Abstract

We report an active delivery mechanism targeted specifically to Gram(−) bacteria based on the photochemical release of photocaged ciprofloxacin carried by a cell wall-targeted dendrimer nanoconjugate.

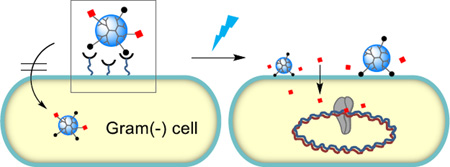

A Graphical and Textual Abstract

We report a light-controlled release mechanism for photocaged ciprofloxacin carried by a cell wall-targeted dendrimer nanoconjugate. Validation of this bacteria-targeted strategy adds a novel modality to existing light-based therapies for wound treatments.

Drug delivery for the effective treatment of bacterial infections is still an unmet need for certain localized wounds and for ocular infections.1 Poor blood perfusion to these infected sites limits the utility of oral or systemic routes of anti-infective drug administration. Additionally, the non-selective effects of certain anti-infective agents upon topical application on the wound healing process and on non-infected tissues also hinders treatment.1 Targeted delivery of antibacterial therapeutics with multifunctional nanoparticles (NPs) conjugated with bacteria-specific ligands constitutes a promising strategy for treating localized infections.2–7 However the challenge of overcoming the thick cell wall structure8 which poses a barrier to both passive and active modes of NP uptake still poses a significant hurdle to these methods for antibacterial use. Here we report a proof of concept study for a novel, stimulus-controlled delivery strategy in bacteria that enables light triggered, targeted release of an antimicrobial payload at the bacterial cell wall surface.

Multivalent strategies9–12 have played a fundamental role in the design of NPs for the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents, genes and imaging molecules to a broad range of cell types and pathogens.13–15 In particular, multivalent attachment of bacterial cell wall or outer membrane specific ligands to NPs improved their functional activity in the detection and rapid isolation of bacterial cells, and enhanced the antimicrobial activities of NPs carrying therapeutic payloads.2, 4–7, 16, 17 We and others have reported on the specific targeting of bacteria by NPs through the multivalent conjugation of cell wall-targeting small molecule ligands including vancomycin2–5, 18 and polymyxin,16, 19 as well as cationic antimicrobial peptides.20, 21 Such multivalent NPs were shown to adsorb to the cell wall very tightly, and could be further modified with additional functionalities for fluorescence detection,3, 16 magnetic bacterial isolation4, 5, 19 and promotion of opsonisation by macrophages.18

Despite their tight and specific cell wall adsorption, most of these targeted NPs show suboptimal bactericidal activities4, 5, 16, 18 largely due to their poor intracellular uptake.8 Thus, a conjugate in which the advantages of a tightly binding delivery vehicle that acts to focus on a high local concentration of drug at the bacterial surface in combination with a mechanism that enables drug release at the bacterial surface is of high value.

Release mechanisms currently developed for nanoconjugates are largely based on reactions that occur in mammalian cells by endogenous factors such as low pH in endosomes,22 differences in intracellular and extracellular thiol/disulfide redox potential,23 and hydrolytic enzymes24 in lysosomes.25 These mechanisms are not directly applicable to antibiotic delivery due to their irrelevance to bacterial systems and to the poor uptake of NPs in bacteria. Use of UV light has been well validated for various controlled-release applications including the spatiotemporal control of gene expression in vivo,26 and tumor targeted drug delivery.25, 27, 28 Further, light only-based therapies which include photodynamic therapy and UVB (280–315 nm) irradiation are already in use clinically as alternative antibacterial therapies.29, 30 In the present study, we expand the scope of light-based therapy by combining the functionalities of light-controlled release of an antibiotic payload with the specificity of bacterial cell wall targeting on the same NP. This nanoconjugate could potentially augment current photodynamic therapy regimens.

