detected in fixed embryos (Movie 2).

We additionally tested the effect of cytoskeletal dynamics inhibitors on the F-actin network of wild-type and mutant embryos (Fig. 8), in particular whether these drugs modify the phenotype normally observed in an untreated mutant (Fig. 8F,F′). Exposure to the F-actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D dramatically enhanced the aura cortical F-actin phenotype (Fig. 8G,G′). By contrast, exposure to the F-actin stabilizer phalloidin appeared to ameliorate the mutant F-actin phenotype (Fig. 8H,H′, arrows). Exposure to microtubule inhibiting (nocodazole) and stabilizing (taxol) drugs did not have major effects on the mutant F-actin phenotype (Fig. 8I,I′,J,J′).

Fig. 8.

The aura mutant phenotype is enhanced by actin polymerization inhibitor and ameliorated by actin stabilizer. In wild type, cytochalasin D leads to a lack of F-actin arcs (B,B′; 17/17) and phalloidin does not have an effect (C,C′; 23/23). In aura mutant embryos, cytochalasin D leads to strongly punctate F-actin (G,G′; 17/17), and phalloidin reverses the phenotype, stabilizing F-actin arcs (H,H′, arrows; 11/11). Microtubule inhibiting (nocodazole, D,D′,I,I′) and stabilizing (taxol, E,E′,J,J′) drugs do not change the dynamic F-actin reorganization in wild-type (16/16 and 15/15, respectively) or aura mutant (15/15 and 10/10, respectively) embryos. (A′-J′) Higher magnifications of boxed regions in A-J. Embryos are at 35 mpf. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Together, our observations are consistent with a role for aura in the dynamic rearrangement of cortical F-actin, possibly by promoting enhanced actin polymerization or stabilization.

aura encodes Mid1 interacting protein 1 like

We undertook a positional cloning approach to identify aura through bulk segregation analysis, using markers polymorphic between the AB/Tübingen strain that carries the aurt9792 mutation and the WIK strain, followed by fine mapping (see Materials and Methods). Analysis of key recombination events placed the mutation within a critical region containing nine predicted genes and identified a polymorphic marker fully linked to the mutation in 700 meioses (Fig. S6A). Sequencing of amplified genomic and cDNA products for genes closest to this marker identified an A-to-T transversion in the gene mid1 interacting protein 1 like (mid1ip1l). This sequence change converts a codon encoding lysine to a stop codon, causing truncation of the 24 C-terminal amino acids of Mid1ip1l (Fig. 9A,B). The C-terminal region truncated in the mutant aura allele deletes over half of a 45 amino acid block that is highly conserved in Mid1ip1 homologs found in various organisms, including human, mouse, frog and chicken (Fig. 9C). Protein prediction analysis (PredictProtein) suggests that this mutation occurs within the last helical structure of Mid1ip1l, and mutation-effect predictions (SuSPect) suggest that its truncation would have severe effects on protein function (Fig. S6B).

Fig. 9.

aura encodes Mid1ip1l. (A) Mid1ip1l protein in wild-type and aura mutant alleles. Red boxes indicate predicted alpha helices. The aurt9792 mutation generates a premature stop that truncates the last conserved helix. The CRISPR/Cas9-generated mid1ip1luw39 allele results in a frameshift translated region (dark red box) followed by an early stop. (B) DNA sequencing trace of the aurt9792 allele, which creates a stop codon in amino acid 142. (C) Amino acid sequence comparison between various mid1ip1 homologs in the aurt9792 mutation site region. The mutation in aurt9792 occurs at a highly conserved lysine. Red stars (A,C) indicate amino acid directly affected by the mutations. D.r., Danio rerio; X.t., Xenopus tropicalis; H.s., Homo sapiens; G.g., Gallus gallus; M.m., Mus Musculus. Bottom row numbers are the Consistency Score according to the PRALINE protein alignment program. (D-G′) The CRISPR/Cas9-generated mid1ip1luw39 allele does not complement aurt9792. (D,E) All embryos from aurt9792/mid1ip1luw39 transheterozygous females (E) exhibit reduced membrane integrity (asterisk), reduced yolk coalescence (arrowhead) and regressed furrows (arrow; see also Fig. S1A,B), whereas control embryos from heterozygous siblings (D) are wild type in appearance. (F,G) 8-cell embryos from transheterozygous females exhibit reduced β-Catenin accumulation in mature furrows (27/27; G,G′, arrowheads), ectopic CGs throughout the cortex (G) and apparently stabilized FMA (G′, arrow), compared with control siblings (0/25; F,F′). (F′,G′) Higher magnifications of boxed regions in F,G. Scale bars: 100 μm in F,G; 10 μm in F′,G′.

Attempts to prove gene identity through functional manipulation of in vitro maturing oocytes (Nair et al., 2013a) or early embryos failed to yield conclusive results (data not shown). We therefore induced mutations in mid1ip1l through CRISPR-mediated gene targeting and tested a newly induced allele for complementation against the existing maternal-effect aura (aurt9792) mutation. The mutant was made by targeting mid1ip1l in an N-terminal region of the Mid1ip1l protein (see Materials and Methods). The resulting CRISPR-generated allele, mid1ip1luw39, has a 2 bp insertion after 116 bp of the coding region, which results in normal protein sequence until amino acid 39, followed by out-of-frame sequence until amino acid 90 and translational termination (Fig. 9A, Fig. S6C). Females transheterozygous for this mid1ip1luw39 allele and the maternal-effect mutation aurt9792 were generated through natural crosses and, like aura homozygotes, were viable and capable of producing embryos. These embryos exhibited a 100% penetrant maternal-effect phenotype essentially identical to that of aura mutant embryos (Fig. 9D-G), indicating that these mutations are allelic. Similar maternal-effect phenotypes were observed in embryos from females homozygous for the mid1ip1luw39 allele (Fig. S1; data not shown). We do not observe any zygotic phenotype associated with the mid1ip1luw39 mutation. Altogether, our experiments demonstrate that aura is mid1ip1l.

