Abstract

Rab11a and Rab8a are ubiquitous small GTPases shown as required for rhodopsin transport in Xenopus laevis and zebrafish photoreceptors by dominant negative (dn) disruption of function. Here, we generated retina-specific Rab11a (retRab11a) and Rab8a (retRab8a) single and double knockout mice to explore the consequences in mouse photoreceptors. Rhodopsin and other outer segment (OS) membrane proteins targeted correctly to OS and electroretinogram (ERG) responses in all three mutant mouse lines were indistinguishable from wild-type (WT). Further, AAV (adeno-associated virus)-mediated expression of dnRab11b in retRab11a-/- retina, or expression of dnRab8b in retRab8a-/- retina did not cause OS protein mislocalization. Finally, a retRab8a-/- retina injected at one month of age with AAVs expressing dnRab11a, dnRab11b, dnRab8b, and dnRab10 (four dn viruses on Rab8a-/- background) and harvested three months later exhibited normal OS protein localization. In contrast to results obtained with dnRab GTPases in Xenopus and zebrafish, mouse Rab11a and Rab8a are dispensable for proper rhodopsin and outer segment membrane protein targeting. Absence of phenotype after expression of four dn Rab GTPases in a Rab8a-/- retina suggests that Rab8b and Rab11b paralogs maybe dispensable as well. Our data thus demonstrate significant interspecies variation in photoreceptor membrane protein and rhodopsin trafficking.

Introduction

Mammalian photoreceptors are polarized neurons, each consisting of an outer segment (OS), connecting cilium (CC), inner segment (IS), nucleus and synaptic terminal. The OS is a modified primary cilium that houses the phototransduction machinery, including the visual pigment rhodopsin, its G protein transducin, the target enzyme cGMP phosphodiesterase 6 (PDE6) and cGMP-gated channel subunits (CNG). Rhodopsin is the most abundant OS membrane protein [1]. Mature murine photoreceptors constantly renew OS membrane (~10% per day) by adding newly synthesized disk membranes at the OS base and removing old disks at the OS tip by phagocytosis [2;3]. As rhodopsin and other OS proteins are synthesized in the IS, photoreceptors require a sophisticated and highly directed trafficking pathway to compensate for OS protein turnover.

Much information concerning rhodopsin trafficking has been elucidated in leopard frog (Rana berlandieri) photoreceptors because of their large size [4;5]. Following biosynthesis and posttranslational modifications at the Golgi, rhodopsin is transported in vesicles from the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to the distal IS membrane where cargo is assembled for intraflagellar transport to the OS [6]. Rab GTPases play critical roles in guiding and docking vesicles to the target membranes. Rab proteins are small (21–25 kD), lipidated, GTP-binding and -hydrolyzing molecules present in diverse organisms from yeast to human [7]. Rab C-terminal halves contain variable regions that end with prenylation motifs signaling protein geranylgeranylation for membrane association [8]. These proteins participate in vesicular transport, docking and fusion of transport vesicles with their targets [7]. Rab8 and Rab11 each exist as two paralogs, a and b [9;10].

Rab11a and Rab8a have been shown to control rhodopsin transport in Xenopus laevis [11;12]. Budding of frog rhodopsin vesicles from TGN was suggested to be regulated by the GTPase Arf4 and its associated GAP, ASAP1 [4;13]. In this model, Rab11a is recruited to the vesicle surface by interacting with rhodopsin and ASAP1 during budding, and Rab11a reciprocally recruits Rab8a by recruiting Rabin 8, a Rab8 GEF (GDP-GTP exchange factor) [13;14]. Docking and fusion of rhodopsin vesicle at distal IS plasma membrane appears dependent on Rab8a, as transgenic expression of a dnRab8a (Rab8aT22N) causes massive rhodopsin-containing vesicle accumulation at the CC base and rapid retinal degeneration in Xenopus larva [11]. Expression of either dnRab11a or Rab11a shRNA has a similar effect in Xenopus retina [12]. Rab8 localization and Rab8 levels are often altered among various retina ciliopathies and are interpreted as a contributing factor of disease in mouse and zebrafish models [15–17]. In zebrafish, morpholino knockdown of Rab8a leads to rhodopsin mislocalization and OS shortening [15]. Rab8a has also been shown linked to intraflagellar transport in zebrafish through interacting with Rabaptin5 that interacts with IFT54 (intraflagellar transport protein 54 homolog) [18]. Notably, roles of Rab11 and Rab8 in rhodopsin transport are conserved across species. In Drosophila, Rab11 associates with rhodopsin vesicles and genetic ablation of Rab11 causes cytoplasmic accumulation of rhodopsin with failed rhabdomere morphogenesis [19], an effect that involves myosin V and an actin network [20].

In mammalian cell culture, the Rab11a-Rab8a cascade also appears to play a general role in primary ciliogenesis by delivering and docking secretory vesicles to the periciliary plasma membrane via interaction with the exocyst, as shown by disruption of Rab8a or Rab11a function by dominant negative protein expression or by RNAi knock-down [21–25]. Activated Rab8a also enters the cilium during ciliogenesis but its transport to the cilium decreases thereafter and the functional significance of Rab8-GTP in cilia is currently unknown [21;24]. In C. elegans, mutations in Rab8 suppresses formation of the membranous fans at the tip of AWB dendrite and constitutively active Rab8 results in shortened cilia, suggesting that Rab8 may inhibit cilium length but promote ciliary membrane genesis [26].

In mammals, however, the role of Rab11 and Rab8 in rhodopsin transport has not been directly tested using molecular genetics. Here we generated Rab11a KO-, Rab8a KO-, as well as Rab11a and Rab8a double KO mouse lines and found that rhodopsin and other major photo-transduction proteins traffic correctly. Further, expression of dnRab11b in Rab11a KO retina, or expression of dnRab8b in Rab8a KO retina, does not cause rhodopsin mislocalization. Simultaneously expression of dnRab8b, dnRab10, dnRab11a, and dnRab11b in retina-specific Rab8a-/- retina does not impair OS ciliary targeting of rhodopsin. These results suggest that in contrast to Xenopus and zebrafish, Rab11a and Rab8a, and likely their paralogs as well, are nonessential for targeting rhodopsin to the mouse outer segment. Further, as outer segments develop normally in Rab8a and11a GTPase mutants, Rab11a and Rab8a appear dispensable for photoreceptor ciliogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6, flippase (FLP) and EIIa-Cre transgenic mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Transgenic iCre75 were generated at the University of Utah and obtained from Dr. Ching-Kang Chen [27], HRGP-Cre from Dr. Yun Z. Le (Oklahoma Health Science Center, Oklahoma City) [28], and Six3-Cre lines from Dr. Monica Vetter (University of Utah) with permission of Dr. Furuta [29]. Mice were maintained under 12-hour cyclic dark/light conditions in standard T-cages and fed Teklad Global Soy Protein-free Extruded Rodent Diet ad libido. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and were conducted in compliance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Generation of Retina-Specific Rab11a-/- Mice

Rab11a embryonic stem (ES) cells (clone EPD0267_4_C09, C57BL/6N genetic background)) was purchased from KOMP (Knockout mouse project), the construct of which contains a gene trap (GT) cassette inserted into intron 1 and floxed exons 2 and 3 (See Fig 1A for diagram). We confirmed the gene targeting of ES cells using PCR, including 3’ and 5’ recombination arm, FRT sites and LoxP sites. ES cell blastocyst injection, generation of chimera and heterozygous (GT/+) mice was performed at the University of Utah transgenic core. Next we crossed Rab11GT/+ with flippase (FLP) mice (C57BL/6 background) to yield animals with a floxed allele (Rab11afl/+). Rab11afl/fl were crossed with Six3-Cre animals to generate retina-specific retRab11a+/- and retRab11a-/- animals. Six3-Cre animals express Cre recombinase specifically in retina (and ventral forebrain) from embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) [29]. The rd8 mutation present in Eucomm C57BL/6N ES cells was removed by outcrossing to C57BL/6J mice [30].

