Abstract

Background

Critical illness is associated with psychological distress among family members of patients regardless of patient survival status. Factors that might contribute to successful coping among family of ICU patients have received limited investigation, most of which has focused on end-of-life care.

Objective

To develop and evaluate a preliminary, multi-faceted model for coping among family members of patients who survive mechanical ventilation.

Design

In this multi-center, cross-sectional survey, we interviewed family members of mechanically ventilated patients at the time of transfer from the intensive care unit to the hospital ward. We constructed a theoretical model of coping that included characteristics attributable to family members, family-clinician rapport, and patients. We then explored relationships between coping factors and symptoms of psychological distress (anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress).

Subjects

n=56 family members of survivors of mechanical ventilation.

Measures

Psychological distress measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Post-traumatic Stress Scale (PTSS). Optimism measured using the Life Orientation Test scale, resiliency by Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), and social support using the PROMIS inventory.

Main Results

Family members had moderate levels of psychological distress with median total HADS=14 (IQR 5, 20) and PTSS =22 (IQR 15, 31). Among family member characteristics, greater optimism (p=0.001, HADS; p=0.010, PTSS) resilience (p=0.012, HADS) and social support (p=0.013, HADS) were protective against psychological distress. On the contrary, characteristics of family clinician-rapport such as communication quality and presence of conflict did not have any associations with psychological distress.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore coping as a multi-faceted construct and its relationship with family psychological outcomes among survivors of mechanical ventilation. We found certain family characteristics of coping such as optimism, resilience and social support to be associated with less psychological distress. Further research is warranted to identify potentially modifiable aspects of coping that might guide future interventions.

Keywords: Coping, optimism, psychological distress, critical illness, intensive care unit, family member of ICU patients

Introduction

The experience of critical illness often results in significant psychological symptoms for entire family units. (1) In fact, family members experience symptoms of persistent psychological distress such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress (PTS) with a prevalence that is nearly identical to patients themselves. (2) This constellation of psychological symptoms is sufficiently prevalent that it constitutes a core element of the post-intensive care syndrome-family (PICS-F). (3) There are numerous etiologies for distress in family members of critically ill patients such as disruption of their lives by the trauma of a loved one being ill, (2) the social and economic impact of staying with the patient during hospitalization, (1, 4, 5) poor quality communication, (6, 7) the emotional burden associated with surrogate decision making, (6, 7) and an uncertain future among survivors of critical illness. (8-11) Interestingly, the negative psychological impacts are similar among families regardless of whether the patient dies or survives critical illness.(12, 13)

Although some of the associations and risk factors for adverse family psychological outcomes are well described, there is limited insight into how family coping, when considered as a multi-faceted construct, might impact psychological outcomes. Qualitative studies on coping in families of ICU survivors has shown factors such as humor, spirituality, social support, communication and hope as important to coping which in turn respondents relate to life quality.(14) A recent quantitative survey from Petrinec et al (15) found that an avoidant coping style among family members of ICU patients was associated with greater post-traumatic stress. A recent pilot study among patients and family members in the clinical context of acute lung injury showed that while most patients and caregivers used adaptive coping skills infrequently as measured with a single questionnaire, it was feasible to provide coping skills training to reduce their psychological distress. (16) However, to our knowledge, coping as a multi-faceted construct including measures of family members, clinician and patient characteristics have not been explored among family of survivors of mechanical ventilation. Thus we felt it was important to develop and evaluate a novel model for coping among family members of patients that survive mechanical ventilation. We hoped to identify potentially modifiable aspects of coping that might guide future intervention studies for family centered care in the ICU.

Materials and Methods

Setting and Respondent Recruitment

We conducted a multi-center, cross-sectional, observational study of family members of patients that survived ≥48 hours of mechanical ventilation between December 2013 and August 2014 at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and Duke University. Patient criteria prompting family member screening included mechanical ventilation for greater than 48 hours and survival to ICU discharge. Inclusion criteria for family members were self-described caregiver older than 18 years who could speak and read English well enough to not require an interpreter. Exclusion criteria for patients included lack of an identified family member, hospital discharge prior to enrollment, discharge to hospice, and involvement in another ongoing ICU-based study. We screened adult ICUs (medical, surgical, neurologic, cardiac) daily at both sites. After obtaining approval from the primary physician, study staff obtained written informed consent from family members during the time of patient transfer from the ICU to the hospital ward. Institutional review board approval was obtained at both sites. Family members were compensated $10 for their effort.

