Abstract

High-throughput genome sequencing continues to grow the need for rapid, accurate genome annotation and tRNA genes constitute the largest family of essential, ever-present non-coding RNA genes. Newly developed tRNAscan-SE 2.0 has advanced the state-of-the-art methodology in tRNA gene detection and functional prediction, captured by rich new content of the companion Genomic tRNA Database. Previously, web-server tRNA detection was isolated from knowledge of existing tRNAs and their annotation. In this update of the tRNAscan-SE On-line resource, we tie together improvements in tRNA classification with greatly enhanced biological context via dynamically generated links between web server search results, the most relevant genes in the GtRNAdb and interactive, rich genome context provided by UCSC genome browsers. The tRNAscan-SE On-line web server can be accessed at http://trna.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/.

INTRODUCTION

Transfer RNAs, a central component of protein translation, represent a highly complex class of genes that are ancient yet still evolving. tRNAscan-SE remains the de facto tool for identifying tRNA genes encoded in genomes with over 5000 citations (1), and has a wide variety of users including sequencing centers, biological database annotators, RNA biologists and computational biology researchers. Transfer RNAs predicted using tRNAscan-SE are currently available for thousands of genomes in the GtRNAdb (2,3), yet the GtRNAdb is not designed for user-driven tRNA gene detection. We previously described the tRNAscan-SE web server 11 years ago (4), a publication that has garnered over 750 citations (Google Scholar) and has been downloaded for full-text viewing more than 7500 times (Nucleic Acids Research Article Metrics). The original tRNAscan-SE web server currently receives about 1000 unique visitors a month, aiding a large swath of the research community that may not have computational resources or expertise to install and run the UNIX-based software.

Here, we describe a new web analysis server in conjunction with the development of tRNAscan-SE 2.0 (Chan et al., in preparation). The new version of tRNAscan-SE has improved covariance model search technology enabled by the Infernal 1.1 software (5); updated covariance models for more sensitive tRNA searches, leveraging a much broader diversity of tRNA genes from thousands of sequenced genomes; better functional classification of tRNAs, based on comparative analysis using a suite of 22 isotype-specific tRNA covariance models for each domain of life; and ability to detect mitochondrial tRNAs (in addition to cytosolic eukaryotic, archaeal and bacterial tRNAs), with high accuracy using new mitochondrial-specific models. In addition to new search capabilities, the web server now enables users to place their tRNA predictions in similarity context within the GtRNAdb, as well as genomic context within available UCSC genome browsers.

TRNA GENE SEARCH

Similar to the original version of the tRNAscan-SE search server (4), users may select among multiple types of tRNAs (mixed/general, eukaryotic, bacterial, archaeal or mitochondrial) as well as different search modes to identify tRNA genes in their provided sequences. The default search mode of tRNAscan-SE 2.0 (Chan et al., in preparation) utilizes the latest version of the Infernal software package (v1.1.1) (5) to search DNA sequences for tRNA-like structure and sequence similarities. The Infernal software implements a special case of profile stochastic context-free grammars called covariance models, which can be trained to have different specificities depending on the selection of structurally aligned RNA sequences which serve as training sets. tRNAscan-SE 2.0 employs a suite of covariance models in multiple analysis steps to maximize sensitivity and classification accuracy.

In an initial first-pass scan, Infernal is used with a relatively permissive score threshold (10 bits) in combination with a search model trained on tRNAs from all tRNA isotypes in order to obtain high sensitivity. The mid-level strictness filter (‘- -mid’) is also used to accelerate search speed at minimal cost to sensitivity. The user can choose to search with a tRNA model trained on tRNAs from all domains of life (‘Mixed’), or preferably, select from one of three domain-specific models trained on tRNAs exclusively from Archaea, Bacteria or Eukarya. A second-pass scan of individual candidates detected in the first-pass also uses Infernal (5) but with a higher score threshold to increase selectivity, no acceleration filter to increase alignment accuracy and multiple isotype-specific covariance models to better determine isotype identity. These changes in the tRNAscan-SE 2.0 software and search models produce slightly different bit scores relative to tRNAscan-SE 1.2.1 (1), although the relative rankings of previously detected tRNAs should largely be unchanged. In order to provide backward comparisons when needed, researchers can select a ‘legacy’ search mode which uses the tRNAscan-SE 1.2.1 search software. For users who need maximum search sensitivity for low-scoring tRNA-like sequences (e.g. tRNA-derived SINEs or pseudogenes), we include the search mode option ‘Infernal without HMM’ which is only recommended for very short sequence queries due to the slow search speed.

FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATION USING ISOTYPE-SPECIFIC COVARIANCE MODELS

Sequence and structure-based determinants, both positive and negative, are used by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases to establish tRNA identity, and have been characterized in a number of model species (6). Previously, we used the anticodon exclusively to predict tRNA isotype because the anticodon can be easily identified within a tRNA gene candidate and nearly always gives unambiguous identification of the tRNA isotype. However, there exist cases of ‘chimeric’ tRNAs in which point mutation(s) in the anticodon sequence could result in ‘recoding’ events (7,8). In this case, the body of the tRNA contains identity elements recognized by one type of tRNA synthetase, yet the altered anticodon ‘reads’ the mRNA codon corresponding to a different amino acid. The decoding behavior of such tRNAs could theoretically be modulated by post-transcriptional anticodon modifications that either preserve or alter the genetic code. The full biological scope and significance of chimeric tRNAs is not well understood because of the historical lack of large-scale, systematic detection methods, but it is now possible and valuable to detect these potentially important chimeric tRNAs which could result in tissue or condition-specific recoding of proteins.

Thus, we developed a new multi-model annotation strategy for tRNAscan-SE 2.0 where, after establishing tRNA gene coordinates and predicting function by anticodon, we also analyze the gene prediction with a full set of isotype-specific covariance models, in a strategy similar to TFAM (9). These 20+ models are built by simply sub-dividing the original tRNA training set into subgroups of the universal 20 amino acids (Ala, Arg, Cys, etc), plus one for initiator/formyl-methionine (iMet/fMet), one to identify prokaryotic Ile tRNAs genomically encoded with a CAT anticodon, and one to recognize selenocysteine tRNAs. Each of these subgroups forms the basis for 20+ models for each domain (22 for eukaryotes, 23 for bacteria, 23 for archaea). Now, alongside the predicted isotype based on the anticodon, the highest scoring isotype-specific model is also reported; any disagreement between the two functional prediction methods is reported for closer user inspection. There may be insufficient data to establish the true tRNA identity when there is disagreement because tRNA synthetase identity elements have only been experimentally verified in a small number of species. However, we believe this supplemental isotype-specific model analysis will enable the tRNA research community to more readily identify and experimentally investigate potential tRNA chimeras in the future. An example of this type of potential chimeric tRNA is human Val-AAC-6-1 (‘GGGGGTGTAGCTCAGTGGTAGAGCGTATGCTTAACATTCATGAGGCTCTGGGTTCGATCCCCAGCACTTCCA’) that contains the anticodon AAC (in bold), but scores highest against the eukaryotic tRNA isotype model for alanine.

