Abstract

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare clinically polymorphic tumor that mimics both benign and malignant conditions. It presents with dermal or subcutaneous nodules on the extremities in young adults. We present here a case of epithelioid sarcoma of the inguinal region infiltrating the femoral vessels. Biopsy is diagnostic and good histopathological evaluation is critical in management.

Keywords: Inguinal mass, Epithelioid sarcoma, Vascular invasion, Surgical resection

Introduction

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare clinically polymorphic tumor that mimics both benign and malignant conditions. We present here a case of epithelioid sarcoma of the inguinal region infiltrating the femoral vessels. Unlike other sarcomas, ES demonstrates lymphatic and not hematogenous metastasis. Excision biopsy is diagnostic and good histopathological evaluation is critical in management. The aim of the article is to increase awareness of this rare location of a tumor, which can evade diagnosis. A high index of suspicion is necessary for early diagnosis and good outcome in patients with epithelioid sarcoma.

Case Report

A 20-year-old male presented with a painless, progressive left inguinal swelling for 4 years. Examination revealed a large ill-defined groin mass and non-pitting edema from the groin to the foot. The peripheral pulses were normal. Other systemic and general examinations were normal. He did not have any other medical problems or family history of malignancy.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a retroperitoneal mass in the left iliac fossa (Figs. 1 and 2) with para-iliac nodes adherent to the psoas. It was encasing and compressing the iliac vein, the femoral vein, and the left ureter. A core biopsy of the swelling was reported as a poorly differentiated neoplasm with low-grade malignant potential, probably of vascular origin. The complete metastatic workup was negative. Neoadjuvant chemo was planned with the initial diagnosis of a poorly differentiated neoplasm following a multi-disciplinary tumor board meeting involving radiology, radiotherapy, and medical oncology with the aim of tumor cytoreduction which may allow less radical surgical resection and immediate treatment of micrometastases. However, the tumor did not regress after 5 cycles of ifosfamide and vincristine. With this indication of poor effectiveness of chemotherapy/radiotherapy, en bloc resection of the left ilioinguinal mass was performed. Arterial reconstruction (left common iliac to common femoral artery end-to-end bypass) was done with a prosthetic (polytetrafluoroethylene) graft. The ureter and periureteral sheath were dissected free. Lymphadenectomy was performed simultaneously. Postoperatively, the patient had a perigraft seroma which was managed conservatively. He was discharged on the 15th postoperative day. His biopsy was reported as epithelioid sarcoma (classic type), one of three regional lymph nodes with metastatic tumor. Surgical margins were negative with no perineural invasion. Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for CD34, D2-40, cytokeratin, and vimentin and negativity for CD31. He was planned for adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin-ifosfamide.

