Highlights

-

•

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is a rare but serious condition, regardless of the treatment dose or thromboprophylaxis.

-

•

A 55-year-old man, who underwent portless endoscopic radical nephrectomy, was diagnosed with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia.

-

•

Surgeons should know that HIT is diagnosed based on clinical and serologic findings.

Abbreviations: HIT, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; VTE, venous thromboembolism; UFH, unfractionated heparin; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; AUA, American Urological Association

Keywords: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, Thromboprophylaxis, Urologic surgery, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a rare but serious condition due to heparin use for treating thromboprophylaxis, regardless of the dosage. Here, we present a case of non-immune thrombocytopenia caused by thromboprophylaxis for urological surgery, which is sometimes difficult to discriminate from immune-mediated thrombocytopenia.

Presentation of case

A 55-year-old man with renal cancer underwent portless endoscopic radical nephrectomy through a single small incision and was subsequently administered unfractionated heparin as well as mechanical devices to prevent venous thromboembolism. On postoperative day 2, a subcutaneous hemorrhage developed around the surgical site and the lower abdomen, and the platelet count simultaneously decreased to 50% of the baseline value. We suspected HIT and immediately conducted the 4Ts score examination. The 4Ts score was 3 points (low probability), and the result of the platelet factor 4-heparin complex antibody assay was negative. The patient was diagnosed with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia. We took precaution by discontinuing heparin, which fortunately did not result in any adverse effects, and this led to platelet count normalization.

Discussion

Due to the rarity of HIT, it is difficult to distinguish HIT from non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia.

Conclusion

This article emphasizes that early and accurate diagnosis of postoperative thrombocytopenia is important for accurate therapy. Hence, all surgeons should know that the HIT diagnosis is based on clinical and serologic findings.

1. Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is one of the most common causes of perioperative nonsurgical death. The American Urological Association published a statement on perioperative VTE prevention for urological surgeries, in which unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) are recommended for thromboprophylaxis [1]. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a rare but serious adverse event that occurs in 1–5% of patients who are administered a perioperative thromboprophylactic dose of heparin. The dose is typically lower than that for therapeutic use, but the incidence of HIT is reported to be more frequent [2]. HIT can lead to thromboembolic complications, including pulmonary thromboembolism, ischemic limb necrosis, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke [3]. The two types of HIT are distinguishable by pathophysiologic mechanisms and clinical characteristics. Type 1 HIT arises via a non-immunologic mechanism within a few days after exposure to heparin. It is characterized by a mild thrombocytopenia that requires careful monitoring but typically not the cessation of heparin therapy [4]. Type 2, i.e. immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, is caused by the development of IgG antibodies directed against a complex of PF4 and heparin, and it is characterized by a major decrease in platelet count and paradoxical hypercoagulable state caused by platelet activation and associated thrombin generation [5]. Thrombosis occurs more frequently in patients with type 2 HIT, and type 2 requires more severe management than type 1. Therefore, the term “HIT” has been more generally used to describe type 2 but not type 1. Overlooking or misdiagnosing HIT, conversely, may result in serious adverse events or exposure of thrombocytopenic patients to alternative anticoagulants and unnecessary suspension of heparin. Herein, we report a case of non-immune-mediated thrombocytopenia caused by the thromboprophylactic use of heparin after urological surgery.

