Abstract

In 2001, technocrats from four multilateral organizations selected the Millennium Development Goals mainly from the previous decade of United Nations (UN) summits and conferences. Few accounts are available of that significant yet cloistered synthesis process: none contemporaneous. In contrast, this study examines health’s evolving location in the first-phase of the next iteration of global development goal negotiation for the post-2015 era, through the synchronous perspectives of representatives of key multilateral and related organizations. As part of the Go4Health Project, in-depth interviews were conducted in mid-2013 with 57 professionals working on health and the post-2015 agenda within multilaterals and related agencies. Using discourse analysis, this article reports the results and analysis of a Universal Health Coverage (UHC) theme: contextualizing UHC’s positioning within the post-2015 agenda-setting process immediately after the Global Thematic Consultation on Health and High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda (High-Level Panel) released their post-2015 health and development goal aspirations in April and May 2013, respectively. After the findings from the interview data analysis are presented, the Results will be discussed drawing on Shiffman and Smith (Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. The Lancet 2007; 370: 1370–79) agenda-setting analytical framework (examining ideas, issues, actors and political context), modified by Benzian et al. (2011). Although more participants support the High-Level Panel’s May 2013 report’s proposal—‘Ensure Healthy Lives’—as the next umbrella health goal, they nevertheless still emphasize the need for UHC to achieve this and thus be incorporated as part of its trajectory. Despite UHC’s conceptual ambiguity and cursory mention in the High-Level Panel report, its proponents suggest its re-emergence will occur in forthcoming State led post-2015 negotiations. However, the final post-2015 SDG framework for UN General Assembly endorsement in September 2015 confirms UHC’s continued distillation in negotiations, as UHC ultimately became one of a litany of targets within the proposed global health goal.

Keywords: Post-2015, Millennium Development Goals, Sustainable Development Goals, Universal Health Coverage, global health, global health policy, agenda setting

Key Messages

In mid-2013, 40 in-depth interviews were conducted with participants from multilaterals and related agencies on global health’s location in the evolving post-2015 development agenda.

The majority of participants support the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda’s May 2013 report proposing ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ as the umbrella health goal.

With <2 years until the Millennium Development Goal deadline, the Member States will progress post-2015 global negotiations following the United Nation’s early lead.

Nonetheless, Universal Health Coverage remains very much on the post-2015 negotiation table, however, whether it becomes the overarching goal or an express sub-goal remains unclear.

Introduction

This study examines Universal Health Coverage’s (UHC) evolving location and distillation in post-2015 health and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) discourse in key informant interviews from June to July 2013. This was a critical temporal juncture in post-2015 global health debate, immediately after the Global Thematic Consultation on Health released its April 2013 report following 6-months of intensive stakeholder consultation (Global Thematic Consultation on Health 2013). The High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda (High-Level Panel), tasked by the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General to develop a visionary report to both stimulate and ground ensuing development goal discussion, offered its synthesis report in May 2013 (High-Level Panel 2013). The High-Level Panel’s report was both instructive and timely: in July 2013, the carriage of the post-2015 dialogue organically passed from the control of the UN Secretariat and its agencies to the Member State driven Open Working Group.

Our examination into UHC’s position within the unfolding post-2015 health and development goal discourse in June–July 2013 is part of the broader Goals and Governance for Health research project (Go4Health Project). Go4Health is a consortium of academics and civil society from the Global North and South established to advise the European Commission on the international health-related goals to follow the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Based on the insight offered by professionals working on health and the post-MDG agenda within multilaterals and related agencies, we have sought to examine why UHC, as a summative health goal, appears to have polarized opinion among these key actors, shaping and dividing UN perspectives on the health SDG and targets. The presentation of this evidence contrasts with the absence of contemporaneous, empirical documentation of the agenda-setting and decision-making process resulting in the MDGs. Although this research seeks to allow the complex responses of our respondents to speak for itself, our own advocacy position for a post-2015 health and development goal has been previously articulated: UHC, grounded in the right to health (Ooms et al. 2013, 2014).

Background

Learning lessons from the past

The analysis of how global health policy priorities form is a critical yet neglected area of scholarship (Shiffman et al. 2002; Shiffman and Smith 2007; Walt and Gilson 2014; Berlan et al. 2014). This truism is exemplified by ‘the obscurity’ (Darrow 2012) surrounding the formulation of the eight MDGs, originally published as an attachment to the UN Secretary General’s Road Map report in September 2001 (UN 2001). Within 5 years, the MDGs became ‘the blue print’ for global development policy and planning in the new Millennium (UN System Task Team 2012). The MDGs led to a reshaping of the health and development field, ‘Not just in terms of funding, policies and programming, but also in terms of the organization and dissemination of knowledge’ (Yamin and Boulanger 2013).

Yet from the literature available it is unclear exactly how or why the three express health-related MDGs (child survival: MDG 4; maternal health: MDG 5; HIV, malaria and other diseases: MDG 6) were chosen by the small UN inter-agency team tasked by Secretary-General Kofi Annan in the spring/summer of 2001 to devise the MDG list (Manning 2009; Hulme 2007, 2009a,b; Doyle 2011; Fehling et al. 2013). Some commentators posit they evolved from the goals and targets of the major UN Summits and Conferences in the 1990s (Vandemoortele 2005, 2011a,b; Waage et al. 2010); others consider the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee’s 1996 International Development Goals played a formative role (UNDP 2003; Eyben 2006; Saith 2006; Clemens et al. 2007; Manning 2009). Several sources claim it was a composite of both factors (White and Black 2004; Hulme and Scott 2010; Barnes and Wallace Brown 2011). It is also unclear why this specific cluster of global health issues were prioritized within the MDG framework, and unclear why MDG decision-makers essentially chose a targeted approach toward these specific health challenges. This approach, emphasizing the elimination of communicable disease, contrasts with the integration of a health systems strengthening approach advocated by the World Health Organization (WHO), and known to those framing the MDGs (Chan 2008; Lawn et al. 2008; Kitamura et al. 2013; Waage et al. 2010).

Opacity of the MDG agenda-setting and decision-making process is partly a consequence of the limited number of primary sources reporting on that high-level policy-making process at that time. However with the MDGs expiring in December 2015 and the UN General Assembly voting on a proposed list of 17 SDGs in September 2015 following worldwide discussion (Horton and Mullan 2015; UN General Assembly 2015), an important opportunity exists to both investigate and document emerging global health priorities in the dynamic SDG agenda-setting landscape. Although the MDG’s architects could not anticipate the enormous ramifications the eight MDGs, their targets and indicators would have on shaping global health planning and practice (Darrow 2012; Jones 2013; Vandemoortele 2013), the more transparent formulation of the SDGs provides an opportunity for contemporaneous and independent analysis of the process, informing contemporary health lobbyists and policymakers in their deliberations.

Agenda-setting

A policy agenda is a ‘[l]ist of issues to which an organization is giving serious attention at any one time with a view to taking some sort of action’ (Buse et al. 2005). The policy agenda is set pursuant to the agenda-setting process; ‘[the p]rocess by which certain issues come onto the policy agenda from the much larger number of issues potentially worthy of attention by policy makers’ (Buse et al. 2005). Applying Berlan et al.’s (2014) ‘restrictive definition’, agenda setting is ‘at its core… the attention paid to competing issues in society… not the specific decisions, budgetary allocations or policies enacted to address these issues’.

