Abstract

Objective:

To use a Likert scale method to optimize image quality (IQ) for cone beam CT (CBCT) soft-tissue matching for image-guided radiotherapy of the prostate.

Methods:

23 males with local/locally advanced prostate cancer had the CBCT IQ assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (4 = excellent, no artefacts; 3 = good, few artefacts; 2 = poor, just able to match; 1 = unsatisfactory, not able to match) at three levels of exposure. The lateral separations of the subjects were also measured. The Friedman test and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to determine if the IQ was associated with the exposure level. We used the point-biserial correlation and a χ2 test to investigate the relationship between the separation and IQ.

Results:

The Friedman test showed that the IQ was related to exposure (p = 2 × 10−7) and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test demonstrated that the IQ decreased as exposure decreased (all p-values <0.005). We did not find a correlation between the IQ and the separation (correlation coefficient 0.045), but for separations <35 cm, it was possible to use the lowest exposure parameters studied.

Conclusion:

We can reduce exposure factors to 80% of those supplied with the system without hindering the matching process for all patients. For patients with lateral separations <35 cm, the exposure factors can be reduced further to 64% of the original values.

Advances in knowledge:

Likert scales are a useful tool for measuring IQ in the optimization of CBCT IQ for soft-tissue matching in radiotherapy image guidance applications.

INTRODUCTION

Image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT) using cone beam CT (CBCT) is an increasingly common practice. With all uses of ionizing radiation, the radiation dose should be optimized. In CBCT, optimization requires the imaging dose to be reduced while keeping the image quality (IQ) suitable for the task in hand (in this case matching the CBCT with the planning CT to ensure the prostate is within the target volume delineated on the planning CT).1 IQ is a multiparametric quantity. According to Månsson,2 it can be described in multiple ways: purely physical terms; psychophysical terms; using observer performance; or diagnostic performance. An increasingly accepted operational definition of IQ is to measure the relationship with the intended task of the image.1,3 Here, we have used a Likert scale method to quantify subjective IQ for the task of soft-tissue matching. Likert scales are probably the most common type of rating scale used in human-subject research. They have been widely employed in investigating IQ in diagnostic radiology.4–6 We wished to optimize the IQ of our CBCT system for the process of soft-tissue matching in the case of prostate radiotherapy. Preliminary data with an anthropomorphic phantom (Virtually Human Male Pelvis Phantom Model 801-P; CRIS Inc. Norfolk, VA) had indicated that we could reduce the exposure parameters by approximately one-third without an unacceptable reduction in IQ. However, owing to the natural variation in patient size, shape and anatomy, we needed to validate this result in the clinical environment. To do this, we set up a service improvement study to optimize CBCT dose for prostate imaging using a 4-point Likert scale to measure IQ. As this was a service improvement study, the governance review of the protocol determined that individual patient consent was not required. A Caldecott review of the manuscript was undertaken to ensure ethical compliance.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patient selection and treatment

23 consecutive males with either local or locally advanced prostate cancer (Stages T2 and T3) to be treated with radiotherapy were studied. They were treated with our standard clinical protocol—74 Gy in 37 fractions delivered with volume modulated arc therapy, Elekta Agility™ linac (Elekta, Crawley, UK) using daily image guidance with CBCT (XVI, v. 4.5; Elekta, Crawley, UK) and soft-tissue matching. Males with hip replacements and post-operative patients were excluded from this study.

Dose protocols and measurement of image quality

We set up three imaging protocols in our Synergistiq®/XVI system (Mosaiq® v. 2.4; Elekta Ltd, Crawley, UK). The key parameters are given in Table 1. The nominal scan dose was measured using the method described in the XVI user manual.7 This uses a cylindrical phantom of 32 cm in diameter and 40 cm long. IQ was assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (4 = excellent, no artefacts; 3 = good, few artefacts; 2 = poor, just able to match; 1 = unsatisfactory, not able to match). This is the forced choice method of Likert scales which eliminates the neutral choice; effectively, the images are either suitable for matching or not. The scale was discussed with the radiographers who were performing the matching to ensure they understood it.

Table 1.

