Abstract

Most behavior change trials focus on outcomes rather than deconstructing how those outcomes related to programmatic theoretical underpinnings and intervention components. In this report, the process of change is compared for three evidence-based programs’ that shared theories, intervention elements and potential mediating variables. Each investigation was a randomized trial that assessed pre- and post- intervention variables using survey constructs with established reliability. Each also used mediation analyses to define relationships. The findings were combined using a pattern matching approach. Surprisingly, knowledge was a significant mediator in each program (a and b path effects [p<0.01]). Norms, perceived control abilities, and self-monitoring were confirmed in at least two studies (p<0.01 for each). Replication of findings across studies with a common design but varied populations provides a robust validation of the theory and processes of an effective intervention. Combined findings also demonstrate a means to substantiate process aspects and theoretical models to advance understanding of behavior change.

Keywords: Behavior change, Mediation, Peer-led

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge about how healthy lifestyles can prevent illness has outpaced effective means to assist people in living health lives [1]. That limitation is not due to lack of research, and contributions have come from diverse disciplines, such as health promotion, behavioral economics, psychology, decision analysis, and sociology. However, progress may have been constrained due to a focus on outcomes rather than deconstructing how change occurred [2–4]. Our group has studied a series of behavior change interventions that use a shared format and theoretical structure. All had documented efficacy in randomized controlled trials [5–10], and for each, specific program components were related to behavioral endpoints [11–13]. Comparing their observed patterns of findings presents a means to assess theories of behavior change and validate an effective intervention format.

PROGRAM THEORY, DESIGN, AND DECONSTRUCTION

Conceptual theory

When designing an intervention, the theoretical foundations determine variables to target to achieve the desired results. Aspects of three theories informed our interventions: the Health Belief Model (HBM) [14], the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [15], and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [16]. Together, they comprised the interventions’ conceptual theory [17]. The HBM suggests that a person integrates benefits of a behavior with barriers and the severity and susceptibility to adverse effects of not performing it. Where the HBM describes a balance sheet of perceived threat and net benefit, the TPB begins to integrate norms of what others do. The TPB also adds the concept of self-efficacy or one’s belief that he or she can accomplish a specific task. Although not often mentioned, both models have a role for knowledge, as it is integral to the constructs of severity, susceptibility, and peer norms. In addition, each individual brings other factors that influence outcomes, such as cultural background, psychological state and traits, and prior experiences.

SCT extends beyond the individual and adds a dynamic reciprocal interaction between an individual and the environment, including directly observing the actions of others. The interaction is typically represented by a triadic relationship among personal factors (such as thoughts, outcome expectancies, skills, and self-efficacy); the environment (e.g., cues and vicarious experiences); and the behavioral outcomes of interest. SCT also includes the importance of goals, with monitoring progress toward those goals affecting self-efficacy and subsequent behavior [18].

Action theory

The action theory defines how the conceptual theory’s targeted variables will be altered [17]. All of our programs shared the same underlying action theory or intervention processes: (1) peer-led direct instruction to affect knowledge, abilities, and norms and (2) explicit goal setting and monitoring at an individual and team level.

Peer-led direct instruction

Using peers to facilitate sessions has several advantages. Peer leaders have intrinsic credibility and ability to tailor the discussion with relevant examples [19]. They also promote a sense of shared norms and social support [20]. In other settings, peers have been shown to be as effective as professionally delivered formats [21]. Although a potential downside is the need to recruit and train peer leaders, each program used a scripted format that minimized training and even allowed that role to be rotated among team members.