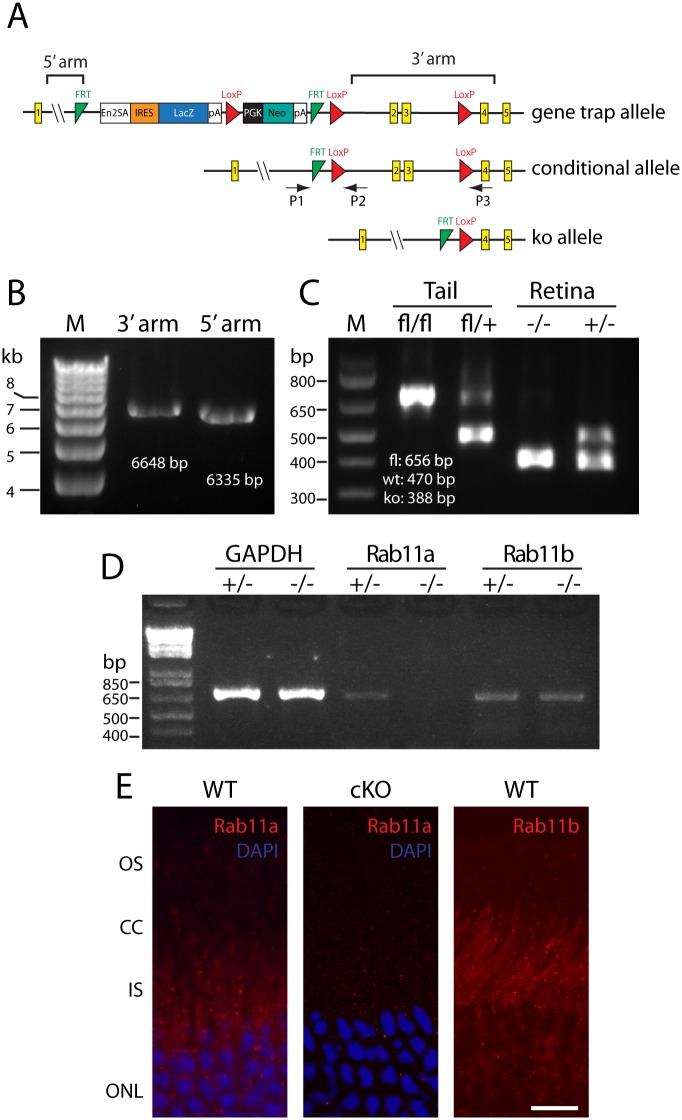

Fig 1. Generation of Rab11a retina-specific KO mouse (retRab11a-/-).

(A) Schematic of Rab11a gene-trap (GT) allele, conditional allele and KO allele. P1, P2, P3 represent primers for genotyping wild-type (WT), conditional and KO alleles. Exons are shown as yellow rectangles. The gene trap contains a splice-acceptor (SA), an IRES site, a βGeo cassette, and a poly-A site. The gene trap is flanked by two FRT sites (green triangle), a loxP site (red triangle) at the 5’-end of the cassette and another downstream in intron 3. Location of 5’-long arm and 3’-short arm are indicated. (B) Long range PCR confirmation of 3’ and 5’ recombination arm in ES cells and GT animals. (C) PCR confirms conditional deletion of exons 2 and 3 in retRab11a-/- retina but not in tail. retRab11a+/- mouse was used as control. (D) Rab11b mRNA is not up-regulated in retRab11a-/- retina. +/- and -/- refer to Rab8a heterozygous and homozygous knockouts, respectively. GAPDH was used as internal control. (E) Representative retina sections showing of Rab11a and Rab11b immunostaining in retina. Rab11a is localized mainly in punctuate IS spots in WT but is negative in retRab11a-/- KO (center). Rab11b staining pattern is similar to Rab11a (right). Scale bar, 20 μm.

Generation of Retina-Specific Rab8a-/- Mice

Sperm of Rab8afl/fl mice were provided by Dr. Akihiro Harada (Gunma University, Japan) [31]. Rab8afl/fl mice were generated by in vitro fertilization and blastocyst injection at the University of Utah Core. We subsequently generated Rab8a-/- animals by crossing Rab8afl/fl with EIIa Cre mice [32]. Rod-, cone-, and retina-specific Rab8a KOs (rodRab8a-/-, coneRab8a-/-, retRab8a-/-) were generated by crossing Rab8afl/fl with transgenic iCre75 [27], HRGP-Cre [28], and Six3-Cre lines [29].

Generation of Retina-Specific Rab11a/Rab8a Double KO Mice

Retina-specific Rab11a and Rab8a double KO mice were generated by crossing Rab11afl/fl;Rab8fl/- females with Rab11a+/-;Rab8a+/-;Six3-Cre+ males.

Electroretinography (ERG)

ERG was performed on 5 month-old (5M) retRab11a+/- and retRab11a-/- animals, 4M rodRab8a+/- and rodRab8a-/-, and 3M coneRab8a+/- and coneRab8a-/- (n = 5 each group) using an UTAS E-3000 universal electrophysiological system (LKC Technologies) as described [33]. Briefly, mice were dark-adapted overnight, anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 μg/g body weight) and xylazine (10 μg/g body weight) in 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and loaded onto recording platform with body temperature maintained at 37± 0.5°C. After dilating pupils with 1% tropicamide solution (Bausch & Lomb Inc., Tampa, FL), ERG responses were recorded from 5 mice of each genotype per time point. For scotopic ERG, mice were tested at intensities ranging from -40 decibels (db) (-3.4 log cds m–2) to 25 db (2.9 log cd s m–2). For photopic ERG, a rod saturating background light of 10 db (1.48 log cds m–2) was applied for 20 minutes before and during recording. Bactitracin ophthalmic ointment (Perrigo, Minneapolis, MN) was routinely applied to the eye to prevent infection after ERG testing, and animals were kept on heating pad until fully recovered before being returned to cages.

Confocal Immunolocalization

Eyecups were fixed by immersion in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. After cryoprotection in 30% sucrose, tissues were embedded in OCT compound and frozen on dry ice. Sections (12 μm-thick) were cut using a Micron cryostat and mounted on charged Superfrost® Plus slides (Fisher). Sections were washed in 0.1M PBS, blocked using 10% normal goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. After washes in PBS, signals were detected with Cy3 conjugated- or Alexa 488-conjuated goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Inc.) and counterstained with 1 μl/ml DAPI (4', 6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride, Invitrogen). Primary antibodies and dilutions were: mouse monoclonal anti-rhodopsin (1D4, Dr. Robert Molday, University of British Columbia), guanylate cyclase 1 (GC1) (IS4, Dr. Kris Palczewski, Case Western Reserve University), cyclic nucleotide gated channel alpha 1 and 3 (CNGA1/A3) (NeuroMab, UC Davis), synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (Vglut1) (NeuroMab, UC Davis), C-terminal-binding protein 2 (CTBP2 for Ribeye, BD Bioscience), synaptophysin (Sigma), Pan-plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases (Pan-PMCA) (5F10, Abcam), CaM kinase II (CamKII) (6G9, Abcam); rat monoclonal anti-prominin1 (Chemicon); rabbit polyclonal anti-ML- and S-opsin (Chemicon), cone transducin gamma (Cytosignal), cone arrestin, PKCα (Abcam), Calbindin (Swant), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (Covance) and choline acetyltransferase (CHAT) (Chemicon). Images were captured using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope and 60x oil lens (1.3 NA). Some images were adjusted for brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from retinas of two 5 month old retRab11a+/- and retRab11a-/- mice using Trizol reagents (Invitrogen), and reverse transcription (RT) was carried out using Superscript III first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Full length coding sequences for Rab11a and Rab11b were PCR amplified with 28 cycles. GAPDH was used as internal control (22 cycles). PCR primers used are:Rab11a-F, Rab11a-R, Rab11b-F, Rab11b-R, GAPDH-F and GAPDH-R (Table 1).

Table 1. PCR primers for Rab cDNA amplification.

| Rab11a | F | ATGGGCACCCGCGACGACG |

| R | TT AGATGTTCTGACAGCACT GCA CC | |

| Rab11b | F | ATGGGGACCCGGGACGACG |

| R | TCACAGGCTCTGGCAGCACTGCA | |

| Rab11a(S25N) | F | AATACTCGAGGCCACCATGGCATCAATGCAGAAGCTGATCTCAGAGGAGGACCTGGCTAGCGGCACCCGCGACGACGAGTA |

| R | GCGCGGATCCAGTACTTTAGATGTTCTGACAGCACTGCACC | |

| Rab11b(S25N) | F | AATAGCTAGCGGGACCCGGGACGACGAGT |

| R | TCATAGTACTTCACAGGTTCTGGCAGCACTGCAG | |

| Rab8b(T22N) | F | AATT CCGCGG ACCGGTCGCCACCATGGTGA |

| R | GTCATCTAGACTAGT GCGGTACCGTCGACTGCAGA | |

| Rab10(T23N) | F | AAGAGATCTGCAGCCGCAGCTGCACATGCGAAGAAGACGTACGACC |

| R | TACGGTCGACTCAGCAGCATTTGCTCTTCC | |

| GAPDH | F | GCCATCAACGACCCCTTCAT; |

| R | ATGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC |

Forward (F) and reverse (R) primers used to amplify Rab11a, Rab11b, dnRab11a, dnRab11b, dnRab8b, dnRab10 and Gapdh cDNA.