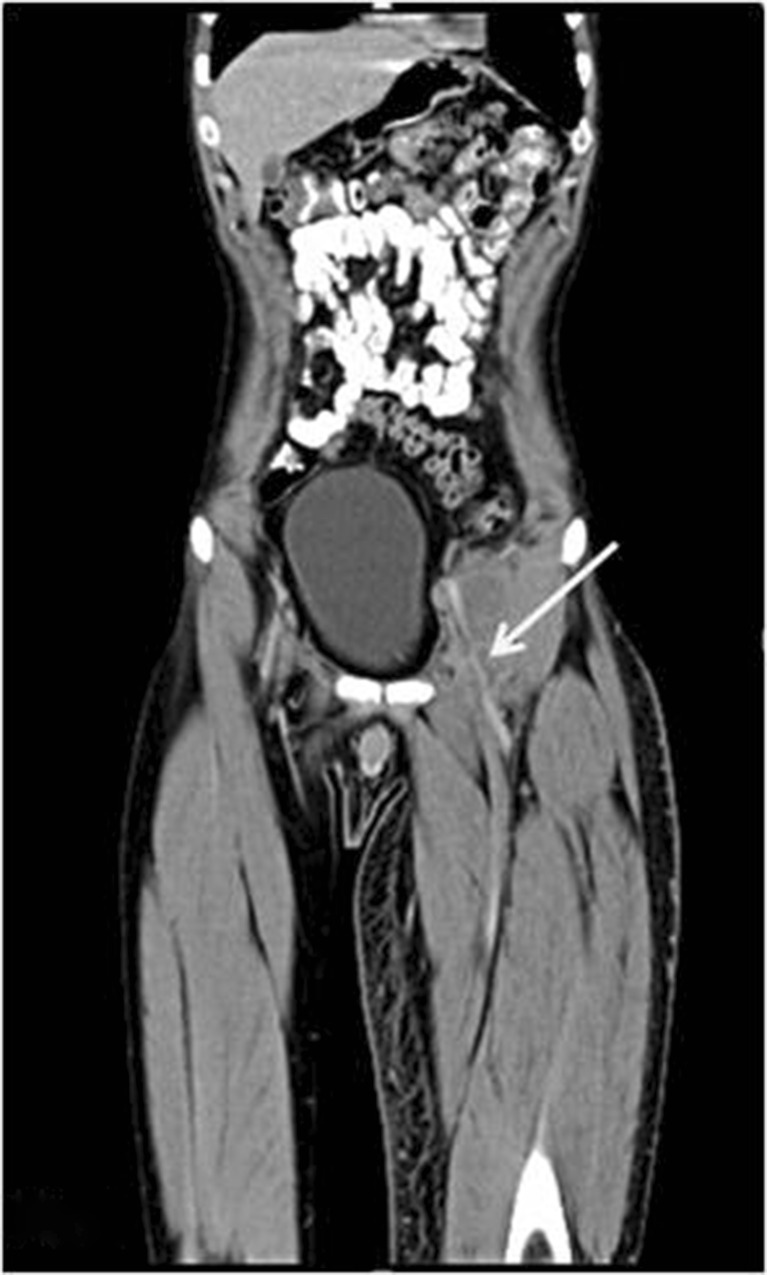

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography (coronal cuts) of the abdomen showing a predominantly hypodense retroperitoneal mass extending into the left inguinal region encasing the femoral vessels (arrow)

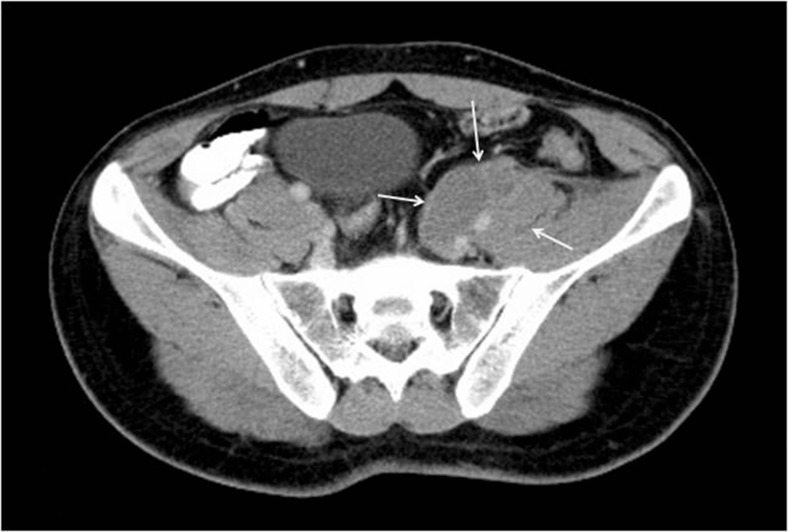

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography (axial cuts) of the abdomen showing the mass adherent with the left iliopsoas with vessel involvement (arrows)

Discussion

Malignant inguinal tumors are rare, with liposarcomas of the cord being the commonest in adults [1]. ES are diagnosed in 1 % of sarcomas [2]. They were first described by Enzinger [3]. There are two subtypes: the commoner distal or conventional type affects the upper and lower extremities. These are painless, superficially located, slow-growing, solitary or confluent multinodular tumors in the dermis or soft tissues. They mimic warts, cysts, granulomas, or carcinomas. Perivascular location or vascular infiltration is rare. They grow along fascial planes, aponeuroses, and tendon sheaths. About 26 % of patients present with multifocal tumors or metastases [4]. Though less common, the proximal-type ES is more aggressive. The sites of involvement differ; the latter affects the pelvic, perineal, and genital regions. Perivascular location is not reported [5–11].

Imaging reveals a predominantly solid, multinodular diffusely infiltrative tumor with multiple areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. There are no diagnostic imaging features for ES. Core and fine-needle aspiration biopsy may fail to establish diagnosis. A high degree of suspicion for malignancy should be maintained based on the clinical and imaging features [12, 13].

Histopathology following surgical resection is diagnostic: grossly, it is a glistening, gray-tan tumor; microscopy shows nodular infiltration and central necrosis. The tumor cells are large, polygonal or rounded with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesiculous nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Proximal ES has excess cytologic atypia, rhabdoid features and lacks a granuloma-like pattern (the latter is occasionally present in distal ES) [14]. Both subtypes have similar immunohistochemical (IHC) staining: positive for cytokeratins, vimentin, and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). Desmin and CD34 staining are variable. Smooth muscle actin, CD31, S100, HMB-45, and neurofilament are negative [6]. A loss of function of the SMARCB1 gene (BAF47, INI1, or hSNF5) is found in 80 % patients. INI1 staining can be used to diagnose ES. Various pathological subtypes are described: angiomatoid, inflammatory granuloma, epithelial tumor, achromic melanoma, epithelioid sclerosing fibrosarcoma [5], and epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma [14]. Differential diagnosis includes angiogenic tumors (hemangioma/angiosarcoma), synovial sarcoma, extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, or malignant fibrous histiocytoma.

