Abstract

Background

The epidemiology of gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has not been adequately characterized. Using United States Renal Data System data we investigated the epidemiology of GIB in hospitalized patients receiving long-term dialysis.

Methods

Medicare ESRD patients who began dialysis between 1996 and 2005 were followed from 90 days after starting dialysis to death, transplant, loss of Medicare, or December 31, 2006. GIB events were identified using claims data. Predictors of GIB incidence were analyzed using over-dispersed Poisson regression and Cox regression was used to evaluate the effect on survival. Repeat episodes were modeled using a partially conditional Cox regression model.

Results

406,836 patients were followed for 832,131 person-years, during which 133,967 events were identified. The incidence of GIB was stable through year 2000 but steadily increased thereafter. Chronic gastric ulcer and colonic diverticulosis were the commonest defined causes of upper and lower GIB respectively. Age >49 years, female gender, hypertension as the cause of ESRD, and initiation on hemodialysis was associated with a greater risk of GIB. An episode of GIB conferred a increased hazard of death (hazard ratio 1.9, 95 % CI 1.86–1.93). A previous episode of GIB was associated with greater hazard of another episode (hazard ratio 3.93, 95 % CI 3.82–4.05).

Conclusions

In ESRD patients incident to long-term dialysis the incidence of hospital-associated GIB is increasing, is associated with a greater hazard of death, and carries a great hazard of repeat episodes.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal bleeding, End-stage renal disease, Mortality, Dialysis

Background

Subjects on long-term dialysis represent an ever-expanding patient population with a much higher morbidity and mortality compared to the general population. Besides a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease, small studies have shown there is an increased incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in this patient population [1, 2]. However, the true incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in this population is not known [3].

In the United States, peritoneal dialysis has been in a steady decline while the incidence of hemodialysis has been rising [4]. Since heparin-based anticoagulation is used during hemodialysis the question arises whether the expanding hemodialysis population is prone to greater gastrointestinal bleeding risks. Our anecdotal observations suggest gastrointestinal bleeding episodes have increased in the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) population.

In summary, the epidemiology of gastrointestinal bleeding in long-term dialysis subjects has not been adequately characterized. Prior studies have been solely related to upper gastrointestinal bleeding and often limited to outcomes during hospitalization [5–10]. It is of interest to determine if gastrointestinal bleeding episodes have any impact other than morbidity i.e. whether they impact mortality in ESRD subjects. Since ESRD subjects already have a high burden of cardiovascular disease it is rational to consider that added insults like gastrointestinal bleeding could increase the risk of death.

We hypothesized that in patients with end-stage renal disease receiving long-term dialysis the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding has increased over time, carries a high risk of repeated bleeding episodes, and is associated with increased risk of death. Using United States Renal Data System data we studied the epidemiology of gastrointestinal bleeding in hospitalized patients on long-term dialysis.

Methods

The United States Renal Data System (USRDS) was used to identify incident dialysis subjects with non-HMO Medicare as primary payer and first date of ESRD service between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2005. The USRDS is the national data system funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases that collects, analyzes, and distributes information about ESRD in the United States. USRDS receives data about all Medicare claims from the Centers of Medicare and Med-icaid services for all patients on chronic dialysis in the United States with Medicare as primary payer, which represents about 80 % of patients on long-term dialysis [11]. For patients younger than 65 years who are not disabled Medicare coverage for center dialysis patients typically starts 90 days after the first dialysis service while for home dialysis patients coverage starts immediately. Thus, for uniformity, the study time for each patient started 90 days after the date of first service, which is the accepted methodology for outcome analyses using USRDS data [12]. This avoids incomplete hospitalization data from center hemodialysis patients aged younger than 65 years and not disabled, who cannot bill Medicare until 90 days after first ESRD service date. Further, since type of dialysis could impact the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding patients with unknown dialysis type were not included. The patients were followed up to the first occurrence of death, transplant, loss of Medicare as primary payer, recovery of kidney function, unknown dialysis type, loss to follow-up, or December 31, 2006.

Gastrointestinal bleeding episodes were identified from Medicare claims data of all hospitalization events with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes related to gastrointestinal bleeding. We a priori considered bleeding at sites anatomically proximal to the ligament of Treitz as upper gastrointestinal bleeding and at distal locations lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Analytical methods

An initial analysis of predictors of the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was performed using over-dispersed Poisson regression with log-person years as offset on a six-way cross-tabulation of the number of bleeding events by current age, sex, race, primary cause of renal failure, initial type of dialysis, and current year. Additionally, we evaluated the cumulative incidence of the first occurrence of a gastrointestinal bleeding event using the Nelson-Aalen estimator. For this analysis death and transplant were treated as competing events, and patients were censored at the date of last follow up, loss of Medicare as primary payer, recovery of renal function, when the type of dialysis was unknown, or at the end of the study period (December 31, 2006).