Identifying and analysing agenda-setting processes by which policies are initiated, developed or formulated is no easy task, especially so at the complex global policy-making level. At this, the highest of policy-making forums, the definition of the ‘organization’ (i.e. the decision-making entity) becomes blurred. Realists define the decision-maker as the UN Member States, while neoliberalists may narrow this to consist of the United States and/or its Global North allies (Chiaruzzi 2012). Alternatively, those aligned with a cosmopolitan or pluralistic theoretical construct of the global decision-making arena might posit the said policymakers consist of an intricate web of State and non-State actors (Beardsworth 2011; Rengger 2014).

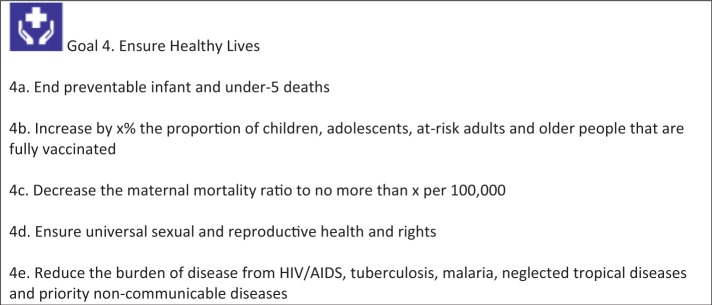

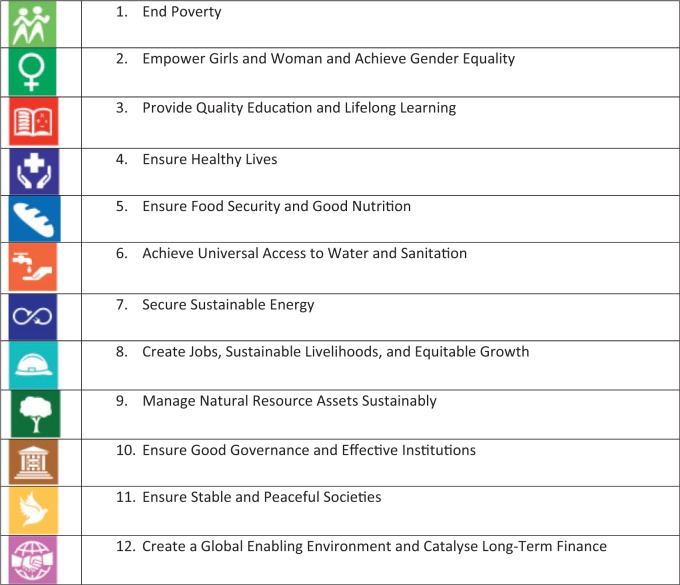

Certainly, the 27 members of the Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel are a diverse mix of actors stemming from an equally diverse array of issue-based State and non-State sectors and environments. The High-Level Panel comprised heads of government, key departmental ministers, career diplomats, international civil servants, academics, leaders of non-government organizations (NGOs), humanitarians and advocates, as well as private-sector and business executives. By way of their May 2013 report, this twenty-seven member High-Level Panel consciously set the post-2015 global health goal agenda by recommending an ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ umbrella goal (and five sub-goals or targets) (Figure 1), as the 4th of 12 ‘illustrative’ SDGs (Figure 2) (High-Level Panel 2013). The High-Level Panel were unequivocal as to their intentions: all twelve goals (and their targets) annexed to the May 2013 report were offered ‘as a basis for further discussion’:

Here we set out an example of what such a set of goals might look like. Over the next year and a half, we expect goals to be debated, discussed, and improved. But every journey must start somewhere.

Figure 1.

High-Level Panel’s suggested post-2015 health goal: Ensure Healthy Lives (High-Level Panel 2013).

Figure 2.

High-Level Panel’s 12 ‘illustrative’ post-2015 SDGs (High-Level Panel 2013).

In suggesting ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ be the post-2015 umbrella health goal, the High-Level Panel modified the Global Health Consultation’s ‘Maximizing Healthy Lives’ option, and relocated alternate health goals (in terms of title and content) from the epicentre of emerging post-2015 debate. UHC did not receive illustrative health goal status, and was omitted from the ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ goal’s five interconnected targets (see Figure 1). This marginalization seemed conceptually disabling: UHC was not authoritatively positioned within the agenda set by the High-Level Panel for ensuing Member State (and other inter-related) global health goal discussion.

UHC’s second-level prioritization within the Global Thematic Consultation report a month prior was surely influential, but not decisive. Certainly, agenda-setting processes are not always predicated on rational deliberation within a heuristic, linear, and somewhat temporal continuum that frames a static health policy agenda (Shiffman et al. 2002; Walt and Gilson 2014). The aim of this article, therefore, is to examine why UHC floundered in mid-2013 through the qualitative perspective of informants who sit at the post-2015 health policy interface between national governments and the UN. After we present the findings from our analysis of the interview data, our discussion will contextualize the results drawing on Shiffman and Smith’s (2007) agenda-setting analytical framework (examining ideas, issues, actors and political context), as modified by Benzian et al. (2011) (Table 1). This framework, endorsed by Walt and Gilson (2014), is utilized by several authors engaged in other global and national health policy agenda-setting studies (Schmidt et al. 2010; Keeling 2012; Pelletier et al. 2012; Tomlinson and Lund 2012).

Table 1.

Framework for analysis of factors shaping political priority (modified from Shiffman and Smith 2007) (Benzian et al. 2011)

| Analysis category | Factors shaping political priority |

|---|---|

| ‘Ideas’: the ways in which those involved with the issue understand and portray it | 1. ‘Internal frame’: the degree to which the policy community agrees on the definition of causes and solutions to the problem |

| 2. ‘External frame’: public portrayals of the issue in ways that resonate with external audiences, especially the political leaders that control resources | |

| ‘Issue characteristics’: features of the problem | 3. ‘Credible indicators’: clear measures that show the severity of the problem and that can be used to monitor progress |

| 4. ‘Severity’: the size of the burden relative to other problems, as indicated by objective measurement such as mortality and morbidity levels | |

| 5. ‘Effective interventions’: the extent to which proposed means of addressing the problem are clearly explained, cost-effective, backed by scientific evidence, simple to implement and inexpensive | |

| ‘Actor power’: strength of the individuals and organizations concerned with the issue | 6. ‘Guiding institutions’: the effectiveness of organizations or coordinating mechanisms with a mandate to lead the initiative |

| 7. ‘Policy community cohesion’: the degree of coalescence among the network of individuals and institutions centrally involved with the issue at the global level | |

| 8. ‘Leadership’: the presence of individuals capable of uniting the policy community and acknowledged as particularly strong leaders for the cause | |

| 9. ‘Civil society mobilization’: the extent to which grassroots organizations have mobilized to press international and national political authorities to address the issue at the global level | |

| ‘Political contexts’: the environments in which actors operate | 10. ‘Policy windows’: political moments when global conditions align favourably for an issue, presenting opportunities for advocates to influence decision makers |

| 11. ‘Global governance structure’: the degree to which norms and institutions operating in a sector provide a platform for effective action |

Methods

Study design

This qualitative research is part of Work Package 4 of the Go4Health Project. By engaging in dialogue with multilateral (UN Agencies, OECD and development banks) and related academic and civil society actors in a two-phased sequential research design, Work Package 4 aims to both trace and investigate the emergent post-2015 global governance of health landscape. It uses discourse analysis to locate the high-level policy debate around health goals in the broader discourse of the formulation of the post-2015 development goals in mid-2013 (Kelly and McGrath 1988; Sandelowski 1999; Hyatt 2005). Documentary analysis and in-depth interviews enabled an examination of discourse in its social, political, cultural and historical context (Lupton 1992; Milliken 1999; Cheek 2004; Starks and Brown Trinidad 2007). The discourse analysis was also designed to shed light on UHC’s trajectory in the post-2015 health goal agenda-setting landscape (Richardson 1992), as its location is of import to the Go4Health Project keen to see UHC elevated to post-2015 health and development goal status.

