Highlights

-

•

GPLA is one rare complication of liver microwave ablation.

-

•

It can be diagnosed with CT scan which shows gas-containing infective focus.

-

•

Patients with gastrectomy may have an increased risk of such infection due to gut flora change.

-

•

To date, data on effectiveness of empirical antibiotic is not convincing.

-

•

Close monitoring following ablation should be prioritised to allow timely intervention and prevent escalation of infection.

Keywords: Clostridium perfringens infection, Gas-containing abscess, Microwave ablation, Liver tumor, Gastrectomy, Prophylactic antibiotic

Abstract

Introduction

Gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess (GPLA) caused by C. perfringens is rare but fatal. Patients with past gastrectomy may be prone to such infection post-ablation.

Presentation of case

An 84-year-old male patient with past gastrectomy had MW ablation of his liver tumors complicated by GPLA. Computerised tomography scan showed gas-containing abscess in the liver and he was managed successfully with antibiotic and percutaneous drainage of the abscess.

Discussion

C. perfringens GPLA secondary to MW ablation in a patient with previous gastrectomy has not been reported in the literature. Gastrectomy may predispose to such infection. Even in high-risk patients, empirical antibiotic before ablation is not a standard of practice. Therefore following the procedure, close observation of patients’ conditions is necessary to allow early diagnosis and intervention that will prevent progression of infection.

Conclusion

Potential complication of liver abscess following MW ablation can never be overlooked. The risk may be enhanced in patients with previous gastrectomy. Early diagnosis and management may minimise mortality and morbidity.

1. Introduction

Image-guided thermal ablation therapy, such as radiofrequency (RF) and microwave (MW) ablations, serves as an alternative to surgery for liver metastasis, especially in patients deemed not suitable for surgery. They aim to destroy tumor cells using heat while doing minimal damage to the surrounding structures or organs. They are relatively safe with low complication rates [1]. Of all major complications, pyogenic liver abscess happens in less than 2% of all hepatic RF ablations. Liver abscess complicated by gas-forming bacterial infections is even less, accounting for 7–24% of all pyogenic liver abscesses [2]. To our knowledge, there has been no case report on C. perfringens GPLA post-MW ablation in patient with gastrectomy. Here, we report this potentially fatal complication associated with MW ablation in a patient with previous gastrectomy and review the literature pertinent to C. perfringens GPLA and the use of prophylactic antibiotic prior to ablation.

2. Presentation of case

An 84 years old male underwent total gastrectomy for his gastric adenocarcinoma in 2014. Past medical history is unremarkable. Subsequent follow-up a year later revealed new onset of 4 liver lesions (segment VIII: 3 cm; segment VII: 2.8 cm; segment VI/VII: 2.3 cm; segment VI: 4.2 cm) consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1). An attempt to treat the tumor with oral chemotherapy was unsuccessful and the patient declined intravenous chemotherapy due to potential side effects. He accepted the option of ultrasound-guided percutaneous MW ablation, which was performed under general anesthesia. No preoperative prophylactic antibiotic was administered. An initial non-contrast CT of the liver was captured to visualise the locations of lesions. Under sterile conditions, a total of seven MW ablations were performed at the tumor sites using Apparatus for Microwave Ablation “AMICA” (Mermaid Medical, Stenløse, Denmark), equipped with a 17-Gauge needle. At segment VIII, two ablations were made at power settings of 60 W for 5 min. Similarly, two ablations of 60 W were made for tumors at segment VII and segment VI for 5 min and 10 min, respectively. Finally, one ablation was performed at 60 W for 10 min at the lesion in segment VI/VII. Ablation margins of 1 cm were achieved for all target lesions. No immediate complications were reported and the patient was sent to the ward with ongoing PRN analgesia.

