Abstract

The objective of this study was to translate and adapt five English self-report health measures to a South Indian language Kannada. Currently, no systematically developed questionnaires assessing hearing rehabilitation outcomes are available for clinical or research use in Kannada. The questionnaires included for translation and adaptation were the hearing handicap questionnaire, the international outcome inventory - hearing aids, the self-assessment of communication, the participation scale, and the assessment of quality of life – 4 dimensions. The questionnaires were translated and adapted using the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) guidelines. The five stages followed in the study included: i) forward translation; ii) common translation synthesis; iii) backward translation; iv) expert committee review; v) pre-final testing. In this paper, in addition to a description of the process, we also highlight practical issues faced while adopting the procedure with an aim to help readers better understand the intricacies involved in such processes. This can be helpful to researchers and clinicians who are keen to adapt standard self-report questionnaires from other languages to their native language.

Key words: Translation, adaptation, hearing loss, hearing aids, self-report measures

Introduction

Benefit from hearing aids can be measured in multiple ways. Common methods are lab-based tests and use of outcome questionnaires. Lab-based outcome tests such as speech perception tests conducted in a sound booth, although help to gauge the benefit of using a hearing aid compared to unaided conditions, they do not always simulate real-world listening situations.1 Limitation in generalization is therefore a shortcoming of using solely these tests to measure hearing aid benefit. In support of this, evidence-based practice demands audiologists to demonstrate real world benefits from hearing aids.2 This necessitated the development and use of self-reported outcome measures. These measures are now considered as the gold standard for measuring real success with hearing aid(s).2

Self-report outcome measures are patient-centered methods3 primarily used to assess severity of the disability and to verify treatment success on an individual basis. In the context of hearing rehabilitation (e.g., hearing aid fitting), these measures aim to assess different domains, including perceived severity of hearing disability, hearing aid usage, benefit, satisfaction, participation restriction, quality of life, etc.

There are so many measures available for clinical and research use in developed countries [e.g., hearing handicap questionnaire (HHQ),4 international outcome inventory - hearing aids (IOI-HA),5 self-assessment of communication (SAC)6]. Standardized self-report health questionnaires are rarely available in developing countries like India. An additional challenge in a country like India is its linguistic diversity. Over 122 major languages have been identified in India.7 Developing new language specific questionnaires is demanding in terms of time, money and effort8 and hence, translation of questionnaires to local languages and cultures would be a more practical method. The goal of the present study was to translate and adapt five commonly used self-report English health questionnaires into a South Indian language, Kannada.

Translation of research questionnaires is a complex process and is a major step in cross-cultural research. Earlier models of translations only considered mere forward or direct translation, i.e., single step translation of the questionnaire from the original language to the target language. However, it was soon identified that this may be insufficient to obtain a successful translation and, therefore, using a backward translation was recommended as a subsequent step.9 The backward translation refers to the process of translating the questionnaire from the target language back to the original language. The reason of this step is to cross check the congruence in meaning between the original and target language. Since cultural practices vary, the task of translation is not limited to confirming their semantic equivalence. The process also demands serious reflection on compatibility to target population, culture, location, etc.10 Therefore, many translation experts now use the term adaptation along with translation to reflect the process of introducing modifications to ensure that the measure is appropriate for the local context.

Currently, there is no universally accepted method followed in translating and adapting any health measure. However, there are many guidelines proposed for a valid translation. Few of them include the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines,11 the Medical Outcome Trust recommendations,12 the Translation, Review, Adjudication, Pretesting, and Documentation (TRAPD) team translation model,10 the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) guidelines,13 the Linguistic validation process by Mapi Research Institute,14 etc. Four commonly recommended procedural considerations in the above guidelines include: i) multiple forward translations; ii) backward translation; iii) expert committee review approach; iv) pre-final testing. These four methodological considerations are discussed below.

