Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Assessing and evaluating mental health status can provide educational planners valuable information to predict the quality of physicians’ performance at work. These data can help physicians to practice in the most desired way. The study aimed to evaluate factors affecting psychological morbidity in Iranian emergency medicine practitioners at educational hospitals of Tehran.

METHODS:

In this cross sectional study 204 participants (emergency medicine residents and specialists) from educational hospitals of Tehran were recruited and their psychological morbidity was assessed by using a 28-question Goldberg General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28). Somatization, anxiety and sleep disorders, social dysfunction and depression were evaluated among practitioners and compared to demographic and job related variables.

RESULTS:

Two hundreds and four participants consisting of 146 (71.6%) males and 58 (28.4%) females were evaluated. Of all participants, 55 (27%) were single and 149 (73%) were married. Most of our participants (40.2%) were between 30–35 years old. By using GHQ-28, 129 (63.2%) were recognized as normal and 75 (36.8%) suffered some mental health disorders. There was a significant gender difference between normal practitioners and practitioners with disorder (P=0.02) while marital status had no significant difference (P=0.2). Only 19 (9.3%) declared having some major mental health issue in the previous month.

CONCLUSION:

Females encountered more mental health disorders than male (P=0.02) and the most common disorder observed was somatization (P=0.006).

KEY WORDS: Psychological morbidity, Mental health problem, Goldberg General Health Questionnaire, Short running head, Factors affecting psychological morbidity

INTRODUCTION

Occupational stress is one of the major health hazards and accounts for most of the physical illnesses, substance abuse, and family problems experienced by health care practitioners. Among physicians, occupational stress and stressful working conditions have been linked to low productivity, absenteeism and suicide thus affecting career longevity.[1–5] Generally, health care workers face particular challenges such as more exposure to traumatic events, violence, critical decision making, increased workloads, high demands and limited resources.[1,4,6,7] The incidence of psychological morbidity in emergency medicine practitioners is not known but some studies have indicated that its prevalence in other specialties is about 21%–46%.[6,8–10]

A study by Whitley et al[11] on emergency physicians indicated that the level of depression and stress among them was more than other professions.

Goldberg General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) was first introduced by Goldberg et al in 1972. It has been translated into 38 different languages. This questionnaire can be used as a measure for estimating mental health problems in the society. GHQ-28 was derived from the original 60-item version and prepared mainly for research purposes. GHQ-28 incorporates four subcategories: somatization symptoms, anxiety and sleep disorders, social dysfunction, and major depression. Its 28-question type has been most used in different studies and its reliability and validity have been proved.[12–16] Using GHQ-28 scoring method, a total score ≥4 out of 28 would suggest possible “psychiatric problem”, although a psychiatric assessment would be still needed for proper clinical diagnosis.[12,13]

In Iran, the incidence of psychological morbidity hasn’t been studied yet, so in order to address these concerns and to shed light on psychological morbidity, we conducted this cross sectional study.

METHODS

In this cross sectional study, 204 participants (emergency medicine residents and specialists) of different educational hospitals in Tehran, were recruited. All participants gave consent letters and were all willing to participate in our study. We collected our samples from all emergency medicine residents and attendings of 8 general and tertiary referral centers in Tehran. We received approval from the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. We excluded physicians without consent to participate in our study.

The psychological morbidity in participants was evaluated using GHQ-28. GHQ-28 has been frequently used as an indicator of psychological well-being. It is a well validated self-administered screening test designed to identify short-term changes in mental health status.[12–14] This 28-item questionnaire consisted of 4 subcategories with 7 questions in each. Each question should be answered in a Likert scale: 1 not at all, 2 not more than usual, 3 rather more than usual and 4 much more than usual. After collecting questionnaires, we assigned a score of 0 for either responses 1 or 2 and a score 1 for either responses 3 or 4. Total score ranged from 0 to 28 and higher scores indicated a greater probability of a psychiatric distress. In this way total scores that exceeded 4 out of 28 would suggest probable distress.[12,13]

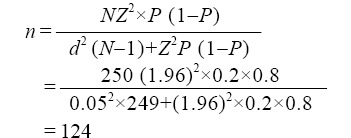

We used the following equation to calculate sample size:

α=1.96, d=0.05, N=study population, P=20%, De=1.5 (design effect), n=sample size

We analyzed all data using SPSS version 20. Categorical and continuous data are presented as numbers (%) and mean±SD respectively. We have used the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test to compare nominal variables and the Student’s t test to compare continuous variables with normal distribution. The relation of two nominal variables was assessed by correlation test. Alpha (α) <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