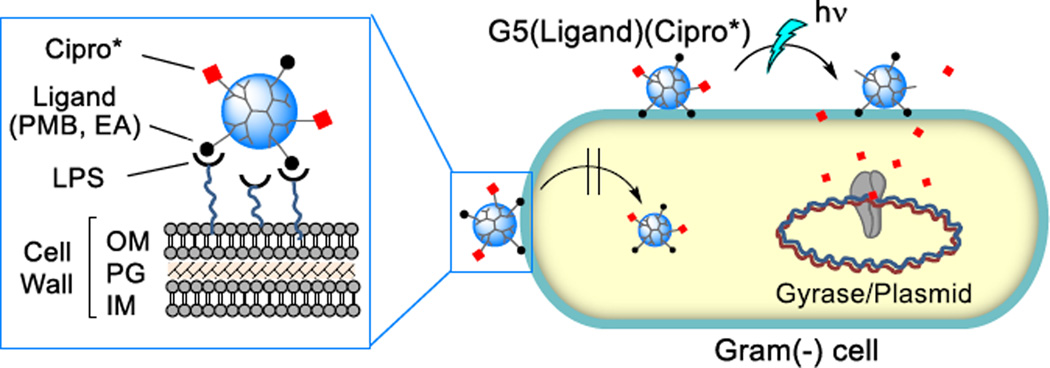

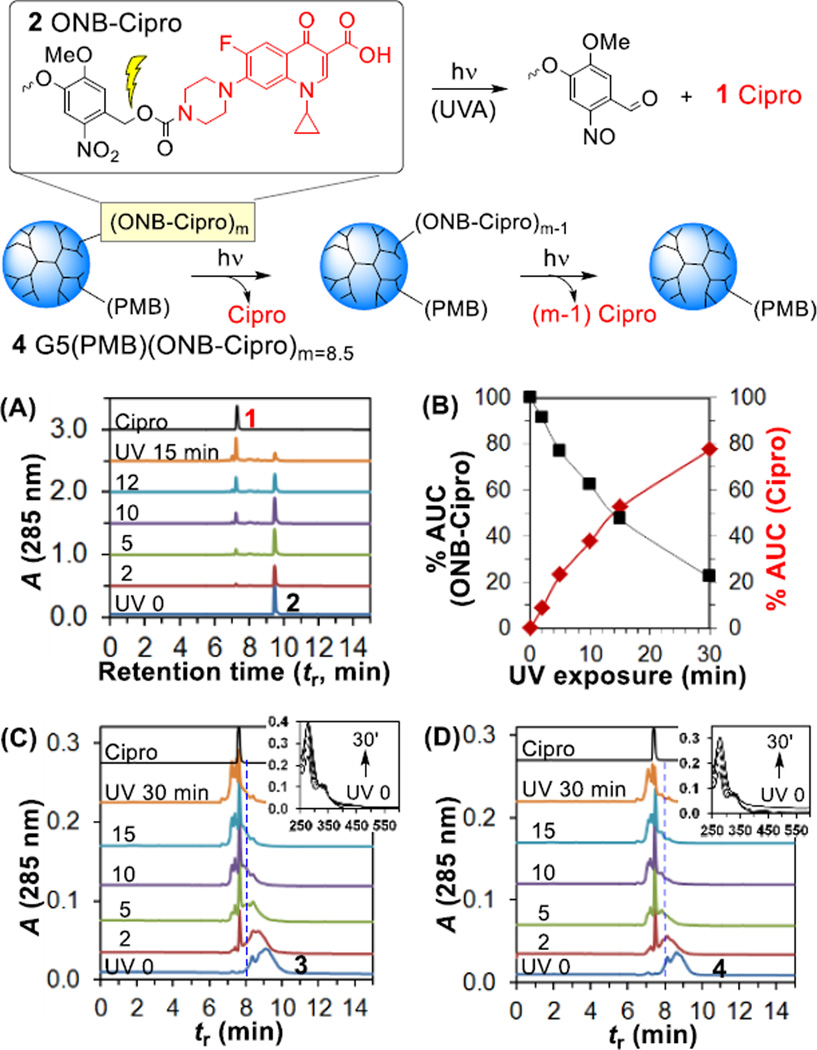

Photocaged ciprofloxacin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, was attached to a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimer nanoconjugate for cell wall targeted delivery (Fig. 1). The delivery system was designed using a fifth generation (G5) PAMAM31 dendrimer parent, conjugated with excess outer-membrane targeted ligands, polymyxin B (PMB, a polycationic cyclic peptide) or a PMB-mimicking molecule, ethanolamine (EA) as the carrier for 1 ciprofloxacin (Cipro), an inhibitor of DNA gyrase (Fig. 2). Use of these ligands with the dendrimer system for bacterial targeting has been validated in our previous study16 which demonstrated their tight and specific adsorption to a model surface immobilized with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (KD = 2.1–1.4 nM)16 and to E. coli cells in vitro. First, an N-Boc protected form of 2 ONB-Cipro was synthesized by derivatization of ciprofloxacin at the secondary amine through a carbamate