Abstract

Infants with intestinal failure who are parenteral nutrition (PN)-dependent may develop cholestatic liver injury and cirrhosis (PN-associated liver injury: PNALI). The pathogenesis of PNALI remains incompletely understood. We hypothesized that intestinal injury with increased intestinal permeability combined with administration of PN promotes LPS-TLR4 signaling dependent Kupffer cell activation as an early event in the pathogenesis of PNALI. We developed a mouse model in which intestinal injury and increased permeability were induced by oral treatment for 4 days with dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) followed by continuous infusion of soy lipid-based PN solution through a central venous catheter for 7 (PN/DSS7d) and 28 (PN/DSS28d) days. Liver injury and cholestasis were evaluated by serum AST, ALT, bile acids, total bilirubin, and by histology. Purified Kupffer cells were probed for transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines. PN/DSS7d mice showed elevated portal vein LPS levels, evidence of hepatocyte injury and cholestasis, and increased Kupffer cell expression of IL6, TNFα, and TGFβ. Serological markers of liver injury remained elevated in PN/DSS28d mice associated with focal inflammation, hepatocyte apoptosis, peliosis, and Kupffer cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia. PN infusion without DSS pre-treatment or DSS pre-treatment alone did not result in liver injury or Kupffer cell activation. Suppression of the intestinal microbiota with broad spectrum antibiotics or ablation of TLR4 signaling in TLR4 mutant mice resulted in significantly reduced Kupffer cell activation and markedly attenuated liver injury in PN/DSS7d mice.

Conclusion

These data suggest that intestinal-derived LPS activates Kupffer cells through TLR4 signaling in early stages of PNALI.

Keywords: microbiota, short bowel syndrome, cytokines, cholestasis, macrophage

Since its first clinical use in the 1960’s, parenteral nutrition (PN) has significantly improved the survival of infants who are unable to tolerate enteral feedings, especially those with intestinal failure caused by necrotizing enterocolitis, short bowel syndrome, intestinal atresias, or other gastrointestinal malformations (1). However, a significant complication in PN-infused infants is the development of cholestatic liver injury (PN associated liver injury, or PNALI) that can rapidly progress to cirrhosis in those that fail to be weaned off PN (2). Multi-visceral transplantation then becomes necessary for survival in many of these infants (3). To date, the pathogenesis of PNALI remains poorly understood which has been a critical barrier for the design of more effective treatment and prevention methods. One of the major obstacles to advances in this field has been the lack of an animal model that allows investigation of the early events that trigger liver injury. The readily available spectrum of transgenic mice makes a mouse model of PNALI highly desirable in order to study cellular, molecular, and immunological mechanisms that may initiate liver injury.

The clinical observation that severity and chronicity of PNALI are increased in those PN dependent infants that have concomitant underlying intestinal inflammation (4) may provide important clues for making inroads to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of PNALI. For example, the lack of enteral feedings in PN infused infants may significantly reduce intestinal motility favoring bacterial overgrowth (4–6), alterations in mucosal immunity and subsequent aggravation of underlying inflammation (6). In addition, the remaining intestine after surgical resection may lack the barrier function of the ileal-cecal valve, be inflamed by the underlying disease process (e.g., necrotizing enterocolitis), nonspecific inflammation (e.g. jejunitis and short gut colitis (7), or may have disturbed vascular perfusion. The combination of these factors together with the presumed a priori increased intestinal permeability of infants (8) may result in a significant compromise of the intestinal barrier function (9). As a result, gut derived toll like receptor (TLR) agonists such as bacterial proteins, lipids or nucleic acids may be absorbed into the portal circulation in large amounts. Activation of TLR signaling in Kupffer cells may subsequently initiate hepatic inflammatory pathways that promote hepatocyte injury, cholestasis, apoptosis and necrosis, as well as activation of stellate cells (10). Intriguingly, Kupffer cell hyperplasia and inflammation are characteristic of the liver histopathology in human infants with PNALI (11). Recent work in mouse models investigating the pathogenesis of cholestatic (12), alcoholic (13), and non-alcoholic (14) liver injury has implied a dysfunctional intestinal barrier, increased absorption of gut derived TLR agonists, specifically lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and subsequent TLR dependent activation of Kupffer cells as disease initiating and promoting mechanisms (referred to as the gut-liver axis).

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that intestinal injury with increased intestinal permeability combined with administration of PN promotes TLR dependent Kupffer cell activation as an early event in the pathogenesis of PNALI. In order to test this hypothesis we designed a mouse model that specifically replicates the initial events that occur in human infants at greatest risk for the development of PNALI, namely the combination of PN infusion and intestinal injury/increased intestinal permeability. Using this mouse model we investigated the role of Kupffer cell activation by the intestinal microbiota through TLR4 signaling during the early stages of liver injury in PNALI.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mouse model

C57BL/6 wild type and syngeneic TLR4 mutant (B6.B10ScN-Tlr4lps-del/JthJ(15)) adult male mice (8–10 weeks old; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were exposed ad lib to 2.5% dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) in the drinking water for 4 days. Mice then received regular drinking water for 24 hrs (referred to as “DSS pre-treatment”) before surgical placement of a central venous catheter (CVC) (Silastic tubing, 0.012 inches internal diameter; Dow Corning, USA) under pentobarbital anesthesia into the right jugular vein. The proximal end of the CVC was tunneled subcutaneously and exited between the shoulder plates. Mice were then placed in a rubber harness (Instech Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and the CVC was connected to an infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Mice were recovered from surgery for 24hrs with i.v. normal saline (NS) infusion (to prevent thrombosis around the CVC) at a rate of 0.23 ml/hr and given ad lib access to chow and water. After 24 hrs mice were continuously infused for 7 or 28 days with PN (“PN/DSS7d” and “PN/DSS28d”) at a rate of 0.29 ml/hr providing a caloric intake of 8.4 Kcal/24 hrs (Table 1). All PN infused mice had access to water ad lib but not to chow during the PN infusion period. Several control groups of mice were also studied. DSS pre-treated mice were infused with NS for 7 days instead of PN (“NS/DSS”). DSS pre-treated mice that did not have a CVC placed were given free access to chow and water for either 1 day (DSS mice) or 8 days (DSS+ 8d chow). Other mice were not DSS pre-treated but underwent CVC placement and received PN or NS, respectively, in the same manner as PN/DSS and NS/DSS mice (“PN” and “NS”). Un-manipulated control mice (“chow fed controls”) had free access to chow and water without being connected to harness-swivel system for a period of 12 days. All mice were individually housed in metabolic cages. DSS pre-treatment did not cause weight loss; however mice lost a mean of 0.27 to 1.45 grams during the 7-day period PN administration (Table 2). Blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus under pentobarbital anesthesia. Serum was analyzed by the University of Colorado Hospital Clinical Chemistry Laboratory for aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and total bilirubin levels. Total serum bile acids (TSBA) were analyzed using a total bile acid detection kit (Diazyme Laboratories, Poway, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All animals were treated humanely and all animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Table 1.

