Abstract

The increased demand for evidence-based practice in health policy in recent years has provoked a parallel increase in diverse evidence-based outputs designed to translate knowledge from researchers to policy makers and practitioners. Such knowledge translation ideally creates user-friendly outputs, tailored to meet information needs in a particular context for a particular audience. Yet matching users’ knowledge needs to the most suitable output can be challenging. We have developed an evidence synthesis framework to help knowledge users, brokers, commissioners and producers decide which type of output offers the best ‘fit’ between ‘need’ and ‘response’. We conducted a four-strand literature search for characteristics and methods of evidence synthesis outputs using databases of peer reviewed literature, specific journals, grey literature and references in relevant documents. Eight experts in synthesis designed to get research into policy and practice were also consulted to hone issues for consideration and ascertain key studies. In all, 24 documents were included in the literature review. From these we identified essential characteristics to consider when planning an output—Readability, Relevance, Rigour and Resources—which we then used to develop a process for matching users’ knowledge needs with an appropriate evidence synthesis output. We also identified 10 distinct evidence synthesis outputs, classifying them in the evidence synthesis framework under four domains: key features, utility, technical characteristics and resources, and in relation to six primary audience groups—professionals, practitioners, researchers, academics, advocates and policy makers. Users’ knowledge needs vary and meeting them successfully requires collaborative planning. The Framework should facilitate a more systematic assessment of the balance of essential characteristics required to select the best output for the purpose.

Keywords: Communication research into policy, evidence into policy, knowledge

Key Messages

The increased demand for evidence-based health policy in recent years has provoked a parallel increase in diverse evidence-based outputs designed to translate knowledge from researchers to policy makers and practitioners, yet matching users’ specific knowledge needs to the most suitable output, while essential, can be challenging.

We have developed an evidence synthesis framework classifying 10 distinct evidence synthesis outputs under four domains: key features, utility, technical characteristics and resources, in relation to six primary groups of users—professionals, practitioners, researchers, academics, advocates and policy makers.

We propose a process for matching users’ knowledge needs with an appropriate evidence synthesis output, using essential characteristics to consider when planning an output—Readability, Relevance, Rigour and Resources.

When used in combination, the framework and process should facilitate a more systematic assessment of the balance of essential characteristics required to select the best output for the purpose and help knowledge users, brokers, commissioners and producers decide the best ‘fit’ between ‘need’ and ‘response’.

Introduction

Increasing demands for the use of knowledge to assist evidence-based practice have led to a bourgeoning of different responses from funders and academics to evidence synthesis designed to support knowledge translation (Hansen and Rieper 2009). Each synthesis method and the type of output produced has its own merits and fulfils a particular knowledge need, for a particular primary audience, in a particular context. There are a number of factors that need to be considered when planning an evidence synthesis output including timeliness, length and format and the type of information to be included—whether solely research-based information, or the views of experts in the field, or a hybrid of both (Ogilvie et al. 2009; Abrami et al. 2010).

A diverse range of evidence synthesis outputs has been developed to meet users’ knowledge needs, including evidence articles, evidence briefs, knowledge summaries and systematic reviews. Yet identifying the most suitable evidence synthesis method and type of output for a particular need may be far from straightforward. One reason for this is that the labels given to different forms of output are not standardized, leaving scope for misunderstanding when commissioning and designing such reports (Arksey and O’Malley 2005; Grant and Booth 2009).

Each potential audience has different knowledge needs and the evidence may need to be presented in different ways to enhance its utility. Based on the opinions of an expert panel, we focus on six primary audiences: researchers, academics (who may also be researchers), advocates (largely those working for non-governmental organizations, NGOs), policy makers, administrative and managerial professionals, and practitioners. (The latter two groups are concerned with policy implementation, through delivering services and may also include NGO workers). Each of these groups requires knowledge for different purposes (Table 1). Evidence syntheses may have mutliple users and be used at mutliple levels of the health system. The audience groups that we have not addressed are considered in the discussion section, as one of the study’s limitations.

Table 1.

Users’ knowledge needs

| Academics and researchers | Advocates | Policy makers | Professionals and practitioners |

|---|---|---|---|

| To critically appraise new and exisiting research and identify gaps in research, to both verify and generate knowledge | To have an overview of research with illustrative evidence-based case studies to inform advocacy for changes in policy and practice | To gain an understanding of validated concepts, experiences and technical knowledge on which to develop new or change existing policy | To have access to validated concepts, experiences and technical knowledge to assist with implementing policy and best practice |

This study aims to contribute to an understanding of different users’ knowledge needs and how they can be met through matching them with relevant evidence synthesis outputs. The objectives are to identify: different evidence synthesis outputs and their distinguishing features; as well as issues to consider when planning the development of an evidence synthesis to match users’ knowledge needs.