bond with a photocleavable ortho-nitrobenzyl (ONB) linker32–35 (Scheme S1) and its structural identity was characterized by ESI mass spectrometry (HRMS: calcd for C35H42FN6O12 [M+H]+ 757.2839, found 757.2844), UV–vis absorption (λmax = 340 nm, ε = 3101 M−1cm−1; 271 nm, ε = 7679 M−1cm−1) and 1H NMR (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Scheme for light-controlled, targeted delivery of photocaged ciprofloxacin (Cipro*) carried by a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding dendrimer G5(Ligand)(Cipro*) adsorbed to the outer membrane (OM) of the Gram(−) cell wall. Internalized Cipro inhibits DNA gyrase. Abbreviations: PMB = polymyxin B; EA = ethanolamine, a PMB-mimicking lower affinity but more biocompatible ligand; PG = peptidoglycan; IM = inner membrane.

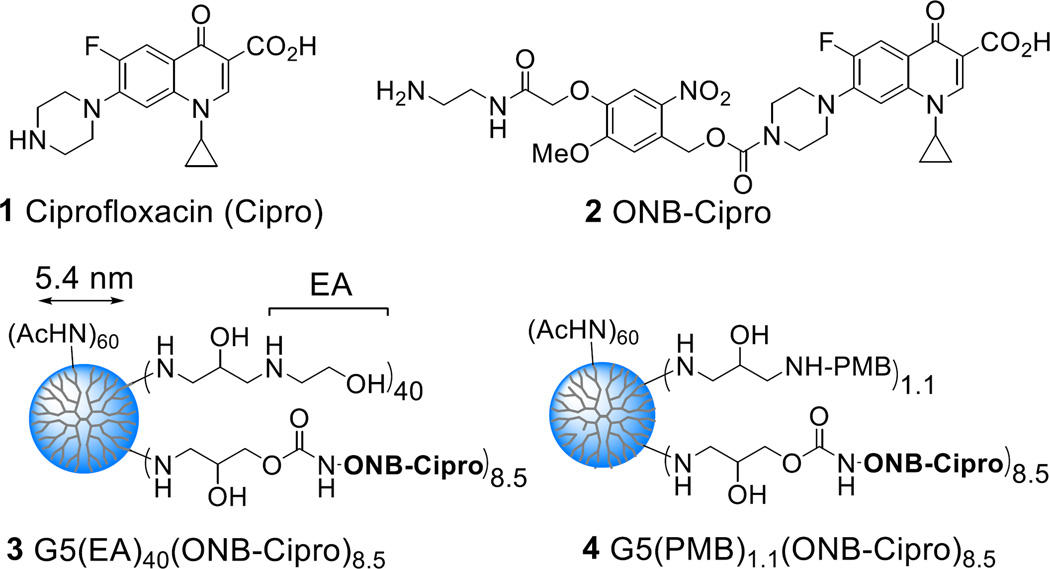

Fig. 2.

Structure of ciprofloxacin, photocaged ciprofloxacin (ONB-Cipro), and G5 PAMAM dendrimers 3–4 conjugated with ONB-Cipro and a cell wall targeting ligand (L) such as ethanolamine (EA) (3) or polymyxin B (PMB) (4).

