Abstract

Vertebral cementoplasty is a well-known mini-invasive treatment to obtain pain relief in patients affected by vertebral porotic fractures, primary or secondary spine lesions and spine trauma through intrametameric cement injection. Two major categories of treatment are included within the term vertebral cementoplasty: the first is vertebroplasty in which a simple cement injection in the vertebral body is performed; the second is assisted technique in which a device is positioned inside the metamer before the cement injection to restore vertebral height and allow a better cement distribution, reducing the kyphotic deformity of the spine, trying to obtain an almost normal spine biomechanics. We will describe the most advanced techniques and indications of vertebral cementoplasty, having recently expanded the field of applications to not only patients with porotic fractures but also spine tumours and trauma.

INTRODUCTION

Vertebral cementoplasty is a well-established mini-invasive therapy in the treatment of patients affected by spine pain and vertebral compression fracture (VCF) due to porotic fractures, trauma and primary or secondary tumours; until the beginning of the 2000s, the majority of those treatments were mainly performed in patients affected by vertebral porotic fractures, but in the last 10 years, oncological applications have increased. The pathogenesis of spine pain in these patients is related to the stretching of periosteal nervous fibres caused by micromovements. The goal of intravertebral cement [poly-methyl-methacrylate (PMMA)] injection is the stabilization of those microfractures.

In literature, more than 1400 references are available under the voice “vertebroplasty” (VP); the majority of them include retrospective studies and case discussions; only few randomized control trials (RCT) are available. In 2009, two RCT compared VP with conservative approach in patients affected by osteoporotic vertebral fractures, showing many doubts about the real efficacy of VP;1,2 many criticisms about inclusion criteria, pre-treatment diagnostic evaluation, cross-over of patients and ethics were moved to those articles; however, in some countries, there was a clear reduction in the volume of VP performed after the publication of those trials. New RCT are going on to show the validity of those treatments (Vertos study) to validate evidence-based medicine.3–6 Recently, a meta-analysis conducted to compare surgical (including VP, AT VT, pedicle screw fixation, anterior and posterior reconstruction or fusion) vs non-surgical treatments for VCF with osteopenia concluded that surgical treatments were more effective in decreasing pain in the short, mid and long terms, but no differences in physical function and quality of life were observed in mid and long terms.7

Two major categories of treatment are included under the voice “vertebral cementoplasty”:

simple VP: cement injection is performed through a needle positioned within the vertebral body

ATs VT: a device of different sizes and shapes is first inserted into the metamer in order to restore the vertebral height, reach a better cement distribution and reduce the kyphotic deformity of the spine, and then, cement is injected.

VP was first performed in 1984 by Galimbert and Deramond for the treatment of a cervical haemangioma (C2), and only after few years, it found a clear application in the treatment of porotic vertebral fractures (fragility fractures).8,9 The first AT was balloon kyphoplasty, introduced in California, in 1998;10 since then, multiple percutaneous AT devices have been developed, and at moment, up to 21 systems are available worldwide in which vertebral height restoration is obtained through mechanical processes; only after the deployment of those systems, PMMA is injected through the cannula.10 In AT, a bilateral transpeduncolar approach is mandatory.11

In clinical practice, vertebral cementoplasty has major indications in selected patients affected by porotic VCF, trauma and primary and secondary spine tumours.12 In patients with porotic VCF suffering from insufficiency fractures located in the sacrum, upper thoracic and cervical levels, VP still remains the only treatment indication.12–14 AT is indicated in case of porotic or metastatic fractures at thoracolumbar levels with vertebral height reduction of at least 30–40%; the goal of this approach is the restoration of the vertebral height and the reduction of the kyphotic deformity.11,15

The aim of this paper was to describe the most advanced techniques and indications of vertebral cementoplasty.

Vertebral osteoporotic fractures

Osteoporosis is also called “the silent epidemy”, considering the increasing number of patients affected by this disease; a systemic medical approach is mandatory to reduce the effects of porotic VCF, such as respiratory and gastrointestinal dysfunctions. The main indication for vertebral cementoplasty is porotic VCF with spinal pain refractory to medical/physical treatment and orthesis devices.16–18 In a patient affected by a vertebral fracture, the risk to develop a new fracture in another metamer is 20% per year higher than in a patient without vertebral fractures;19 two-third of patients affected by porotic VCF will recover within 6–8 weeks, since the beginning of the clinical onset.

Principal indication to both VP or AT is the presence of a painful porotic VCF associated with an MR examination detecting hypointensity in T1 weighted sequences and hyperintensity in T2 short tau inversion recovery sequences corresponding to the suspicious level.6–12 This imaging-based approach is mandatory to plan the procedure and the number of vertebral bodies to treat; indeed, T2 weighted hyperintensity due to bone marrow oedema is a sign of not healed fracture.12,19 Reduction of the kyphotic deformity is the major target of AT, thanks to the capacity of the devices to restore the vertebral height. For this reason, AT should be recommended in case of loss of the vertebral height of at least 30–40% or more of the normal anatomical morphology.11 Recently, a cadaveric study20 demonstrated that sagittal height restoration was significantly better when using SpineJack® system (Vexim®, France) than balloon kyphoplasty; indeed, using the SpineJack device, the force needed to reduce the fracture can be directed in the craniocaudal direction, while in balloon kyphoplasty, individual anatomy and the balloon itself orientate the force direction.