Composition of the PN solution used in the PNALI mouse model.

| Parenteral Nutrition Solution Components used in experiments per 100ml | |

|---|---|

| Aminosyn 15% [ABBOTT] | 26.7ml; 4g |

| Dextrose | 36ml; 25.5g |

| Lipid | 10ml; 2g |

| Sodium phosphate | 1.34mmol |

| Potassium chloride | 1.6mEq |

| Sodium chloride | 3.2mEq |

| Potassuim acetate | 12mEq |

| Magnesium sulphate | 0.8mEq |

| Calcium gluconate | 1.32mEq |

| Multitrace-5 concentrate (MTE-5) | 0.1ml |

| Heparin | 500units |

| Nitrogen content | 0.61g |

| Non-protein calories | 105.68 Kcal |

| Protein calories | 16.02 Kcal |

| Dextrose calories | 85.68 Kcal |

| Lipid calories | 20.00 Kcal |

| Total calories | 121.7 Kcal |

| Multi Vitamins (MVI) | 2ml |

MTE-5 contains: zinc, copper manganese, chromium, and selenium

Table 2.

Weight change according to treatment.

| Group | DSS pre-treatment | PN or NS infusion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 4 | Δ (gm) | p | Day 5 | Day 12 or 33# | Δ(gm) | p | |

| NS/DSS (n=27) | 22.17 (± 0.34) | 22.67 (± 0.37) | +0.50 | n.s. | 22.30 (± 0.29) | 23.30 (± 0.27) | +1.00 | <0.05 |

| PN7d/DSS (n=30) | 22.87 (± 0.36) | 22.93 (± 0.30) | +0.06 | n.s. | 22.09 (± 0.21) | 20.64 (± 0.30) | −1.45 | <0.05 |

| #PN28d/DSS (n=5) | 23.06 (± 0.40) | 23.80 (± 0.37) | +0.74 | n.s. | 23.80 (± 0.37) | 21.20 (± 0.45) | −2.60 | <0.05 |

| PN7d/DSS+Abx (n=11) | 22.55 (± 0.45) | 22.73 (± 0.38) | +0.18 | n.s. | 22.45 (± 0.37) | 22.18 (± 0.46) | −0.27 | <0.05 |

| PN7d/DSStlr4mut (n=7) | 22.00 (± 0.71) | 22.20 (± 0.86) | +0.20 | n.s. | 21.60 (± 1.20) | 20.40 (± 0.87) | −1.20 | <0.05 |

| PN (n=12) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 23.42 (± 0.65) | 22.08 (± 0.35) | −1.34 | <0.05 |

| NS (n=12) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 21.33 (± 0.41) | 22.00 (± 0.40) | +0.67 | <0.05 |

| Chow fed (n=12) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 23.33 (± 0.33) | 24.67 (± 0.33) | +1.34 | <0.05 |

Mice were weighed and DSS pre-treatment was initiated on day 0. DSS was removed from drinking water on day 4 and mice were weighed again. On day 5 mice were weighed again, underwent central venous catheter placement and were infused with NS for 24hrs. On day 6 PN or NS infusion was initiated for 7 days through day 12 or for 28 days through day 33. P values compare day 0 vs. day 4 and day 5 vs. day 12 or 33 by t-test. Values presented are mean ± SEM of body weight in grams (gm). Note that DSS pre-treatment did not result in significant weight loss. Note that PN administration was associated with a loss of 1.34 (PN) to 1.43 (PN7d/DSS) and 2.60 (PN28d/DSS) grams of body weight, respectively. Weight loss in PN/DSS treated TLR4 mutant mice was similar to weight loss in PN/DSS treated wild type mice. Treatment PN/DSS mice oral with antibiotics of resulted in reduced but still significant weight loss (−0.27gm). DSS = Dextran sulphate sodium; PN = parenteral nutrition; NS = normal saline; Δ change in body weight in grams (gm). n/a (not applicable) for groups of mice that were not DSS pre-treated. n.s. (not significant) as determined by p>0.05.

Intestinal permeability and portal vein LPS measurements

Intestinal permeability was examined by oral gavage with 200µl FITC-dextran (4,000 kD at 80 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) on the day of sacrifice. Four hours after gavage, mice were anesthetized with i.p. pentobarbital and blood was drawn from the portal vein (400µl). Serum was prepared and analyzed for fluorescence measured at excitation wavelength of 494nm and emission wavelength of 518 nm. LPS was measured in serum obtained from the portal vein using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysis Endpoint Assay (Lonza; Williamsport, PA) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Suppression of Intestinal Microbiota

A group of PN/DSS7d mice was exposed ad lib to an oral cocktail of four broad spectrum antibiotics provided in the drinking water during the entire course of the 7-day PN infusion (referred to as “PN/DSS+Abx” mice). The antibiotics, mixed fresh every 24 hrs, included vancomycin (1g/l), streptomycin (2g/l), ampicillin (2g/l), and metronidazole (2g/l), based on the protocol of Fagarasan et al. (16).

