Knowledge of the atomic resolution structures of viruses can be a powerful tool for vaccine discovery and design. X-ray crystallography has long served as an invaluable method for virus structure determination at high resolution, but over the past decade, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has begun to emerge as a complementary method that can also provide this kind of information. Crystallographic approaches require significant amounts of purified virus that is structurally homogeneous. In instances where production of adequate amounts of purified virus can be challenging, or where homogeneity is difficult to achieve, the use of cryo-EM and image averaging may be the only way to obtain structural information at high resolution. In PNAS, Rossmann and co-workers (1) use cryo-EM techniques to present elegant results on the structure determination of rhinovirus C, a strain of rhinovirus that is associated with severe disease in children with asthma (2). Rhinoviruses of A, B, and C categories are the leading cause of common colds; there are well over 100 of these types of viruses. Efforts to understand the molecular mechanism of cell receptor binding and differences between rhinovirus strains have been hampered by the lack of structural information, especially for those strains that are difficult to propagate in cell culture (3).

It was almost two decades ago that the first breakthroughs were made in the use of cryo-EM for virus structure determination, with the report of structures at ∼7 Å resolution of the hepatitis B capsid (4, 5). A decade later, the first near-atomic resolution maps of icosahedral viruses, derived solely from cryo-EM, were published (6, 7). Since that time, as methods for high-resolution cryo-EM have become more widely used, dozens of near-atomic resolution structures of icosahedral viruses have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb). In addition to the present study (1), the same group reported earlier this year (8) the near-atomic resolution structure of Zika virus, a pathogen that has recently been emerging as a major public health threat (9). Icosahedral viruses, including the picornavirus and flavivirus families (to which rhinovirus and Zika virus belong, respectively), are uniquely suited to rapid structure determination by cryo-EM, as explained below.

Three-dimensional structure determination by cryo-EM involves averaging the information present in 2D projection images of multiple copies of individual particles, which are oriented variably with respect to the incident electron beam. In the case of icosahedral viruses, although each individual virion can be considered a particle, the symmetry of these structures is such that many identical copies of the asymmetrical unit are included in each particle, increasing by many fold the effective number of units averaged to determine the structure. The intermolecular interactions between the asymmetrical units of the icosahedral capsid provide a level of order that increases the accuracy of alignment, a feature also relevant for viruses with helical capsids (10, 11). In contrast, the outer membranes of enveloped viruses, such as influenza, Ebola, and HIV, display their envelope proteins in a highly disordered arrangement, and structure determination of envelope glycoproteins requires the use of subvolume averaging methods, which have only produced low-resolution structures so far (12, 13).

The study by Liu et al. (1) on rhinovirus C offers a particularly intriguing look at the potential future of structure determination for vaccine design for emerging pathogens. Even after overcoming the initial hurdle of virus propagation in tissue culture, the team still had to work with a relatively low concentration of the virus purified only through sucrose cushion sedimentation. This relatively quick preparation yielded preparations with a modest number of virus particles as well as a mixture of both normal infectious virions and empty particles (which contained only the capsid shell without viral RNA). From this mixed sample, the authors were able to sort the full and empty particles computationally and to determine the structures of both to near-atomic resolution. A notable technical aspect of the work is that the authors compensated for the lower concentration by working with lower electron optical magnifications than are typically used, so that more virions were present in a given field of view. The use of lower magnifications can introduce significant image distortions, but the authors were successful in compensating for these defects. Not only is their 2.8 Å resolution structure of the full virus (with ∼9,000 particles) one of the highest resolution cryo-EM icosahedral virus structures to have been reported but their 3.2 Å resolution structure of the empty virus (with ∼3,600 particles) also used the fewest particles for any icosahedral virus reconstruction yet reported at near-atomic resolution.

Viruses in the picornavirus family, which includes both enteroviruses and rhinoviruses, have a capsid protein shell that is not covered by an outer envelope layer. The capsid proteins of these icosahedral viruses are thus responsible for interacting with target cell receptors. In their structural study of rhinovirus C, Liu et al. (1) examine the shape of the canyon (14), a pocket at the base of the protruding spikes on the surface of the rhinovirus capsid. A similar location on the enterovirus D68, a related virus also associated with severe disease in children, had previously been shown to interact with sialylated cadherin-related family member 3 (CDHR3) (15). Whereas other rhinoviruses have flat plateaus and wide canyons in their capsid surface, the rhinovirus C surface canyons more closely resemble the surface canyons of enterovirus D68; a closer look at the canyons (Fig. 1) suggests that rhinovirus C likely also binds sialic acid on CDHR3 in much the same manner as enterovirus D68. Interestingly, although related rhinoviruses have another cavity on the surface that can be targeted by “pocket factor” inhibitors (16, 17), this structure of rhinovirus C, also like enterovirus D68, indicates that the pocket factor binding site is unavailable, explaining the resistance of these viruses to pocket factor inhibitors. Another interesting aspect of this study is the structure determination of empty particles along with the full virions from the same sample. These empty particles were found to be noninfectious, yet still displayed highly similar exterior capsid features to the full virions, indicating that these empty particles may prove useful as immunogens for vaccine design, assuming no profound differences in antigenic presentation (18).