Data Collection

After receiving informed consent, study staff abstracted patient electronic medical records for patient sociodemographic measures, patient diagnoses and patient clinical measures (diagnosis, chronic medical co-morbidities (Charlson index),(17) illness severity (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE II]), (18) in-hospital procedures, and discharge disposition. The family member who was the primary decision maker was interviewed in person by study staff within a day of providing informed consent to provide the family measures.

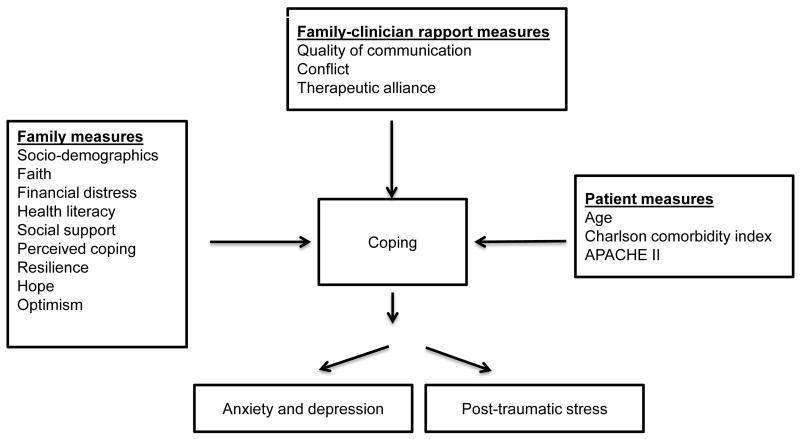

Multi-Faceted Coping Construct

We defined coping as a cognitive or behavioral effort to manage specific external or internal challenges. (19) In the setting of critical illness, we conceptualized family coping as a multi-faceted construct that is associated with a variety of factors including measures of family, family-clinician rapport and patient characteristics. We hypothesized that family member measures such as sociodemographics, faith, financial distress, health literacy, social support, quality of life and individual attributes (e.g. resilience, hope, optimism) would be associated with coping. (20-23) In addition, we hypothesized that measures of family-clinician rapport (e.g. communication quality, presence of conflict) and patient illness severity would be associated with coping.

Measures Hypothesized to be Associated with Multi-Faceted Coping Construct

Importance of faith (24) and financial distress (25) were captured on a 4-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree). Family members’ health literacy was measured using the Peterson’s 3-item scale. (26) Their perceived social support was rated on a Likert scale taken from the PROMIS inventory.(27) We measured intensity of coping using the Active Coping domain of the Brief Cope scale.(28) We used the Euro-QOL’s 100-point visual analogue scale to assess current perceived quality of life, with 0 representing the worst quality of life imaginable and 100 representing the best imaginable quality of life.(29) Resilience was assessed with the Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), (30) which includes 10 Likert-scaled items scored from 1 (not at all) to 5 (nearly all the time); scores can range from 0 (low resilience) to 40 (high resilience). The 10-item scale has been shown to be valid and internally consistent and correlates well with the original measure (r=0.92).(31) The scale also demonstrates an improvement in score with treatments aimed at increasing resilience(32). However, this scale has not been examined in the ICU setting as of yet. Hope was assessed with the Neuro-QoL item NQPPF12.(33) We measured optimism using an item from the Life Orientation Test scale which uses a five-point Likert scale.(34)

Family-clinician rapport measures included communication quality, conflict, and therapeutic alliance. Family members’ perceived quality of communication with ICU clinicians was measured using a summary item from the Quality of Communication scale, “Overall, how would you rate the ICU physician’s communication with you?”(35) To evaluate conflict, we used the 4-item version of the Decisional Conflict Scale (scores can range from 0 (conflict) to 4 (no conflict). (36) Therapeutic alliance was measured using a version of the Human Connection Scale (HCS). (37, 38) The HCS includes 15 Likert-scaled items scored from 1 (not at all/never) to 4 (a large extent/extremely); scores can range from 15 (low therapeutic alliance) to 60 (high therapeutic alliance), this measure has been shown to have concurrent validity and a high degree of internal consistency with Cronbach α = .90.(37) Family members were instructed to rate their overall impression of ICU physicians if they interacted with more than one.

