ABSTRACT

Crawling cells can generate polarity for migration in response to forces applied from the substratum. Such reaction varies according to cell type: there are both fast- and slow-crawling cells. In response to periodic stretching of the elastic substratum, the intracellular stress fibers in slow-crawling cells, such as fibroblasts, rearrange themselves perpendicular to the direction of stretching, with the result that the shape of the cells extends in that direction; whereas fast-crawling cells, such as neutrophil-like differentiated HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells, which have no stress fibers, migrate perpendicular to the stretching direction. Fish epidermal keratocytes are another type of fast-crawling cell. However, they have stress fibers in the cell body, which gives them a typical slow-crawling cell structure. In response to periodic stretching of the elastic substratum, intact keratocytes rearrange their stress fibers perpendicular to the direction of stretching in the same way as fibroblasts and migrate parallel to the stretching direction, while blebbistatin-treated stress fiber-less keratocytes migrate perpendicular to the stretching direction, in the same way as seen in HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells. Our results indicate that keratocytes have a hybrid mechanosensing system that comprises elements of both fast- and slow-crawling cells, to generate the polarity needed for migration.

KEYWORDS: amoeboid movement, cell migration, cell polarity, cell stretch, crawling cells, mechanosensing, stress fibers, traction forces, trajectory analysis

Introduction

Cell crawling plays an essential role in most organisms throughout their life.1-3 For instance, in the developmental stage, embryonic cells migrate en masse to form organs and tissues. In adults, epithelial cells migrate across open wounds to close them for healing,4-6 and neutrophils hunt and kill bacteria.7,8 Fast-crawling cells migrate toward chemoattractants such as N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine (fMLP) in the case of neutrophils and neutrophil-like HL-60 cells,9,10 and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) in the case of Dictyostelium cells.11-13 Interestingly, even in media containing a uniform concentration of fMLP, HL-60 cells localize actin filaments to a portion of the cell and myosin IIA or RhoA to the opposite side to enable migration.14,15 Dictyostelium cells also can localize phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, which plays a role in the generation of migrating polarity, at a portion of the cell even in media containing a uniform concentration of cAMP16-18 and migrate while regarding the portion as front. These observations suggest that migrating cells can generate their own polarity and migrate in a chosen direction, even in the absence of a concentration gradient of an attractive substance. How these crawling cells generate polarity for migration is an interesting question. Crawling cells obviously cannot migrate without adhering to the substratum, from which they receive mechanical stimuli that dictate their shape and/or migration properties.19,20

To test the role of the mechanical interaction between cell and substratum in polarity generation for cell migration, one of the most useful techniques is to periodically stretch and relax the elastic substratum to which the cells adhere.21-25 Using this technique, unidirectional mechanical stimuli can be continuously applied to the cells from the substratum. In response to this periodic stretching of the elastic substratum, in slow-crawling cells such as fibroblasts, as well as endothelial, osteosarcoma, and smooth muscle cells, the intracellular stress fibers are rearranged perpendicular to the stretching direction, and the shape of the cells extends in that direction.26-32 In neutrophil-like differentiated HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells, which have no stress fibers, and which show fast-crawling migration, periodic stretching of the elastic substratum makes them migrate perpendicular to the direction of stretching.33,34 The chief cause of this directional migration was revealed by trajectory analysis, which is a powerful tool for identifying the behavioral strategy that crawling cells adopt for survival.35-37 According to trajectory analysis, the main trigger for perpendicular migration of HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells appears to be not the difference in migration velocity between the perpendicular direction and parallel direction, but a greater probability of a switch to perpendicular migration.33

Fish epidermal keratocytes are epidermal wound-healing cells in fish skin38-40 that show fast-crawling behavior similar to HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells.41 Each cell is composed of a frontal crescent-shaped lamellipodium and a rear spindle-shaped cell body. They maintain their arc-shaped front edge during crawling migration.42-45 Unlike HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells, however, they have stress fibers, which are structures typically seen in slow-crawling cells, in their cell body.46-49 The orientation of the stress fibers in the keratocyte cell body is always perpendicular to the direction of migration.

The question investigated in this paper is how keratocytes migrate in response to periodic stretching: whether they migrate perpendicular to the stretching direction like other fast-crawling cells such as HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells, or rearrange their stress fibers perpendicular to the stretching direction, as do slow-crawling cells, and migrate parallel to the stretching direction. To study this question, we dispersed keratocytes from a goldfish, Carassius auratus, on elastic sheets made from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and subjected them to periodic stretching stimuli. We then analyzed their trajectories. Trajectory analysis revealed a unique characteristic of keratocytes, i.e., intact keratocytes rearrange their stress fibers perpendicular to the direction of stretching, like fibroblasts, and migrate parallel to the stretching direction. However, blebbistatin-treated stress fiber-less keratocytes migrated perpendicular to the stretching direction, in the same way as seen in HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells. Our results therefore suggest that keratocytes have 2 distinct mechanosensing mechanisms: one that depends on stress fibers and one which does not, to generate the necessary polarity for migration.

Results

Intact keratocytes migrate parallel to the stretching direction

Keratocytes from a goldfish, Carassius auratus, were transferred to an elastic PDMS sheet whose surface was coated with collagen. Periodic stretching stimuli were applied by repeated stretching and relaxation of the sheet. In all the experiments, time cycle, and duty ratio of stretching and relaxation were adjusted to 5 s and 1:1, respectively. While the sheet was being stretched, perpendicular shrinkage was suppressed to ≤1/4 of the stretch, as in the case of previous studies.23,33,34 Images were transferred to a PC at 30-s intervals for 30 minutes.