EXPLORING TRNA CONTEXT: GTRNADB AND LOCUS CONTEXT

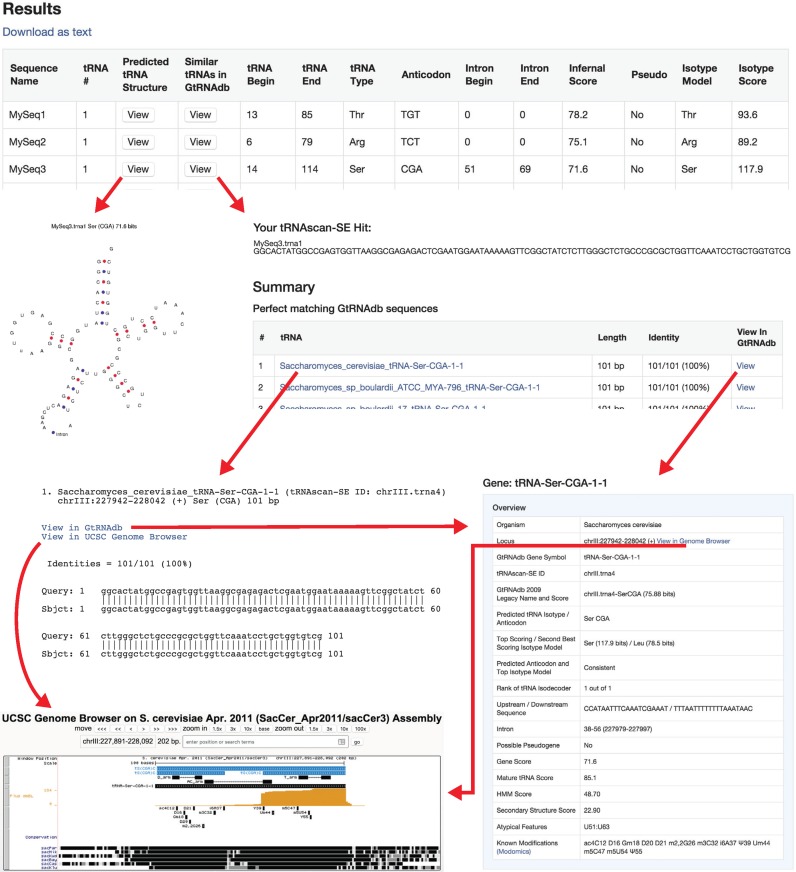

The resulting tRNAs identified in the user's sequence can be searched against the GtRNAdb (3), yielding links to identical or highly similar tRNA genes found in the database (Figure 1). If a UCSC Genome Browser (10,11) exists for any identical or close tRNA matches, a direct link is provided to those matches, enabling the user to examine its genomic context and any additional information available in genome browser tracks. In the example given (Figure 1), ‘MySeq3’ contains one tRNA prediction yielding an Infernal score of 71.6 bits, as scored by an ‘all-isotype’ eukaryotic tRNA model. The identified tRNA has one intron and is predicted to be charged with serine based on the CGA anticodon inferred from the predicted tRNA secondary structure. Upon comparison to the full suite of specialized/isotype-specific models, the highest scoring model in second-pass analysis corresponded to tRNA-Serine, at 117.9 bits. tRNAs will usually get a higher score against their true isotype-specific model because specialized models are not ‘diluted’ by tRNA sequence features found only in other isotypes. Selecting the first button in each row visualizes the predicted secondary structure, while the second button executes a fast sequence similarity search to find identical or very similar tRNAs in the GtRNAdb. The figure shows perfect matches to Ser-CGA tRNAs in several Saccharomyces species; upon selecting the ‘View’ link for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ser-CGA-1-1, its individual gene page displays a wealth of information, including upstream and downstream genomic sequences, atypical features (U51:U63), 13 RNA modifications previously characterized, a multiple sequence alignment with all other Ser tRNA genes in this species (not shown) and tRNA-seq expression profiles for mature and pre-tRNAs mapped to this locus (not shown). Finally, links from either the GtRNAdb gene page, or the list of perfect matching hits shows the tRNA gene in the interactive UCSC Genome Browser with tracks that show the level of multi-genome conservation among six other yeast species, the positions of previously noted modifications, tRNA-seq expression data and the ‘SGD Genes’ track, aiding further exploration of this gene's biological context.

Figure 1.

Example tRNAscan-SE Search and Contextual Analysis. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA-SerCGA is analyzed using the tRNAscan-SE web server in default eukaryotic search mode. The red arrows show the analysis path from viewing the predicted tRNA results to finding the matching tRNA gene in GtRNAdb (3), to exploring the tRNA gene in context with tRNA modifications and gene expression data in the UCSC Genome Browser (10).

FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

As the technology for sequencing and assembling genomes continues to improve, we anticipate that the demand to identify and annotate tRNA genes in new, complete genomes will continue to accelerate. Accordingly, we plan to produce a tRNA gene set ‘completeness’ report using phylogenetic patterns of tRNA set composition observed across all genomes represented in the GtRNAdb. Noting potential ‘missing’ or ‘surplus’ tRNA gene decoding potential will be useful to assess genome quality and completeness, as well as recognizing potential genome assembly errors or sequencing contamination. A second planned capability is metagenomic analysis of sequencing data containing an unknown mix of species. By doing comparative analysis using a suite of isotype-specific and phylum-specific covariance models (under development now), we hope to offer a tRNA identification and phylogenetic classification service as part of the tRNAscan-SE web server. Finally, with the increase in knowledge of functional tRNA fragments, we plan to offer detection and systematic classification of fragments in the context of full-length tRNA genes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lowe Lab members Brian Lin, Allysia Mak and Aaron Cozen for their work in development of the new covariance models for tRNAscan-SE 2.0, as well as their assistance in extensive testing and feedback on the web server interface.

FUNDING

National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health [HG006753-02 to T.L.]. Funding for open access charge: NHGRI/NIH [HG006753-02]; University of California, Santa Cruz department chair research stipend.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan P.P., Lowe T.M. GtRNAdb: a database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D93–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan P.P., Lowe T.M. GtRNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D184–D189. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schattner P., Brooks A.N., Lowe T.M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W686–W689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nawrocki E.P., Eddy S.R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2933–2935. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giege R., Sissler M., Florentz C. Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5017–5035. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry J., Dai X., Zhao Y. A mutation in the anticodon of a single tRNAala is sufficient to confer auxin resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1284–1290. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.068700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimata Y., Yanagida M. Suppression of a mitotic mutant by tRNA-Ala anticodon mutations that produce a dominant defect in late mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2283–2293. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ardell D.H., Andersson S.G. TFAM detects co-evolution of tRNA identity rules with lateral transfer of histidyl-tRNA synthetase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:893–904. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Speir M.L., Zweig A.S., Rosenbloom K.R., Raney B.J., Paten B., Nejad P., Lee B.T., Learned K., Karolchik D., Hinrichs A.S., et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D717–D725. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan P.P., Holmes A.D., Smith A.M., Tran D., Lowe T.M. The UCSC Archaeal Genome Browser: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D646–D652. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]