Abstract

Objective:

Various clinical risk factors, including high breast density, have been shown to be associated with breast cancer. The utility of using relative and absolute area-based breast density-related measures was evaluated as an alternative to clinical risk factors in cancer risk assessment at the time of screening mammography.

Methods:

Contralateral mediolateral oblique digital mammography images from 392 females with unilateral breast cancer and 817 age-matched controls were analysed. Information on clinical risk factors was obtained from the provincial breast-imaging information system. Breast density-related measures were assessed using a fully automated breast density measurement software. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic (AUROC) curve was used to evaluate the performance of three cancer risk models: the first using only clinical risk factors, the second using only density-related measures and the third using both clinical risk factors and density-related measures.

Results:

The risk factor-based model generated an AUROC of 0.535, while the model including only breast density-related measures generated a significantly higher AUROC of 0.622 (p < 0.001). The third combined model generated an AUROC of 0.632 and performed significantly better than the risk factor model (p < 0.001) but not the density-related measures model (p = 0.097).

Conclusion:

Density-related measures from screening mammograms at the time of screen may be superior predictors of cancer compared with clinical risk factors.

Advances in knowledge:

Breast cancer risk models based on density-related measures alone can outperform risk models based on clinical factors. Such models may support the development of personalized breast-screening protocols.

INTRODUCTION

A number of clinical risk factors have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, including age, family history, menopausal status and use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT).1 However, given the reliance on subject recall, some of these self-reported risk factors can be of questionable validity, which can greatly influence the risk factor estimates obtained.2

Mammographic density (MD) is an area-based measure of the representation of the fibroglandular tissue in the breast on a mammogram and has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.1 Females with extremely dense breasts have been shown to be at 4–6 times higher risk of breast cancer than those with fatty breasts, making MD an important indicator of risk in the breast-screening process.3–5

MD can be quantified as a percent density (PD) or as an area-based density (AD). PD is a relative measure that quantifies the proportion of fibroglandular tissue as a percent, and AD is an absolute measure that quantifies the amount of fibroglandular tissue in mm2 or cm2. While it has been established that high MD is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, the contributions of PD and AD as predictors of breast cancer have not been as well established. Non-dense breast area and total breast area are two additional measures related to MD that can also be used in the prediction of breast cancer risk. All four of these measures of breast composition are displayed in Figure 1.

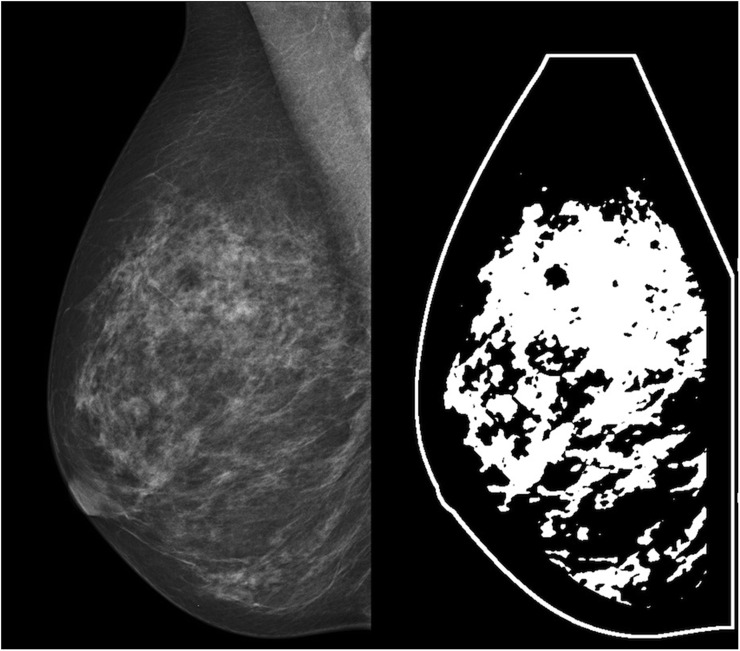

Figure 1.

The panel on the left shows a “for-presentation” mediolateral oblique full-field digital mammogram. The panel on the right shows a binary image that highlights the dense tissue within that same breast in white. Percent density is calculated as the ratio of area of the dense (white) tissue and the total area inside the breast outline, and area-based density is calculated simply as the area of the dense (white) tissue in mm2. Non-dense area is calculated as the total non-dense (black) area within the breast outline in mm2 and total area is calculated as the entire dense and non-dense area contained within the outline of the breast in mm2.

