Abstract

We examined the late positive potential (LPP) event related potential in response to social and nonsocial stimuli from 9-19 years old youth with (n = 35) and without (n = 34) ASD. Social stimuli were faces with positive expressions and nonsocial stimuli were related to common restricted interests in ASD (e.g., electronics, vehicles, etc.). The ASD group demonstrated relatively smaller LPP amplitude to social stimuli and relatively larger LPP amplitude to nonsocial stimuli. There were no group differences in subjective ratings of images, and there were no significant correlations between LPP amplitude and ASD symptom severity within the ASD group. LPP results suggest blunted motivational responses to social stimuli and heightened motivational responses to nonsocial stimuli in youth with ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, social, restricted interests, late positive potential, motivation

Social communicative impairments are a defining feature of autism spectrum disorder (ASD; APA, 2013). These deficits are evident in the domains of social cognition (e.g., theory of mind), social perception, and social attention (Levy, Mandell, & Schultz, 2009). Recently, there has been increased interest in examining the impact of motivational factors on social functioning in ASD. The “social motivation” hypothesis of autism posits that disrupted social motivational mechanisms may constitute a primary deficit in ASD with potential downstream effects on the development of social impairments (Chevallier, Kohls, Troiani, Brodkin, & Schultz, 2012; Dawson, Webb, & McPartland, 2005; Kohls, Chevallier, Troiani, & Schultz, 2012). Decreased social motivation is clearly not the only mechanistic account of the full range of social deficits associated with ASD (e.g., some individuals with ASD have social interests and actively seek social interactions but fail to form friendships due to impaired social cognition and pragmatic language). However, even during the first year of life, infants who go on to develop ASD demonstrate infrequent orienting to their own name and diminished eye contact (Ozonoff et al., 2010), suggesting that decreased social interest early in life may interfere with the development of social cognition in at least a significant proportion of those with ASD.

Differences in Attention to Social and Non-Social Stimuli in ASD

One corollary of the social motivation hypothesis of autism is that individuals with ASD find nonsocial information, rather than social information, to be highly salient (Klin, Jones, Schultz, & Volkmar, 2003; Klin, Jones, Schultz, Volkmar, & Cohen, 2002). This “nonsocial bias” may lead to increased preference for, and in turn interaction with, the nonsocial environment to the detriment of social development, potentially contributing to the emergence of restricted interests. Restricted interests (RIs) are a component of restricted and repetitive behavior symptoms in ASD (APA, 2013) and refer to the tendency for nearly all individuals with ASD to develop unusually strong interests, attachments, and preoccupations for idiosyncratic topics or objects (Lam, Bodfish, & Piven, 2008). These interests are more intense and less flexible than interests in typically developing children and often interfere with the development of social relationships (Klin, Danovitch, Merz, & Volkmar, 2007; Turner-Brown, Lam, Holtzclaw, Dichter, & Bodfish, 2011).

Additionally, whereas the social motivation theory of ASD suggests that neural systems supporting motivation and attention may be hyporesponsive to social stimuli in ASD (Delmonte et al., 2012; Scott-Van Zeeland, Dapretto, Ghahremani, Poldrack, & Bookheimer, 2010; Yirmiya, Kasari, Sigman, & Mundy, 1989), these same neural systems may be hyperresponsive to certain classes of nonsocial stimuli in ASD (Cascio et al., 2014). This mechanistic account of RIs in ASD explains why individuals with ASD may exhibit positive affect in response to specific nonsocial aspects of the environment (Attwood, 2003; Sasson, Dichter, & Bodfish, 2012) and may even engage in increased joint attention (Vismara & Lyons, 2007) and eye contact (Nadig, Lee, Singh, Bosshart, & Ozonoff, 2010) when such RIs are incorporated into social interactions. These clinical features suggest that social motivation deficits and RIs in ASD may both be causally linked to abnormal reward-based responses to social and nonsocial information.