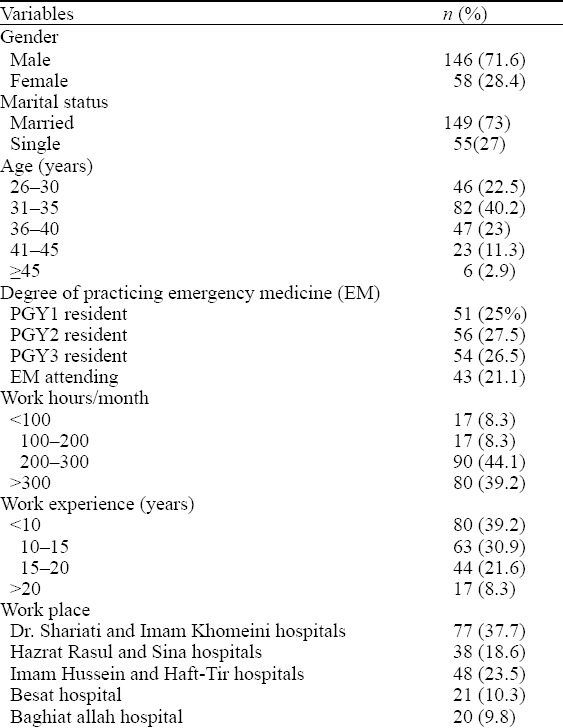

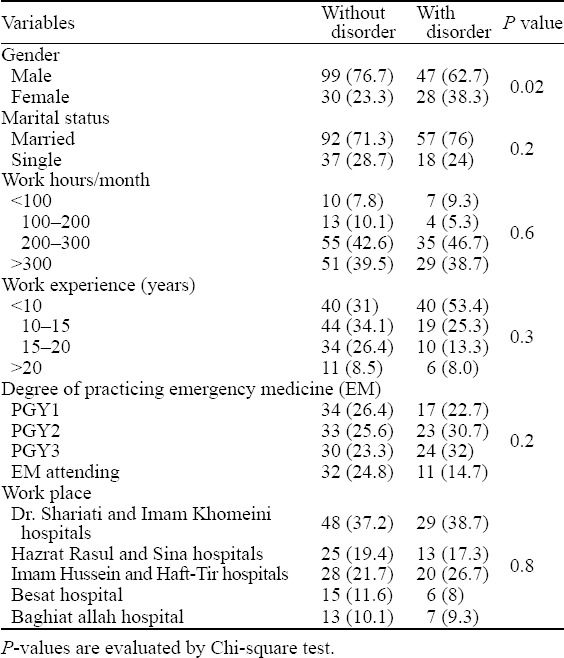

Of the 204 participants enrolled in our study, 146 (71.6%) were males and 58 (28.4%) were female. All demographic and job related variables are shown in Table 1. Among all participants, 19 (9.3%) persons declared that they suffered some mental health problems in the previous month and 185 (90.7%) did not. In our study 75 (36.8%) participants were found to have a potential mental health disorder and 129 (63.2%) were not. Comparison of the relation between this number and our studied variables is shown in Table 2. Males generally encountered more mental health disorders than females (P=0.02).

Table 1.

Demographic and job related variables in participants

Table 2.

Comparison of the relation between having mental health problem with the studied variables, n (%)