Because of the increased risk of breast cancer associated with high MD, females with dense breasts may be flagged for more frequent screening mammography. As personalized screening recommendations gain popularity, supplemental imaging protocols may be better defined by considering a female's personalized risk assessment alongside her breast density.6 However, many cancer risk models used in clinical practice, such as the Gail, Claus, BRCAPRO, BOADICEA and Rosner–Colditz models, do not include measures of MD.7 The standard method to measure MD is by visual assessment, and this method suffers from inter-rater and intrarater variability. Furthermore, the inclusion of a broad assessment of MD using categories following commonly used classification scales has not resulted in substantial gains in the predictive power of existing cancer risk models, potentially because categorical classification of MD assumes homogeneous risk within each group and results in a loss of power and inaccuracies in outcome estimation. In this regard, a precise measure of MD may offer an improvement over broad measures of MD.

It has been suggested that personalized breast cancer risk assessment at the time of screening mammography may be an ideal time to determine a female's risk of breast cancer and that this may be helpful in defining individualized screening recommendations. However, while this has been demonstrated to be feasible, there are limitations associated with the measurement and reliability of clinical risk factor data, and it has been shown that patients may not be able to recall all risk factor data when in clinic; thus, some data may need validation after the screening visit.7

With the availability of fully automated software algorithms, reliable and continuous density measures such as PD and AD as well as non-dense breast area and total breast area, which may be related to breast cancer aetiology, can now be included more easily in cancer risk models used at the time of screening and may play a significant role as predictors of breast cancer.8 To date, many cancer risk models that have been developed using only image-based features have been developed using small-sized samples or with “for-processing” images that are not routinely stored in clinic.

This study aimed to assess the utility of relative and absolute density-related measures from mammograms as an alternative to clinical risk factors in evaluating breast cancer risk at the time of screening mammography using the “for-presentation” images routinely stored in clinics.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Data source

The data used for this analysis were extracted from the provincial breast-imaging information system that supports the Nova Scotia Breast Screening Program (NSBSP). The NSBSP began in 1991 and since October 2008 has encompassed all screening mammography services in this Canadian province. The information system includes data for all breast imaging in the province as well as any histological findings associated with needle-core biopsy and surgical procedures that may be recommended as a result of an abnormal screen.

Study design and sample

A frequency-matched (1 : 2) case-control study design was employed. Cases and controls were sampled from within the population of females aged 40–75 years who underwent digital mammography through the NSBSP between 1 January 2009 and 30 June 2011. Case subjects were restricted to pathologically confirmed cases of unilateral screen-detected breast cancer. Two control subjects were randomly selected from within the screen-normal population and matched on age at screen within 1 year.

“For-presentation” mammograms for eligible cases and controls had been acquired from full-field digital mammography machines through the NSBSP. Contralateral mediolateral oblique digital mammography images were selected for the case group, and right-sided mediolateral oblique mammography images were selected for the control group.

Clinical risk factors

Data on clinical risk factors were obtained from the provincial breast-imaging information system. Risk factors included: age (years), number of births, HRT use at the time of screen (no/yes), first-degree family history of breast cancer (no/yes) and menopausal status (pre-menopausal/post-menopausal).

Density measures

A fully automated MD measurement software (DM-Research; Densitas Inc., Halifax, NS, Canada) was used to compute PD, AD, non-dense breast area and total breast area. The DM research algorithm uses the “for-presentation” images used by radiologists in clinic and has demonstrated excellent agreement with radiologists' visual assessments with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.91 (95% confidence interval: 0.89–0.92).9 The density-related measurement outputs used for analysis were: PD from 0% to 100%, AD in mm2 and non-dense breast area in mm2. Density-related measures were right skewed, and for the purposes of analysis, all measures were log transformed.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS® software v. 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A descriptive analysis of cases and controls on clinical risk factors and MD measures was conducted using means and standard deviations, or frequencies and proportions, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted and the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was used to evaluate the predictive performance of risk models based on relative and absolute MD measures separately from clinical factors; corresponding 95% Wald confidence intervals were computed. The AUROC of each of the models was compared with that of the other models and with that of the null model (no signal, AUROC = 0.5) using a non-parametric approach for comparing the area under two or more correlated receiver-operating characteristic curves.10 Three different multivariate models with unilateral screen-detected breast cancer as the dependent variable were evaluated and compared: the independent variables in the first model consisted only of clinical risk factors (age, number of births, HRT use at the time of screen, first-degree family history of breast cancer and menopausal status); those in second model consisted only of density-related measures (PD, AD and non-dense breast area); and those in the third model consisted of all independent variables from the clinical risk factor model and from the density-related measures model.