The scripted curriculum required a design to maximize learning, and direct instruction provided those guidelines [22]. In general, direct instruction follows a specific sequence [23]. First is a statement about learners’ end objectives or what they will be able to do following the lesson. The second is to establish content relevance and/or how the lesson builds on preceding material. Next is providing information and having learners practice, reformulate, and personalize it. Lastly, learning is reviewed, and goals are set and disclosed, with additional motivation coming from the session’s momentum, self-efficacy of the practice, and feedback when reporting on progress. Although primarily designed as pedagogy for younger learners, direct instruction also aligns well with principles of adult learning [24, 25]. Experienced educators often dislike direct instruction’s more prescriptive format, as their styles differ, and they value their personal creativity as educators and students’ discovering the content, rather than upfront objectives. However, for our peer leaders, the limited preparation and easy-to-follow format were ideal.

Individual and team goal setting and self-monitoring

Goal setting is a component of many behavior change programs, with its positive impact relating to social disclosure enhancing commitment, receiving feedback and enhancing self-efficacy [26]. For each of program, goals were set each session and monitored at an individual and team level.

A focus for our interventions was formation of teams, groups of four to seven members who work through the curricula together. We use the term team rather than group, as teams are characterized by a sense of shared commitment and mutual accountability [27, 28]. With a team, the goal-reward structure can be individual, shared, or both [29]. Team level rewards promote mutual accountability and cooperation; however, they may reduce personal responsibility. Having both levels operating simultaneously can augment productivity [30], and that hybrid system was used with our programs’ teams.

Mediation analysis to combine action and conceptual theories

Mediation analysis is a means to assess the hypothetical relationships across intervention processes, targeted variables, and outcomes. It provides an explicit check on whether a program affected the intermediate variables and whether the purported theoretical relationship of those variables to outcomes holds.

A basic mediation model is shown in Fig. 1, where the intervention (X) is presumed to affect the mediator (M), and that path (a) represents a test of the action theory. The mediator affects the outcome or dependent variable (Y), and that mediation path (b) represents a test of the conceptual theory [31]. In an idealized program, both the a and b paths are confirmed. That is, the program changed the mediator, and that change related to the outcome. However, that ideal situation does not always apply. An intervention might affect the mediating variables in the absence of significant effects on outcomes, a finding that suggests that the conceptual theory was faulty. Conversely, outcomes could be altered without a change in the presumed mediating variables, indicating that change was influenced by other unmeasured intermediate variables. Mediation analysis informs intervention design, and its application is becoming more frequent in understanding interventions [32, 33].

Fig 1.

Basic mediation model

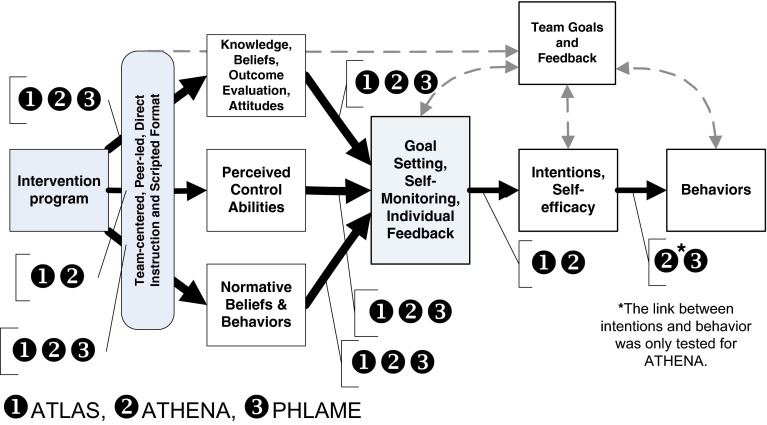

A strength of our studies was application of mediation analyses to similar underlying behavior change models. Figure 2 depicts the programs’ components and theoretic structure. Comparing the pattern of which paths were confirmed across studies provides information about the validity of their structure.

Fig 2.

Integrated action and conceptual model components. Some components modified from Fishbein M, Cappella JN. J Commun. 2006;56:S1-S17 (with permission)

Lacking in Fig. 2 are elements of the built environment and external cues that enhance behavior change, aspects that are prominent components of ecological models [34]. However, robust environmental components were absent from our programs to avoid diffusion to the control condition. Accordingly, environmental features have a limited role in our interventions’ construction or theoretical underpinnings. Adding those elements would be expected to enhance the programs’ efficacy.