This study is grounded within the first research phase in mid-2013: it describes the knowledge and attitudes on the emergent formulation of the post-2015 health and development goal(s) framework in a cross-sectoral cluster of post-2015 policy spokespersons within key multilaterals and related global health agencies, based predominantly in New York, Washington DC, Paris and Geneva. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken over a 5-week period in June and July 2013, with the exception of three interviews. As has been mentioned, the timing of the interviews is significant to the context of the development of the post-2015 health goal agenda, and here we are mindful of Walt and Gilson’s (2014) guidance in the context of synthesizing agenda-setting studies:

Data extraction need to be undertaken chronologically where possible, so that a picture is built up over time. This is particularly important where policies are contested and rise up and fall off the policy agenda. Capturing time dimensions could also assist in more deliberate consideration of chains of causality…

In this regard, data collection for the second research phase began almost 12 months later in April–May 2014. Our findings regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and the human right to health in the evolving post-2015 policy agenda are published elsewhere (Brolan and Hill 2014). As discourse analysis can be understood as ‘an approach rather than a fixed method’ (Cheek 2004, p. 1145), this study therefore seeks to maintain tension between our analysis as a synchronic interpretation of the data, with the participant’s perspectives, which are grounded in a diachronic interpretation of a chronological or temporal sequence of post-2015 events to that point in time (i.e. the 5-week period within June–July 2013 in which interviews were conducted). We further acknowledge this synchronic-diachronic distinction is more complex than a static-dynamic distinction; e.g. ‘threaded through’ our own synchronic analytical positioning ‘are elements of a diachronic account’ of post-2015 events, an account that has evolved as our analysis has progressed (Davis 2008).

Participants

Most of the 40 interviews (33 face-to-face and 7 by Skype) were conducted by the two researchers (CEB and PSH) in June–July 2013. These included 57 participants (31 males and 26 females), with two additional participants providing email responses. Interviews covered 31 agencies: 17 multilaterals, 4 academic institutes, 3 foundations, 3 NGOs, two government agencies and 2 development banks (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of participant’s organizations (Brolan and Hill 2014)

| Agency |

|---|

| World Health Organization |

| Pan-American Health Organization |

| UNAIDS |

| The Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria |

| GAVI Alliance |

| UNICEF |

| UNs Development Programme |

| UNs Population Fund |

| UN Women |

| Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights |

| International Organization for Migration |

| UNs High Commissioner for Refugees |

| World Trade Organization |

| International Labour Organization |

| International Development Law Organization |

| Partnership for Maternal Newborn and Child Health |

| UN Foundation |

| Rockefeller Foundation |

| Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation |

| International Planned Parenthood Federation |

| International Committee of the Red Cross |

| Center for Global Development |

| College de France |

| Washington University |

| The New School |

| Georgetown University |

| US Government |

| Swedish Government |

| World Bank |

| Inter-American Development Bank |

Participants were purposively recruited from within multilateral organizations and associated agencies; the criterion for selection was that participants were responsible within their organizations for health in the post-2015 development goal agenda, or the post-2015 agenda more broadly. We began by listing the multilaterals, defining them primarily as UN organizations involved in the post-2015 global health agenda plus key development banks and global public–private partnerships with UN health organizations. Additional informants linked to the health multilaterals and the post-2015 agenda from government, academia, civil society and philanthropy were further identified.

Following initial contact by email and/or telephone we explained the purpose of our study and asked to undertake a face-to-face interview at each individual participant’s office. Interviewees were also asked to identify any additional individuals within their own or other organizations, directly related to the post-2015 agenda and to provide contact details and where appropriate, introductions. This combination of sampling strategies allowed flexibility, once in the field, to take advantage of developing events and relationships to locate key informants (Mays and Pope 1995; Onwuegbuzie and Leech 2007).

Data collection

Five questions were asked, adapted for the participant’s role and organizational context:

How was the participant’s organization engaging in post-2015 goal discussion?

What did the participant think about the High-Level Panel report, particularly the ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ goal?

What were the participant’s thoughts on the confluence of the SDG and post-MDG poverty reduction agenda?

What were the likely challenges in reaching global consensus on the post-2015 goals?

Which key actors outside the UN are likely to emerge in negotiating the post-2015 goals?

With participant’s consent, interviews were digitally-recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription service. Respondents were assigned an interview number (not in chronological order, and without qualification) to differentiate interviews but avoid identifying individual participants.

Analysis

Guided by Attride-Stirling’s (2001) approach to thematic analysis, CEB entered the transcripts into NVIVO 9 and engaged in a systematic immersion in the data. To heighten analytical rigour and inter-rata reliability (Armstrong et al. 1997), PSH initials independently reviewed CEB's coding tree, and both researchers discussed their analysis of the material. Synthesis of the data on a UHC theme resulted in the identification of five sub-themes. These five sub-themes form the findings for this paper, and contextualize UHC’s positioning within the post-2015 agenda-setting process immediately after the Global Thematic Consultation on Health and High-Level Panel released their post-2015 health and development goal aspirations in April and May 2013, respectively.

Approval for this research was from The University of Queensland School of Public Health Ethical Review Committee.

Results

Consensus for only one post-2015 health goal

Interviewees confirmed their expectation of a unitary health goal, in contrast to the three health MDGs. The Global Thematic Consultation on Health had cemented ‘the reality… health is not going to get more than one goal’ [Iv1557], though it would include a number of targets. No participant questioned this one health goal reality. Several debated whether the one goal likelihood is a product of the consultations (‘the idea of an inclusive goal was the strongest idea that came through the consultation’ [Iv1575]), or whether it was an input into the consultation process by facilitators to constrain debate: ‘If we look at the synthesis report [the Global Thematic Consultation on Health’s report, April 2013], this shows… better… the shepherding of the co-leads, in terms of the two major themes, healthy life expectancy and UHC’ [Iv1574]. Regardless, a number of participants agreed the High-Level Panel report of May 2013, containing only one illustrative health goal, foreshadowed a single, post-2015 health goal likelihood, ‘even though there might be differentials’ [Iv1564] as to what that one goal and its targets become.