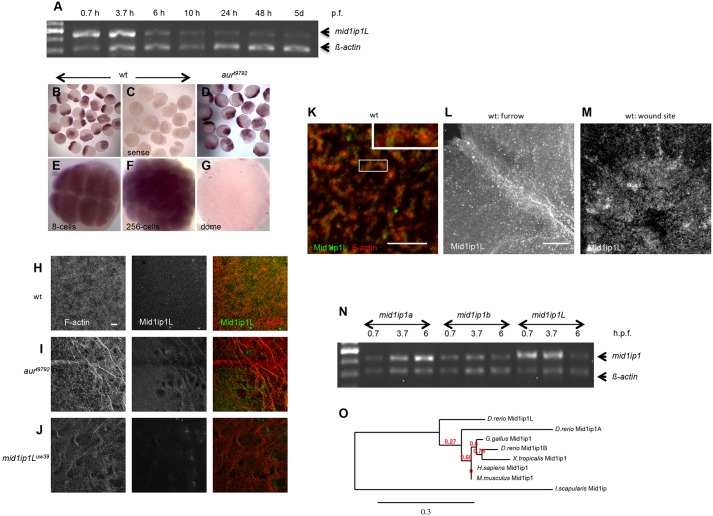

Expression of aura (mid1ip1l) indicates a predominant role in the early embryo

RT-PCR analysis suggests that mid1ip1l is present at high levels as maternal RNA early in development (up to 3.7 hpf), with progressively reduced expression at later developmental stages (Fig. 10A,N). Whole-mount in situ hybridization to detect mid1ip1l in wild-type embryos corroborated the RT-PCR results, with uniformly distributed mid1ip1l RNA present at high levels during early development (2-cell to 256-cell stage, Fig. 10B,E,F) and thereafter experiencing a severe reduction (Fig. 10G,N; data not shown). The levels and distribution of maternal mid1ip1l RNA during the early stages appear similar in aurt9792 mutant embryos (Fig. 10D). Previous studies have shown that zygotic mid1ip1l transcription is initiated in the pharyngula (24 h) stage embryo, with specific expression in hatching gland precursor (polster) cells (Thisse et al., 2001).

Fig. 10.

Expression of mid1ip1l and gene phylogeny. (A) RT-PCR analysis over developmental time (h or days post fertilization) of mid1ip1l RNA, co-amplifying β-actin RNA as an internal control. mid1ip1l RNA is maternally expressed, with levels subsiding at later stages. (B-G) In situ hybridization analysis. mid1ip1l antisense probes label early cleavage stage embryos (B, 25/25; E,F), with a reduction by dome stage (20/20; G). Levels and distribution of mid1ip1l RNA are similar in aura mutants (from aurt9792/t9792 females, D). Control sense RNA (C). (H-J) Mid1ip1l antibodies label within cortical F-actin in wild type (26/26; H). Reduced labeling is observed in aurt9792 embryos (20/20; I) and no localization in mid1ip1l uw39 embryos (21/21; J). (K) Higher resolution imaging of wild type (from H) shows Mid1ip1l protein localizing as puncta within cortical F-actin aggregates (8/8). Insert (K) shows a 2× magnification of the boxed region. In wild type, Mid1ip1l protein becomes enriched at the forming furrow (4/4; L) and induced wounds (4/4; M). (H-L) 45 mpf; (M) 15 mpf. (N) RT-PCR analysis of mid1ip1a, mid1ip1b and mid1ip1l. RT-PCR data (A,N) are representative of two trials. (O) Phylogenetic tree for Mid1ip1 protein shows zebrafish mid1ip1b as most closely related to other vertebrate mid1ip1 genes, and mid1ip1a and mid1ip1l as products of gene duplication. Ixodes scapularis (deer tick) is an outgroup. Numbers in red indicate branch support values; number in black indicates branch scale bar. Scale bars: 10 μm in H-J,L,M; 5 μm in K.

To detect Mid1ip1l expression and localization, we generated antibodies against regions of the protein (see Materials and Methods). Western analysis with antibodies against Mid1ip1l shows that they recognize a single band of the expected size in wild-type but not mutant embryos (Fig. S6D). Immunolabeling of fixed wild-type embryos shows that Mid1ip1l protein is distributed within the cortical F-actin network (Fig. 10H,K), at the developing furrows (Fig. 10L) and at induced wounds (Fig. 10M). As expected, labeling is reduced and undetectable, respectively, in mutants for the aurt9792 and mid1ip1luw39 alleles (Fig. 10I,J). High-magnification imaging of cortical F-actin reveals punctate Mid1ip1l within F-actin aggregates (Fig. 10K).