OVERVIEW OF THREE EVIDENCE-BASED PROGRAMS

The initial behavior change intervention was entitled Athletes Training and Learning to Avoid Steroids (ATLAS) [5]. Funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), this prospective randomized trial evaluated a sport team-centered drug prevention/health promotion program for high school football players. The scripted curriculum was designed to be delivered during the sport season and integrated into a team’s usual practice activities. The coach facilitated the program, with the entire team meeting as a large group, partitioned into six-member squads, with one individual per squad designated as the student leader. The program was formatted as a playbook with explicit lesson plans and a programmed text for the coach and squad leaders, while other team members used corresponding workbooks. The majority of the ten, 60-min weekly sessions was peer-led, as the squads of student athletes worked through activities to alter their knowledge, skills, and attitudes about anabolic steroid and other performance-enhancing substance use.

That general structure was replicated in the NIDA-funded Athletes Targeting Healthy Exercise and Nutrition Alternatives (ATHENA) program, with the curriculum content modified to address risk and protective factors relevant to young women’s use of harmful body-shaping actions [6]. For both programs, from the athletes’ perspective, they were about improving sport performance, while the hidden curriculum was deterring harmful actions and enhancing life skills. Both ATLAS and ATHENA achieved favorable immediate and 1-year behavioral outcomes, and they are listed on the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/). In addition, the program effects appeared durable as at 1 to 3 years following high school graduation, ATHENA intervention participants reported significantly less tobacco use, marijuana and alcohol use, plus improved nutrition and body image, compared to control group graduates [7].

In response to the National Institutes of Health’s request for new models of behavior change, the team-centered, peer-led format was applied to an occupation with natural teams, firefighting. Fire stations generally are staffed by three shifts, each working 24-h, followed by 48-h off duty. Each four to eight member shift is a team of coworkers. For the Promoting Healthy Living: Alternative Models’ Effects (PHLAME) study, fire stations within fire departments were randomized to (1) a team program, (2) to a one-on-one motivational interviewing, or (3) to a control condition [8]. The team-centered format used the same educational principles and theoretical basis as ATLAS and ATHENA. A team of coworkers (a shift at a station) met once a week for 12, 45-min scripted peer-led sessions, with one team member using a team leader manual and others workbooks. The team lessons included content related to health promotion (e.g., nutrition, physical activity, sleep) and safety (such as lifting techniques and joint protection). The team curriculum achieved immediate (1 year) [8] and longer-term favorable behavioral changes [9, 10] and was cost effective in reducing injuries [35].

Despite differences in participant characteristics, targeted behaviors, and curricula specifics, the three programs shared similar structures and showed efficacy in randomized controlled trials. Each program’s process and outcomes were deconstructed using mediation analysis. Repeated application of the same programmatic model across groups is unique, and we hypothesized that comparing patterns of confirmed action and theoretic constructs across studies could provide a robust validation of a model for behavior change.

METHODS

Detailed program descriptions and mediation methods have been published for all three programs [5–13].

Participants

One thousand five hundred six football players from 31 high schools participated in ATLAS, and 1668 adolescent female athletes from 40 sport teams at 18 high schools participated in ATHENA. Their average age was 15.9 and 15.3, for boys and girls, respectively. Overall, 85 % were White. For the PHLAME program, 397 firefighters participated in the control and team conditions, with a mean age at enrollment of 41 years; 93 % were male and 91% were White.

Design

For ATLAS, high schools were randomized to conditions after matching on win/loss records and socioeconomic status. Girls sport teams have fewer athletes than football teams, and with ATHENA, schools were paired based on size and student demographics. One school per pair was randomly assigned to the experimental condition and the other to control. An offer to participate in ATHENA was extended to all girls’ sports teams at experimental schools. After a team agreed to participate, the same sport team at the paired control school was recruited for participation. For PHLAME, 5 fire departments in the Pacific Northwest participated, and stations within departments underwent balanced randomization to the team-centered intervention (15 stations) and control (17 stations) condition. Students and their parents or guardians and firefighters provided written informed consent. The Institutional Review Board of the Oregon Health and Science University approved each study.

