Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection causes induction of several tumor/cancer stem cell (CSC) markers and is known to be a major risk factor for development of HCC. Therefore, drugs that simultaneously target viral replication and CSC properties are needed for a risk-free treatment of advanced stage liver diseases including HCC. Here, we demonstrated that (Z)-3,5,4’-trimethoxystilbene (Z-TMS) exhibits potent anti-tumor and anti-HCV activities without exhibiting cytotoxicity to human hepatocytes in vitro or in mice livers. Diethylnitrosamine (DEN)/carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) extensively induced expression of DCLK1 (a CSC marker) in the livers of C57BL/6 mice following hepatic injury. Z-TMS exhibited hepatoprotective effects against DEN/CCl4-induced injury by reducing DCLK1 expression and improving histological outcomes. The drug caused bundling of DCLK1 with microtubules and blocked cell cycle progression at G2/M phase in hepatoma cells via downregulation of CDK1, induction of p21cip1/waf1 expression, and inhibition of Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation. Z-TMS also inhibited proliferation of erlotinib-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cells (H1975) bearing the T790M EGFR mutation most likely by promoting autophagy and nuclear fragmentation. In conclusion, Z-TMS appears to be a unique therapeutic agent targeting HCV and concurrently eliminating cells with neoplastic potential during chronic liver diseases including HCC. It may also be a valuable drug for targeting drug-resistant carcinomas and cancers of the lungs, pancreas, colon, and intestine in which DCLK1 is involved in tumorigenesis.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide with a dismal 5-year survival rate of 11% (1, 2). Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major risk factor for the development of HCC (1, 3). HCV patients coinfected with other viruses or with metabolic comorbidity (obesity and diabetes) exhibit faster progression of liver disease and are difficult to treat with standard interferon based treatment regimens (3). The combinations of direct-acting anti-viral (DAA) drugs against three key HCV nonstructural proteins (NS3, NS5A, and NS5B) have shown remarkable efficacy (>90%) for curing the infection (4, 5). However, these drugs are inaccessible to millions of patients and a complete recovery of damaged liver by the HCV treatments alone has not been proven.

The majority of HCC cases are normally diagnosed at late stages, and the use of curative surgery or other treatments are less successful (6, 7). Kinase inhibitors have been shown to increase survival only by a few months or are ineffectual in advanced HCC patients (8). The activation of multiple signaling pathways and enrichment of tumor/cancer stem cells (CSCs) within the tumor appear to mediate HCC multi-drug resistance (9-11). CSCs represent small subpopulations within a tumor that possess self-renewing capabilities and the ability to differentiate into a heterogeneous lineage within the tumor mass (12-14).

We previously demonstrated a positive correlation between the levels of HCV replication and expression of an array of CSC-associated markers including doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1) (15, 16). These changes appear to promote cellular dedifferentiation and the gain of CSC properties in HCV-positive cells. We have further demonstrated that knockdown of DCLK1 results in downregulation of HCV replication, cell migration, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in multiple cancer cell lines and in mouse models (15, 17). There is currently no clear choice for targeting CSCs efficiently (18, 19). DCLK1 is considered to be an important target for the treatment of tumors of the liver, pancreas and colon. HCV also induces epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) that facilitates HCV entry into the cells and promotes progression of liver diseases (20, 21). The EGFR inhibitor, erlotinib has been shown to downregulate HCV RNA levels in a mouse model (20). These observations clearly suggest that cellular kinases (DCLK1 and EGFR) are critical components of HCV-induced chronic liver diseases.

The naturally occurring antioxidant, resveratrol (RVT) has been extensively studied for possible health benefits (22, 23) including anti-cancer effects (24-26). However, its potential benefits could not be demonstrated in patients with malignancy due to poor absorption and extremely low bioavailability (23, 27). The structurally related analog (Z)-3,5,4’-trimethoxystilbene (Z-TMS), originally isolated from the bark of Virola elongate, has been shown to inhibit microtubule polymerization, induce G2/M arrest, and inhibit ornithine decarboxylase activity (28, 29). Z-TMS also has long half-life and limited drug clearance when administered intravenously (30, 31). Here, we report mechanism(s) of Z-TMS's antiviral and antitumor activities in several in vitro models and in DEN/CCL4-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 mouse model. Z-TMS exerts its inhibitory effects on tumors by diminishing DCLK1+ cell population, interference with DCLK1-microtubule dynamics, cell-cycle arrest at G2/M phase, promotion of autophagy, and causing nuclear fragmentation. It is considerably effective against erlotinib-resistant T790M mutant lung carcinoma cells and may evolve as a potential candidate for the treatment of HCV-induced advanced liver diseases including HCC.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, antibodies, cells, and cell culture

The non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma cells (NSCLCs, H1975) and primary human hepatocytes were purchased from ATCC and BD Biosciences respectively. All other cells (endogenous) were tested before start of the studies using MycoAlert™ Kit (Lonza) and were found negative for Mycoplasma. The parent cell line Huh7 and human hepatocytes were recently evaluated (January 14, 2016) for Hantaan virus, LCMV, and Mycoplasma using PCR by IDEXX Bioresearch and were negative for these agents. The characteristics of hepatoma Huh7-derived cell lines (Huh7.5, GS5 and FCA4) have been described previously (15, 16, 32, 33). HCV+DCLK1+ hepatoma cells were generated by transducing G418-resistant FCA4 cells with lentivirus expressing DCLK1 (isoform 1) tagged with RFP at the N-terminus. The cells were cultured as described previously (34). Resveratrol (Sigma) and (Z)-3,5,4’-trimethoxystilbene (Z-TMS, Cayman) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20 °C. EGFR (aa 695-1210) and luciferase assay kit were purchased from Promega. The antibodies were purchased from the following sources: DCLK1 (ab31704), NS5B (35586), actin (ab1801), from Abcam; LC3B (2775), cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175) (9664), p-Akt (4069), from Cell Signaling; anti-NS3 antibody (217-A) from Virogen.

Z-TMS treatment of hepatoma cells infected with HCV

The cell culture generated JFH1 HCV-2a infectious particles (HCVcc) were produced as described previously (35). In brief, JFH1 RNAs were electroporated into Huh7.5 cells and HCVcc particles were determined in cell culture supernatant. Huh7.5 cells were infected with HCVcc at m.o.i of 1 for 48 hours. Subsequently, the HCVcc-infected cells were treated with Z-TMS (1 μM) or equivalent amounts of DMSO in triplicates for 48 hours. The untreated infected cells were considered as positive control whereas uninfected Huh7.5 cells served as negative control for detection of the HCV RNA by qRT-PCR. The HCV RNA copy numbers per microgram of total RNAs in Z-TMS were calculated and compared with vehicle treated and untreated samples. JFH-1/GND RNAs (replication defective JFH1 mutant) were used as negative control. In most of the experiments, HCV-infected cells were serum starved for 4 hours before harvesting. Total RNAs from the HCV replicon expressing cells were isolated and subjected to RT-PCR as described previously (15).