A Cox regression model was used to evaluate the effect of bleeding on survival. Sex, race, primary cause of renal failure, and year of first service were included as baseline predictors; current age, current dialysis type, and occurrence of bleeding during the follow-up period were included as time-varying covariates.

The process of repeat gastrointestinal bleeding episodes was modeled using a partially conditional Cox regression model. The time was restarted after each bleeding occurrence, thus the probability of reoccurrence was modeled. Robust sandwich estimators were used to account for the within-patient dependence of the gastrointestinal bleeding episodes. The number of previous episodes was treated as strata for graphical presentation. For a numerical estimate of the effect of previous gastrointestinal bleeding episodes on subsequent ones a modified model was fitted with two additional covariates, an indicator of having had any gastrointestinal bleeding and the number of additional bleeding episodes.

Most analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), with the exception of the cumulative incidence estimation performed using the “cmprsk” package in R 3.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided 5 % significance level was used throughout. Wherever applicable, results are reported as mean (standard deviation).

Results

A total of 406,836 incident dialysis patients were identified and followed for 832,131 person-years. 133,967 gastrointestinal bleeding events were identified for a rate of 161 events per 1,000 person-years. The mean age of the patient population was 66.9 (14.4), 52.5 % were men, and the majority (67 %) were whites. Overall about 19.5 % of the population had at least one gastrointestinal bleeding episode associated with a hospitalization event. Patients with bleeding episodes had an average of 1.69 (1.44) bleeding events (range 1–44). Defined upper gastrointestinal bleeding events were more common (65.2 events per 1,000 patient-years) than lower gastrointestinal bleeding events (33.7 events per 1,000 patient-years). Patients with defined upper gastrointestinal bleeding episodes had an average of 1.51 (1.13) episodes and patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding episodes had an average of 1.27 (0.76) episodes. As the population age increased, the overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding increased. However, among the defined categories the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding progressively decreased with age while that of lower gastrointestinal bleeding progressively increased. For example, in the 0–39 year-old age group the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding was 82.7 events per 1,000 person-years and that of lower gastrointestinal bleeding was 8.4 per 1,000 person-years. In the 80 years and older age group the incidence of diagnosed upper GI bleeding was 58.4 events per 1,000 person-years and that of lower GI bleeding was 47.7 per 1,000 person-years. While in a large percent of instances (38.6 %) the source of bleeding was not defined chronic gastric ulcer was the commonest cause among episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (6.4 % of cases) and diverticulosis of the colon was the commonest cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (6.2 % of cases). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population and Table 2 shows the distribution of the various causes of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Predictor | Category | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (at first ESRD service) | 0–39 | 22,799 | 5.60 |

| 40–49 | 30,526 | 7.50 | |

| 50–59 | 54,495 | 13.39 | |

| 60–69 | 99,039 | 24.34 | |

| 70–79 | 132,933 | 32.67 | |

| 80+ | 67,044 | 16.48 | |

| Sex | Male | 213,465 | 52.47 |

| Female | 193,371 | 47.53 | |

| Race | White | 272,620 | 67.01 |

| Black | 113,794 | 27.97 | |

| Other | 20,422 | 5.02 | |

| Cause of ESRD | Diabetes | 194,652 | 47.85 |

| Hypertension | 118,388 | 29.10 | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 28,293 | 6.95 | |

| Other | 65,503 | 16.10 | |

| Year of first service | 1996–1997 | 87,642 | 21.54 |

| 1998–1999 | 90,016 | 22.13 | |

| 2000–2001 | 88,536 | 21.76 | |

| 2002–2003 | 80,708 | 19.84 | |

| 2004–2005 | 59,934 | 14.73 | |

| Initial dialysis modality | HD | 374,891 | 92.15 |

| PD | 31,945 | 7.85 | |

| Any GI bleeding | None | 327,488 | 80.50 |

| Yes | 79,348 | 19.50 | |

| Documented upper GI bleeding | None | 370,854 | 91.16 |

| Yes | 35,982 | 8.84 | |

| Documented lower GI bleeding | None | 384,827 | 94.59 |

| Yes | 22,009 | 5.41 |

ESRD end-stage renal disease, HD hemodialysis, PD peritoneal dialysis

Table 2.