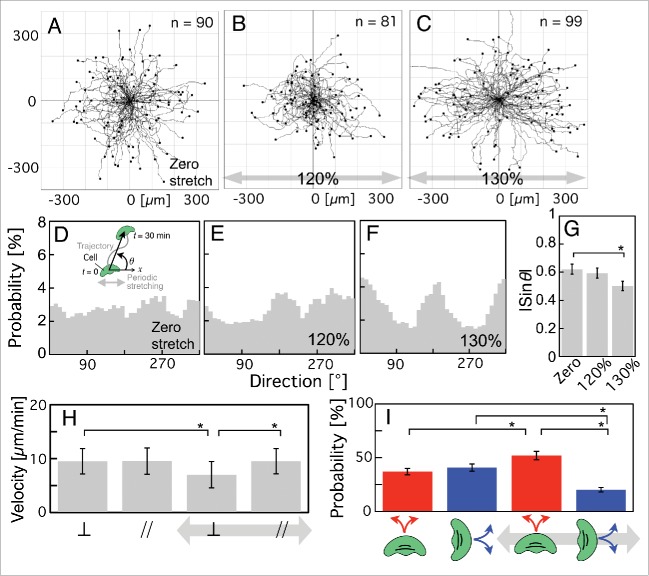

First, periodic stretching stimuli were applied to intact keratocytes. The trajectories of cell migration given zero stretching stimulus and those under periodic stretching stimuli are shown in Figure 1A–C. Periodic stretching stimuli with a 120% or a 130% stretch ratio were applied parallel to the x-axis in Figure 1B and C, respectively. The probability of each direction of migration (θ; inset in Fig. 1D; see Materials and methods for full details) was respectively calculated from Figure 1A–C (Fig 1D–F). The cells tended to migrate parallel to the direction of stretching (0° or 180°) when subjected to periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio (Fig. 1C, F and Movie S1), whereas they migrated randomly in its absence (Fig. 1A and D) and when subjected to periodic stretching with a 120% stretch ratio (Fig. 1B and E). The absolute value of the sine of the angle, |sinθ|, was calculated from Figure 1A–C to provide an index of directional migration (Fig. 1G). If all cells migrate parallel to the direction of stretching (0° or 180°; hereinafter “parallel (migration)”), all the values of |sinθ| should be 0. On the other hand, if all cells migrate perpendicularly (90° or 270°; hereinafter “perpendicular (migration)”), the value should be 1. If they show random migration, the value should be 2/π = 0.64. (See Materials and methods for full details.) The value for cells subjected to periodic stretching stimuli with a 130% stretch ratio (Fig. 1G, right) is significantly lower than for those given zero stretching stimulus (Fig. 1G, left), although there was no significant difference in the value between those with a 120% stretch ratio (Fig. 1G, middle) and those given zero stretching stimulus (Fig. 1G, left), indicating that keratocytes can sense periodic stretching stimuli with a ≥130% stretch ratio applied through the substratum and migrate parallel to the stretching direction. These results suggest that keratocytes that prefer a deformed direction differ from other fast-crawling cells such as HL-60 cells (|sinθ| = 0.84 ± 0.02 (SEM), 30% stretching ration and 15 s time cycle)33 and Dictyostelium (|sinθ| = 0.80 ± 0.037 (SEM), 30% stretching ration and 10 s time cycle).23,33,34

Figure 1.

Migrations of intact keratocytes on an elastic substratum given zero stretching stimulus or when subjected to periodic stretching with a 5-s time cycle for 30 min. (A–C) Trajectories given zero stretching stimulus (A, n = 90 from 10 experiments) and when subjected to periodic stretching with a 120% stretch ratio (B, n = 81 from 6 experiments) and a 130% stretch ratio (C, n = 99 from 8 experiments). Periodic stretching stimuli were applied parallel to the x-axis in B and C (gray arrows). (D–F) Probability of migration direction (θ; inset in D) calculated from A–C, respectively. The angle (θ) was made by the x-axis and the vector from the initial location of a cell (t = 0 min) to the final one during observation (t = 30 min) (see Materials and methods for details). (G) The |sinθ| values calculated from A (left column), B (middle column) and C (right column), respectively. (H) Migration velocities on elastic substratum calculated from A and C. The two left-hand columns and 2 right-hand columns respectively represent velocities under zero stretching stimulus and under periodic stretching stimuli with a 130% stretch ratio. The velocities perpendicular and parallel to the stretching direction are indicated as ⊥ and //, respectively. (I) Probability of a switch of migration direction on the elastic substratum, calculated from A (2 left-hand columns) and C (2 right-hand columns). The red and blue columns respectively represent the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel and vice versa. The bars in G and I, and H indicate SEM and SD, respectively. The p-values were calculated using Student's t-test. *p < 0.05.

How do these cells realize directional migration parallel to the stretching direction? There are 2 possible origins of directional migration. One is that the migration velocity parallel to the stretching direction is higher than that in any other direction. The other is that the probability of a switch of migration direction to parallel to the stretching direction is greater than that of a switch to other directions. To test whether the migration velocity parallel to the stretch direction is higher than that perpendicular to it, we calculated them given zero stretching stimulus and under periodic stretching stimuli with a 130% stretch ratio by analysis of the trajectories of Figure 1A and C at 120-s intervals. (See Materials and methods for full details.) With zero stretching stimulus (the 2 left-hand columns in Fig. 1H), there was no significant difference in the velocity between the perpendicular direction (left ⊥ in Fig. 1H) and the parallel direction (left // in Fig. 1H). When periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio was applied (the 2 right-hand columns in Fig. 1H), the velocity perpendicular to the stretch direction was significantly decreased (compare the ⊥ columns in Fig. 1H), although that parallel to the stretch direction did not change (compare the // columns in Fig. 1H). As a result, under periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio, the velocity parallel to the stretch direction (right // column in Fig. 1H) was significantly greater than that perpendicular to the stretch direction (right ⊥ column in Fig. 1H).

Next, to investigate whether the probability of a switch of migration direction from perpendicular to parallel is higher than that from parallel to perpendicular, we analyzed the trajectories of keratocytes given zero stretching stimulus (Fig. 1A) and under periodic stretching stimuli with a 130% stretch ratio (Fig. 1C) and calculated the probability of a switch of migration direction from perpendicular to parallel (red columns in Fig. 1I) and that from parallel to perpendicular (blue columns in Fig. 1I) at 120-s intervals. (See Materials and methods for full details.) With zero stretching stimulus, there was no significant difference in the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel (left red column in Fig. 1I), or vice versa (left blue column in Fig. 1I), although the left blue column is a little taller than the left red one. When periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio was applied, the probability of a switch from parallel to perpendicular significantly decreased (compare the blue columns in Fig. 1I), although that from perpendicular to parallel increased (compare the red columns in Fig. 1I). Our results show that under periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio, the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel (right-hand red column in Fig. 1I) was significantly greater than that from parallel to perpendicular (right-hand blue column in Fig. 1I).

These results suggest that (i) a decrease in the velocity in the perpendicular direction, (ii) an increase in the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel, and (iii) a decrease in the probability of a switch from parallel to perpendicular are the causes of migration parallel to the stretching direction.

Here, we found that periodic stretching stimuli with a ≤120% stretch ratio does not affect the migration-direction of keratocytes. Thus, in all the following experiments, we applied those with a 130% stretch ratio.

Jasplakinolide-treated keratocytes migrate in random direction under periodic stretching stimuli

Judging by migration velocity alone, keratocytes should be a type of fast-crawling cell, as are neutrophils and Dictyostelium cells. However, keratocytes migrated parallel to the stretching direction despite the fact that neutrophil-like differentiated HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells migrate perpendicular to it.23,33,34 The most notable difference in the cytoskeleton between keratocytes and the other fast-crawling cells is likely to be the presence or absence of stress fibers. Stress fibers may play an important role in the directional migration parallel to the stretching direction.