Generation of Dominant-Negative AAV Particles

Plasmid for each canine Rab11a(S25N)-CFP was kindly provided by Yoshiyuki Wakabayashi (NICHD, NIH), human Rab11b(S25N)-pEGFPC1 by Raymond A Frizzell (University of Pittsburgh), human Rab8b(T22N)-pEGFPC1 by Dr. Johan Peränen (University of Helsinki, Finland), and human Rab10(T23N)-EGFP-pCNA3.1 by Dr. Kenneth W. Dunn (Indiana University). Rab11a(S25N) and Rab11b(S25N) with N-terminal cMyc tags were amplified by PCR and cloned into pAAV-RK-iZsgreen shuttle vector (from Dr. Tiansen Li, NEI) using restriction sites XhoI/BamHI (Rab11a) and NheI/ScaI (Rab11b). EGFP-Rab8b(T22N), EGFP-Rab10(T23N) were PCR amplified and cloned into a modified pAAV-RK shuttle vector using SacII and XbaI (Rab8b) and BglII and SalI cloning (Rab10). All clones were verified by Sanger sequencing. PCR primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

AAV was manufactured by transfection of human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cell in culture using previously described methods [34]. Briefly, co-transfection of HEK293 cells with dnRab AAV vector plasmids and helper plasmid pXYZ5 (containing adenovirus helper genes, AAV2 Rep and AAV5 Cap) was followed harvest, then discontinuous iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation and further virus purification by FPLC. AAV vector production was performed in the Retinal Gene Therapy Vector Lab at University of Florida. Genome containing virus particles were titered by quantitative real-time PCR against a known standard and resuspended in a balanced salt solution containing 0.014% Tween-20 at a concentration of ~1.0 × 1013 vector genomes per milliliter (vg/ml). We diluted virus to 1.0 ×1012 particle per milliliter and injected 1 microliter subretinally per eye for dnRab11b or dnRab8b expression. For mixed dnRab AAV injection (dnRab11a, dnRab11b, dnRab8b and dnRab10), we mixed diluted AAV in equal volumes with total titer maintained at 1.0 ×1012 particles/ml.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± sd where n represents the number of mice analyzed. Statistical comparisons were done using one-way ANOVA for all experimental data. Differences were considered to be statistically significant for p< 0.05.

Results

Rab11a Retina Conditional Knockout Mice (retRab11a-/-)

We generated retRab11a-/- conditional knockouts using gene-trapped ES cell clones. In the Rab11a ES cell line, a gene trap (GT) cassette was inserted into intron 1 and exons 2 and 3 are flanked by loxP sites (Fig 1A). Mating with a transgenic FLP mouse line removed the GT cassette thereby generating the conditional allele. Further crossings with a Cre recombinase line under the control of a universal promoter (EIIA-Cre) [32] excised exons 2 and 3 and generated the KO allele (Fig 1A). As exons 1 and 4 are in-frame, a truncated Rab11a protein may be expressed but is predicted to be inactive and most likely degraded. We verified the gene targeting in ES cells and animals using PCR (Fig 1B). Germline deletion of Rab11a is embryonically lethal as live pups were never born (in >20 litters), as published [35]. retRab11a-/- were generated by crossing Rab11afl/fl with transgenic Six3-Cre mice which express Cre in retina starting at embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5). PCR analysis confirmed the deletion of exons 2 and 3 in retina but not in tail samples as expected (Fig 1C). At the RNA level, Rab11b mRNA expression was not upregulated In the retRab11a-/- retina (Fig 1D). Immunolocalization of Rab11a occurs predominantly in the inner segment of WT retina but is absent in the cKO retina (Fig 1E), confirming retina-specific deletion of Rab11a in retRab11a-/- mice. Antibody directed against Rab11b revealed localization in WT retina similar to Rab11a (Fig 1E).

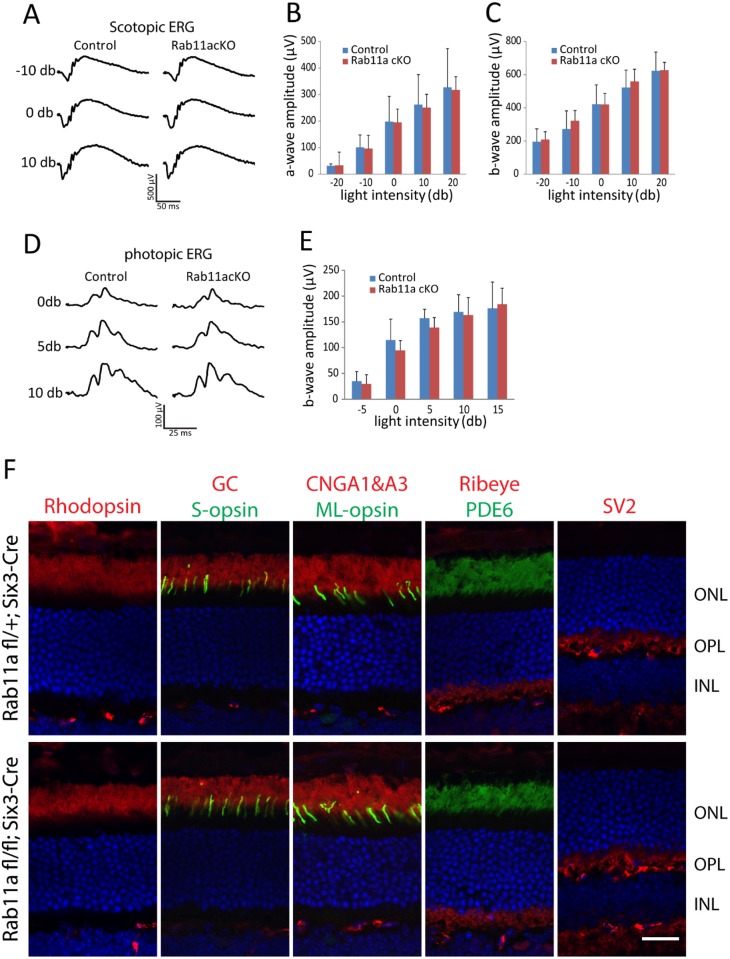

To test the functional consequence of Rab11a deletion in the retina, ERGs were measured using adult retRab11a-/- mice. retRab11a-/- scotopic ERG results of 5M animals at multiple light intensities were indistinguishable from heterozygous controls (retRab11a+/-) (Fig 2A). Minor differences of retRab11a-/- scotopic (Fig 2B and 2C) and photopic a- or b-wave amplitudes (Fig 2D and 2E) were not statistically significant. OS proteins including rhodopsin, PDE6, GC1, CNGA1/A3, S-opsin and ML-opsin, and outer plexiform layer (OPL) proteins Ribeye and SV2, localized correctly in retRab11a-/- photoreceptors (Fig 2F).

Fig 2. Electroretinography (ERG) and OS protein localization in adult retRab11a-/- mice.