Psychological Distress Outcome Measures

The study outcomes were measures of acute (i.e., in-hospital) anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms among family members of survivors of mechanical ventilation. We measured anxiety and depression symptoms using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS) which is a 14-item, 2-domain instrument with evidence of reliability (Cronbach alpha of 0.81-0.90), validity (r>0.90), and responsiveness among the critically ill and their families.(39-42) Domain scores >7 indicate either likely depression or anxiety (score range 0-42; high scores reflect greater distress) and a 5 points change on the HADS scale has been previously correlated to a clinically significant change while measuring anxiety and depression. (42, 43) The Post-traumatic Stress Scale (PTSS) is a 10-item post-traumatic stress symptoms scale that has been used frequently in the ICU context. (5, 44-48) PTSS scores ≥20 represent a risk of post-traumatic stress (score range 0-40; high scores reflect greater distress). The PTSS has excellent internal consistency (π=0.89) and test-retest reliability (ICC=0.70-0.90), evidence of concurrent validity (r=0.86), good responsiveness, and is highly sensitive (86%) and specific (62%) compared to DSM-IV criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD among ICU survivors. (5, 47, 48).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata software (College Station, TX). We imputed missing data for those who had incomplete survey items and substituted the missing item with the individual participant’s overall mean item score (not the entire population); however no single participant had more than 2 missing items for any questionnaire. We generated descriptive statistics including means, medians, and frequencies. We used Pearson’s correlations to characterize the strength of association between measures contributing to our multi-faceted coping construct and our psychological outcome measures. When we found two variables conceptually similar (e.g. hope and optimism) that had similar correlations, we used the variable potentially responsive to intervention(s). We then developed multivariable linear regression models using anxiety, depression and PTS as outcomes and included predictors that had p<0.20 in our initial tests of association. Final models were built using a stepwise linear regression process. We considered a p value < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

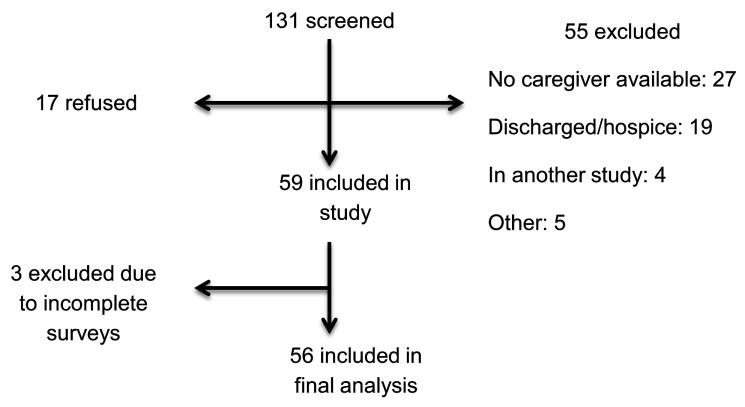

A total of 131 family members were screened, of whom 55 were excluded and 59 provided informed consent (Figure 1). Family members were predominantly female (78%) and white (57%) and their relationships to patients included spouses (32%), children (34%), and parents (18%) (Table 1). Patients were predominantly white (57%), had a high number of comorbidities (mean Charlson 2.4, SD 1.5), and a majority were treated in the medical ICU (62%) for respiratory conditions (43%) (Table 2). Patients’ mean (SD) APACHE II score was 18 (SD 5) and in-hospital mortality was 6%. Most patients (53%) were discharged home either with or without home health services.

Figure 1. Flow chart for subject accrual.

Table 1.

