Abstract

Background

A consensus is lacking on a uniform reconstructive algorithm for patients with locally advanced breast cancer who require postmastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT). Both delayed autologous and immediate prosthetic techniques have inherent advantages and complications. The study hypothesis is that implants are more cost-effective than autologous reconstruction in the setting of PMRT because of immediate restoration of the breast mound.

Methods

A cost-effectiveness analysis model using the payer perspective was created comparing delayed autologous and immediate prosthetic techniques against the do-nothing option of mastectomy without reconstruction. Costs were obtained from Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2010 database. Effectiveness was determined using the BREAST-Q patient reported outcome measure. A Breast-QALY was considered one year of perfect breast health related quality of life. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated for both treatments compared to the do-nothing option.

Results

BREAST-Q scores were obtained from patients who underwent immediate prosthetic reconstruction (n=196), delayed autologous reconstruction (n=76) and mastectomy alone (n=71). The ICER for immediate prosthetic and delayed autologous reconstruction compared to mastectomy alone was $57,906 and $102,509 respectively. Sensitivity analysis showed that the ICER for both treatment options decreased with increasing life expectancy.

Conclusion

For patients with advanced breast cancer who require PMRT, immediate prosthetic based breast reconstruction is a cost-effective approach. Despite high complication rates, implant use can be rationalized based on low cost as well as HRQOL benefit derived from early breast mound restoration. If greater life expectancy is anticipated, autologous transfer is cost-effective as well and may be a superior option.

Introduction

Locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) is a term used to describe advanced forms of non-metastatic breast cancer, which often require adjuvant treatments such as postmastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT). LABC is notable for its high relapse rates with shortened life span; median survival for women with stage III breast cancer is 4.9 years.1 Radiotherapy can impact multiple aspects of breast reconstruction, hence plastic surgeons are faced with the dilemma of determining the correct timing and method to offer patients with LABC. Three competing options are frequently discussed with patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The first approach is to perform the mastectomy, but delay autologous reconstruction until after completion of radiotherapy.2,3 The alternative is to proceed with immediate prosthetic based breast reconstruction at the time of mastectomy.2,4 Finally, there is the do nothing approach of mastectomy alone. Each choice is associated with considerable tradeoffs.

The need for radiotherapy may be viewed as a relative contraindication to immediate prosthetic reconstruction. For example, radiating an implant is associated with higher rates of capsular contracture, infection, device exposure, and explantation as well as lower levels of patient satisfaction. 4-6 Despite these drawbacks, increasing numbers of immediate implant reconstructions are performed in unfavorable scenarios, albeit with a greater risk profile, because of the absent donor site morbidity.7-9 There is also the potential benefit of early breast mound restoration especially for a patient threatened by a curtailed lifespan. Finally, once radiation has been completed, expansion cannot reliably be performed thereby eliminating prosthetic methods as an option for many patients.

For a variety of reasons, autologous reconstruction has traditionally not been offered until after completion of radiotherapy. First, complications following flap transfer can potentially delay the timely delivery of radiation, especially when neoadjuvant chemotherapy has already been administered. Second, to avoid radiation induced side effects to the flap such as fat necrosis or volume loss. Importantly, autologous reconstruction is preserved as a lifeboat for definitive breast mound replacement following radiation damage to the chest wall.2,3 This treatment algorithm suffers from the diminished quality of life associated with prolonged absence of the breast mound.

Variability in cost, complication rates, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) associated with each of these options in the setting of PMRT is an ideal application for cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA). The specific aim of the current study is to develop a cost-effectiveness model for women undergoing breast reconstruction in the setting of PMRT using BREAST-Q scores as the principle outcome measure. The hypothesis is that for women with LABC who require PMRT, immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction is the most cost effective option because of the quality of life benefit derived from early breast mound replacement.