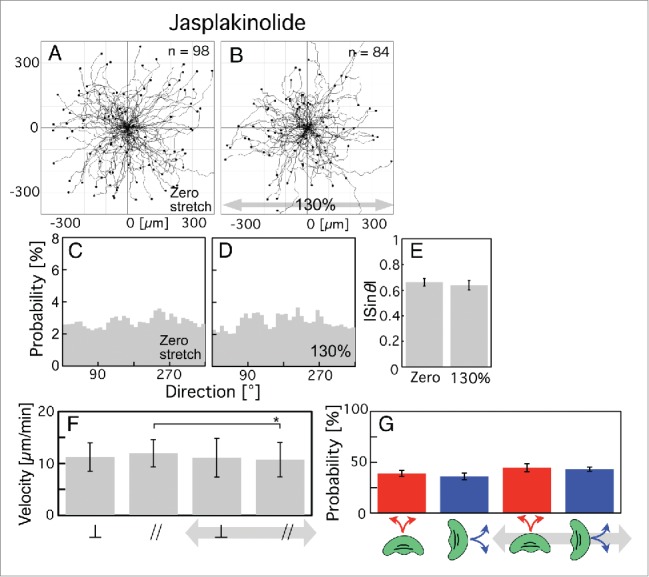

Under periodic stretching stimuli, stress fibers in slow-crawling cells such as fibroblasts are rearranged perpendicular to the direction of stretching.26-32 The cause of this reaction is thought to be the depolymerization of stress fibers aligned parallel to the direction of stretching by the binding of the actin-severing protein cofilin.50,51 To test whether the depolymerization of stress fibers in response to the periodic stretching stimuli is required for the directional migration of keratocytes, we treated them with jasplakinolide, which inhibits the depolymerization of stress fibers composed of actin filaments. We then applied periodic stretching stimuli. The trajectories of cell migration given zero stretching stimulus and under periodic stretching stimuli are shown in Figure 2A and B, respectively. The probability of each direction of migration (θ) (Fig. 2C and D) was respectively calculated from Figure 2A and B. The cells migrated randomly, irrespective of the presence or absence of stretching stimuli (Fig. 2A-D). The |sinθ| values calculated from Figure 2A and B are shown in Figure 2E. There was no significant difference in the values of the cells given zero stretching stimulus (Fig. 2E, left) and under periodic stretching stimuli (Fig. 2E, right).

Figure 2.

Migrations of jasplakinolide-treated keratocytes on elastic substratum given zero stretching stimulus or when subjected to periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio and 5-s time cycle for 30 min. (A and B) Trajectories of cells given zero stretching stimulus (A, n = 98 from 8 experiments) and when subjected to periodic stretching (B, n = 84 from 7 experiments). Periodic stretching stimuli were applied parallel to the x-axis in B (gray arrow). (C and D) Probability of migration direction (θ) calculated from A and B, respectively. The angle (θ) was made by the x-axis and the vector from the initial location of a cell (t = 0 min) to the final location during observation (t = 30 min) (see Materials and methods for details). (E) The |sin θ| values calculated from A (left column) and B (right column), respectively. (F) Migration velocities on the elastic substratum calculated from A and B. The two left-hand columns and 2 right-hand columns respectively represent velocities given zero stretching stimulus and under periodic stretching stimuli. The velocities perpendicular and parallel to the stretching direction are indicated as ⊥ and //, respectively. (G) Probability of a switch of migration direction on the elastic substratum, calculated from A (2 left-hand columns) and B (2 right-hand columns). The red and blue columns respectively represent the switching probabilities from perpendicular to parallel and vice versa. The bars in E and G, and F indicate SEM and SD, respectively. The p-values were calculated using Student's t-test. *p < 0.05.

We then compared the migration velocity of cells perpendicular to the stretch direction and that parallel to it given zero stretching stimulus and under periodic stretching stimuli by analysis of the trajectories of Figure 2A and B at 120-s intervals. With zero stretching stimulus, there was no significant difference in the velocity between the perpendicular direction (left ⊥ in Fig. 2F) and the parallel direction (left // in Fig. 2F). When periodic stretching was applied (2 right-hand columns in Fig. 2F), the velocity parallel to the stretching direction showed a statistically significant decrease (compare the // columns in Fig. 2F). However, the decrease was very small, and there was no significant difference in the velocity between movement in the perpendicular direction (right ⊥ in Fig. 2F) and movement in the parallel direction (right // in Fig. 2F) under periodic stretching.

Next, we calculated the probability of a switch of migration direction from perpendicular to parallel (red columns in Fig. 2G) and that from parallel to perpendicular (blue columns in Fig. 2G) at 120-s intervals from the trajectories of Figure 2A and B. With zero stretching stimulus, there was no significant difference in the probability of a switch between perpendicular to parallel (left red column in Fig. 2G) or vice versa (left blue column in Fig. 2G). Application of periodic stretching changed neither the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel (compare the red columns in Fig. 2G) nor that from parallel to perpendicular (compare the blue columns in Fig. 2G), although the right blue column is a little taller than the left blue one. As a result, under periodic stretching as well, there was no significant difference in the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel (right-hand red column in Fig. 2G) or vice versa (right-hand blue column in Fig. 2G).

Stress fibers in keratocytes subjected to periodic stretching stimuli

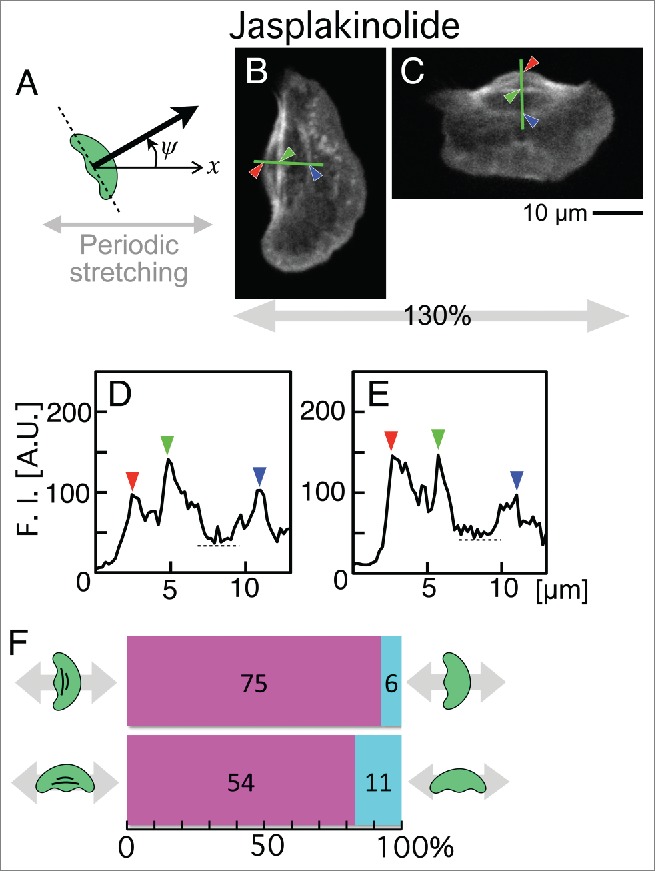

To test the depolymerization of stress fibers that had been inhibited by the application of jasplakinolide throughout the application of periodic stretching stimuli, jasplakinolide-treated cells were fixed after periodic stretching for 30 minutes and stained with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin. The relationship between the migration direction of the cells and the presence or absence of the stress fibers was then statistically analyzed (Fig. 3). In this analysis, the migration direction (thick arrow in Fig. 3A) was determined as the direction perpendicular to the long axis of the cell (dotted line in Fig. 3A). When the angle (ψ) between the x-axis (x in Fig. 3A) and the thick arrow was between 315 (–45) and 45° or between 135 and 225°, the migration direction was labeled as “parallel” to the direction of stretching, and when it was 45 – 135° or 225 – 315°, it was labeled as “perpendicular” to the direction of stretching.

Figure 3.