We have created an evidence synthesis framework describing the features, benefits and limitations of outputs, based on a literature search, and consultations and interviews with experts in the field of synthesizing research for policy and practice. This framework should benefit both commissioners and producers of synthesis outputs—including knowledge brokers, who are responsible for deciding which type of output will best meet the needs of the evidence users they support.

The scope of this study is the wide range of diverse evidence synthesis outputs, which encompasses, but is not exclusive to systematic reviews. Much of the existing literature focuses on methodologies to analyse quantitative and/or qualitative studies that are variants of systematic reviews, e.g. Gough and Elbourne 2002; Mays et al. 2005; Tricco et al. 2011; Hansen and Rieper 2009. These are well-defined, distinct approaches (e.g. meta-analysis, or realist, diagnostic test or complex reviews etc.). However in this study, the nature of systematic reviews is acknowledged as a generic type of evidence synthesis output.

Methods

A four-strand literature search, described below, was conducted to ascertain what research exists that contributes to answering the study objectives. Using the methodology for a systematic review was not feasible because of the nature of the documents on which the literature search was based. Such documents, for policy makers and a general audience are not generally found in databases of academic peer-reviewed articles. Nevertheless, the methodology we used followed parameters which were intended to make it systematic.

The first strand of the literature search was a search of five bibliographic databases of peer-reviewed journal articles: Embase, Global Health, Medline, Social Policy & Practice and Web of Science. Based on the number of relevant articles from particular journals identified in the database search, the second strand was a hand search of three peer-reviewed journals that were considered particularly relevant: Systematic Reviews Journal; Journal of Health Services Research & Policy; and BMC Medical Research Methodology. The third strand was a search for relevant grey literature using Google. This was not exhaustive, but was as comprehensive as possible, representing five leading organizations involved in producing evidence syntheses: the UK Department for International Development (DFID), the Overseas Development Institute, INASP (an international development charity working with a global network of partners to improve access, production and use of research information and knowledge), the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3iE). DFID’s Research for Development (R4D) database was also searched.

The inclusion criteria for the literature search were that articles were written in English and were either review or discussion articles. The initial search terms used for the first two strands of the literature review were:

evidence synthesis (singular and plural) AND methodology.

A second search of the bibliographic databases was then undertaken using the search terms (expert opinion OR consensus statement) AND policy making.

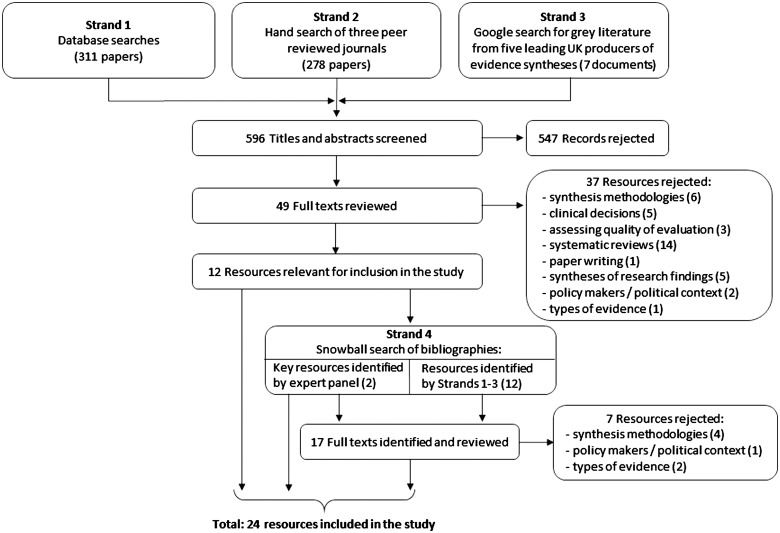

Once the search results were compiled using Endnote, the titles and abstracts (or executive summaries) of all records were appraised and 49 were considered to be relevant. Given the small number of documents, one researcher read all 49 in full and made a decision as to whether or not they met the study objectives of identifying different types of evidence synthesis, or highlighted issues to consider when planning the development of an evidence synthesis to match users’ knowledge needs (Supplementary data 1 are available at HEAPOL online). Twelve documents were considered to meet these objectives. The fourth strand of the literature search was to use a snowball technique to identify further documents from the references cited in these 12 documents, as well as two key documents identified by the expert panel we consulted, bringing the total number of relevant documents to 24. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the literature search. One researcher conducted the literature search and the decisions made were reviewed with a second researcher at regular intervals.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search

Experts in synthesis designed to get research into policy and practice were also consulted to hone issues for consideration and ascertain key studies. We consulted with a panel of eight experts, from diverse backgrounds, with experience of producing evidence syntheses. They were selected purposively because they represented the various types of expertize needed to produce such outputs and included a leading research scientist involved in knowledge translation, health system researchers, advocacy and communications specialists and representatives from large organisations that regularly produce evidence synthesis outputs, and advisers to policy makers (Supplementary data 2 are available at HEAPOL online). Prior to the literature search, a discussion guide was devised to focus phone and face-to-face meetings with four of these experts. It included identifying the need for evidence syntheses, the value of a question-based evidence synthesis, the value of synthesized evidence versus expert opinion, sound examples of typologies of evidence syntheses and different types of evidence synthesis outputs and their relative validity.