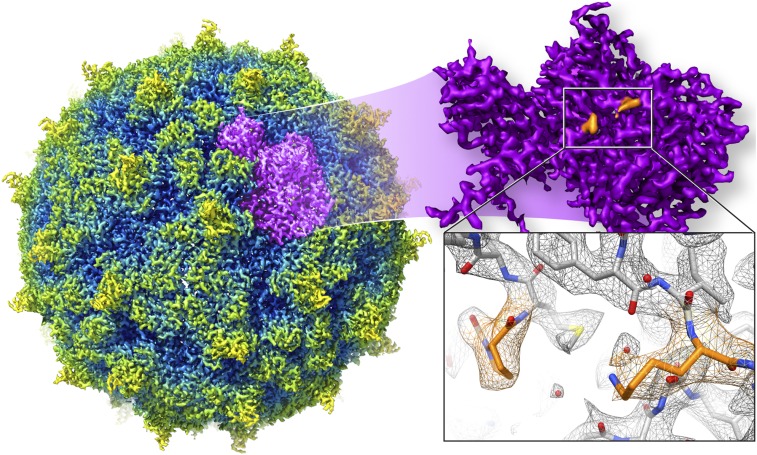

Fig. 1.

Cryo-EM structure of rhinovirus C 15a, displaying icosahedral symmetry, with spikes (yellow) and valleys in the surface. Each asymmetrical unit (purple) includes a canyon next to the spike; in this canyon, proline and lysine residues (orange) form a pocket likely to interact with sialic acid.

The use of cryo-EM methods to visualize multiple high-resolution maps from a single, simply purified, low-concentration sample represents a significant advance toward being able to use cryo-EM to analyze structural information of new and emerging viruses rapidly. A number of such viruses, either newly discovered or just now emerging as public health threats, have been identified over the past few years alone, including the Ebola virus and Zika virus, as well as enterovirus D68, rhinovirus C, and others. The structural composition of the virus, and particularly the structure of the virus coat (whether it has an ordered, icosahedral or helical coat, or whether the virus is covered with envelope membrane and dotted with envelope proteins displayed in a disordered manner), can be extremely important in ascertaining whether it is possible to determine a structure of the virus quickly, or even whether such a structure will have bearing on the development of a vaccine or a therapeutic. Thus, members of both the nonenveloped icosahedral picornavirus family (such as enteroviruses and rhinoviruses), and enveloped icosahedral families, such as flaviviruses (e.g., dengue virus, Zika virus), have yielded to high-resolution structure determination by cryo-EM. Enveloped viruses, such as the influenza viruses, HIV, and Ebola virus, where there is no icosahedral ordering of the surface components, have proven much more challenging (19), although progress toward in situ high-resolution structural analysis of the ordered regions of these viral assemblies is being made (20).

There are several important elements for applying structural information to vaccine design for newly emerging pathogens: It is critical that structural information be obtained quickly, from native samples, and at sufficiently high resolution to shed light on immunogenic surfaces of the virus. With this study, Liu et al. (1) have shown that cryo-EM can be used to determine a structure quickly, even when the biochemistry involved in virus preparation can be challenging. Although these methods may not be generally applicable to every emerging pathogen, cryo-EM is likely to increasingly become a routine tool to aid rapid vaccine design, especially for icoshedrally symmetric viruses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Veronica Falconieri for assistance with production of the figure. The authors' research is supported by funds from the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 8997.

References

- 1.Liu Y, et al. Atomic structure of a rhinovirus C, a virus species linked to severe childhood asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:8997–9002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606595113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bizzintino J, et al. Association between human rhinovirus C and severity of acute asthma in children. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(5):1037–1042. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bochkov YA, et al. Molecular modeling, organ culture and reverse genetics for a newly identified human rhinovirus C. Nat Med. 2011;17(5):627–632. doi: 10.1038/nm.2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Böttcher B, Wynne SA, Crowther RA. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 1997;386(6620):88–91. doi: 10.1038/386088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway JF, et al. Visualization of a 4-helix bundle in the hepatitis B virus capsid by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature. 1997;386(6620):91–94. doi: 10.1038/386091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu X, Jin L, Zhou ZH. 3.88 A structure of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature. 2008;453(7193):415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature06893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, et al. Near-atomic resolution using electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle reconstruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(6):1867–1872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711623105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirohi D, et al. The 3.8 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus. Science. 2016;352(6284):467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauci AS, Morens DM. Zika virus in the Americas--yet another arbovirus threat. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):601–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiMaio F, et al. Virology. A virus that infects a hyperthermophile encapsidates A-form DNA. Science. 2015;348(6237):914–917. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMaio F, et al. The molecular basis for flexibility in the flexible filamentous plant viruses. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(8):642–644. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008;455(7209):109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huiskonen JT, et al. Averaging of viral envelope glycoprotein spikes from electron cryotomography reconstructions using Jsubtomo. J Vis Exp. 2014;(92):e51714. doi: 10.3791/51714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith TJ, Chase ES, Schmidt TJ, Olson NH, Baker TS. Neutralizing antibody to human rhinovirus 14 penetrates the receptor-binding canyon. Nature. 1996;383(6598):350–354. doi: 10.1038/383350a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, et al. Sialic acid-dependent cell entry of human enterovirus D68. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8865. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, et al. Structure and inhibition of EV-D68, a virus that causes respiratory illness in children. Science. 2015;347(6217):71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1261962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Colibus L, et al. More-powerful virus inhibitors from structure-based analysis of HEV71 capsid-binding molecules. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(3):282–288. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotecha A, et al. Structure-based energetics of protein interfaces guides foot-and-mouth disease virus vaccine design. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(10):788–794. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran EE, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of chimeric hemagglutinin displayed on a universal influenza vaccine candidate. MBio. 2016;7(2):e00257. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00257-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schur FK, et al. An atomic model of HIV-1 capsid-SP1 reveals structures regulating assembly and maturation. Science. July 14, 2016 doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]