Ethical standards

This research was approved by the Capital District Health Authority Research Ethics Board and is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Informed consent was not obtained from participants as this study involved the secondary use of undistinguishable de-identified full-field digital mammography images and risk factor data.

RESULTS

A sample of 1272 subjects was identified (424 cases and 848 age-matched controls). 63 (4.95%) individual observations of the total 1272 observations were excluded from any analysis owing to missing risk factor data from the following variables: HRT use at time of screen, first-degree family history of breast cancer and menopausal status. After excluding cases with missing risk factor data, the final data set included 392 cases and 817 controls for the descriptive and multivariable logistic regression analyses. Results of the descriptive analysis can be found in Table 1. Case subjects and controls were similar in terms of clinical risk factors; however, the cases had a slightly higher mean PD, AD, non-dense breast area and total breast area than controls.

Table 1.

Description of patient characteristics for case and control subjects

| Patient characteristics | Cases (n = 392) | Controls (n = 817) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (standard deviation) | Mean (standard deviation) | |

| Age (years) | 58.9 (8.6) | 58.9 (8.6) |

| Number of births | 2.0 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.3) |

| Percent density (%) | 32.4 (15.6) | 29.2 (16.0) |

| Absolute density (mm2) | 5149.2 (2565.2) | 4219.9 (2423.4) |

| Non-dense breast area (mm2) | 12330.0 (6801.9) | 11709.2 (6282.8) |

| Total breast area (mm2) | 17479.2 (7351.3) | 15929.2 (6596.4) |

| Frequency (proportion) | Frequency (proportion) | |

| HRT use at time of screen | ||

| Yes | 43 (0.11) | 96 (0.12) |

| Family history of breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 120 (0.31) | 193 (0.24) |