Western blot, cell survival, and cell proliferation

Cells treated with resveratrol, Z-TMS or DMSO were washed with PBS, collected, and lysed with mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER) (Thermo Scientific). Western blots were performed using 30-40 μg of cell lysates (15, 34) and antibodies were diluted as recommended by the suppliers. Each Western blot was repeated three times. To evaluate target protein to actin ratio, band intensities were calculated using GelQuant software and mean ratios were presented. Cell viability was determined using CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution (Promega) as recommended by the supplier.

H1975 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Z-TMS treated and untreated H1975 cells in a 96-well culture plate were stained with DRAQ5 and scanned with Operetta (Perkin-Elmer). Each treatment was done in quadruplets and each well was analyzed for 5 different fields for the analysis of nuclear fragmentation. The images (average of 5 fields for each well) were analyzed by Columbus software. Wound healing assay for cell migration was carried out as described previously (34).

Cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry

Cells treated were with Z-TMS (1μM) or DMSO for 48 hours, harvested, and washed with PBS. The pelleted cells were resuspended in PBS containing paraformaldehyde (2%) for 1 hour at 4°C, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, resuspended and fixed in 70% ethanol, and incubated overnight at 4°C. The cells were treated with RNase A (200 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (PI, 50 μg/ml) (Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark and stored at 4°C until acquisition of the flow cytometer data. The instrument was calibrated with unstained cells and sorted for PI intensity. A total of 10,000 cell events were collected. Flow cytometric data were collected and analyzed using the CELLQuest program (Becton Dickinson).

Kinase activities

EGFR kinase assay was performed using the ADP-Glo kinase assay and recombinant EGFR representing amino acids 695-1210 of the wild type using Promega's protocol. The kinase was treated with 1 μM of Z-TMS or erlotinib in triplicates, and luciferase read-out for the EGFR kinase activities were compared with the untreated control. The experiment was repeated twice.

HCC survival data and immunohistochemistry of human liver tissues

To evaluate the relationship between DCLK1 expression levels and survival of HCC patients, a Kaplan-Meier plot was generated using the liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC, total 369 cases) data provided by the TCGA Research Network (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) using the UCSC Genome Browser. Immunohistochemical staining of liver tissues from patients with HCV and HCC were obtained from the LTCDS (Minneapolis) (15, 34).

Hepatoma xenografts and treatment of C57BL/6 mice with Z-TMS

All mice studies reported here were pre-approved (protocols # 12-041 and 15-083) and supervised by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which adheres to the PHS Policy IV.B.3. Athymic nude Balb/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed in pathogen-free conditions. One million Huh7 cells were washed with PBS three times, resuspended in the same buffer, and injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of 4–6 week old mice as reported previously (34). Tumors were measured with calipers and the volumes were calculated using formula: 0.5 × (length × width2).

Adult immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice (n=30, 8 weeks old, generated by in-house breeding at OUHSC Rodent Barrier Facility) were randomized into six groups (5 mice/group). Groups 1 through 3 received two intraperitoneal injections of diethylnitrosamine [DEN, 25 mg/kg body weight (BW), one injection per week] followed by twice-weekly injections of CCl4 (1 ml/kg BW) for the next 7 weeks. Except group 1, groups 2 and 3 were also treated with 20 and 40 mg/kg BW of Z-TMS dissolved in DMSO respectively. Group 4 received only Z-TMS (40 mg/kg BW) to determine its possible toxicity. Groups 5 and 6 served as DMSO and untreated controls respectively during the same period. At the termination of the experiments, all the animals were euthanized and subjected to necropsy for collection and analysis of blood or tissues of different organs.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in biological replicates of at least three and repeated to confirm the results. The graphs were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The p-values were calculated using Student's t-Test. Results with p≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

(Z)-3,5,4’-trimethoxystilbene (Z-TMS) is a potent HCV inhibitor

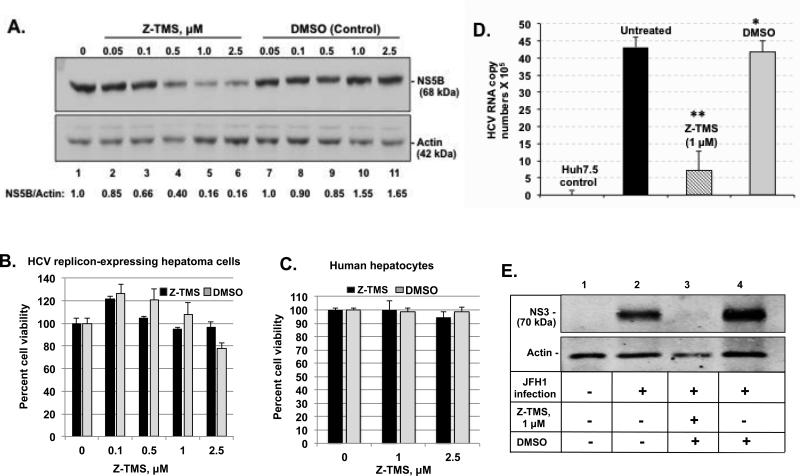

Published reports suggest potential benefits of resveratrol (3,5,4'-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene, RVT) and its analogues on human health [reviewed in (36), (37)]. We initially tested the anti-HCV activities of RVT and its natural analogue, (Z)-3,5,4’-trimethoxystilbene (Z-TMS) in hepatoma cell lines (GS5 and FCA4) expressing HCV-1b subgenomic replicons (16, 34). The results suggested that Z-TMS is nearly 100 times more potent in downregulating the levels of HCV NS5B polymerase, which is now considered a core target of direct-antiviral therapy (results not shown). Next, FCA4 cells were treated with varying amounts (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.5 μM) of Z-TMS or equivalent amounts of DMSO for 48 hours. The total lysates prepared from drug-treated and untreated cells were analyzed for NS5B and actin (loading control) levels. The data suggest that Z-TMS inhibits NS5B expression in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1A, lanes 2-6). Similar results were obtained with GS5 cells (not shown). The DMSO solvent control had no inhibitory effect on the NS5B levels (lanes 7-11) as compared to the untreated control (lane 1). Under these conditions (0.1 μM to 1.0 μM Z-TMS for 48 hours treatment), FCA4 cells as well as normal human hepatocytes remained fully viable (Figs. 1B and 1C).

Figure 1.