Methods

An institutional review board approval was obtained prior to study initiation. The methodology used for the cost-effectiveness analysis was based on guidelines set by the US Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine.10 Patient reported outcomes (PRO) data was obtained for those with LABC at MSKCC who underwent one of three treatment pathways: 1) immediate tissue expander placement followed by exchange to permanent implant with subsequent PMRT, 2) mastectomy followed by PMRT with delayed autologous reconstruction at postoperative year three, the median time for delayed flap transfer in the cohort, 3) mastectomy (do-nothing option).

A payer perspective was adopted for the analysis so only hospital charges were included. A decision tree model (TreeAge Pro 2014, Mass., USA) was developed to compare the cost-effectiveness of the three treatment options. Complications with relevant probabilities were included for each treatment based on a PubMed literature review.5,11-19 Outcomes were considered mutually exclusive to allow probabilities to add up to one; therefore, each patient could have only one complication. The base case analysis for the study was determined using a weighted average of years remaining to live for a typical woman diagnosed at age of 48 years with stage 2 or 3-breast cancer (American College of Surgeons National Cancer Database).1 This was determined to be 7 years for a woman with LABC.1

Cost data

Procedure and complications were collated by International Classification of Disease Procedure codes, version 9 (ICD-9). Mean hospital charges for ICD-9 procedures and complications were obtained from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database (NIS), 2010. While hospital charges can differ, potential variation should be overcome by the large number of centers included in the NIS. For prosthetic based reconstruction, the charges of the exchange from the tissue expander to the permanent implant were included. Since, long-term complications could occur anytime during the 7-year life span, charges for those were discounted by 3% for both implant (e.g. capsular contracture) and autologous reconstruction (e.g. hernia) treatment arms.20

Effectiveness data

The effectiveness measure was derived from the BREAST-Q using scores expressed as a numerical rating scale ranging from 0-100 and reported as Breast - Quality adjusted life years (Breast-QALY). This is possible because the BREAST-Q was developed using the Rasch psychometric model and provides interval level measurement.21 For each of the six BREAST-Q scales, items are summed and transformed to a 0 to 100 scale, with greater values indicating higher satisfaction and superior levels of breast related quality of life. A score of 100 was assigned to the scale on abdominal wall morbidity for women undergoing immediate prosthetic reconstruction and mastectomy alone, whereas patient reported scores were used for delayed autologous reconstruction. At present, preference weighting for the six BREAST-Q scales is not available; therefore, the mean value from the six scales was used to generate Breast-QALYs. Clinically a Breast-QALY can be interpreted as 1 year of perfect breast health related quality of life. Not all of the patients in the mastectomy only group received radiation therapy; however, this would only lower Breast-QALYs further.

Effectiveness of the different health states (i.e. complications) was determined by adjusting mean BREAST-Q scores by complication rates as reported in the literature using the following formula22:

Duration of health state*utility of health state + (number of healthy years remaining-duration of health state)*utility of successful breast reconstruction

A health state reflects how well or how poorly people are doing with respect to a given aspect of a particular disease or condition. Short-term complications were assigned a duration of less than 1 year, whereas long-term complication (e.g. capsular contracture, implant rupture, delayed infection) could occur at any time until death.

Decision tree analysis was performed to determine the expected value (Cost/Breast-QALY) for each treatment. Competing options were compared using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). ICER is the ratio of the change in costs to change in Breast-QALYs between two options:

[cost of intervention 1- cost of intervention 2]/[effectiveness of intervention 1-effectiveness of intervention 2]

In the current study, the ICER can be interpreted as the increased cost for obtaining 1 year of perfect breast-related health when an immediate implant or delayed autologous reconstruction is chosen compared to mastectomy alone. An ICER less than the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $100,000/QALY has been suggested as being cost-effective for developed countries.23 A one-way sensitivity analysis for varying life expectancy was performed.

Results

BREAST-Q scores were obtained from a total of 343 patients: two-staged immediate prosthetic reconstruction (n=196), delayed autologous reconstruction (n=76), and mastectomy alone (n=71). The decision tree for the base case analysis, which includes weight adjusted complications rates, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decision Tree comparing three competing options for a 48-year-old woman diagnosed with locally advanced breast cancer requiring radiotherapy and a life expectancy of 7 years. The square is the treatment decision node. The circle is the chance node representing the probability of an event occurrence. The triangle is the terminal node representing the point at which no subsequent events are assumed to occur. Hospital charges and cumulative Breast-QALYs associated with successful surgery and complications are shown.