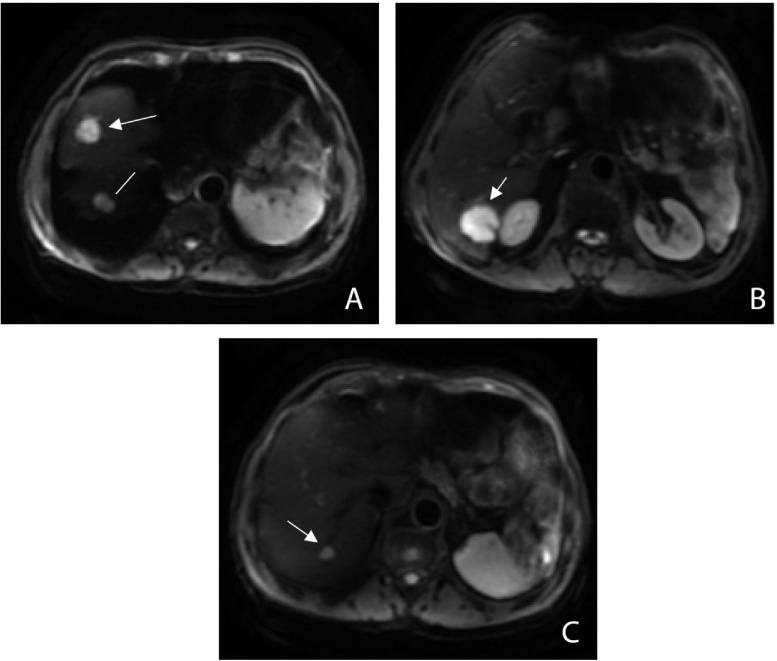

Fig. 1.

Pre-ablation MRI (DWI-sequence) showing the locations of the four liver metastases.

A: A 3-cm (arrow) and 2-cm (line) liver metastases are seen in segment VIII and segment VII, respectively

B: A 3-cm liver metastasis is seen in segment VI (arrow)

C: A 1-cm liver metastasis is seen in segment VI/VII (arrow)

A day following the procedure, patient complained of mild abdominal pain most prominent on right upper quadrant. Vital signs were normal (temperature 37.4; blood pressure 110/60; respiratory rate 17; heart rate 60); full blood count and liver function test were unremarkable. However, on day 2 the patient reported shivering and looked uncomfortable. On examination, he was febrile (39.6), tachycardic (125 bpm), tachypneic (25 bpm) and desaturating at 93%, requiring 2 L of oxygen with nasal prong. Blood pressure was 155/75. His abdomen was soft, non-tender and not distended. Nil percussion or rebound tenderness was elicited. The rest of physical examination was normal. Initial treatment focused on intravenous fluid hydration and administration of broad spectrum antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole). Urinalysis was insignificant while chest x-ray demonstrated no signs of free air. Blood tests showed normal white cell count (4.01 × 109/L), deranged liver enzymes (AST 825; ALT 894) and blood culture yielded positive growth of gram-negative bacilli (Escherichia coli) sensitive to ceftriaxone.