Presence or absence of stress fibers in jasplakinolide-treated keratocytes on elastic substratum after stretching with a 130% stretch ratio and 5-s time cycle for 30 min. (A) Definition of migration direction (ψ) (see text for details). When ψ was between 315 (–45) and 45° or between 135 and 225°, the migration direction was labeled as “parallel” to the stretching direction. When it was 45 – 135° or 225 – 315°, it was labeled as “perpendicular.” (B and C) Distribution of stress fibers in typical cells migrating parallel (B) and perpendicular (C) to the direction of stretch. Actin filaments were stained with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin. Images B and C are typical of 81 and 65 cells, respectively. (D and E) Fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin along the green lines in B (D) and C (E), respectively. Left and right peaks (red and blue arrowheads) indicate the accumulated actin filaments at the rear end of the cell (red arrowheads in B and C), and at the boundary of cell body and lamellipodium (blue arrowheads in B and C), respectively. When the middle peaks (green arrowheads in D and E) whose intensity is higher than 150% of the minimum intensity in the cell body (dotted lines in D and E) were detected (green arrowheads in B and C), the cell was defined to retain stress fibers. (F) Numbers of cells with stress fibers (magenta) and without (cyan). Top: Cells migrating parallel to the direction of stretch. Bottom: Cells migrating perpendicular to the direction of stretch.

Figure 3B and C are typical cells migrating parallel and perpendicular to the direction of stretch, respectively. Fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin along the green lines in Figure 3B and C are shown in Figure 3D and E, respectively. The peaks indicated by red and blue arrowheads in Figure 3D and E are equivalent to the accumulated actin filaments at the rear end of the cell (red arrowheads in Fig. 3B and C) and those at the boundary of cell body and lamellipodium (blue arrowheads in Fig. 3B and C), respectively. When the middle peaks (green arrowheads in Fig. 3D and E) whose intensity is higher than 150% of the minimum intensity (dotted lines in Fig. 3D and E) in the cell body were detected (green arrowheads in Fig. 3B and C), the cells were defined to retain stress fibers. Under periodic stretching stimuli, 75 of 81 cells whose migration direction was parallel to the stretching direction retained their stress fibers (Fig. 3F, top). On the other hand, 54 of 65 cells whose direction was perpendicular to it also retained them (Fig. 3F, bottom).

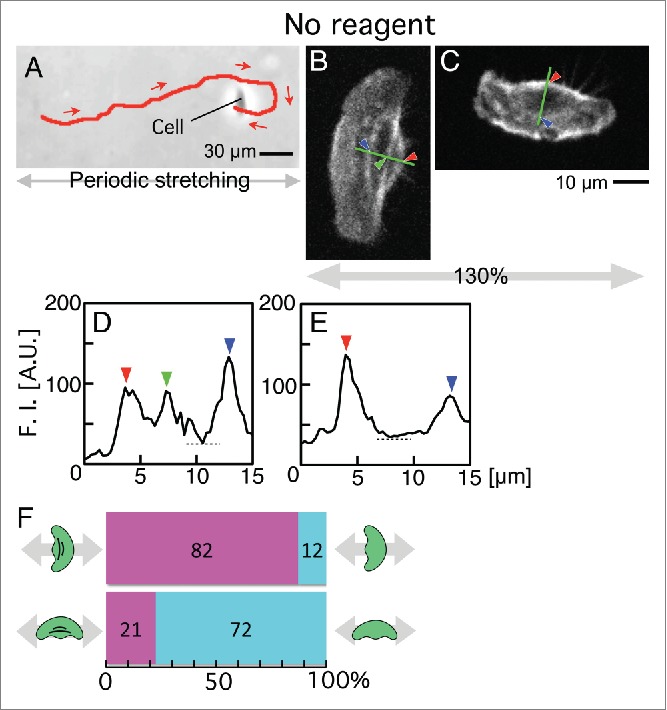

The presence or absence of stress fibers was also measured in the intact keratocytes after periodic stretching. In response to periodic stretching stimulation, intact keratocytes migrated not straight along the stretching direction but showed a fluctuating migratory direction. An enlarged view of a typical trajectory from Figure 1B is shown in Figure 4A. This indicates that some cells can be fixed in the state in which they are moving perpendicular to the stretching, and we can compare the presence and absence of stress fibers between cells traveling perpendicular to the stretching direction and cells traveling parallel to the stretching direction. Figure 4B and C are typical cells migrating parallel and perpendicular to the direction of stretch, respectively. Fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin along the green lines in Figure 4B and C are shown in Figure 4D and E, respectively. When subjected to periodic stretching stimuli, 82 of 94 cells whose migration direction was parallel to the stretching direction retained their stress fibers (Fig. 4F, top). On the other hand, 72 of 93 cells whose direction was perpendicular to the stretching direction lost their stress fibers (Fig. 4F, bottom).

Figure 4.

Presence or absence of stress fibers in intact keratocytes on the elastic substratum after periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio and 5-s time cycle for 30 min. The migration direction was determined in Figure 3A. (A) A typical trajectory (red line) of an intact keratocyte on the elastic substratum under periodic stretching for 30 min, extracted from Figure 1C. Red arrows indicate the migration direction. (B and C) Distribution of stress fibers in typical cells migrating parallel (B) and perpendicular (C) to the direction of stretch. Actin filaments were stained with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin. Images B and C are typical of 94 and 93 cells, respectively. (D and E) Fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin along the green lines in B (D) and C (E), respectively. Cells with stress fibers were defined in the same manner as in Figure 3D and E. (F) Numbers of cells with stress fibers (magenta) and without (cyan). Top: Cells migrating parallel to the stretching direction. Bottom: Cells migrating perpendicular to the direction of stretching.

These results suggest that periodic stretching induces depolymerization of the stress fibers which are aligned parallel to the stretching direction, a phenomenon seen in slow-crawling cells.50,51

Blebbistatin-treated keratocytes migrate perpendicular to the direction of stretching

Inhibition of stress fiber depolymerization prevented any directional migration parallel to the stretching direction under periodic stretching stimuli (Figs. 2 and 3). The next question is whether the stress fiber-less keratocytes also migrate randomly.

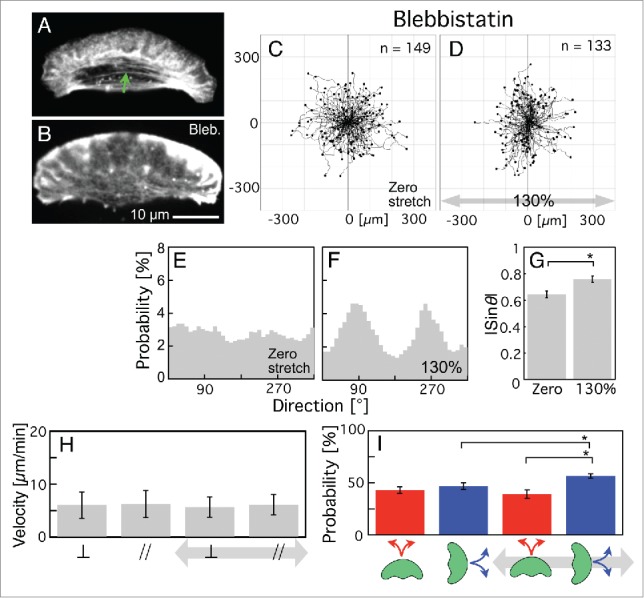

Stress fibers in keratocytes can be disassembled by treatment with low concentrations of blebbistatin,48,52 which is a myosin II ATPase inhibitor. To answer the above question, we treated keratocytes with 25 µM (±)-blebbistatin and applied periodic stretching stimuli. Typical keratocytes before and after the treatment with blebbistatin are shown in Figure 5A and B, respectively. The image brightness has been boosted to accentuate the stress fibers. They can be seen in the cell body only before the treatment (green arrow in Fig. 5A). The trajectories of cell migration subjected to zero stretching stimulus and those subjected to periodic stretching stimuli are shown in Figure 5C and D, respectively. Although the length of the trajectories was shortened by the inhibition of myosin II ATPase (compare Fig. 5C to Figs. 1A and 2A), the cells did in fact migrate. The probability of each direction of migration (θ) (Fig. 5E and F) was respectively calculated from Fig. 5C and D. Surprisingly, the cells tended to migrate perpendicular to the direction of stretching (90° or 270°) when subjected to periodic stretching (Fig. 5D, F and Movie S2), whereas they migrated randomly in its absence (Fig. 5C and E). The absolute value of the sine of the angle, |sin θ|, was calculated from Fig. 5C and D to provide an index of directional migration (Fig. 5G). The values for cells under periodic stretching stimuli (Fig. 5G, right) are significantly larger than those given zero stretching stimulus (Fig. 5G, left).