Costs (Hospital Charges)

Costs from the provider perspective were determined based on the charges of the procedure weighted by the relative probabilities of complications versus successful surgery. Table 1 displays the resulting costs of the three possible options. Compared to mastectomy alone, the incremental cost of immediate TE/implant was $38,218, whereas for delayed autologous reconstruction it was $77,907.

Table 1. Base case cost-effectiveness analysis for three surgical options.

| Treatment | Cost ($) | Incremental Cost ($) | Effect (Breast-QALY) | Incremental Effect (Breast-QALY) | ICER ($/Breast-QALY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mastectomy without Reconstruction | 23,297 | 4.03 | |||

| Immediate TE/Implant Reconstruction | 61,515 | 38,218 | 4.69 | 0.66 | 57,906 |

| Delayed Autologous Reconstruction | 101,204 | 77,907 | 4.79 | 0.76 | 102,509 |

ICER for Delayed Autologous Reconstruction compared to Immediate TE/Implant Reconstruction = ($101,204 - $61,515)/(4.79 – 4.69) = $ 396,890/Breast-QALY.

Effectiveness: Breast-QALYs

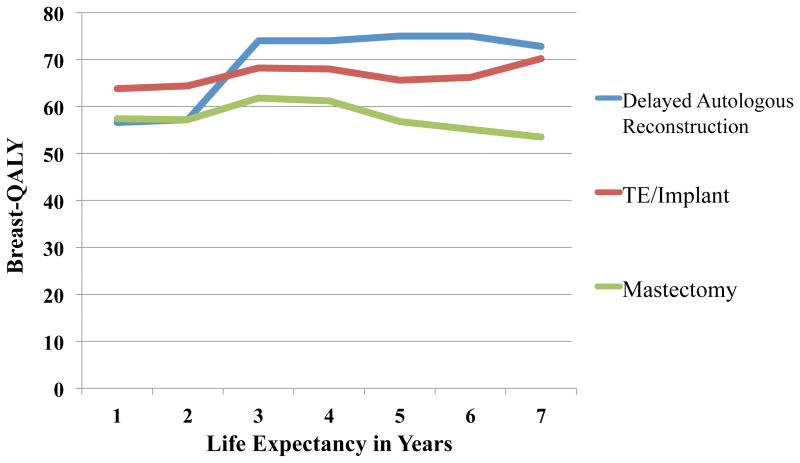

Yearly Breast-QALYs were lowest for patients who underwent mastectomy alone, with consistently greater values in women who underwent immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction (Figure 2). Delayed autologous transfer initially had low Breast-QALYs, which subsequently achieved levels above implants after postoperative year 2 when this reconstruction was performed. Cumulative Breast-QALYs for the base case analysis were highest for autologous reconstruction (4.79) followed by implant based reconstruction (4.69) and mastectomy alone (4.03). The incremental Breast-QALY of an immediate TE/implant and delayed autologous reconstruction compared to mastectomy were 0.66 and 0.76 respectively (Table 1).

Figure 2. Breast-QALYs over time for three competing alternatives.

Cost Effectiveness Analysis

The ICER was calculated as the ratio of the difference in cost to the difference in Breast-QALYs. For a patient with locally advanced breast cancer who has a life expectancy of 7 years, the cost for each additional Breast-QALY gained with an immediate TE/implant and delayed autologous reconstruction compared with no reconstruction is $57,906 and $102,509 respectively (Table 1).