There are two other mid1ip1-related genes in zebrafish: mid1ip1a and mid1ip1b. RT-PCR analysis shows that these genes produce maternal transcripts at levels lower than mid1ip1l (Fig. 10N). Both mid1ip1a and mid1ip1b become zygotically active during embryonic development: mid1ip1a exhibits a burst of activity at the initiation of epiboly (4.5 hpf, Fig. 10N) (Kassahn et al., 2009) and mid1ip1b begins expression at the bud stage (10 hpf, Fig. 10N; data not shown). Bioinformatic searches of available databases indicate that vertebrates, including humans, mouse, Xenopus tropicalis and chicken, contain a single mid1ip1 gene, whereas teleost fish contain three mid1ip1-related copies: mid1ip1(a), mid1ip1b and mid1ip1l. Phylogenetic analysis is consistent with the Mid1ip1b form in fish lineages retaining closer relatedness to tetrapod Mid1ip1, with functional diversification of the Mid1ip1l and Mid1ip1a forms in fish lineages (Fig. 10O, Fig. S6E).

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that the zebrafish gene aura, previously identified as a maternal-effect lethal mutation, corresponds to the mid1 interacting protein 1 family gene mid1ip1l. Our analysis shows that aura mutant embryos exhibit a variety of defects at the egg-to-embryo transition, including CG release, cortical integrity, cytokinesis completion and wound repair, and suggests defective cytoskeletal reorganization as a likely underlying cause for these defects.

Identification of aura as encoding Mid1ip1l and use of Cas9/CRISPR to confirm gene identification

A positional cloning approach reveals that the maternal-effect mutation in aura is associated with a 24 amino acid C-terminal truncation in the gene mid1ip1l, which in its wild-type form encodes a 164 amino acid protein. The C-terminal region deleted in the maternal-effect aurt9792 mutation is highly conserved across mid1ip1 genes in other species, suggesting that this mutation interferes with protein function.

Corroboration of gene identity is a challenge for maternal-effect genes, as their products typically act immediately or shortly after egg activation (Lindeman and Pelegri, 2012; Nair et al., 2013a,b). Indeed, our attempts to manipulate Aura function during oogenesis led to variable results. In order to fully prove that aura and mid1ip1l are the same gene, we employed the CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate an additional allele in mid1ip1l. This CRISPR-generated mutation proved to be allelic to aura in a genetic complementation assay. Thus, CRISPR-mediated gene knockout allowed us to bypass underlying difficulties in gene identity confirmation.

Aura (Mid1ip1) is essential for cytoskeletal dynamics at the egg-to-embryo transition

The mid1ip1 gene, also known as MIG12, was originally identified as encoding a protein interactor of Mid1 (Berti et al., 2004). Mid1 is a TRIM/RBCC protein implicated in X-linked Opitz G/BBB syndrome in humans, a genetic syndrome characterized by a variety of midline abnormalities (Quaderi et al., 1997; Gaudenz et al., 1998; Cox et al., 2000; De Falco et al., 2003; Winter et al., 2003). Mid1ip1 family proteins are known to associate with the microtubule cytoskeleton and are thought to aid Mid1 in the regulation of microtubule dynamics (Berti et al., 2004), and have also been shown to play a role in the regulation of lipogenesis (Inoue et al., 2011).

Our studies show that maternally provided aura (mid1ip1l) product is essential for a variety of processes at the egg-to-embryo transition, including CG release and the completion of cytokinesis (Fig. 10), as well as membrane integrity and repair. One of the processes affected in aura mutants is the restructuring of the FMA during furrow maturation, in agreement with the previously proposed role for Mid1ip1 in microtubule dynamics (Berti et al., 2004). Other microtubule-based processes, such as spindle formation and function, appear unaffected.

Our analysis also suggests a role for Aura in F-actin regulation. Previous studies have shown that CG release depends on the disassembly of the F-actin cortex during egg activation (Becker and Hart, 1999), and the CG release defect in aura/mid1ip1l mutants suggests a role for Aura in this cytoskeletal restructuring. Similarly, aura/mid1ip1l mutants show a defect in the dynamic reorganization of F-actin at the cortex prior to furrow formation and in its accumulation at the cleavage plane during furrow formation, as well as during wound repair. Accordingly, immunolabeling with antibodies raised to Mid1ip1l protein indicate that it localizes to F-actin. Together with the effects of inhibitors of actin dynamics in these mutants, our results suggest that Mid1ip1l promotes F-actin reorganization by facilitating F-actin polymerization and/or stabilization. As in the case of the microtubule cytoskeleton, not all F-actin-based processes are strongly affected in aura/mid1ip1l mutants: blastodisc cell lifting, which is known to depend on F-actin (Leung et al., 2000), is only mildly affected, and the initial contraction of the furrow, which is presumably dependent on the contractile ring, appears unaffected in these mutants.

Our findings are consistent with a previously proposed role for Mid1ip1 in the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics and expand its targets to include the actin cytoskeleton. We cannot rule out the possibility that some of the observed effects are secondary consequences of undetected earlier developmental defects. However, imaging and inhibitor studies, including Mid1ip1l protein localization, argue for a direct role for this factor in F-actin dynamics in the early embryo. Further research will be required to better understand the precise role of Aura (Mid1ip1l) in cytoskeletal regulation, as well as its potential connection to Mid1 and Opitz G/BBB syndrome.