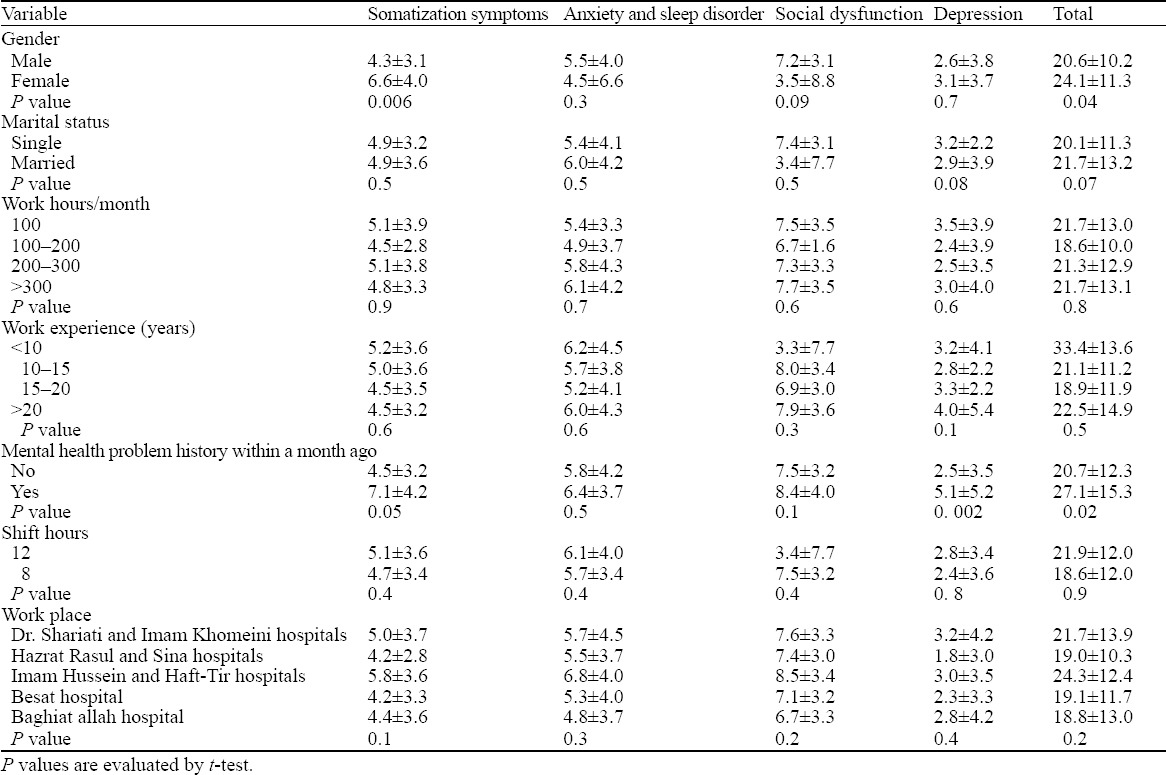

The mean scores for somatization symptoms, anxiety and sleep disorder, social dysfunction and depression were 4.9±3.5, 5.8±4.1, 7.6±3.3 and 2.7±3.7 respectively. The mean total score was 21.3±12.7. Comparison of the mean scores of 4 subcategories with studied variables is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the mean scores of 4 subcategories with studied variables

We did not find any significant difference between total scores of single and married participants however, there was a significant difference between male and female physicians mean total score (P=0.04). Furthermore, the score of somatization symptoms was significantly higher in females than males (P=0.006).

Participants with a history of previous mental health problem, were more exposed to depression than ones without (P=0.002). On the other hand the former group’s total score was significantly more than the latter (P=0.02).

DISCUSSION

In emergency departments, physicians are usually faced with unpredictable stress that may lead to dissatisfaction, low morale and poor work performance. Occupational stress inadvertently leads to inappropriate performance.[15] Job stress has belittling impact on physicians’ motivation thus it can have dire consequences on their health.[16] High levels of stress result in low productivity, increased absenteeism, alcoholism, drug abuse, hypertension and cardiovascular problems.[17] Personality predisposing factors may contribute to feelings of job dissatisfaction and stress.[18] In Iran, emergency medicine (EM) is one of the newest medical specialties thus few studies have been conducted in this field. Our study was designed to evaluate the GHQ-28 scale in emergency physicians of Tehran educational hospitals. The most important finding in this study was the high rate of psychological disorders compared to previous reports. We found that 36.8% of participants had psychiatric disorders. The rate of psychiatric disorders in a study by Burbeck et al[19] was more than our results (44% vs. 36.8%). The reason for such a discrepancy might be related to different tools used for analyzing, different patients sampling and study design. We did not find any specific factor related to stress, however, the number of hours participants worked in a shift was related to stress based on the Burbeck study.[19]

Our study showed that the rate of psychiatric disorders in female participants was significantly more than males (P=0.02). Moreover, in females the score of somatization was significantly more than males (P=0.006). Yogev et al[20] also indicated that female doctors, in emergency departments, are more at risk of psychiatric disorders than males.

Another study evaluated level of depression, anxiety and stress in interns and it was revealed that frequent calls during night shift, long working hours, heavy workload, marriage and having children were the most significant stressors.[21] We had considered marriage as an effective factor but after analysis we did not notice such an effect in any groups of our study.

Psychiatric disorders and its associated consequences have been reported to be more prevalent among the medical professions compared to the general population.[22] The causes of these disorders, in medical trainees, are not clear. In this regard there are two hypothesis which might be the possible explanation. First, medical doctors have some traits that may lead to more distress such as obsession, self-doubt, guilt, excessive fear of failure or making mistake, and an exaggerated sense of responsibility.[23] Second, there are many environmental factors associated with stress like the level of standard care at different hospitals, medical team organization, consultant supervision, education and feedback. Working hours in the current survey was not the source of stress. [23] One longitudinal study on young physicians declared that work stress increased during the early career, mainly due to a lack of adaptive behavior in reduction of work hours. This study specified that broken sleep and poor quality of sleep could be underlying causes of stress.[24]

El-Gilany et al[25] evaluated effects of socio-demographic factors on medical students’ stress and they confirmed that stress, anxiety and depression were all frequent among medical students. Another study was conducted on medical and dental students and concluded that work stress levels depended significantly on the type of profession and time of work experience.[26] It seems that counseling and preventive mental health services should be an integral part of the routine clinical facilities caring for medical students or physicians.