Sensitivity Analysis

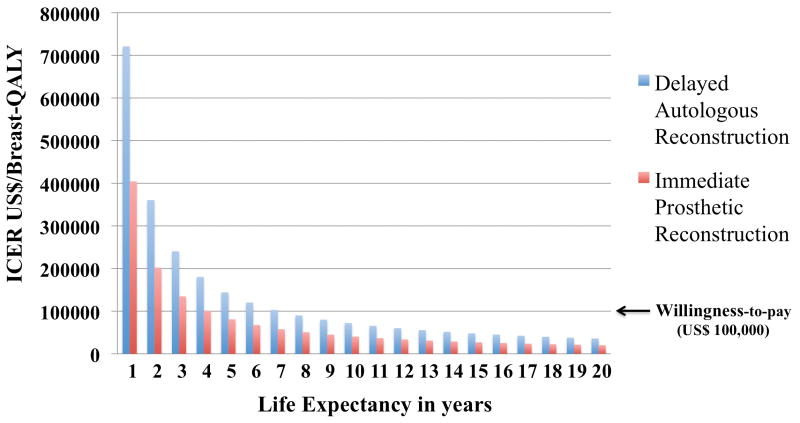

A one-way sensitivity analysis varying the life expectancy was performed for immediate TE/implant and delayed autologous reconstruction versus mastectomy alone (Figure 3). As life expectancy increases, the ICER for both implants and delayed autologous reconstruction continually decreases; however, at each time point implants are more cost effective. Delayed autologous reconstruction falls below the WTP threshold at a life expectancy of 8 years.

Figure 3. One-way sensitivity analysis for varying life expectancy.

Discussion

In the setting of PMRT, immediate prosthetic and delayed autologous reconstruction are frequent methods of recreating the breast mound.24 Because of the divergent nature of these two algorithms, a treatment consensus has not been established. CEA can be a helpful tool to resolve such dilemmas as it simultaneously incorporates information on both cost and quality of life into a single analysis. The findings are particularly meaningful, as utilization of healthcare resources is requiring increasing justification with passage of the Affordable Care Act.

HRQOL over time for women receiving PMRT was evaluated using the BREAST-Q patient reported outcome measure (Figure 2). Compared to women undergoing mastectomy alone or delayed autologous reconstruction, immediate prosthetic reconstruction was associated with the greatest HRQOL for the first two years postoperatively. However, at postoperative year 3, following delayed autologous reconstruction, BREAST-Q scores exceed that of implants (and mastectomy alone). These are parallel findings to previous studies.25-27 First, reconstruction with implants, compared to mastectomy alone, is associated with greater HRQOL thereby providing a rationale for early breast mound replacement. Second, autologous reconstruction is associated with greater HRQOL and patient satisfaction when compared directly to implants. The current study provides novel information by demonstrating consistency of these findings in the setting of PMRT.

A weighted average of overall costs derived for each treatment algorithm from the decision tree is shown in Table 1. When all factors, including complications are tallied, mastectomy alone is least expensive, followed by implants and delayed autologous transfer; however, none of the options is dominated. That is, although autologous transfer has greater hospital charges, it should also be considered because of its incremental gain in HRQOL. Conversely, if autologous transfer was more expensive, but had lower HRQOL scores, then it would be eliminated from the final cost-effectiveness analysis.

When cost and HRQOL data are combined to yield the ICER (Table 1), the cost for an additional Breast-QALY compared to mastectomy alone is $ 102,509 and $ 57,906 for delayed autologous and immediate implants respectively. Clinically this can be interpreted to be the cost for obtaining a year of prefect breast HRQOL for each procedure. Using a WTP threshold of $100,000, immediate implant placement, but not delayed autologous transfer, is cost effective compared to mastectomy without reconstruction. Furthermore, if delayed autologous is compared directly to immediate implant reconstruction, the ICER is $396,890. This finding reflects the high cost associated with autologous tissue relative to the small gain in Breast-QALYs compared to prosthetic breast reconstruction. In clinical terms, the HRQOL benefits derived from delayed autologous reconstructions are not realized for patients with an abbreviated lifespan to make it cost effective.

For the base case analysis, a life expectancy of 7 years was used; however, in reality it varies for patients with LABC. A one-way sensitivity analysis demonstrates that as life expectancy increases, the ICER for delayed autologous reconstruction compared to mastectomy alone falls below the WTP threshold at postoperative year 8 (Figure 3). Thus for short-term survivors the model favors the gains in HRQOL associated with early breast mound replacement with implants; however, as a woman's longevity increases, the greater upfront charges of autologous transfer are overcome by relative gains in HRQOL compared to implants.