Patient and family socio-demographics

| Demographics | Patient n (%) n=56 | Family n (%) n=56 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| ≤45 | 12 (21) | 18 (32) |

| 46-64 | 20 (36) | 28 (50) |

| ≥65 | 24 (43) | 10 (18) |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 21 (39) | 45 (78) |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| African-American | 22 (36) | 20 (36) |

| White | 32 (57) | 32 (57) |

| Others | 4 (7) | 4 (7) |

|

| ||

| Insurance status | ||

| Medicare | 26 (46) | -- |

| Medicaid | 7 (13) | -- |

| Commercial | 12 (21) | -- |

| None | 11 (20) | -- |

|

| ||

| Religion | ||

| Catholic | 6 (11) | 5 (9) |

| Protestant | 44 (77) | 43 (75) |

| Other | 6 (12) | 8 (16) |

|

| ||

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 28 (50) | 42 (75) |

| Divorced | 9 (16) | 4 (7) |

| Single | 19 (34) | 10 (18) |

|

| ||

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 6 (11) | 30 (52) |

| Part time | 2 (4) | 5 (9) |

| Disabled | 27 (47) | 4 (7) |

| Retired | 14 (24) | 12 (21) |

| Unemployed | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

|

| ||

| Residence before ICU admission | ||

| Home | 34 (65) | |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 1 (3) | |

| Nursing facility | 2 (4) | |

| Long-term acute care | 1 (3) | |

| Other acute care hospital | 14 (27) | |

|

| ||

| Education level | ||

| <High school | -- | 4 (7) |

| High school graduate | -- | 14 (25) |

| Some college | -- | 14 (25) |

| College graduate | -- | 15 (26) |

| Advanced degree | -- | 9 (16) |

|

| ||

| Caregiver relationship to patient | ||

| Spouse | -- | 18 (32) |

| Child | -- | 19 (34) |

| Parent | -- | 10 (18) |

| Sibling | -- | 4 (7) |

| Other family | -- | 5 (9) |

Table 2.

Patient clinical characteristics

| Clinical characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Patient location, n (%) | |

| Medical ICU | 35 (62) |

| Surgical ICU | 7 (13) |

| Neurologic ICU | 11 (20) |

| Cardiac ICU | 3 (5) |

|

| |

| Admission diagnosis category, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary a | 24 (43) |

| Neurological b | 11 (20) |

| Cardiac c | 8 (14) |

| Trauma and abdominal surgery | 5 (9) |

| Infectious disease | 5 (9) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 (3) |

| Drug overdose | 1 (2) |

|

| |

| APACHE II (mean, SD)d | 18 (5) |

|

| |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ,SD)e | 2.4 (1.5) |

|

| |

| In hospital treatment/procedures, n (%) | |

| Surgery | 18 (32) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 8 (14) |

| Tracheostomy | 13 (23) |

|

| |

| Discharge Status, n (%) | |

| In-hospital mortality | 4 (6) |

| Home without home health services | 13 (23) |

| Home with home health services | 16 (30) |

| Skilled nursing facility/LTAC f/rehabilitation | 23 (41) |

Acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, other pulmonary diseases

Cerebrovascular accident, seizures, meningitis

Congestive heart failure / arrhythmia/cardiac surgery/post cardiac arrest

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (Range-0-71)

Charlson comorbidity index (Range 1-6)

Long term care facility

(Figure 2) shows the theoretical model of multi-faceted coping and the hypothesized relationships between family, family clinician rapport and patient factors we believed would be associated with family psychological outcomes. In general, the family members felt a moderate amount of financial distress though reported high levels of faith, health literacy, social support and quality of life (Table 3). In addition they reported actively coping with the family members’ illness with high levels of optimism and resilience. A moderate level of psychological distress was reflected by questionnaire scores including: HADS total (median 14; IQR 5, 20), HADS anxiety (median 7; IQR 4, 12), HADS depression (median 5; IQR 1, 8) and PTSS (median 22; IQR 15, 31). Family-clinician rapport was generally positive with high ratings of communication, therapeutic alliance and low conflict.

Figure 2. Conceptualized multi-faceted model for coping among family members of mechanical ventilation survivors.