Cone beam CT exposure parameters for the exposure protocols used in this study

| Exposure protocol | “100%” | “80%” | “64%” |

|---|---|---|---|

| kV | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Frames | 660 | 660 | 660 |

| Nominal mA per frame | 64 | 64 | 50 |

| Nominal ms per frame | 40 | 32 | 32 |

| Nominal scan dose (mGy) | 29.6 | 23.7 | 18.5 |

Study protocol

The image matching and quality assessments were performed by the treatment unit–based radiographers as per our standard clinical practice. To be allowed to image match the radiographers all go through a competence-based training programme. Specifically, radiographers must demonstrate their ability to use all the imaging hardware and accompanying software. They must demonstrate and understand the importing and preparation process for imaging data ensuring it is appropriate for the task it is intended for. They must complete ten case studies for patients with prostate cancer which assesses their matching abilities and their decision-making abilities. They then demonstrate their abilities to the IGRT-lead radiographers before completing a competency statement. Image matching was performed by one radiographer and checked by a second radiographer prior to any table shifts being applied. They also agreed on the IQ score. This meant that owing to shift patterns that a particular subject had, the IQ was assessed by several different radiographers during the study. The total number of radiographers participating in the study, over its 5-month duration, was 26. Many of whom had more than 2 years' of experience of the image-matching process.

For each patient, the lateral separation at the level of the isocentre was measured on the planning CT scan. For the first 12 fractions, the CBCT scans used the “100%” exposure protocol; for the next 12 fractions, the CBCT scans used the “80%” exposure protocol; and for the final 13 fractions, the CBCT scans used the “64%” exposure protocol. The imaging protocol for each treatment fraction was set by independent superintendent radiographers, but the treatment radiographers were not blinded to the imaging protocol being used. The IQ was recorded for all CBCTs. If the CBCT scan was not useable for technical reasons (e.g. bowel gas), then this was addressed following standard department procedures, and the CBCT scan was repeated using the exposure protocol scheduled for that fraction. If the CBCT scan was not useable because of the IQ not being suitable for soft-tissue matching after the dose was reduced, then the CBCT scan was repeated with the exposure protocol that had been shown to give adequate IQ (e.g. if 64% proved to have unacceptable quality, then the 80% protocol was used). The remainder of the treatment fractions were then imaged using the higher dose protocol.

Statistical analysis

The median Likert score was calculated for each patient at each exposure level. The effect of the exposure level on IQ was analysed using the Freidman test with correction for ties. The data were then further analysed post hoc using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni adjustment for repetition. To determine the effect of patient lateral separation on IQ at the lowest exposure level used, we dichotomized the IQ scores into the categories IQ > 2 and IQ ≤ 2 and the point-biserial correlation coefficient calculated between the two categories and the lateral separation. Also we categorized the lateral separation into two categories; separations up to the lower quartile value and those above the lower quartile value. A χ2 test was used to compare the distribution of the two IQ categories at the lowest exposure level and the lower quartile separation with those above the lower quartile separation. These tests were performed in Excel® (Microsoft® Office 2010; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). p-values <0.05 were taken to be significant.