Alternative approaches to the sequencing of breast reconstruction and radiation, although not routinely performed at our center, are worth considering in light of the current findings. Delayed immediate reconstruction is an approach whereby all women potentially requiring PMRT, who are interested in breast reconstruction, receive a tissue expander at the time of mastectomy28. Patients who do not need PMRT based on final pathology are converted to autologous tissue within 2 weeks whereas those in need of radiation undergo the expansion process. While this approach creates logistical issues, it enables all women to derive the HRQOL benefits derived from early breast mound creation demonstrated in the current study (Figure 2). Another consideration is to proceed with delivery of PMRT to an immediate autologous transfer. In this scenario, the patient derives the long-term benefits of autologous reconstruction along with the advantages of immediate mound restoration; however, evidence is conflicting about the safety of radiating autologous breast flap with variable rates of fat necrosis, revision and no information on patient satisfaction.29 For either of these options, PRO data is not available; hence they were unable to be considered in the current CEA. However, as PRO data from centers using these approaches becomes available, future studies could evaluate these algorithms.

The main strength of the current study is that the effectiveness measure was derived from PRO data. This provides a more realistic quality of life assessment than utilities derived from surveys of plastic surgeons or healthy volunteers.30 Limitations are inherent to any CEA where certain assumptions need to be made for model creation. For example, these include but are not limited to only one complication per person, lifespan of 7 years following diagnosis, and variations in BREAST-Q scores. Moreover, mean charges were calculated from the NIS database for each treatment option and complication for the year 2010; however, variation in charges may exist. These variations should not significantly impact the outcomes since differences affect each intervention in a similar way. There are also no randomized controlled trials comparing mastectomy alone, implants and autologous breast reconstructions in the setting of PMRT, so the probabilities included in our decision tree represent a weighted average of pooled complication rates reported in the literature.

The results of our study should not be interpreted as immediate implant based reconstruction is better than delayed autologous reconstruction for women requiring PMRT. Rather we recommend an individualized approach to each patient in deciding on an optimal strategy. Nevertheless, plastic surgeons concerned about the high complication rates associated with implants in the setting of anticipated PMRT could cite the current findings as support for their use.

Conclusion

For a woman with locally advanced breast cancer who requires PMRT, immediate implant based breast reconstruction is cost-effective compared to delayed autologous or mastectomy without reconstruction. Despite high complication rates, implant use can be rationalized based on its relatively low cost as well as HRQOL benefit derived from early breast mound restoration. If greater life expectancy is anticipated, autologous transfer is cost-effective as well and may be a superior option because of greater associated long-term HRQOL.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The BREAST-Q is owned by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Dr. Pusic is a co-developer of the BREAST-Q and receives a share of licensing revenues based on the inventor-sharing policies of this institution. None of the other authors have any financial information to disclose.

References

- 1.American College of Surgeons. [Accessed May 19, 2015];National Cancer Database. Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality%20programs/cancer/ncdb.