Sequestration of a membrane subcompartment in aura/mid1ip1l mutants

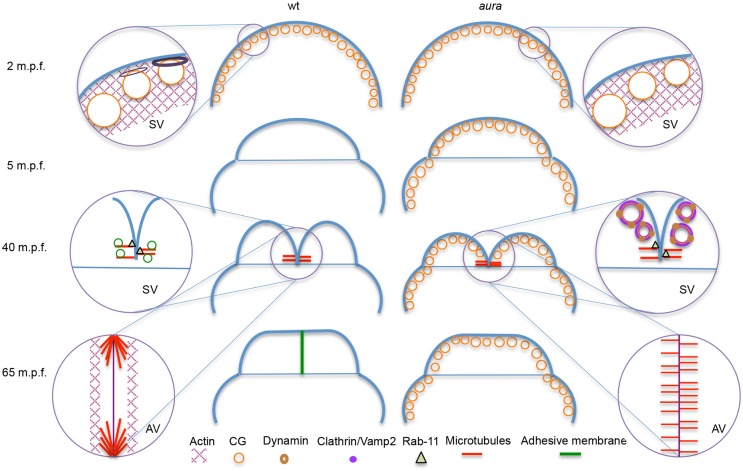

Embryonic cell division involves a marked increase in surface area, which depends on the exocytosis of internal membrane during cytokinesis. The early defect in aura/mid1ip1l mutants generates the unusual situation in which embryonic processes proceed in spite of the absence of early CG exocytosis. Instead, the membrane subcompartment corresponding to CGs is arrested in the early embryo (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Summary of the effects on cytoskeletal and membrane dynamics observed in aura/mid1ip1l early mutant embryos. Key processes in early wild-type embryos (left) and defects in aura/mid1ip1l mutants (right), focusing on cytoskeletal dynamics and exocytosis of internal membrane. In mutants, during egg activation CGs fail to be released, possibly owing to the inability to restructure cortical actin. During furrow formation, the microtubule-based FMA fails to reorganize and pericleavage F-actin-rich regions are reduced. Failure of pericleavage F-actin enrichment and sequestration of CG internal membrane in mutants results in the inability to form interblastomere adhesive membrane. Exocytic and endocytic components, such as Vamp2, Clathrin and Dynamin 2, become localized to unreleased CGs in mutants and are unavailable. The exocytic factor Rab11 exhibits normal furrow localization in the mutants. AV, animal view; SV, side view.

Previous studies have shown that, in normal embryos, CG release is tightly coupled to membrane endocytosis in order to regulate membrane surface area and reconstitute internal stores essential for membrane addition during embryonic cell division. Exocytic markers such as Vamp2 do not accumulate at the furrow in aura mutants, exhibiting instead localization to unreleased CGs. This is consistent with the idea that CGs constitute an early embryonic membrane compartment that is reused at a later stage for membrane addition during cell division. By contrast, the exocytic targeting factor Rab11 exhibits normal localization at the furrow, coincident with the tip of FMA tubules. This finding suggests that Rab11 localization to the furrow occurs through transport along microtubules, consistent with previous studies (Takahashi et al., 2012), and suggests that this transport is independent of membrane compartment association.

Surprisingly, unreleased CGs in aura mutants also accumulate membrane proteins involved in membrane endocytosis, such as Dynamin and Clathrin (Hinshaw, 2000; Royle, 2006). In addition to its role in endocytosis, Dynamin has been shown to have a role in the regulation of fusion pore widening after exocytosis (Anantharam et al., 2011). Thus, Dynamin rings observed on unreleased CGs might represent intermediates with stalled exocytosis. Alternatively, the localization of these endocytic proteins to unreleased CGs might reflect that anchors for these factors pre-exist in the CG membrane compartment, in anticipation of immediate endocytosis after CG release (Hart and Collins, 1991; Bement et al., 2000). Indeed, Dynamin has been shown to act in a reinternalization mechanism involving direct membrane retrieval after exocytosis (Holroyd et al., 2002; Ryan, 2003).

The CG release defect in aura/mid1ip1l mutants results in the sequestration of a membrane subcompartment within the embryo, making it unavailable for subsequent use during cell cleavage. This sequestration is likely to contribute to the defect in late cytokinesis, which requires membrane addition (Skop et al., 2001; Strickland and Burgess, 2004; Barr and Gruneberg, 2007). The association of the cell adhesion junction component β-Catenin to ectopic CGs in aura/mid1ip1l mutants further suggests that CGs might be preloaded with factors used at later stages of development, such as anchors for cell adhesion junction components that may become active during cytokinesis. Wound healing is also known to depend on membrane exocytosis (McNeil, 2002) and, although CGs do not appear to participate in this process (McNeil et al., 2000), aberrant membrane recycling might also contribute to the wound healing defect observed in aura mutants.

Diversification of mid1ip1 genes in the zebrafish

The zebrafish genome contains three mid1ip1-related genes. This is somewhat surprising considering the expected duplicate copies from a whole-genome duplication event that occurred early in the teleost lineage. mid1ip1b, which is most closely related in sequence to other vertebrate mid1ip1 genes, is widely expressed in the zebrafish embryo. By contrast, both mid1ip1a and mid1ip1l (aura) have specific patterns of expression: mid1ip1a as a temporal spike at the beginning of gastrulation and mid1ip1l largely as a maternal transcript but also zygotically expressed in hatching gland precursor cells. These expression patterns indicate functional mid1ip1 gene diversification within the teleost lineage.

Conclusions

In summary, we have determined that a maternal-effect mutation in aura corresponds to a mutation in mid1ip1l, the product of which was known to associate with the Opitz G/BBB syndrome factor Mid1 and thought to contribute to microtubule dynamics. We show that zebrafish aura (mid1ip1l) function is required for cytoskeletal reorganization at the egg-to-embryo transition, involving not only microtubules but also F-actin. In addition, CG sequestration in aura/mid1ip1l mutants suggests multiple pathways for exocytic factors and underscores the requirement for membrane recycling in the early embryo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic methods

Fish were maintained under standard conditions at 28.5°C (Brand et al., 2002). aurt9792 was generated in an AB/Tübingen hybrid background (Pelegri et al., 2004). Wild-type stocks were WIK for the mapping crosses and AB for functional analysis. Wild-type embryos were tested as a mixed pool and mutant embryos were tested as separate clutches, in both cases derived from two to four females. Transgenic lines were EMTB [Tg(EMTB-3GFP)] (Wühr et al., 2010) and LifeAct [Tg(actb2:LIFEACT-GFP)] (Behrndt et al., 2012). All animal experiments were conducted according to University of Wisconsin – Madison and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines (University of Wisconsin – Madison assurance number A3368-01).