Determination of dose-response of Z-TMS for the inhibition of HCV replication and evaluation of cytotoxicity. (A) Huh7 hepatoma cells expressing HCV-1b replicon (FCA4) were treated for 48 hours with varying amounts of Z-TMS (lanes 2-6) or DMSO (lanes 7-11). The total lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis for NS5B. Lane 1, untreated control. The NS5B band intensities in each lane were quantitated using GelQuant and NS5B to actin ratios were calculated. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (B-C) Determination of cytotoxicity of Z-TMS (at 0.1 to 2.5 μM) or corresponding DMSO using cell viability assay for FCA4 cells or human hepatocytes cultured on collagen 1-coated plates (p<0.02). Each treatment was carried out in triplicates, and data are presented as mean±SD. (D) Z-TMS inhibits replication of HCV-2a (JFH1). Huh7.5 cells in 12-well culture plates were infected with JFH1 virus (HCVcc) for 48 hours. Subsequently, the cells were treated with Z-TMS (1 uM) or vehicle in triplicates for the next 48 hours. The HCVcc-infected cells (untreated, solid black bar) were considered as positive control, whereas untreated parent Huh7.5 cells (Huh7.5 control) served as negative control for detection of HCV RNA by qRT-PCR. The HCV RNA copy numbers per microgram of total RNAs in Z-TMS treated cells (hatched bar) were compared with DMSO treated (gray bar) and untreated (black bar) samples. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. * and ** indicate p values <0.05 and <0.0001 respectively. (E) Western blot analysis for detection of NS3 in total lysates of the Z-TMS-treated and untreated HCVcc-infected cells using well-characterized monoclonal anti-NS3 antibody.

To examine whether Z-TMS inhibits HCV replication in an HCV infection model, Huh7.5 cells were infected with tissue culture generated JFH1 viruses (HCVcc) for 48 hours to allow replication of the viral RNA. The infected cells were then treated with 1 μM of Z-TMS or vehicle for 48 hours. Total RNAs isolated from these cells were subjected to qRT-PCR to determine levels of HCV replication. As expected, the JFH1 RNA copy number was drastically reduced (~10 times) by Z-TMS treatment as compared to the DMSO-treated or untreated cells (Fig. 1D). The results were fully corroborated by the dramatic reduction in NS3 level (Fig. 1E, lane 3) as compared to the controls (lanes 2, 4).

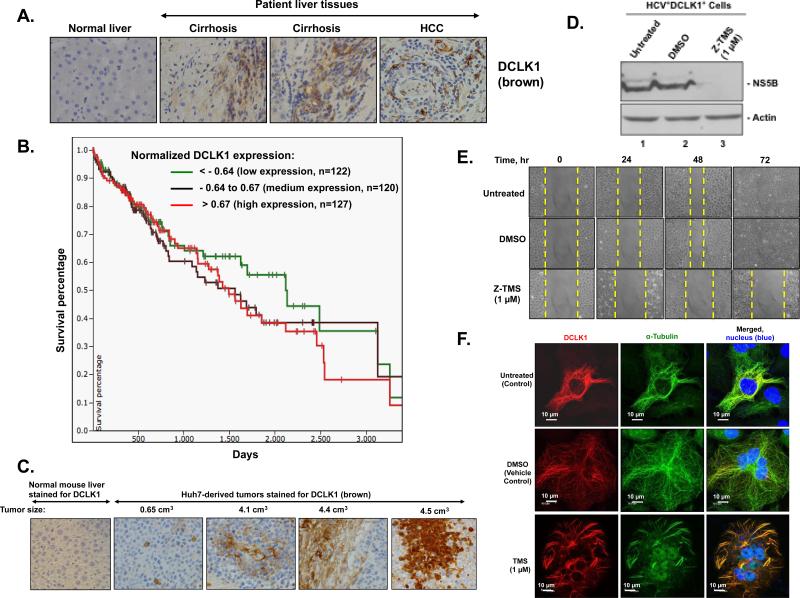

Z-TMS disrupts DCLK1-microtubule dynamics

Microtubules are highly dynamic structures whose regulations are critical for HCV replication, cell division, cell migration and cell polarity. The CSC marker DCLK1 associates with microtubules and stimulates polymerization of tubulins. We have previously shown that DCLK1 is overexpressed in liver tissues derived from patients with cirrhosis and HCC. Its expression is also correlated with activation of inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic signals as well as hepatoma cell migration (34). These observations led us to investigate the significance of DCLK1 overexpression in patient survival and effects of Z-TMS on DCLK1 interaction with microtubules or microtubule dynamic instability. As shown in Fig 2A, DCLK1 is overexpressed in liver tissues of HCV-positive patients with cirrhosis and HCC but not in normal liver. The Kaplan-Meier plot suggests that the 5-year survival rate is approximately reduced by three times in HCC patients (n= 369) with hepatic DCLK1 overexpression (Fig. 2B, red and black lines) as compared to the patients with low DCLK1 levels (green line). In a mouse tumor xenograft model described previously (34), large tumors (average size of 4-4.5 cm3) derived from Huh7 cells exhibited extensive staining for human DCLK1 except the one that was smaller in size (0.65 cm3) (Fig. 2C). Because of DCLK1's important roles in microtubule dynamics, HCV replication and tumor growth in addition to the ability of HCV+DCLK1+ hepatoma cells to form spheroids (15, 16), we examined the effects of Z-TMS on HCV+DCLK1+ cells. These cells were isolated from FCA4 cells co-expressing recombinant RFP-DCLK1 and HCV subgenomic replicon by FACS method. As shown in Fig. 2D, expression of HCV NS5B polymerase in HCV+DCLK1+ hepatoma cells was significantly reduced by 1 μM of Z-TMS treatment (lane 3) as compared to controls (lanes 1 and 2). Z-TMS treatment also caused significant inhibition in the proliferative potential of these cells (Fig. 2E). We carried out confocal immunofluorescence microscopy to determine localization of DCLK1 with microtubule in these cells following Z-TMS treatment. The results revealed that Z-TMS induces bundling of microtubules and speckle-like structures of DCLK1-microtubule complexes (Fig. 2F, lower panel). However, the untreated and DMSO-treated cells exhibit normal distribution of DCLK1 (red) and tubulin (green) or their complexes (yellow). Collectively, these results indicate a direct relationship of DCLK1 with the survival of HCC patients and possibility of targeting HCV-positive DCLK1-overexpressing hepatoma cells by Z-TMS.

Figure 2.

