Abstract

Spruce wood specimens were bonded with one-component polyurethane (PUR) and urea-formaldehyde (UF) adhesive, respectively. The adhesion of the adhesives to the wood cell wall was evaluated at two different locations by means of a new micromechanical assay based on nanoindentation. One location tested corresponded to the interface between the adhesive and the natural inner cell wall surface of the secondary cell wall layer 3 (S3), whereas the second location corresponded to the interface between the adhesive and the freshly cut secondary cell wall layer 2 (S2). Overall, a trend towards reduced cell wall adhesion was found for PUR compared to UF. Position-resolved examination revealed excellent adhesion of UF to freshly cut cell walls (S2) but significantly diminished adhesion to the inner cell wall surface (S3). In contrast, PUR showed better adhesion to the inner cell wall surface and less adhesion to freshly cut cell walls. Atomic force microscopy revealed a less polar character for the inner cell wall surface (S3) compared to freshly cut cell walls (S2). It is proposed that differences in the polarity of the used adhesives and the surface chemistry of the two cell wall surfaces examined account for the observed trends.

Keywords: Adhesives for wood, Interfaces, Dynamic mechanical analysis, Wood

1. Introduction

The mechanical characterisation of adhesion is of utmost importance in order to evaluate differences in the performance of adhesives. On the one hand, mechanical experiments can be performed in a relatively straightforward manner with comparably homogeneous materials such as metals or polymers. On the other hand, the mechanical characterisation of adhesion in a heterogeneous, porous, and hierarchically structured material like wood poses a serious challenge with regard to the correct interpretation of results. Current testing standards such as [1] and similar international standards rely predominantly on shear testing (lap-shear or block-shear) and delamination testing with and without pre-treatment by moisture, heat, and combinations thereof. In an application-oriented context, these methods deliver useful and reliable results on adhesive performance. However, in a more scientific context, results obtained using standardised tests are often difficult to interpret due to the complex microstructure of the involved material (e.g. [2]). In particular, the nature of the interface between wood and an adhesive, which consists of neat adhesive and neat wood, and a zone where wood and adhesive interpenetrate, makes it difficult to track down the point of initiation of failure. In an effort to obtain information on the practical adhesion directly at the interface between the wood cell wall and an adhesive polymer and thus avoiding effects originating from surface roughness and adhesive penetration at the micron-scale, a modified nanoindentation test was introduced recently [3]. It was demonstrated that the total energy spent in an indentation experiment directly at the interface between the wood cell wall and urea-formaldehyde adhesive was related to the strength of adhesion between the two partners, i.e. the required indentation energy increased with increasing adhesive bond strength. In the present study, this new micromechanical assay is used to investigate the adhesion of one-component polyurethane (PUR) and urea-formaldehyde-based adhesive (UF), to wood surfaces on the cell wall level.

PUR and UF belong to two groups of wood adhesives which differ significantly in their chemistry, structure-property and wood–adhesive interaction relationships [4]. PUR may be classified as pre-polymerised adhesive with large average molecular weight components. However, depending on the specific type of PUR, a wide distribution of properties is possible [5]. UF on the other hand belongs to the group of in-situ polymerised adhesives. It is characterised by a broad distribution of molecular weight fractions, high hydrophilicity and ability to penetrate into the wood cell wall, resulting in significantly altered mechanics of cell walls next to the adhesive [6], [7], [8]. In its cured state, PUR usually is comparably soft and ductile, whereas UF may be characterised as hard and brittle [9]. The strong interpenetration between wood and adhesive both at the cell-cavity and the cell-wall scales typical of in-situ polymerised resins such as UF results in a dominance of cohesive failure in neat wood next to the bond line (wood failure, Fig. 1). Since in this case the adhesive bond line appears to be stronger than solid wood, a high proportion of wood failure is considered an indicator for high bond durability. In this context, the failure pattern of most PURs differs significantly, since the percentage of wood failure is often low (Fig. 1), specifically after moisture treatment, even if a high shear strength is retained [10].

Fig. 1.

Typical patterns of bond line failure in delamination testing. Left: failure occurs in neat wood next to the bond line (cohesive wood failure). Right: failure occurs by delamination between wood and adhesive (adhesion failure).