These meetings developed into free-flowing discussion, providing insights and suggestions that helped to determine some of the essential characteristics of different types of evidence synthesis outputs. These discussions informed a manual synthesis of the literature search findings, from which a framework and report were developed with the participation of all eight experts, who gave useful feedback, particularly in fine-tuning the framework and recommendations.

Results

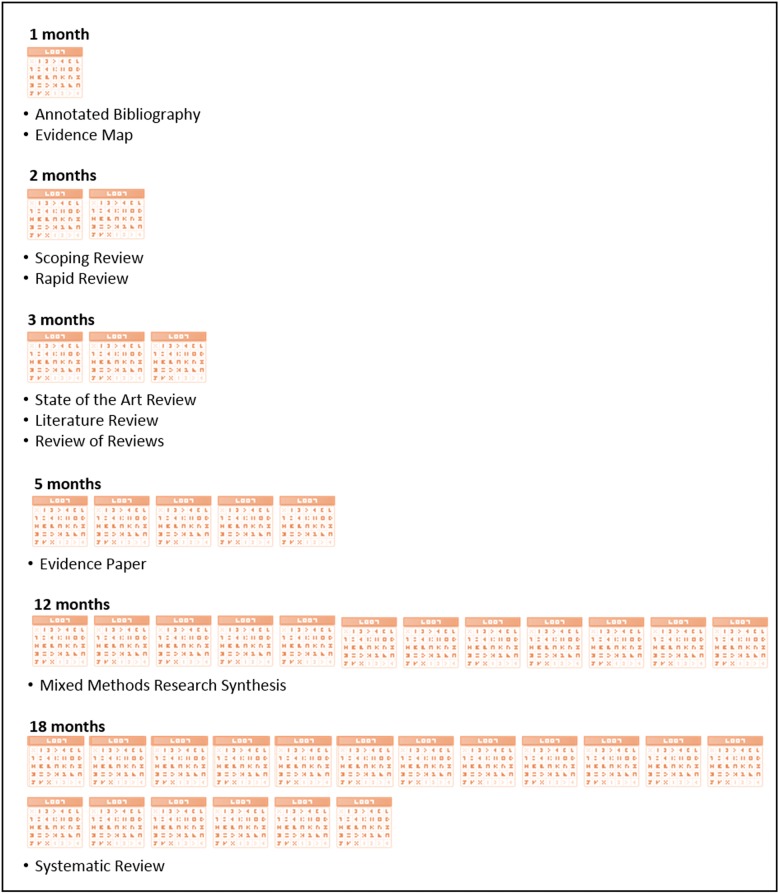

We identified 10 different forms of evidence synthesis outputs and have classified them in an evidence synthesis framework. The Framework arranges the characteristics of these outputs under four domains: there is a brief description of each output’s key features; its utility for the primary audience we suggest it is best suited to; technical characteristics, including limitations; (Tables 2–4) and the production resources that should be considered, in order to meet knowledge users’ needs, such as a timeframe (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Evidence synthesis framework—key features of forms of evidence synthesis outputs

| Evidence synthesis outputs based on a broad thematic overview |

Evidence synthesis outputs based on a specific question |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commonly used name | Annotated bibliography | Evidence map | Scoping review | State of the art review | Rapid review | Literature review | Review of reviews | Evidence paper | Mixed methods research synthesis | Systematic review |

| Also known as | Mapping review | Critical review | Knowledge summary | Evidence summary | Overview | Umbrella review | Evidence briefing | Multi-arm systematic review | ||

| Systematic map | Scoping study | Rapid evidence assessment | Overview of reviews | Briefing note | Mixed studies review | |||||

| Interim evidence assessment | Evidence to policy brief | |||||||||

| Brief review | Evidence brief | |||||||||

| Strategy brief | Research summary | |||||||||

| Description | A list of key literature and/or sources, primarily of research evidence with expanded summaries on the main content | A map of the existing research evidence base to provide an overview of key themes and/ or results and identify research gaps | An overview of research undertaken on a (constrained) topic, when time and other constraints are limited | A brief review primarily of recent research evidence | A quick review of key, easily accessible evidence, from research and other sources, on a particular (constrained) topic | An overview and synthesis primarily of research evidence with key conclusions | Includes existing reviews, preferably systematic rather than primary studies, and draws a conclusion statement | An extensive overview of available and accessible evidence—both peer reviewed and significant grey literature—primarily from research | A full map and synthesis of different types of research evidence—both quantitative and qualitative—to answer a research question and subquestions | An exhaustive and robust review and synthesis of research evidence |