2. Presentation of case

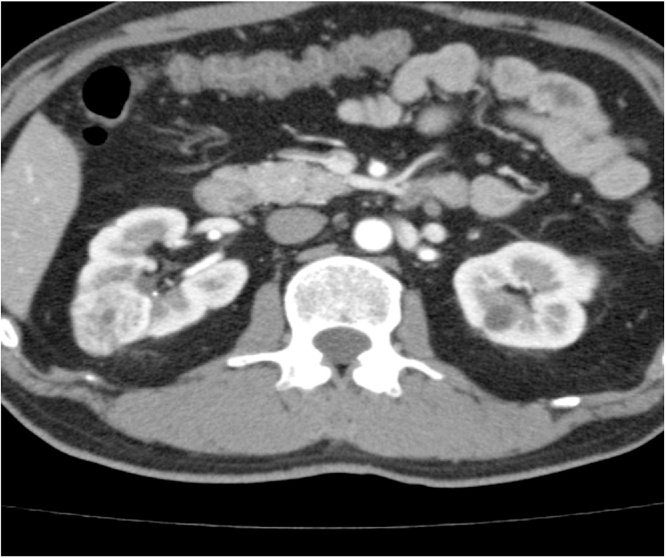

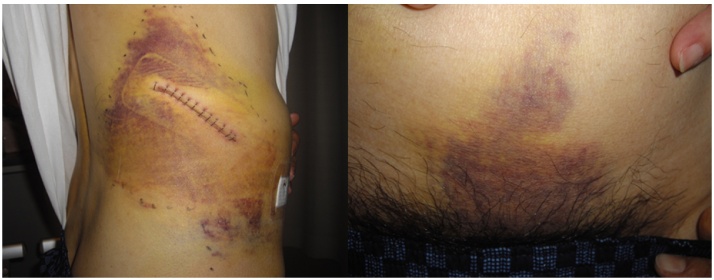

A 55-year-old man was referred to our hospital for the treatment of a right renal tumor. Computed tomography (CT) showed a 3.0-cm hypervascular tumor without any metastasis in his right kidney (Fig. 1). The patient had not received heparin treatment in the past. A portless endoscopic radical nephrectomy through a single small incision was performed, resulting in 40 mL of estimated blood loss, and the histological diagnosis was pT1a, clear cell renal cell carcinoma [6], [7]. The patient was prescribed mechanical thromboprophylaxis until he achieved full ambulatory status, and 5000 units of UFH were administered twice a day subcutaneously, initiated 3 h after surgical closure. He was not prescribed any other drugs (i.e., chemotherapy, linezolid, or bortezomib) that could cause thrombocytopenia by non-immune mechanisms perioperatively. On postoperative day 2, a subcutaneous hemorrhage developed around the surgical site and the lower abdomen (0 points for the Timing and Thrombosis elements of the 4Ts score) (Fig. 2). His platelet count decreased to 50% of the baseline value (nadir, 49 × 109/L, 2 points for the Thrombocytopenia element of the 4Ts score) after a secondary injection of 5000 units of UFH, although it was 164 × 109/L, which was within the normal level, preoperatively. There were other possible causes for thrombocytopenia, including the consumption of platelets due to surgical invasion (1 point in the oTher element of the 4Ts score). The 4Ts score, which is the most reliable tool for clinically suspected HIT, was 3 points, equating to a low probability level, and the patient did not have skin lesions at the heparin injection sites or an acute systemic reaction [3]. The platelet factor 4 (PF4)-heparin complex antibody assay was negative. Multidetector-row CT and color Doppler ultrasonography did not show any thrombosis. Based on these findings, the patient was not diagnosed with HIT, but he was diagnosed with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia due to heparin. We decided to discontinue anticoagulation therapy because the patient was fully ambulatory, and the platelet count promptly increased to 173 × 109/L after discontinuation of UFH.

Fig. 1.

A computed tomography showed a 3 × 3 cm enhanced solid lesion in the middle of the right kidney.

Fig. 2.

Subcutaneous hemorrhage around the surgical site and the lower abdomen.

3. Discussion

Immune-mediated HIT is an adverse drug reaction that can lead to devastating thromboembolic complications, even when using heparin for perioperative thromboprophylaxis. It occurs when a complex between IgG antibodies and PF4-heparin forms. The antibodies activate platelets by binding to the FcγIIa receptor, resulting in systemic thrombosis and consumptive thrombocytopenia [8]. On the other hand, the prevention of thromboembolism associated with surgical procedures is a necessary consideration for surgeons by using anti-coagulation agents, such as heparin, aspirin, and warfarin, because thromboembolism is a perioperative life-threatening event [9]. Accordingly, the AUA and American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend prescription of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in addition to mechanical devices postoperatively [1], [3]. In such a situation, we encountered a case of non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia, which we distinguished from HIT, in perioperative thromboprophylaxis.

The diagnosis of HIT requires a combination of clinical assessment and immunoassay results. The 4Ts score, which is currently considered the most reliable tool, is derived using 4 elements: the degree of Thrombocytopenia, Timing of platelet count decrease or thrombosis, Thrombosis or other clinical sequelae, and oTher causes of thrombocytopenia [3]. Cuker et al. reported a systemic review and meta-analysis of 13 eligible studies evaluating the predictive value of the 4Ts scoring system. The negative predictive value of a low probability 4Ts score (≤3) was 0.998 (95% CI, 0.970–1.000), and the positive predictive values of intermediate and high probability (≥4) 4Ts scores were 0.14 (0.09–0.22) and 0.64 (0.40–0.82), respectively [8]. Thus, they proposed that a low probability 4Ts score is a way to exclude HIT, and alternative diagnoses, including non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia, should be considered for patients with low 4Ts scores [10]. Additionally, they described the possibility of missing patients with true HIT despite a low probability 4Ts score.