Z-TMS exhibits anti-HCV and anti-tumor activities by interfering with DCLK1-microtubules dynamics. (A) Immunohistochemical staining showing DCLK1's extensive expression (brown staining) in the livers of HCV-positive patients with cirrhosis and HCC (20 cases studied). Blue, nucleus. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot showing progressive decrease in survival rates of HCC patients at low (green line), medium (black line) and high (red line) DCLK1 expression levels. The DCLK1 expression data were normalized by subtracting mean expression from individual values. (C) Immunohistochemical staining of Huh7 cells-derived tumors for DCLK1 expression. For tumor xenografts, each nude mouse received one million cultured Huh7 cells per injection on the flanks as reported previously (34). (D) Z-TMS inhibits FCA4-derived HCV+DCLK1+ cells. These cells represent HCV subgenomic replicon-expressing FCA4 cells that overexpress human DCLK1 tagged with RFP at N-terminus (DCLK1-RFP) and treated with Z-TMS (1 μM, lane 3) or DMSO (lane 2) for 48 hours. NS5B levels were analyzed by Western blot in the total cell lysates. Lane 1, untreated control. (E) Z-TMS inhibits HCV+DCLK1+ cell migration. The cells were treated with Z-TMS or DMSO as indicated in wound-healing assay. The space between two broken yellow lines in each sample image indicates the extent of gap/wound. (F) Confocal microscopy of HCV+DCLK1+ cells (upper panel) after staining for α-tubulin (green) and nucleus (blue). Yellow, colocalization of RFP-DCLK1 (red) with microtubules (green). Unlike controls (upper and middle panels), bundling of microtubules and sequestration of DCLK1 in the microtubule bundles (yellow, extreme right, lowest panel) are evident in Z-TMS treated cells.

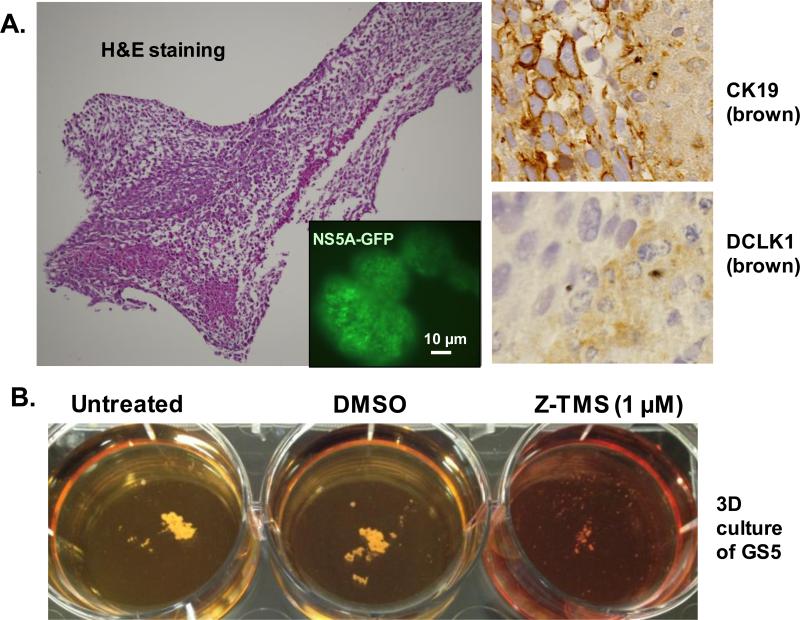

We used a 3D magnetic levitation method (38) to culture GS5 cells as visible cell spheroids/aggregates (Fig. 3A). The levels of NS5A-GFP green florescence indicated continued HCV replication in the spheroid-like cultures (Fig. 3A inset). Immunohistochemical staining of these aggregates revealed different cell phenotypes. While large cells displayed extensive CK19 expression (circulating tumor cell marker) and cell-to-cell contacts, a low number of unique small cells were DCLK1-positive. This observation clearly suggests heterogeneous cell phenotypes in the spheroids. Z-TMS successfully inhibited growth of this cellular mass (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Z-TMS inhibits hepatoma cell growth in 3D cell culture model. (A) Characterization of spheroids/aggregates derived from GS5 cells (1 million) that were developed in three weeks by magnetic levitation method. Immunohistochemical staining (H&E and CK19) of the aggregates shows cell-to-cell-contacts. Both DCLK1+ and DCLK1− staining was observed indicating heterogeneity of cells in the aggregates. Blue, nuclear staining. Inset, live image of the same spheroid/aggregates shows expression of HCV NS5A-GFP (green). (B) Effects of Z-TMS on spheroid growth in 3D culture model. GS5 spheroids/aggregates were grown as described above for 2 weeks and treated with DMSO or Z-TMS (1 μM) or untreated. The visible cell masses were photographed four weeks post-treatment. This experiment was repeated once and a representative photograph is shown.

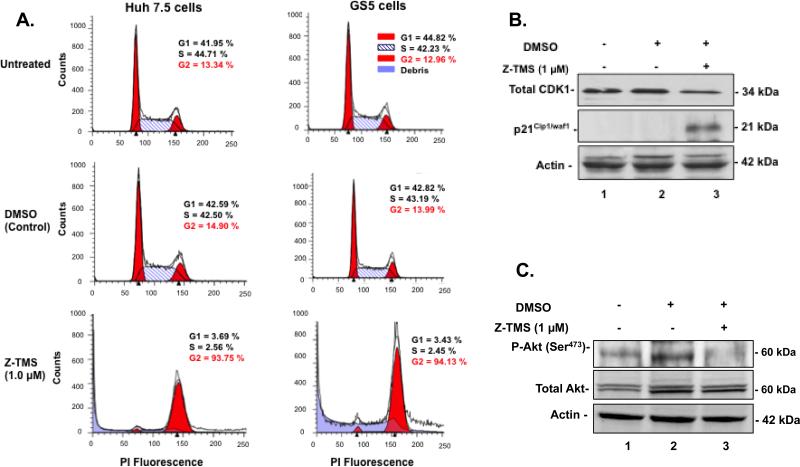

Z-TMS causes G2/M cell cycle arrest, inhibition of Akt phosphorylation and upregulation of p21Cip1/Waf1 in hepatoma cells

GS5 cells, which express a NS5A-GFP chimeric protein encoded by HCV-1b subgenomic RNAs, and Huh 7.5 cells were treated with 1 μM of Z-TMS for 48 hours and stained with propidium iodide for cell cycle analysis. The results clearly suggest that most GS5 cells and Huh7.5 parent cells were stalled in the G2/M phase (>90%) with a concomitant reduction in the G1 and S-phases (Fig. 4A). However, DMSO-treated and untreated cells showed similar cell cycle distribution. The result shows that the observed change in cell cycle was induced by Z-TMS and not by the DMSO (solvent). Similar Z-TMS effects were observed for other hepatoma cell lines (Huh7 and FCA4, not shown). Next, total lysates of the drug treated and untreated cells were subjected to Western blot analysis for detection of proteins involved in cell cycle checkpoints. Z-TMS treatment caused downregulation of total cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) with a concomitant induction of p21Cip1/Waf1 expression (Fig. 4B, lane 3), which is a potent inhibitor of CDK1 and CDK2. Also, p21Cip1/Waf1 mediates growth arrest and cellular senescence. Activation of Akt overcomes a G2/M cell cycle checkpoint induced by DNA damage (39). Therefore, successful blockage of cancer cells at G2/M phase should also be accompanied by the downregulation of Akt. Treatment of GS5 cells with Z-TMS (1 μM) resulted in significant downregulation of Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation without affecting total Akt level (Fig. 4C, lane 3). Taken together, Z-TMS appears to induce G2/M cell cycle arrest by induction of p21Cip1/Waf1 and downregulation of Akt signaling.