| Often produced for a specific, time bound purpose | Often produced for a specific, time bound purpose | Often produced for a specific, time bound purpose | May include a consensus statement drawing on practice-based evidence | Often produced for a specific, time bound purpose | Is likely to include a critical appraisal of research | Includes a balanced, objective assessment and critical appraisal of the evidence | May include statistical meta-analysis of quantitative medical research and a synthesis of qualitative data | Includes a map of evidence, critical appraisal and qualitative or quantitative evidence synthesis | ||

| May give an indication of areas of consensus and debate | Includes a commentary on evidence | Mixed methods research syntheses include realist reviews and meta-narrative reviews | Includes the criteria (e.g. quality, date range, method) applied to select evidence for synthesis | |||||||

| Includes peer-reviewed literature and is likely to include grey literature | May consider local context and cost effectiveness | Incorporates peer-reviewed and significant grey literature | ||||||||

| Draws a clear scientific conclusion | ||||||||||

Table 3.

Evidence synthesis framework—utility of different forms of evidence synthesis outputs for their primary audience

| Evidence synthesis outputs based on a broad thematic overview |

Evidence synthesis outputs based on a specific question |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commonly used name | Annotated bibliography | Evidence map | Scoping review | State of the art review | Rapid review | Literature review | Review of reviews | Evidence paper | Mixed methods research synthesis | Systematic review |

| Suggested primary audience | Researchers/academics | Researchers/academics | Researchers/academics | Advocates/ Policy makers | Policy makers | Researchers/academics | Researchers/academics | Professionals/practitioners | Professionals/practitioners | Professionals |

| When is it useful? | To identify documents that may have particular relevance to a topic | To give an overview of key issues and where or what evidence exists | To determine the range of studies that are available on a specific topic | To provide timely evidence to support advocacy for policy and practice | To provide a rapid overview of key issues and publications for a specific, immediate purpose (e.g. workshop input, speech, timely policy decisions, initial scoping) | To provide information on a specific topic in a short period of time | When there is a considerable body of research and a number of research reviews in a particular area | To set out a comprehensive evidence base sufficient to underpin policy decisions or programme designs | When a synthesis of both statistical and qualitative data are required, drawn from a wide range of sources | When time and resources are available, this provides the most comprehensive and authoritative summary of a body of evidence at a particular point in time, to underpin policy decisions or programme designs |

| May complement other review outputs, particularly rapid reviews or evidence maps | May inform more in-depth reviews | To determine the value of undertaking a systematic review | To help identify key issues and/or questions for more in-depth reviews | To synthesize the existing evidence base as a guide for policy and programme decisions within a set timeframe | When time and/or fiscal resources are not available for a full systematic review | Provides a comprehensive and authoritative summary of a body of evidence at a particular point in time, to underpin policy decisions or programme designs | ||||

| To summarize and disseminate research findings | To determine existing evidence and identify future evidence needs | May form the basis for a full systematic review | ||||||||

| To identify research gaps in the existing literature | May direct or refine questions for more in-depth reviews | |||||||||

| Examples | http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/40740.html | http://www.hindawi.com/journals/drt/2012/820735/ | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3128401/ | http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/summaries/ks27/en/index.html | http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/events/2013/au_policy_brief_aids_tb_malaria.pdf?ua = 1 | http://www.health.vic.gov.au/agedcare/maintaining/downloads/healthy_litreview.pdf | http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/part_publications/essential_interventions_18_01_2012.pdf | http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/economics/costoolsreviewpack.pdf?ua = 1 | http://www.physiotherapyuk.org.uk/visiting/programme/presentations/2199 | http://www.globalizationandhealth.com/content/9/1/15 |

| http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/2011_accountability-mechanisms/en/ | ||||||||||

Table 4.

Evidence synthesis framework—technical characteristics of different forms of evidence synthesis outputs

| Evidence synthesis outputs based on a broad thematic overview |

Evidence synthesis outputs based on a specific question |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commonly used name | Annotated bibliography | Evidence map | Scoping review | State of the art review | Rapid review | Literature review | Review of reviews | Evidence paper | Mixed methods research synthesis | Systematic review |

| Quality appraisal of evidence | Limited | Limited | Limited | Limited | Limited | Limited | Essential | Essential | Essential | Essential |

| Evidence usually presented as | Reference list | Graphics and tables | Narrative and tables | Narrative, graphics and tables | Narrative and tables | Narrative | Narrative, graphics and tables | Narrative and tables | Narrative, graphics and tables | Narrative and tables |

| Systematic documentation of evidence | Limited | Comprehensive | Limited | Limited | Comprehensive | Comprehensive | Comprehensive | Comprehensive | Comprehensive | Comprehensive |

| Replicable | Low | Medium | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | Medium | High |

| Periodic update | Possible | Possible | Possible | Possible | Possible | Possible | Essential | Possible | Possible | Essential |