Multiple forward translations, the first step in the translation-adaptation process, advocates for multiple translators during forward translation.15 The minimal recommendation is to have two bilingual translators.12 Having multiple translators and thus, multiple forward translations facilitate identification of semantic differences in ambiguous terms.16 Considering translators with similar educational backgrounds is also not recommended in an attempt to avoid the use of field-specific jargon. Using a team of translators with supplementary skills like good familiarity with local culture, in-depth knowledge of the field, and expertise with the research methodology and translation process is recommended too.8

The multiple forward translation stage is followed by generation of a single combined accepted version of the forward translations. All the translators and key researchers take part in this process. A few methodological recommendations like AAOS guidelines consider this process of common version synthesis as a separate step in the translation procedure.

Backward translation,9 the second major step in the translation-adaptation process, is suggested as a means to confirm effective original-totarget language translation. It acts as a quality check and aims to highlight gross discrepancies and conceptual errors. It helps in mapping the semantic equivalence between the original and the target version of the translated measure.17 The backward translation should preferably be performed by outsourced bilingual translators,18 who are not related to the research group and are ignorant of the research concept.

The third step, expert committee review approach is to have an expert committee to compare and analyze the forward and back translations. A panel of experts in the content area, the translators, and the researchers are generally involved in the review and evaluation of the translated measures.19 Their task is to examine whether the translation is accurate and if it maps to the original intent of the items. The original author, if proficient in the target language can also be invited to participate in the expert panel or at least he can be requested to help in clarifying differences observed (if any arise) between the source and the target versions.

Pre-final testing, the final recommended stage, is also referred to as cognitive interviewing/debriefing. This phase generally involves using the pre-final version of the measure to conduct interviews with a sample of the target population and obtaining their opinion/feedback regarding acceptance and understanding of the items.19 This enables researchers to confirm whether the measures are simple, clear, understandable and contextually appropriate. Further, it helps the researchers to verify the use of proficient language and culturally inoffensive items in the translation.

The present study aimed to translate and adapt five self-report English health questionnaires into the Kannada language. This study is a part of a larger ongoing project that aims to understand the outcome of hearing aid use in community-based rehabilitation (CBR) setups in India. We chose Kannada because it is one of the Dravidian languages spoken in South India by around 38 million speakers7 and, also because the project CBR site is in Karnataka state where Kannada is the official language.

Materials and Methods

The study protocol was approved by the ethics board at the All India Institute of Speech and Hearing, University of Mysore, Mysore, Karnataka, India.

Self-report outcome measures

The five questionnaires considered in the study include: i) HHQ; ii) IOI-HA; iii) SAC; iv) participation scale (PS); v) assessment of quality of life – 4 dimensions (AQoL - 4D).

HHQ4 is an instrument to measure hearing disability as defined by WHO’s international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). This questionnaire has 12 questions and uses a 5-point scale from never to almost always as a response option. Emotional distress and uneasiness, social withdrawal and participation restrictions are the domains measured by this instrument. HHQ is reported to be having good Cronbach’s alpha (internal consistency) for both the emotional (0.95) and social scale (0.93).

IOI-HA5 aims to assess the effectiveness of hearing aid rehabilitation. It is a seven-item self-report questionnaire evaluating seven different hearing aid outcome domains, including: i) hearing aid use; ii) benefit; iii) activity limitations (residual); iv) satisfaction; v) residual participation restriction; vi) impact on others and vii) quality of life. The original version of IOI-HA is in English and was developed by Cox and colleagues.5 This questionnaire has now been translated into thirty different languages and is used worldwide.20 The psychometric properties of the English version on veteran hearing aid users indicate good internal consistency (0.83 Chronbach’s alpha) and high test-retest reliability (0.94).21

SAC6 is also one of the hearing aid outcome questionnaires developed based on WHO-ICF. In this questionnaire, the first five questions focus on disability and later four questions target participation restriction. Similar to IOI-HA, it is a brief and comprehensive measure recommended by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)22 for screening the hearing disability in adults using hearing aids. SAC was one of the top five self-report measures used by audiologists in the United States.23

PS, also known as (social) participation scale, is a measure of 18 items to assess the severity of participation restriction of individuals with different disabilities.24 It is used to assess the need for rehabilitation and the impact of interventions on reduction in participation restriction. The psychometric properties have been evaluated for various disabilities in three different countries in six languages. Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 for the full scale with an inter-rater reliability of 0.90 has been reported.25

AQoL - 4D is a measure to assess the quality of life related to health.26 It is a simple global utility score. It has 12 questions to assess four different domains, including: i) independent living (self-care, household tasks and mobility); ii) relationships (friendships, isolation and family role); iii) mental health (sleeping, worrying and pain); and iv) senses (seeing, hearing and communication).