Distribution of the causes of gastrointestinal bleeding in the patient population

| Type | Etiology | ICD-9-CM code | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 133,967 | 100.00 | ||

| Upper GI bleeding | Acute duodenal ulcer with hemorrhage | 532.xx | 1,471 | 1.1 |

| Acute gastric ulcer with hemorrhage | 531.xx | 2,144 | 1.6 | |

| Acute gastritis with hemorrhage | 535.01 | 1,898 | 1.42 | |

| Acute gastrojejunal ulcer with hemorrhage | 534.xx | 57 | 0.04 | |

| Acute peptic ulcer with hemorrhage | 533.xx | 121 | 0.1 | |

| Alcoholic gastritis with hemorrhage | 535.31 | 49 | 0.04 | |

| Angiodysplasia of stomach and duodenum with hemorrhage | 537.83 | 3,688 | 2.75 | |

| Atrophic gastritis with hemorrhage | 535.11 | 1,335 | 1.00 | |

| Chronic duodenal ulcer with hemorrhage | 532.xx | 5,281 | 3.94 | |

| Chronic gastric ulcer with hemorrhage | 531.xx | 8,540 | 6.37 | |

| Chronic or unspecified gastrojejunal ulcer with hemorrhage | 534.xx | 199 | 0.15 | |

| 535.61 | 1,737 | 1.30 | ||

| Chronic peptic ulcer with hemorrhage | 533.xx | 816 | 0.61 | |

| Dieulafoy lesion (hemorrhagic) of stomach and duodenum | 537.84 | 352 | 0.26 | |

| Esophageal hemorrhage | 530.82 | 2,970 | 2.22 | |

| Esophageal varices with bleeding | 456.0 | 366 | 0.27 | |

| Esophageal varices with bleeding in diseases classified elsewhere | 456.20 | 901 | 0.67 | |

| Gastric mucosal hypertrophy with hemorrhage (hypertrophic gastritis) | 535.21 | 25 | 0.02 | |

| Gastroesophageal laceration-hemorrhage syndrome (Mallory-Weiss syndrome) | 530.7 | 3,136 | 2.34 | |

| Hematemesis | 578.0 | 7,868 | 5.87 | |

| Other specified gastritis with hemorrhage | 535.41 | 5,412 | 4.04 | |

| Ulcer of the esophagus with bleeding | 530.21 | 831 | 0.62 | |

| Unspecified gastritis and gastroduodenitis with hemorrhage | 535.51 | 5,059 | 3.78 | |

| Lower GI bleeding | Angiodysplasia of intestine with hemorrhage | 569.85 | 4,480 | 3.34 |

| Dieulafoy lesion (hemorrhagic) of intestine | 569.86 | 60 | 0.04 | |

| Diverticulitis of colon with hemorrhage | 562.13 | 1,467 | 1.10 | |

| Diverticulitis of small intestine with hemorrhage | 562.03 | 13 | 0.01 | |

| Diverticulosis of colon with hemorrhage | 562.12 | 8,338 | 6.22 | |

| Diverticulosis of small intestine with hemorrhage | 562.02 | 102 | 0.08 | |

| Acute vascular insufficiency of intestine | 557.0 | 6,682 | 4.99 | |

| Hemorrhage of rectum and anus | 569.3 | 6,911 | 5.16 | |

| Unspecified source | Hemorrhage of gastrointestinal tract, unspecified | 578.9 | 35,592 | 26.57 |