Limitation of the study

The main limitations of our study were small sample size and short duration of follow-up. Furthermore we did not include a control group to compare the prevalence of psychiatric disorders with the general population. Further controlled investigations are recommended with longer follow-up to validate findings reported here.

In conclusion, females encountered more mental health disorders than males (P=0.02). We did not find any significant difference between total scores of single and married participants, however, there was a significant difference between male and female physicians mean total score (P=0.04). Furthermore, in females, the score of somatization symptoms was significantly more than males (P=0.006).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to express their gratitude and thanks to the staff members of Imam Khomeini, Dr. Shariati and Imam Hussein hospitals for their constructive support throughout the study, without which this project would have been impossible.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare there is no competing interest related to the study, authors, other individuals or organizations.

Contributors: Saeedi S proposed the study and wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin PJ, Dodd M, Wrate RM. Young doctors’ health—II. Health and health behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrud P. Counselling needs and experience of junior hospital doctors. BMJ. 1990;300:445–447. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6722.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthrie EA, Black D, Shaw CM, Hamilton J, Creed FH, Tomenson B. Embarking upon a medical career: psychological morbidity in first year medical students. Med Educ. 1995;29:337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pino M, Lopez JJ. Stress and adjustment at the beginning of postgraduate medical training. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines. 1995;23:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart SM, Betson C, Marshall I, Wong CM, Lee PW, Lam TH. Stress and vulnerability in medical students. Med Educ. 1995;29:119–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caplan RP. Stress, anxiety, and depression in hospital consultants, general practitioners, and senior health service managers. BMJ. 1994;309:1261–1263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dua JK. Level of occupational stress in male and female rural general practitioners. Aust J Rural Health. 1997;5:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.1997.tb00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blenkin H, Deary I, Sadler A, Agius R. Stress in NHS consultants. BMJ. 1995;310:534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6978.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapur N, Borrill C, Stride C. Psychological morbidity and job satisfaction in hospital consultants and junior house officers: multicentre, cross sectional survey. BMJ. 1998;317:511–512. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7157.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, Cull A, Gregory WM. Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet. 1996;347:724–728. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitley TW, Allison EJ, Jr, Gallery ME, Cockington RA, Gaudry P, Heyworth J, et al. Work-related stress and depression among practicing emergency physicians: an international study. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:1068–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg D, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. NFER NELSON Publishing company Ltd Windsor; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9:139–145. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanderman R, Stewart R. The assessment of psychological distress: Psychometric properties of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) Int J Health Sci. 1990;1:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Vahtera J. Organizational justice: evidence of a new psychosocial predictor of health. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:105–108. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mimura C, Griffiths P. The effectiveness of current approaches to workplace stress management in the nursing profession: an evidence based literature review. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:10–15. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meneze MM. The Impact of Stress on productivity at Education Training &Development Practices. Sector Education and Training Authority. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michie S, Williams S. Reducing work related psychological ill health and sickness absence: a systematic literature review. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:3–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burbeck R, Coomber S, Robinson SM, Todd C. Occupational stress in consultants in accident and emergency medicine: a national survey of levels of stress at work. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:234–238. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.3.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yogev S, Harris S. Women physicians during residency years: workload, work satisfaction and self concept. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:837–841. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam TP, Wong JGWS, Ip MSM, Lam KF, Pang SL. Psychological well-being of interns in Hong Kong: What causes them stress and what helps them. Med Teach. 2010;32:E120–E6. doi: 10.3109/01421590903449894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pullen D, Lonie CE, Lyle DM, Cam DE, Doughty MV. Medical care of doctors. Med J Aust. 1995;162:481–484. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb140011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harari E. The doctor’s troubled marriage. Aust Fam Physician. 1998;27:999–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rovik JO, Tyssen R, Hem E, Gude T, Ekeberg O, Moum T, et al. Job stress in young physicians with an emphasis on the work-home interface: a nine-year, nationwide and longitudinal study of its course and predictors. Ind Health. 2007;45:662–671. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Gilany AH, Amr M, Hammad S. Perceived stress among male medical students in Egypt and Saudi Arabia: effect of sociodemographic factors. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:442–448. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy RJ, Gray SA, Sterling G, Reeves K, DuCette J. A Comparative Study of Professional Student Stress. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:328–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]