It includes hypothesized family measures, family-clinician rapport measures and patient measures which in turn may affect coping and psychological outcomes (anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress).

Table 3.

Average scores and interpretation of family and family-clinician rapport measures

| Mean(SD) | Score range: directionality | |

|---|---|---|

| Family measure | ||

| Faith and/or spirituality a | 1.4 (0.7) | 1-4: lower more faith |

| Financial distress a | 2.7 (1) | 1-4: lower is less distress |

| Health literacy b | 13 (2) | 0-15: lower is worse literacy |

| Social support a | 1.5 (0.8) | 1-4: lower is more support |

| Intensity of coping c | 6 (2) | 0-8: lower is worse intensity |

| Quality of life (QOL) d | 78 (18) | 0-100: lower is worse QOL |

| Resilience e | 31 (6) | 0-40: lower is worse resilience |

| Hope f | 1.3 (0.6) | 1-4: lower is more hope |

| Optimism g | 1.6 (0.8) | 1-4: lower is more optimism |

| Family-clinician rapport measure | ||

| Quality of communication (QOC)h | 84 (16) | 0-100: lower is worse QOC |

| Conflict i | 3.6 (0.8) | 0-4: lower is worse conflict |

| Therapeutic alliance j | 52 (7.2) | 0-60: lower is worse alliance |

Likert scale

Peterson’s 3-item scale

Active coping domain of the brief cope scale

Euro QOL 100-point visual analogue scale

CD-RISC Conner-Davidson resilience scale

Neuro-QoL NQPPF12

Item from the Life Orientation test scale

summary item from the Quality of communication scale

Decisional conflict scale

Human connection scale

Family-related measures that showed significant associations with psychological symptoms are shown in Table 4. We found that family members who had lower levels of anxiety and depression also had higher levels of hope, optimism, and resilience. Similar associations were seen between post-traumatic stress symptoms and hope, optimism, and resilience. No measures related to family-clinician rapport or patients’ clinical status correlated with HADS or PTSS scores.

Table 4.

Associations between family psychological outcomes and hypothesized multi-faceted coping factors

| Psychological outcomes (r values) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HADS total | PTSS | ||

| Family measures | |||

| Caregiver age+ | -0.09 | 0.18 | |

| Importance of faith a | -0.13 | 0.13 | |

| Financial distress a | -0.25 | -0.38* | |

| Health literacy b | -0.12 | -0.12 | |

| Social support a | -0.29* | 0.11 | |

| Intensity of coping c | -0.32* | 0.12 | |

| Quality of life d | -0.00 | -0.44* | |

| Resilience e | -0.38* | -0.27* | |

| Hope f | -0.46* | -0.40* | |

| Optimism g | -0.54* | -0.40* | |

| Family-clinician rapport measures | |||

| Quality of communication h | -0.04 | 0.03 | |

| Conflict i | -0.08 | -0.04 | |

| Therapeutic alliance j | -0.17 | -0.03 | |

| Patient measures | |||

| Patient age+ | -0.19 | -0.13 | |

| Charlson comorbidity index k | -0.07 | -0.06 | |

| APACHE II l | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

p<0.05 by Pearson’s correlation

HADS = Hospital anxiety and depression scale; PTSS = Post-traumatic stress scale

Age measured as a continuous variable

Likert scale

Peterson’s 3-item scale

Active coping domain of the brief cope

Euro QOL 100-point visual analogue scale

CD-RISC Conner-Davidson resilience scale

Neuro-QoL NQPPF12

Item from the Life orientation test scale

summary item from the Quality of communication scale

Decisional conflict scale

Human connection Scale

Charlson comorbidity index (Range 1-6)

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (Range-0-71)

Separate linear regression models were constructed for the family psychological outcomes and are shown in Table 5. Optimism was noted to be a significant in all four of the models and was associated with lower levels of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress (all p <0.05). Noteworthy variables that were not included in final models included faith, hope, quality of communication, conflict and therapeutic alliance as they all had a p>0.20.

Table 5.