Figure 5.

Migration of blebbistatin-treated keratocytes on the elastic substratum given zero stretching stimulus or when subjected to periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio and 5-s time cycle for 30 min. (A and B) Distribution of stress fibers before (A) and after (B) treatment with blebbistatin. Actin filaments were stained with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin. The green arrow in A identifies a stress fiber. To be able to confirm the absence of stress fibers in B, the image brightness has been enhanced. (C and D) Trajectories given zero stretching stimulus (C, n = 149 from 9 experiments) and when subjected to periodic stretching (D, n = 133 from 6 experiments). Periodic stretching stimuli were applied parallel to the x-axis in D (gray arrow). (E and F) Probability of migration direction (θ) calculated from C and D, respectively. The angle (θ) was made by the x-axis and the vector from the initial location of a cell (t = 0 min) to the final location during the observation period (t = 30 min) (see Materials and methods for details). (G) The |sinθ| values calculated from C (left column) and D (right column), respectively. (H) Migration velocities on the elastic substratum, calculated from C and D. The two left-hand columns and 2 right-hand columns respectively represent velocities under zero stretching stimulus and under periodic stretching stimuli. The velocities perpendicular and parallel to the stretching direction are indicated as ⊥ and //, respectively. (I) Probability of a switch of migration direction on the elastic substratum calculated from C (2 left-hand columns) and D (2 right-hand columns). The red and blue columns respectively represent switching probabilities from perpendicular to parallel and vice versa. The bars in G and I, and H indicate SEM and SD, respectively. The p-values were calculated using Student's t-test. *p < 0.05.

This directional migration perpendicular to the stretching is identical to those of other fast-crawling cells such as intact HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells.23,33,34 The blebbistatin-treated keratocytes did not have stress fibers (Fig. 5B) as same as intact HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells. The origin of directional migration of intact HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells is not higher migration velocity in the direction perpendicular to the stretching direction but the higher probability of a switch of migration direction to perpendicular to the stretching direction.33 To test this, in the case of blebbistatin-treated keratocytes too, whether the origin was not a higher migration velocity perpendicular to the direction of stretching direction but, instead, a greater probability of a switch in migration direction to perpendicular to the stretching direction, we first compared the migration velocity perpendicular to the stretch direction and that parallel to it when given zero stretching stimulus and that under periodic stretching stimuli by analysis of the trajectories in Figure 5C and D at 120-s intervals. With zero stretching stimulus, there was no significant difference in the velocity between the perpendicular direction (left ⊥ column in Fig. 5H) and the parallel direction (left // column in Fig. 5H). When periodic stretching was applied (the 2 right-hand columns in Fig. 5H), the velocities changed in neither the perpendicular direction (compare the ⊥ columns in Fig. 5H) nor the parallel direction (compare the // columns in Fig. 5H). Thus, under periodic stretching, there was no significant difference in the velocity between in the perpendicular direction (right ⊥ in Fig. 5H) and in the parallel direction (right // in Fig. 5H).

Next, we calculated the probability of a switch of migration direction from perpendicular to parallel (the red columns in Fig. 5I) and that from parallel to perpendicular (the blue columns in Fig. 5I) at 120-s intervals from the trajectories of Fig. 5C and D. With zero stretching stimulus, there was no significant difference in the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel (left red column in Fig. 5I) or vice versa (left blue column in Fig. 5I). When periodic stretching was applied, the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel did not change (compare the red columns in Fig. 5I), although that from parallel to perpendicular significantly increased (compare the blue columns in Fig. 5I). As a result, when subjected to periodic stretching, the probability of a switch from parallel to perpendicular (right-hand blue column in Fig. 5I) was significantly higher than that perpendicular to parallel (right-hand red column in Fig. 5I). This suggests a switch of migration direction from parallel to perpendicular to the stretch direction to be the main cause of directional migration, as in the case of intact HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells.33