Figure 4.

Z-TMS induces cell-cycle arrest at G2/M phase that is accompanied by the activation of p21Cip1/waf1, downregulation of CDK1, and dephosphorylation of Akt. (A) The GS5 cultured cells well treated with 1 μM of Z-TMS or DMSO (control, vehicle) for 48 hour and subjected to cell cycle analysis following treatment with propidium iodide. (B, C) Western blot analysis for Z-TMS-led inhibition of signals that promote cell cycle progression and cell survival in GS5 cells treated with Z-TMS (lane 3) or vehicle (lane 2). Detection of p21Cip1/waf1 and total CDK1 (B) or activated Akt (determined by P-Akt (Ser473) and total Akt (C). In each case, untreated cells were considered as regular (uninhibited) control. Actin band in each lane was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and representative data are shown.

Broad-spectrum antitumor activities of Z-TMS

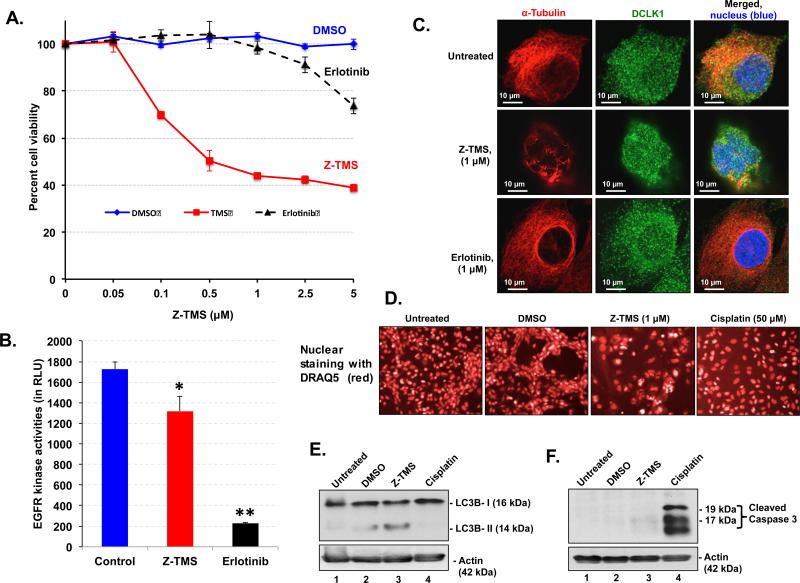

Since Z-TMS inhibits Akt activation, the status and function of its upstream regulator epidermal growth factor (EGFR) was examined. Our interest in EGFR investigation stems in part from the observation that erlotinib, an EGFR inhibitor, diminishes HCV entry into cells and reduces HCV replication in a mouse model (20). Because of the lack of an EGFR mutant hepatoma model, we used a well-characterized erlotinib-resistant lung adenocarcinoma (NSCLC) H1975 cells that contains the T790M gatekeeper mutation in EGFR to determine the effect of Z-TMS on these cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, Z-TMS significantly reduced survival of H1975 cells in the 0.1 μM to 1.0 μM range within 48 hour, whereas erlotinib failed to reduce cell survival even though it was fully active against the wild-type EGFR kinase domain (aa 695-1210) (Figs. 5A and 5B). The luciferase-based EGFR activity assay suggests that erlotinib efficiently inhibited (90%) the kinase activities, whereas Z-TMS failed to exhibit strong inhibition in spite of reducing H1975 survival. Confocal immunostaining clearly revealed that only Z-TMS but not erlotinib induced microtubule bundling (Fig. 5C, middle panel). Unlike the intense co-localization of DCLK1 with microtubules in DCLK1-overexpressing hepatoma cells (Fig. 2F), we observed mostly punctate staining of DCLK1 in H1975 probably due to alternatively spliced or post-translationally modified forms that do not preferentially bind microtubules (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Z-TMS inhibits viability of erlotinib-resistant non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma cells (NSCLC, H1975) bearing the T790M mutation via autophagy and nuclear fragmentation. (A) The cells were treated with varying amounts of Z-TMS, erlotinib or DMSO for 48 hours and subjected to MTS cell viability assay. The experiment was repeated three times and average ± standard deviation was plotted (p<0.002). (B) The kinase activity was measured using ADP-Glow kinase assay for human EGFR (aa 695-1210) and expressed as relative luciferase unit (RLU). The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. * and ** indicate p values <0.05 and <0.01 respectively (C) Confocal microscopy of H1975 cells treated with 1 μM of Z-TMS or erlotinib (middle and lower panel respectively) for 48 hours and stained by immunofluorescence staining protocol for α-tubulin (red) and DCLK1 (green). Blue, nucleus. The untreated cells were used as a control (upper panel). A representative staining pattern for the localization of DCLK1 and microtubules is shown here. (D) A representative scanned field image of Z-TMS treated and untreated H1975 cells following staining with DRAQ5 (red, nucleus). Each treatment was done in quadruplets and each well was analyzed for 5 different fields. (E, F) Western blot for Z-TMS-treated (lane 3) and control (lanes 2, 3) H1975 cell lysates probed for LC3B or cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175). Presence of LC3B-II indicates autophagy (E, lane 3). Cisplatin treated cells were used as a positive control for the apoptosis marked by cleaved caspase 3 (F, lane 4).

To understand the mechanism of Z-TMS-induced cell death, H1975 cells were cultured in a 96-well plate and treated with Z-TMS (1 μM) in quadruplets. After fixing the cells, nuclei were stained and the extent of nuclear fragmentation was assessed. The data suggest that Z-TMS induces nuclear fragmentation in nearly 70%-80% cells as compare to the untreated or DMSO or cisplatin (50 μM)-treated controls (Fig. 5D). Total lysates of H1975 cells treated with the drugs as described above showed activation of autophagy markers, LC3B-I and LC3B-II proteins in Z-TMS-treated cell lysate (Fig. 5E, lane 3), which were much higher than the corresponding controls (lanes 1, 2 and 4). Similar Western blot analysis suggested that only cisplatin, but not Z-TMS, induces cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175), which marks cell-death by apoptosis (Fig. 5F). Thus, Z-TMS appears to induce H1975 cell death by autophagy and nuclear fragmentation.