Regression models of psychological outcomes and family, family-clinician and patient measures

| Psychological outcomes | β (95% confidence interval) | p |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| HADS total | ||

| Social support a | -4.87(-8.69,-1.05) | 0.013 |

| Intensity of coping b | -4.29(-0.19,-8.39) | 0.040 |

| Resilience c | -4.82(-8.53,-1.11) | 0.012 |

| Optimism d | -3.80(-1.63,-5.96) | 0.001 |

|

| ||

| HADS anxiety | ||

| Resilience | -3.11(-5.28,-0.94) | 0.006 |

| Optimism | -2.39 (-1.15,-3.62) | 0.000 |

| APACHE II e | 2.84(0.71,4.98) | 0.010 |

|

| ||

| HADS depression | ||

| Social support | -2.59(-4.80,-0.37) | 0.023 |

| Optimism | -2.26(-1.04,-3.47) | 0.000 |

|

| ||

| PTSS | ||

| Financial distress f | 8.66(3.17,14.14) | 0.003 |

| Optimism | -4.00(-0.98,-7.01) | 0.010 |

Negative beta values are associated with less psychological distress (i.e., lower HADS and PTSS scores); positive beta values reflect greater psychological distress (i.e., higher HADS and PTSS scores) HADS = Hospital anxiety and depression scale; PTSS = Post-traumatic stress scale

Peterson’s 3-item scale

Active coping domain of the brief cope

CD-RISC Conner-Davidson resilience scale

Item from the Life orientation test scale

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (Range-0-71)

Likert scale

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to explore coping as a multi-faceted construct and its relationship with family psychological outcomes among survivors of mechanical ventilation. In general our family members reported moderate amounts of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress however; attributes such as optimism and resilience were associated with psychological coping. Additionally, better social and economic support was associated with more frequent adaptive coping behaviors, whereas measures of family-clinician rapport were not associated with coping behaviors.

In particular we found that optimism and resilience were recurring and important factors related to acute psychological distress, especially with respect to anxiety. In the context of critical illness, there is limited research on these relationships, most of which is from the perspective of prognostic discussions in which ‘being optimistic’ has been reported by family as a counterweight to poor physician prognostic estimates of survival.(49) Clinicians may understandably focus on the need to be ‘clinically realistic,’ but novel strategies to support family optimism and convey needed clinical information might help to decrease psychological stress. Such interventions would be congruent with broader psychology literature in which more optimistic people have lower levels of stress, anxiety and depression (50, 51) and in keeping with a study among trauma patients in which optimism contributed not only to coping but also to information perception and decision making. (52)

Resilience was also associated with lower rates of adverse psychological outcomes in the multivariable model. In popular culture, stories of resilience are inspiring, including Louis Zamperini a World War II prisoner of war (53) and Ernest Shackleton with his doomed voyage to Antarctica. (54) More formally, resilience has been described by the American Psychological Association as a trait that facilitates adapting or recovering from adversity. (55) Resilience in the medical literature is associated with lower rates of PTSD in parents of children with cancer (56), military recruits (57), and refugees. (58) ICU clinicians might not view surviving mechanical ventilation as a comparable story of resilience; yet, resilience as a construct offers protection against adverse psychological outcomes and hence could be a target for future, family-centered interventions. (59, 60)

We found that better social support and financial resources were associated with lower rates of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress. This is similar to findings from qualitative studies in family members of ARDS survivors. (14) Proactively screening for unmet social or financial needs might be one strategy to support family of survivors of mechanical ventilation.

Notably, our measures of family-clinician rapport were not associated with the frequency of coping behavior use or with psychological outcomes. This may be because family members had generally high ratings of communication and therapeutic alliance and reported low levels of conflict with clinicians. In prior work we found that therapeutic alliance reflects important combinations of trust, communication, and cooperation and could be an important outcome for family-centered research. (38) This may also be because all family members that we interviewed were related to survivors of mechanical ventilation and thus experienced lower rates of psychological distress as compared to end-of-life care studies that focus on communication and psychological outcomes.