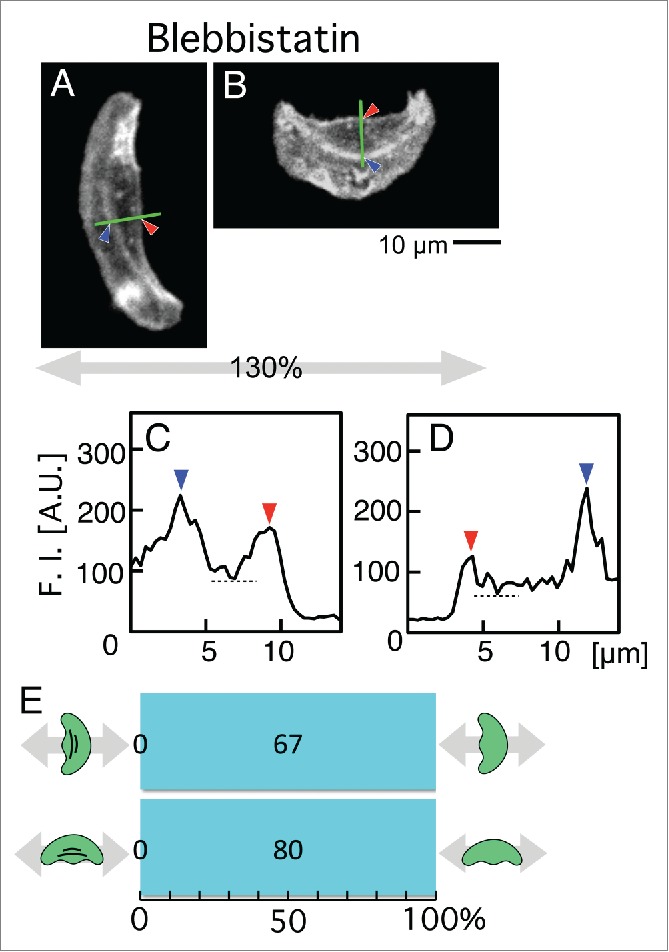

The presence or absence of stress fibers was also measured in the blebbistatin-treated keratocytes after periodic stretching. Figure 6A and B are typical cells migrating parallel and perpendicular to the direction of stretch, respectively. Fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin along the green lines in Figure 6A and B are shown in Figure 6C and D, respectively. Even when subjected to periodic stretching stimuli, cells never had their stress fibers regardless of the migration-direction (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Presence or absence of stress fibers in blebbistatin-treated keratocytes on the elastic substratum after periodic stretching with a 130% stretch ratio and 5-s time cycle for 30 min. The migration direction was determined in Figure 3A. (A and B) Distribution of stress fibers in typical cells migrating parallel (A) and perpendicular (B) to the direction of stretch. Actin filaments were stained with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin. Images A and B are typical of 67 and 80 cells, respectively. (C and D) Fluorescence intensity Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin along the green lines in A (C) and B (D), respectively. Cells with stress fibers were defined in the same manner as in Figure 3D and E. (E) Numbers of cells with stress fibers (magenta) and without (cyan). Top: Cells migrating parallel to the stretching direction. Bottom: Cells migrating perpendicular to the direction of stretching. In both cases, there was no cell with stress fiber.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to elucidate (I) how keratocytes migrate in response to periodic stretching of the substratum and (II) the principle of action within the cells. With respect to (I), our results showed that keratocytes have a unique bidirectional migration property, in which intact keratocytes migrate parallel to the stretching direction, whereas blebbistatin-treated keratocytes migrate perpendicular to it. Trajectory analysis revealed the principle of action that realizes bidirectional migration (II). Parallel migration of intact keratocytes seems be realized by the following 3 factors: (i) decreased migration velocity in the direction perpendicular to the stretch (compare the ⊥ columns in Fig. 1H), (ii) an increased probability of a switch of migration direction from perpendicular to parallel (compare the red columns in Fig. 1I), and (iii) decreased probability of a switch of migration direction from parallel to perpendicular (compare the blue columns in Fig. 1I). The (i) and (ii) can be considered to be the result of the depolymerization of stress fibers which had been aligned parallel to the stretching direction (Fig. 4C), because stress fibers play an important role in the stable migration of keratocytes.47 The cause of (iii) could not be determined in this study.

As the structure of the cells, keratocytes always migrate perpendicular to the orientation of the stress fibers in their cell body. Thus, the migration of intact keratocytes parallel to the stretching direction may be induced by the re-distribution of stress fibers, as seen in slow-crawling cells.26-32 In this study, we have shown only indirect and statistical evidence (Figs. 2–4), and could not completely rule out other possibilities. The decrease in velocity parallel to the stretching direction of jasplakinolide-treated cells (Fig. 2F) cannot be explained by the re-distribution of stress fibers in response to the periodic stretching stimuli. Keratocytes have a dense meshwork of thin actin filaments in their lamellipodium.46 Not only stress fibers but also actin filaments in the lamellipodium may respond to periodic stretching stimuli. In any case, the cytoskeleton is likely to be affected by the stretching and the relaxation via some form of molecular dynamics, such as the binding of cofilin to relaxed actin filaments50,51 which induces the depolymerization of the filaments or the opening of stretch-activated Ca2+ channels53 which induces the contraction of actomyosin. To reveal the connection of stress fibers to migration direction preference and what molecular dynamics is triggered by the repeated stretching of keratocytes, the application of repeated stretching to single live keratocytes will be required in future studies.

Perpendicular migration of blebbistatin-treated stress fiber-less keratocytes appears to be realized by a switch of migration direction from parallel to the stretch direction to perpendicular to the stretch direction (the blue columns in Fig. 5I). In a previous study,33 we showed that HL-60 cells and Dictyostelium cells migrate perpendicularly to the direction of stretch. This directional migration appears to be a strategy for survival adopted by fast-crawling cells, in which they migrate to avoid a direction they receive the force from the substratum. This behavior appears to improve their chances of escaping from a disturbance of the external environment over that of simply performing a random walk. Stress fiber-less keratocytes also may adopt the same strategy. However, the strategy of intact keratocytes is different: they migrate in the direction they receive the force from the substratum, paying no notice to other directions. This strategy matches the role of keratocytes on fish skin, which is to migrate directly to the wound and heal it.39 Because, during wound healing, keratocytes are connected each other and migrate as a sheet composed of multiple cells. In this situation, the rear cells seem to be pulled by the leading cells in the same way as in the repeated stretching of substratum.

The migration of blebbistatin-treated keratocytes perpendicular to the stretching direction seems to be induced by the disassembly of stress fibers (Figs. 5 and 6). However, inhibition of myosin II ATPase may also affect the direction of migration. The action in response to the periodic stretching (Figs. 5I) is exactly the same as that in fast-crawling HL-60 and Dictyostelium cells.33 Not only wild-type Dictyostelium cells but also cells expressing only ATPase-less myosin II showed perpendicular migration.34 Thus, if the reaction of blebbistatin-treated keratocytes is induced via the same molecular dynamics as Dictyostelium cells, myosin II ATPase should not be required for the perpendicular migration. Periodic stretching of the substratum induced myosin II localization equally at the edges of Dictyostelium cells, which travel perpendicular to the stretching direction.34 Future studies may reveal whether myosin II localization takes place in blebbistatin-treated keratocytes in response to stretching of the substratum.

The aim of this study was to identify the unique hybrid mechanosensing system in keratocytes and to elucidate the principle of action of the cell by means of trajectory analysis. In this paper, therefore, we did not address the molecular dynamics of the mechanosensing system. Further studies will no doubt add to our understanding of the integrated mechanosensing system of both types of crawling cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Primary cultures of fish epidermal keratocytes were prepared as described previously,47,49,54 with small modifications. Briefly, a goldfish, Carassius auratus, was anesthetized with Tricaine. Without sacrificing the fish, several scales were extracted using tweezers and washed in culture medium, which comprised DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The scales were placed external side up on the floor of a square chamber (18 × 18 mm and 2 mm in depth), the bottom of which was made of a 22 × 22 mm coverslip (No. 1, Matsunami, Osaka, Japan). They were then covered with another coverslip and allowed to adhere to the bottom coverslip for 1 h in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After removal of the upper coverslip, culture medium was added to the chamber and the scales were kept at 5% CO2 and 37 °C again overnight to allow the cells to spread from the scale. Cells were washed briefly with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (PBS– –) and then treated with 0.1% trypsin and 1 mM EDTA in PBS for 30 – 60 seconds. The trypsin was quenched with a 10-fold excess of culture medium.

Periodic stretching of the substratum

Periodic stretching of the substratum was performed as described previously,23,33,34 with small modifications. Briefly, elastic sheets with thick edge, 22 mm × 40 mm, were made from PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning Toray, Tokyo, Japan). The surface of the sheet was coated with collagen (Cellmatrix I-C, Nitta Gelatin, Osaka, Japan). The cells were transferred directly to the elastic sheets and allowed to recover for about 30 minutes. In all the experiments, time cycle, and duty ratio of stretching and relaxation were adjusted to 5 s and 1:1, respectively. Using elastic sheets, however, it is impossible to exclude Poisson's effect, the shrinkage in the direction perpendicular to the stretching, completely. In this study, when the sheet was stretched, perpendicular shrinkage was limited to ≤ 1/4 of the stretch by using the sheet with thick edge, as was the case in our previous study.23

Pharmacological treatments

The agents, (±)-blebbistatin (13186, Cayman, MI, USA) or jasplakinolide (11705, Cayman, MI, USA) were applied to the cells on the elastic sheets. Just after the application, the cells shrank. After about 15 – 30 minutes, the shape of the cells was restored and periodic stretching was started. All experiments were performed without removal of the reagents. Final concentrations of blebbistatin and jasplakinolide were 25 µM and 30 nM, respectively.