In case of vertebra plana AT is not suggested because it is not technically feasible.11

Absolute contraindications are the presence of local or systemic infections, painless vertebral fractures and allergy to PMMA. Spinal cord or nerve root compressions associated with myelopathy and radiculopathy are instead urgent indications to surgery.19

The advantages of the AT are increased vertebral height capacity compared with VP, a low-pressure cement injection, use of high-density cement and low rate of vascular and disc leakage. Disadvantages of the AT vs VP are related to higher invasivity, higher costs and need for general anaesthesia in several cases; moreover, this procedure cannot be performed or at least there are no clear indications, in certain anatomical regions such as the sacrum, cervical–upper thoracic levels and in case of multilevel spine treatments.11 In these patients, no significant differences between VP and AT in terms of pain relief have been reported.

There are no significant differences in terms of new fracture incidence after surgical or conservative therapies, the occurrence of new vertebral fractures being due to ongoing osteoporosis and not to the type of fracture.7 Indeed, approximately 20% and 24% of patients undergoing VP after 1 year will present a new VCF, if initially they had one and more than one involved vertebra, respectively.18 This complication often occurs on the adjacent vertebra in approximately half of the cases, especially in the inferior endplate immediately superior to the treated level or the superior endplate of the vertebrae immediately inferior to the treated vertebra.21 For this reason, some authors proposed prophylactic VP22,23 by injecting bone cement into the adjacent part of the adjacent vertebral bodies, including the caudal part of the superior adjacent vertebral body and the cephalic part of the inferior adjacent vertebral body; this procedure should prevent the propagation of vertebral fractures by significantly lowering the incidence of adjacent fractures and reducing the necessity of multiple repeated VP procedures (Figure 1).22

Figure 1.

(a, b) A 71-year-old male affected by osteoporotic fracture of the L1; latero-lateral (a) and anteroposterior (b) fluoroscopy controls after vertebroplasty (VP) of the L1 associated with prophylactic VP of the T12 and L2.

Spine malignancies

The spine can be affected by primary or secondary tumours, with progressive bone abnormality involving one or more portions of the vertebra (posterior arch, pedicles and body); this leads to unsustainable local pain and motor impairment secondary to vertebral collapse and potential nervous structure compression.24,25 In the last decade, the prolongation of life expectancy in patients with oncological disease has led to an increase in vertebral metastasis detection, especially in case of breast, lung, renal, prostate and haematopoietic cancers; approximately 70% of patients with secondary lesions have at least one vertebral metastasis.26 At least 20% of patients affected by neoplastic disease present spinal metastasis symptoms as initial presentation.27

Management of spinal tumours includes different therapy options such as medical therapy (corticosteroids and chemotherapy), radiotherapy, surgical treatment, VP and radiofrequency (RF) ablation; this depends on histology, tumour size, location, age of patient, and clinical data. Surgery is recommended in case of spinal cord compression (laminectomy, corpectomy and en bloc resection), spinal instability and severe pain.28,29 Despite chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy present a good outcome in terms of mass reduction/resolution with pain relief effect up to 71% of patients,30 their action requires long time while the immediate risk of vertebral fracture remains.31,32

In vertebral tumour management, it is crucial to recognize vertebral instability due to tumour infiltration. As defined by the Spine Oncologic Study Group, this condition consists of loss of spinal integrity associated with pain related to movement, symptomatic deformity and progressive neurological deficit under physiological load.31,32 The risk of sudden collapse of a vertebra depends on the level involved: in the thoracic district, it is elevated if the tumour involves >60% of the vertebral body or in case of 30% body destruction associated with costovertebral joint involvement;31 in the lumbar district, it is elevated if the lesion involves 35–40% of the vertebral body or in case there is only 20–25% of body destruction but associated with posterior arch and/or pedicle involvement.31,32

The Spine Oncologic Study Group has divided patients affected by spine neoplasms into three groups: stable, possible unstable and unstable. VP has been validated as an excellent procedure in the stable and possible unstable groups,33 producing a rapid pain relief effect in 84–92% of patients and asymptomatic paravertebral cement leakage accounting for only 4–9.2% of patients.34–37 In this context, VP has two aims: (a) mechanical stabilization of the vertebra, in order to prevent deformation of the vertebral body and complications related to neural compression; (b) pain resolution related to the disease (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a–e) A 65-year-old male affected by multiple myeloma suffering from back pain, resistant to medical therapy. Multiple vertebral compression fractures on sagittal T1 weighted and T2 weighted MRI (a–b), some of them with sclerotic responses as shown on sagittal multiplanar-reformatted multidetector CT (c). Latero-lateral and anteroposterior fluoroscopy controls after vertebroplasty performed at the thoracolumbar junction.

Neoplastic vertebral erosion, epidural and/or posterior wall involvement are not contraindications to VP anymore. Performing VP using high-viscosity and dense cement, with long working time and slow injection rate under continuous fluoroscopy control leads to a severe reduction of venous or spinal canal leakages.38–40 In addition, new devices applied during cement injection, such as RF, allow both antineoplastic action and bone remodelling to be performed while cement remains in the vertebral body or in the tumour lesion, with low risk of leakage (Figures 3 and 4).41

Figure 3.