| Occult blood in stool | 792.1 | 2,215 | 1.65 | |

| Blood in stool | 578.1 | 13,844 | 10.33 |

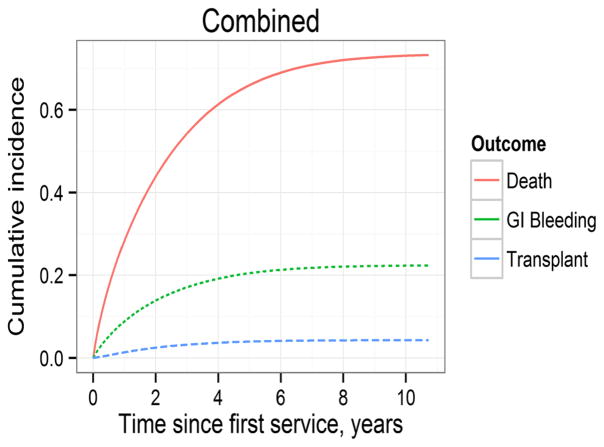

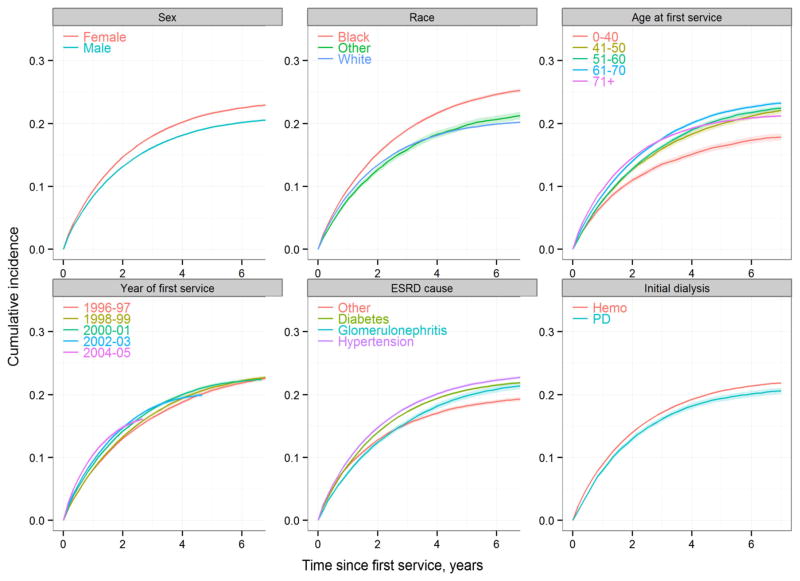

Marginal analyses showed that the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in hospitalized ESRD patients was more or less stable in the late 1990s and then steadily increased thereafter. During the period 1996–2000 the incidence fluctuated on either side of 130 events per 1,000 person-years. Year 2000 onwards depicted a consistent year-to-year rise in the incidence such that in year 2006 the incidence was 221.2 events per 1,000 person-years (Table 3). Adjusted analyses showed that the relative risk of a hospital-associated gastrointestinal bleeding episode significantly rose from year 2001 through 2006 and in year 2006 was 62 % greater than in year 1996. The incidence also steadily increased with age (progressively in each age decile beyond age 49 compared to persons aged 39 years or younger), was significantly greater in women, and in blacks versus whites. Among the predominant causes of ESRD, the incidence was greater in patients with hypertensive ESRD than in those with ESRD due to diabetes mellitus. The risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was lower in patients who initiated ESRD therapy with peritoneal dialysis as compared to patients who initiated hemodialysis therapy. Table 4 shows the results of the Poisson regression analyses. Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of the first gastrointestinal bleeding event along with the cumulative incidence of transplantation and death. Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding according to various characteristics.

Table 3.

Bleeding events according to various characteristics

| Characteristic | Category | Total number of GI bleeding events | GI bleeding events per 1,000 person- years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 133,967 | 161.0 | |

| Age | 0–39 | 5,433 | 130.0 |

| 40–49 | 9,296 | 139.6 | |

| 50–59 | 16,980 | 143.0 | |

| 60–69 | 31,769 | 158.0 | |

| 70–79 | 46,570 | 171.7 | |

| 80+ | 23,919 | 180.2 | |

| Sex | Male | 66,140 | 154.0 |

| Female | 67,827 | 168.5 | |

| Race | White | 79,393 | 155.3 |

| Black | 48,230 | 175.5 | |

| Other | 6,344 | 138.2 | |

| Etiology of ESRD | Diabetes | 64,901 | 159.5 |

| Hypertension | 41,537 | 170.9 | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 9,236 | 143.1 | |

| Other | 18,293 | 155.5 | |

| Initial modality | HD | 125,321 | 162.7 |

| PD | 8,646 | 139.6 | |

| Year | 1996 | 1,518 | 131.9 |

| 1997 | 5,538 | 128.0 | |

| 1998 | 8,809 | 129.6 | |

| 1999 | 11,384 | 134.3 | |

| 2000 | 13,466 | 140.3 | |

| 2001 | 15,761 | 153.1 | |

| 2002 | 16,881 | 160.4 | |

| 2003 | 17,197 | 167.5 | |

| 2004 | 17,470 | 186.9 | |

| 2005 | 15,527 | 201.2 | |

| 2006 | 10,416 | 221.2 |

ESRD end-stage renal disease, HD hemodialysis, PD peritoneal dialysis

Table 4.

Adjusted risk of gastrointestinal bleeding events in incident dialysis patients

| Variable | Comparison | Documented upper GI bleeding

|

Documented lower GI bleeding

|

Any GI bleeding

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | (95 % CI) | RR | (95 % CI) | RR | (95 % CI) | ||

| Age (years) | 40–49 vs 0–39 | 0.85 | (0.8–0.91) | 1.86 | (1.63–2.11) | 1.04 | (0.99–1.1) |

| 50–59 vs 0–39 | 0.75 | (0.7–0.79) | 2.63 | (2.34–2.96) | 1.06 | (1.01–1.11) | |

| 60–69 vs 0–39 | 0.73 | (0.69–0.77) | 3.82 | (3.41–4.28) | 1.18 | (1.13–1.24) | |

| 70–79 vs 0–39 | 0.72 | (0.68–0.76) | 4.97 | (4.44–5.56) | 1.29 | (1.23–1.35) | |