(A) Representative scotopic ERG traces at -10, 0 and 10 db from 5M-old retRab11a+/- and retRab11a-/- mice. (B) and (C) Quantification of scotopic a- and b-wave amplitude at multiple light intensities. No significant difference was observed between control and KO animals (p> 0.15, n = 5 for each group, one-way ANOVA). (D) Representative photopic ERG trace at 0, 5 and 10 db from 5M-old control and KO mice. (E) Quantification of photopic b-wave amplitude at multiple light intensities. No significant difference was observed between control and KO animals (p> 0.15, n = 5 for each group, one-way ANOVA). (F) Immunostaining of rhodopsin, GC1, CNGA1/A3, PDE6, S-opsin, ML-opsin, ribeye and SV2 using 3M-old animals, showing that all proteins localize correctly in KO as in heterozygous control. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Rod and Cone Opsins Target Normally to Rab11-Deficient Outer Segments

The mouse genome contains two distinct Rab11 genes expressing geranylgeranylated Rab11a and Rab11b which differ only at the C-terminal variable region (overall identity 89.9%) (Fig 3A). Absence of an observed phenotype seen in retRab11a-/- retina may be attributed to Rab11a and Rab11b redundancy. Using adeno-associated virus (AAV), we expressed in retRab11a-/- retina a cMyc-tagged dnRab11b (Rab11b(S25N)), which is inactive and locked in the GDP form [36–38]. cMyc-Rab11b(S25N)-AAV was injected subretinally in 4M-old retRab11a-/- mice and heterozygous controls, and retinas were harvested two months post-injection. Presence of the reporter zsGreen, co-expressed with cMyc-Rab11b(S25N)-AAV, verified successful expression of the vector (Fig 3B). Rhodopsin, PDE6, GC1, CNGA1/A3, ML-opsin, S-opsin and OPL marker SV2 localized correctly in retRab11a-/- retina (Fig 3B) suggesting that Rab11a and 11b are dispensable for rhodopsin and OS protein targeting in mouse. We noticed that in contrast to endogenous Rab11b (Fig 1D), cMyc-Rab11b(S25N) (Fig 3B) and cMyc-Rab11a(S25N) (not shown) enter the OS, consistent with Rab11-GDP localization in Xenopus photoreceptor cells [12].

Fig 3. OS protein localization in adult retRab11a-/- mice injected with Rab11b(S25N) AAV.

(A) Alignment of Rab11a and Rab11b protein sequences. One critical GTP binding domain is located in exon 2. Position of S25 in Rab11b is indicated in Rab11b. Both proteins contain geranylgeranylation motifs at the C-terminus. (B) Immunostaining results show that cMyc-Rab11b(S25N) localizes mainly at IS and OS (red channel, top left panel). Rhodopsin, PDE6, GC1, CNGA1/A3, ML- and S-opsin localize correctly to OS, and SV2 localizes correctly to the OPL. Green channel in all panels detect szGreen fluorescence. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Rod- and Cone-Specific Rab8a Knockout Mice