ERP Indices of Attention in ASD

Motivational responses to RIs in ASD have been studied using self-report (Sasson et al., 2012), functional neuroimaging (Dichter et al., 2012), and physiological methods (Dichter, Benning, Holtzclaw, & Bodfish, 2010; Louwerse et al., 2014). However, to date, there have been no published event related potential (ERP) studies of RIs in ASD. This lack of research stands in contrast to the growing ERP literature addressing responses to social stimuli in ASD, which have mostly focused on the P300 response, reflecting stimulus evaluation, novelty detection, and categorization, and the N170 response that is associated with facial recognition responses (Dawson et al., 2005; Devitt, Gallagher, & Reilly, 2015; Luckhardt, Jarczok, & Bender, 2014). These studies have generally found longer N170 latencies to faces (but not objects) in ASD (Cygan, Tacikowski, Ostaszewski, Chojnicka, & Nowicka, 2014; Dalton, Holsen, Abbeduto, & Davidson, 2008; McPartland et al., 2011), a lack of N170 modulation by directed attention to faces in ASD (Gunji, Inagaki, Inoue, Takeshima, & Kaga, 2009), diminished N170 amplitude in the right hemisphere to faces and lack of P300 amplitude differences between self and other faces in ASD (Gunji et al., 2009), and greater P100 and N170 amplitude to faces versus houses and lack of differentiation of responses to upright vs inverted faces (Webb et al., 2012). More recent work has found attenuated P3 response during the anticipation of social, but not non-social, rewards in typically developing young adults with high levels of autistic traits (Cox et al., 2015).

One ERP component that has not been evaluated in ASD but that has particular relevance to the social motivation hypothesis of ASD is the late positive potential (LPP) ERP component in response to faces and objects. The LPP is a centro-parietal ERP positive component that initiates around 300 ms after stimulus onset and lasts for several hundred milliseconds (Cuthbert, Schupp, Bradley, Birbaumer, & Lang, 2000). The LPP response is greater in response to a range of positive and negative affective stimuli relative to neutral stimuli (Fischler & Bradley, 2006; Herbert, Junghofer, & Kissler, 2008; Schacht & Sommer, 2009) and has been suggested to reflect a variety of mechanisms, including sustained attention (Cuthbert et al., 2000; Weinberg, Ferri, & Hajcak, 2013), motivational responses (Keil et al., 2002; Schupp et al., 2007), and attentional resources (Citron, 2012). The LPP is responsive to both emotionally positive and negative stimuli and thus is considered to reflect the enhanced motivation and arousal that is experienced in response to affective stimuli rather than their emotional valence (i.e., elicited by positive and negative emotions) per se (Cuthbert et al., 2000). However, in contexts where only one valence category is presented, the LPP has been interpreted to reflect, at least in part, stimulus valence as well (Bayer & Schacht, 2014; Herbert, Kissler, Junghofer, Peyk, & Rockstroh, 2006).

Current Study

In the present study, social stimuli (images of faces) and nonsocial stimuli (images of objects related to RIs in ASD) were presented to children and adolescents with ASD to evaluate LPP amplitudes to these two classes of stimuli. Social stimuli were smiling faces. The nonsocial image set was designed to reflect common RIs in ASD, and a previous report has shown that individuals with ASD rated this image set to be more pleasing than did individuals without ASD (Sasson et al., 2012). The LPP response was examined as an index of positive motivational responses and salience to these two classes of stimuli. Given previous findings of decreased orienting to social stimuli (Dawson, Meltzoff, Osterling, Rinaldi, & Brown, 1998; Klin, Lin, Gorrindo, Ramsay, & Jones, 2009) and increased orienting to the same set of nonsocial stimuli used in the present study (Sasson & Touchstone, 2014), we hypothesized that the ASD group would be characterized by decreased LPP amplitude to social stimuli and increased LPP amplitude to nonsocial stimuli. We further hypothesized that LPP amplitude in the ASD group would predict the magnitude of core ASD symptoms.

Method

Participants

A total of 39 participants with ASD (5 female) and 35 control (5 female) participants were recruited for this study. Data were not analyzable from four participants with ASD and one control participant because discomfort with skin abrasion yielded unacceptably high impedances (>30 kΩ). The final ASD sample consisted of 35 children and adolescents with ASD and 34 controls 9-19 years old who participated in the following: (a) a diagnostic and symptom evaluation; (b) an electroencephalogram (EEG) recording session; and (c) a ratings session during which they provided subjective ratings of valence and arousal of the experimental images.