Positional cloning was carried out as described (Pelegri and Mullins, 2011). First-pass mapping with 214 SSLP markers distributed 10 cM apart showed linkage of aura to LG 14. A second phase of mapping from genotyped parents narrowed the genomic region to a 1.2 cM interval and a polymorphism from the left end of BAC CR388071.10 to 0.23 Mb (Fig. S6).

Fluorescence imaging

Embryos were fixed with paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde after dechorionation (Urven et al., 2006) and oocyte labeling was carried out as previously described (Gupta et al., 2010). Primary antibodies: mouse anti-α-Tubulin (1:2500; Sigma, T5168), rabbit anti-β-Catenin (1:1000; Sigma, C2206), rabbit anti-Vamp2 (1:200; Abcam, ab70222), rabbit anti-Rab11b (1:200; GeneTex, GTX127328), rabbit anti-Dynamin 2 (1:100; GeneTex, GTX127330), rabbit anti-Clathrin (1:200; Abcam, ab59710) and rabbit anti-Vamp4 (1:400; SySy, 136 002). Mouse anti-Mid1ip1l (1:400; Antibodies-Online) was derived from three separate peptides in the middle of Mid1ip1l and thus able to detect aurt9792 but not mid1ip1luw39.

For CG analysis, embryos were fixed with paraformaldehyde, dechorionated, washed in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and labeled with Alexa-488-conjugated phalloidin (Thermo Fisher, A12379) for 1 h at room temperature and Alexa-555-conjugated WGA (Life Technologies; 1:100) for 30 min at 37°C. When colabeling with anti-Clathrin and anti-Dynamin 2, WGA was used first as it binds antibodies. Embryos were semi-flat mounted. For F-actin, the paraformaldehyde fix contained 0.2 U/ml Rhodamine-phalloidin for preservation and imaging. Immunofluorescence data are from at least duplicate trials. Quantification of the CG release phenotype was carried out by comparing the total number of CGs in 60× magnification cortical fields at 0 and 10 min post activation from the same females (aura, six fields per time point; wild type, four fields per time point). Epifluorescence images were captured using a Zeiss Axioplan 2. Confocal microscopy images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 (for fixed images and live movies at low magnification) or Zeiss LSM 780 (for live movies at high magnification) and processed with Fiji.

Drug treatment

Wild-type and aurt9792 embryos were dechorionated and exposed to drug treatment at 15 mpf. Concentrations of inhibitors in E3 medium: cytochalasin D, 20 μg/ml; phalloidin, 10 μg/ml; nocodazole, 2 μg/ml; and taxol, 10 μg/ml.

Histology and in situ hybridization

Dissected wild-type and aurt9792 ovaries were fixed overnight in paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS and dehydrated in ethanol. Ovaries were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, stained and mounted as described previously (Gupta et al., 2010). mid1ip1l was amplified using wild-type 2-cell embryo cDNA with forward and reverse primers (Table S1), the latter including a T7 promoter. Riboprobes were synthesized using digoxigenin-labeled UTP (Sigma, 3359247910) and in situ hybridization was carried out as described previously (Pelegri and Maischein, 1998). Images of labeled embryos and sectioned ovaries were acquired using a Leica FLIII microscope and Spot Insight camera (Diagnostic Instruments). Data are from at least duplicate trials.

Functional manipulation and molecular methods

RNA was generated from the cDNA product (see above) using the T7 RNA ULTRA mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion) and poly(A) tailed. RNA was mixed with 0.2 M KCl and injected into oocytes (Nair et al., 2013a,b). Embryo RNA was extracted with Trizol (Thermo Fisher, 15596026) and subject to RT-PCR using gene-specific mid1ip1l/a/b and β-actin 1 primers (Table S1).

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees, sequence alignment and phenotypic prediction were carried out using Phylogeny.fr (Dereeper et al., 2008, 2010), PRALINE (CIBVU) and SuSPect (Yates et al., 2014), respectively.

CRISPR/Cas9

sgRNA was designed using http://crispr.mit.edu, PCR amplified with universal primers (Bassett et al., 2013) and in vitro transcribed using the T7 Flash Kit (Epicentre). Plasmid #46757 pT3TS::nCas9n (Jao et al., 2013; Moreno-Mateos et al., 2015) was digested with XbaI, purified and transcribed using the T3 mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion). Cas9 RNA and sgRNA were injected at 100 ng/μl and 30 ng/μl, respectively. Injected fish were raised and mated to wild-type fish. The next generation was raised and sequenced (C.E. and F.P., unpublished). Sequencing in transheterozygotes was carried out through a nested PCR approach.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Martin Wühr and Tim Mitchison (Harvard University) and Carl-Philippe Heisenberg (IST, Austria) for transgenic lines; and Dr Gratz for CRISPR mutation consultation and Drs Moreno-Mateos and Giraldez for their unpublished CRISPR/Cas9 protocol.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