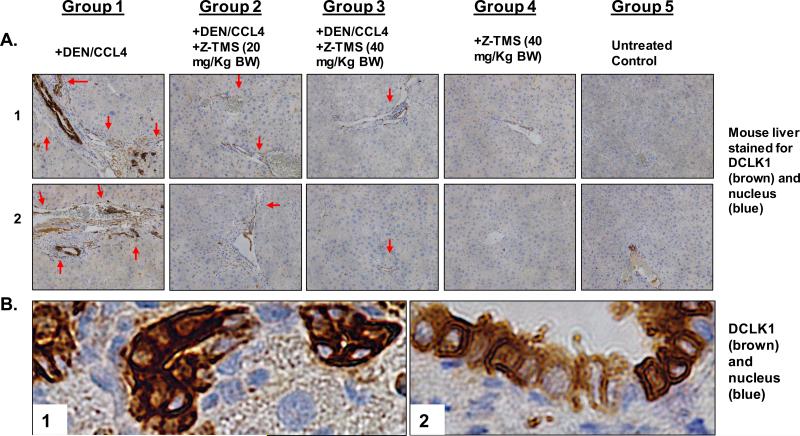

Z-TMS protects liver from DEN/CCl4 induced injury, reduces DCLK1+ cell number at injury sites and promotes hepatic recovery

The scheduled administration of diethylnitrosamine (DEN) (one injection) followed by weekly twice injections of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) induces liver injury that further progresses to fibrosis and HCC within 8-10 months (40-42). We treated immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice with two DEN [25 mg/kg body weight (BW)] injections once a week followed by administration of CCl4 (1 ml/kg BW) alone or with Z-TMS (20 or 40 mg/kg BW) twice per week for 7 weeks (groups 1 through 3 in Table 1, Fig. 6A). As expected, the DEN/CCl4 treated mice developed liver injury characterized by histologic perturbations and appearance of non-epithelial cells in the parenchyma (Fig. 6A, extreme left panels). These regions also exhibited unusually high numbers of DCLK1+ cells with intense staining in epithelial and non-epithelial compartments at the injury sites (only two liver sections from different mice of the same group are shown in upper and lower panels). This observation suggests that DEN/CCl4-led injury significantly induces DCLK1 expression in liver (highlighted in Fig. 6B). The untreated control (normal) mice livers were largely negative for DCLK1 stain or occasionally revealed a fewer DCLK1+ cells within portal triads (extreme right panel). The mice treated with Z-TMS (groups 2 and 3), which were simultaneously receiving DEN/CCL4 doses, exhibited improved histologic appearance with significantly reduced number of DCLK1+ cells as compared to group 1 (DEN/CCl4 treated, Fig. 6A). Both histologic and liver function panel (ALB, ALT, AST, ALKP and TBIL in Table 1) data clearly suggests that Z-TMS alone (group 4) does not exhibit hepatotoxicity under these treatment conditions. Instead, Z-TMS successfully protected the liver from toxic agents and improved injury most likely by eliminating or suppressing DCLK1+ cells. Mice in any group did not loose their body weight.

Table 1.

Determination of hepatotoxicity in Z-TMS treated and untreated C57BL mice by measuring serum markers after euthanizing the animals.

| ALB | ALT | AST | ALKP | TBIL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Range | 2.5-4.8 | 28-132 | 59-247 | 62-209 | 0.1-0.9 | |

| Group 1 | DEN + CCl4 | 2.6±0.1 | 78.6±15.8 | 132.2±24.6 | 90.6±15.1 | 0.9±0.2 |

| Group 2 | DEN + CCl4 + Z-TMS (20mg/Kg BW) | 2.5±0.1 | 60.0±12.0 | 164.3±85.1 | 108.3±10.1 | 0.6±0.05 |

| Group 3 | DEN + CCl4 + Z-TMS (40mg/Kg BW) | 2.4±0.3 | 109.0±17.0 | 213.5±84.5 | 144.5±25.5 | 0.7±0.1 |

| Group 4 | Z-TMS (40mg/Kg BW) | 2.6±0.3 | 50.7±6.1 | 128.7±15.4 | 52.3±16.2 | 0.9±0.6 |

| Group 5 | DMSO (40mg/Kg BW) | 2.7±0.1 | 50.5±5.3 | 234.0±42.6 | 119.0±11.9 | 0.6±0.1 |

| Group 6 | Untreated Control | 2.8±0.1 | 49.0±3.4 | 232.0±66.9 | 135.7±5.8 | 0.5±0.1 |

ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALKP, alkaline phosphatase; TBIL, total bilirubin.

Figure 6.

Z-TMS protects liver from DEN/CCl4-induced injury by downregulating DCLK1 expression and promoting normal healing in C57BL mice. (A) Immunohistochemical staining for DCLK1 (brown) in the liver of mice receiving DEN/CCl4 alone (Group 1) or with Z-TMS (Group 2, 3). Group 4 received only Z-TMS whereas Group 5 received no treatment (naïve control). Each group had 5 mice kept under similar conditions. Blue, nucleus. The representative staining results for two different mice (1 and 2) within each group are shown. DEN/CCl4 induced liver injury sites (red arrows) were highly enriched in DCLK1+ cells. However, similar areas had fewer or no DCLK1+ cells following treatment with Z-TMS (Groups 2 and 3). (B) 60x images of the representative mice 1 and 2 [+DEN/CCl4 panel, group 1] showing DCLK1+ cells with intense staining.

Discussion

Viral hepatitis, steatohepatitis and metabolic disorders substantially contribute to the development of cirrhosis and primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). End-stage liver disease due to chronic HCV infection is expected to remain a major health care issue in most countries partly due to lack of effective treatment options or inaccessibility to newly discovered drugs. Current HCC anti-neoplastic drugs, sorafenib alone or in combination with other drugs, cause considerable toxicity and only improve median overall survival by three months. Here, we have reported novel properties of Z-TMS that exerts its anti-viral and anti-tumor activities by interference with the CSC marker DCLK1, microtubule dynamics, induction of autophagy, G2/M arrest and nuclear fragmentation. The combined effects reflect in vitro efficacy of Z-TMS against the drug-resistant tumor cells such as NSCLC. Z-TMS also promotes hepatic recovery from extensive DEN (genotoxic)/CCl4 (hepatotoxic)-induced liver injury in immunocompetent C57BL mice. Thus, Z-TMS may potentially block initiation and progression of HCC by targeting DCLK1. This notion is also supported by our observation that DCLK1 downregulation results in reduction of hepatoma-like tumor growth (43). Although Z-TMS at doses 20 and 40 mg/Kg body weight did not exhibit hepatic toxicity, 20% mice showed complications in gastro-intestinal emptying. These observations warrant us for optimizing drug dosages and duration of treatment to gain its maximum health benefits.