Translation and adaptation

All the questionnaires were translated using the well-accepted AAOS guidelines which included forward-backward translation method.13 AAOS guidelines are one of the first extensive descriptions of methodology to be used for translating and adapting measures.27 This method includes five stages: i) forward translation; ii) synthesizing common translation; iii) backward translation; iv) expert committee review; v) pre-final testing.

Participants

For pre-final testing of the translation measure, 37 participants (age in years: mean=56.4; SD=+/-16.79; range=22 to 81; 26 males) were included following convenience sampling based on the following criteria: i) age above 18 years; ii) hearing loss of any degree and hearing aid use for at least 2 weeks; iii) Kannada-English bilinguals with Kannada as the native/first language. These participants were recruited from a speech and hearing institutional rehabilitation set-up and two private clinics in Mysore district of Karnataka state. All but three participants had a bilateral hearing loss. The duration of hearing loss and duration of hearing aid usage ranged between 3 months to 40 years and 18 days to 27 years, respectively. Participants either used behind the ear or receiver in the canal hearing aids.

Results

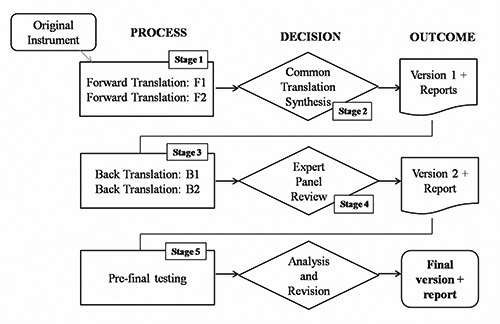

The five main stages involved in this study are discussed below. Figure 1 depicts the translation procedure followed.14

Figure 1.

Flowchart of translation-adaptation process as per the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons guidelines adopted from the algorithm of linguistic validation by Mapi Institute.

Stage 1: Forward translation

Two Kannada-English bilingual adult translators whose first language is the Kannada language produced independent translations (Forward translations; F1 and F2). One of the translators was an experienced audiologist with 15 years of research experience, including translation-based studies. The second translator had extensive familiarity with the local culture, but was unaware of the health concepts examined. Hence, clarifications regarding audiology specific terms were provided by researchers to support forward translation. Both the translators made individual comments regarding difficult words/phrases/questions or any such doubts during translation. They also summarized their intentions behind their choices in a written report. Questions, participant, instructions and response options were also translated. Forward translations of all the five questionnaires were completed in about a month and a half.

In this stage, translators incorporated some contextual adaptations apart from the mere translation of questionnaire content. Two major adaptations include: i) retaining a few words in English itself in the parenthesis beside its Kannada translations (just changing the script to Kannada), as colloquial usage of Kannada language includes many English words instead of original (pedantic) Kannada version. A list of words retained in English includes: hearing aid, bazaar, contact lens, TV, radio, club, cards, waitress, party, calling bell, alarm, horn; and ii) considering words with similar meaning in Kannada as a few words could not be literally translated. These words/phrases include: peers, warm relationship, normally, personal care task, and short burst.

Stage 2: Synthesizing a common translation

In this stage, the first author, along with the two forward translators compared both translated versions obtained in Stage 1 and produced a single reconciled translation. Since translators had their own linguistic style and preference for words, the easier, clearer and more colloquial of the two versions was chosen. A written report was produced summarizing the common synthesis process. Attempts were made to resolve issues through consensus. Details of each issue addressed and how they were resolved were documented.

Stage 3: Back-translation

Two adult bilingual translators from a non-medical background independently translated the common synthesized Kannada translations obtained in stage 2 back to English within a month (Back translations; B1 and B2). This helped in detecting inaccuracies in forward translations. An expert panel (discussed below) was involved in the identification of such inaccuracies.