Prognosis is dependent on age, tumor size, grade (tumors larger than 5 cm are aggressive), location (deeper tumors in the limb are more aggressive), microscopic pathology (necrosis, vascular invasion), number of local recurrences, and metastases [15, 16]. Females have more favorable outcomes than males. The 5-year survival is 50–70 % and the 10-year survival rate is 42–55 %. Children have better outcomes (5-year survival rate 65 %) possibly due to lower lymphatic spread/metastasis [2, 15, 17].

Surgical resection with wide margins is the treatment of choice [16]. Sentinel node biopsy is recommended due to the propensity of lymph node metastasis in patients where nodal metastasis is not evident. Our patient did not undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy as the large size of the tumor and clinically evident lymph node metastasis necessitated a radical excision of the tumor with the surrounding lymph nodes and lymphatics. Complete excision may be complicated by tumor proximity to joints—occasionally necessitating amputation. Chemo-/radiotherapy are used for locally advanced, inoperable, recurrent, or metastatic disease [17] with relatively worse outcomes. Our patient was young and he was advised adjuvant therapy due to the small but potential role of this therapy in node-positive disease to reduce the risk of tumor bed recurrence. Doxorubicin, ifosfamide, gemcitabine, and pazopanib are used. Chemotherapy may not confer a survival advantage. Brachytherapy has been used with limited success. Newer agents targeting mTOR and c-MET signalling pathways are being studied [7]. Our patient was advised three monthly clinical follow-up with repeat imaging at each visit for 2 years. There was no evidence of recurrence at the last follow-up. The arterial reconstruction was patent and his foot pulses were palpable. The venous edema had resolved. His long-term survival remains to be followed up.

Conclusion

Epithelioid sarcoma is uncommon; a perivascular location is rare. Histopathological study following surgical resection is diagnostic; en bloc resection with adjuvant chemotherapy is the treatment of choice.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.McCormick D, Mentzel T, Beham A, Fletcher CD. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 32 cases suggesting a better prognostic subgroup among pleomorphic sarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:1213–1223. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814–819. doi: 10.5858/133.5.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enzinger FM. Epithelioid sarcoma. A sarcoma simulating granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970;26:1029–1041. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197011)26:5<1029::AID-CNCR2820260510>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos GD, Pritchard DJ, Reiman HM, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma. An analysis of fifty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:862–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wegmann W, Waibel P, Widmer LK. Stenosing of the femoral artery by an epithelioid sarcoma. Vasa. 1980;9(3):227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, Shmookler BM, Fetsch JF. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(8):934–942. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imura Y, Yasui H, Outani H, Wakamatsu T, Hamada K, Nakai T, Yamada S, Myoui A, Araki N, Ueda T, Itoh K, Yoshikawa H, Naka N. Combined targeting of mTOR and c-MET signaling pathways for effective management of epithelioid sarcoma. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:185. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akpinar F, Dervis E, Demirkesen C, Akpinar AC, Ergun SS. Epithelioid sarcoma of the extremities. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(2):168–170. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.129409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rekhi B, Gorad BD, Chinoy RF. Clinicopathological features with outcomes of a series of conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcomas, diagnosed over a period of 10 years at a tertiary cancer hospital in India. Virchows Arch. 2008;453(2):141–153. doi: 10.1007/s00428-008-0639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livi L, Shah N, Paiar F, Fisher C, Judson I, Moskovic E, Thomas M, Harmer C. Treatment of epithelioid sarcoma at the Royal Marsden Hospital. Sarcoma. 2003;7(3–4):149–152. doi: 10.1080/13577140310001644760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf PS, Flum DR, Tanas MR, Rubin BP, Mann GN. Epithelioid sarcoma: the University of Washington experience. Am J Surg. 2008;196(3):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna SL, Kaste S, Jenkins JJ, Hewan-Lowe K, Spence JV, Gupta M, Monson D, Fletcher BD. Epithelioid sarcoma: clinical, MR imaging and pathologic findings. Skelet Radiol. 2002;31(7):400–412. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imaizumi S, Morita T, Ogose A, Hotta T, Kobayashi H, Ito T, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma mimicking chronic hematoma: value of magnetic resonance imaging in differential diagnosis. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7:33–37. doi: 10.1007/s776-002-8410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillou L, Wadden C, Coindre JM, et al. “Proximal type” epithelioid sarcoma, a distinctive aggressive neoplasm showing rhabdoid features. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:130–146. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199702000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chase DR, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid sarcoma: diagnosis, prognostic indicators and treatment. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9(4):241–263. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198504000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, Veth RP, Ten Heuvel SE, Suurmeijer AJ, Hoekstra HJ. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107(3):606–612. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National comprehensive cancer network: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Soft tissue sarcoma. Version 2.2014 [DOI] [PubMed]