| Limitations | Does not synthesize or analyse findings across sources | Overview, not in-depth analysis | May have: A narrow focus question | -Evidence base not comprehensive, limited to most recent scientific information | Evidence base not comprehensive | Prone to selection and publication bias - tends to review readily available evidence | Does not include research outside existing reviews | Limited accessibility to literature | Time consuming and resource intensive | Resource intensive (time, human, financial) |

| Generally does not appraise evidence | Does not synthesize or analyse findings across sources | Few search sources | May be prone to bias | Relies on easily accessible/ available evidence | Often limited detail on search strategies, or how conclusions reached | Because reviews are of variable quality, each needs to be assessed for how systematic and comprehensive it is | Time/human resource constraints likely to limit scope | May have a narrow clinical question or set of questions | ||

| Prone to selection and publication bias | A range of evidence may be covered, but generally relies on few search sources | Use only key terms for search (not all variants) | Prone to selection and publication bias | Resources determine scope, which may limit comprehensive-ness or lead to inconclusive findings | Limited literature search | Has a history of use in health and education; yet to be fully tested in other development areas, e.g. governance and climate change | ||||

| Prone to selection and publication bias | Be limited to electronic and easily available documents | Risk of generating inconclusive findings that provide a weak answer to the original question | ||||||||

| ; | A simple description with limited analysis | |||||||||

Figure 2.

Resources: Indicative production times for evidence synthesis outputs

Different forms of evidence synthesis outputs and their distinguishing features

These outputs synthesize different types of evidence; some include evidence outside that produced by scientific research. Hansen and Rieper (2009) observe the rise of evidence-based policy making and delivery in Europe since the 1990s and differentiate between the forms of evidence used, based on Eraut’s (2004) work on the credibility of evidence used for decision making. Eraut distinguishes between research-based evidence in peer-reviewed published research; other scientific evidence (generated using scientific procedures with a track record of producing valid results); and practice-based evidence (derived from recognized professional practices that have been undertaken using criteria expected by experts within the profession). Any, or all of these could make a valid and useful contribution, but may not in themselves be sufficient to meet policy makers’ needs.(Mays et al. 2005) The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH) strategy briefs (2014b) are an example of practice-based evidence syntheses combined with tools to develop and implement strategies to inform advocacy, policy and practices.

We found a number of studies that describe some of the different evidence synthesis outputs in similar terms, and these have contributed to the development of the evidence synthesis framework, yet none covers all four domains. For example, to help commissioners identify which evidence synthesis output would best suit a particular need, the UK Civil Service (2010) and DFID (2013) suggest when an output might be useful and its limitations, but neither includes many technical characteristics. Other frameworks are based on synthesis methods, but do not take users’ perspectives or the resources required into account. Grant and Booth (2009) present a comparison framework based on the four main processes used to review evidence—Search, AppraisaL, Synthesis and Analysis (SALSA)—to distinguish between different syntheses and define their characteristics. Classification differences mean that some of the outputs they identify share a definition in the Framework we have developed. Kastner et al. (2012) also map the characteristics of existing evidence synthesis methods, and Tricco et al. (2011) use the qualitative or quantitative nature of sources of evidence to tabulate the characteristics of different synthesis methods, which they refer to as ‘…types of systematic reviews’.

Other studies focus on evidence synthesis outputs guided by a clear question and primarily synthesizing research evidence, and present methodological frameworks based on the type of research question to which an answer is sought (Petticrew and Roberts 2003; Mays et al. 2005). The need for an evidence synthesis to have a research or learning question came up repeatedly in the literature search and was discussed with the expert panel. A carefully structured research or learning question can help to clarify and target the literature search and places the synthesis within a context, including a theoretical context (Gough and Elbourne 2002) and some consider that it guides the whole production process (Gough and Elbourne 2002; Petticrew and Roberts 2003; Mays et al. 2005; DFID Evidence Brokers 2013).

For researchers and practitioners, who are generally concerned with impact and effectiveness issues, well-established outputs that are primarily based on research studies—such as systematic reviews—are designed to answer specific impact questions, e.g. What evidence is there that misoprostol can prevent postpartum haemorrhage? Although the knowledge to action (KTA) evidence summaries prepared as part of a collaborative project between the Champlain Local Health Integration Network and the University of Ottawa, funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, were not initially developed with a predetermined primary research question, user feedback suggested it would provide ‘clarity and direction’ (Khangura et al. 2012). An iterative process was built into future summaries, so that the research team worked with users to agree a research question. Similarly, Chambers and Wilson (2012) propose a checklist by which researchers and users’ representatives, or commissioners can clarify the research question.