C.E. performed phenotypic, cytoskeletal, CG release, membrane factor, expression and wounding analyses, confirmed gene identification, and prepared the manuscript. B.S. performed linkage, cytoskeletal and CG release analyses. F.P. prepared the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [GM065303 to F.P.; GM108449 to C.E.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.130591/-/DC1

References

- Albertson R., Riggs B. and Sullivan W. (2005). Membrane traffic: a driving force in cytokinesis. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 92-101. 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson R., Cao J., Hsieh T.-S. and Sullivan W. (2008). Vesicles and actin are targeted to the cleavage furrow via furrow microtubules and the central spindle. J. Cell Biol. 181, 777-790. 10.1083/jcb.200803096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam A., Bittner M. A., Aikman R. L., Stuenkel E. L., Schmid S. L., Axelrod D. and Holz R. W. (2011). A new role for the dynamin Gtpase in the regulation of fusion pore expansion. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 1907-1918. 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr F. A. and Gruneberg U. (2007). Cytokinesis: placing and making the final cut. Cell 131, 847-860. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett A. R., Tibbit C., Ponting C. P. and Liu J.-L. (2013). Highly efficient targeted mutagenesis of Drosophila with the Crispr/Cas9 system. Cell Rep. 4, 220-228. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K. A. and Hart N. H. (1996). The cortical actin cytoskeleton of unactivated zebrafish eggs: spatial organization and distribution of filamentous actin, nonfilamentous actin, and myosin-II. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 43, 536-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K. A. and Hart N. H. (1999). Reorganization of filamentous actin and myosin-II in zebrafish eggs correlates temporally and spatially with cortical granule exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 112, 97-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrndt M., Salbreux G., Campinho P., Hauschild R., Oswald F., Roensch J., Grill S. W. and Heisenberg C.-P. (2012). Forces driving epithelial spreading in zebrafish gastrulation. Science 338, 257-260. 10.1126/science.1224143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bembenek J. N., Richie C. T., Squirrell J. M., Campbell J. M., Eliceiri K. W., Poteryaev D., Spang A., Golden A. and White J. G. (2007). Cortical granule exocytosis in C. Elegans is regulated by cell cycle components including separase. Development 134, 3837-3848. 10.1242/dev.011361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bement W. M., Mandato C. A. and Kirsch M. N. (1999). Wound-induced assembly and closure of an actomyosin purse string in Xenopus oocytes. Curr. Biol. 9, 579-587. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80261-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bement W. M., Benink H., Mandato C. A. and Swelstad B. B. (2000). Evidence for direct membrane retrieval following cortical granule exocytosis in xenopus oocytes and eggs. J. Exp. Zool. 286, 767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti C., Fontanella B., Ferrentino F. and Meroni G. (2004). Mig12, a novel opitz syndrome gene product partner, is expressed in the embryonic ventral midline and co-operates with mid1 to bundle and stabilize microtubules. BMC Cell Biol. 5, 9 10.1186/1471-2121-5-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M., Granato M. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (2002). Keeping and raising zebrafish. In Zebrafish - A Practical Approach, Vol. 261 (ed. Nüsslein-Volhard C. and Dahm R.), pp. 7-37. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conner S., Leaf D. and Wessel G. (1997). Members of the snare hypothesis are associated with cortical granule exocytosis in the sea urchin egg. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 48, 106-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox T. C., Allen L. R., Cox L. L., Hopwood B., Goodwin B., Haan E. and Suthers G. K. (2000). New mutations in mid1 provide support for loss of function as the cause of X-linked opitz syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2553-2562. 10.1093/hmg/9.17.2553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilchik M. V., Funk W. C., Brown E. E. and Larkin K. (1998). Requirement for microtubules in new membrane formation during cytokinesis of Xenopus embryos. Dev. Biol. 194, 47-60. 10.1006/dbio.1997.8815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilchik M. V., Bedrick S. D., Brown E. E. and Ray K. (2003). Furrow microtubules and localized exocytosis in cleaving Xenopus Laevis embryos. J. Cell Sci. 116, 273-283. 10.1242/jcs.00217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco F., Cainarca S., Andolfi G., Ferrentino R., Berti C., Rodríguez Criado G., Rittinger O., Dennis N., Odent S., Rastogi A. et al. (2003). X-linked opitz syndrome: novel mutations in the Mid1 gene and redefinition of the clinical spectrum. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 120A, 222-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., Audic S., Buffet S., Chenevet F., Dufayard J. F., Guindon S., Lefort V., Lescot M. et al. (2008). Phylogeny.Fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W465-W469. 10.1093/nar/gkn180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereeper A., Audic S., Claverie J.-M. and Blanc G. (2010). Blast-explorer helps you building datasets for phylogenetic analysis. BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 8 10.1186/1471-2148-10-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosch R., Wagner D. S., Mintzer K. A., Runke G., Wiemelt A. P. and Mullins M. C. (2004). Maternal control of vertebrate development before the midblastula transition: mutants from the zebrafish I. Dev. Cell 6, 771-780. 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mestrah M. and Kan F. W. (2001). Distribution of lectin-binding glycosidic residues in the hamster follicular oocytes and their modifications in the Zona pellucida after ovulation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 60, 517-534. 10.1002/mrd.1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faire K. and Bonder E. M. (1993). Sea urchin egg 100-kDa dynamin-related protein: identification of and localization to intracellular vesicles. Dev. Biol. 159, 581-594. 10.1006/dbio.1993.1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández J., Valladares M., Fuentes R. and Ubilla A. (2006). Reorganization of cytoplasm in the zebrafish oocyte and egg during early steps of ooplasmic segregation. Dev. Dyn. 235, 656-671. 10.1002/dvdy.20682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes R. and Fernández J. (2010). Ooplasmic segregation in the zebrafish zygote and early embryo: pattern of ooplasmic movements and transport pathways. Dev. Dyn. 239, 2172-2189. 10.1002/dvdy.22349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudenz K., Roessler E., Quaderi N. A., Franco B., Feldman G., Gasser D. L., Wittwer B., Montini E., Opitz J. M., Ballabio A. et al. (1998). Opitz G/Bbb syndrome in Xp22: mutations in the Mid1 gene cluster in the carboxy-terminal domain. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 703-710. 10.1086/302010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giansanti M. G., Belloni G. and Gatti M. (2007). Rab11 is required for membrane trafficking and actomyosin ring constriction in meiotic cytokinesis of Drosophila males. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 5034-5047. 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta T., Marlow F. L., Ferriola D., Mackiewicz K., Dapprich J., Monos D. and Mullins M. C. (2010). Microtubule actin crosslinking factor 1 regulates the balbiani body and animal-vegetal polarity of the zebrafish embryo. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001073 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart N. H. and Collins G. C. (1991). An electron-microscope and freeze-fracture study of the egg cortex of Brachydanio rerio. Cell Tissue Res. 265, 317-328. 10.1007/BF00398079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart N. H., Wolenski J. S. and Donovan M. J. (1987). Ultrastructural localization of lysosomal enzymes in the egg cortex of brachydanio. J. Exp. Zool. 244, 17-32. 10.1002/jez.1402440104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw J. E. (2000). Dynamin and its role in membrane fission. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 483-519. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisaoka K. K. and Firlit C. F. (1960). Further Studies on the embryonic development of the zebrafish, Brachydanio Rerio (Hamilton-Buchanan). J. Morphol. 