Stage 4: Expert committee review

This committee included forward and back-translators, two experienced audiologists, and a linguist. All members of this panel were Kannada-English bilinguals. The researchers were in close contact with the expert committee during this time. The committee consolidated all the versions to prepare the pre-final version of each questionnaire. The committee reviewed the entire translations, identified the errors and produced a written report regarding decisions taken to reach equivalence. Errors mainly included: i) a few missing parts of translations, which were identified and added; and ii) inappropriate words/phrases/items, which did not capture the concept very well and were modified through consensus. Totally, 11 changes were incorporated in the translations following this stage.

Stage 5: Field testing of pre-final version

This is the last stage before producing the final version of the translated questionnaire. The 37 participants were interviewed using the pre-final versions of all five questionnaires. For each item, participant’s opinion about how he/she interprets the question was collected along with their responses to those questions. If the participant did not understand or wrongly interpreted any word/phrase/question, then how researcher clarified them was also noted. Further, participants were also asked if any questions made them uncomfortable or if they felt any item was not relevant to them. Opinions and responses were analyzed to check the correctness of translation and necessary changes were incorporated to prepare the final version of all the five questionnaires.

There were a few modifications of words/phrases incorporated, as they were found to be unclear or misinterpreted by the participants. A few questions were reported as irrelevant to him or her (e.g., The first question in the PS questionnaire: Do you have equal opportunity to find work as your peers?). However, as researchers found those questions to be relevant to most other participants in the hearing impaired population, they were retained. Also, none of the items were considered uncomfortable/offensive and hence all questions were retained.

Final versions of all the five Kannada translations of the questionnaires (HHQ, IOI-HA, SAC, PS, and AQoL- 4D in the same order) are provided in Appendices 1-5.

Discussion

This study involved translation of five health measures from English to Kannada language following the AAOS translation-adaptation guidelines. The procedure adopted to translate plays an important role in multilingual survey projects.10 Although adopting good translation procedures does not ensure the success of the study, incorrectly translated measures can make data incomparable with normative data obtained in the source language.10 Translation procedures are by itself a challenge faced by researchers.28 This statement is true in the context of this study too, as there were many practical issues and challenges faced during the process of this study. Some of them include: i) not predicting language dialect as a contextual factor during translation; ii) inability to reach clear consensus amongst experts during the expert committee review stages; and iii) unavailability of native English back translators. Details on all these issues along with lessons learned and our practical advice are discussed below in order to provide more insight on cautions that could be exercised during such cross-cultural translations.

The success of instrument translation mainly depends on professional knowledge, linguistic competence and cultural experience of the translators as well as their awareness of the study objectives, concepts of interest and intent of the item.17 In the present study, we followed a team approach by including two forward translators. Thus, unlike single-direct translation, different talents were brought together (like language expert and subject expert) by including two translators, in order to produce the best possible translated version of the questionnaire.

One of the translators, as mentioned before, was naive to discipline (hearing science and health) specific terminologies but was highly proficient in the target language and local culture. Hence, support required in terms of clarifications and explanations was provided during forward translation whenever he expressed a lack of understanding or needed confirmation. We, therefore, suggest having teams (a minimum of two teams) of forward translators, where each team has a minimum of two translators with different backgrounds. This allows translators to interact and exchange their ideas and then construct valid translations. However, caution needs to be taken while making teams to ensure compatibility and consensus between experts within each team, as some experts tend to dominate others within the team while expressing their views.

This study included translation of a total of 58 questions along with their responses. When the number of items that need translation is many (as in this study), split translation method (Schoua-Glusberg as cited in Harkness and colleagues)29 is a better choice. In split translation, the total items are split (with or without overlap) amongst multiple translators. This ensures that the translation process does not burden and fatigue the translators and therefore ensures good quality translations. However, this was not done in this study and this idea emerged only after getting feedback from translators on their experience of the translation process.

Another consideration is the choice of translators’ dialects. India is a multilingual country with many languages and numerous dialects. In the Kannada language, around 20 dialects have been identified. This factor has two important implications; firstly, the choice of the translators (keeping their dialect in mind) and secondly, the appropriateness of generalization or usability of the translated questionnaire in multiple regions within a state (with one regional language and multiple dialects). When the target language has many dialects, it is logical and advisable to include multiple translators and split translation in the process. This could be viewed as one of the procedural limitations of this study as we did not account for dialectical variations in the Kannada language. One of the ways to ensure suitability of the questionnaire to all the dialects of a language is by including participants with different dialects during pre-final testing (stage 5) and obtaining their feedback on comprehension of the original version.