UK Civil Service guidelines (2010) group evidence that can be synthesized around non-impact questions e.g. needs, process, implementation, correlation, attitude and economic questions, such as; How much does it cost to deliver misoprostol to pregnant women in community settings? Yet a research question may not be a key requirement for all knowledge users; for some, a more general focus might be appropriate. Advocates, policy makers and implementers may have a variety of issues to consider and require a range of evidence beyond scientific research, to guide them (Sheldon 2005; Lavis et al. 2009; Abrami et al. 2010). Davies (2006) notes that policy makers often want answers to broad questions, which may not always be sufficiently focussed to guide a tight search for evidence beyond that available from research; ‘such as administrative data and evidence used by lobbyists, pressure groups and think tanks (which may or may not be research based)’. While there are a limited number of databases available to help guide such searches, e.g. Open Grey, these are not exhaustive and often have a basic search function. A clear statement of the issue might be a more suitable starting point (Gough and Elbourne 2002; Petticrew et al. 2004; Mays et al. 2005; UK Civil Service 2010; Chambers and Wilson 2012; Khangura et al. 2012) as in the PMNCH knowledge summaries (2014a). Our evidence synthesis framework distinguishes between those evidence synthesis outputs which address a specific research question and those which provide a broad thematic overview of the evidence relating to issues in a policy area, such as significance, as in the PMNCH knowledge summary Maternal mental health: Why it matters and what countries with limited resources can do (Hashmi 2014).

Variations in the names and characteristics of some types of evidence synthesis outputs meant that categorizing them in the Framework was not always straightforward. For example, the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (2011) splits synthesis outputs into short syntheses and systematic reviews, noting that the names of short synthesis documents—policy brief, research summary and briefing note, ‘…are typically used indiscriminately, and could refer to similar or highly dissimilar ideas’. It reclassifies short synthesis outputs, by the type and extent of the information they summarize.

While standardizing the names and methods would help clarify and distinguish between outputs with partially or fully overlapping characteristics, some researchers consider this unnecessary or even restrictive, suggesting that a preferable solution would be to include a transparent statement of methods in each output (Gough and Elbourne 2002; Watt et al. 2008; Ganann et al. 2010). The Effective Health Care bulletins, commissioned by the English Department of Health, are one example where methodological information is included (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2004). Another is the evolution of evidence summaries produced under the KTA research programme, where iterative feedback from users of early summaries led to the development of a template that includes a methods section (Khangura et al. 2012).

Factors to consider when planning an evidence synthesis output

Planning an evidence synthesis ideally involves collaboration between those commissioning and those producing an output. The challenge is to ensure that it meets the users’ specific information needs, is user-friendly, timely and credible (Sheldon 2005). Consideration of some essential characteristics should help. When offering guidance to researchers writing for a diverse audience, Largay (2001) identifies Three Rs—Readability, Relevance and Rigour as essential characteristics. Rigour relates to the systematic and transparent application and recording of the method used. Relevance refers to planning the scope of the evidence synthesis to fit the knowledge requirements of potential users, ensuring timely production and identifying the primary audience—why the research topic is important to them and what the context is. Readability includes using plain, non-technical language, clarity of thought and a brief summary or visual display of the conclusions reached.

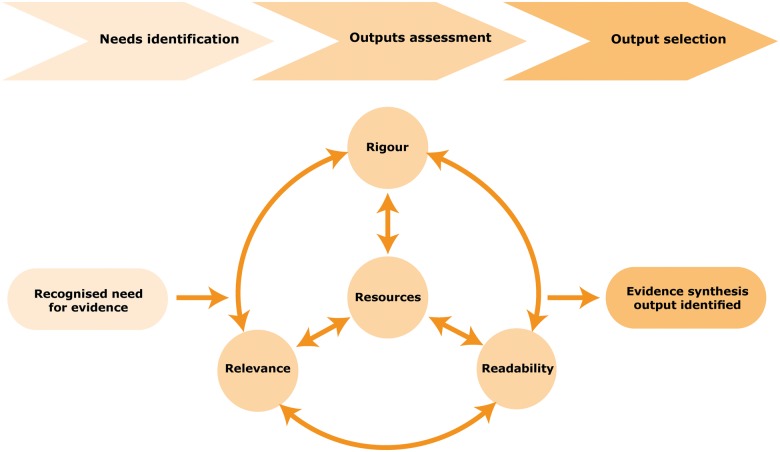

Considering the three Rs should help secure a credible, timely and appropriate output that meets users’ needs. Grant and Booth (2009) and Thomson (2013) highlight a tension between rigour and relevance, given that the opportunities for using an output, for example within a defined policy window, may not allow sufficient time to undertake a systematic review. To help address this, Thomson (2013) considers the Three Rs as ‘interrelated principles’ that can be applied to planning evidence syntheses, particularly complex reviews to support policy making, and suggests they are considered in relation to a fourth R—Resources available for production (including time, funding and personnel). This helps determine a feasible and relevant scope for the synthesis output within the time available. Building on Thomson’s concept, Figure 3 shows how the Four Rs fit into a process for matching information needs with appropriate evidence synthesis outputs: once the need for synthesized evidence has been established, an acceptable balance between the Four Rs is agreed and used to make an objective assessment of the types of evidence synthesis outputs, to help identify the most appropriate output.