(a–i) A 68-year-old female affected by multiple myeloma suffering from back pain, resistant to medical therapy. A vertebral compression fracture at the T11 with soft epidural tissue infiltration on sagittal T2 weighted, short tau inversion recovery and T1 weighted MRI (a–c). Latero-lateral (LL) and anteroposterior (AP) fluoroscopy controls during vertebroplasty (VP) of the T11 (d–e) by bipeduncolar approach. LL fluoroscopy control after radiofrequency (RF) ablation needle placement into the T11 (f). AP and LL fluoroscopy controls after VP using an RF ablation system (g–h). Post-VP multiplanar-reformatted multidetector CT control showed good distribution of the cement into the vertebral body without leakages (i).

Figure 4.

(a–c) A 65-year-old female affected by breast cancer with lytic metastasis involving the left pedicle and posterior arch of the T8 (a). Latero-lateral and anteroposterior fluoroscopy controls after vertebroplasty performed using radiofrequency system injection show a paravertebral venous leakage (b–c).

Another recent VP indication is the possibility to perform VP in case of vertebral lesions associated with extravertebral soft-tissue mass. Previous literature considered extravertebral tumour mass as a contraindication, especially in case of severe epidural extension. Today, severe compressive myelopathy remains an indication for conventional open surgery for spinal cord decompression, but VP can be performed even in case of epidural involvement with palliative target, thanks to high-viscosity cement with low risk of emboligenous dissemination.42 The pedicle and the posterior arch are fundamental for spine stability: if the pedicle/posterior arch is involved by the tumour, 25% body erosion is enough to cause vertebral instability.31,32 To prevent fractures and to stabilize the spinal segment, a double-fluoro-CT-guided VP can be performed using small-gauge needles (13–15 G) and multiple PMMA mini-injections in order to restore every part of the posterior arch, sparing the spinal canal.

Apart from the traditional transpedicular approach, new access routes to reach the vertebral body have been adopted by several authors, like the parapedicular or transdiscal access; in these cases, the main advantage of performing procedures guided by both fluoroscopy and CT is the possibility to choose the best route to reach the target, as no skeletal markers (i.e. pedicles) are needed.43

RF ablation, before performing VP, represents a new approach for the treatment of spinal tumour. This technique has already been extensively applied for the treatment of lung, kidney and prostate cancers; it consists in a probe placed into the lesion by a transpedicular approach that releases thermal energy and consequently necrotizes the tumour, creating a cavity for cement injection. Furthermore, it induces thrombosis of the paravertebral and intravertebral venous plexus, minimizing procedure-related complications.44,45 In the spine, this treatment has traditionally been limited to lesions within the anterior vertebral body because of the location, sufficiently distant from sensitive neural elements, and because of the reduced needle excursion angle deriving from the transpedicular or extrapedicular approach of conventional RF ablation systems.46 Recently, new articulated ablation needles have been developed in order to provide easy access to posterior vertebral body lesions and to modify the direction of the probe inside the lesion without removing the needle; because of the proximity with neural tissues, some devices present also two built-in thermocouples to monitor safely and in real time the peripheral edge of the ablation zones.47 Furthermore, curved steerable needles are applied also to target cement injections into regions technically challenging to access with straight needles, like sacrum and extravertebral locations as posterior acetabulum.48

The last percutaneous ablation technique introduced for spine metastasis is cryoablation; the cytotoxic effects of this technique are mediated by the formation of intracellular ice crystals during probe-mediated temperature manipulation, inducing the creation of an enlarging ice ball. New evidences showed that percutaneous cryoablation is safe and effective for both vertebral local tumour control and palliation of painful spine metastases in patients refractory to radiation therapies and chemotherapic palliatives therapies.49 In contrast to RF ablation, cryoablation results in formation of a hypoattenuating ice-ball, which is readily identified by CT, beyond which tissues are safe from thermal injury.50 Additionally, cryoablation is effective in the treatment of osteoblastic metastases where high impedance often renders RF ablation ineffective.49 However, nerve roots are more vulnerable to potential thermal injury with cryoablation compared with RF ablation and so thermoprotection techniques need to be taken into account while using this approach.

Neoplastic involvement of the sacrum can be part of secondary diseases, being responsible for severe local pain, preventing the patient to sit or stand-up position. Metastases are frequently observed in the sacrum because of the improved survival rate of many neoplasms characterized by lytic metastases; furthermore external radiation, oriented directely to the sacrum or scattered from pelvic radiations, and osteoporosis, paraneoplastic or related to chemotherapy, are responsible of sacral fractures.51 In this field, sacroplasty using intratumoral injection of cement revealed a powerful tool in pain relief, even in case of very small sacral lesions Figure 5. The risk of performing sacroplasty is related to foraminal leakage especially injecting standard PMMA,52 therefore all lesions should be evaluated carefully with MRI and CT before the procedure. During sacroplasty procedures, a combined fluoro- and CT-guidance associated with manual PMMA micro-injections with small syringes (i.e. 1.5–2 cm3) are the best options to reduce the leakage risk;53,54 in this way, potential intraforaminal extravasations are appreciable in the initial phases of the injection, in order to promptly stop the procedure and remove the needle. Furthermore the best needle entry points and orientations can be easily chosen: according to the shape of the sacrum and the distribution of sacral osteolysis, the needle should be positioned in order to cover the whole extension of the sacral fracture; usually, given their ease relative to long-axis approaches, multiple short-axis trajectories perpendicular to the sacral ala are preferred to maximize treatment volumes, at the expense of multiple needle placements.51