Bacterial load assay

Fecal samples were obtained from the descending colon on the day of sacrifice using sterile technique and snap frozen and stored at −70°. Total DNA was extracted and bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA was PCR amplified using specific primers as described (17). Total bacterial ribosomal DNA gene copy numbers were measured in triplicate using the assay developed by Nadkarni (18) and copies per ng template DNA were calculated.

Kupffer cell and splenic macrophage purification

Pooled livers (4–6 mice) were minced in cold Hanks buffer (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and incubated in LiberaseR (Hoffman La Roche, Germany) and DNAse (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at 37°C followed by low speed centrifugation at 25g and further separation over a 16% Histodenz gradient at 1500g for 20 minutes. CD11b positive cells (referred to as Kupffer cells in this study) were then purified using positive selection with magnetic CD11b antibody beads and magnetic columns (MACS, Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). FACS-Calibur analysis demonstrated >95% purity after labeling purified cells with CD11b-PE antibody (Miltenyi; Auburn, CA). Spleens were pooled (n=3 each) from of NS/DSS, PN/DSS7d, and chow fed controls, minced in ice cold Hanks buffer, centrifuged at 200g for 5 minutes followed by red cell lysis and subsequent positive selection (referred to as splenic macrophages in this study) using CD11b beads as described above.

RNA isolation and quantitative gene expression analysis

RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), DNAse treated (Ambion, Austin, TX) and reverse transcribed with iScript (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Gene expression was analyzed in triplicate by qRT-PCR analysis on an Applied Biosystems 7300 cycler using commercially available mouse TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems). Data are expressed as normalized gene expression relative to untreated chow fed control or NS/DSS treated mice using the Δ/Δ Ct method. RNA was extracted, prepared, and analyzed from whole liver tissue as above.

Histological analysis

Liver tissue, terminal ileum, and colon were removed at sacrifice, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded and prepared for histological slides. Slides were stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E), Masson’s Trichrome and Sirius Red according to standard staining protocols. Slides were examined by two pediatric pathologists (MF and ML) blinded to treatment groups. Kupffer cells and activated neutrophils were visualized using antibodies specific for F4/80 (clone BM8; BMA Biomedicals, Switzerland) and myeloperoxidase (MPO; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) using standard immunohistochemistry protocols.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons were used to determine statistical significance when more than two groups of mice were compared. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

DSS pre-treatment induces intestinal inflammation and increased intestinal permeability

We first determined if the DSS pre-treatment protocol, which uses a relatively short DSS treatment time (i.e. 4 days) and low DSS dose (2.5%) as compared to other DSS protocols (19), would induce intestinal inflammation and increased permeability without concomitant liver injury and Kupffer cell activation. DSS pre-treatment uniformly led to small amounts of visible blood in the fecal pellets starting on day 4 of DSS which persisted for an additional 2–3 days, providing clinical evidence of intestinal inflammation. Histological analysis of H&E stains and Immunostains of terminal ileum and colon obtained after DSS pre-treatment revealed focal infiltrates of F4/80 positive macrophages and activated MPO positive neutrophils (not shown) in the colon, consistent with mild colitis. Intestinal permeability was assessed in DSS mice (n=10) and PN/DSS7d mice (n=6) and compared to chow fed control mice for absorption of FITC dextran into the portal blood. Untreated chow fed control mice that were not gavaged with FITC dextran (n=8) had virtually no serum fluorescence. DSS mice gavaged with FITC dextran had 8-fold higher (p< 0.05) fluorescence in portal blood serum compared to FITC dextran gavaged chow fed control mice (n=5). Fluorescence in portal blood from PN/DSS7d mice was also 8-fold increased compared to chow fed control mice (p<0.05) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Increased intestinal permeability combined with PN infusion in mice induces liver injury and cholestasis.

(A) DSS pre-treated (n=10), PN/DSS7d (n=6), and untreated control mice (chow; n=5) were gavaged with FITC labeled-dextran to determine intestinal permeability. Untreated control mice not gavaged with FITC labeled-dextran are shown as a base line control (n=8). 4hrs later fluorescence was measured in portal serum specimens. Intestinal permeability was increased after DSS pre-treatment (DSS) and remained elevated after PN/DSS7d treatment. *p<0.05 DSS and PN/DSS7d vs. chow; determined by One-Way ANOVA. (B) Increased absorption of LPS in mice with increased intestinal permeability. Portal serum LPS levels [EU/L] were measured in untreated chow fed controls (n=8), DSS pre-treated (n=8), DSS+8d chow (n=8), and PN/DSS7d mice (n=6). DSS treatment increased LPS absorption, which was further significantly increased in PN/DSS mice compared to the other groups; *p<0.05 by One-Way ANOVA. (C–F) The combination of PN infusion with increased intestinal permeability induced hepatocyte injury (C,D) and cholestasis (E,F) in mice after 7 and 28 days of PN; *p<0.05 PN/DSS vs. controls by One-Way ANOVA. Mean values and standard error of mean are depicted.