Applying a newly developed micromechanical assay the present study aims at obtaining new information on the interaction of PUR and the wood cell wall compared to UF. Results of such experiments are expected to help with interpretation of the particular behaviour of PUR in the adhesive bonding of wood. As the main aim is the application and presentation of the method rather than giving a full presentation of differing properties of adhesives, only one commercially available PUR- and UF-adhesive is tested, respectively, and only on spruce wood samples.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

Norway spruce (Picea abies) samples from different parts in the stem were impregnated with water for several days in order to soften them prior to microtoming. By means of a conventional sledge microtome equipped with a steel knife, a smooth surface was cut along the tangential anatomical plane parallel to the direction of wood fibres. After that, samples were dried and stored in standard climate for several days before they were bonded with a one-component polyurethane adhesive (PUR, Purbond HB S309, Purbond AG, Switzerland) and urea-formaldehyde-based adhesive (UF, W-Leim Spezial, Dynea, Austria), respectively. After curing at ambient conditions, nanoindentation (NI) specimens were prepared from small pieces of wood containing the adhesive bond line. Cross sections normal to the direction of wood fibres were cut without prior embedding in epoxy resin using a diamond knife on an ultramicrotome (Leica) to provide smooth indentation surfaces. During each step of sample manipulation, special care was given to the fibre orientation in order to ensure that the final plane of indentation was normal to the fibre direction.

2.2. Nanoindentation

All NI experiments were performed on a Hysitron nanoindenter using a cone shaped diamond tip with a total opening angle of 60° and a tip radius of 10 nm. As load function, a linear four-step displacement controlled function with a quadratic increase of peak displacement from step to step and partial unloading after each step to half peak displacement was chosen as it yielded the best results in a comparison of various load functions. The implementation of load–partial unload cycles slows down the indentation process, thus allowing for deformation to follow the path of least resistance while still allowing for relatively fast indentation speed so as to reduce creep deformation during the load phase. Displacement control is necessary to provide the same total deformation for all samples, therefore giving a means of comparing indentation energies. Indents were performed at the interface between the adhesive and the wood cell wall at positions shown in Fig. 2. A first set of indents was taken at the (natural) inner surface of the cell wall (P1), corresponding to the secondary cell wall layer 3 (S3). A second set was performed at the (artificial) surface created by cutting through the cell wall in the process of surface preparation (P2). This surface corresponds to the cut-open surface of the secondary cell wall layer 2 (S2). The precise positioning of indents was performed on 15 μm×15 μm scanning probe micrographs taken with the indenter tip. For all indents, care was taken that in an area of approximately 5 μm radius no pre-damage, be it from sample preparation or other indents, was visible. The indentation energy for each indent was calculated as the numeric integral of the force–displacement curves (F–d curves). As demonstrated in [3], the principle underlying the evaluation of indentation energy is that there is a contribution of adhesion to the total indentation energy at the cell wall–adhesive interface. Thus e.g. diminishing adhesion will result in diminishing total indentation energy.

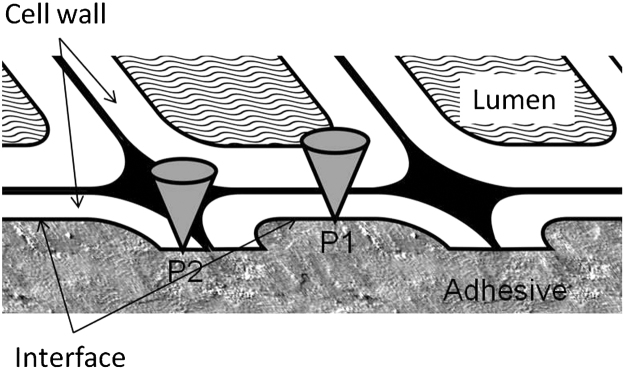

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of indent positions at the cell wall–adhesive interface. Position 1 (P1) is located at the natural inner surface of the cell cavity. Position 2 (P2) is located at the artificial cell wall surface cut-open in the process of wood surface preparation. To prevent artefacts, indents were only performed in areas of at least 5 μm radius without visible damage or further interfaces. This implicates that only latewood cells were tested.

2.3. Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

In order to obtain additional information on the processes taking place during an indentation experiment at the wood cell wall–adhesive interface, in particular the eventual formation of cracks, a number of residual indents in both UF- and PUR-bonded samples were scanned with an AFM one day after indenting. All images were taken on a Dimension Icon AFM (Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA) in tapping mode. The tips were mounted on standard silicon cantilevers with a resonance frequency of 330–340 kHz and a nominal tip radius of less than 12 nm. Images taken were 2 μm in size with a standard drive frequency of 0.7 lines per second. Gain factors and amplitude settings were adjusted for each scan but were of comparable values for all scans. Using software provided by the manufacturer, topography images were inverted for easier viewing and x–z-data parallel and normal to the bond line through the indent peak was analysed in order to obtain characteristic indent profiles.