Measures

Firefighters were assessed by self-report questionnaires, dietary instruments, and physiological testing before beginning the program and 1-year later. For football players, pre-season and immediate post-season surveys were used. For female athletes, because sports from all three seasons were represented, the longer-term assessment varied from 9 to 12 months. For each program, specifics of the assessment constructs and their reliabilities are available in the original publications [5, 6, 8, 11–13].

Analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted for each of the individual studies [31]. Analyses controlled for any initial differences between conditions by including those measures as predictors of corresponding follow-up measures. Separate single mediator models and multiple mediator models were assessed with versions of Mplus [36], controlling for hierarchical clustering [37]. Full-information maximum likelihood was employed to include all available data. Analyses controlled for pretest differences between conditions by including pretest measures as predictors of corresponding posttest measures. The significance of mediated effects was further assessed with the PRODCLIN program [38]. For clarity and consistency, multiple mediator model findings are presented here. We combined the studies using a pattern matching approach [39], which is a process of examining a theory within different contexts and with different participant groups to validate the underlying hypotheses.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes selected mediation findings of the ATLAS, ATHENA, and PHLAME studies, and those results are overlaid on the action and conceptual model in Figure 3. Paths that are statistically significant are bold, with the width increasing depending on whether paths were significant in one, two, or three studies.

Table 1.

Mediation findings of the ATLAS, ATHENA, and PHLAME studies

| Study | Hypothesized mediator | a Path (path estimate [standard error]) | b Path (path estimate [standard error]) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATLAS | Knowledge anabolic steroid (AS) effects | 2.34 (0.23)*** | −0.02 (0.01)*** | Intentions to use AS |

| Reasons for using AS | 0.54 (0.23)*** | −0.02 (0.01)** | Intentions to use AS | |

| Perceived susceptibility to AS effects | 0.44 (0.11)*** | −0.05 (.01)*** | Intentions to use AS | |

| Team as information source | 0.56 (0.06)*** | −0.03 (.03) | Intentions to use AS | |

| Peer tolerance to drug use | −0.17 (0.10)* | 0.03 (0.02)* | Intentions to use AS | |

| Ability turn down drug offer | 0.28 (0.07)*** | −0.17 (0.02)*** | Intentions to use AS | |

| Multiple mediator model χ2 (36) = 59.817**, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.021 | ||||

| ATHENA | Knowledge diet pills, diuretics, vomiting | 0.27 (0.07)*** | 0.07 (0.02)** | Outcome expectancy for harmful effects |

| Norms society and coach concerning weight | −0.22 (0.06)*** | 0.23 (0.03)*** | Intentions to use drugs or vomiting to lose weight | |

| Mood management | 0.20 (0.07)** | −0.05 (0.02)** | Intentions to use drugs or vomiting to lose weight | |

| Self-efficacy | 0.34 (0.02)** | −0.08 (0.02)*** | Intentions to use drugs or vomiting to lose weight | |

| Multiple mediator model χ2 (209) = 706.474***, CFI = 0.911, RMSEA = 0.038, SRMR = 0.062 | ||||

| PHLAME | Knowledge benefits fruits and vegetables | 0.31 (0.08)*** | 0.65 (0.13)*** | Fruit consumption |

| Knowledge exercise benefits | 0.06 (0.09) | 0.10 (0.05)* | Self-reported physical activity | |

| Self-monitoring food intake | 0.22 (0.14) | 0.12 (06)* | Fruit consumption | |

| Coworker dietary norms | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.46 (0.12)*** | Vegetable consumption | |

| Exercise coworker support | −14 (0.09) | 0.14 (0.05)** | Self-reported physical activity | |

| Multiple mediator model χ2 (82) = 136.914***, CFI = 0.950, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.048 | ||||

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Fig 3.