Statistical analysis of cell migration

The analysis was performed according to previously described methods.33 Briefly, from sequential images taken at 30-s intervals for 30 min, we measured the angle (θ; inset in Fig. 1C) made by the x-axis which was parallel to the stretching direction and the vector from the initial location of a cell (t = 0 min) to the final one during observation (t = 30 min) (thick arrow; inset in Fig. 1C) was measured. The location of the cell was determined as the center of the ventral surface of it. The absolute value of the sine of the angle, |sinθ|, was calculated to provide an index of directional migration. In preparing histograms for Figures 1, 2 and 5, the probability of migration direction was obtained by dividing the number in each direction by the total count number. In all histograms, the interior angle of each datum was set at 66.0°. This means that, for example, the value at 90° includes the number of cells that migrated in directions from 57° to 123°.

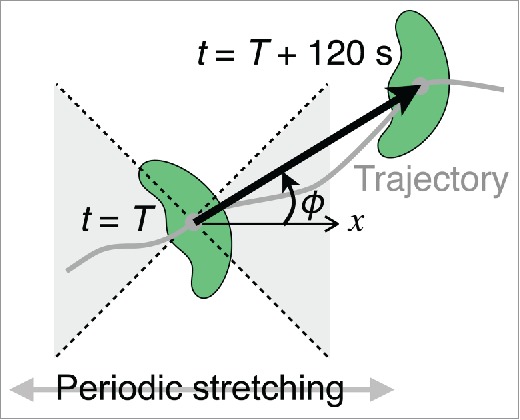

Migration velocities in the parallel and perpendicular directions, and the probabilities of a switch from parallel to perpendicular and vice versa, were estimated as follows. A vector from the initial location of a cell (t = T) to that in the time frame (t = T + 120 s) was defined (thick arrow in Fig. 7). When the angle (ϕ) between the x-axis (x in Fig. 7) and the vector was between 315 (–45) and 45° or between 135 and 225° (gray region in Fig. 7), the migration direction at t = T was labeled as “parallel” to the stretching direction, and when it was 45 – 135° or 225 – 315°, it was labeled as “perpendicular.” Average parallel and perpendicular velocities were individually calculated at 120-s intervals throughout the migration period of 30 min. The probability of a switch of migration direction from parallel to perpendicular was obtained by dividing the number of label changes from “parallel” to “perpendicular” by the total number of vectors throughout the 30-min migration period, and the probability of a switch from perpendicular to parallel was obtained by dividing the number of label changes from “perpendicular” to “parallel” by the total number of vectors during the 30-min migration period.

Figure 7.

Analysis methods for directional migration. A vector from the initial location of a cell (t = T) to that in the time frame (t = T + 120 s) was defined (thick arrow). When the angle (ϕ) between the x-axis (x) and the vector was between 315 (–45) and 45° or between 135 and 225° (gray region), the migration direction at t = T was labeled as “parallel” to the stretching direction, and when it was between 45 and 135° or between 225 and 315°, it was labeled as “perpendicular.” ϕ is regarded as the migration direction at each time point.

Filamentous actin staining

Filamentous actin staining was performed according to the methods described previously45 with small modifications. Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. The cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin (0.33 U/ml, A22283; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 60 min. The fixation and staining were all carried out at room temperature.

Microscopy

Fluorescence images of fixed cells were detected using an inverted microscope (Ti; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a laser confocal scanner unit (CSU-X1; Yokogawa, Tokyo, Japan) and an EM CCD camera (DU897; Andor, Belfast, UK) through a 100× objective lens (CFI Apo TIRF 100×H/1.49; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate

- fMLP

N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PDMS

polydimethylsiloxane

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Y. Sakumura (Aichi Pref. Univ.) for instruction on trajectory analysis.

Funding

YI was supported by MEXT Kakenhi Grants Nos. 26103524, 26650050 and 15H01323.

Author contributions

CO coordinated the research, and performed the experiments and data analysis. YI contributed to the analysis and discussion of the data. All authors wrote the manuscript.