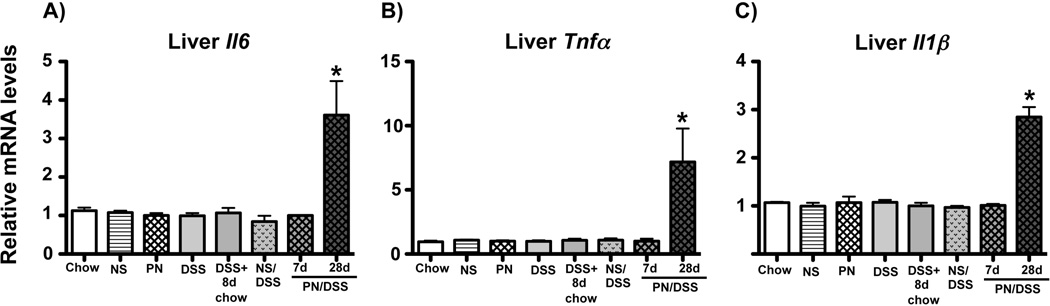

We next determined if increased intestinal permeability was associated with absorption of LPS into the portal venous circulation. LPS levels in portal blood were significantly increased (two-fold) in DSS mice (n=8) compared to untreated chow fed control mice (n=8) with further increases in DSS+8d chow mice (n=8). PN/DSS7d treatment (n=6) was associated with even higher levels of portal blood LPS compared to DSS+8d chow mice (p<0.05) (Figure 1B). These data indicate that administration of PN combined with underlying intestinal injury promotes persistently increased intestinal permeability and significant absorption of LPS into the portal circulation. We next tested if DSS pre-treatment induced liver injury. DSS (n=9) and DSS+8d chow mice (n=6) did not show elevations of AST, ALT, TSBA, or bilirubin levels compared to untreated chow fed control mice (n=20) (Figure 1C–F). RNA expression analysis in whole liver homogenate (n=5 each) and isolated Kupffer cells (pooled from 4–6 mice) showed no increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL6, IL1β, and TNFα in DSS, DSS+8d chow, and NS/DSS mice relative to chow fed control mice (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Furthermore, histology of livers obtained from DSS mice, DSS+8d chow mice, and NS/DSS mice showed no inflammation, cholestasis, steatosis, fibrosis or hepatocyte death, and immunostaining using F4/80 revealed normal appearance and numbers of Kupffer cells (not shown).

Figure 3. Kupffer cell activation in PN/DSS mice.

(A–C) qRT-PCR analysis depicting relative transcript levels of IL6 (A), TNFα (B), and TGFβ (C) mRNA in purified Kupffer cells. Kupffer cells derived from LPS injected mice (LPS) served as a positive control for innate activation of Kupffer cells. Kupffer cell activation is increased in PN/DSS7d wild type mice (PN/DSS7d tlr4wt) compared to controls. Note that DSS treatment alone (DSS, DSS+8d chow, NS/DSS) or PN infusion in the absence of DSS pre-treatment (PN) does not induce Kupffer cell activation. Kupffer cell activation is attenuated after suppression of bowel flora (PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx) or ablation of TLR4 signaling (PN/DSS7d tlr4mut) compared to Kupffer cells from PN/DSS7d wild type mice (PN/DSS7d tlr4wt). Data were normalized to Hypoxanthine-phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (Hprt1) as endogenous control gene. mRNA levels are expressed relative to results obtained from untreated chow fed controls. Mean values and standard error of mean (SEM) of two independent Kupffer cell isolations that were analyzed in triplicate are depicted. *p<0.05 PN/DSS7d tlr4wt and LPS vs. controls; #p<0.05 PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx and PN/DSS7d tlr4mut vs. PN/DSS7d tlr4wt; determined by One-Way ANOVA.

Figure 4. Inflammatory gene transcription is increased in livers from PN/DSS28d mice.

qRT-PCR analysis depicting relative transcript levels of IL6 (A), TNFα (B), and IL1β (C) mRNA in whole liver homogenates. Elevated transcription was present at 28 but not 7 days of PN/DSS. Data were normalized to Hypoxanthine-phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (Hprt1) as endogenous control gene. mRNA levels are expressed relative to results obtained from untreated chow fed controls. Mean values and SEM from n=5 samples tested in triplicate are depicted. *p<0.05 PN/DSS28d vs. all other groups; determined by One-Way ANOVA.

PN infusion combined with increased intestinal permeability induces liver injury

We next sought to determine if combining PN infusion with increased intestinal permeability would induce liver injury. For this purpose we randomized DSS pre-treated mice into two groups that were either infused with PN (PN/DSS7d mice; n=30) or NS (NS/DSS7d mice: n=20) for 7 days. PN/DSS7d treatment resulted in significantly elevated AST (~4 fold; p=0.0006), ALT (~4 fold; p=0.0008), TSBA (>10 fold; p=0.0037), and total bilirubin (~2 fold; p=0.0137) levels compared to NS/DSS, DSS (n=9), DSS+8d chow (n=6), and untreated chow fed control mice (n=20) (Figure 1C–F). We next tested if infusion with PN by itself (i.e. in the absence of intestinal injury) would promote liver injury. PN infusion for 7 days by itself did not cause significant liver injury as measured by AST, ALT, and bilirubin levels in PN mice (n=10) compared to NS (n=12) or untreated chow fed control mice (n=20; p>0.05) (Figure 1C–E); mildly elevated TSBA levels were observed in PN mice compared to NS and untreated chow fed control mice (p<0.05) (Figure 1F). Thus, PN in combination with DSS, but not DSS or PN alone, led to significant liver injury within 7 days. Histology of H&E, Trichrome and Sirius red stained livers did not show significant alterations in PN/DSS7d mice compared to NS/DSS and chow controls (data not shown). The relatively normal liver histology in PN/DSS7d mice is consistent with this model representing an early phase of liver injury.