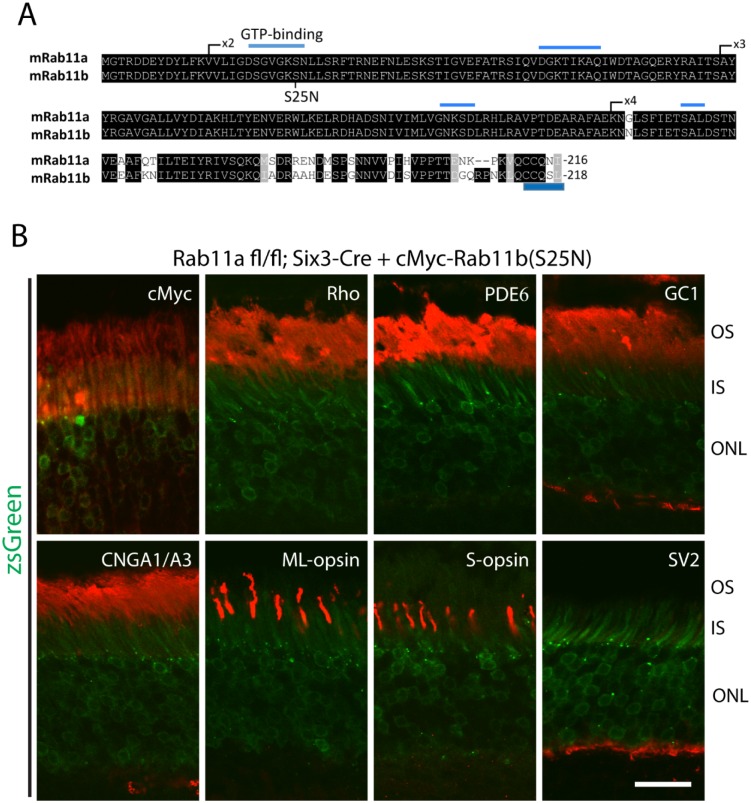

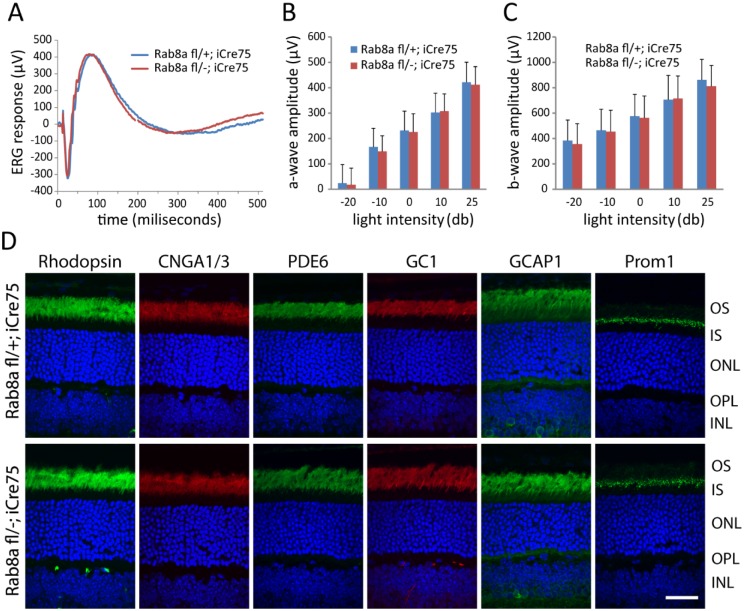

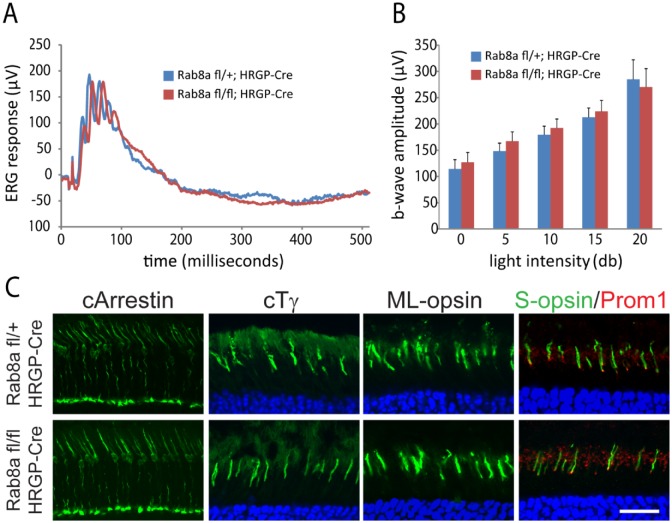

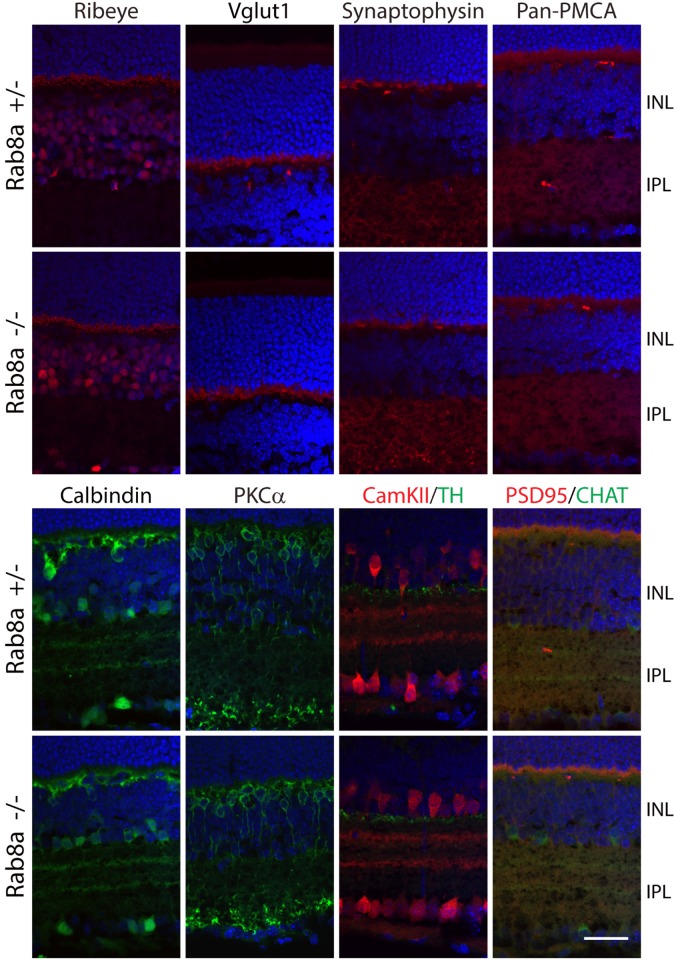

A germline Rab8a knockout demonstrated that Rab8a, necessary for the apical protein localization and nutrient absorption in the small intestine, may participate in trafficking [31]. Rab8afl/fl mice obtained from Dr. Sato contain loxP sites in intron 1 and intron 2. Breeding with EIIA-Cre mice generated germline Rab8a knockouts (Rab8a-/-) in which exon 2 was deleted truncating Rab8a after exon 1 (exon 3 is out-of-frame with exon 1). Unfortunately, Rab8a-/- mice died postnatally before reaching 1M due to intestinal microvillus defects [31]. ERG recordings of P16-P21 Rab8a-/- mice appeared normal (results not shown). To enable tests for retina function in older mice, we generated rod-specific (rodRab8a-/-) and cone-specific knockouts (coneRab8a-/-) (see Methods). Scotopic ERG of rodRab8a-/- and rodRab8a+/- mice at various light intensities at 4M produced statistically identical responses (Fig 4A–4C). Similarly, photopic ERGs are indistinguishable from controls in 3M-old coneRab8a-/- mice (Fig 5A and 5B). Rhodopsin, CNGA1/A3, PDE6, GC1, GCAP1, Prom1 in rodRab8a-/- (Fig 4D) and cone Tγ, ML-opsin, and S-opsin in coneRab8a-/- photoreceptors (Fig 5C) targeted normally to outer segments. Moreover, OPL proteins synaptophysin (SV2), Ribeye, pan-PMCA and Vglut1 as well as inner retina marker proteins PKCα, calbindin, tyrosine hydroxylase and choline acetyltransferase localized normally in Rab8a-/- retinas (Fig 6).

Fig 4. Normal ERG and rhodopsin localization in adult rodRab8a-/- animals.

(A) Representative scotopic ERG trace at 10 db from 4M-old rodRab8a+/- and rodRab8a-/- mice. (B) and (C), Quantification of scotopic a-wave and b-wave amplitudes at multiple light intensities. No significant difference was observed between control and KO animals (p> 0.17, n = 5 for each group, one-way ANOVA). (D), Immunostaining of rhodopsin, PDE6, GC1, CNGA1/A3, GCAP1 and prominin. All proteins localize correctly to OS. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Fig 5. Normal ERG and opsin localization in adult coneRab8a-/- animals.

(A) Representative photopic ERG trace at 15 db from 3M-old coneRab8a+/- and coneRab8a-/- mice. (B) Quantification of photopic b-wave amplitude at multiple light intensities. No significant difference was observed between control and KO animals (p> 0.17, n = 5 for each group, one-way ANOVA). C, Immunostaining results showed that cone arrestin, cone transducin gamma, ML-opsin, S-opsin and prominin1 all localize correctly in KO as in control. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Fig 6. Correct localizations of OPL and inner retina proteins in Rab8a global KO mice.

Immunostaining results showed that distribution of OPL proteins ribeye, Vglut1, synaptophysin, ribeye and pan-PMCA, as well as inner retina marker PKCα, calbindin, CaM kinase II (CamKII), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and choline acetyltransferase (CHAT), is indistinguishable between P21 Rab8a+/- and Rab8a -/- controls. Scale bar, 30 μm.

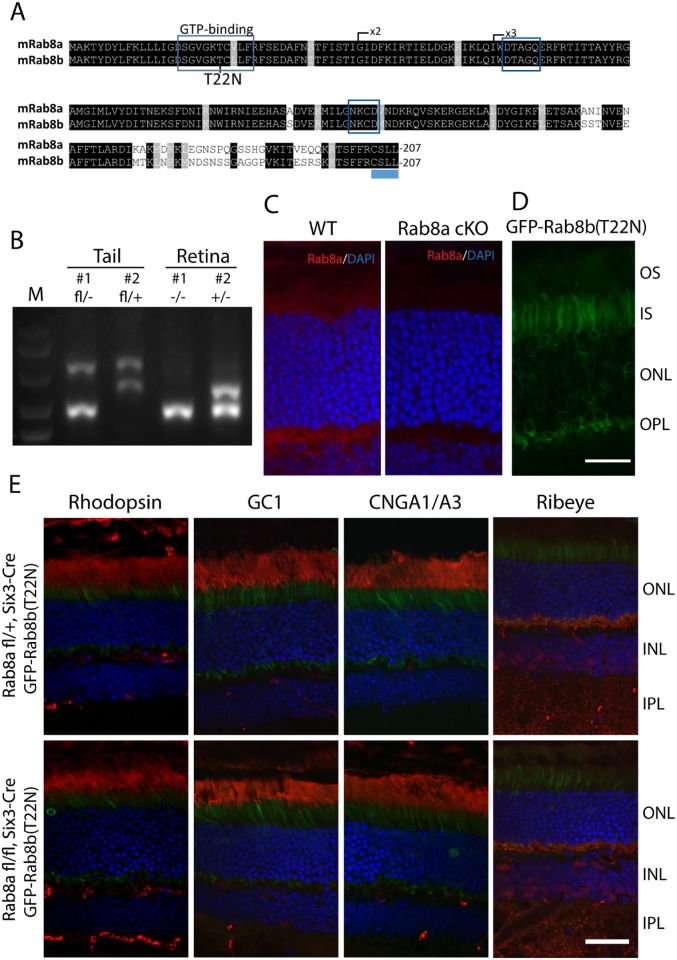

Rab8a- and Rab8b-Deficient Outer Segments Are Indistinguishable from WT

The Rab8 paralogs, Rab8a and Rab8b, are 83.6% identical (Fig 7A). As shown for Rab11, we expressed GFP-fused GDP-locked Rab8b(T22N) [39;40] virally on a retina-specific Rab8a knockout background. retRab8a-/- were generated by crossing Rab8aflfl- with Six3-Cre mice (see Methods) [29]. Genotyping confirmed deletion of exon 2 in retRab8a-/- retina but not in tail tissues (Fig 7B). Rab8a mainly localized as punctate spots in IS and OPL in WT photoreceptor cells but was absent in retRab8a-/- photoreceptors (Fig 7C). GFP-Rab8b(T22N)-AAV was injected subretinally in 4M-old retRab8a-/- and control retRab8a+/- mice. We found that different from cMyc-Rab11b(S25N) and Rab11a(S25N) (Fig 3), GFP-Rab8b(T22N) is concentrated in the IS and is absent in the OS in adult photoreceptors (Fig 7D). Two months post-injection, retRab8a-/- and retRab8a+/- retinas were harvested to investigate OS protein localization. Rhodopsin, GC1, CNGA1/A3 and Ribeye distributed normally in Rab8b(T22N)-injected retRab8a-/- mice (Fig 7E) indicating that Rab8a and Rab8b are dispensable for transport of phototransduction and synaptic membrane proteins.

Fig 7. Rhodopsin localizes normally in adult Rab8a KO mice injected with Rab8b(T22N) AAV.

(A) Alignment of Rab8a and Rab8b amino acid sequences. Exon 1 contains the GTP binding domain. Exon 2 is deleted in the germline and conditional knockouts. T22, preventing GTP binding when mutated, is shown. (B) Genotyping confirms deletion of exon2 in retRab8a-/- retinas but not tails. retRab8a+/- tissues were used as controls. (C) Immunofluorescence showed that Rab8a is mainly localized as punctate signal in IS and OPL in WT but absent in retRab8a-/- photoreceptor cells. (D) Rab8b(T22N) is mainly localized at IS and OPL. (E) Rhodopsin, GC1, CNGA1/A3 and ribeye are localized correctly in 4M-old retRab8a-/- and retRab8a+/- animals injected with dnRab8b (Rab8b(T22N)) AAV. Scale bars, 20 μm (C and D) and 30 μm (E).