2 ONB-Cipro was modified at its amine terminus by attachment of an oxirane group (Scheme S2) which allowed covalent coupling to partially acetylated (Ac)60G5(NH2) dendrimer derived from G5(NH2)114 (Mw = 26,600 gmol−1, polydispersity index (PDI) = Mw/Mn ~1.010)36 (Scheme S3). The remaining primary amines of the resulting dendrimer were capped with epibromohydrin for ligand conjugation with excess ethanolamine (EA) and PMB which yielded conjugates 3 G5(EA)n(ONB-Cipro)m (n = 40; m = 8.5) and 4 G5(PMB)n(ONB-Cipro)m (n = 1.1; m = 8.5). After purification by membrane dialysis (MWCO 10 kDa), each conjugate was fully characterized for its polymer purity (UPLC; >95%), molar mass (MALDI-TOF: Mr = 31,300 (3), 31,500 (4) gmol−1), and UV–vis absorption (ONB-Cipro: λmax (3) = 337 nm (ε = 3,315 M−1cm−1); λmax (4) = 335 nm (ε = 3,857 M−1cm−1) in PBS, pH 7.4) as summarized in the Supplementary Information. The valency of attached ONB-Cipro (m) and PMB (n) on 3 and 4 was determined on an average basis by UV–vis analysis (m = 8.5 (mean), and 9 (median) by Poisson distribution,37 Fig. S5) and by NMR integration (n = 1.1).16 Further characterization by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) led to the determination of their polymer distribution (PDI = 1.081 (3), 1.131 (4)). The basis for such increased dispersity after drug conjugation is partially attributable to the distribution of ONB-Cipro molecules attached to the dendrimer (Fig. S5). Hydrodynamic size (Zave) and zeta potential (ZP) measurements of 3 and 4 (Table S2) suggest that these conjugates are more cationic than unmodified G5(NH2)114 as expected for conjugation with the cationic EA residues, and tend to form smaller aggregates upon co-conjugation with ONB-Cipro.