- 2.Kronowitz SJ, Robb GL. Radiation therapy and breast reconstruction: a critical review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):395–408. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelley BP, Ahmed R, Kidwell KM, Kozlow JH, Chung KC, Momoh AO. A systematic review of morbidity associated with autologous breast reconstruction before and after exposure to radiotherapy: are current practices ideal? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1732–1738. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3494-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Momoh AO, Ahmed R, Kelley BP, et al. A systematic review of complications of implant-based breast reconstruction with prereconstruction and postreconstruction radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(1):118–124. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3284-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordeiro PG, Albornoz CR, McCormick B, Hu Q, Van Zee K. The impact of postmastectomy radiotherapy on two-stage implant breast reconstruction: an analysis of long-term surgical outcomes, aesthetic results, and satisfaction over 13 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(4):588–595. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordeiro PG, Albornoz CR, McCormick B, et al. What is the Optimum Timing of Post-mastectomy Radiotherapy in Two-stage Prosthetic Reconstruction: Radiation to the Tissue Expander or Permanent Implant? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(6):1509–1517. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal S, Kidwell KM, Farberg A, Kozlow JH, Chung KC, Momoh AO. Immediate Reconstruction of the Radiated Breast: Recent Trends Contrary to Traditional Standards. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(8):2551–2559. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4326-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albornoz CR, Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL, et al. Diminishing relative contraindications for immediate breast reconstruction: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(4):788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albornoz CR, Cordeiro PG, Farias-Eisner G, et al. Diminishing relative contraindications for immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(3):363e–369e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, editors. Cost- Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran NV, Chang DW, Gupta A, Kroll SS, Robb GL. Comparison of Immediate and Delayed Free TRAM Flap Breast Reconstruction in Patients Receiving Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(1):78–82. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams JK, Carlson GW, Bostwick J, 3rd, Bried JT, Mackay G. The effects of radiation treatment after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(5):1153–1160. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199710000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momoh AO, Colakoglu S, de Blacam C, Gautam S, Tobias AM, Lee BT. Delayed Autologous Breast Reconstruction After Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy: Is There an Optimal Time? Ann Plast Surg. 2012;69(1):14–18. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31821ee4b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spear SL, Ducic I, Low M, Cuoco F. The effect of radiation on pedicled TRAM flap breast reconstruction: outcomes and implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):84–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee BT, A Adesiyun T, Colakoglu S, et al. Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy and Breast Reconstruction: An Analysis of Complications and Patient Satisfaction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):679–683. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181db7585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin SM, Patel N, Disa JJ. Outcomes of Delayed Abdominal-based Autologous Reconstruction Versus Latissimus Dorsi Flap Plus Implant Reconstruction In Previously Irradiated Patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;69(4):380–382. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31824b3d6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL, Disa JJ, McCormick B, VanZee K. Irradiation after immediate tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction: Outcomes, Complications, Aesthetic Results, and Satisfaction Among 156 Patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(3):877–881. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000105689.84930.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho A, Cordeiro P, Disa J, et al. Long-term outcomes in breast cancer patients undergoing immediate 2-stage expander/implant reconstruction and postmastectomy radiation. Cancer. 2012;118(9):2552–2559. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nava MB, Pennati AE, Lozza L, Spano A, Zambetti M, Catanuto G. Outcome of different timings of radiotherapy in implant-based breast reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(2):353–359. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821e6c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudmik L, Drummond M. Health economic evaluation: important principles and methodology. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(6):1341–1347. doi: 10.1002/lary.23943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345–353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thoma A, Veltri K, Khuthaila D, Rockwell G, Duku E. Comparison of the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap and free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap in postmastectomy reconstruction: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(6):1650–1661. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000117196.61020.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness--the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):796–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1405158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berbers J, van Baardwijk A, Houben R, et al. Reconstruction: before or after postmastectomy radiotherapy? A systematic review of the literature. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(16):2752–2762. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu ES, Pusic AL, Waljee JF, et al. Patient-reported aesthetic satisfaction with breast reconstruction during the long-term survivorship period. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ab10b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy CM, Mehrara BJ, Long T, et al. Chest and upper body morbidity following immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(1):107–112. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3231-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atisha DM, Rushing CN, Samsa GP, et al. A national snapshot of satisfaction with breast cancer procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(2):361–369. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kronowitz SJ, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM, et al. Delayed-immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(6):1617–1628. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000117192.54945.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rochlin DH, Jeong AR, Goldberg L, et al. Postmastectomy radiation therapy and immediate autologous breast reconstruction: Integrating perspectives from surgical oncology, radiation oncology, and plastic and reconstructive surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111(3):251–257. doi: 10.1002/jso.23804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grover R, Padula WV, Van Vliet M, Ridgway EB. Comparing five alternative methods of breast reconstruction surgery: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):709e–723e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a48b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]