The shift of post-2015 global health priorities beyond the MDG health silos

We further found most participants united over inclusion of two sub-goal priorities: ‘the unfinished MDG business’ and the inclusion of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (‘The kind of dark horse coming up the inside is NCDs. That is where the future is’ [Iv1588]; ‘NCDs are very important to a group of countries… because that’s where their disease burden is very clearly… And they would like something that addresses that’ [Iv1561]). Participants from diverse organizations spoke positively of the health MDGs and the need to ensure their achievement even beyond 2015. They also highlighted the next development agenda must not recreate a scenario where three health priorities overshadow all others:

The health MDGs were a success in mobilising global attention and resources, and in increasing the share of aid going to health. However, the specificity of the targets created several problems including over-emphasis on AIDS, and later malaria and TB, and neglect of other disease and health problems such as accidents and congenital conditions. The targets diverted resources away from hospitals and clinics towards disease campaigns. The multidimensional nature of health has been neglected [Iv1593]

Tension existed between completing the MDG agenda and avoiding the extension of what was perceived as the distortion of a limited number of targeted disease programs. Participants described how health’s framing in the sequence of post-2015 reports (i.e. ‘Maximizing Healthy Lives’ modification into ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ in May 2013) captures a shift away from the MDG era’s vertical approach: ‘[there is] a definite push with the post-2015 framework to come up with things that correct the past’ [Iv1568]. Respondents described this shift as a ‘pendulum swing’ or ‘backlash’, arguing it did not result from the health consultation but had dynamically evolved throughout the first decade of the 21st century: the shift reflects ‘backlash’ against ‘the decade of the noughties… [that] produced this kind of vertical approach’ [Iv1555], and the parallel biomedical, disease specific agenda it fostered. There was an implicit recognition that targeting single diseases to generate global support may be a strategy now paling from overuse: ‘It can’t be that every five years or every 10 years we just have a new kind of disease of the moment’ [Iv1556].

Tension around the nature of the one goal: a specific or comprehensive agenda

In discussing what the one post-2015 health goal might be, the responses of most participants were divided between either ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ as proposed by the High-Level Panel, or UHC, with slightly more participants supporting the former. Although the Sustainable Development Solution Network’s report was released in June 2013, after our interviews had commenced, no participants referred to its proposed goal ‘Achieving Health and Wellbeing at All Ages’, with its links to life phase strategies. Only a handful of participants were agnostic over which goal should dominate.

Whereas the High-Level Panel did not include UHC as one of ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ five targets, we found many participants who supported an ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ goal also supported UHC as an express sub-goal. Indeed, one participant conceptualized UHC as a ‘tool’ to achieve the ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ goal ‘vision’ [Iv1570]. However, the main argument in participants’ minds why UHC should not be the dominant goal was that it is not comprehensive enough, whereas ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ was viewed as more summative, with greater potential to facilitate inclusion of the social determinants of health.

UHC is not enough… to stop kids dying. A lot of things are not in UHC. Maternal education is not part of UHC… A lot of the preventive policies, water and sanitation, early child development, it’s not part of UHC… there are some people who will tell you that UHC includes action on social determinants, but in fact, while it might include action on social determinants… how does it include action on the broader determinants… What does it have to say about inter-sectoral action? That doesn’t seem to me intellectually credible [Iv1557]

Interestingly, only one participant supporting UHC clarified its link to the social determinants:

Clearly, when you’re talking about improving health conditions… going from prevention, promotion, treatment, control and treatment… The prevention and promotion part includes all the health determinants, so it’s not only how the services will respond with treatment. There it is too late and too costly [Iv1560]

However, others questioned the legitimacy of this framing, arguing UHC proponents were now inflating UHC for advocacy purposes: ‘now it seems it [UHC] is expanding into also prevention and also social determinants and any of the factors that help health’ [Iv1566]. Another maintained this expansion is misplaced, that there is need for a larger health systems conceptual framework, of which UHC was a limited part:

UHC can never replace a good understanding in terms of a conception model and a strategic way of working in terms of supporting health systems because you know if your health coverage is part of that… I mean, you can link everything to everything. But I wouldn’t say that – then we are mixing apples and pears [Iv1591]

Participants supporting ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ further argued the post-2015 health goal must transcend UHC’s limited focus on the health sector: ‘Its got to go beyond health services; there’s health service coverage but there’s also many other cross sectoral issues we’ve got to pick up, which I guess life expectancy does bring in, it makes some links to education, it makes some links to distribution… the behaviours that will go beyond as well’ [Iv1580]. For these respondents, the health goal must embrace strategies beyond the health sector: ‘[UHC] tells you nothing about major preventive interventions that can have a big impact on health like tobacco taxes and legislation. It’s very sectoral… it’s very much about curative services when you talk about UHC’ [Iv1568]. Although such respondents generally viewed UHC instrumental to the new health goal (‘It’s a very attractive concept that I don’t think anyone really in health has any problem with’ [Iv1557]), they often considered UHC did not and could not represent an overarching goal in itself, but rather health services as a sectoral investment:

Health is a lot more than just what the health system is doing. And we know this from the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health… the political declaration on NCDs says this, the UN General-Assembly Special Session stuff on AIDS says this, so we can’t just be looking at a health system response… And so people started thinking, well, what would a more appropriate goal look like, if it really isn’t just about the health system? And I think that’s where the Healthy Lives thing came out [Iv1557]

Perceptions that UHC lacks conceptual clarity and marketability

Participants articulated the complaint that UHC was unworkable as an umbrella health goal, largely because of its problematic definition: ‘Nobody knows what UHC is’ [Iv1557]; ‘What does it mean and where are resources coming? And what are the processes to build the system?’ [Iv1564]. Without a consistent definition, UHC’s ambiguity undermines its saleability to a wider audience. For one participant, this was UHC’s ‘nail in the coffin’ [Iv1565], while two others asserted this is the reason UHC was not included as a target by the High-Level Panel. UHC was not seen as communicating effectively at a popular level:

Do you tell your aunty—in the suburbs of Sydney: ‘Oh, yeah. We’ve got a campaign for UHC’? Or do you say, ‘we’re trying to maximise healthy lives’, politically? And I think the High-Level Panel did it quite well, where they said they chose to focus on health outcomes [Iv1569]

Given UHC’s prominence, its cursory mention in the High-Level Panel report was unexpected. For one UN-based participant, the High-Level Panel report writers did not critically consider UHC’s potential, with its very inclusion in the report an after-thought:

Literally two days before it was published… it didn’t have really anything on UHC at all, which is a major problem… to me that just was not the focus of the people who were drafting that report, and so they just did not give enough thought to what the global health community was saying. And then at the last minute when they realised they were going to get quite a bit of backlash from the global health community for not even talking about UHC, they weren’t even talking about social determinants, that was sort of added into the narrative, but they didn’t really make it into a target or goal [Iv1587]

However another UN-based participant alleges UHC was not included in the High-Level Panel’s goals/targets because the complexity of measuring its achievement confounded report drafters:

If you’re going to say you want a UHC goal and target what are the targets?… How would you name that and to say the target is, you know, access to services that people need at an affordable cost… that’s not specific enough… are you going to be funding Glivec for everyone in the world everywhere? [Iv1557]

Continuing claims for UHC, despite early post-2015 struggle

From the time the health consultation began in September 2012, UHC rose to underpin the UN Foreign Policy Resolution in December 2012 (UN General Assembly 2012). By April 2013, it was one of three key concepts in the Global Thematic Consultation on Health’s report; by the May 2013 High-Level Panel report, it was almost left out entirely from the illustrative goal framework. UHC’s promotion by WHO from 2010 had been deliberate; respondents recognized that its fall over a 6-month period (December 2012–May 2013) had been both swift and dramatic. The dramatic trajectory was a source of some bemusement: ‘It’s interesting to see how UHC has been repositioned’ [Iv1584]. From the perspective of informants present at the March 2013 Botswana meeting, this was the critical juncture for UHC: this meeting cemented UHC’s subservience to the favoured healthy life objective.