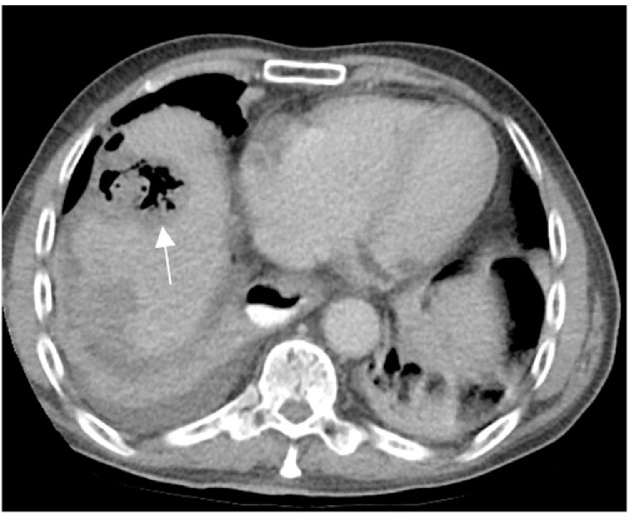

On day 3, the patient remained febrile clinically and had signs of peritonitis on his right abdomen. This led to abdominal computed tomography (CT) with oral contrast, which revealed a gas-containing pyogenic liver abscess (GPLA) within segment VIII where the ablation was performed (Fig. 2). The patient was managed with percutaneous drainage of the abscess, which was positive for Clostridium perfringens and Escherichia coli, and the intravenous antibiotics were switched to a 2-week course of tazocin. Progressively, clinical and infection parameters (temperature, white cell count and C-reactive protein) improved. Later, a progress scan revealed reduction of the diameter of the abscess in segment VIII. Patient was then discharged home on 21/12/2015 with liver drains in situ, which will be removed when output is minimal. He was also given a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (Augmentin DF). No ethic approval by local Institutional Review Board (IRB) is needed for this case report.

Fig. 2.

A gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess is seen at the ablation zone in segment VIII (arrow).

3. Discussion

Incidence of pyogenic liver abscess following ablation may be well-documented. However, C. perfringens GPLA secondary to MW ablation in a patient with previous gastrectomy has not been reported in the literature. C. perfringens is a gram-positive, anaerobic rod often populating in the soil. It can be isolated in gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts of humans. C. perfringens can cause infections such as liver abscess, lung abscess and soft tissue infection. If left untreated, it could escalate rapidly into septicaemia, resulting in life-threatening situation and, ultimately, death in 70% −100% of patients [3]. Risk factors for such deterioration include diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis or immunocompromised state.

The exact mechanism of abscess formation post-ablation is not clearly established. We considered whether bowel injury was responsible for our case but even retrospective reviewed scans do not show any proximity of colon to the treatment site or probe tracks. Therefore, it could most likely arise from the disruption of liver architecture that could occur during MW ablation, thereby connecting bile duct and ablation zone which would provide a pool for growth of enteric bacteria [4]. For our patient, previous history of gastrectomy cannot be overlooked. Stomach provides an acidic environment which kills off microorganisms and removal of this barrier, in return, may increase growth of enteric bacteria in the upper gastrointestinal mucosa [5]. We hypothesise that the previous gastrectomy in this patient might have resulted in retrograde colonisation of the biliary tree with gut organisms.

According to practice guideline, no consensus has been made on the effectiveness of routine prophylaxis due to lack of randomized controlled trials; therefore, the decision to use prophylaxis varies with operators [10]. At our institution, we do not administer empirical antibiotic before hepatic tumor ablation because we argue that it may not be necessary given both the sterile nature of the procedure and the lack of solid evidence supporting the use. However, recent study shows it may be feasible in high risk patients such as elderly, those with diabetes, bilioenteric anastomosis (BEA) or other biliary issues and tumor positioned near central bile duct [11]. Retrospectively, taking into account of our patient’s advanced age and past history of gastrectomy, we wonder whether such complication can be avoided should prophylaxis was given prior to the procedure. Nevertheless, Shibata and colleagues concluded that, albeit trend appears to favour some sort of prophylaxis, lack of antibiotic do not predispose to the development of infection [12]. We believe that until more evidence proving the effectiveness of empirical antibiotic surfaces, clinicians should instead be mindful of such complication and be focused on careful post-treatment monitoring to allow early diagnosis and intervention.