| 80+ vs 0–39 | 0.67 | (0.63–0.71) | 5.32 | (4.74–5.96) | 1.32 | (1.26–1.38) | |

| Sex | Female vs male | 0.96 | (0.94–0.98) | 1.31 | (1.28–1.34) | 1.07 | (1.05–1.09) |

| Race | Black vs White | 1.14 | (1.11–1.17) | 1.22 | (1.19–1.25) | 1.16 | (1.14–1.19) |

| Other vs White | 0.89 | (0.84–0.94) | 0.82 | (0.77–0.87) | 0.91 | (0.87–0.95) | |

| Etiology of ESRD | Hypertension vs diabetes | 0.93 | (0.9–0.95) | 1.23 | (1.19–1.26) | 1.03 | (1.01–1.05) |

| GN vs diabetes | 0.79 | (0.76–0.84) | 1.23 | (1.17–1.29) | 0.95 | (0.91–0.98) | |

| Other vs diabetes | 0.83 | (0.8–0.86) | 1.17 | (1.13–1.22) | 1.00 | (0.97–1.02) | |

| Initial modality | PD vs HD | 0.98 | (0.94–1.03) | 0.82 | (0.78–0.87) | 0.93 | (0.9–0.96) |

| Year | 1997 vs 1996 | 1.01 | (0.89–1.14) | 0.87 | (0.76–0.99) | 0.96 | (0.88–1.05) |

| 1998 vs 1996 | 0.98 | (0.87–1.1) | 0.9 | (0.79–1.02) | 0.97 | (0.89–1.06) | |

| 1999 vs 1996 | 0.97 | (0.86–1.09) | 0.94 | (0.83–1.06) | 1.00 | (0.92–1.09) | |

| 2000 vs 1996 | 0.99 | (0.88–1.11) | 0.98 | (0.87–1.11) | 1.04 | (0.96–1.13) | |

| 2001 vs 1996 | 1.08 | (0.97–1.22) | 1.06 | (0.94–1.2) | 1.14 | (1.05–1.23) | |

| 2002 vs 1996 | 1.14 | (1.01–1.27) | 1.11 | (0.99–1.25) | 1.19 | (1.09–1.29) | |

| 2003 vs 1996 | 1.19 | (1.06–1.33) | 1.15 | (1.02–1.3) | 1.24 | (1.14–1.34) | |

| 2004 vs 1996 | 1.4 | (1.25–1.57) | 1.31 | (1.16–1.47) | 1.38 | (1.27–1.49) | |

| 2005 vs 1996 | 1.52 | (1.35–1.7) | 1.44 | (1.27–1.62) | 1.48 | (1.36–1.61) | |

| 2006 vs 1996 | 1.48 | (1.31–1.66) | 1.61 | (1.42–1.82) | 1.62 | (1.49–1.76) | |

ESRD end-stage renal disease, GN glomerulonephritis, HD hemodialysis, PD peritoneal dialysis

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, transplantation and death in patients incident to long-term dialysis

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in incident dialysis patients with various characteristics

Cox regression analysis showed that an episode of hospital-associated gastrointestinal bleeding in patients incident to long-term dialysis had a significant adverse impact on survival increasing the hazard of death by almost two-fold (hazard ratio 1.9, 95 % confidence intervals 1.86–1.93). Every additional episode of gastrointestinal bleeding increased the hazard of death by an additional 3 %. Table 5 shows the hazard of death associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and other factors.

Table 5.

Mortality associated with gastrointestinal bleeding events and other factors

| Predictor | Comparison | Hazard ratio for death | 95 % CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one bleeding episode vs none | 1.898 | 1.86–1.93 | < 0.0001 | |

| Each additional bleeding episode | 1.030 | 1.02–1.04 | < 0.0001 | |

| Age | 40–49 vs under 40 | 1.191 | 1.16–1.22 | < 0.0001 |

| 50–59 vs under 40 | 1.347 | 1.32–1.38 | < 0.0001 | |

| 60–69 vs under 40 | 1.574 | 1.54–1.61 | < 0.0001 | |

| 70–79 vs under 40 | 1.884 | 1.84–1.93 | < 0.0001 | |

| 80+ vs under 40 | 2.374 | 2.32–2.43 | < 0.0001 | |

| Sex | Female vs male | 0.977 | 0.97–0.98 | < 0.0001 |

| Race | Black vs White | 0.830 | 0.82–0.84 | < 0.0001 |

| Other vs White | 0.836 | 0.82–0.85 | < 0.0001 | |

| Etiology of ESRD | Hypertension vs diabetes | 0.923 | 0.92–0.93 | < 0.0001 |

| Glomerulonephrophritis vs diabetes | 0.783 | 0.77–0.79 | < 0.0001 | |

| Other vs diabetes | 1.061 | 1.05–1.07 | < 0.0001 | |

| Year of first service | 1998–1999 vs 1996–1997 | 1.125 | 1.11–1.14 | < 0.0001 |