| Menopausal status | ||

| Post-menopausal | 310 (0.79) | 644 (0.79) |

HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

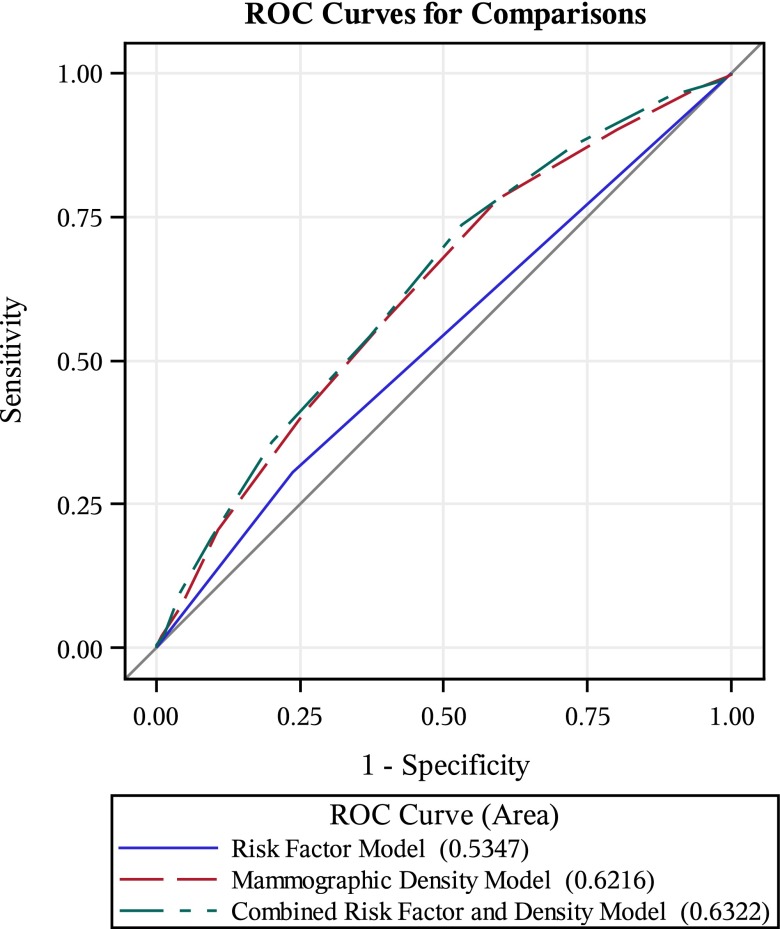

The first model, which modelled the association between screen-detected breast cancer risk and traditional clinical risk factors, generated an AUROC of 0.535 (0.499, 0.570). The second model, which modelled the association between screen-detected breast cancer risk and density-related features, generated an AUROC of 0.622 (0.589, 0.655). The third model, which modelled the association between screen-detected breast cancer risk and the risk factor variables from the first model in addition to the density-related measures from the second model, generated an AUROC of 0.632 (0.599, 0.665) (Figure 2). All three models performed significantly better than the null model (p < 0.001). Additionally, when comparing the AUROC of the first and second models, the density-related measures model performed significantly better than the model that incorporated only clinical risk factors (p < 0.001). The third model, which used independent variables from both the first two models, performed significantly better than the clinical risk factor model (p < 0.001) but did not perform significantly better than the density-related measures model (p = 0.097). These results are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves show that the mammographic density model performs better than the risk factor model, and that the combined risk factor and density model does not perform better than the mammographic density model.

Table 2.

Summary of observed area under the receiver-operating characteristic (AUROC) curve values

| Model or contrast of models | AUROCa or Δ AUROC | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Null (no signal) | 0.5000 | – |

| Risk factorsb | 0.5347 | – |

| Breast density relatedc | 0.6216 | – |

| Combinedd | 0.6322 | – |

| Risk factors vs null | 0.0347 | 0.0512 |

| Breast density related vs null | 0.1216 | <0.001 |

| Combined vs null | 0.1322 | <0.001 |

| Breast density related vs risk factors | 0.0869 | <0.001 |

| Combined vs risk factors | 0.0975 | <0.001 |

| Combined vs breast density related | 0.0106 | 0.0971 |

With the exception of the null model, all models used unilateral screen-detected breast cancer (no/yes) as the dependent variable.

The risk factors model included age (years), number of births, hormone replacement therapy use at time of screen (no/yes), first-degree family history of breast cancer (no/yes) and menopausal status (pre-menopausal/post-menopausal) as independent variables.

The breast density-related model included percent density from 0% to 100%, area density in mm2 and non-dense breast area in mm2 as independent variables.

The combined model included all independent variables from the risk factors model as well as all independent variables from the breast density-related model.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this study indicate that breast cancer risk models that incorporate relative and absolute measurements of MD as well as measures of non-dense breast area from “for-presentation” screening mammograms at the time a female is screened may provide a better alternative to using clinical risk factors as predictors for assessing breast cancer risk at the time of screening mammography. In our study, a clinical risk factor-based model demonstrated poor discrimination despite a well-established association between traditional clinical risk factors and breast cancer risk. However, MD-related measures can both provide a more accurate prediction of breast cancer than clinical risk factors and be routinely measured in clinical settings using reliably reproducible fully automated methods that are becoming more widely available.

While the discriminatory ability of the models presented in this article is modest based on the observed AUROC values, such models can be useful in a clinical setting. For example, the AUROC of the Gail model commonly reported in the literature is 0.58.11 A computerized implementation of this breast cancer risk-assessment tool is used in clinics 20,000 to 30,000 times a month, and breast cancer prevention treatment is often based on Gail model risk scores.11,12 It is therefore necessary and appropriate to study cancer risk models with low AUROC values. The Tyrer–Cuzick model has demonstrated improved predictive performance over the Gail model on a given sample of females; however, the Tyrer–Cuzick model requires much more self-reported data to be collected for inclusion in the model, and the acquisition of this volume of data can be burdensome in the clinical setting.7 This study proposes a breast cancer risk model that may perform just as well as or better than the current standard of the Gail model and that would be simple to implement at the time of screening mammography using “for-presentation” images. The predictive power of the cancer risk model proposed in this study may be improved by adding additional image-based features and is the subject of future research.