With the aim of characterising possible differences in the polarity of the cell wall surface at the two indentation positions (P1 and P2 according to Fig. 2) chosen, chemical force microscopy was performed using untreated silicon tips on a silicon nitride cantilever. The system measures the adhesion by performing small indents at every point of the scan and evaluating the load–unload curves. The force required to detach the tip from the indented surface corresponds to adhesion and depends on the surface chemical characteristics of the surface and the tip, respectively. Indent depths varied between 30 nm and 50 nm with scan rates ranging from 0.5 to 1 Hz. The cantilever stiffness was measured by thermal tuning and was about 0.4–0.5 N/m for varying tips. The nominal tip radius was 2 nm, however it was not known or measured exactly which is why results were evaluated only qualitatively. To obtain a qualitative evaluation of the tip polarity, a model system consisting of a lyocell fibre (100% cellulose, polar) embedded in epoxy (unpolar) was scanned with the same settings.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Comparison of PUR and UF

The results of indentation experiments are shown as representative mean F–d curves in Fig. 3. Overall, a much higher peak force is required to reach a desired displacement with UF than with PUR. This significant difference may be well explained by the higher stiffness of the UF as compared to the PUR [9] and the penetration of the UF into the cell wall [6], leading to an effectively increased stiffness of the total cell wall–adhesive system. It is thus proposed that the composite cell wall–UF poses more resistance towards indentation compared to the cell wall–PUR composite.

Fig. 3.

Mean force–displacement (F–d) curves for all indent series. While the target displacement is the same for all sets of indents, significantly different force was required to achieve the desired displacement.

It is an important prerequisite for the determination of adhesive energy using the present method that the stiffness of the systems considered remains unchanged [3]. Due to the clear difference in stiffness by a factor in the order of 10 between UF and PUR [9], it is not possible to draw global conclusions on eventual differences in adhesion between wood and UF or PUR, respectively, from results shown in Fig. 3, however, an inspection of residual indents from experiments performed at the cell wall–adhesive interface by means of AFM (Figs. 4 and 5) reveals small differences in indent geometry which may be interpreted in terms of adhesion. Indents at the cell wall–UF interface shown in Fig. 4 nicely depict the geometry of the conical indenter. The profile of the indent peak is the same regardless whether a section parallel or normal to the interface is considered. This may be interpreted as a sign of relatively good adhesion, since a similar amount of plastic deformation has occurred parallel to the interface and also normal to it. In contrast, this symmetry is not observed in indents at the cell wall–PUR interface (Fig. 5). Here, the residual indent peak is significantly wider and less sharp parallel to the interface than normal to it. The asymmetry in the profile normal to the interface shown in Fig. 5a can be explained by the slight displacement of the indent towards the adhesive. The indent eventually reaches the interface and leads to delamination as well as the asymmetry. However, such slight misplacements were not found to lead to significant deviations in the work of indentation. It remains true that the actual indent peak however is much sharper normal to the interface than parallel to it, indicating that plastic deformation more easily takes place along the interface than transverse to it. It seems that the interface is a point of weakness in the system cell wall–PUR, which is apparently not in the system cell wall–UF. This may be attributed to the penetration of the UF into the cell wall [6], leading to a more homogenous mechanical system with a less well defined interface. In terms of adhesion one may conclude that overall the direct interfacial adhesion to wood is weaker for PUR than for UF. Of course, this may not necessarily translate to reduced macroscopic bond durability, since the latter is a result of additional factors such as e.g. effects of surface roughness and cell lumen or cell-wall penetration [4]. At least, the lack of wood failure observed for PUR in certain testing regimes [10] may have its origin in a measurable weakness of adhesion at the interface with the cell wall.

Fig. 4.

Inverted AFM-scans of interfacial indents on the UF-bonded sample (above) at P2 (a) and P1 (b). Section data was taken normal and parallel to the bond line at the indent peak (below).

Fig. 5.

Inverted AFM-scans of interfacial indents on the PUR-bonded sample (above) at P2 (a) and P1 (b). Section data was taken normal and parallel to the bond line at the indent peak (below).