We found no significant associations between measures of patient’s clinical status and psychological outcomes; except in multivariable modeling worse APACHE II scores were associated with worse caregiver anxiety. This may indirectly reflect discussions between ICU clinicians and families with more intense conversations occurring among family of more seriously ill ICU patients, although our data cannot directly address this speculation. It should also be noted that a quarter of our patients had undergone a tracheostomy and thus could be considered ‘chronically critically ill’ (61) and hence our findings may not generalize to all survivors of mechanical ventilation. In addition, the absence of information about the patient length of stay may influence psychological outcomes and should be considered as a variable in the future studies.

This study has other limitations. It characterizes perspectives from family members at two academic medical centers in the southeastern US and different findings may be reported in other geographic regions. Furthermore, we only sampled family members of patients who survived mechanical ventilation and agreed to discuss their experience with our team so there is the possibility of response bias. Although the survey instruments utilized for our outcome measures have been applied extensively in family members of ICU patients, this is a novel application of several other instruments [CD-RISC (30), HCS (37, 38), Neuro-QoL item NQPPF12 (33), Life Orientation Test scale (34)] and hence would benefit from future psychometric assessments. Since this study was survey based, the number of instruments used may have caused respondent fatigue although no participant reported any trouble understanding or completing the surveys. In addition, our study captured only family members’ perceptions and the experience of patients and ICU clinicians is an important issue for future studies. Another caveat is that we asked family to respond regarding rapport with ICU physicians and did not measure perceptions of rapport with nursing staff which should be explored in future studies. Finally, this was an exploratory study and our conceptual model of coping should be further validated before informing directionality and specific intervention strategies.

In conclusion, this is the one of the first studies to explore the association between coping as a multi-faceted construct and acute psychological distress among family members of survivors of mechanical ventilation. Family member attributes like optimism and resilience seem to decrease psychological distress and addressing practical social and financial needs might benefit with coping in family of survivors of mechanical ventilation. Ideally, coping skills training to improve psychological distress similar to what has been done in family members of acute lung injury survivors (16) should be an area of focus for enhancing family centered care and should include longitudinal follow-up.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Dr. Christopher Cox was supported by NIH grant R01 HL109823.

Copyright form disclosures: Dr. Cox received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Name of the institution: Medical University of South Carolina and Duke University

Previous presentations: Portions of this work were presented in abstract form American Thoracic Society International Conference, Denver CO 2015.