107, 205-225. 10.1002/jmor.1051070206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd P., Lang T., Wenzel D., De Camilli P. and Jahn R. (2002). Imaging direct, dynamin-dependent recapture of fusing secretory granules on plasma membrane lawns from Pc12 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16806-16811. 10.1073/pnas.222677399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idone V., Tam C., Goss J. W., Toomre D., Pypaert M. and Andrews N. W. (2008). Repair of injured plasma membrane by rapid Ca2+-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 180, 905-914. 10.1083/jcb.200708010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J., Yamasaki K., Ikeuchi E., Satoh S.-i., Fujiwara Y., Nishimaki-Mogami T., Shimizu M. and Sato R. (2011). Identification of MIG12 as a mediator for stimulation of lipogenesis by LXR activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 25, 995-1005. 10.1210/me.2011-0070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao L.-E., Wente S. R. and Chen W. (2013). Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a Crispr nuclease system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13904-13909. 10.1073/pnas.1308335110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesuthasan S. (1998). Furrow-associated microtubule arrays are required for the cohesion of zebrafish blastomeres following cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 111, 3695-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagaraj P., Gautier-Stein A., Riedel D., Schomburg C., Cerdà J., Vollack N. and Dosch R. (2014). Souffle/spastizin controls secretory vesicle maturation during zebrafish oogenesis. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004449 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassahn K. S., Dang V. T., Wilkins S. J., Perkins A. C. and Ragan M. A. (2009). Evolution of gene function and regulatory control after whole-genome duplication: comparative analyses in vertebrates. Genome Res. 19, 1404-1418. 10.1101/gr.086827.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C. F., Webb S. E. and Miller A. L. (2000). On the mechanism of ooplasmic segregation in single-cell zebrafish embryos. Dev. Growth Differ. 42, 29-40. 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2000.00484.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. M., Webb S. E., Lee K. W. and Miller A. L. (2006). Recruitment and snare-mediated fusion of vesicles in furrow membrane remodeling during cytokinesis in zebrafish embryos. Exp. Cell Res. 312, 3260-3275. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. M., Webb S. E., Chan C. M. and Miller A. L. (2008). Multiple roles of the furrow deepening Ca2+ transient during cytokinesis in zebrafish embryos. Dev. Biol. 316, 228-248. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman R. E. and Pelegri F. (2012). Localized products of Futile Cycle/Lrmp promote centrosome-nucleus attachment in the zebrafish zygote. Curr. Biol. 22, 843-851. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandato C. A. and Bement W. M. (2001). Contraction and polymerization cooperate to assemble and close actomyosin rings around Xenopus oocyte wounds. J. Cell Biol. 154, 785-798. 10.1083/jcb.200103105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow F. L. and Mullins M. C. (2008). Bucky ball functions in Balbiani body assembly and animal–vegetal polarity in the oocyte and follicle cell layer in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 321, 40-50. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L. (2002). Repairing a torn cell surface: make way, lysosomes to the rescue. J. Cell Sci. 115, 873-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L., Vogel S. S., Miyake K. and Terasaki M. (2000). Patching plasma membrane disruptions with cytoplasmci membrane. J. Cell Sci. 113, 1891-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei W., Lee K. W., Marlow F. L., Miller A. L. and Mullins M. C. (2009). Hnrnp I is required to generate the Ca2+ signal that causes egg activation in zebrafish. Development 136, 3007-3017. 10.1242/dev.037879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Mateos M. A., Vejnar C. E., Beaudoin J.-D., Fernandez J. P., Mis E. K., Khokha M. K. and Giraldez A. J. (2015). Crisprscan: designing highly efficient sgRNAs for Crispr-Cas9 targeting in vivo. Nat. Methods 12, 982-988. 10.1038/nmeth.3543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S., Lindeman R. E. and Pelegri F. (2013a). in vitro oocyte culture-based manipulation of zebrafish maternal genes. Dev. Dyn. 242, 44-52. 10.1002/dvdy.23894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S., Marlow F., Abrams E., Kapp L., Mullins M. and Pelegri F. (2013b). The chromosomal passenger protein Birc5b organizes microfilaments and germ plasm in the zebrafish embryo. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003448 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse B. M. (1976). Clathrin: a unique protein associated with intracellular transfer of membrane by coated vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73, 1255-1259. 10.1073/pnas.73.4.1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri F. and Maischein H.-M. (1998). Function of zebrafish β-catenin and Tcf-3 in dorsoventral patterning. Mech. Dev. 77, 63-74. 10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri F. and Mullins M. (2011). Genetic screens for mutations affecting adult traits and parental-effect genes. Methods Cell Biol. 104, 83-120. 10.1016/B978-0-12-374814-0.00005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri F., Knaut H., Maischein H.-M., Schulte-Merker S. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1999). A mutation in the zebrafish maternal-effect gene Nebel affects furrow formation and Vasa RNA localization. Curr. Biol. 9, 1431-1440. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80112-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegri F., Dekens M. P. S., Schulte-Merker S., Maischein H.-M., Weiler C. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (2004). Identification of recessive maternal-effect mutations in the zebrafish using a gynogenesis-based method. Dev. Dyn. 231, 324-335. 10.1002/dvdy.20145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier A., Chauvin J.-P. and Lecuit T. (2003). Trafficking Through Rab11 endosomes is required for cellularization during Drosophila embryogenesis. Curr. Biol. 13, 1848-1857. 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaderi N. A., Schweiger S., Gaudenz K., Franco B., Rugarli E. I., Berger W., Feldman G., Volta M., Andolfi G., Gingenkrantz S. et al. (1997). Opitz G/Bbb syndrome, a defect of midline development, is due to mutations in a new ring finger gene on Xp22. Nat. Genet. 17, 285-291. 10.1038/ng1197-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport R. (1996). Cytokinesis in Animal Cells. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Royle S. J. (2006). The cellular functions of clathrin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1823-1832. 10.1007/s00018-005-5587-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T. A. (2003). Kiss-and-run, fuse-pinch-and-linger, fuse-and-collapse: the life and times of a neurosecretory granule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2171-2173. 10.1073/pnas.0530260100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skop A. R., Bergmann D., Mohler W. A. and White J. G. (2001). Completion of cytokinesis in C. Elegans requires a brefeldin A-sensitive membrane accumulation at the cleavage furrow apex. Curr. Biol. 11, 735-746. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00231-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland L. I. and Burgess D. R. (2004). Pathways for membrane trafficking during cytokinesis. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 115-118. 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S., Kubo K., Waguri S., Yabashi A., Shin H.-W., Katoh Y. and Nakayama K. (2012). Rab11 regulates exocytosis of recycling vesicles at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 125, 4049-4057. 10.1242/jcs.102913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theusch E. V., Brown K. J. and Pelegri F. (2006). Separate pathways of RNA recruitment lead to the compartmentalization of the zebrafish germ plasm. Dev. Biol. 292, 129-141. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B., Pflumio S., Fürthauer M., Loppin B., Heyer V., Degrave A., Woehl R., Lux A., Steffan T., Charbonnier X. Q. et al. (2001). Expression of the zebrafish genome during embryogenesis. Zfin Direct Data Submission, https://zfin.org/ZDB-PUB-010810-1.