3.2. Comparison of adhesion to the natural inner cell wall surface (S3) and to cut-open cell walls (S2)

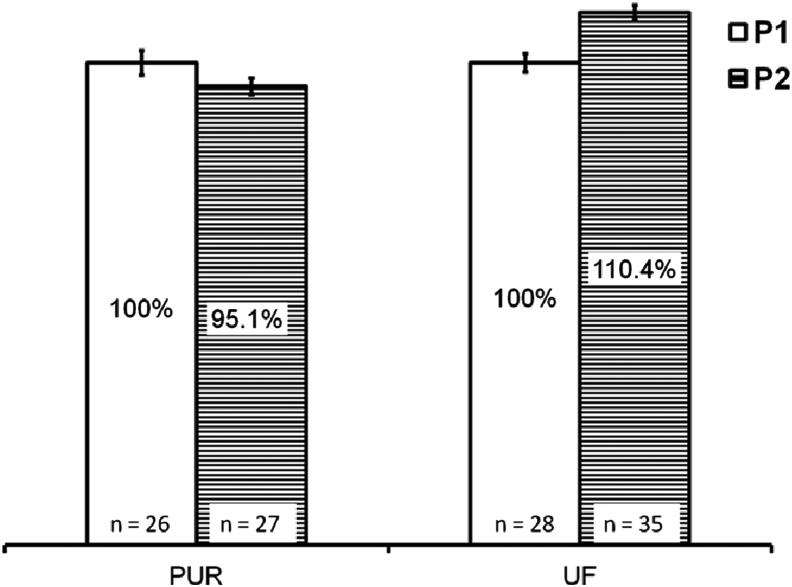

While the discussion of eventual differences in the adhesion between the cell wall and PUR or UF, respectively, has to rely only on the geometry of residual indents, the results presented in Figs. 3 and 6 allow to draw more straightforward and quantitative conclusions on differences in adhesion of these two adhesives to the cell wall surface types P1 and P2 examined in the present study. When UF is used for adhesive bonding, a higher peak force is required to achieve the target indentation displacement at P2, i.e. the freshly cut surface through the cell wall S2, compared to P1 located at the natural inner surface of the cell lumen (S3). Surprisingly, the opposite trend is found for the PUR-adhesive, where a higher force is required at P2 compared to P1. In accordance with the information from the mean F–d curves, the indentation energy obtained by numerical integration of the curves (Fig. 6) shows a highly significant increase (α<0.001) of approximately 10.4% for P2 indents on the UF-bonded sample as compared to P1-indents. For PUR-bonded samples, the variation is smaller but still significant with a 4.9% decrease of indentation work for the P1-indents compared to P2 (α<0.01). Considering Fig. 6 the difference in indentation work between P1 and P2 seems small at first view, but this impression is misleading. The indentation work shown in Fig. 6 is the sum of work spent for deforming the cell wall and the adhesive, and for separating the adhesive from the cell wall. For the indentation settings used in the present study, Obersriebing et al. [3] found that in a well bonded UF specimen the contribution of adhesion to the total indentation work is in the order of 15%. Therefore a difference of indentation work of+10.4% corresponds roughly to a change in adhesion in the order of+60%. The decrease in indentation work of 4.9% for the PUR bonded specimen would in that aspect indicate decreased adhesion strength of about 30%. However, it is at least doubtful if the contribution of work of adhesion to the total indentation work can be compared for these very different mechanical systems. Still, these remarkable values indicate significant differences in the chemistry of the cell wall surfaces at the two positions examined in the present study. It is well known that the hydrophilicity of a wood surface is highest when it is freshly cut, and decreases with increasing age of the surface [11]. With regard to the cell wall surfaces at P1 and P2 examined in the present study, results from chemical force microscopy support the assumption of different surface chemistry. The scan on the model system epoxy–lyocell, i.e. a less hydrophilic and a more hydrophilic surface, clearly shows better adhesion on the lyocell cross section for the AFM tip used in this experiment (Fig. 7a). Thus Fig. 7a indicates that the tip is sensitive to changes in surface polarity, showing higher adhesion to more polar surfaces. Several scans performed on the edge of cut open cells on the tangential section, containing the S2 and S3 layer of the cell wall, all showed better adhesion on the S2 layer (Fig. 7b and c), confirming its higher polarity as compared with the inner cell wall layer. This is even more notable as the sections were already a few days old, allowing the S2-layer time to age and lose some of its polarity. However, as can be seen in Fig. 7c, the variation between S2 and S3 is also clearly visible for the cut-open part of the S3-layer. This indicates different chemical properties not only at the (aged) surface but in the cell wall bulk. Thus one might assume that the cut-open surface present at P2 (Fig. 2) is more hydrophilic than the lumen surface at P1. On the other hand, liquid UF has a pronounced hydrophilic character due to its high content of water and abundance of accessible—OH groups [12] whereas the chemical structure of PUR [13] indicates much less pronounced hydrophilicity. Considering the different character of the two adhesives in terms of different degrees of hydrophilicity used in the present experiment, better adhesion of UF to P2 may be expected compared to P1, whereas the opposite is the case for PUR in agreement with the results presented in Fig. 6. Of course, it has to be mentioned that other properties, like the surface roughness or the indentation rate may influence the measured values of adhesive strength. However, it was found in a previous unpublished experiment that the roughness seems to have no significant influence on the outcome of this test compared to that of the surface polarity. The same is true for the indentation rate concerning the relative values of indentation energy, as long as the rate is kept below a threshold value. It is thus concluded that the observed differences in cell-wall surface chemistry are responsible for the differences in cell-wall adhesion measured with UF and PUR, respectively, in the present study.