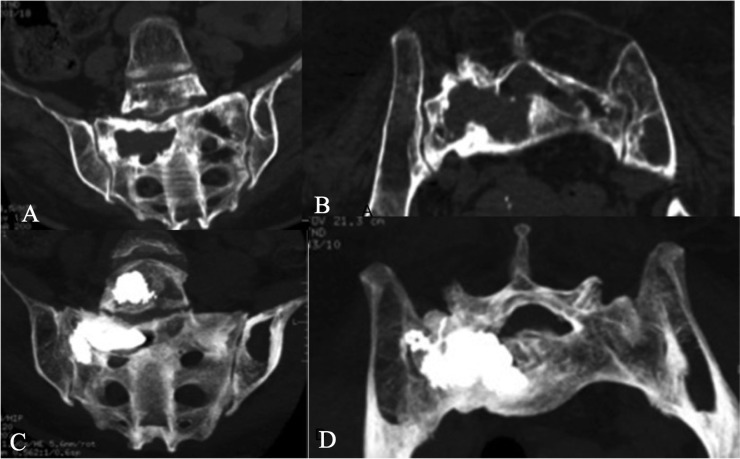

Figure 5.

(a–d) A large non-Hodgkin lymphoma destroying the right hemivertebra of the L5 and right sacral wing (a–b). Thanks to a CT-guided sacroplasty, poly-methyl-methacrylate injection completely refilled the osteolytic areas, avoiding intraforaminal leakages at the sacrum level.

Aneurysmal bone cysts

The aneurismal bone cyst (ABC) is a pseudotumoral hyperaemic/haemorrhagic, expansive osteolytic lesion with a thin wall, containing blood-filled cystic cavities. Although benign, the ABC can be locally aggressive and can cause extensive weakening of the bony structure and impingement on surrounding tissues; malignant transformation is extremely rare.55 It tends to affect patients younger than 20 years, with female preponderance. The true aetiology is still unknown. About 14% of all ABCs are encountered in the spine, with those in the cervical spine being only 2%.56 Usually, it produces a pain syndrome, resistant to continuous medical medications.55

Treatment of spinal ABC is controversial. For vertebral lesions, the operators must consider the risk of neurologic and vascular lesions, preserving spine stability and, if possible, spine mobility.55–57 Surgery is still considered to be the treatment of choice including resection, curettage and spine fixation. These procedures entail the post-operative risks of spinal deformity and haemorrhage owing to their high vascularity.58 Percutaneous intralesional direct embolization with different agents (glue, Onyx, alchool, Ethilbloc) represents a relatively new mini-invasive therapeutic option for the treatment of ABCs, sometimes combined with surgery or endovascular treatments, especially for large and resistant lesions.59

In these lesions, VP aims to combine pain relief with spine stability, filling the lesion with cement.60 Until today, the bone cement most commonly used was the above-mentioned PMMA; the success of this material is based on immediate pain relief and mechanical stabilization improving physical functions, as well as low cost. However, clinical trial results have highlighted55,61,62 potential weaknesses such as thermal injury to surrounding tissues with neurological damages, increasing fracture risk in adjacent levels owing to the high inherent stiffness and potential toxicity caused by the reactive elements.63–67 New injectable materials such as calcium phosphate, bioactive glass and calcium sulphate cement are being developed, and they seem suitable for vertebral stabilization and augmentation in young patients,65–67 as the patients affected by ABC. However, some authors reported that these osteoconductive cements, even when presenting immediate and long-term effectiveness with long-lasting pain relief and improved quality of life, entail some disadvantages compared with standard PMMA cements: higher costs, higher rates of disc and venous leakages and new incidental adjacent fractures.66–70

To bypass these drawbacks, a new kind of bioactive osteoconductive material (CeramentTM; Bonesupport®, Sweden) has been proposed in the attempt to obtain bone regrowth in the focal osteolytic area64,71 (Figure 6). It is composed of resorbable calcium sulfate and hydroxyapatite with osteoconductive properties; the hydroxyapatite acts as a slow or non-absorbable framework which slows down the absorption rate of calcium sulfate and, at the same time, acts as an osteoconductive template for new bone ingrowths.72 The action of the new bone substitute Cerament lies in specific biomechanical and biological properties to support the spinal column associated with antalgic effect. Using PMMA cement, the patient has no osteointegration of the injected material; instead, this new generation of cement will be resorbed at a rate equal to new bone ingrowth, achieving complete bone remodelling and healing.71

Figure 6.