Using subgenomic replicons and full-length JFH1 infection models of HCV, we have demonstrated the efficacy of Z-TMS against widely prevalent HCV genotypes 1 and 2. The magnetic levitation experiments revealed that growth of HCV-expressing spheroids/aggregates could also be effectively targeted by Z-TMS. The heterogeneity of this cellular mass and cell-to-cell contacts in the spheroids were revealed by immunohistochemical staining showing membranous CK19. It further showed expected DCLK1+ subpopulations (usually 1-2% of total GS5 cells) (15). Our in vivo experiments suggest that Z-TMS can diminish the DCLK1+ population in injured livers. Since DCLK1 appears to be involved in HCV replication and hepatic malignancy (15, 16, 43), it is likely that Z-TMS will be able to eliminate HCV expressing cancer stem-like cells in order to prevent progression of liver diseases.

Although normal liver parenchyma lacks detectable DCLK1 expression, DCLK1 expression and number of DCLK1+ cells are increased significantly in the stroma, regenerative cirrhotic nodules and HCC. Z-TMS clearly targeted DCLK1-microtubule dynamics that promotes HCV replication, cell migration and cell cycle progression. Microtubule stabilizing drugs (paclitaxel, docetaxel) and destabilizing drugs (vinblastine, nocodazole) have been extensively used for the treatment of cancer (44, 45). A few of these drugs have also been shown to hamper movement of the HCV replication complexes required for viral replication (46). By sequestering DCLK1 with bundled microtubules, Z-TMS will block survival, proliferation and division of DCLK1+ CSC cells.

Cancer/tumor stem cells (CSCs) are key contributors of drug-resistance, metastasis, and recurrence of tumors. At present, effectively targeting CSCs for treatment is challenging (18, 19). We previously demonstrated that HCV induces several CSC markers (CD133, Lgr5, c-Myc) including DCLK1 (47, 48). Our current data revealed that DCLK1 overexpression in HCC positive patients considerably reduces survival rate. Z-TMS causes sequestration of DCLK1 with microtubule bundles accompanied by a dramatic decrease in the NS5B polymerase level in HCV+DCLK1+ hepatoma cells. Z-TMS appears to be effective against DCLK1-positive CSCs. DCLK1 has been shown to play important roles in the development of intestinal polyps, intestinal response to radiation injury, cell survival and control of metastasis. In addition, we have shown that DCLK1 positively regulates HCV replication in knockdown and overexpression systems. Thus, Z-TMS targeted elimination of HCV-positive cells bearing CSCs footprints is likely to benefit patients with advanced liver diseases including HCC.

The molecular mechanisms of Z-TMS's anti-proliferative effects were also studied. We observed that Z-TMS treatment resulted in G2/M arrest (95%) of hepatoma cells independent of HCV within 48 hours. Cell cycle progression is orchestrated by cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). CyclinB1/CDK1 complex specifically regulates cell entry into mitosis, and enhances mitochondrial respiration and ATP generation for G2/M transition. In accordance with these observations, we observed a considerable decrease in total CDK1 and a concomitant increase in the cell cycle inhibitor, p21Cip/Waf1, following Z-TMS treatment. The observed p21Cip/Waf1 induction after Z-TMS treatment is resulted in inhibition of CDK1 activities and cell cycle arrest. Akt activation downstream of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway regulates multiple cellular processes such as cell growth, CSC survival, metabolism, angiogenesis and proliferation. Phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 by mTORC2 is required for its hyperactivation and stabilization of its active conformation. We observed a considerable inhibition of Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation following Z-TMS treatment. In addition, Z-TMS induced autophagy that was accompanied by nuclear fragmentation. These properties are especially desirable for the treatment of hard-to-treat drug-resistant cancers.

In conclusion, the results presented here collectively support Z-TMS as a unique potent anti-HCV and anti-tumor drug that exerts its effects by targeting multiple pathways. Z-TMS significantly reduces DCLK1+ CSC populations during hepatic injury, interferes with DCLK1-microtubule dynamics, arrests cell cycle at G2/M phase, promotes autophagy, and causes nuclear fragmentation. Thus, Z-TMS potentially overrides NSCLC resistance to erlotinib because of its unique mechanisms of action.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System, (Minneapolis, Minnesota). We thank Stephenson Cancer Center Pathology Core Laboratory for immunohistochemistry.