| 2000–2001 vs 1996–1997 | 1.294 | 1.28–1.31 | < 0.0001 | |

| 2002–2003 vs 1996–1997 | 1.626 | 1.61–1.64 | < 0.0001 | |

| 2004–2005 vs 1996–1997 | 2.316 | 2.29–2.35 | < 0.0001 | |

| Initial modality PD vs HD | 1.147 | 1.13–1.16 | < 0.0001 | |

ESRD end-stage renal disease, HD hemodialysis, PD peritoneal dialysis

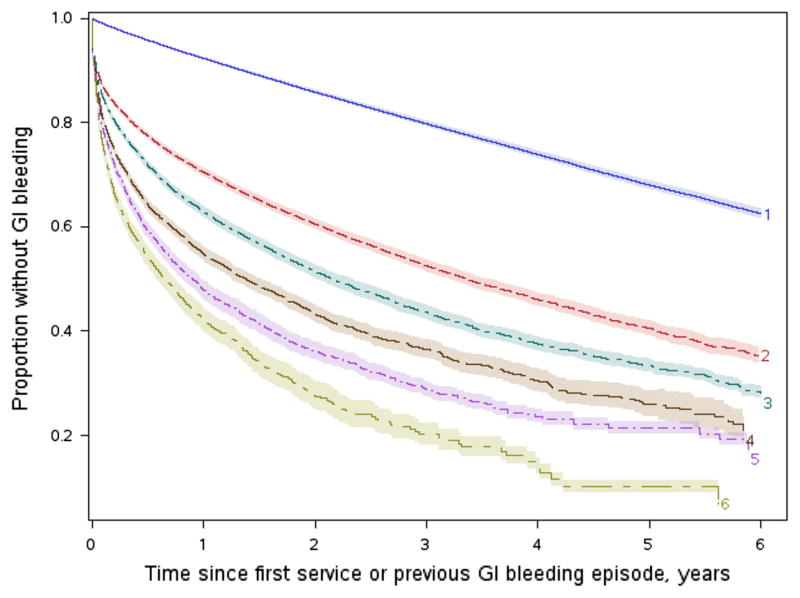

The hazard of repeated episodes of gastrointestinal bleed steadily increased with age (progressively in each decile beyond age 40 years or more), was greater in women, and in persons with hypertension as the cause of ESRD (Table 6). Furthermore, the incidence of repeated episodes of bleeding steadily increased with calendar years of incidence, with a significantly greater hazard of re-bleeding after year 2002. Having had a previous episode of GIB increased the hazard of another episode substantially (hazard ratio 3.933; 95 % CI 3.82–4.05), and each further bleed kept increasing the future hazard (hazard ratio 1.114; 95 % CI 1.10–1.13). After each episode of gastrointestinal bleeding, the proportion of patients with bleed-free survival at given time-points progressively decreased. As a representative example, Fig. 3 depicts the progressively smaller proportion of bleed event-free survivors at given times after each of six consecutive episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding in a reference population (white men under 40 years of age, end-stage renal disease due to diabetes mellitus, incident to dialysis in period 1996–1997).

Table 6.

Predictors of repeated episodes gastrointestinal bleeding in incident dialysis patients

| Predictor | Comparison | Hazard ratio | 95 % CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior GI bleeding | At least one bleeding episode vs none | 3.933 | 3.82–4.05 | < 0.0001 |

| Age | 40–49 vs under 40 | 1.066 | 0.99–1.10 | 0.0087 |

| 50–59 vs under 40 | 1.101 | 1.05–1.15 | < 0.0001 | |

| 60–69 vs under 40 | 1.196 | 1.14–1.25 | < 0.0001 | |

| 70–79 vs under 40 | 1.279 | 1.23–1.34 | < 0.0001 | |

| 80+ vs under 40 | 1.327 | 1.27–1.39 | < 0.0001 | |

| Sex | Female vs male | 1.047 | 1.03–1.06 | < 0.0001 |

| Race | Black vs White | 1.085 | 1.07–1.10 | < 0.0001 |

| Other vs White | 0.925 | 0.91–0.94 | < 0.0001 | |

| Etiology of ESRD | Hypertension vs diabetes | 1.017 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.0258 |

| Glomerulonephritis vs diabetes | 0.936 | 0.92–0.96 | < 0.0001 | |

| Other vs diabetes | 1.001 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.9301 | |

| Current year | 1998–1999 vs 1996–1997 | 0.979 | 0.96–1.00 | 0.0791 |

| 2000–2001 vs 1996–1997 | 1.049 | 1.02–1.08 | 0.0001 | |

| 2002–2003 vs 1996–1997 | 1.133 | 1.11–1.16 | < 0.0001 | |

| 2004–2005 vs 1996–1997 | 1.284 | 1.25–1.32 | < 0.0001 | |

| 2006 vs 1996–1997 | 1.648 | 1.59–1.71 | < 0.0001 | |

| Modality | Current PD vs HD | 0.987 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.3085 |