Participants consented to a protocol approved by the local human investigations committee at UNC-Chapel Hill. All ASD participants had clinical diagnoses of ASD that were confirmed through the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G; Lord et al, 2000) administered by trained research staff supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist and using standard cutoffs. Because both Module 3 and Module 4 were used (Module 3: 16 participants, Module 4: 19 participants), calibrated severity scores were calculated from raw ADOS-G scores to obtain a dimensional measure of ASD symptom severity across both modules (Gotham, Pickles, & Lord, 2009; Hus & Lord, 2014). Both groups also completed the Social Responsiveness Scale (Constantino & Gruber, 2002), which is a dimensional measure of overall ASD symptom severity. They also completed the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (Bodfish, Symons, & Lewis, 1999), which is a dimensional measure of repetitive behavior severity in ASD. Control participants scored below the recommended cutoff of 15 on the Social Communication Questionnaire (Mulligan, Richardson, Anney, & Gill, 2009).

Diagnostic groups did not differ in terms of age or intelligence quotient scores (derived from the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test; (KBIT; Kaufman, 1990)), all ps > .05 (see Table 1). Fourteen children in the ASD group were on psychotropic medication, including psychostimuluants (Vyvanse, Adderall, Focalin), atypical anti-depressants (Bupropion), antihypertensives/central alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (Tenex, Clonidine, Intuniv), benzodiazepines (Klonopin), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Prozac, Zoloft), mood stabilizers (Depakote), and atypical anti-psychotics (Risperdal, Abilify).

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

| Variable | ASD (n = 35) | Control (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.4 (3.2) | 13.3 (2.9) |

| ADOS Total Score | 15.4 (3.5) | · |

| ADOS Calibrated Severity Score a | 8.17 (1.4) | · |

| SRS | ||

| Total Score* | 73.8 (7.9) | 57.7 (3.7) |

| Awareness | 8.9 (2.6) | 10.4 (2.3) |

| Cognition* | 17.0 (4.3) | 11.2 (2.3) |

| Communication* | 27.0 (6.4) | 17.1 (3.0) |

| Mannerisms* | 17.3 (5.6) | 1.7 (1.6) |

| Social Motivation* | 13.6 (3.6) | 9.4 (2.7) |

| RBS-R | ||

| Total Score* | 24.1 (12.5) | 0.5 (1.3) |

| Stereotyped Behavior* | 3.4 (2.2) | 0.1 (0.3) |

| Self-Injurious Behavior* | 1.4 (1.5) | 0.0 (0.1) |

| Compulsive Behavior* | 3.45 (3.7) | 0.2 (0.7) |

| Ritualistic Behavior* | 5.17 (4.0) | 0.0 (0.3) |

| Sameness Behavior* | 7.0 (5.9) | 0.2 (0.5) |

| Restricted Behavior* | 2.7 (1.1) | 0.1 (0.2) |

| Full Scale IQ | 104.6 (17.5) | 113.7 (14.1) |

| Verbal IQ | 103.1 (17.4) | 111.3 (14.0) |

| Performance IQ | 104.5 (16.9) | 111.9 (12.9) |

Note.

p < .001.

ASD = autism spectrum disorder.

Standardized severity scores on a scale of 1-10 calculated from raw Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) scores (Gotham et al., 2009; Hus & Lord, 2014).

SRS = Social Responsiveness Scale (Constantino & Gruber, 2002), RBS-R = Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (Bodfish et al., 1999), IQ = Intelligence Quotient derived from the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT).

Stimulus Materials

All visual stimuli were presented in color and had a resolution of 1024×768. Each participant viewed one of two possible sets of images, the presentation of which was counter-balanced across participants. Each participant viewed ten social stimuli and ten nonsocial stimuli. Participants were instructed to view each image as they normally would and to try to look at the image the entire time it was on the screen.