Financial Support: This work was partially supported by VA Merit Award and the Frances and Malcolm Robinson Endowed Chair to C.W. Houchen. N. Ali is partially supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from NIH (1P20GM103639NIH) and COMAA Research Fund Seed Grant (OUHSC).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yang JD, Roberts LR. Hepatocellular carcinoma: A global view. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2010;7:448–58. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartosch B, Thimme R, Blum HE, Zoulim F. Hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. Journal of hepatology. 2009;51:810–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–73. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370:1483–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, Chojkier M, Gitlin N, Puoti M, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370:1889–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertino G, Demma S, Ardiri A, Proiti M, Gruttadauria S, Toro A, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Novel Molecular Targets in Carcinogenesis for Future Therapies. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:203693. doi: 10.1155/2014/203693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Padhya KT, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Recent advances in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2013;29:285–92. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835ff1cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauthier A, Ho M. Role of sorafenib in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatology research : the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 2013;43:147–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow AK, Ng L, Lam CS, Wong SK, Wan TM, Cheng NS, et al. The Enhanced metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells with sorafenib resistance. PloS one. 2013;8:e78675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen KF, Chen HL, Tai WT, Feng WC, Hsu CH, Chen PJ, et al. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway mediates acquired resistance to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2011;337:155–61. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasai T, Chen L, Mizutani A, Kudoh T, Murakami H, Fu L, et al. Cancer stem cells converted from pluripotent stem cells and the cancerous niche. Journal of stem cells & regenerative medicine. 2014;10:2–7. doi: 10.46582/jsrm.1001002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majumdar A, Curley SA, Wu X, Brown P, Hwang JP, Shetty K, et al. Hepatic stem cells and transforming growth factor beta in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2012;9:530–8. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita T, Wang XW. Cancer stem cells in the development of liver cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:1911–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI66024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali N, Allam H, May R, Sureban SM, Bronze MS, Bader T, et al. Hepatitis C virus-induced cancer stem cell-like signatures in cell culture and murine tumor xenografts. J Virol. 2011;85:12292–303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05920-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali N, Allam H, Bader T, May R, Basalingappa KM, Berry WL, et al. Fluvastatin interferes with hepatitis C virus replication via microtubule bundling and a doublecortin-like kinase-mediated mechanism. PloS one. 2013;8:e80304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weygant N, Qu D, Berry WL, May R, Chandrakesan P, Owen DB, et al. Small molecule kinase inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 demonstrates potent activity against colorectal and pancreatic cancer through inhibition of doublecortin-like kinase 1. Molecular cancer. 2014;13:103. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung Y, Kim WY. Cancer stem cell targeting: Are we there yet? Archives of pharmacal research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12272-015-0570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou BB, Zhang H, Damelin M, Geles KG, Grindley JC, Dirks PB. Tumour-initiating cells: challenges and opportunities for anticancer drug discovery. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2009;8:806–23. doi: 10.1038/nrd2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lupberger J, Zeisel MB, Xiao F, Thumann C, Fofana I, Zona L, et al. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nature medicine. 2011;17:589–95. doi: 10.1038/nm.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diao J, Pantua H, Ngu H, Komuves L, Diehl L, Schaefer G, et al. Hepatitis C virus induces epidermal growth factor receptor activation via CD81 binding for viral internalization and entry. J Virol. 2012;86:10935–49. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00750-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tresguerres IF, Tamimi F, Eimar H, Barralet J, Torres J, Blanco L, et al. Resveratrol as anti-aging therapy for age-related bone loss. Rejuvenation research. 2014 doi: 10.1089/rej.2014.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh CK, George J, Ahmad N. Resveratrol-based combinatorial strategies for cancer management. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2013;1290:113–21. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Chong T, Wang Z, Chen H, Li H, Cao J, et al. A novel anticancer effect of resveratrol: reversal of epithelialmesenchymal transition in prostate cancer cells. Molecular medicine reports. 2014 doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu B, Zhou Z, Zhou W, Liu J, Zhang Q, Xia J, et al. Resveratrol inhibits proliferation in human colorectal carcinoma cells by inducing G1/Sphase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through caspase/cyclinCDK pathways. Molecular medicine reports. 2014 doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao CL, Huang PI, Tsai PH, Tsai ML, Lo JF, Lee YY, et al. Resveratrol-induced apoptosis and increased radiosensitivity in CD133-positive cells derived from atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;74:219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borriello A, Bencivenga D, Caldarelli I, Tramontano A, Borgia A, Zappia V, et al. Resveratrol: from basic studies to bedside. Cancer treatment and research. 2014;159:167–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38007-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacRae WD, Towers GH. An ethnopharmacological examination of Virola elongata bark: a South American arrow poison. Journal of ethnopharmacology. 1984;12:75–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider Y, Chabert P, Stutzmann J, Coelho D, Fougerousse A, Gosse F, et al. Resveratrol analog (Z)-3,5,4′-trimethoxystilbene is a potent anti-mitotic drug inhibiting tubulin polymerization. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2003;107:189–96. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chabert P, Fougerousse A, Brouillard R. Anti-mitotic properties of resveratrol analog (Z)-3,5,4′-trimethoxystilbene. BioFactors. 2006;27:37–46. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520270104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin HS, Zhang W, Go ML, Choo QY, Ho PC. Determination of Z-3,5,4′-trimethoxystilbene in rat plasma by a simple HPLC method: application in a pre-clinical pharmacokinetic study. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. 2010;53:693–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo JT, Bichko VV, Seeger C. Effect of alpha interferon on the hepatitis C virus replicon. J Virol. 2001;75:8516–23. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8516-8523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson HB, Tang H. Effect of cell growth on hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication and a mechanism of cell confluence-based inhibition of HCV RNA and protein expression. J Virol. 2006;80:1181–90. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1181-1190.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali N, Chandrakesan P, Nguyen CB, Husain S, Gillaspy AF, Huycke M, et al. Inflammatory and oncogenic roles of a tumor stem cell marker doublecortin-like kinase (DCLK1) in virus-induced chronic liver diseases. Oncotarget. 2015;6:20327–44. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iqbal J, McRae S, Banaudha K, Mai T, Waris G. Mechanism of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-induced osteopontin and its role in epithelial to mesenchymal transition of hepatocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:36994–7009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Novelle MG, Wahl D, Dieguez C, Bernier M, de Cabo R. Resveratrol supplementation: Where are we now and where should we go? Ageing research reviews. 2015;21C:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–42. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Souza GR, Molina JR, Raphael RM, Ozawa MG, Stark DJ, Levin CS, et al. Three-dimensional tissue culture based on magnetic cell levitation. Nature nanotechnology. 2010;5:291–6. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kandel ES, Skeen J, Majewski N, Di Cristofano A, Pandolfi PP, Feliciano CS, et al. Activation of Akt/protein kinase B overcomes a G(2)/m cell cycle checkpoint induced by DNA damage. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:7831–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7831-7841.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uehara T, Ainslie GR, Kutanzi K, Pogribny IP, Muskhelishvili L, Izawa T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of fibrosis-associated promotion of liver carcinogenesis. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2013;132:53–63. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dapito DH, Mencin A, Gwak GY, Pradere JP, Jang MK, Mederacke I, et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer cell. 2012;21:504–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caviglia JM, Schwabe RF. Mouse models of liver cancer. Methods in molecular biology. 2015;1267:165–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2297-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sureban SM, Madhoun MF, May R, Qu D, Ali N, Fazili J, et al. Plasma DCLK1 is a marker of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Targeting DCLK1 prevents HCC tumor xenograft growth via a microRNA-dependent mechanism. Oncotarget. 2015;6:37200–15. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang H, Ganguly A, Cabral F. Inhibition of cell migration and cell division correlates with distinct effects of microtubule inhibiting drugs. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:32242–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kavallaris M. Microtubules and resistance to tubulin-binding agents. Nature reviews Cancer. 2010;10:194–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai CK, Jeng KS, Machida K, Lai MM. Association of hepatitis C virus replication complexes with microtubules and actin filaments is dependent on the interaction of NS3 and NS5A. J Virol. 2008;82:8838–48. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00398-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin PT, Gleeson JG, Corbo JC, Flanagan L, Walsh CA. DCAMKL1 encodes a protein kinase with homology to doublecortin that regulates microtubule polymerization. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2000;20:9152–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09152.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim MH, Cierpicki T, Derewenda U, Krowarsch D, Feng Y, Devedjiev Y, et al. The DCX-domain tandems of doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:324–33. doi: 10.1038/nsb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]