- Togo T. and Steinhardt R. A. (2004). Nonmuscle myosin IIA and IIB have distinct functions in the exocytosis-dependent process of cell membrane repair. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 688-695. 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P.-S., van Haeften T. and Gadella B. M. (2011). Preparation of the cortical reaction: maturation-dependent migration of snare proteins, clathrin, and complexin to the porcine oocyte's surface blocks membrane traffic until fertilization. Biol. Reprod. 84, 327-335. 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urven L. E., Yabe T. and Pelegri F. (2006). A role for non-muscle myosin II function in furrow maturation in the early zebrafish embryo. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4342-4352. 10.1242/jcs.03197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S. E., Goulet C., Chan C. M., Yuen M. Y. F. and Miller A. L. (2014). Biphasic assembly of the contractile apparatus during the first two cell division cycles in zebrafish embryos. Zygote 22, 218-228. 10.1017/S0967199413000051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel G. M. and Wong J. L. (2009). Cell surface changes in the egg at fertilization. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 76, 942-953. 10.1002/mrd.21090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J., Lehmann T., Suckow V., Kijas Z., Kulozik A., Karlsheuer V., Hamel B., Devriendt K., Opitz J. M., Lenzner S. et al. (2003). Duplication of the Mid1 first exon in a patient with opitz G/Bbb syndrome. Hum. Genet. 112, 249-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wühr M., Tan E. S., Parker S. K., Detrich H. W. and Mitchison T. J. (2010). A model for cleavage plane determination in early amphibian and fish embryos. Curr. Biol. 20, 2040-2045. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe T., Ge X., Lindeman R., Nair S., Runke G., Mullins M. and Pelegri F. (2009). The maternal-effect gene Cellular Island encodes aurora B kinase and is essential for furrow formation in the early zebrafish embryo. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000518 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates C. M., Filippis I., Kelley L. A. and Sternberg M. J. E. (2014). Suspect: enhanced prediction of single amino acid variant (Sav) phenotype using network features. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 2692-2701. 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]