The population-wide nature of the sample and the use of a standardized and reliable method to assess relative and absolute density-related measures make these results robust and reliable. This study does not include body mass index (BMI) because it is not measured as part of the NSBSP activities due to resource constraints and is not collected based on self-reporting owing to known limitations in self-reported height and weight data. BMI has been shown to be inversely associated with PD.13 However, the inclusion of AD and non-dense breast area in the density-related model counters this information deficit: AD is not confounded by BMI and the non-dense breast area is highly correlated with both BMI and weight and has been used in other research as an acceptable objective surrogate measure for BMI, which itself is often underestimated when self-reported.14 Future research could benefit from evaluating the performance of breast cancer risk models using density-related measures as an alternative to BMI.

Improved risk estimates derived from MD-related measures may be useful for tailoring individual screening protocols that lead to more strategic use of healthcare resources.15 In the context of modest performance of risk models such as the Gail model that are already in clinical use, the potential to improve performance using image features from “for-presentation” digital mammograms is an advancement over the current practice. Our findings provide a basis for future research in applying image analysis methods that may further improve risk model performance by inclusion of new image-based features from “for-presentation” images.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the Radiology Research Office in the Department of Diagnostic Imaging at the Nova Scotia Health Authority for their ongoing support during this research.

Contributor Information

Mohamed Abdolell, Email: mo@dal.ca.

Kaitlyn M Tsuruda, Email: k.tsuruda@gmail.com.

Christopher B Lightfoot, Email: cblightf@dal.ca.

Jennifer I Payne, Email: jennifer.payne@dal.ca.

Judy S Caines, Email: jscaines@dal.ca.

Sian E Iles, Email: iles@dal.ca.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

M Abdolell is the founder and CEO of Densitas Inc. KM Tsuruda is an employee of Densitas Inc.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Dalhousie University; the Radiology Research Foundation and the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, NS, Canada; and the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation-Atlantic Region.

REFERENCES

- 1.McPherson K, Steel CM, Dixon JM. Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors, and genetics. BMJ 2000; 321: 624–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan E. Recall bias can be a threat to retrospective and prospective research designs. Internet J Epidemiol 2006; 3: 4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 227–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisson J, Diorio C, Mâsse B. Wolfe’s parenchymal pattern and percentage of the breast with mammographic densities redundant or complementary classifications? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003; 12: 728–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15: 1159–69. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, Sprague BL, Tice JA, Lehman CD, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer. Ann Int Med 2015; 162: 673–81. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans DG, Howell A. Can the breast screening appointment be used to provide risk assessment and prevention advice? Breast Cancer Res 2015; 17: 84. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0595-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettersson A, Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Tamimi RM. Nondense mammographic area and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2011; 13: R100. doi: 10.1186/bcr3041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdolell M, Tsuruda KM, McDougall EE, Iles S, Lightfoot C, Caines J. Towards personalized breast screening protocols: validation of mammographic density estimation from full-field digital mammograms. Vienna, Austria: European Congress of Radiology; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988; 44: 837–45. doi: 10.2307/2531595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rockhill B, Spiegelman D, Byrne C, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA. Validation of the Gail et al. model of breast cancer risk prediction and implications for chemoprevention. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93: 358–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vachon CM, van Gils CH, Sellers TA, Ghosh K, Pruthi S, Brandt KR, et al. Mammographic density, breast cancer risk and risk prediction. Breast Cancer Res 2007; 9: 217. doi: 10.1186/bcr1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam PB, Vacek PM, Geller BM, Muss HB. The association of increased weight, body mass index, and tissue density with the risk of breast carcinoma in Vermont. Cancer 2000; 89: 369–75. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone J, Ding J, Warren RM, Duffy SW, Hopper JL. Using mammographic density to predict breast cancer risk: dense area or percentage dense area. Breast Cancer Res 2010; 12: R97. doi: 10.1186/bcr2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakes RW, Duffy SW, Ng FC, Gao F, Ng EH. Mammographic parenchymal patterns and risk of breast cancer at and after a prevalence screen in Singaporean women. Int J Epidemiol 2000; 29: 11–19. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]