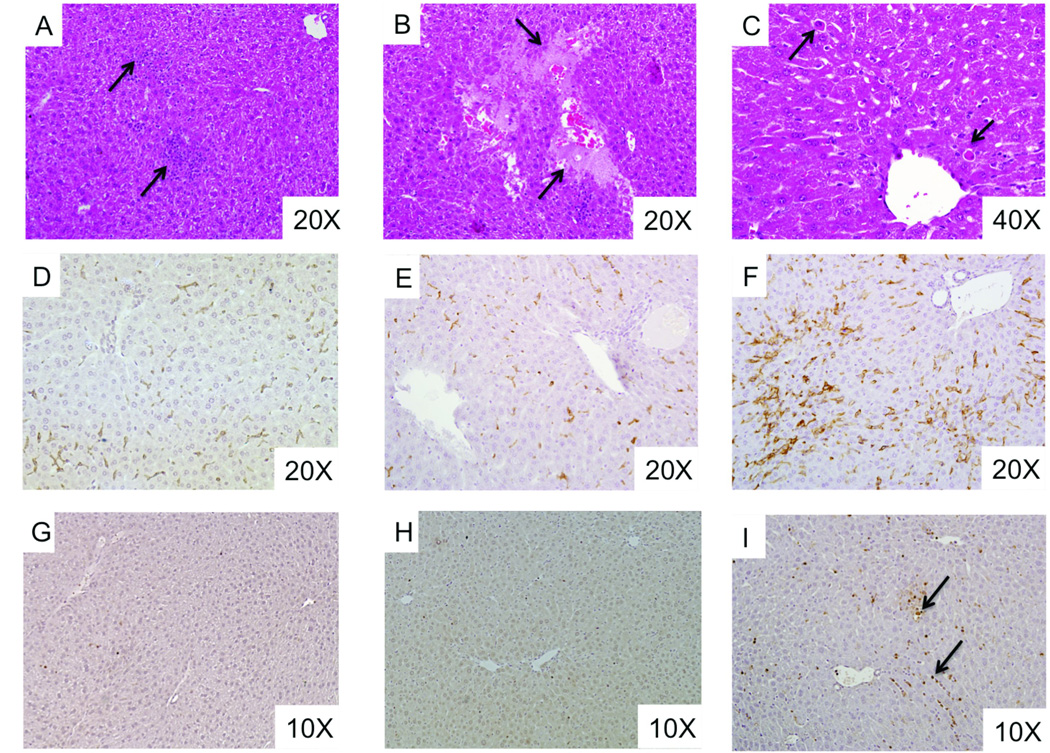

We next determined the effect of longer PN infusion in DSS pre-treated mice. Infusion of PN in DSS pre-treated mice was carried out for 28 days (PN/DSS 28d mice; n=5). AST, TSBA, and bilirubin levels remained elevated and were comparable to those in PN/DSS7d mice (n=30) while ALT levels were even further increased after 28 days of PN (Figure 1C–F). Liver histology at 28 days showed focal areas of mixed inflammation in the parenchyma, hepatocyte apoptosis (Councilman bodies), loss of hepatocytes (i.e. peliosis), and Kupffer cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy, suggestive of Kupffer cell activation (Figure 2). There was no evidence of steatosis, bile duct injury or portal fibrosis.

Figure 2. PN/DSS treatment induces histological liver lesions.

(A–C) H&E stained liver from PN/DSS28d mice shows focal areas of inflammation (arrows in panel A), loss of hepatocytes (arrows in panel B) and focal hepatocellular apoptosis (arrows in panel C pointing to Councilman bodies). (D–F) Immunohistochemistry using pan macrophage marker F4/80 demonstrates Kupffer cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy (arrow in panel F) in PN/DSS28d mice (F) as compared to PN/DSS7d mice (E) and chow fed control mice (D).

PN/DSS treatment is associated with activation of Kupffer cells

We next tested if liver injury in PN/DSS7d mice was associated with activation of Kupffer cells. Kupffer cells were purified from pooled livers (4–6 mice each) derived from wild type PN/DSS7d (PN/DSS7d tlr4wt), NS/DSS, and untreated chow control mice. Due to limited amounts of RNA obtained from purified Kupffer cells we focused our gene expression analysis on canonical cytokines downstream of TLR signaling, i.e. expression of IL6, TNFα and TGFβ. As a positive control for TLR activated Kupffer cell gene expression, Kupffer cells were purified from livers of mice that received i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg LPS (from E. coli serotype O111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 16 hrs prior to sacrifice. Transcription of IL6 (2.5 fold), TNFα (2 fold) and TGFβ (40 fold) was significantly (p<0.05) up-regulated in Kupffer cells derived from PN/DSS7d tlr4wt mice compared to cells from NS/DSS and chow control mice (p<0.05), and was comparable to that detected in Kupffer cells from LPS injected mice (Figure 3A–C). Kupffer cells purified from pooled livers of PN or DSS mice had expression levels of IL6, TNFα and TGFβ similar to Kupffer cells from NS and chow fed control mice (Figure 3A–C), indicating that neither PN nor DSS treatment alone promoted Kupffer cell activation. Importantly, transcriptional analysis of purified CD11b positive splenic macrophages isolated from PN/DSS7d mice (n=3) did not reveal increased cytokine transcription for IL6, TNFα and TGFβ compared to NS/DSS controls (n=3) (data not shown). Furthermore, transcript levels of IL6, IL1β, and TNFα (Figure 4A–C) were not elevated in RNA from whole liver homogenate from PN/DSS7d mice (n=10) compared to NS/DSS (n=5), DSS (n=5), NS (n=5), PN (n=5), and chow mice (n=5), but were elevated in PN/DSS28d mice (n=5). These data indicate that activation of Kupffer cells is an early event in PNALI.