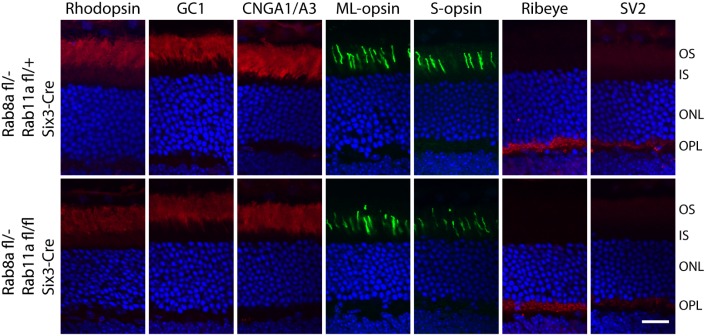

Normal Rhodopsin Localization in Rab11a/Rab8a Double Knockout Mouse

Apart from the Rab11-Rabin8-Rab8 cascade, Rab11 and Rab8 also share downstream effector proteins including the exocyst subunit Sec15 [41;42] and the molecular motor myosin Vb [43;44], suggesting there may be a possible functional redundancy between Rab11a and Rab8a polypeptides. We therefore generated retRab8a-/-retRab11a-/- double knockout mice and checked rhodopsin distribution. Again, rhodopsin and other transmembrane proteins destined for OS or synaptic terminals (GC1, CNGA1/A3, ML-opsin, S-opsin, Ribeye and SV2) localized correctly in the Rab11a;Rab8a dKOs (Fig 8).

Fig 8. Rhodopsin localizes normally in adult Rab11a and Rab8a double KO mice.

Immunostaining of rhodopsin, GC1, CNGA1/A3, PDE6, ML-opsin, S-opsin, ribeye and SV2 using 3M-old animals showed that all proteins localize correctly in dKOs (retRab8a-/-; retRab11a-/-) as in controls (retRab8a+/-; retRab11a-/-). Scale bar, 20 μm.

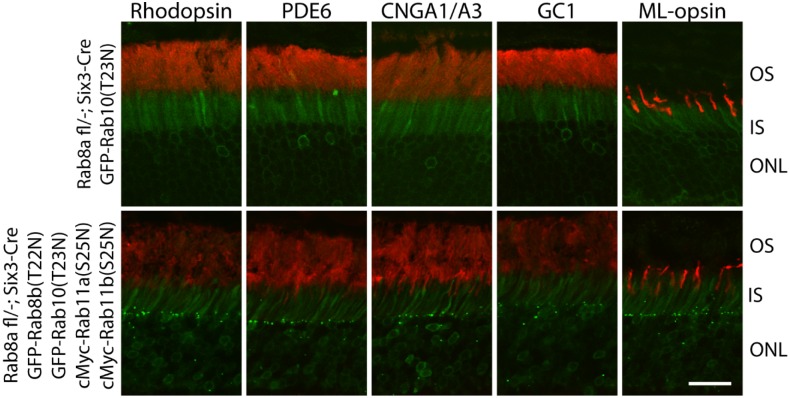

Expression of GFP-Rab8b(T22N), GFP-Rab10(T23N), cMyc-Rab11a(S25N) and cMyc-Rab11b(S25N) in Rab8a KO Retina Do Not Impair Rhodopsin OS Targeting

As a final attempt to exclude redundancy between Rab11 and Rab8 polypeptides, we simultaneously expressed GFP- or cMyc-tagged Rab8b(T22N), Rab10(T23N), Rab11a(S25N), Rab11b(S25N) on the retRab8a-/- background. Rab8b(T22N) and Rab10(T23N) were GFP-tagged, and Rab11a(S25N) and Rab11b(S25N) were cMyc tagged. Rab10 was chosen because it is the closest relative of Rab8 by sequence within the Rab8 subfamily [45]. Similar to GFP-Rab8b(T22N) (Fig 7), GFP-Rab10(T23N) mainly localized at the IS and OPL (Fig 9). Three months after subretinal AAV injection into 1M-old retRab8a-/- mice, we found that OS proteins (rhodopsin, PDE6, GC1, CNGA1/A3, ML-Opsin) localized correctly in 4 dnRabs-injected or dnRab10 only-injected animals (Fig 9). These results suggest that members of Rab8 and Rab11 families are dispensable for rhodopsin transport to the OS.

Fig 9. Rhodopsin correctly targets to the OS in adult Rab8a retina cKO mice injected with GFP-Rab8b(T22N), GFP-Rab10(T23N), cMyc-Rab11a(S25N) and cMYc-Rab11b(S25N) AAV.

One month old retRab8a-/- mice were injected subretinally with mixed Rab11a(S25N), 11b(S25N), 8b(T22N) and 10(T23N) AAVs or Rab10(T23N) only-AAV. Three months post-injection, rhodopsin, PDE6, GC1, CNGA1/A3 and ML-opsin all localize correctly in injected animals. Scale bar, 30 μm.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that Rab8a and Rab11a are dispensable for mouse photoreceptor ciliogenesis and rhodopsin OS targeting. All tested genetic deletions and disruptions (retRab8a-/-, retRab11a-/-, retRab8a/11a dKO, retRab8a-/-;dnRab8b, retRab11a-/-;dnRab11b, and retRab8a-/- with 4 dnRabs) had no obvious effect on rhodopsin or other phototransduction and synaptic membrane protein distribution, outer segment or synapse formation, or photoreceptor function. Our Rab8a/b knockout results are consistent with a recently generated Rab8a/8b dKO mouse that shows normal OS ultrastructure [46].

Previous work in frog photoreceptor cells [4;5;47–50] suggested that Rab8a and Rab11a interact directly with rhodopsin [12;14] and are components of the rhodopsin ciliary targeting complex which includes ASAP1 (ArfGAP with SH3 Domain, Ankyrin Repeat And PH Domain 1), Rab11a, Rab11 FIP3 (Rab11 family interacting protein 3), Rabin8 (GEF of Rab8) and Rab8a. During ciliary targeting, activation of Rab8a is thought to promote docking of rhodopsin-laden vesicles and their fusion to the plasma membrane at the periciliary ridge membrane. This model was supported by the observation of massive rhodopsin vesicle accumulation at CC base and faster photoreceptor degeneration in dnRab8a transgenic Xenopus and similar but milder rhodopsin mislocalization and photoreceptor degeneration phenotype in Rab11a shRNA or dnRab11a transgenic Xenopus [11;12]. Our finding that Rab11a and Rab8a, and likely their paralogs as well, are dispensable for rhodopsin OS targeting, photoreceptor ciliogenesis, and disk morphogenesis in mouse photoreceptors therefore is unexpected, but based on solid experimentation and mouse genetics.

There are several possible explanations for these interspecies discrepancies. First, the morphology of frog and mouse photoreceptors may contribute to the development of distinct rhodopsin ciliary targeting pathways. The frog rod outer segment has a much larger OS volume than mouse (~40x) and roughly 10 times more rhodopsin must be synthesized and delivered in frog rods than in mouse (700 vs. 80 molecules rhodopsin trafficking through the connecting cilium/second) [6]. It is possible that Rab11a and Rab8a are required for efficient rhodopsin transport in frog, while mouse photoreceptor cells may be able to tolerate the absence of Rab8a and Rab11a. Supporting this hypothesis, endogenous Rab8a, Rab11a or transgenic Rab8a-GFP, Rab11a-GFP are concentrated at the ciliary base as bright spots in frog photoreceptors [11;12;49], while in mouse Rab8a and Rab11a are dispersed throughout IS (Figs 1D and 7C). The absence of phenotype in Rab8a and Rab11a knockouts suggests that there may be other Rab proteins that are able to mediate rhodopsin vesicle docking and fusion (Rab redundancy). Redundancy does not originate from Rab11b and Rab8b/10, as dnRab11a in Rab11a KO and dnRab8b/10 in Rab8a KO do not cause rhodopsin mislocalization. Expression of dnRab proteins should largely, if not completely, disrupt the activity of corresponding endogenous Rab GTPase, as these constructs are effective in in vitro experiments [36–40;45] and they are expressed efficiently together with reporter genes in our high titer AAV injection (Figs 3B, 7D and 9). In vitro primary ciliogenesis assays reveal that, the phenotypes of Rab11a or Rab8a knockdowns by RNA interference only reduce the percentage of cells with intact cilia or reduce ciliary lengths [21;22;24;25]. This observation argues either that knockdowns were incomplete or that unidentified redundant Rabs partially compensate the loss of Rab11a or Rab8a in ciliary membrane trafficking. Currently, the Rab protein family comprises over 60 members (7), few of which have been investigated thoroughly using molecular genetics. To date, only mutations in Rab28 have been identified to cause human retina disease (recessive cone-rod dystrophy 18) [51;52], and defective geranylgeranylation of Rab27 was shown to be linked to choroideremia [53]. Preliminary results with a Rab28 germline knockout show that rhodopsin and OS proteins traffic normally (GY and WB, unpublished).