[In Botswana] it was quite a strong feeling… UHC is really important. And it is a process to get to healthy lives. It is not a goal, in itself. And, I think, probably what happened in Botswana, was that right view about what is a goal, as distinct from what steps to get to the goal, and that is where health cover was endorsed as an important process, but it is not the goal. [Iv1569]

Conversely, several participants express surprise UHC was not given more than a hurried mention in the High-Level Panel report, especially as in 2012 UHC ‘was getting a lot of air time’ [Iv1587]. One participant argues the High-Level Panel’s lack of focus on UHC is inconsistent with their emphasis on ending poverty:

When I saw the High-Level Panel report and they were talking about eradicating poverty, and it seemed to be one of the… main narrative threads, I kept thinking, well how can you not be talking about UHC in a really significant and linked way, when most people around the world say poor health and catastrophic illnesses are a major factor in driving them into poverty, liquidating assets et cetera, it would seem quite natural to me that UHC with its aspect of financial protection would be naturally integrated to that, naturally linked to that. But it hasn’t been made. It’s a little bizarre to me. [Iv1587]

Some participants felt there had been a pervading sense of inevitability within the global health community, especially in 2012, around UHC’s ‘logical progression’ [Iv1556] to transform into the post-2015 umbrella health goal. One participant reflected many believed UHC’s metamorphosis was a fait accompli: ‘there was a perception on the North-East as well that it was a done deal, it’s going to be UHC’ [Iv1557].

Although participants generally agree there will be considerable debate until implementation of the new goals on 1 January 2016, several participants anticipated UHC would gain traction in the second phase, with one participant suggesting UHC would transform into the overarching health goal in 2014 through the Member State led Open Working Group forum. This individual observed while support for UHC is not unqualified in the UN agencies, among Member States UHC receives strong endorsement, and it is the Member States who are the real post-2015 decision makers:

There is a group of countries that are very committed to UHC… countries that have already… made some progress toward that and they would like to see the rest of the world get there as well [Iv1561]

When you realise that… when these are reconciled… [post-2015 negotiations are] going to be done by national negotiators… in New York, and they’re going to be talking to their foreign ministries, to their health ministries… So you have the foreign policy in global health, the BRICS countries who made a statement this year in Geneva at the Assembly, and they said, “We want to work with WHO to ensure that the agency is able to monitor and measure UHC,” and their previous statement, they had a communiqué in January, where they recognised the resolution… I feel fairly optimistic that in the next 12 months… the Sustainable Development Solutions Network… will strongly focus on UHC, so we feel pretty optimistic [Iv1556]

A number of participants predict WHO and its Director-General will accelerate their UHC advocacy in the second negotiation phase, broadly agreeing it is not in WHO’s interests to allow UHC to fall off the post-2015 negotiation table. In many ways, UHC has become a metaphor for WHO’s political legitimacy:

‘it’s quite natural for the WHO to come up quite strong on UHC… for a variety of reasons that are sort of about their own existential issues, and where that [UHC] - and just what they do, that [UHC], is what the WHO is about.’ [Iv1587].

Nevertheless, UHC’s proponents consist of more agencies than WHO alone, with one participant describing UHC supporters as ‘a very organized… constituency’ whose ‘voices are very powerful and influential’ [Iv1557] at the global level.

Discussion

In the discussion of our findings we have used the Shiffman and Smith (2007) framework, modified by Benzian et al. (2011), and summarized in Table 3. This reframing of our findings into the power of the issue and the actors, the characteristics of the issues and the politics of the context provides a more structured extension of the policy triangle framework initially advocated by Walt and Gilson (1994).

Table 3.

Political analysis results of our findings on UHC’s location in the post-2015 health-goal agenda in June–July 2013 (see Benzian et al. 2011)

| Analysis category | Factors shaping political priority | Analysis of informant’s views on UHC in emerging post-2015 health goal discourse |

|---|---|---|

| Ideas: the ways in which those involved with the issue understand and portray it |

|

|

| Actor power: strength of the individuals and organizations concerned with the issue |

|

|

| Issue characteristics: features of the problem |

|

|

| Political contexts: The environments in which actors operate |

|

|

The power of ideas—confusion around UHC’s definition compromises its post-2015 framing

Framing ‘is an important communication tool used in advocacy and related to the way an issue is portrayed and communicated, both internally and externally’ (Benzian et al. 2011; and see Shiffman and Smith 2007). Our study reveals that at the June–July 2013 temporal juncture, persistent confusion around UHC’s meaning undermines its framing for post-2015 advocacy purposes. Participants contend this is a real stumbling block for getting UHC onto the post-2015 policy agenda, in terms of attracting political support for it to not only be considered a post-2015 health and development goal possibility, but also to be considered (at minimum) an express target within the health goal metric framework. Participants also consider the struggle for UHC’s supporters to offer measureable indicators to be a key framing flaw. WHO and the World Bank’s subsequent release in December 2013 of a potential framework for ‘measuring’ UHC at both country and global levels could be viewed as a response to UHC’s framing conundrum (see Vega and Frenz 2013; WHO and World Bank 2013; Obare et al. 2014).

Yet the global health community is not homogenous (Fidler 2007; Hill 2011), and any expectation that a substantial community would rally behind UHC’s integration in the post-2015 goal framework could be arguably naïve and ill-founded. Yet surprisingly, there is an apparent consensus among participants: coalescence is emerging around the content of the elements proposed for the health goals. No interviewees identified gaps in the health agenda—some questioned the defining of ‘selected’ NCDs and its implications, or the vulnerability of SRHR—but essentially the territory seems identified. There is consensus for the elements of the package but configuration of the package—of the headline goal and suite of secondary targets—remains contested.

The power of actors—UHC has disparate supporters offering disparate messages

Another reason behind UHC’s divisiveness in mid-2013 relates to the advocacy strategy (or lack of) by the actors involved. Concern exists among some respondents that piecemeal advocacy for UHC (lacking a cohesive message) is another iteration of the global health sector’s hubris and insular presumption. This relates to concern global health academics and UHC advocates continue to talk to other academics and advocates, ignoring the comprehensive nature not only of the goal (or sub-goal) they seek to embed, but of the universal, cross-sectoral post-2015 goal agenda and its multiple stakeholders (Hill et al. 2014). Participants anticipate a number of States will emerge as strong UHC supporters (but do not identify these), as with WHO, but at the time our interviews were conducted in June–July 2013 question remains as to whether the efforts of these actors will provide UHC with enough cohesive support to make it over the line on 1 January 2016.

Indeed, as of mid-2013, UHC’s scale back within the High-Level Panel report proves its vulnerability: that is, even though it is the preferred goal of a UN agency (the WHO) in a UN-led post-2015 consultative process, it still was unable to attract explicit support to ensure its inclusion as a goal or target in the High-Level Panel report. This leads to question around WHO’s political power in shaping the emergent post-2015 health goal discourse. WHO’s subsequent release of UHC governance and measurement action plans in 2014 and 2015 (the latter in partnership with the World Bank) arguably evidences this agency’s renewed strategic interplay in Member State post-2015 health goal discussion (WHO and World Bank 2013, 2014, 2015; WHO 2014).

The range of UN positions in June–July 2013 in terms of health goal advocacy was surprisingly broad. WHO clearly promoted UHC as its preferred goal, though SRHR advocates within WHO were concerned to see this agenda retained prominence, and others saw the importance of an agenda that spoke more broadly to sustainable development. Beyond WHO, support for UHC as a primary goal was equivocal—with the exception of one key civil society organization—though most advocated its inclusion, if not as a goal, as a mechanism for achieving the goals. When our interviews were held in mid-2013 some UN agencies conceded they were not interested in championing specific goals but vigilant to ensure their mandated interests were covered. Those committed to UHC, confronted by its apparent slippage in the High-Level Panel document, flagged commitment to challenge this in 2014, addressing the difficulties in measuring UHC outcomes and harnessing country support to promote its significance.