To confirm the diagnosis of HIT, immunoassays are also required, of which there are two major categories: functional assays that detect evidence of platelet activation by HIT antibodies and antigen assays that detect the presence of HIT antibodies. Functional assays, such as the heparin-induced platelet activation and serotonin release assays, have high sensitivity and specificity. However, they require radioisotope and reactive donor platelets, which are reagents that are unfeasible for most clinical laboratories owing to the time and labor involved. Consequently, such assays are available to the majority of clinicians only as “send-out” tests and do not yield results in a timeframe necessary to inform initial clinical decision-making [3], [10]. We used the antigen assay, for which the sensitivity is very high while the specificity is moderate, because it was the only available assay in our institute.

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends the use of argatroban, lepirudin, or danaparoid, rather than further use of heparin, LMWH, or initiation/continuation of a vitamin K antagonist, with or without thrombosis (Grade 1C), when treating HIT [3]. In contrast, non-immune-mediated thrombocytopenia is usually mild and transient. It is a benign condition not associated with risk thrombosis. The present case was diagnosed as non-immune-mediated thrombocytopenia because of the results of 4Ts score and immunoassay. Although our patient’s platelet levels promptly recovered upon discontinuation of UFH with monitoring and mechanical thromboprophylaxis, there might be no need to discontinue heparin for non-immune-mediated thrombocytopenia.

A comprehensive MEDLINE search resulted in only 3 cases reports within the medical literature of HIT during urological surgery [8], [11], [12]. Consequently, urologists are not usually familiar with the management of and the principles for treating this condition. One reported case involved transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia, and the 4Ts score and immunoassays were not implemented for diagnosis. The other cases involved a partial nephrectomy for renal cancer and Fournier gangrene. HIT was detected in those cases after diagnosis of a bilateral adrenal hemorrhage after more than 5 days of heparin administration without calculation of the 4Ts score. One of these 3 cases were diagnosed after PF4-heparin complex antibody detection. However, the others were diagnosed without the immunoassays.

The implementation of diagnostic methods for HIT appears to be insufficient. Surgeons should consider HIT when heparin is used for perioperative thromboprophylaxis and perform the necessary examinations immediately if suspected. Otherwise, this serious complication due to heparin use might be overlooked.

4. Conclusion

We diagnosed the patient described here with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia and not HIT because of the 4Ts score and negative antigen assay results. This article emphasizes the need for early and accurate diagnosis of postoperative thrombocytopenia in order to accurately treat patients. Hence, all surgeons should know the HIT diagnosis is based on clinical and serologic findings.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to be declared.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Ethic approval not required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Author contribution

Kenichi Hata is first and corresponding author of this article. Takahiro Kimura and Shin Egawa critically revised this article. Gen Ishii and Masayasu Suzuki contributed to the acquisition of data.

Guarantor

Kenichi Hata.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

References

- 1.Forrest J.B., Clemens J.Q., Finamore P., Leveillee R., Lippert M., Pisters L. AUA best practice statement for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing urologic surgery. J. Urol. 2009;181:1170–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson H., Davidson S., Keeling D. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: second edition. Br. J. Haematol. 2012;159:528–540. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linkins L.A., Dans A.L., Moores L.K., Bona R., Davidson B.L., Schulman S. Treatment and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed.: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e495S–530S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong B.H., Berndt M.C. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blut. 1989;58:53–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00320647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martel N., Lee J., Wells P.S. Risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2005;106:2710–2715. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edge S.B., Compton C.C. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kihara K., Kageyama Y., Yano M., Kobayashi T., Kawakami S., Fujii Y. Portless endoscopic radical nephrectomy via a single minimum incision in 80 patients. Int. J. Urol. 2004;11:714–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winter A.G., Ramasamy R. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia following partial nephrectomy—a case report. F1000 Research. 2014;3:24. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.3-24.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turpie A.G., Bauer K.A., Eriksson B.I., Lassen M.R. Fondaparinux vs enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in major orthopedic surgery: a meta-analysis of 4 randomized double-blind studies. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002;162:1833–1840. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuker A., Gimotty P.A., Crowther M.A., Warkinten T.E. Predictive value of the 4Ts scoring system for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2012;120:4160–4167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-443051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawada T., Watanabe T., Oogo Y., Iwasaki A., Isizuka E. A case of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia after transurethral resection of prostate during anticoagulant therapy. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;92:702–705. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol1989.92.702. (in Japanese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tattersall T.L., Thangasamy I.A., Reynolds J. Bilateral adrenal haemorrhage associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopaenia during treatment of Fournier gangrene. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;201:4. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]