RESULTS

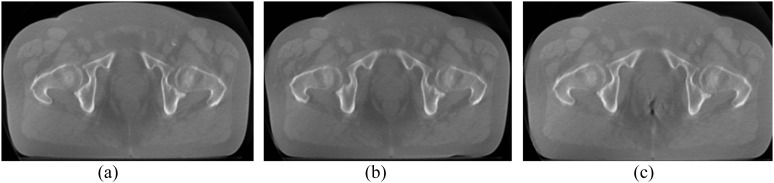

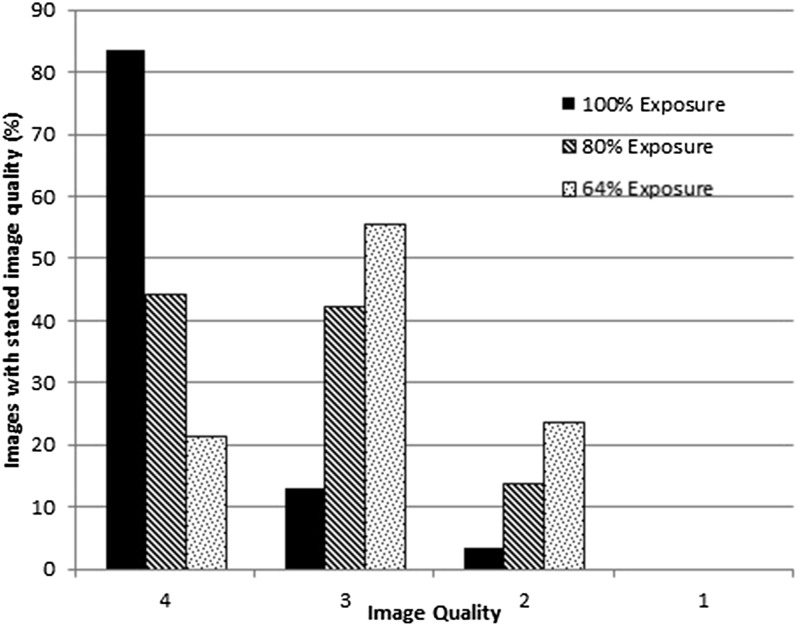

Example images at the different exposure levels/IQ are shown in Figure 1. The distribution of IQ with exposure level is shown in Figure 2. This demonstrates how the distribution of IQ changes with exposure level. None of the images were judged to be of unacceptable IQ owing to dose. However, the radiographers gave feedback that they felt that the “just acceptable”, IQ = 2 images, did take longer to match. The Friedman test gave a p-value of 2 × 10−7, with correction for ties. Hence, the relationship between the IQ and exposure protocol was very statistically significant for these patients. The post hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that IQ (100%) > IQ (80%) > IQ (64%) at the p = 0.005 level.

Figure 1.

An example cone beam CT of one subject taken at different exposure levels illustrating differences in image quality (IQ). (a) 100% exposure level, IQ = 4. (b) 80% exposure level, IQ = 3. (c) 64% exposure level, IQ = 2.

Figure 2.

The distribution of image quality as a function of the exposure level. As the exposure decreases, the proportion of lower quality images increases.

The range of lateral separations observed was 32.8–40.0 cm. The lower quartile value was 35.0 cm, with an interquartile range of 3 cm. When we dichotomized the “64%” exposure level into IQ > 2 and IQ ≤ 2, the point-biserial correlation coefficient was 0.045, indicating that the IQ and the lateral separation were not well correlated over the range of separations observed. However, the χ2 test showed that more images were in the lower IQ category for separations >35 cm (p = 0.002) for the “64%” exposure level.

DISCUSSION

Likert scales are used routinely in diagnostic radiology to determine subjective IQ.4–6 Their advantage is that they use the operators' experience to judge the suitability of the images to perform a particular task directly. However, we are not aware of their use in CBCT imaging in radiotherapy or them being specifically used to optimize IQ for soft-tissue matching in IGRT. We have used a simple 4-point scale to show in the clinical setting that exposure factors can be reduced by 20–36% from those that were supplied with the system and maintain usable IQ for the task of image matching.

The standard approach to optimizing CBCT IQ with respect to dose in radiotherapy is illustrated by two recent articles.1,8 Both have used a CatPhan™ phantom (The Phantom Laboratory, Salem, NY) to extensively investigate the variation of both low-contrast and high-contrast resolution with mAs per frame and the number of projections per CBCT. A potential limitation of these studies is that these used a CatPhan phantom rather than patients. A CatPhan phantom is a 15-cm diameter cylinder, not a realistic dimension for the male pelvis, and does not have the same inhomogeneity of contents as the human pelvis. It is designed to measure the physical parameters of IQ and is an excellent tool for investigating the dependence of these parameters on imaging conditions. We have used a sample of real patients to measure the subjective IQ as a function of dose for the actual clinical task. However, the results are quite similar. Loutfi-Krauss et al8 found that for the Elekta XVI® system (Elekta Ltd), the optimal mAs per frame for prostate CBCT was 1.6; our “64% exposure” protocol exactly has the same mAs per frame. They have reduced the number of projections to 377. We kept ours at the manufacturer provided value of 660. Our exposure is therefore slightly higher at 18.5 mGy than the 16.7 mGy of theirs. However, for patients with a lateral separation of >35 cm, we found that a higher exposure was required to maintain IQ for soft-tissue matching. For IQ optimization, the two approaches are complementary—phantom measurements indicate likely optimal imaging parameters and clinical studies translate these results into the clinical setting.