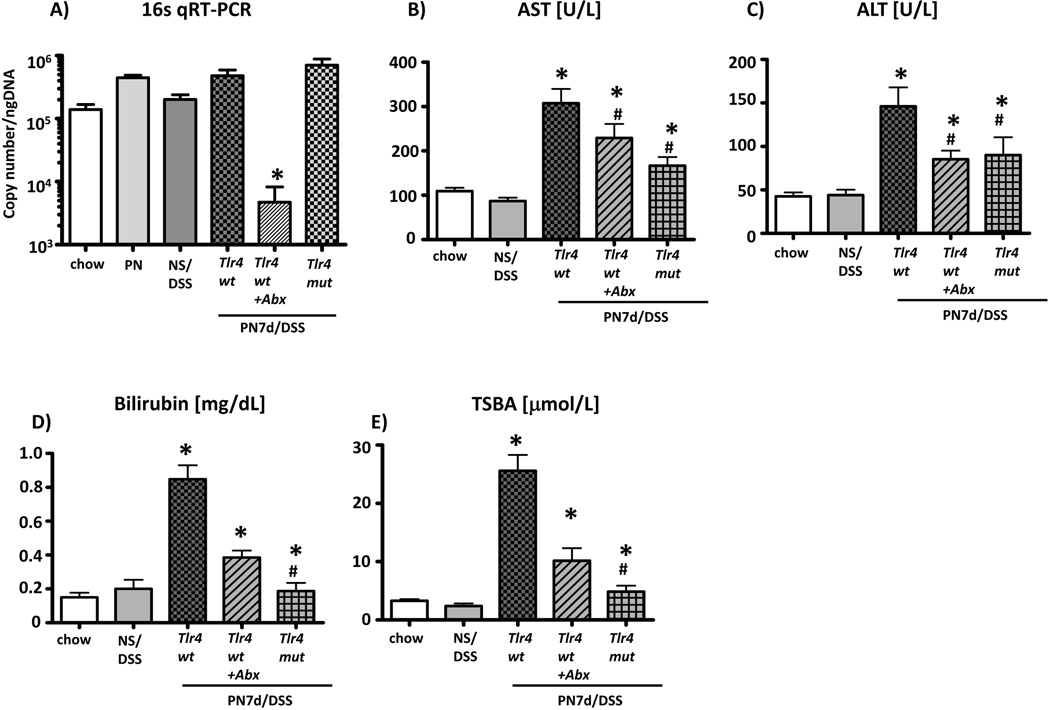

Kupffer cell activation and liver injury are dependent on the intestinal microbiota

The intestinal microbiota are a major source of intestinal-derived LPS. We therefore tested if intestinal microbiota were involved in promoting Kupffer cell activation and liver injury in the mouse model. Intestinal microbiota were suppressed by exposing wild type PN/DSS7d mice ad lib to an oral cocktail of four broad-spectrum antibiotics in the drinking water during the entire 7-day period of PN infusion (PN/DSS tlr4wt+Abx mice). qRT-PCR analysis of copy numbers of bacterial 16S DNA in colonic feces demonstrated a >98% reduction (4.8*105 →4.7*103, p<0.05) of the intestinal microbiota in PN/DSS tlr4wt+Abx trated mice (n=7) relative to PN/DSS7d tlr4wt (n=13) mice (Figure 5A). Kupffer cell mRNA expression of IL6, TNFα and TGFβ was significantly lower (p<0.05) in PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx mice compared to PN/DSS7d tlr4wt mice, and similar to expression in Kupffer cells isolated from NS/DSS mice (p>0.05) (Figure 3A–C). Antibiotic treatment was also associated with a significant reduction in liver injury (AST, ALT) (Figure 5B–C). Cholestasis was almost completely prevented in PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx mice, with TSBA and total bilirubin values comparable to NS/DSS7d (n=12) and chow fed controls (n=20) (Figure 5D–E). Thus, oral antibiotic treatment reduced colonic bacterial load and prevented both Kupffer cell activation and liver injury.

Figure 5. Liver injury is attenuated after suppression of bowel flora or ablation of TLR4 signaling.

(A) qRT-PCR to determine copy number of bacterial 16S DNA genes in colonic stool samples after oral antibiotic treatment. Note significant reduction in bacterial load in stool from PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx mice. Note that ablation of TLR4 signaling does not reduce bacterial load in stool of PN/DSS7d tlr4mut mice compared to wild type mice; *p<0.05 PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx vs. other groups; determined by One-Way ANOVA. Hepatocyte injury (B-C) and cholestasis (D-E) were attenuated in PN/DSS wild type mice that were treated with oral antibiotics (PN/DSS7d tlr4 wt+Abx; n=11) or had non-functional TLR4 signaling (PN/DSS7d tlr4mut; n=12) compared to PN/DSS wild type mice (PN/DSS7d tlr4wt; n=15). NS/DSS mice (n=12) and untreated chw fed mice (n=20) served as controls. Mean values and SEM are depicted. *p<0.05 PN/DSS tlr4wt vs. controls and PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx and PN/DSS7d tlr4mut vs. PN/DSS tlr4wt ; # p<0.05 PN/DSS7d tlr4wt+Abx and PN/DSS7d tlr4mut vs. controls; determined by One-Way ANOVA.

TLR4 signaling significantly contributes to Kupffer cell activation and liver injury

We next examined the role of TLR4 signaling in this model by utilizing TLR4 mutant mice with defective TLR4 signaling. TLR4 mutant (PN/DSS7d tlr4mut; n=11) and wild type (PN/DSS7d tlr4wt; n=10) mice underwent DSS pre-treatment followed by PN infusion for 7 days. IL6 transcription (tested as a representative canonical cytokine since RNA amounts were very limited from TLR4 mutant mice due to reduced numbers of purified Kupffer cells) in Kupffer cells purified from PN/DSS7d tlr4mut mice was markedly reduced compared to PN/DSS7d tlr4wt mice and was similar to NS/DSS control mice (Figure 3B). Importantly, hepatocyte injury and cholestasis were significantly attenuated in PN/DSS7d tlr4mut mice, with significant reductions in AST and ALT levels (p<0.05) and marked reductions in bilirubin and TSBA compared to PN/DSS7d tlr4wt treated mice (Figure 5B–E).

DISCUSSION

Although the pathogenesis of PNALI is poorly understood, the severity and chronicity of PNALI are clearly increased in infants with underlying intestinal inflammation, presumed small bowel bacterial overgrowth and increased intestinal permeability (4). These factors together may increase translocation of bacteria and/or microbial derived TLR agonists into the portal circulation. Of note, Kupffer cell hyperplasia and inflammation are characteristic of the liver histopathology in human infants with PNALI (11).