The intergovernmental Open Working Group for Sustainable Development’s (2014) release of its proposed post-2015 goals and targets in May 2014, expressly including achievement of UHC as one of 10 targets beneath its suggested ‘Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’ goal, provided hope for UHC proponents. UHC’s inclusion as a suggested target further realizes study participant’s anticipation of government backing for UHC’s inclusion. This was bolstered in early 2015 by a call from the Prince Mahidol Award Conference to change the SDG health goal to ‘Progressively achieve UHC and ensure healthy lives for all’, with the apparent support of the Thai hosts, and sponsors including WHO, the World Bank, JICA, USAID, China Medical Board and the Rockefeller Foundation (Prince Mahidol Awards Conference 2015). The weight of global health commentary in linking UHC and the post-2015 agenda reiterates debate that UHC should not be discounted from the post-2015 negotiation table (Brearley et al. 2013; Campbell et al. 2013; Evans et al. 2013; Fried et al. 2013; Klingen 2013; Kruk 2013; Vega 2013; Vega and Frenz 2013; Minh et al. 2014; Clark 2014a; Sambo and Kirigia 2014; Tangcharoensathien et al. 2015).

Yet UHC’s location as a target in the final health goal proposal before the UN General Assembly in September 2015 highlights that despite the weighty Prince Mahidol Award Conference’s advocacy efforts for UHC to become the overarching health SDG, its framing as a target within the intergovernmental Open Working Group’s proposal was ultimately maintained (UN General Assembly 2015). Whether this is a secondary framing will depend on two elements. First, the content of this target’s indicators to be developed after the September 2015 General Assembly vote in early 2016 (IISD 2015). And second, once UHC’s indicators have been established, how seriously committed the UN Member States are in implementing the UHC target, and supporting other UN Member States to do the same.

The power of the issue—why care whether UHC becomes the post-2015 health goal?

For UHC’s supporters it may seem obvious not only what UHC means but why it is important that UHC becomes the post-2015 health goal, or at least an underlying target. However this obviousness did not translate into UHC’s uptake in the emergent post-2015 health goal agenda in mid-2013, as highlighted by its absence in the High-Level Panel’s proposed health goal and targets, and then by its position as an underlying target in the Open Working Group’s proposed health goal of May 2014. Confusion over UHC’s definition seriously hampers the effective framing of messages and arguments for UHC in the post-2015 context. Yet if the global health community (or its elements) cannot agree on (and thus rally around) a common understanding of UHC; then how UHC can be expected to appeal to a broader audience. Why should a broader audience care? With this in mind, some might argue UHC advocates are fortunate UHC was included at all by Member States as one of the many proposed global health goal targets.

Furthermore, our findings indicate UHC’s advocates may not be offering the indicators required for its uptake on the post-2015 health goal agenda. Our study shows that, once again, as in the MDG framework, a SDG framework explicitly linked to goals, targets and indicators ‘matters’. Yet UHC indicators are in development (e.g. WHO/World Bank proposal of December 2013), will not be finalized before 2016, and do not always marry or connect directly with the indicators to monitor progress of the three health-related MDGs. Our study participants offer strong support for continuing the unfinished business of the MDGs in the post-2015 health and development environment, and implicitly the same goal-target-indicator structure. Moreover, UHC indicators are not yet fully integrated ‘into the general health indicator framework that is used and accepted by health decision makers, such as the disability-adjusted-life-years (DALY) concept’ (Benzian et al. 2011), which has been adapted since 2001 to overlay the health MDGs’ vertical approach. Moreover, without this established evidence-base, UHC’s advocates cannot contend their arguments are grounded within the science, or that they are thus cost-effective. Thus how the UHC indicators are framed in early 2016 will be imperative.

The power of political context—initiating, using and strategically foreseeing opportunities for UHC advocacy

Participants in our mid-2013 study highlight UHC experienced a rapid depression in its framing in the post-2015 context after its rise through the General Assembly’s Global Health and Foreign Policy resolution at the end of 2012 (see UN General Assembly 2012). Our participants indicate not only was this depression unexpected for UHC’s post-2015 proponents, but that such proponents may not have effectively used the window of opportunity opened by global momentum surrounding the December 2012 resolution in swiftly ensuing post-2015 debate. Indeed, UHC’s lack of expression within the High-Level Panel’s May 2013 illustrative health goal and its five targets, and its supporters’ surprise, is reminiscent of the SRHR’s community’s astonishment at SRHR’s sidelining from the MDGs following the outcomes of the broadly endorsed ICPD+5 Year Review in 1999 (Brolan and Hill 2014).

Our finding of unilateral acceptance of only one post-2015 health goal in mid-2013 presents a conundrum. It hardly reflects passivity in the global health community’s engagement in post-2015 debate—this heterogeneous sector was enormously energetic in the Global Thematic Consultation on Health, evidenced by both the quality and quantity of submissions. The sector’s active engagement is also visible in the amassing body of post-2015 global health literature. Yet respondents’ unanimous concession there will only be one post-2015 health goal is surprising in terms of the global health community’s negotiating position: in the early post-2015 consultation phase, before outright State negotiations begin, there was already pervasive and somewhat impassive acceptance that health would receive one goal only. This could be interpreted as relief that health was included, given its late inclusion in the Rio+20 Conference’s outcome document (Eliasz et al. 2013), and absence from the original proposal. One current rhetorical position held that perhaps health had been fortunate to obtain focus (and corresponding resources) through three of the eight MDG, and now other agendas deserved prominence (Dybul et al. 2012).

But what was clear from the debate over the summative health goal in our study in June–July 2013 was the expectation that this choice must embrace an ‘expanded’ agenda in health. At the time of these interviews, this conceded single health goal already embodied substantially more sub-agendas than those framed within the MDGs. In the debate in 2013, health retained the substance of the three health MDGs, but complemented these with approaches to selected NCDs, neglected tropical diseases, an extended SRHR and UHC implicitly—or explicitly—underpinning them. Advocates for UHC saw its systems framing providing that structure; the ‘healthy lives’ alternatives acknowledged UHC as a ‘means’, but set up an outcomes framework that measured individual health outcomes (and at different life stages), with the targets fractured into specific and measurable disease control.

Adding to this puzzle is our finding that although participant’s wanted a comprehensive global health goal, the majority nevertheless supported the High-Level Panel’s more summative vision for health ascribed in the ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ goal. The contradiction here is while the MDG agenda appears to be maintained and expanded in the High-Level Panel’s proposed imagining of the post-2015 development goal world, there is only one health goal embodying this extended schema. Moreover, if the UN Secretary General, similar to our participants, seeks ‘A Life of Dignity for All’ and a ‘universal agenda’ containing ‘vision and transformative actions’ (UN General Assembly 2013), how can this vision be actualized if the ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ goal only focuses on and benefits some through the elevation of certain health priorities? This is where the confusion lies: On the one hand participants strive to move beyond the old framing of global health silos, yet many implicitly endorse the High-Level Panel’s vertical approach to health, which is an expansion of the MDG agenda.

Conclusion

This study found at mid-2013 political priority for UHC in the post-2015 health goal context is low. Yet this low prioritization in the early stages of the post-2015 SDG discussion did not mean its ultimate exclusion from the health goal framework, as seen by its incorporation as a target in the final health SDG for UN General Assembly vote in September 2015 (UN General Assembly 2015).