Validated action and conceptual model. Solid lines are confirmed paths, with the width relating to the number of studies confirming the path. The associated numbers indicate the studies in which path was confirmed. Path coefficients (standard errors) and significance levels are shown in Table 1

The ATLAS program achieved a reduction in new anabolic steroid (AS) use, and the primary outcome was intentions to use performance-enhancing AS. Significant mediators were perceived severity and susceptibility for AS effects, knowledge of AS effects, ability to turn down drug offers, reasons for using and not using AS, perceived coach tolerance of AS use, team as an information source, and beliefs in the media. The ATHENA intervention had intentions toward harmful body-shaping actions as an outcome. For that program, changes in knowledge, norms, mood management, outcome expectancies for risky behaviors, and self-efficacy were associated with healthy changes in intentions, which in turn, were associated with behaviors. The strongest mediator of the ATHENA effects was the construct measuring perceived norms from the coach and magazine advertisements.

PHLAME’s outcomes related to both improved nutrition behaviors and regular physical activity. As shown in the figure, potential intermediate variables were in the domains of knowledge, perceived control or self-monitoring, and norms. Although the conceptual theory distal to those variables was confirmed, the intervention did not successfully change all the potential mediators, as the path from the intervention to self-monitoring was not confirmed. The mediation models fit the overall findings well for each program (Table 1) (fit is acceptable when CFI >0.95, RMSEA <0.06, SRMR <0.05 [40]).

As shown in Fig. 3, each path was significantly substantiated by at least one study, with the majority of paths significant in two or more trials. Similar findings in different populations and contexts suggest robust confirmation of the underlying process and theoretic structure.

CONCLUSIONS

Evolving more effective behavior change interventions is dependent on discerning their underlying mechanisms. Yet, few studies relate intervention outcomes back to their theoretical and process structure [2–4]. We compared the pattern of mediation findings across prospective intervention trials with different populations and behavioral outcomes to validate conceptual and action theory components and demonstrate a methodology to respond to the challenge of identifying effective processes of behavior change.

We combined the studies using a pattern matching approach [39], which is a process of replicating research with different participant groups. A more elaborate meta-analytical approach was not used in this research because only three studies were involved, and the studies differed in many respects, such as sample characteristics, construct measures, and outcomes [31, 41, 42]. As a result, we focus on the pattern of results across studies rather than combining the studies quantitatively.

Unexpectedly, knowledge emerged as a consistent mediator of behavior change. For each study, increasing understanding (e.g., risks of using anabolic steroids, knowledge about risks of diet pills, and reasons for eating fruits and vegetables) was a mediator of positive behavioral outcomes. This differs from the common wisdom that knowledge-based programs do not impact actions [43–45]. For some programs where baseline knowledge is high, such as consequences of tobacco and alcohol use, there may be little room for improvement [46]. However, as seen in marketing, certain information can have the ability to persuade [47]. In a meta-analysis of intervention studies with family caregivers, those that combined content education with social support and other tactics produced the largest effects [48]. And as mentioned in the discussion of the programs’ theoretical structure, knowledge may inform attitudes and could serve as a prerequisite for change. For example, knowing what constitutes a serving size might facilitate eating five servings of fruits and vegetables a day. Because we measured mediators and outcomes at only one time point after the intervention, we cannot differentiate whether knowledge was a prerequisite or itself instrumental. However, its importance was striking, especially considering that it generally is considered to have little impact.

A measure of team cohesion does not appear in the model, partly because the appropriate index is challenging. Cohesion needs to be related to specific tasks [49] and may vary as teams work through weekly goals toward a final objective. A recent study looking at four dimensions of cohesion found it had no impact on behavioral outcomes [50], and as those researchers pointed out, current measures for team characteristics relating to behavior change lack reliable indices of competition and cooperation.