References

- [1].Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell 1996; 84:359-69; PMID:8608589; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81280-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 2003; 302:1704-9; PMID:14657486; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1092053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol 2004; 265:23-32; PMID:14697350; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Reid B, Song B, McCaig CD, Zhao M. Wound healing in rat cornea: the role of electric currents. FASEB J 2005; 19:379-86; PMID:15746181; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1096/fj.04-2325com [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhao M, Song B, Pu J, Wada T, Reid B, Tai G, Wang F, Guo A, Walczysko P, Gu Y, et al.. Electrical signals control wound healing through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase-γ and PTEN. Nature 2006; 442:457-60; PMID:16871217; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Martin P. Wound healing–aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 1997; 276:75-81; PMID:9082989; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.276.5309.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parent CA. Making all the right moves: chemotaxis in neutrophils and Dictyostelium. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2004; 16:4-13; PMID:15037299; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Weninger W, Biro M, Jain R. Leukocyte migration in the interstitial space of non-lymphoid organs. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:232-46; PMID:24603165; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang MJ, Artemenko Y, Cai WJ, Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. The directional response of chemotactic cells depends on a balance between cytoskeletal architecture and the external gradient. Cell Rep 2014; 9:1110-21; PMID:25437564; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wu J, Pipathsouk A, Keizer-Gunnink A, Fusetti F, Alkema W, Liu S, Altschuler S, Wu L, Kortholt A, Weiner OD. Homer3 regulates the establishment of neutrophil polarity. Mol Biol Cell 2015; 26:1629-39; PMID:25739453; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nichols JM, Veltman D, Kay RR. Chemotaxis of a model organism: progress with Dictyostelium. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2015; 36:7-12; PMID:26183444; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ueda M, Sako Y, Tanaka T, Devreotes P, Yanagida T. Single-molecule analysis of chemotactic signaling in Dictyostelium cells. Science 2001; 294:864-7; PMID:11679673; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1063951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ueda M, Shibata T. Stochastic signal processing and transduction in chemotactic response of eukaryotic cells. Biophys J 2007; 93:11-20; PMID:17416630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1529/biophysj.106.100263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shin ME, He Y, Li D, Na S, Chowdhury F, Poh YC, Collin O, Su P, de Lanerolle P, Schwartz MA, et al.. Spatiotemporal organization, regulation, and functions of tractions during neutrophil chemotaxis. Blood 2010; 116:3297-310; PMID:20616216; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-12-260851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xu J, Wang F, Van Keymeulen A, Herzmark P, Straight A, Kelly K, Takuwa Y, Sugimoto N, Mitchison T, Bourne HR. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell 2003; 114:201-14; PMID:12887922; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00555-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shibata T, Nishikawa M, Matsuoka S, Ueda M. Intracellular encoding of spatiotemporal guidance cues in a self-organizing signaling system for chemotaxis in Dictyostelium cells. Biophys J 2013; 105:2199-209; PMID:24209866; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nishikawa M, Hörning M, Ueda M, Shibata T. Excitable signal transduction induces both spontaneous and directional cell asymmetries in the phosphatidylinositol lipid signaling system for eukaryotic chemotaxis. Biophys J 2014; 106:723-34; PMID:24507613; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Taniguchi D, Ishihara S, Oonuki T, Honda-Kitahara M, Kaneko K, Sawai S. Phase geometries of two-dimensional excitable waves govern self-organized morphodynamics of amoeboid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:5016-21; PMID:23479620; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1218025110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Giannone G, Sheetz MP. Substrate rigidity and force define form through tyrosine phosphatase and kinase pathways. Trends Cell Biol 2006; 16:213-23; PMID:16529933; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vogel V, Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006; 7:265-75; PMID:16607289; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Crosby LM, Luellen C, Zhang Z, Tague LL, Sinclair SE, Waters CM. Balance of life and death in alveolar epithelial type II cells: proliferation, apoptosis, and the effects of cyclic stretch on wound healing. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2011; 301:L536-46; PMID:21724858; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajplung.00371.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Desai LP, White SR, Waters CM. Cyclic mechanical stretch decreases cell migration by inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- and focal adhesion kinase-mediated JNK1 activation. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:4511-9; PMID:20018857; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.084335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Iwadate Y, Yumura S. Cyclic stretch of the substratum using a shape-memory alloy induces directional migration in Dictyostelium cells. BioTechniques 2009; 47:757-67; PMID:19852761; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2144/000113217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Naruse K, Yamada T, Sai XR, Hamaguchi M, Sokabe M. Pp125FAK is required for stretch dependent morphological response of endothelial cells. Oncogene 1998; 17:455-63; PMID:9696039; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1201950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Naruse K, Yamada T, Sokabe M. Involvement of SA channels in orienting response of cultured endothelial cells to cyclic stretch. Am J Physiol - Heart Circ Physiol 1998; 274:H1532-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Birukov KG, Jacobson JR, Flores AA, Ye SQ, Birukova AA, Verin AD, Garcia JGN. Magnitude-dependent regulation of pulmonary endothelial cell barrier function by cyclic stretch. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003; 285:L785-97; PMID:12639843; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajplung.00336.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kaunas R, Nguyen P, Usami S, Chien S. Cooperative effects of Rho and mechanical stretch on stress fiber organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:15895-900; PMID:16247009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0506041102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tondon A, Hsu HJ, Kaunas R. Dependence of cyclic stretch-induced stress fiber reorientation on stretch waveform. J Biomech 2011; 45:728-35; PMID:22206828; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lee CF, Haase C, Deguchi S, Kaunas R. Cyclic stretch-induced stress fiber dynamics - dependence on strain rate, Rho-kinase and MLCK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010; 401:344-9; PMID:20849825; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhao L, Sang C, Yang C, Zhuang F. Effects of stress fiber contractility on uniaxial stretch guiding mitosis orientation and stress fiber alignment. J Biomech 2011; 44:2388-94; PMID:21767844; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sato K, Adachi T, Matsuo M, Tomita Y. Quantitative evaluation of threshold fiber strain that induces reorganization of cytoskeletal actin fiber structure in osteoblastic cells. J Biomech 2005; 38:1895-901; PMID:16023478; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Morioka M, Parameswaran H, Naruse K, Kondo M, Sokabe M, Hasegawa Y, Suki B, Ito S. Microtubule dynamics regulate cyclic stretch-induced cell alignment in human airway smooth muscle cells. PLoS One 2011; 6:e26384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Okimura C, Ueda K, Sakumura Y, Iwadate Y. Fast-crawling cell types migrate to avoid the direction of periodic substratum stretching. Cell Adhes Migr in press; 2016; PMID:1170268; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/19336918.2016.1170268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Iwadate Y, Okimura C, Sato K, Nakashima Y, Tsujioka M, Minami K. Myosin-II-mediated directional migration of Dictyostelium cells in response to cyclic stretching of substratum. Biophys J 2013; 104:748-58; PMID:23442953; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li L, Nørrelykke SF, Cox EC. Persistent cell motion in the absence of external signals: a search strategy for eukaryotic cells. PLoS One 2008; 3:e2093; PMID:18461173; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0002093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yang TD, Park JS, Choi Y, Choi W, Ko TW, Lee KJ. Zigzag turning preference of freely crawling cells. PloS One 2011; 6:e20255; PMID:21687729; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0020255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Takagi H, Sato MJ, Yanagida T, Ueda M. Functional analysis of spontaneous cell movement under different physiological conditions. PLoS One 2008; 3:e2648; PMID:18612377; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0002648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Goodrich HB. Cell Behavior in Tissue Cultures. Biol Bull 1924; 46:252-62; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2307/1536726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Morita T, Tsuchiya A, Sugimoto M. Myosin II activity is required for functional leading-edge cells and closure of epidermal sheets in fish skin ex vivo. Cell Tissue Res 2011; 345:379-90; PMID:21847608; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00441-011-1219-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ream RA, Theriot JA, Somero GN. Influences of thermal acclimation and acute temperature change on the motility of epithelial wound-healing cells (keratocytes) of tropical, temperate and Antarctic fish. J Exp Biol 2003; 206:4539-51; PMID:14610038; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jeb.00706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Euteneuer U, Schliwa M. Persistent, directional motility of cells and cytoplasmic fragments in the absence of microtubules. Nature 1984; 310:58-61; PMID:6377086; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/310058a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lee J, Ishihara A, Theriot JA, Jacobson K. Principles of locomotion for simple-shaped cells. Nature 1993; 362:167-71; PMID:8450887; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/362167a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Verkhovsky AB, Svitkina TM, Borisy GG. Self-polarization and directional motility of cytoplasm. Curr Biol 1999; 9:11-20; PMID:9889119; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80042-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Keren K, Pincus Z, Allen GM, Barnhart EL, Marriott G, Mogilner A, Theriot JA. Mechanism of shape determination in motile cells. Nature 2008; 453:475-80; PMID:18497816; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Barnhart EL, Lee KC, Keren K, Mogilner A, Theriot JA. An adhesion-dependent switch between mechanisms that determine motile cell shape. PLoS Biol 2011; 9:e1001059; PMID:21559321; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Svitkina TM, Verkhovsky AB, McQuade KM, Borisy GG. Analysis of the actin-myosin II system in fish epidermal keratocytes: mechanism of cell body translocation. J Cell Biol 1997; 139:397-415; PMID:9334344; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.139.2.397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Nakata T, Okimura C, Mizuno T, Iwadate Y. The role of stress fibers in the shape determination mechanism of fish keratocytes. Biophys J 2016; 110:481-92; PMID:26789770; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sonoda A, Okimura C, Iwadate Y. Shape and area of keratocytes are related to the distribution and magnitude of their traction forces. Cell Struct Funct 2016; 41:33-43; PMID:26754329; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1247/csf.15008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nakashima H, Okimura C, Iwadate Y. The molecular dynamics of crawling migration in microtubule-disrupted keratocytes. Biophys Physicobiol 2015; 12:21-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2142/biophysico.12.0_21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hayakawa K, Tatsumi H, Sokabe M. Actin filaments function as a tension sensor by tension-dependent binding of cofilin to the filament. J Cell Biol 2011; 195:721-7; PMID:22123860; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201102039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hayakawa K, Sakakibara S, Sokabe M, Tatsumi H. Single-molecule imaging and kinetic analysis of cooperative cofilin-actin filament interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:9810-5; PMID:24958883; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1321451111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Okeyo KO, Adachi T, Sunaga J, Hojo M. Actomyosin contractility spatiotemporally regulates actin network dynamics in migrating cells. J Biomech 2009; 42:2540-8; PMID:19665125; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lee J, Ishihara A, Oxford G, Johnson B, Jacobson K. Regulation of cell movement is mediated by stretch-activated calcium channels. Nature 1999; 400:382-6; PMID:10432119; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/22578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tsugiyama H, Okimura C, Mizuno T, Iwadate Y. Electroporation of adherent cells with low sample volumes on a microscope stage. J Exp Biol 2013; 216:3591-8; PMID:23788710; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jeb.089870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.