The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that an early upstream event in the pathogenesis of PNALI is the initial activation of Kupffer cells by intestinal-derived TLR agonists. We therefore designed a novel mouse model that mimics the early pathophysiology present in the human infant at greatest risk for PNALI by providing continuous PN infusion combined with intestinal injury and increased permeability. We took advantage of the known effects of DSS on intestinal integrity, which allowed us to modulate (i.e. DSS dose and duration) the severity of intestinal inflammation so that the mice could tolerate PN without the usual weight loss observed in most DSS models (19). Using this mouse model, our study has provided evidence that early liver injury in PNALI is induced by a mechanism that involves TLR4 dependent activation of Kupffer cells by LPS absorbed from the gut microbiota. Intestinal injury by itself or PN infusion alone was insufficient to induce Kupffer cell activation or biochemical evidence of liver injury. Kupffer cell activation in PN/DSS7d treated mice was demonstrated by increased transcription of canonical TLR signaling-NFκB dependent cytokines. Whole liver homogenates from PN/DSS7d mice did not show increased transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, providing evidence that isolated activation of the Kupffer cell was a key early event in this liver injury. As might be expected, the very early phases of this liver injury were not associated with visible histopathological alterations of the liver. As in human infants with intestinal failure, PN infusion for at least several weeks may be required for the development of histologic lesions (20). Indeed, after 28 days of PN infusion following DSS pre-treatment, we observed marked Kupffer cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy (suggestive of Kupffer cell activation), which was associated with hepatic inflammatory infiltrates, hepatocellular apoptosis and parenchymal peliosis. Importantly, these lesions at 28 days were associated with increased transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines from liver homogenate, suggesting a progression and broadening of the inflammatory process.

The observation that Kupffer cell activation and liver injury were observed only in PN mice with concomitant intestinal injury is consistent with the proposed pathogenesis of other chronic liver injuries, in which absorption of TLR agonists through a disrupted intestinal barrier into the portal circulation results in activation of TLR signaling pathways in Kupffer cells with subsequent generation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic mediators (12, 21). Under normal circumstances a functional intestinal epithelial barrier ensures that only trace amounts of LPS and other TLR agonists enter into the portal/sinusoidal circulation in healthy humans and rodents. Our data support the notion that disruption of the intestinal barrier function in PN/DSS mice led to increased absorption of LPS into the portal circulation with subsequent activation of Kupffer cells.

Using a genetic approach, we have demonstrated that interruption of LPS-TLR4 signaling in TLR4 mutant mice attenuated Kupffer cell transcription of IL6. Only a small number of Kupffer cells could be isolated from TLR4 mutant mice which limited the number of cytokines that could be examined by mRNA expression; thus, we focused our analysis on IL6 as a canonical marker for TLR dependent Kupffer cell activation. Importantly, attenuated Kupffer cell activation was associated with reduced liver injury and cholestasis. These findings are in keeping with previous studies using TLR4 mutant mice in a bile duct ligated model of cholestasis in which progression to fibrosis was attenuated by disrupting TLR4 signaling pathways (12). Our data also demonstrate that liver injury, albeit significantly reduced, still developed to a limited extent in TLR4 mutant mice. This finding implies that other TLR signaling pathways or other cell types may also be involved in the liver injury in this model. In this regard, TLR9 dependent activation of murine Kupffer cells with subsequent generation of pro-inflammatory IL1β has been shown to be critically involved in progression from steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis (22). Moreover, Lichtman et al. have demonstrated that intestinal-derived peptidoglycan, a TLR2 agonist, played a major role in liver injury in rats with bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine in a Kupffer cell-dependent mechanism (23). Further studies using pharmacological and/or genetic ablation of individual TLR signaling components isolated to Kupffer cells are required for a more detailed definition of Kupffer cell activation in this model. Our study also identified that CD11b positive macrophages isolated from the spleens of PN/DSS mice did not demonstrate increased transcription of these cytokines, indicating that systemic activation of macrophages (as might be observed in bacteremia and sepsis) did not play a role. The most likely factor in this mouse model that could account for this hepatic macrophage specificity is intestinal absorption of TLR agonists into the portal circulation triggering TLR signaling in sinusoidal Kupffer cells. However, it should be noted that treatment of mice with DSS alone did not initiate liver injury or Kupffer cell activation; thus factors associated with the infusion of PN (e.g. lack of enteral feedings or constituents of the PN solution) must be involved as well in the development of liver injury and Kupffer cell activation.

Recent studies have implicated the intestinal microbiota in promoting liver injury and progression to fibrosis by a mechanism that involves TLR dependent activation of Kupffer cells (12). To test the role of intestinal microbiota in this mouse model, we employed an oral cocktail of non-absorbable broad-spectrum antibiotics during the time of PN infusion, which significantly reduced intestinal bacterial flora, and both attenuated liver injury and prevented the transcriptional induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in Kupffer cells. The antibiotic cocktail used in this study has been shown to not alter TLR4 expression and responsiveness to LPS in Kupffer cells, or influence the number of Kupffer cells in the liver (12). Thus, reduction of intestinal bacterial load appeared to have inhibited activation of Kupffer cells and the development of liver injury and cholestasis. Although we did not directly examine the intestinal microbiome in these experiments, a complete metagenomic characterization of the intestinal microbiome in this mouse model is underway and will be the subject of a future report (24).

One intriguing aspect of this mouse model is that Kupffer cell activation and liver injury were not observed in mice receiving either DSS or PN alone, but that the combination was required. Consequently, based on this study and the work of others, we propose that the early stages in the pathogenesis of PNALI may involve the following. The lack of enteral feedings during PN infusion and underlying intestinal dysfunction and dysmotility promote bacterial overgrowth, which enhances intestinal inflammation and compromises intestinal barrier function (4–6, 9). Together with pre-existing intestinal injury and the presumed increased intestinal permeability of infants (8), absorption of intestinal-derived TLR agonists is enhanced. Kupffer cell activation is then induced through TLR signaling and potentially by pro-inflammatory eicosanoids as well as lipid peroxidation products derived from omega-6 fatty acids present in the standard soy lipid-based PN (25). Cholestasis and liver injury may be further amplified by the inhibitory effects on the expression of canalicular bile acid transporters by pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL6) derived from activated Kupffer cells (26) and from soy lipid-derived phytosterols in the PN solution (27). We propose that this mouse model will be useful in elucidating the pathogenesis of early initiating mechanisms of PNALI and in further characterization of the role of the gut-liver axis in liver disease.