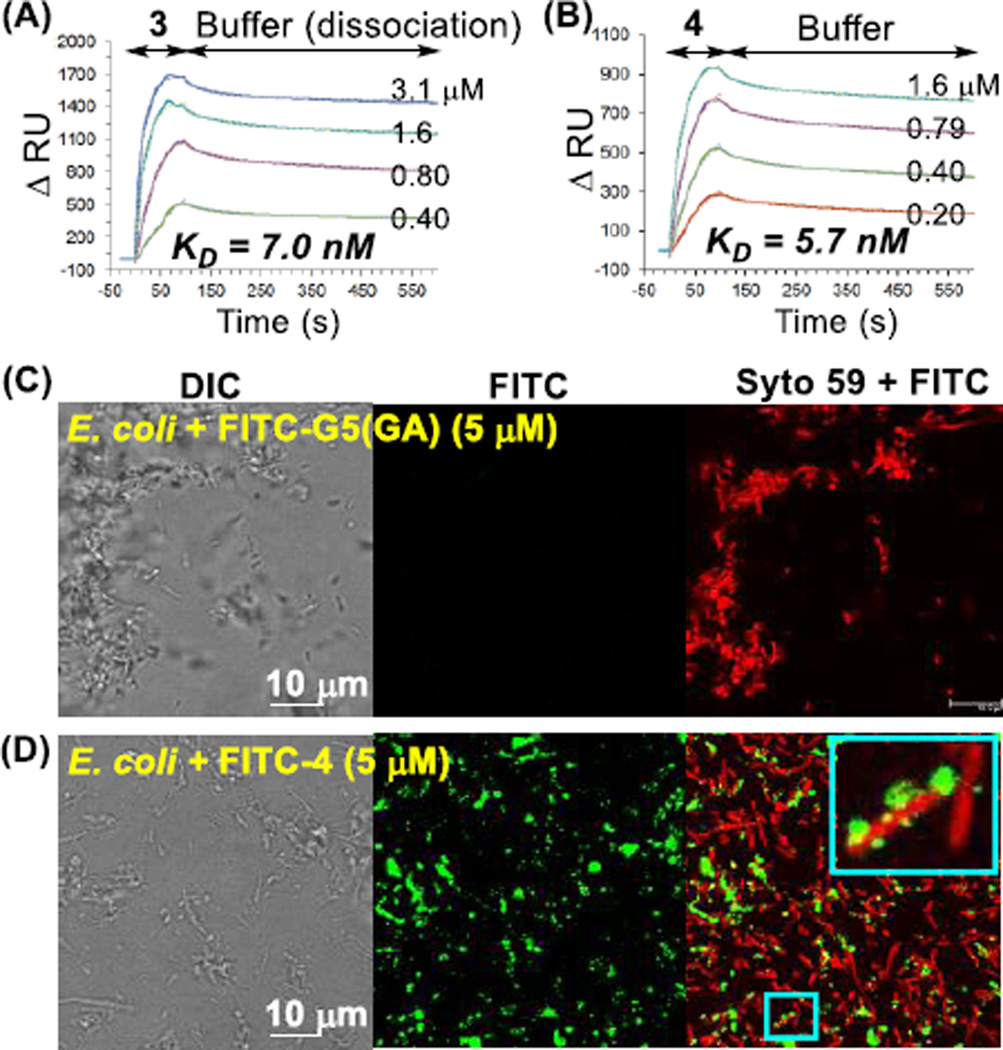

The binding avidity of these two conjugates to the bacterial surface was evaluated with a Gram(−) cell wall model by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy as described previously.4, 16 Each conjugate showed tight binding to the sensor chip surface containing immobilized LPS in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). Sensorgram kinetic analysis showed markedly slow dissociation rates for both dendrimers, reflecting the tight association imparted by multivalent ligand binding.9–11 Langmuir fitting analyses38 performed for each sensorgram set yielded dissociation constant (KD) values of 7.0 nM (3) and 5.7 nM (4) (KD = koff/kon; Table S3). Conjugates 3 and 4 thus bounnd tighter than free monovalent PMB (KD = 150 nM16), with a multivalent enhancement (β) factor of 21 and 26 over PMB, respectively. These values are consistent with previous results16 observed for the dendrimer modified with only PMB ligand and/or excess EA as an auxiliary ligand without the photocaged ciprofloxacin (ONB-Cipro), demonstrating that the attached ONB-Cipro does not affect the binding avidity. In addition, SPR experiments performed using a model surface for Gram(+) bacteria (immobilized with (D)-Ala-(D)-Ala) demonstrated a lack of binding by conjugate 3 or 4, supporting their LPS-targeting specificity (Fig. S6).

Fig. 3.

(A, B) Overlaid SPR sensorgrams of 3 G5(EA)40(ONB-Cipro)8.5 and 4 G5(PMB)1.1(ONB-Cipro)8.5 binding to a LPS-immobilized cell wall model surface. Experimental (solid line); simulated global fit (dotted line). (C, D) Confocal fluorescence images of E. coli treated with the control dendrimer FITC-G5(GA)16 (C) or with FITC-4 G5(PMB)1.1(ONB-Cipro)8.5 (D). Inset: an enlarged view. FITC fluorescence is shown (green). Bacterial cells were also stained with SYTO59 (red).