(a–r) A 30-year-old male affected by symptomatic aneurysmal bone cyst resistant to medical therapy involving the body and posterior elements of the L3 (a–d). Under fluoroscopy control, with the patient standing prone and under neuroleptoanalgesia, a bioactive cement (Cerament™; Bonesupport®, Sweden) was injected into the L3 by a monopeduncolar approach filling the lesion without cement leakages (e–h). The post-treatment multidetector CT (MDCT) with multiplanar-reformatted (MPR) and three-dimensional volume rendering reconstructions confirmed the cement distribution into the lesion without cement leakages (i–n). The 6-month MDCT with MPR reconstruction follow-up showed the sclerotic bone remodelling of the aneurysmal cyst with periosteal new bone formation, followed by recalcification within the cystic cavity (o–r).

Vertebral haemangiomas

Vertebral haemangiomas (VH) are benign tumours with a rich vasculature; they are relatively common, representing 2–3% of all spinal tumours. Usually, these are asymptomatic and are diagnosed as accessory findings during X-ray or MRI examinations performed for other purposes. If symptomatic, they can present from simple vertebral pain (54% of cases)—sometimes resistant to conservative medical treatment—to progressive neurological deficits.73

Management of VH remains complex. Surgery and radiotherapy are still considered treatments of choice, but intraoperative and post-operative haemorrhagic complications related to the rich vascularization typical of these lesions must be taken into account; therefore, these procedures are often preceded by a pre-operative embolization in the acute setting.74,75

Symptomatic VH, with or without aggressive signs on MR (marked enhancement, epidural tissue, hypointensity on T1 weighted with hyperintensity on T2 weighted or short tau inversion recovery sequences and cortical erosions), is a strong indication to VP, with an antalgic effect ranging from 90% to 100% of cases. The basic principle of this approach is to overfill completely the vertebral lesion with cement (PMMA) in order to determine an irreversible de-afferentation and sclerosis of the haemangiomatous venous pool; in these cases, a bipedicular approach is recommended.14

Vertebral traumatic fractures

Vertebral traumatic fractures can be stable or unstable, in relation to the three- or four-column theory (Denis and Calzolari).76,77 The most applied classification for surgical or non-surgical treatment in case of vertebral fracture is the Magerl classification that divides the trauma into compression, rotation and distraction, with multiple subtypes.

Vertebral cementoplasty with VP or AT, depending on the degree of vertebral height loss, has a major indication in patients with Magerl A1-type fractures.11 These subjects can also be treated with orthesis devices, bed rest and medical/physical therapy for at least for 3–6 months; however, these treatments cannot exclude the possibility of worsening with an increase of kyphotic deformity and consequent problems related to orthesis, such as cardiorespiratory impairment, sleep problems and gastrointestinal motility reduction. AT can restore vertebral height, obtaining better homogeneous distribution of the cement with better axial resistance to load (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7.

(a–f) A 35-year-old male affected by a traumatic A1 Margerl vertebral compression fracture of the T11. Under fluoroscopy control, with the patient standing prone and under neuroleptoanalgesia, a bioactive cement (Cerament™; Bonesupport®, Sweden) was injected into the T11 by bipeduncolar approach without cement leakages (a–c). The 4-month multidetector CT follow-up with multiplanar-reformatted reconstructions showed the sclerotic bone reaction of the fracture (d–f).

Figure 8.

(a–g) A 42-year-old female affected by a traumatic vertebral compression fracture of the T12 with kyphosis deformity on sagittal multiplanar-reformatted multidetector CT reconstruction (a). Under fluoroscopy control, with the patient standing prone and under neuroleptoanalgesia, the SpineJack® device (Vexim®, France) was placed into the T12 by a bipeduncolar approach (c–e) without cement leakages. The anteroposterior and latero-lateral fluoroscopy controls after cement injection show no leakages (f–g).

In selected cases, vertebral cementoplasty can be considered also in patients with Magerl A2 and A3 fractures, such as patients with polytrauma with comorbidities (patients with long bone fractures, abdominal trauma etc.), elderly patients in whom surgical indication is not suggested and patients in whom surgical and anaesthesiologist risk is too high.11 There are no absolute rules about the age threshold regarding AT, however, in young patients the treatment should be performed as soon as possible; indeed, it must be considered that the bone metabolism in a young patient is much faster than in an old one.11

CONCLUSION

Vertebral cementoplasty is a safe and effective technique for the treatment of a wide spectrum of spine pathologies, including osteoporotic and traumatic fractures, primary and secondary tumours. In the last decade, significant improvements have occurred in the field of oncological spine interventions, combining tumour ablation procedures with cementoplasty. The choice between VP or AT depends on operator experience, spine pathology and correct selection criteria. The diffusion of high-viscosity cements with long working time and the introduction of osteoconductive materials have widened the number of treatable patients. Performing those procedures in high-quality angio suite, combining C-arm and CT guidance, would reduce complication rate and allow treatment of lesions in unfavourable locations.

Contributor Information

Mario Muto, Email: mutomar@tiscali.it.

Gianluigi Guarnieri, Email: gianluigiguarnieri@hotmail.it.

Francesco Giurazza, Email: francescogiurazza@hotmail.it.