Figure 3.

Process for matching information needs with an evidence synthesis output

Relevance often relates to the particular context in which evidence synthesis outputs are to be used (Petticrew et al. 2004; Sheldon 2005; Ogilvie et al. 2009; Chambers and Wilson 2012; Saul et al. 2013). Researchers and producers of evidence syntheses need to develop some understanding of the knowledge needs of the primary audience and the environment in which they are working so as to analyse and present the information in a way that is relevant and helpful to users (Sheldon 2005). Such factors may relate to context, cost effectiveness and expert—or even public—opinion (Ogilvie et al. 2009), e.g. PMNCH strategy briefs (2014b) are often produced in more than one language and use regional case studies, to support international or regional meetings.

A study eliciting the views of UK policy makers on how research evidence influences public health policy found that the attributes of evidence synthesis they considered to be important were broadly in line with three of the four Rs: clarity, timeliness and relevance to current policy debates, with the addition of attending to evidence of cost-effectiveness (Petticrew et al. 2004). In some instances, the inclusion of different types of evidence drawing on a wide range of information sources may be best suited to the production of a hybrid output that offers a peer-reviewed synthesis of recent scientific evidence with practical information for policy makers and practitioners (Abrami et al. 2010), such as the PMNCH knowledge summaries (2014a).

The relationship between the relevance of a synthesis output and the resources available to ensure its timeliness is an important planning consideration (Saul et al. 2013; Thomson 2013). Figure 2 gives indicative average production times for each of the evidence synthesis outputs in the evidence synthesis framework. Consideration of this and other resource issues by both commissioners and producers will likely affect various aspects of an output, including its rigour, depth, quality appraisal and scope. For example, resources generally influence the number of reviewers who can be employed to work on an output in the time available. Abrami et al. (2010) make this distinction clear by using brief review to describe a synthesis limited in both timeframe and scope, and comprehensive review, for one which is time bound, but not limited in scope because a number of researchers can work on it.

Discussion

The Framework identifies 10 different forms of evidence synthesis outputs drawn from the literature search and consultation with experts. It shows the range of outputs that have been developed in recent years to accommodate different evidence needs, beyond clinical decision making. Given the confusion produced by the many different terms used in the literature to describe these various forms of evidence synthesis outputs, the Framework, used in conjunction with the process for matching users’ information needs with an appropriate evidence synthesis output, is intended to offer greater clarity to users, commissioners and producers of outputs.

Using the process outlined in Figure 3, in conjunction with the evidence synthesis framework, offers a more systematic approach than was previously available to planning an appropriate evidence synthesis output by ensuring that all the essential features and characteristics, including resources, are considered. If planning is an iterative and participatory collaboration between users and/or commissioners and the production team, it will be a significant contributing factor towards producing an output tailored to meet users’ knowledge needs (Watt et al. 2008; Khangura et al. 2012; Saul et al. 2013) and increase the prospect of research being used in policy development (Corluka et al. 2014). Once the need for an evidence synthesis has been identified, those commissioning it should consider what sorts of evidence would be relevant and the level of rigour with which the evidence needs to be analysed for the particular context in which the synthesis will be used. In addition, the level of knowledge and understanding of the end-users needs to be appraised, to guide the level of technical language and detail that is required. Alongside these considerations, the resources available for production should also be taken into account. Taking the decisions made on relevance, rigour, readability and resources a match can then be made using the outputs listed in the Framework and the indicative average production times, in order to identify the most suitable output.

The strength of our approach was that we consulted with specialists in this field to guide the focus of the evidence synthesis framework and the process for matching users’ information needs with appropriate evidence synthesis outputs, but we acknowledge that in this field other perspectives on the issues considered may exist. Our approach had inevitable limitations. We were only able to search peer-reviewed studies and grey literature in English, and documents that were not widely available on the Internet, such as NGO reports, were not included. The specific needs of audience groups such as industry, the private sector, the media and the general public (who other than when involved in advocacy, have no defined role) were beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, this study addresses the needs of a wide range of users. An assessment of the in-depth knowledge needs of other audiences may require some adaptation of the framework.

Furthermore, while it was beyond the scope of this study, the use of the framework in conjunction with the process for identifying knowledge users’ information needs with an evidence synthesis output, would benefit from being pre-tested and pilot tested with different groups of knowledge users. Although the process currently suggests equal weighting is given to considerations of rigour, relevance, readability and resources, we would expect that different groups of policy and decision makers might emphasize different components in different contexts. For example, the primary concern for academic stakeholders might be rigour, while policy makers might consider readability and relevance to be of primary importance, and practitioners might prioritize relevance. The emphasis given to each component might lead to the adaptation and development of the framework, in order to increase its utility to different user groups.