We investigated the binding of fluorescein 5(6)-isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled conjugate 4 to Escherichia coli (XL-1) by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3C, 3D). E. coli treated with FITC-labeled 4 showed intense areas of green fluorescence, indicating adsorption of conjugate to the cell wall. In contrast, a negatively charged control dendrimer FITC-G5(GA)16 lacking a targeting ligand did not show any adsorption. Treatment with 4 led to aggregates of E. coli which might be attributable to crosslinking of the multivalent dendrimers with multiple cells.4, 16

The photochemical release of ciprofloxacin from 2 ONB-Cipro was evaluated by exposing it to UVA light (365 nm; exposure time = 0–30 min) followed by reversed phase UPLC analysis of the photolysed product as a function of exposure time (Fig. 4A). After brief irradiation, a new peak appeared with a retention time of tR = 7.2 min which was identical to that of free ciprofloxacin. The peak grew as a function of exposure time with the concomitant consumption of ONB-Cipro 2 (tR = 9.5 min). Area under the curve (AUC) analysis (Fig. 4B) provided a half-life (t1/2) of 15 min for the decay of ONB-Cipro which occurred with a first-order rate constant of 8.2 × 10−4 s−1. After 30 min of irradiation, 80% release of ciprofloxacin from 2 ONB-Cipro was achieved.

Fig. 4.

Light-controlled release of ciprofloxacin from ONB-Cipro 2 (top) or from the ONB-Cipro conjugated G5 dendrimer 4 (bottom) through cleavage of the ONB cage. (A) UPLC traces for release kinetics of Cipro by UVA (365 nm) irradiation of 2 (0.13 mM in 10% aq. MeOH), and (B) a plot of Cipro release (%) against exposure time determined by AUC analysis of each UPLC trace. (C, D) UPLC and UV–vis traces (inset, top) measured for the release kinetics of 3 and 4 (31.7 µM in water) as a function of UV exposure time.