Fig. 6.

Mean relative indentation work. The higher value is defined as 100%, the error bars represent the α=0.01 confidence intervals of the mean. n=number of indents performed for the sample type.

Fig. 7.

Selected AFM scan images. (a) Chemical force micrograph taken on a model lyocell–epoxy system, showing better adhesion (lighter colour) on the polar lyocell cross section. (b) Topography image at the edge of a cut open cell, showing the S2 and S3 layer of the cell wall. (c) Chemical force micrograph at the same position, showing better adhesion on the S2 layer, thus indicating its higher hydrophilicity; arrows indicate the cut-open part of the S3-layer in images b and c.

4. Conclusion

The results obtained in this study are of significance from two points of view. On the one hand, they demonstrate that the morphology of residual indents at the cell wall–adhesive interface delivers valuable qualitative information on the strength of adhesion. Clear indications were found that overall the interface between the wood call wall and PUR is weaker than the interface between the cell wall and UF. This can presumably be attributed to the penetration of UF into the cell wall. On the other hand, quantitative analysis of indentation curves at the interface demonstrated that the pattern of interaction between the cell wall and the adhesives PUR and UF differs fundamentally. While UF shows better adhesion to the more hydrophilic S2-layer of the cell wall and less adhesion to the natural inner cell wall surface (S3), PUR shows the opposite trend. The overall clarity of the results demonstrates the usefulness of this nanoindentation-based method for wood science and research on wood adhesion, e.g. evaluating the influence of different curing properties (temperature, humidity) on the final adhesive strength.

Acknowledgement

Funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF: Project No. P21681.

References

- 1.EN 302. Adhesives for load-bearing timber structures—Test methods; 2004.

- 2.Frihart C.R. Adhesive bonding and performance testing of bonded wood products. J ASTM Int. 2005;2 JAI12952. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obersriebnig M, Veigel S, Gindl-Altmutter W, Konnerth J. Direct evaluation of adhesive energy at the wood cell-wall urea-formaldehyde interface using nanoindentation technique. Holzforschung, in press.

- 4.Frihart C.R. Adhesive groups and how they relate to the durability of bonded wood. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2009;23:601–617. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaud F., Niemz P., Pizzi A. Structure-properties relationships in one component polyurethane adhesives for wood: sensitivity to low moisture content. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006:4181–4192. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konnerth J., Harper D., Lee S.H., Rials T.G., Gindl W. Adhesive penetration of wood cell walls investigated by scanning thermal microscopy (SThM) Holzforsch. 2008;62:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gindl W., Gupta H. Cell-wall hardness and Young's modulus of melamine-modified spruce wood by nano-indentation. Compos A. 2002;33:1141–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stöckel F., Konnerth J., Kantner W., Moser J., Gindl W. Tensile shear strength of UF- and MUF-bonded veneer related to data of adhesives and cell walls measured by nanoindentation. Holzforsch. 2010;64:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konnerth J., Jäger A., Eberhardsteiner J., Müller U., Gindl W. Elastic properties of adhesive polymers. II. Polymer films and bond lines by means of nanoindentation. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;102:1234–1239. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vick C.B., Okkonen E.A. Strength and durability of one-part polyurethane adhesive bonds to wood. For Prod J. 1998;48:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gindl M., Reiterer A., Sinn G., Stanzl-Tschegg S.E. Effects of surface ageing on wettability, surface chemistry, and adhesion of wood. Holz Roh Werkstoff. 2004;62:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheikl M., Dunky M. Measurement of dynamic and static contact angles on wood for the determination of its surface tension and the penetration of liquids into the wood surface. Holzforschung. 1998;52:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clauß S., Dijkstra D.J., Gabriel J., Kläusler O., Matner M., Meckel W. Influence of the chemical structure of PUR prepolymers on thermal stability. Int. J. Adhes Adhes. 2011;31:513–523. [Google Scholar]