ESRD end-stage renal disease, HD hemodialysis, PD peritoneal dialysis

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients with gastrointestinal bleed-free survival at various time points (x-axis) after first six episodes of bleeding; e.g. top curve represents the proportion with bleed-free survival after the first episode of bleeding, second curve similar proportion after the second bleed, and so on (shaded areas represent 95 % confidence intervals) In a reference group of white males under 40 years of age, incident to dialysis in 1996–1997 with diabetes mellitus as the cause of end-stage renal disease

Discussion

After remaining more or less stable in the latter part of the twentieth century, the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with end-stage renal disease beginning long-term dialysis that occurs during hospitalization or results in hospitalization has been steadily increasing. Moreover, these gastrointestinal bleeding events associated with an increased hazard of death. It is possible a gastrointestinal bleeding occurrence increases the risk of cardiovascular events in patients on dialysis due to the associated the hemodynamic insult or decline in hemoglobin. Such factors could well place additional strain on patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis therapy who inherently have a vulnerable cardiovascular milieu and high burden of atherosclerotic disease.

The factors that have led to an increasing incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on long-term dialysis are not clear. It is tempting to speculate that the incidence of gastrointestinal bleed has increased due to rising number and proportion of patients receiving hemodialysis and the declining numbers of patients on peritoneal dialysis. For instance, in 1996, 65,533 incident ESRD patients began hemodialysis while 9,356 (proportion 12.5 %) patients began peritoneal dialysis. In 2006 incident hemodialysis patients equaled 101,549 while incident peritoneal dialysis patient equaled 6,773 (proportion 6.7 %) [4]. About two-thirds of hemodialysis patients have detectable levels of heparin in pre-dialysis plasma samples suggesting a chronic state of anticoagulation [13]. However, the effect of dialysis type while statistically significant was not large and the rising incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was seen even after adjustment for initial dialysis modality indicating modality trends over time is not an adequate explanation. Another factor that could be playing a part in recent increase in gastrointestinal bleeding could be related to advancement of cardiovascular intervention in recent years and increasing use of antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel. However the authors are unaware of any data in support of such a premise.

A three-fold hazard of re-bleeding episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding, that occur during another hospitalization or result in another hospitalization, in this patient population is noteworthy. Given these data representing overt re-bleeding, subclinical rates of re-bleeding might be even greater. Fluctuations in hemoglobin are common in dialysis subjects, often ascribed to a phenomenon referred to as hemoglobin cycling [14–16]. However, a higher index of suspicion of gastrointestinal blood loss may be warranted in patients with prior known bleeding episodes during downward drifts in hemoglobin. Further investigation is merited to ascertain the predictive value of degrees of decline in hemoglobin in detecting recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding.

A higher observed hazard of mortality associated with hospital-associated gastrointestinal bleeding episodes in patients on long-term dialysis suggests that such instances might warrant a different approach as compared to the general population. In usual circumstances, in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding without hemodynamic compromise or relatively stable hemoglobin endoscopy is often undertaken on a non-urgent basis often depending on the time or day of presentation. There is generally no uniformity of approach and gastroenterologists treat each instance of bleeding on a case by case basis based on clinical judgment. The question arises whether subjects on dialysis merit a different and more aggressive tactic. Further study is necessary to ascertain whether more aggressive intervention such as uniformly early endoscopy leads to better outcomes in patients on long-term dialysis hospitalized with gastrointestinal bleeding.

Our study elucidated important results in a large population showing the prominence of chronic gastric ulcer and diverticulosis of the colon as the most common defined causes of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in the study population. Further, demographic patterns of the risk of bleeding and repeated bleeding detected in the present analysis offers valuable insights for clinicians taking care of this patient population.