Although it seems ideal to have multiple translators for forward translation and many specialists in expert review committee, reaching consensus to produce a consolidated version was challenging. Translators/experts tend to dispute passionately about the specific literal or conceptual appropriateness of some of the items.30 Previous studies that have translated or adapted questionnaires rarely indicated the method of reaching consensus. Thus, it would be appropriate to highlight this issue in order to give more insight. In the present study, we reached consensus by the majority. When consensus could not be reached, value was given to the opinion of the majority in the panel.

It is an advisory practice to keenly inspect the forward translations before considering them to synthesize a common translation. Each measure has various sections and some translators might miss out translating some parts (e.g., some words or phrases). Thus, inspecting the translations thoroughly before common translation synthesis may facilitate guarding against the possible threat of including items in a single translation version as standard (due to missing gaps in the alternative translation) in the reconciled edition. Such gaps were noticed in the forward translations in this study through inspection and were filled up before the second stage.

During the process of combining forward translations to generate a single common translation, words/phrases other than those in the actual translations might strike as the better choice to the experts. It is not incorrect to have them included in the synthesized version. In this study also, there were a few new words/phrases added as alternatives to the forward translators’ original version as those words/phrases were found to better fit the context.

The back translation process follows the generation of a common translation step. AAOS guidelines recommend that back translations are done by two English-Kannada bilinguals with English as their first language. However, in the present study, due to the unavailability of such back translators, we included a linguist and a professor, who had completed their education in English and use English as the medium of communication in everyday work.

Reports and documentation are equally crucial components of this entire process, often overlooked. During this study process, it was noticed that, aspects highlighted in the translator’s written report are the most common issues discussed during the review and amendment sessions. Revision is an integral and ongoing process throughout the procedure.31 One of the learned lessons was that the written reports (during all the sub-stages) were crucial in making improvements incorporated in the final version.

In summary, we learned through experience that in spite of the availability of many standard procedures for translation-adaptation process, each cross-cultural study experiences its own unique challenges. Each limitation may call for a different solution in order to overcome, and such solutions, though not always perfect, should not be disregarded.12 Evaluation of the psychometric properties of these questionnaires (i.e., construct validity, concurrent validity, predictive validity, internal consistency, reliability and repeatability), beyond the scope of the present study, must be studied before these measures can be used for research and clinical purpose. This will be the goal of our upcoming studies.

Conclusions

The objective of the present study was to translate and adapt five English self-report health measures to a South Indian language, Kannada. The AAOS recommended guidelines, which is a well accepted systematic translation-adaptation procedure, was followed cautiously. The adopted procedure ensured thematic and/or conceptual equivalence, rather than a literal translation of questionnaire items. Translated versions of the five health measures are provided for interested readers, along with the explanations of challenges faced during the translation-adaptation process. The description of adopted procedures can be of help to researchers and clinicians around the world while translating and adapting a standard questionnaire from other languages. Evaluation of psychometric properties is essential for clinical and research use and work is currently underway.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere appreciation and gratitude to all the translators, research participants, and volunteers involved in the study. We also thank the All India Institute of Speech and Hearing for its support in data collection.

Appendices

See the following online Appendices:

Appendix 1: Hearing handicap questionnaire (HHQ) - translated Kannada version.

Appendix 2: International outcome inventory - Hearing aids (IOI-HA) - translated Kannada version.

Appendix 3: Self-assessment of communication (SAC) - translated Kannada version.

Appendix 4: Participation scale (PS) - translated Kannada version.

Appendix 5: Assessment of quality of life (AQoL) - translated Kannada version.