Alternatively, Rab8a /11a GTPases and their paralogs, may not be required at all in mouse retina for rhodopsin ciliary targeting and photoreceptor ciliogenesis. Because rhodopsin itself is a receptor for cytoplasmic dynein 1 (through binding to dynein light chain Tctex1) [54], rhodopsin vesicles have the potential of being transported from the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to the basal body by dynein motors independent of any Rab guidance since the photoreceptor microtubule track is built with the minus end anchored at the basal body, also called the microtubule organizing center [55]. Rhodopsin vesicles dissociated from the dynein complex must recruit additional proteins for plasma membrane docking and fusion to the periciliary ridge membrane. Mouse Rab8a and likely Rab8b are dispensable for docking, because Rab8a KO and expression of dnRab8b in Rab8 KO, did not cause rhodopsin accumulation in the IS, an observation consistent with ultrastructural data from Rab8a/8b double KO mouse [46]. Further, the only detectable phenotype in Rab8a/8b germline double KO mice is the disruption of apical membrane protein transport specifically in intestinal epithelial cells. Ciliogenesis in all tested organs (including retina photoreceptors) was normal [29;46], indicating that in contrast to numerous in vitro data, Rab8 is not essential for general ciliary trafficking in mouse. It will be important to generate conditional Rab11a deletion in other mouse ciliated tissues (olfactory bulb, kidney) to examine whether Rab11a is generally required for ciliogenesis and ciliary trafficking in cells other than photoreceptors.

Evidence for a direct role of Rab8a or Rab11a in rhodopsin transport in frog was solely based on overexpression of dominant-negative proteins or shRNA knockdown, but not by gene knockout [11;12]. As different Rabs could share the same Rab GDP-GTP exchange factor [56], GDP-locked dominant-negative Rab11a and Rab8a may target other Rabs through sequestering the shared GEF(s). It will be necessary to verify the rhodopsin mistrafficking phenotype in Rab8a and Rab11a loss of function Xenopus lines by deletion with CRISPR/CAS9. Similarly, it will be important to generate Rab11a/11b double KO mice to clarify unambiguously that both Rab11a and 11b are nonessential for rhodopsin OS targeting.

Our data demonstrate that Rab11a and Rab8a are dispensable for rhodopsin transport to the mouse OS. However, a role for Rab8a and Rab11a cannot be entirely excluded, as other Rab proteins may substitute (Rab redundancy), Other membrane trafficking events may depend on Rab8a and Rab11a in mouse photoreceptors but no obvious phenotype could be observed. Rab11a has been implicated in a variety of cellular trafficking pathways with well-established roles in recycling endosome-associated membrane trafficking [9;57]. Rab8a is involved in a broad membrane trafficking pathways including endocytosis-based membrane recycling and exocytosis at the cell edge [10]. Given the protein localization pattern of Rab11 and Rab8 in IS and OPL (Figs 1 and 7), we speculate that Rab11 and Rab8 may function in endosome-related protein sorting/recycling events in the the inner segment and synaptic IS and OPL regions of mouse photoreceptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yoshiyuki Wakabayashi (NICHD, NIH) for Rab11a-S25N-pEGFPC1 plasmid, Raymond A. Frizzell (University of Pittsburgh) for Rab11b-S25N-pEGFPC1 plasmid, Johan Peränen (University of Helsinki) for Rab8b-T22N-pEGFPC1 plasmid, Kenneth W. Dunn (Indiana University) for EGFP-Rab10-T23N-pCNA3.1 plasmid, Tiansen Li (National Eye Institute) for pAAV-RK-iZsgreen shuttle vector, Robert Molday (University of British Columbia, Vancouver) for rhodopsin 1D4 antibody, Dr. Kris Palczewski (Case Western Reserve University) for GC1 IS4 antibody.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the main body of the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NIH grants EY08123, EY019298 (WB); by NEI core grants EY014800 (Utah), 039003 and 021721 (UF); by an unrestricted grant to the University of Utah Department of Ophthalmology and to the University of Florida Department of Ophthalmology from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. (RPB; New York). WB is the recipient of an RPB Senior Investigator award and an RPB Nelson Trust Award.