There are limitations of the present study. Firstly, we only analyzed gastrointestinal bleeding events that led to hospitalization or occurred during a hospitalization stay. Episodes of bleeding that were not associated with a hospital stay were not captured. However, it is likely that in ESRD patients a meaningful bleeding episode that leads to a substantive drop in hemoglobin or hemodynamic change would result in an inpatient diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding. Arguably, given these results, even trivial episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding in this population should be given greater importance and the threshold for hospitalization should possibly be different. However, one cannot be certain that trivial episodes would have a similar impact on outcome. While the analysis adjusted for key variables it is possible that factors unaccounted for could affect the results. Particularly, we did not have data regarding antithrombotic agents, including oral anticoagulants. In the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study population, oral anticoagulant use has been shown to be associated with a higher risk of overall bleeding events requiring hospitalization in patients on chronic hemodialysis though specifically gastrointestinal bleeding-related outcomes were not reported [17]. Moreover, we only analyzed dialysis patients with Medicare as a primary payer. However, there is no reason to suspect that outcomes of gastrointestinal bleeding would vary in non-Medicare patients. Like any registry data, our results are fraught with the limitation that they are dependent on appropriate coding and appropriate data entry. Furthermore, if a billing claim is not submitted we would not capture that episode, a situation we consider less likely due to the inherent interest in capturing revenue appropriately on the part of health care providers. Due to the large number of subjects in the study and the large of number of events captured, which have enabled a robust analysis, we feel that such missed or erroneous data is not likely to substantially alter the interpretation or overall conclusions.

In conclusion the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding that occur during hospitalization or result in hospitalization is increasing in patients with end-stage renal disease new to long-term dialysis and carries a high hazard of recurrence. Chronic gastric ulcer and colonic diverticulosis are the commonest causes of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding respectively. Besides leading to greater morbidity episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding are associated with a greater hazard of death. There needs to be awareness of this issue and a more aggressive approach to such bleeding episodes might be warranted in this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Agnes Libot, MD for help in identifying ICD-9-CM codes of gastrointestinal bleeding and Qun Xiang, MS for help in statistical analysis. Support received by grant 8UL1TR000055 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Footnotes

The results were presented at annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology in Atlanta, Georgia on November 9, 2013 and published in abstract form in the abstract edition of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Conflict of interest On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Hariprasad Trivedi, Email: haritriv7@gmail.com, Divison of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, 9200 W. Wisconsin Ave., CLCC 5220, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA.

Juliana Yang, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Aniko Szabo, Division of Biostatistics, Institute for Health and Society, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

References

- 1.Luo J-C, Leu H-B, Huang K-W, Huang C–C, Hou M-C, Lin H-C, Lee F-Y, Lee S-D. Incidence of bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers in patients with end-stage renal disease receiving hemodialysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:E1345–E1351. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo J-C, Leu H-B, Hou M-C, Huang K-W, Lin H-C, Lee F-Y, Chan W-L, Lin S-J, Chen J-W. Nonpeptic ulcer, non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding in hemodialysis patients. Am J Med. 2013;126:264.e25–264.e32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toke AB. GI bleeding risk in patients undergoing dialysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:50–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2013 annual data report. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sood P, Kumar G, Nanchal RA, Ahmad S, Ali M, Kumar N, Ross EA. Chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease predict higher risk of mortality in patients with primary upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:216–224. doi: 10.1159/000336107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung J, Yu A, LaBossiere J, Zhu Q, Fedorak RN. Peptic ulcer bleeding outcomes adversely affected by end-stage renal disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasse H, Gillen DL, Ball AM, Kestenbaum BR, Seliger SL, Sherrard D, Stehman-Breen CO. Risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding among end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1455–1461. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C-Y, Wu M-S, Kuo KN, et al. Long-term peptic ulcer rebleeding risk estimation in patients undergoing haemodialysis: a 10-year nationwide cohort study. Gut. 2011;60:1038–1042. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo CC, Kuo HW, Lee IM, Lee CT, Yang CY. The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with hemodialysis: a population-based cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parasa S, Navaneethan U, Sridhar AR, Venkatesh PG, Olden K. End-stage renal disease is associated with worse outcomes in hospitalized patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih YT. [Accessed 23 Jan 2014];Effect of insurance on prescription drug use by ESRD beneficiaries. 2014 https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/downloads/99springpg39.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Researcher’s guide. [Accessed 21 Jan 2014];2014 http://www.usrds.org/2013/rg/A_intro_sec_1_13.pdf.

- 13.Kaneva K, Bansal V, Hoppensteadt D, Cunanan J, Fareed J. Variations in the circulating heparin levels during maintenance hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2013;19:449–452. doi: 10.1177/1076029613479820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishbane S, Berns JS. Hemoglobin cycling in hemodialysis patients treated with recombinant human erythropoietin. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1337–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbertson DT, Ebben JP, Foley RN, Weinhandl ED, Bradbury BD, Collins AJ. Hemoglobin level variability: associations with mortality (2008) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:133–138. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01610407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selby NM, Fonseca SA, Fluck RJ, Taal MW. Hemoglobin variability with epoetin beta and continuous erythropoietin receptor activator in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2012;32:177–182. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2010.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sood MM, Larkina M, Thumma JR, et al. Major bleeding events and risk stratification of antithrombotic agents in hemodialysis: results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2013;84:600–608. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]