If debate over a UHC and/or ‘Ensure Healthy Lives’ goal has marked a post-2015 tension, then this could be a proxy for broader global health debates; perhaps an iteration of the historical division between Selective Primary Health Care and Comprehensive Primary Health Care (Rifkin and Walt 1986; Walt and Gilson 1994) or related discourse around the global health agenda’s oscillating ‘medicalization’ (Clark 2014b). Although this study located echoes of the long-standing comprehensive-selective debates, the current formulation of health goals on the post-2015 negotiation table do not easily fit these constructions. For instance, ‘Ensure Healthy Lives at All Ages’ gives the appearance of comprehensiveness, but the implicit focus on measurement leads it easily to targeted approaches—the diseases of infancy, of childhood, of adolescence, of adult women, of adult men, of the aged (etc), with a specific list within each. UHC is similarly challenged: as participants within our study suggest, UHC’s proponents are reshaping it to meet the perceived demands of those post-2015 advocates (like the Gates Foundation) who are supportive of targeted approaches. The finance focus within UHC also risks a default position that neglects access and coverage, as well as quality and extensiveness, of health care and related services. For UHC to be comprehensive and equitable it must invoke the epistemic and the normative; it needs to be grounded in the human right to health.

Funding

This analysis was undertaken as part of Go4Health, a research projected funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, grant HEALTH-F1-2012-305240, and by the Australian Government’s NH&MRC-European Union Collaborative Research Grants, grant 1055137.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J, Marteau T. 1997. The Place of Inter-Rater Reliability in Qualitative Research: An Empirical Study. Sociology 31: 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling J. 2001. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 1: 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes A, Wallace Brown G. 2011. The Idea of Partnership within the Millennium Development Goals: context, instrumentality and the normative demands of partnership. Third World Quarterly 32: 165–80. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsworth R. 2011. Cosmopolitanism and International Relations Theory. Cambridge, UK: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Benzian H, Hobdell M, Holmgren C, et al. 2011. Political priority of global oral health: an analysis of reasons for international neglect. International Dental Journal 61: 124–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlan D, Buse K, Shiffman J, Tanaka S. 2014. The bit in the middle: a synthesis of global health literature on policy formulation and adoption. Health Policy and Planning 29: iii23–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brearley L, Marten R, O’Connell T. 2013. Universal health coverage: a commitment to close the gap. Save the Children. www.savethechildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/docs/Universal_health_coverage_0.pdf, accessed 29 November 0213.

- Brolan CE, Hill PS. 2014. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in the evolving post-2015 agenda: perspectives from key players from multilateral and related agencies in 2013. Reproductive Health Matters 22: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. 2005. Making Health Policy. Berkshire, England: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Buchan J, Cometto G, David B, Dussault G. 2013. Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91: 853–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. 2008. Return to Alma-Ata. The Lancet 372: 865–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek J. 2004. At the margins? Discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research 14: 1140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaruzzi M. 2012. Chapter 2: Realism. In: Devetak R, Burke A, George J. (eds). An Introduction to International Relations, 2nd edn. New York: Cambridge University Press, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. 2014a. Medicalization of global health 4: the universal health coverage campaign and the medicalization of global health. Global Health Action 7: 24004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. 2014b. Medicalization of global health 1: has the global health agenda become too medicalized? Global Health Action 7: 23998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens MA, Kenny CJ, Moss TJ. 2007. The Trouble with the MDGs: Confronting Expectations of Aid and Development Success. World Development 35: 735–51. [Google Scholar]

- Darrow M. 2012. The millennium development goals: milestones or millstones? Human rights priorities for the post-2015 development agenda. Yale Human Rights and Development Law Journal 15: 55–127. [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB. 2008. The turn in recent economics and return to orthodoxy. Cambridge Journal of Economics 30: 183–226. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle MW. 2011. Dialectics of a global constitution: The struggle over the UN Charter. European Journal of International Relations 18: 601–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dybul M, Piot P, Frenk J. 2012. Reshaping Global Health. Policy Review 173: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasz MWK, Deplante N, Boel A, Makuka GJ, Williams KG, et al. 2013. The position of health in sustainable development negotiations: a survey of negotiators and review of post-Rio+20 processes. The Lancet 381: 16. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DB, Hsu J, Boerma T. 2013. Universal health coverage and universal access. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91: 546–546A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyben R. 2006. The Road not Taken: international aid’s choice of Copenhagen over Beijing. Third World Quarterly 27: 595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Fehling M, Nelson BD, Venkatapuram S. 2013. Limitations of the millennium development goals: a literature review. Global Public Health 8: 1109–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D. 2007. Architecture amidst Anarchy: Global Health’s Quest for Governance. Global Health Governance 1 http://www.ghgj.org/Fidler_Architecture.pdf, accessed 14 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fried ST, Khurshid A, Tarlton D, et al. 2013. Universal health coverage: necessary but not sufficient. Reproductive Health Matters 21: 50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Thematic Consultation on Health. 2013. Health in the Post-2015 Agenda. The World We Want. https://www.worldwewant2015.org/health, accessed 14 July 2014.

- High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda (High-Level Panel). 2013. A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies Through Sustainable Development. http://www.un.org/sg/management/pdf/HLP_P2015_Report.pdf, accessed 14 July 2014.

- Hill PS. 2011. Understanding global health governance as a complex adaptive system. Global Public Health 6: 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PS, Buse K, Brolan CE, Ooms G. 2014. How can health remain central post-2015 in a sustainable development paradigm? Globalization and Health 10: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton R, Mullan Z. 2015. Health and sustainable development: a call for papers. The Lancet Global Health 3: e311–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme D. 2007. The Making of the Millennium Development Goals: Human Development Meets Results-based Management In an Imperfect World. The University of Manchester Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI) Working Paper 16. Manchester, England: The University of Manchester Brooks World Poverty Institute. http://www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/publications/working_papers/bwpi-wp-10009.pdf, accessed 14 July 2014.

- Hulme D. 2009a. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): A Short History of the World’s Biggest Promise. Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI) Working Paper 100. Manchester, England: The University of Manchester Brooks World Poverty Institute. http://www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/publications/working_papers/bwpi-wp-10009.pdf, accessed 25 May 2015.

- Hulme D. 2009b. Politics, Ethics and the Millennium Development Goals: The Case of Reproductive Health. Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI) Working Paper 104. Manchester, England: The University of Manchester Brooks World Poverty Institute. http://www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/publications/working_papers/bwpi-wp-10509.pdf, accessed 25 May 2015.

- Hulme D, Scott J. 2010. The Political Economy of the MDGs: Retrospect and Prospect for the World's Biggest Promise. Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI) Working Paper 1110. Manchester, England: The University of Manchester Brooks World Poverty Institute. http://www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/publications/working_papers/bwpi-wp-11010.pdf, accessed 9 June 2015.

- Hyatt D. 2005. Time for a change: a critical discourse analysis of synchronic context with diachronic relevance. Discourse and Society 16: 514–34. [Google Scholar]

- IISD 2015. Post-2015 Negotiations Take up Indicator Framework. International Institute for Sustainable Development. http://sd.iisd.org/news/post-2015-negotiations-take-up-indicator-framework/, accessed 16 September 2015.

- Jones R. 2013. ‘Too many cooks in the kitchen,’ warns MDG co-architect. Devex. https://www.devex.com/news/too-many-cooks-in-the-kitchen-warns-mdg-co-architect-80799, accessed 23 April 2014.