References

- 1.Bhat N, Shewala SS, Kasat DP, Tawade HS. Survey on hearing aid use and satisfaction in patients with presbycusis. Indian J Otol 2015;21:124-8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor B. Self-report assessment of hearing aid outcome - an overview; 2007. Available from: http://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/self-report-assessment-hearing-aid-931

- 3.Gatehouse S. The Glasgow hearing aid benefit profile: derivation and validation of a client-centered outcome measure for hearing aid services. J Am Acad Audiol 1999;10:80-103. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatehouse S, Noble W. The speech, spatial and qualities of hearing scale (SSQ). Int J Audiol 2004;43:85-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox R, Hyde M, Gatehouse S, et al. Optimal outcome measures, research priorities, and international cooperation. Ear Hear 2000;21:106S-15S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schow R, Nerbonne M. Communication screening profile: use with elderly clients. Ear Hear 1982;3:135-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Census of India; 2000. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-commoncensusdataonline.html

- 8.Beauford JE, Nagashima Y, Wu MH. Using translated instruments in research. J Coll Teach Learn 2009;6:77-82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol 1970;1:185-216. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harkness J. Guidelines for best practice in cross-cultural surveys, 3rd edition; Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2011. Available from: http://ccsg.isr.umich.edu/pdf/FullGuidelines1301.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments; 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/sub-stance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- 12.Medical Outcome Trust. New translation criteria (Volume 5); 1997. Available from: http://www.outcomes-trust.org/bulletin/0797blltn.htm

- 13.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000;25:3186-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varni JW. Linguistic validation of the PedsQL™-A quality of life questionnaire. Mapi Research Institute; 2002. Available from: http://www.pedsql.org/translations.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hambleton RK, Kanjee A. Enhancing the validity of cross-cultural studies: improvements in instrument translation methods. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, 1993 April 12-16, Atlanta, GA, USA Available from: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED362537 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005;8:94-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck CT, Bernal H, Froman RD. Methods to document semantic equivalence of a translated scale. Res Nurs Health 2003;26:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baeza FLC, Caldieraro MAK, Pinheiro DO, Fleck MP. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation into Brazilian Portuguese of the measure of parental style (MOPS) - a self-reported scale - according to the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) recommendations. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2010;32:159-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristjansson EA, Desrochers A, Zumbo BD. Translating and adapting measurement instruments for cross-linguistic and cross-cultural research: a guide for practitioners. Can J Nurs Res 2003;35:127-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology. IOI-HA list of questionnaires; 2015. Available from: http://icra-audiology.org/Repository/self-report-repository/IOI-HA%20list-of-questionnaires

- 21.Smith SL, Noe CM, Alexander GC. Evaluation of the international outcome inventory for hearing aids in a veteran sample. J Am Acad Audiol 2009;20:374-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Guidelines for audiologic screening [Guidelines]; 2007. Available from: http://www.asha.org/policy/GL1997-00199/

- 23.Millington D. Audiologic rehabilitation practices of ASHA audiologists: survey. Master’s Thesis. Idaho State University, USA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.vanBrakel WH, Anderson AM, Mutatkar RK, et al. The Participation Scale: measuring a key concept in public health. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:193-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevelink SA, Terwee CB, Banstola N, van Brakel WH. Testing the psychometric properties of the participation scale in Eastern Nepal. Qual Life Res 2013;22:137-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Day N, et al. Construction and utility scaling of the assessment of quality of life (AQoL) instrument, Working Paper 101, Centre for Health Program Evaluation, Melbourne, 2000. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/view-doc/download?doi=10.1.1.460.8597&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acquadro C, Conway K, Hareendran A, Aaronson N. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health 2008;11:509-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willgerodt MA, Katoka-Yahiro M, Kim E, Ceria C. Issues of instrument translation in research on Asian immigrant populations. J Prof Nurs 2005;21:231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harkness JA, Villar A, Edwards B. Translation, adaptation, and design. Harkness JA, Braun M, Edwards B, et al., eds., Survey methods in multinational, multicultural and multiregional contexts. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. pp 117-140. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinokurov A, Geller D, Martin TL. Translation as an ecological tool for instrument development. Int J Qual Methods 2007;6:40-58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karthikeyan G, Manoor U, Supe SS. Translation and validation of the questionnaire on current status of physiotherapy practice in the cancer rehabilitation. J Cancer Res Ther 2015;11:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]