Supplementary Material

Focal sub-mucosal mixed inflammation in the colon of DSS pre-treated mice. H&E (A, D) stains demonstrate focal inflammation in panel A (arrow) that opposes healthy colon area (*). Inflamed section is depicted in higher power (20×) in panel B. F4/80 (B, E) and MPO (C, F) stains of the same sections in low power (10×; B, C) and high power (20×; E, F) demonstrate presence of macrophages and activated neutrophils.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Daniel H. Teitelbaum, MD (University of Michigan) for assistance with the development of the PNALI mouse model.

Financial Support: This project was supported in part by NIH grant 3P30DK048520 and by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSA Grants KL2 RR025779 and UL1RR025780. Its contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Abbreviations

- PN

parenteral nutrition

- PNALI

parenteral nutrition associated liver injury

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TLR

toll like receptor

- DSS

dextran sulphate sodium

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- IL

interleukin

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- CVC

central venous catheter

- NS

normal saline

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- TSBA

total serum bile acids

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- H&E

Hematoxylin & Eosin

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilmore DW, Dudrick SJ. Growth and development of an infant receiving all nutrients exclusively by vein. JAMA. 1968;203:860–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beale EF, Nelson RM, Bucciarelli RL, Donnelly WH, Eitzman DV. Intrahepatic cholestasis associated with parenteral nutrition in premature infants. Pediatrics. 1979;64:342–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goulet O, Ruemmele F. Causes and management of intestinal failure in children. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S16–S28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman SS, Loseke CA, Lupo JV, Young RJ, Murray ND, Pinch LW, et al. Influence of bacterial overgrowth and intestinal inflammation on duration of parenteral nutrition in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr. 1997;131:356–361. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)80058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierro A, van Saene HK, Donnell SC, Hughes J, Ewan C, Nunn AJ, et al. Microbial translocation in neonates and infants receiving long-term parenteral nutrition. Arch Surg. 1996;131:176–179. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430140066018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wildhaber BE, Yang H, Spencer AU, Drongowski RA, Teitelbaum DH. Lack of enteral nutrition--effects on the intestinal immune system. Journal of Surgical Research. 2005;123:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor SF, Sondheimer JM, Sokol RJ, Silverman A, Wilson HL. Noninfectious colitis associated with short gut syndrome in infants. J Pediatr. 1991;119:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver LT, Laker MF, Nelson R. Intestinal permeability in the newborn. Archives of disease in childhood. 1984;59:236–241. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Finaly R, Teitelbaum DH. Alteration in epithelial permeability and ion transport in a mouse model of total parenteral nutrition. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1118–1125. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000053523.73064.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan JP. Intestinal endotoxins as mediators of hepatic injury--an idea whose time has come again. Hepatology. 1989;10:887–891. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchman AL, Iyer K, Fryer J. Parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease and the role for isolated intestine and intestine/liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2006;43:9–19. doi: 10.1002/hep.20997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thurman RG., II Alcoholic liver injury involves activation of Kupffer cells by endotoxin. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G605–G611. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.4.G605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spruss A, Kanuri G, Wagnerberger S, Haub S, Bischoff SC, Bergheim I. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the development of fructose-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:1094–1104. doi: 10.1002/hep.23122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu M-Y, Huffel CV, Du X, et al. Defective LPS Signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr Mice: Mutations in Tlr4 Gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagarasan S, Muramatsu M, Suzuki K, Nagaoka H, Hiai H, Honjo T. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science. 2002;298:1424–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.1077336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tannock GW, Munro K, Harmsen HJ, Welling GW, Smart J, Gopal PK. Analysis of the fecal microflora of human subjects consuming a probiotic product containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus DR20. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2578–2588. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2578-2588.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadkarni MA, Martin FE, Jacques NA, Hunter N. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology. 2002;148:257–266. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirtz S, Neufert C, Weigmann B, Neurath MF. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zambrano E, El-Hennawy M, Ehrenkranz RA, Zelterman D, Reyes-Mugica M. Total parenteral nutrition induced liver pathology: an autopsy series of 24 newborn cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7:425–432. doi: 10.1007/s10024-001-0154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Signalling pathways in alcohol-induced liver inflammation. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1258–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrasek J, Dolganiuc A, Csak T, Kurt-Jones EA, Szabo G. Type I interferons protect from Toll-like receptor 9-associated liver injury and regulate IL-1 receptor antagonist in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:697–708. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.020. e694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lichtman SN, Okoruwa EE, Keku J, Schwab JH, Sartor RB. Degradation of endogenous bacterial cell wall polymers by the muralytic enzyme mutanolysin prevents hepatobiliary injury in genetically susceptible rats with experimental intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1313–1322. doi: 10.1172/JCI115996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Kasmi KC, Anderson AL, Devereaux MW, Fillon SA, Harris JK, Sokol RJ. Specific Alterations in the Intestinal Microbiome are Associated with Kupffer Cell Activation and Liver Injury in a Novel Mouse Model of Parenteral Nutrition Associated Liver Injury (PNALI) [Abstract] :1021A–1119A. [Google Scholar]; Hepatology. 2010;52:1021A–1119A. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calder PC. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1505S–1519S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1505S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosters A, Karpen SJ. The role of inflammation in cholestasis: clinical and basic aspects. Seminars in liver disease. 2010;30:186–194. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter BA, Taylor OA, Prendergast DR, Zimmerman TL, Von Furstenberg R, Moore DD, et al. Stigmasterol, a soy lipid-derived phytosterol, is an antagonist of the bile acid nuclear receptor FXR. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:301–306. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181256492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Focal sub-mucosal mixed inflammation in the colon of DSS pre-treated mice. H&E (A, D) stains demonstrate focal inflammation in panel A (arrow) that opposes healthy colon area (*). Inflamed section is depicted in higher power (20×) in panel B. F4/80 (B, E) and MPO (C, F) stains of the same sections in low power (10×; B, C) and high power (20×; E, F) demonstrate presence of macrophages and activated neutrophils.