- Keeling A. 2012. Using Shiffman’s political priority model for future diabetes advocacy. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 95: 299–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JR, McGrath JE. 1988. On time and Method. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Obara H, Takashima Y, et al. 2013. World Health Assembly Agendas and trends of international health issues for the last 45 years: analysis of World Health Assembly Agendas between 1970 and 2012. Health Policy 110: 198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingen N. 2013. Universal health coverage: a movement gains steam. Blogs.worldbank.org (March 4). http://blogs.worldbank.org/health/universal-health-coverage-a-movement-gains-steam, accessed 29 November 2013.

- Kruk ME. 2013. Universal health coverage: a policy whose time has come . British Medical Journal 347: f6360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn JE, Rohde J, Rifkin S, et al. 2008. Alma-Ata 30 years on: revolutionary, relevant, and time to revitalise. The Lancet 372: 917–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton D. 1992. Discourse analysis: a new methodology for understanding the ideologies of health and illness. Australian Journal of Public Health 16: 145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning S. 2009. DIIS Report. Using Indicators to Encourage Development. Lessons from the Millennium Development Goals. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Mays N, Pope C. 1995. Rigour and qualitative research. British Medical Journal 311: 109–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken J. 1999. The study of discourse in international relations: a critique of research and methods. European Journal of International Relations 5: 225–4. [Google Scholar]

- Minh HV, Pocock NS, Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. 2014. Progress toward universal health coverage in ASEAN. Global Health Action 7: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obare V, Brolan CE, Hill PS. 2014. Indicators for Universal Health Coverage: can Kenya comply with the proposed post-2015 monitoring recommendations? International Journal for Equity in Health 13: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL. 2007. A Call for Qualitative Power Analyses. Quality and Quantity 41: 105–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ooms G, Brolan C, Eggermont N, et al. 2013. Universal health coverage anchored in the right to health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91: 2–2A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooms G, Latif LA, Waris A, et al. 2014. Is universal health coverage the practical expression of the right to health care? BMC International Health and Human Rights 14: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Open Working Group for Sustainable Development. 2014. Zero Draft – Rev 1. Introduction and Proposed Goals and Targets on Sustainable Development for the Post 2015 Development Agenda. http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/focussdgs.html, accessed 14 July 2014.

- Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Gervais S, et al. 2012. Nutrition agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation: lessons from the Mainstreaming Nutrition Initiative. Health Policy and Planning 27: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince Mahidol Awards Conference. 2015. Conference Synthesis: Summary & Recommendations. http://www.pmaconference.mahidol.ac.th/, accessed 7 June 2015.

- Rengger N. 2014. Pluralism in international relations theory: three questions. International Studies Perspectives 16: 32–9. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson V. 1992. The agenda-setting dilemma in a constructivist staff-development process. Teaching and Teacher Education 8: 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin SB, Walt G. 1986. Why health improves: defining the issues concerning ‘Comprehensive Primary Health Care’ and ‘Selective Primary Health Care’. Social Science and Medicine 23: 559–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saith A. 2006. From universal values to millennium development goals: lost in translation. Development and Change 37: 1167–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sambo LG, Kirigia JM. 2014. Investing in health systems for universal health coverage in Africa. BMC International Health and Human Rights 14: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. 1999. Time and qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health 22: 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Joosen I, Kunst AE, Klazinga NS, Stronks K. 2010. Generating political priority to tackle health disparities: a case study in the Dutch city of the Hague. American Journal of Public Health 100: Suppl. IS210–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman J, Smith S. 2007. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. The Lancet 370: 1370–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman J, Beer T, Wu Y. 2002. The emergence of global disease control priorities. Health Policy and Planning 17: 225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks H, Brown Trinidad S. 2007. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research 17: 1372–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Mills A, Palu T. 2015. Accelerating health equity: the key role of universal health coverage in the Sustainable Development Goals. BMC Medicine 13: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Lund C. 2012. Why does mental health not get the attention it deserves? An application of the Shiffman and Smith framework. PLoS Medicine 9: e1001178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. 2003. Human Development Report 2003 Millennium Development Goals: A Compact among Nations to end Human Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. 2012. Global Health and Foreign Policy [resolution]. New York: United Nations; http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/67/L.36&referer=http://www.un.org/en/ga/info/draft/index.shtml&Lang=E, accessed 10 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. 2013. A life of dignity for all: accelerating progress towards the Millennium Development Goals and advancing the United Nations development agenda beyond 2015. Report of the Secretary-General. A/68/202. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/A%20Life%20of%20Dignity%20for%20All.pdf, accessed 29 November 2013.

- UN General Assembly. 2015. Draft outcome document of the United Nations summit for the adoption of the post-2015 development goals. Draft resolution submitted by the President of the General Assembly. A/69/L.85. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/69/L.85&Lang=E, accessed 16 September 2015.

- UN System Task Team. 2012. Realizing the Future We Want for All: Report to the UN Secretary-General. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 2001. Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations Millennium Declaration: Report of the Secretary General. A/56/326. New York: United Nations. http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/a56326.pdf, accessed 14 July 2014.

- Vandemoortele J. 2005. Ambition is golden: meeting the MDGs. Development 48: 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vandemoortele J. 2011a. The MDG story: intention denied. Development and Change 42: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vandemoortele J. 2011b. If not the millennium development goals, then what? Third World Quarterly 32: 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vandemoortele J. 2013. Chapter 2: A fresh look at the MDGs. In: Clarke M, Feeny S. (eds). Millennium Development Goals: Looking Beyond 2015. US: Routledge, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vega J. 2013. Universal health coverage: The post-2015 development agenda. The Lancet 381: 179–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega J, Frenz P. 2013. Integrating social determinants of health in the universal health coverage monitoring framework. Pan American Journal of Public Health 34: 468–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waage J, Banerji R, Campbell O, et al. 2010. The millennium development goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015: Lancet and London International Development Centre Commission. The Lancet 376: 991–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Gilson L. 1994. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning 9: 353–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Gilson L. 2014. Can frameworks inform knowledge about health policy processes? Reviewing health policy papers on agenda setting and testing them against a specific priority-setting framework. Health Policy and Planning 29: iii6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H, Black R. 2004. Millennium development goals a drop in the ocean? In: White H, Black R. (eds). Targeting Development: Critical Perspectives on the Millennium Development Goals. UK: Routledge, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2014. Health Systems Governance for Universal Health Coverage: Action Plan. http://www.who.int/universal_health_coverage/plan_action-hsgov_uhc.pdf, accessed 16 September 2015.

- World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank. 2013. Monitoring Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage at Country and Global Levels: A Framework. Joint WHO/World Bank Group Discussion Paper (December). http://www.who.int/healthinfo/country_monitoring_evaluation/UHC_WBG_DiscussionPaper_Dec2013.pdf, accessed 14 July 2014.

- World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank. 2014. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels: framework, measures and targets. Joint WHO/World Bank Group report (May). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112824/1/WHO_HIS_HIA_14.1_eng.pdf, accessed 16 September 2015.

- World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank. 2015. Tracking universal health coverage: First global monitoring report. Joint WHO/World Bank Group report (June). http://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/2015/en/, accessed 16 September 2015.

- Yamin AE, Boulanger VM. 2013. Embedding sexual and reproductive health and rights in a transformational development framework: lessons learned from the MDG targets and indicators. Reproductive Health Matters 21: 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]