Conclusion

Users’ knowledge needs vary and meeting them successfully requires collaborative planning. The Framework describes the various evidence synthesis outputs identified and the process for matching users’ information needs with an appropriate output. It is intended to offer a more systematic way for users, commissioners and producers to establish a common understanding of users’ knowledge needs, and the essential characteristics to be considered when matching those needs with the most suitable output, given the resources available.

Further work would help to address the limitations of this study, such as taking the knowledge needs of other audiences into account.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Wendy Graham (University of Aberdeen and DFID) and Mark Petticrew (LSHTM), for their input into the planning of this research; and Sanghita Battacharyya (Public Health Foundation of India), Alison Dunn (Consultant Writer, Editor and Communicator), Vaibhav Gupta (PMNCH) and Andy Haines (LSHTM) reviewing the research. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not the official position of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, PMNCH or the Department of Health. Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at HEAPOL online.

Funding

This analysis was funded by the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health (PMNCH) as part of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) work on the PMNCH Knowledge Summary series (2013/346244). N.M. and M.P. were also supported by the English Department of Health's Policy Research Programme funding for the Policy Innovation Research Unit (ref. 102/0001).

Conflict of interest statement. PMNCH, as an agency, had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis and writing of the article. S.K. as PMNCH staff at the time this analysis was undertaken, contributed as a technical expert in this area.

References

- Abrami PC, Borokhovski E, Bernard RM, et al. 2010. Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 6: 371–89. [Google Scholar]

- Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. 2011. HPSR Syntheses: Policy briefs, Research summaries, Briefings notes and Systematic Reviews. WHO. http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/synthesis/en/, accessed 14 May 2014 2014.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Theory and Practice, 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. [2004]. Effective Health Care bulletins.http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/ehcb_em.htm, accessed 10 September 2013.

- Chambers D, Wilson P. 2012. A framework for production of systematic review based briefings to support evidence-informed decision-making. Systematic Reviews 1: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corluka A, Cohen M, Lanktree E, et al. 2014. Uptaek and impact of research for evidence-based practice: lessons from the Africa Health Systems Initiative Support to African Research Partnerships. BMC Health Services Research 14(Suppl 1): I1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. 2006. What is needed from research synthesis from a policy-making perspective?. In: POPAY J. (ed). Moving Beyond Effectiveness in Evidence Synthesis: Methodological Issues in the Synthesis of Diverse Sources of Evidence. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- DFID Evidence Brokers. 2013. The evidence synthesis sourcebook. London: UK Department for International Development (DFID). [Google Scholar]

- Eraut M. 2004. Practice Based Evidence. In: THOMAS G, PRING R. (eds.) Evidence-based Practice in Education. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. 2010. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implementation Science, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough D, Elbourne D. 2002. Systematic research synthesis to inform policy, practice and democratic debate. Social policy and society, 1: 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Booth A. 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HF, Rieper O. 2009. The Evidence Movement: The Development and Consequences of Methodologies in Review Practices. Evaluation, 15: 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi IE. 2014. Maternal mental health: Why it matters and what countries with limited resources can do. PMNCH Knowledge Summary 31, Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner M, Triccoo AC, Soobiah C, et al. 2012. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Medical Research Methodology 12: 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, et al. 2012. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic Reviews 1: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largay J. 2001. Editorial: Three Rs and four Ws. Accounting Horizons 15: 71–2. [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J, Permanand G, Oxman A, et al. 2009. SUPPORT tools for evidence-informed health policymaking (STP) 13: Preparing and using policy briefs to support evidence-informed policy making. Health Research Policy and Systems 7: S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. 2005. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10: 6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie D, Craig P, Griffin S, et al. 2009. A translational framework for public health research. BMC public health, 9: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M, Roberts H. 2003. Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: horses for courses. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 57: 527–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Macintyre S, et al. 2004. Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 1: The reality according to policymakers. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 58: 811–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PMNCH. 2014a. PMNCH Knowledge Summaries.http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/summaries/en/, accessed 11 April 2014.

- PMNCH. 2014b. PMNCH strategy briefs.http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/strategybriefs/en/, accessed 25 July 2014.

- Saul JE, Willis CD, Bitz J, et al. 2013. A time-responsive tool for informing policy making: rapid realist review. Implementation Science, 8: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon T. 2005. Making evidence synthesis more useful for management and policy-making. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson H. 2013. Improving utility of evidence synthesis for healthy public policy: the three Rs (relevance, rigor, and readability [and resources]). American Journal of Public Health 103: e17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Tettzlaff J, Moher D. 2011. The art and science of knowledge synthesis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UK Civil Service. 2010. Rapid Evidence Assessment Toolkit Index. Rapid Evidence Assessment Toolkit [Online]. http://www.civilservice.gov.uk/networks/gsr/resources-and-guidance/rapid-evidence-assessment/what-is, accessed 23 October 2013.

- Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L, et al. 2008. Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: An inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 24: 133–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.