Our findings across three evidence-based interventions with a common design but varied populations and curriculum, generally validated their theoretical underpinnings and program components’ ability to impact mediating variables. The combined results demonstrate a process for substantiating design features and theoretical models to advance the science of behavior change.

Acknowledgements

ATLAS research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA07356. The ATHENA project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse DA11748. PHLAME was supported by the National Institute on Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases AR45901 and National Cancer Institute CA105774. Dr. Moe was supported by AHRQ K12 HS019456 01. The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of these studies, nor in the interpretation and reporting of findings. All authors had full access to all of the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Compliance with ethical standards

ᅟ

Conflict of interest

ATLAS and ATHENA are made available for distribution through the Center for Health Promotion Research at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). Drs. Elliot and Goldberg have a financial interest in the sale of these products. Since completion of the original research, PHLAME is being enhanced and commercialized through an STTR grant (TR000357). Dr. Goldberg and Dr. Kuehl have a financial interest from the commercial sale of that product. These potential conflicts of interest have been reviewed and managed by the OHSU Conflict of Interest in Research Committee at OHSU. Drs. MacKinnon, Ranby and Moe have no conflict of interest.

Adherence to ethical standards

All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: A team-centered intervention using peer-led curricula and individual and team level behavioral monitoring appears to be an effective model for health promotion.

Policy: Replication of programs and translation in new settings can be informed by selecting those with confirmed theoretical and process structures.

Research: Combining the patterns of mediation findings across studies can be used to assist filling the knowledge gap concerning defining effective processes of behavior change.

Contributor Information

Diane L Elliot, Phone: (503) 494-6554, Email: elliotd@ohsu.edu.

Linn Goldberg, Email: goldberl@ohsu.edu.

David P MacKinnon, Email: david.mackinnon@asu.edu.

Krista W Ranby, Email: krista.ranby@UCDenver.edu.

Kerry S Kuehl, Email: kuehlk@ohsu.edu.