Luigi Manfrè, Email: lmanfre@me.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, Turner JA, Wilson DJ, Diamond TH, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 569–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, Wark JD, Mitchell P, Wriedt C, et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 557–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voormolen MH, Mali WP, Lohle PN, Fransen H, Lampmann LE, van der Graaf Y, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty compared with optimal pain medication treatment: short-term clinical outcome of patients with subacute or chronic painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. The VERTOS study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 555–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, Jansen FH, Tielbeek AV, Blonk MC, et al. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 1085–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60954-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klazen CA, Venmans A, de Vries J, van Rooij WJ, Jansen FH, Blonk MC, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty is not a risk factor for new osteoporotic compression fractures: results from VERTOS II. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 1447–50. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venmans A, Lohle PN, van Rooij WJ. Pain course in conservatively treated patients with back pain and a VCF on the spine radiograph (VERTOS III). Skeletal Radiol 2014; 43: 13–18. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1729-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo JB, Zhu Y, Chen BL, Xie B, Zhang WY, Yang YJ, et al. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for vertebra compression fracture with osteopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0127145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, Le Gars D. Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty. Neurochirurgie 1987; 33: 166–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lapras C, Mottolese C, Deruty R, Lapras C, Jr, Rmond J, Duquesnel J. Percutaneous injection of methyl-metacrylate in osteoporosis and severe vertebral osteolysis (Galibert’s technics). [In French.] Ann Chir 1989; 43: 371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garfin SR, Yuan HA, Reiley MA. New technologies in spine: kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001; 26: 1511–5. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muto M, Marcia S, Guarnieri G, Pereira V. Assisted techniques for vertebral cementoplasty: why should we do it? Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 783–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muto M, Perrotta V, Guarnieri G, Lavanga A, Vassallo P, Reginelli R, et al. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty: friends or foes? Radiol Med 2008; 113: 1171–84. doi: 10.1007/s11547-008-0301-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarnieri G, Vassallo P, Ambrosanio G, Zecolini F, Lavanga A, Varelli C, et al. Vertebroplasty as a treatment for primary benign or metastatic cervical spine lesions: up to one year of follow-up. Neuroradiol J 2010; 23: 90–4. doi: 10.1177/197140091002300115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarnieri G, Ambrosanio G, Vassallo P, Pezzullo MG, Galasso R, Vertebroplasty as treatment of aggressive and symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas: up to 4 years of follow-up. Neuroradiology. 2009; 51: 471–6. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0520-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muto M, Greco B, Setola F, Vassallo P, Ambrosanio G, Guarnieri G. Vertebral body stenting system for the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: follow-up at 12 months in 20 cases. Neuroradiol J 2011; 24: 610–9. doi: 10.1177/197140091102400418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deramond H, Depriester C, Galibert P, Le Gars D. Percutaneous vertebroplasty with polymethylmethacrylate. Technique, indications, and results. Radiol Clin North Am 1998; 36: 533–46. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gangi A, Guth S, Imbert JP, Marin H, Dietermann JL. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: indications, technique, and results. Radiographics 2003; 23: 10–20. doi: 10.1148/rg.e10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C, Hanley DA, Barton I, Broy SB, et al. Risk of new vertebral fractures in the year following a fracture. JAMA 2001; 285: 320–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathis JM, Barr JD, Belkoff SM, Barr MS, Jensen ME, Deramond H. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: a developing standard of care for vertebral compression fractures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 373–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kruger A, Oberkircher L, Figiel J, Flodorf F, Bolzinger F, Noriega DC, et al. Height restoration of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures using different intravertebral reduction devices: a cadaveric study. Spine J 2015; 15: 1092–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trout AT, Kallmes DF. Does vertebroplasty cause incident vertebral fractures? A review of available data. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 1397–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yen CH, Teng MMH, Yuan WH, Sun YC, Chang CY. Preventive vertebroplasty for adjacent vertebral bodies: a good solution to reduce adjacent vertebral fracture after percutaneous vertebroplasty. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 826–32. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diel P, Freiburghaus L, Roder C, Benneker LM, Popp A, Perler G, et al. Safety, effectiveness and predictors for early reoperation in therapeutic and prophylactic vertebroplasty: short-term results of a prospective case series of patients with osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Eur Spine J 2012; 21(Suppl. 6): S792–9. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1989-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chi JH, Bydon A, Hsieh P, Witham T, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL. Epidemiology and demographics for primary vertebral tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2008; 19: 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Shyangdan D, Court R, Kandala NB, Clarke A. A systematic review of evidence on malignant spinal metastases: natural history and technologies for identifying patients at high risk of vertebral fracture and spinal cord compression. Health Technol Assess 2013; 17: 1–274. doi: 10.3310/hta17420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eleraky M, Papanastassiou I, Vrionis FD. Management of metastatic spine disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2010; 4: 182–8. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32833d2fdd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rougraff BT, Kneisl JS, Simon MA. Skeletal metastases of unknown origin: a prospective study of a diagnostic strategy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993; 75: 1276–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinstein JN. Surgical approach to spine tumor. Orthopedics 1989; 12: 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart RA, Boriani S, Biagini R, Currier B, Weinstein JN. A system for surgical staging and management of spine tumors. A clinical outcome study of giant cell tumors of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997; 22: 1773–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sørensen S, Helweg-Larsen S, Mouridsen H, Hansen HH. Effect of high-dose dexamethasone in carcinomatous metastatic spinal cord compression treated with radiotherapy: a randomised trial. Eur J Cancer 1994; 30A: 22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taneichi H, Kaneda K, Takeda N, Abumi K, Satoh S. Risk factors and probability of vertebral body collapse in metastases of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997; 22: 239–45. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702010-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC, Bilsky MH, Shaffrey CI, Berven SH, et al. A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: an evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35: E1221–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e16ae2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barr JD, Jensen ME, Hirsch JA, McGraw JK, Barr RM, Brook AL, et al. Position statement on percutaneous vertebral augmentation: a consensus statement developed by the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), American College of Radiology (ACR), American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR), American Society of Spine Radiology (ASSR), Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (CIRA), and the Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS). J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25: 171–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berenson J, Pflugmacher R, Jarzem P, Zonder J, Schechtman K, Tillman JB, et al. Balloon kyphoplasty versus non-surgical fracture management for treatment of painful vertebral body compression fractures in patients with cancer: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 225–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calmels V, Vallée JN, Rose M, Chiras J. Osteoblastic and mixed spinal metastases: evaluation of the analgesic efficacy of percutaneous vertebroplasty. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 570–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheung G, Chow E, Holden L, Vidmar M, Danjoux C, Yee AJ, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with intractable pain from osteoporotic or metastatic fractures: a prospective study using quality-of-life assessment. Can Assoc Radiol J 2006; 57: 13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fourney DR, Schomer DF, Nader R, Chlan-Fourney J, Suki D, Ahrar K, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for painful vertebral body fractures in cancer patients. J Neurosurg 2003; 98(1 Suppl.): 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaefer O, Lohrmann C, Markmiller M, Uhrmeister P, Langer M. Combined treatment of a spinal metastasis with radiofrequency heat ablation and vertebrioplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180: 1075–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Linden E, Kroft LJ, Dijkstra PD. Treatment of vertebral tumor with posterior wall defect using image-guided radiofrequency ablation combined with vertebroplasty: preliminary results in 12 patients. J Vasc Int Radiol 2007; 18: 741–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gstöttner M, Angerer A, Rosiek R, Bach CM. Quantitative volumetry of cement leakage in viscosity-controlled vertebroplasty. J Spinal Disord Tech 2012; 25: E150–4. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31823f62b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trumm CG, Jakobs TF, Stahl R, Sandner TA, Paprottka PM, Reiser MF, et al. CT fluoroscopy-guided vertebral augmentation with a radiofrequency-induced, high-viscosity bone cement (StabiliT(®)): technical results and polymethylmethacrylate leakages in 25 patients. Skeletal Radiol 2013; 42: 113–20. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1386-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saliou G, Kocheida al M, Lehmann P, Depriester C, Paradot G, Deramond H, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for pain management in malignant fracture of the spine with epidural involvement. Radiology 2010; 254: 882–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09081698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andreson DE, Cotton JR. Mechanical analysys of percutaneous sacroplasty using CT imaged based finite element model. Med Eng Phys 2007; 29: 316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakatsuka A, Yamakado K, Takaki H, Uraki J, Makita M, Oshima F, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of painful spinal tumors adjacent to the spinal cord with real-time monitoring of spinal canal temperature: a prospective study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009; 32: 70–5. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9390-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schaefer O, Lohrmann C, Markmiller M, Uhrmeister P, Langer M. Technical innovation. Combined treatment of a spinal metastasis with radiofrequency heat ablation and vertebroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180: 1075–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.4.1801075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thanos L, Mylona S, Galani P, Tzavoulis D, Kalioras V, Tantales S, et al. Radiofrquency ablation of osseous metastases for the palliation of pain. Skeletal Radiol 2008; 37: 189–94. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0404-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anchala PR, Irving WD, Hillen TJ, Friedman MV, Georgy BA, Coldwell DM, et al. Treatment of metastatic spinal lesions with a navigational bipolar radiofrequency ablation device: a multicenter retrospective study. Pain Physician 2014; 17: 317–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy DT, Korzan JR, Ouellette HA, Liu DM, Clarkson PW, Munk PL. Driven around the bend: novel use of a curved steerable needle. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2013; 36: 531–5. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0482-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomasian A, Wallace A, Northrup B, Hillen TJ, Jennings JW. Spine cryoablation: pain palliation and local tumor control for vertebral metastases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol Oct 2015. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saliken JC, McKinnon JG, Gray R. CT for monitoring cryotherapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 166: 853–55. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.4.8610562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moussazadeh N, Laufer I, Werner T, Krol G, Boland P, Bilsky MH, et al. Sacroplasty for cancer-associated insufficiency fractures. Neurosurgery 2015; 76: 446–50. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pommershei W, Huang-Hellinger F, Baker M, Morris P. Sacroplasty: a treatment for sacral insufficiency fractures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24: 1003–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia JM, Doblaré M, Seral B, Seral F, Palanca D, Gracia L. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of several internal and external pelvis fixations. J Biomech Eng 2000; 122: 516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson DE, Cotton JR. Mechanical analysys of percutaneous sacroplasty using CT imaged based finite element model. Med Eng Phys 2007; 29: 316–25. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boriani S, De Lure F, Campanacci L, Gasbarrini A, Bandiera S, Biagini R, et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the mobile spine. Eur Spine J 2001; 26: 27–35. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tokarz F, Jankowski R, Zukiel R, Nowak S. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the skull and vertebral column treated operatively [In Polish.] Neurol Neurochir Pol 1993; 27: 533–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schreuder HW, Veth RP, Pruszczynski M, Lemmens JA, Koops HS, Molenaar WM. Aneurysmal bone cysts treated by curettage, cryotherapy and bone grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985; 67-B: 310–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boriani S, Lo SF, Puvanesarajah V, Fisher CG, Varga PP, Rhines LD, et al. ; AOSpine Knowledge Forum Tumor. Aneurysmal bone cysts of the spine: treatment options and considerations. J Neurooncol 2014; 120: 171–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1540-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guarnieri G, Ambrosanio G, Vassallo P, Muto M. Combined percutaneous and endovascular treatment of symptomatic aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine: clinical six months. Follow-up of six cases. Neuroradiol J 2010; 23: 74–84. doi: 10.1177/197140091002300113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fahed R, Clarençon F, Riouallon G, Cormier E, Bonaccorsi R, Pascal-Mousselard H, et al. Just a drop of cement: a case of cervical spine bone aneurysmal cyst successfully treated by percutaneous injection of a small amount of polymethyl-methacrylate cement. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: e4. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011541.rep [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinson Y, Heyde CE, Försth P, Olerud C. Kyphoplasty in osteoportic vertebral compression fractures-guidelines and technical considerations. J Orthop Surg Res 2011; 6: 43. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-6-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Nakshabandi NA. Percutaneous vertebroplasty complications. Ann Saudi Med 2011; 31: 294–7. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.81542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rauschmann M, Vogl T, Verheyden A, Pflugmacher R, Werba T, Schmidt S, et al. Bioceramic vertebral augmentation with a calcium sulphate/hydroxyapatite composite (Cerament SpineSupport): in vertebral compression fractures due to osteoporosis. Eur Spine J 2010; 19: 887–92. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1279-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcia S, Boi C, Dragani M, Marini S, Marras M, Piras E, et al. Effectiveness of a bone substitute (CERAMENT™) as an alternative to PMMA in percutaneous vertebroplasty: 1-year follow-up on clinical outcome. Eur Spine J 2012; 21(Suppl. 1): S112–8. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2228-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu XS, Zhang ZM, Mao HQ, Geng DC, Zou J, Wang GL, et al. A novel sheep vertebral bone defect model for injectable bioactive vertebral augmentation materials. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2011; 22: 159–64. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4191-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lim TH, Brebach GT, Renner SM, Kim WJ, Kim JG, Lee RE, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of an injectable calcium phosphate cement for vertebroplasty. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002; 27: 1297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grafe IA, Baier M, Noldge G, Weiss C, Da Fonseca K, Hillmeier J, et al. Calcium–phosphate and polymethylmethacrylate cement in long-term outcome after kyphoplasty of painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008; 33: 1284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maestretti G, Cremer C, Otten P, Jakob RP. Prospective study of standalone balloon kyphoplasty with calcium phosphate cement augmentation in traumatic fractures. Eur Spine J 2007; 16: 601–10. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0258-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burguera EF, Xu HH, Sun L. Injectable calcium phosphate cement: effects of powder-to-liquid ratio and needle size. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2008; 84: 493–502. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guarnieri G, Tecame M, Izzo R, Vassallo P, Sardaro A, Iasiello F, et al. Vertebroplasty using calcium trygliceride bone cement (Kryptonite) for vertebral compression fractures: a single-centre preliminary study of outcomes at one-year follow-up. Interv Neuroradiol 2014; 20: 576–82. doi: 10.15274/INR-2014-10060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guarnieri G, Vassallo P, Muto M, Muto M. Percutaneous treatment of symptomatic aneurysmal bone cyst of L5 by percutaneous injection of osteoconductive material (Cerament). J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: e43. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010912.rep [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Masala S, Nano G, Marcia S, Muto M, Fucci FP, Simonetti G. Osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture augmentation by injectable partly resorbable ceramic bone substitute (Cerament™ SPINESUPPORT): a prospective nonrandomized study. Neuradiology 2012; 54; 1245–51. doi: 10.1007/s00234-012-1016-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gaudino S, Martucci M, Colantonio R, Lozupone E, Visconti E, Leone A, et al. A systematic approach to vertebral hemangioma. Skeletal Radiol 2015; 44: 25–36. doi: 10.1007/s00256-014-2035-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heyd R, Seegenschmiedt MH, Rades D, Winkler C, Eich HT, Bruns F, et al. German Cooperative Group on radiotherapy for benign diseases. Radiotherapy for symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas: results of a multicenter study and literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 77: 217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sedora-Roman NI, Gross BA, Reddy AS, Ogilvy CS, Thomas AJ. Intra-arterial onyx embolization of vertebral body lesions. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 2013; 15: 320–5. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2013.15.4.320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Panjabi MM, Oxland TR, Kifune M, Arand M, Wen L, Chen A. Validity of the three-column theory of thoracolumbar fractures. A biomechanic investigation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995; 20: 1122–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Denis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983; 8: 817–31. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198311000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]