Rapid diagnosis of patients with C. perfringens GPLA is paramount in improving patients’ clinical outcomes. The initial presentation can be variable with abdominal pain and fever most frequently reported [6]. In the settings of MW ablation, the nonspecific symptoms could prove challenging to the diagnosis as it could mimic post-ablation syndrome. This was clearly reflected in our case whereby his complaint of mild right upper quadrant pain on day 1 post-ablation was not immediately addressed with appropriate workup. The most reliable clinical investigation that could aid in diagnosis is appearance of gas-forming liver abscess on imaging [7]. The presence of gram-positive rod on blood culture may be helpful but should not always be relied upon in the diagnosis of C. perfringens GPLA because it does not always reflect the microbiology of the GPLA, as highlighted in our case [8]. Immediate treatment of patient can be life-saving if there is sufficient clinical ground to suspect C. perfringens GPLA. Such circumstance warrants aggressive managements which include percutaneous or surgical evacuation of infectious focus, administration of relevant antibiotics and supportive measures to sustain organ functions [9]. In hindsight, the early administration of empirical antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole) and aggressive abscess drainage might explain the excellent prognosis in our patient.

4. Conclusion

Overall, our case illustrates a rare complication of MW ablation in a patient with previous gastrectomy. Patients with previous gastrectomy may be prone to such infection as a result of gut flora alteration. While administration of prophylactic antibiotic may be necessary in patients with possible risk factors for liver abscess, the efficacy of prophylactic antibiotic before hepatic ablation in general remains sceptical. Instead, clinicians should be mindful of such complication and should closely monitor these patients following procedure. It is imperative to follow diagnosis with aggressive management by the means of infection drainage, intravenous antibiotics and supportive measures.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

No ethic is required for this research.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required and patient identifying knowledge was not presented in this report.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Lee Kyang – main author.

Thamer Bin Traiki and Nayef Alzahrani – involved in editing of paper and data collection.

David L Morris – involved in study design and patient recruitment.

Guarantor

Lee S Kyang, Nayef AlZahrani, David L Morris.

References

- 1.Sun A.-X., Cheng Z.-L., Wu P.-P., Sheng Y.-H., Qu X.-J., Lu W. Clinical outcome of medium-sized hepatocellular carcinoma treated with microwave ablation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21(10):2997–3004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee H.-L., Lee H.-C., Guo H.-R., Ko W.-C., Chen K.-W. Clinical Significance and Mechanism of Gas Formation of Pyogenic Liver Abscess Due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;12(6):2783–2785. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2783-2785.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan M.S., Ishaq M.K., Jones K.R. Gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess with septic shock. Case Rep. Crit. Care. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/632873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi D., Lim H.K., Kim M.J., Kim S.J., Kim S.H., Lim J.H. Liver abscess after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinomas: frequency and risk factors. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005;184(6):1860–1867. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.6.01841860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C., Tsang Y.-M., Hsueh P.-R., Huang G.-T., Yang P.-M., Sheu J.-C. Bacterial infections associated with hepatic arteriography and transarterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999;29(1):161–166. doi: 10.1086/520146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogl T.J., Farshid P., Naguib N.N.N., Darvishi A., Bazrafshan B., Mbalisike E. Thermal ablation of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: radiofrequency, microwave and laser ablation therapies. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2014;119(7):451–461. doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law S.-T., Lee M.K. A middle-aged lady with a pyogenic liver abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens. World J. Hepatol. 2012;4(8):252–255. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i8.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahimian J., Wilson T., Oram V., Holzman R.S. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;39(11):1654–1659. doi: 10.1086/425616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong V.H., Yong A.M., Wahab A.Y. Gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess. Singapore Med. J. 2008;49(5):e123–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatesan A.M., Kundu S., Sacks D., Wallace M.J., Wojak J.C., Rose S.C. Practice guideline for adult antibiotic prophylaxis during vascular and interventional radiology procedures. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010;21(11):1611–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatia S.S., Spector S., Echenique A., Froud T., Suthar R., Lawson I. Is antibiotic prophylaxis for percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of primary liver tumors necessary? results from a single-Center experience. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;38(4):922–928. doi: 10.1007/s00270-014-1020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beddy P., Ryan J.M. Antibiotic prophylaxis in interventional radiology—anything new? Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016;9(2):69–76. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]