Esther L Moe, Email: moe@ohsu.edu.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Health and behavior: the interplay of biological, behavioral, and societal influences; Committee on Health and Behavior: Research, Practice and Policy Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avery KNL, Donovon JL, Horwood J, et al. Behavior theory for dietary interventions for cancer prevention: a systematic review of utilization and effectiveness in creating behavior change. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:409–420. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9995-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. 2010;5:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor N, Conner M, Lawton R. The impact of theory on the effectiveness of worksite physical activity interventions: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Health Psychol Res. 2012;6:33–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg L, MacKinnon DP, Elliot DL, et al. The adolescents training and learning to avoid steroids program: preventing drug use and promoting healthy behaviors. Arch Pediat Adolesc Med. 2000;154:332–338. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Moe EL, et al. Preventing substance use and disordered eating: initial outcomes of the ATHENA (athletes targeting healthy exercise and nutrition alternatives) program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:1043–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.11.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Moe EL, et al. Long-term outcomes of the ATHENA (Athletes Targeting Healthy Exercise & Nutrition Alternatives) program for female high school athletes. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2008;52:73–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Kuehl KS, et al. The PHLAME study: process and outcomes of two models of behavior change. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49:204–213. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3180329a8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKinnon DP, Elliot DL, Thoemmes F, et al. Long-term effects of a worksite health promotion program for firefighters. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:695–706. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.34.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mabry L, Elliot DL, MacKinnon DP, et al. Understanding the durability of a fire department wellness program. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37:693–702. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.5.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacKinnon DP, Goldberg L, Clarke GN, et al. Mediating mechanisms in a program to reduce intentions to use anabolic steroids and improve exercise self-efficacy and dietary behavior. Prevention Sci. 2001;2:15–28. doi: 10.1023/A:1010082828000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranby KW, Aiken LS, MacKinnon DP, et al. A mediation analysis of the ATHENA intervention: reducing athletic-enhancing substance use and unhealthy weight loss behaviors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:1069–1083. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranby KW, MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, et al. The PHLAME (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models’ Effects) firefighter study: testing Mediating mechanisms. J Occup Health Psychol. 2011;16:501–513. doi: 10.1037/a0023002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:354–386. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Human DeciProc. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. The evolution of social cognitive theory. In: Smith KG, Hitt MA, editors. Great minds in management. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H-T. Theory-driven evaluations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behav Human Disease Proc. 1991;50:248–287. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankham J. Peer education: unauthorized version. Brit Educ Research J. 1998;24:179–193. doi: 10.1080/0141192980240205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen VL, Wilder DA. Social comparison, self evaluation, and conformity to the group. In: Suls JM, Miller RL, editors. Social comparison processes: theoretical and empirical perspectives. New York, NY: Hemisphere; 1977. pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webel AR, Okonsky J, Trompeta J, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:247–253. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelmann S, Carnine DW. Theory of instruction: principles and applications. New York, NY: Irvington; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollingsworth J, Ybarra S. Explicit direct instruction: the power of the well-crafted and well taught lesion. DataWORKS Educational Research: Fowler, CA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner (seventh edition) Oxford, England: Elsevier, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watkins CL. Project follow through: a story of the identification and neglect of effective instruction. Youth Policy. 1988;10(7):7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, et al. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701. doi: 10.1037/a0016136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katzenbach JR, Smith DK. The discipline of teams. Harv Bus Rev. 1993;71:162–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guzzo RA, Dickson MW. Teams in organizations: research on performance effectiveness. Annu Rev Psychol. 1996;47:307–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen G, Kaufer R. Toward a systems theory of motivated behavior in work teams. Res Organizational Behav. 2006;27:223–267. doi: 10.1016/S0191-3085(06)27006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siemsen E, Balasubramanian S, Roth A. Incentives induce task-related effort, helping, and knowledge sharing in work-groups. Manag Sci. 2007;53:1533–1550. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1070.0714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. pp. 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ. Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions Psychol Sci. 2009;18:16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockwood CM, DeFrancesco CA, Elliot DL, et al. Mediation analyses: applications in nutrition research and reading the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, et al. An ecological approach to creating more physically active communities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuehl KS, Elliot DL, Goldberg L, et al. Economic benefit of the PHLAME wellness programme on firefighter injury. Occup Med. 2013;63:203–209. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqs232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthe ´NB, Muthe ´NL. Mplus 5 User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthe´n & Muthe´n; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods (2nd edition) Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, et al. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect program PRODCLIN. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/BF03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trochim WMK. Pattern matching, validity, and conceptualization in program evaluation. Eval Rev. 1985;9:575–604. doi: 10.1177/0193841X8500900503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analyses: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook TD, Cooper H, Cordray DS, et al. Meta-analysis for explanation: a casebook. New York, NY: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker BJ. Model-based meta-analysis. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 2009. pp. 377–395. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Contento I, Balch GI, Bronner YL, et al. The effectiveness of nutrition education and implications for nutrition education policy, programs, and research: a review of research. J Nutr Educ. 1995;27:277–418. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management and education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothman A, Kiuiniemi M. Treating people with information: an M. Treating people with information: an analysis and review of approaches to community risk information. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999;25:44–57. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacKinnon DP, Johnson CA, Pentz MA, et al. Mediating mechanisms in a school-based drug prevention program: first-year effects of the Midwestern Prevention Project. Health Psychol. 1991;10:164–172. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.10.3.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shrum LT, Liu M, Nespoli M, et al. Persuasion in the market place. In: Dillard JP, Shen L, et al., editors. The persuasion handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. pp. 314–330. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42:356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Estabrooks PA. Sustaining exercise participation through group cohesion. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith-Ray RL, Mama S, Reese-Smith JY, et al. Improving participation rates for women of color in health research: the role of group cohesion. Prev Sci. 2012;13:27–35. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0241-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]