Light-controlled ciprofloxacin release was next investigated for conjugates 3 G5(ONB-Cipro)8.5 and 4 G5(PMB)1.1(ONB-Cipro)8.5 and monitored by UPLC and UV–vis spectrometry (Fig. 4C, 4D). Overlaid UPLC traces acquired for each conjugate after UV exposure showed a sharp peak for free ciprofloxacin (tR = 7.2 min) which grew within the broad dendrimer peak. Ciprofloxacin release was also evidenced by the shift in the broad dendrimer peaks to faster retention times over the course of UV exposure, reflecting their reduction to smaller NPs due to the loss of the drug payload. No significant fraction of intact 3 was observed after ≥15 min of irradiation. UV–vis spectral traces (top, inset) acquired over the irradiation time course showed a notable change in the absorbance at 280 nm which reflects photocleavage of the ONB linker (quantum efficiency Φ = 0.29)32 as observed in other drug release systems.32–34 These analyses demonstrate the effectiveness of UV in the active control of ciprofloxacin release from its ONB photocaged form on LPS-targeted dendrimers 3 and 4.

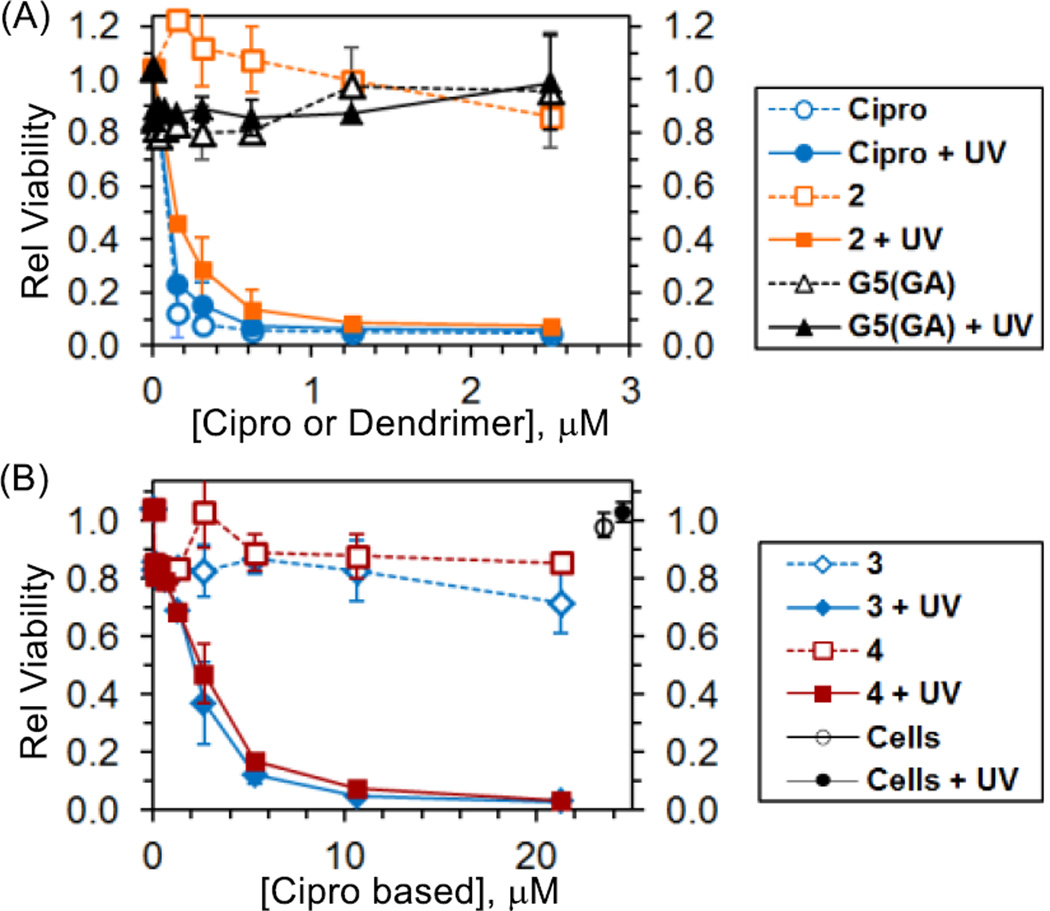

We then investigated the light-controlled bactericidal activity of conjugates 3 and 4 using a turbidity assay.16 The optical density at 650 nm (OD650) of E. coli cultures treated with the conjugates was measured over time. A drop in OD reflects a decrease in bacterial viability. Fig. 5A shows control experiments involving free ciprofloxacin, photocaged ciprofloxacin (2) and a control dendrimer. Free ciprofloxacin displayed potent antibacterial activity with an MIC50 value of 80 nM (lit. MIC50 = 94 nM39). In contrast, a glutarate-terminated control dendrimer lacking the conjugated drug G5(GA) showed no significant effect on the cell viability at concentrations of up to 2.5 µM. UVA exposure did not impact the activity of free ciprofloxacin or the dendrimer control. However 2 ONB-Cipro showed bactericidal activity as potent as free Cipro after UVA exposure, demonstrating the efficient release of drug in a functional form by long wavelength UV (365 nm). Fig. 5B summarizes the viability of E. coli treated with conjugates 3 or 4, each carrying photocaged ciprofloxacin. Unlike bactericidal UVC (200–280 nm), exposure to longer wavelength UVA (315–400 nm) alone had no effect on the viability of untreated bacterial cells (Fig. 5B).30 Likewise treatment of bacterial cells with each conjugate without UV exposure (−UV) led to minimal changes in viability. These results suggest that tight LPS binding by each conjugate is insufficient for cytotoxicity, likely due to poor penetration of the conjugate into the inner cell wall structure and/or to the lack of intracellular ciprofloxacin release if uptake occurs (Fig. 1). In contrast, treatment of bacteria with 3 and 4 with concomitant UVA irradiation for 30 min dramatically increased the antibacterial efficacy of the conjugates. This decrease occurred as a function of dose with an MIC50 value of ≈ 230 nM (2.0 µM) on a dendrimer (or Cipro) basis. Although this antibacterial activity is lower than that of free ciprofloxacin, perhaps in part due to incomplete drug release, these results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of using a photocage and light as a means to temporally modulate the activity of ciprofloxacin in bacteria-targeted delivery. Finally, 3 and 4 showed a lack of phototoxicity in human KB cells, and caused no hemolysis of red blood cells, supportive of their selectivity and potential biocompatibility (Figure S7, S8).

Fig. 5.

Light control of antibacterial activity against E. coli (XL-1) as determined by a turbidity assay. (A) Effect of UVA (365 nm) exposure on the cells treated with ciprofloxacin, 2 or control dendrimer G5(GA). (B) UVA-triggered enhancement in antibacterial activity of 3 and 4. Bacterial cells (1 × 106 CFU) were treated with each, exposed to UVA for 30 min and then incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Data are the average of replicate experiments (N = 2) with error bars representing SD.