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):336–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):618–24. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook DJ, Guyatt G, Rocker G, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation directives on admission to intensive-care unit: an international observational study. Lancet. 2001;358(9297):1941–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06960-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twigg E, Humphris G, Jones C, et al. Use of a screening questionnaire for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a sample of UK ICU patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(2):202–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: a descriptive study. Heart Lung. 1979;8(2):332–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Satisfaction with communication in ICU patients and relatives: comparisons with medical staffs’ expectations and the relationship with psychological distress. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loss SH, de Oliveira RP, Maccari JG, et al. The reality of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: a multicenter study. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2015;27(1):26–35. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20150006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, et al. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(4):446–54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0210CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonsmark L, Rosendahl-Nielsen M. Experience from multidisciplinary follow-up on critically ill patients treated in an intensive care unit. Dan Med J. 2015;62(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delle Karth G, Meyer B, Bauer S, et al. Outcome and functional capacity after prolonged intensive care unit stay. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118(13-14):390–6. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0616-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAdam JL, Fontaine DK, White DB, et al. Psychological symptoms of family members of high-risk intensive care unit patients. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21(6):386–93. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012582. quiz 94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2005;20(1):90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox CE, Docherty SL, Brandon DH, et al. Surviving critical illness: acute respiratory distress syndrome as experienced by patients and their caregivers. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2702–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6f64a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrinec AB, Mazanec PM, Burant CJ, et al. Coping Strategies and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Post-ICU Family Decision Makers. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(6):1205–12. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox CE, Porter LS, Hough CL, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a telephone-based coping skills training intervention for survivors of acute lung injury and their informal caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(8):1289–97. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2567-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prouty AM, Fischer J, Purdom A, et al. Spiritual Coping: A Gateway to Enhancing Family Communication During Cancer Treatment. J Relig Health. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlrup B, Ekstrom H, Nordell E, et al. Coping as a caregiver: A question of strain and its consequences on life satisfaction and health-related quality of life. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61(2):261–70. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wartella JE, Auerbach SM, Ward KR. Emotional distress, coping and adjustment in family members of neuroscience intensive care unit patients. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(6):503–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glass Kerrie, F K, Hankin Benjamin L, Kloos Bret, Turecki Gustavo. Are Coping Strategies, Social Support, and Hope Associated With Psychological Distress Among Hurricane Katrina Survivors? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28(6):779–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plante TG, Vallaeys C, Sherman AC, Wallston KA. The development of a brief version of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire. Pastoral Psychology. 2002;50:359–68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore MJ, Zhu CW, Clipp EC. Informal costs of dementia care: estimates from the National Longitudinal Caregiver Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(4):S219–28. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305:1695–701. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawson DM. PROMIS: a new tool for the clinician scientist. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011;55(1):16–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–28. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson JR, Payne VM, Connor KM, et al. Trauma, resilience, and saliostatis: Effects of treatment on posttraumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;20(1):43–8. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuro-QoL investigators DDC. Development and Initial Validation of Patient-reported Item Banks for use in Neurological Research and Practice. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67(6):1063–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1086–98. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Legare F, Kearing S, Clay K, et al. Are you SURE?: Assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(8):e308–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the Human Connection Scale. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3302–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huff NG, Nadig N, Ford DW, et al. Therapeutic Alliance between the Caregivers of Critical Illness Survivors and Intensive Care Unit Clinicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-408OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):1893–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale--a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(1):17–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2005;20(1):90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickel M, Leiberich P, Nickel C, et al. The occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients following intensive care treatment: a cross-sectional study in a random sample. J Intensive Care Med. 2004;19(5):285–90. doi: 10.1177/0885066604267684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schelling G, Briegel J, Roozendaal B, et al. The effect of stress doses of hydrocortisone during septic shock on posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(12):978–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schelling G, Stoll C, Haller M, et al. Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(4):651–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoll C, Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HB, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a screening test to document traumatic experiences and to diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder in ARDS patients after intensive care treatment. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(7):697–704. doi: 10.1007/s001340050932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson JC, Girard TD, Gordon SM, et al. Long-term cognitive and psychological outcomes in the awakening and breathing controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):183–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0442OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zier LS, Sottile PD, Hong SY, et al. Surrogate decision makers’ interpretation of prognostic information: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):360–6. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajandram RK, Ho SM, Samman N, et al. Interaction of hope and optimism with anxiety and depression in a specific group of cancer survivors: a preliminary study. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:519. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gustavsson-Lilius M, Julkunen J, Keskivaara P, et al. Predictors of distress in cancer patients and their partners: the role of optimism in the sense of coherence construct. Psychol Health. 2012;27(2):178–95. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.484064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verhaeghe ST, van Zuuren FJ, Defloor T, et al. How does information influence hope in family members of traumatic coma patients in intensive care unit? J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(8):1488–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jolie A. Unbroken. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harland Lynn, H W, Jones James R, Reiter-Palmon Roni. Leadership Behaviors and Subordinate Resilience. Omaha: UoN, ed. Psychology Faculty Publications; 2005. Paper 62. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, et al. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eilertsen ME, Hjemdal O, Le TT, et al. Resilience factors play an important role in the mental health of parents when children survive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Acta Paediatr. 2015 doi: 10.1111/apa.13232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skomorovsky A, Stevens S. Testing a resilience model among Canadian Forces recruits. Mil Med. 2013;178(8):829–37. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ajdukovic D, Ajdukovic D, Bogic M, et al. Recovery from posttraumatic stress symptoms: a qualitative study of attributions in survivors of war. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh F. The concept of family resilience: crisis and challenge. Fam Process. 1996;35(3):261–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walsh F. Strengthening family resilience. Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carson SS. Definitions and epidemiology of the chronically critically ill. Respir Care. 2012;57(6):848–56. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01736. discussion 56-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]