A limitation of the methods used in the study is that the treatment radiographers were not blinded to the imaging protocol being used. This may be acting as a confounding factor in the results. This may be mitigated to some extent by many radiographers contributing to the IQ assessment for individual subjects over the multiple imaging sessions.

We did not find a significant correlation between the IQ and the lateral separation. Theoretically, a correlation might be expected. The prostate, which is used in soft-tissue matching, is located at the centre of the patient. The dose to the prostate will decrease as the patient separation increases for constant exposure. This should decrease IQ. We may not have observed this, as the range of the separations that we observed was too small. The range of separations (33–40 cm) is quite limited and therefore limits our ability to determine the effect of patient separation. However, no patients outside this size range presented for treatment during the study period.

Another possibility is that for the task in hand, the IQ was more than sufficient, and any increased image noise due to reductions in dose with increasing separation was insufficient to affect the image-matching process. We did find that for separations <35 cm and the “64%” exposure parameters, there were a much lower proportion of IQ ≤ 2 than for separations >35 cm. We have altered our standard CBCT exposure parameters to the “80%” values for patients with separations >35 cm, and to the “64%” parameters for separations less than this value.

In this study there were no images with unusable IQ due to dose, but the radiographers performing the image matching gave feedback that some images had IQ approaching this level. We postulate that there is no sharp cut-off between acceptable and unacceptable IQ for this task. We suggest that as the IQ decreases, the certainty of matching decreases and the time to match the images increases. The visual acuity of trained staff enables them to match relatively low-quality images. This hypothesis requires confirmation with further research.

CONCLUSION

We can reduce exposure factors to 80% of those supplied with the system without hindering the matching process for all patients. For patients with lateral separations <35 cm, the exposure factors can be reduced further to 64% of the original values.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the therapy radiographers who participated in this study.

Contributor Information

Keith A Langmack, Email: keith.langmack@nuh.nhs.uk.

Louise A Newton, Email: Louise.Newton@nuh.nhs.uk.

Suzanne Jordan, Email: Suzanne.Jordan@nuh.nhs.uk.

Ruth Smith, Email: Ruth.Smith@nuh.nhs.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yan H, Cervino L, Jia X, Jiang SB. A comprehensive study on the relationship between the image quality and imaging dose in low-dose cone beam CT. Phys Med Biol 2012; 57: 2063–80. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/7/2063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Månsson LG. Methods for the evaluation of image quality: a review. Rad Prot Dosim 2000; 90: 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tapiovaara MJ. Review of relationships between physical measurements and user evaluation of image quality. Rad Prot Dosim 2008; 129: 244–8. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncn009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gebhard C, Fiechter M, Fuchs TA, Stehli J, Müller E, Stähli BE, et al. Coronary artery stents: influence of adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction on image quality using 64-HDCT. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 14: 969–77. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurung J, Khan MF, Maataoui A, Herzog C, Bux R, Bratzke H, et al. Multislice CT of the pelvis: dose reduction with regard to image quality using 16-row CT. Eur Radiol 2005; 15: 1898–905. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2720-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peltonen LI, Aarnisalo AA, Kortesniemi MK, Suomalainen A, Jero J, Robinson S. Limited cone-beam computed tomography imaging of the middle ear: a comparison with multislice helical computed tomography. Acta Radiol 2007; 48: 207–12. doi: 10.1080/02841850601080465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elekta. XVI User manual (1010070 02). Chapter 8. Crawley, UK: Elekta; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loutfi-Krauss B, Köhn J, Blümer N, Freundl K, Koch T, Kara E, et al. Effect of dose reduction on image registration and image quality for cone-beam CT in radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 2015; 191: 192–200. doi: 10.1007/s00066-014-0750-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]