In conclusion, the present study validated, for the first time, an actively controlled, release mechanism in bacteria for the effective delivery of ciprofloxacin using an LPS-targeted dendrimer nanoconjugate. Use of this novel approach for bacteria-targeted drug delivery provides potential benefits in enhancing the selectivity, and thus the therapeutic index of the payload drug molecule. As potent antibiotics such as Ciprofloxacin tend to exhibit unwanted side effects, greater selective targeting and control of delivery is highly desirable. We believe this light-based release mechanism has the potential to improve targeted NP delivery of antimicrobial compounds to bacterial and fungal pathogens, which unlike cancer cells resist NP penetration. Future efforts will be made to validate the applications of this temporally-controlled delivery against drug resistant pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH National Cancer Institute 1R21CA191428, and the British Council and Department for Business Innovation & Skills through the Global Innovation Initiative (GII 207).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: synthetic details and spectral copies of 2–4; photorelease studies and turbidity assay. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Bowler PG, Duerden BI, Armstrong DG. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:244–269. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.244-269.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu H, Ho PL, Tong E, Wang L, Xu B. Nano Lett. 2003;3:1261–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metallo SJ, Kane RS, Holmlin RE, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4534–4540. doi: 10.1021/ja030045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi SK, Myc A, Silpe JE, Sumit M, Wong PT, McCarthy K, Desai AM, Thomas TP, Kotlyar A, Banaszak Holl MM, Orr BG, Baker JR. ACS Nano. 2013;7:214–228. doi: 10.1021/nn3038995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kell AJ, Stewart G, Ryan S, Peytavi R, Boissinot M, Huletsky A, Bergeron MG, Simard B. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1777–1788. doi: 10.1021/nn700183g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J-J, Jeong KJ, Hashimoto M, Kwon AH, Rwei A, Shankarappa SA, Tsui JH, Kohane DS. Nano Lett. 2014;14:1–5. doi: 10.1021/nl3047305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang JH, Super M, Yung CW, Cooper RM, Domansky K, Graveline AR, Mammoto T, Berthet JB, Tobin H, Cartwright MJ, Watters AL, Rottman M, Waterhouse A, Mammoto A, Gamini N, Rodas MJ, Kole A, Jiang A, Valentin TM, Diaz A, Takahashi K, Ingber DE. Nat. Med. (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2014;20:1211–1216. doi: 10.1038/nm.3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikaido H. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:2348–2368. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:2754–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fasting C, Schalley CA, Weber M, Seitz O, Hecht S, Koksch B, Dernedde J, Graf C, Knapp E-W, Haag R. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2012;51:10472–10498. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy R. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1996;6:692–702. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu J, Shi X. Mater. Chem. B. 2013;1:4199–4211. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20724b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farokhzad OC, Langer R. ACS Nano. 2009;3:16–20. doi: 10.1021/nn900002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majoros IJ, Williams CR, Becker A, Baker JR., Jr Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1:502–510. doi: 10.1002/wnan.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong PT, Tang S, Tang K, Coulter A, Mukherjee J, Gam K, Baker JR, Choi SK. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:1149–1156. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01690d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin P-C, Yu C-C, Wu H-T, Lu Y-W, Han C-L, Su A-K, Chen Y-J, Lin C-C. Biomacromolecules. 2012;14:160–168. doi: 10.1021/bm301567w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnamurthy VM, Quinton LJ, Estroff LA, Metallo SJ, Isaacs JM, Mizgerd JP, Whitesides GM. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3663–3674. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarker P, Shepherd J, Swindells K, Douglas I, MacNeil S, Swanson L, Rimmer S. Biomacromolecules. 2010;12:1–5. doi: 10.1021/bm100922j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson GA, Muthukrishnan N, Pellois J-P. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;24:114–123. doi: 10.1021/bc3005254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson GA, Ellis EA, Kim H, Muthukrishnan N, Snavely T, Pellois J-P. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feazell RP, Nakayama-Ratchford N, Dai H, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8438–8439. doi: 10.1021/ja073231f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ojima I. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:108–119. doi: 10.1021/ar700093f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubowchik GM, Walker MA. Pharmacol. Therap. 1999;83:67–123. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong PT, Choi SK. Chem. Rev. (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2015;115:3388–3432. doi: 10.1021/cr5004634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu X, Agasti SS, Vinegoni C, Waterman P, DePinho RA, Weissleder R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;23:1945–1951. doi: 10.1021/bc300319c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sortino S. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:301–318. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong R, Kohane DS. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2012;4:638–662. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamblin MR, Hasan T. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004;3:436–450. doi: 10.1039/b311900a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta A, Avci P, Dai T, Huang Y-Y, Hamblin MR. Advances in Wound Care. 2013;2:422–437. doi: 10.1089/wound.2012.0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomalia DA, Naylor AM, William I, Goddard A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1990;29:138–175. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi SK, Thomas T, Li M, Kotlyar A, Desai A, Baker JR., Jr Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2010;46:2632–2634. doi: 10.1039/b927215c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi SK, Thomas TP, Li M-H, Desai A, Kotlyar A, Baker JR. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012;11:653–660. doi: 10.1039/c2pp05355a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi SK, Verma M, Silpe J, Moody RE, Tang K, Hanson JJ, Baker JR., Jr Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:1281–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong PT, Chen D, Tang S, Yanik S, Payne M, Mukherjee J, Coulter A, Tang K, Tao K, Sun K, Baker JR, Jr, Choi SK. Small. 2015;11:6078–6090. doi: 10.1002/smll.201501575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi SK, Leroueil P, Li M-H, Desai A, Zong H, Van Der Spek AFL, Baker JR., Jr Macromolecules. 2011;44:4026–4029. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mullen DG, Fang M, Desai A, Baker JR, Jr, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. ACS Nano. 2010;4:657–670. doi: 10.1021/nn900999c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Mol NJ, Fischer MJE. Handbook of Surface Plasmon Resonance. Vol. 5. Cambridge, UK: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2008. pp. 123–172. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roychoudhury S, Twinem TL, Makin KM, McIntosh EJ, Ledoussal B, Catrenich CE. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;48:29–36. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.