References

- 1.Nickell S, Park PS, Baumeister W, Palczewski K. Three-dimensional architecture of murine rod outer segments determined by cryoelectron tomography. J Cell Biol 2007. June 4; 177:917–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bok D, Hall MO. The role of the pigment epithelium in the etiology of inherited retinal dystrophy in the rat. J Cell Biol 1971. June; 49:664–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RW. The renewal of photoreceptor cell outer segments. J Cell Biol 1967. April; 33:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Deretic D. Molecular complexes that direct rhodopsin transport to primary cilia. Prog Retin Eye Res 2014. January; 38:1–19. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Deretic D. The Arf and Rab11 effector FIP3 acts synergistically with ASAP1 to direct Rabin8 in ciliary receptor targeting. J Cell Sci 2015. April 1; 128:1375–85. 10.1242/jcs.162925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearring JN, Salinas RY, Baker SA, Arshavsky VY. Protein sorting, targeting and trafficking in photoreceptor cells. Prog Retin Eye Res 2013. September; 36:24–51. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009. August; 10:513–25. 10.1038/nrm2728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farnsworth CC, Seabra MC, Ericsson LH, Gelb MH, Glomset JA. Rab geranylgeranyl transferase catalyzes the geranylgeranylation of adjacent cysteines in the small GTPases Rab1A, Rab3A, and Rab5A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994. December 6; 91:11963–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welz T, Wellbourne-Wood J, Kerkhoff E. Orchestration of cell surface proteins by Rab11. Trends Cell Biol 2014. July; 24:407–15. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peranen J. Rab8 GTPase as a regulator of cell shape. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011. October; 68:527–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moritz OL, Tam BM, Hurd LL, Peranen J, Deretic D, Papermaster DS. Mutant rab8 Impairs docking and fusion of rhodopsin-bearing post-Golgi membranes and causes cell death of transgenic Xenopus rods. Mol Biol Cell 2001. August; 12:2341–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reish NJ, Boitet ER, Bales KL, Gross AK. Nucleotide bound to rab11a controls localization in rod cells but not interaction with rhodopsin. J Neurosci 2014. November 5; 34:14854–63. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1943-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazelova J, Astuto-Gribble L, Inoue H, Tam BM, Schonteich E, Prekeris R, et al. Ciliary targeting motif VxPx directs assembly of a trafficking module through Arf4. EMBO J 2009. February 4; 28:183–92. 10.1038/emboj.2008.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Morita Y, Mazelova J, Deretic D. The Arf GAP ASAP1 provides a platform to regulate Arf4- and Rab11-Rab8-mediated ciliary receptor targeting. EMBO J 2012. October 17; 31:4057–71. 10.1038/emboj.2012.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachmann-Gagescu R, Phelps IG, Stearns G, Link BA, Brockerhoff SE, Moens CB et al. The ciliopathy gene cc2d2a controls zebrafish photoreceptor outer segment development through a role in Rab8-dependent vesicle trafficking. Hum Mol Genet 2011. October 15; 20:4041–55. 10.1093/hmg/ddr332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westfall JE, Hoyt C, Liu Q, Hsiao YC, Pierce EA, Page-McCaw PS et al. Retinal degeneration and failure of photoreceptor outer segment formation in mice with targeted deletion of the Joubert syndrome gene, Ahi1. J Neurosci 2010. June 30; 30:8759–68. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5229-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murga-Zamalloa CA, Desai NJ, Hildebrandt F, Khanna H. Interaction of ciliary disease protein retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator with nephronophthisis-associated proteins in mammalian retinas. Mol Vis 2010; 16:1373–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omori Y, Zhao C, Saras A, Mukhopadhyay S, Kim W, Furukawa T et al. Elipsa is an early determinant of ciliogenesis that links the IFT particle to membrane-associated small GTPase Rab8. Nat Cell Biol 2008. April; 10:437–44. 10.1038/ncb1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satoh AK, O'Tousa JE, Ozaki K, Ready DF. Rab11 mediates post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin to the photosensitive apical membrane of Drosophila photoreceptors. Development 2005. April; 132:1487–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li BX, Satoh AK, Ready DF. Myosin V, Rab11, and dRip11 direct apical secretion and cellular morphogenesis in developing Drosophila photoreceptors. J Cell Biol 2007. May 21; 177:659–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nachury MV, Loktev AV, Zhang Q, Westlake CJ, Peranen J, Merdes A et al. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell 2007. June 15; 129:1201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knodler A, Feng S, Zhang J, Zhang X, Das A, Peranen J et al. Coordination of Rab8 and Rab11 in primary ciliogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010. April 6; 107:6346–51. 10.1073/pnas.1002401107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshimura S, Egerer J, Fuchs E, Haas AK, Barr FA. Functional dissection of Rab GTPases involved in primary cilium formation. J Cell Biol 2007. July 30; 178:363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westlake CJ, Baye LM, Nachury MV, Wright KJ, Ervin KE, Phu L et al. Primary cilia membrane assembly is initiated by Rab11 and transport protein particle II (TRAPPII) complex-dependent trafficking of Rabin8 to the centrosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011. February 15; 108:2759–64. 10.1073/pnas.1018823108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng S, Knodler A, Ren J, Zhang J, Zhang X, Hong Y et al. A Rab8 guanine nucleotide exchange factor-effector interaction network regulates primary ciliogenesis. J Biol Chem 2012. May 4; 287:15602–9. 10.1074/jbc.M111.333245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukhopadhyay S, Lu Y, Shaham S, Sengupta P. Sensory signaling-dependent remodeling of olfactory cilia architecture in C. elegans. Dev Cell 2008. May; 14:762–74. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Chen D, Sauve Y, Mc Candles J, Chen YJ, Chen C-K. Rhodopsin-iCre transgenic mouse line for Cre-mediated rod-specific gene targeting. Genesis 2005; 41:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le YZ, Ash JD, Al-Ubaidi MR, Chen Y, Ma JX, Anderson RE. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase to cone photoreceptors in transgenic mice. Mol Vis 2004. December 27; 10:1011–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furuta Y, Lagutin O, Hogan BL, Oliver GC. Retina- and ventral forebrain-specific Cre recombinase activity in transgenic mice. Genesis 2000. February; 26:130–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattapallil MJ, Wawrousek EF, Chan CC, Zhao H, Roychoudhury J, Ferguson TA et al. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012; 53:2921–7. 10.1167/iovs.12-9662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato T, Mushiake S, Kato Y, Sato K, Sato M, Takeda N et al. The Rab8 GTPase regulates apical protein localization in intestinal cells. Nature 2007. July 19; 448:366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakso M, Pichel JG, Gorman JR, Sauer B, Okamoto Y, Lee E et al. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996. June 11; 93:5860–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang L, Zhang H, Dizhoor AM, Boye SE, Hauswirth WW, Frederick JM et al. Long-term RNA interference gene therapy in a dominant retinitis pigmentosa mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011. November 8; 108:18476–81. 10.1073/pnas.1112758108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, Sakai Y, Loiler S, Fraites TJ et al. Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods 2002. October; 28:158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu S, Yehia G, Wang J, Stypulkowski E, Sakamori R, Jiang P et al. Global ablation of the mouse Rab11a gene impairs early embryogenesis and matrix metalloproteinase secretion. J Biol Chem 2014. November 14; 289:32030–43. 10.1074/jbc.M113.538223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butterworth MB, Edinger RS, Silvis MR, Gallo LI, Liang X, Apodaca G et al. Rab11b regulates the trafficking and recycling of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012. March 1; 302:F581–F590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Best JM, Foell JD, Buss CR, Delisle BP, Balijepalli RC, January CT et al. Small GTPase Rab11b regulates degradation of surface membrane L-type Cav1.2 channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011. May; 300:C1023–C1033. 10.1152/ajpcell.00288.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silvis MR, Bertrand CA, Ameen N, Golin-Bisello F, Butterworth MB, Frizzell RA et al. Rab11b regulates the apical recycling of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in polarized intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 2009. April; 20:2337–50. 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hattula K, Furuhjelm J, Arffman A, Peranen J. A Rab8-specific GDP/GTP exchange factor is involved in actin remodeling and polarized membrane transport. Mol Biol Cell 2002. September; 13:3268–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen S, Liang MC, Chia JN, Ngsee JK, Ting AE. Rab8b and its interacting partner TRIP8b are involved in regulated secretion in AtT20 cells. J Biol Chem 2001. April 20; 276:13209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo W, Roth D, Walch-Solimena C, Novick P. The exocyst is an effector for Sec4p, targeting secretory vesicles to sites of exocytosis. EMBO J 1999. February 15; 18:1071–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu S, Mehta SQ, Pichaud F, Bellen HJ, Quiocho FA. Sec15 interacts with Rab11 via a novel domain and affects Rab11 localization in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005. October; 12:879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lapierre LA, Kumar R, Hales CM, Navarre J, Bhartur SG, Burnette JO et al. Myosin vb is associated with plasma membrane recycling systems. Mol Biol Cell 2001. June; 12:1843–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roland JT, Kenworthy AK, Peranen J, Caplan S, Goldenring JR. Myosin Vb interacts with Rab8a on a tubular network containing EHD1 and EHD3. Mol Biol Cell 2007. August; 18:2828–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babbey CM, Ahktar N, Wang E, Chen CC, Grant BD, Dunn KW. Rab10 regulates membrane transport through early endosomes of polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol Biol Cell 2006. July; 17:3156–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato T, Iwano T, Kunii M, Matsuda S, Mizuguchi R, Jung Y et al. Rab8a and Rab8b are essential for several apical transport pathways but insufficient for ciliogenesis. J Cell Sci 2014. January 15; 127:422–31. 10.1242/jcs.136903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Morita Y, Mazelova J, Deretic D. The Arf GAP ASAP1 provides a platform to regulate Arf4- and Rab11-Rab8-mediated ciliary receptor targeting. EMBO J 2012. October 17; 31:4057–71. 10.1038/emboj.2012.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazelova J, Ransom N, Astuto-Gribble L, Wilson MC, Deretic D. Syntaxin 3 and SNAP-25 pairing, regulated by omega-3 docosahexaenoic acid, controls the delivery of rhodopsin for the biogenesis of cilia-derived sensory organelles, the rod outer segments. J Cell Sci 2009. June 15; 122:2003–13. 10.1242/jcs.039982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deretic D, Huber LA, Ransom N, Mancini M, Simons K, Papermaster DS. rab8 in retinal photoreceptors may participate in rhodopsin transport and in rod outer segment disk morphogenesis. J Cell Sci 1995; 108:215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deretic D, Puleo-Scheppke B, Trippe C. Cytoplasmic domain of rhodopsin is essential for post-Golgi vesicle formation in a retinal cell-free system. J Biol Chem 1996; 271:2279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roosing S, Rohrschneider K, Beryozkin A, Sharon D, Weisschuh N, Staller J et al. Mutations in RAB28, Encoding a Farnesylated Small GTPase, Are Associated with Autosomal-Recessive Cone-Rod Dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 2013. July 11; 93:110–7. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riveiro-Alvarez R, Xie YA, Lopez-Martinez MA, Gambin T, Perez-Carro R, Avila-Fernandez A et al. New mutations in the RAB28 gene in 2 Spanish families with cone-rod dystrophy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015. February; 133:133–9. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.4266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seabra MC, Ho YK, Anant JS. Deficient geranylgeranylation of Ram/Rab27 in choroideremia. J Biol Chem 1995. October 13; 270:24420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tai AW, Chuang JZ, Bode C, Wolfrum U, Sung CH. Rhodopsin's carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic tail acts as a membrane receptor for cytoplasmic dynein by binding to the dynein light chain Tctex-1. Cell 1999. June 25; 97:877–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Troutt LL, Burnside B. Microtubule polarity and distribution in teleost photoreceptors. J Neurosci 1988. July; 8:2371–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshimura S, Gerondopoulos A, Linford A, Rigden DJ, Barr FA. Family-wide characterization of the DENN domain Rab GDP-GTP exchange factors. J Cell Biol 2010. October 18; 191:367–81. 10.1083/jcb.201008051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelly EE, Horgan CP, McCaffrey MW. Rab11 proteins in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans 2012. December 1; 40:1360–7. 10.1042/BST20120157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the main body of the paper.