Social stimuli

Social stimuli consisted of Happy-Direct Gaze Closed Mouth Female NimStim images (Tottenham et al., 2009), a standardized set of faces. Half of the images depicted White faces. The identifiers of the NimStim images used were: 01, 02, 03, 05, 06, 07, 08, 09, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19 from the “F_HA_C” set.

Nonsocial stimuli

A set of nonsocial stimuli were used that have been developed to be related to common RIs in ASD. Although the RIs of individuals with ASD are, by definition, idiosyncratic, a standardized image set of images related to common RIs in ASD (e.g., trains and electronics) was used to allow all participants to view the same images (images are presented in the Appendix of Dichter et al., 2012). These images were derived from categories of common RIs in ASD (South, Ozonoff, & McMahon, 2005). They have been shown to differentially activate brain reward circuitry in ASD (Dichter et al., 2012), elicit great visual attention in children and adults with ASD (Sasson, Elison, Turner-Brown, Dichter, & Bodfish, 2011; Sasson & Touchstone, 2014), have been rated as more pleasant by individuals with ASD (Sasson et al., 2012), and have been shown to elicit greater valuation by individuals with ASD (Watson et al., 2015).

Procedure

Participants saw 20 images twice each (once for EEG recording and once to provide subjective ratings). Picture presentation was controlled by the E-Prime v1.1 software package (Psychology Software Tools Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). During EEG recording, participants viewed each image for six seconds with an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 10 seconds, with a fixation cross presented between stimuli. These durations were chosen to be consistent with our previous work on affective startle modulation in autism (Dichter et al., 2010). The mood states induced by neutral images are very brief (Dichter, Tomarken, & Baucom, 2002). Thus, there is likely no effect of the inclusion of other images on affective responses given the 10 second ITI. Presentation was pseudo-random such that the same picture category was never repeated more than twice in a row and pictures of each category were equally distributed throughout the session. Pictures were displayed on a 21 inch color monitor approximately 1.0 m in front of the participant, resulting in a visual angle of the monitor of 30 degrees, though images did not fill the entire screen. There were two sets of stimuli that contained non-overlapping images, and image set was counterbalanced across participants. Participants were monitored via infrared camera throughout the recording sessions, and the experimenter ensured that all participants attended to the pictures during the entire ERP recording session.

After EEG was recorded, the EEG cap was removed, the pictures were presented a second time, and participants rated each picture with respect to pleasure and arousal using 9-point scales. During the rating procedures, participants controlled the duration of picture exposure, though viewing time data were not recorded. The range and direction of the ratings for Valence were -4 (extremely unpleasant) to +4 (extremely pleasant) and for Arousal were 0 (not at all aroused) to +8 (extremely aroused).

Electroencephalography Data Recording and Data Reduction

Data were acquired with a Neuroscan (Compumedics, Charlotte, USA) SynAmps2 64-channel system and were sampled at 2000 Hz with alternating current (AC),with a gain of 2010 and an impedance threshold for recording of 10 kΩ. An online bandpass filter from 0.05-500 Hz was used, and data were recorded from 9 channels (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, P4) using the standard 10–20 international system (Jasper, 1958; American Electroencephalographic Society, 1994) with a Neuroscan 64 channel Ag-AgCl Electro-Cap. Only nine sites (in addition to mastoid, VEO, and HEO sites) were used to decrease the time required to apply the electrode cap in this initial study, which used a low impedance system that required preparation at each electrode site. Data were referenced to linked mastoids and epoched between 250 ms pre-stimulus to 1550 post stimulus; 50 ms of data on each end of the epoch were included to buffer against filtering artifacts in subsequent processing. Epoched data were analyzed offline after applying a 0.01 Hz high-pass and a 64 Hz low-pass filter at 24 dB/octave. Artifacts from eye movements were corrected using the ARTCOR procedure in SCAN v4.5 based on a 10% threshold at VEO (see Heritage & Benning, 2013). The data were baseline corrected from 200 ms pre-stimulus and analyzed. LPP amplitude was defined as the mean voltage from 800 ms to 1500 ms post-stimulus onset relative to baseline.

Data Analysis

Data from all 20 images viewed by each participant were included in analyses. The omnibus analyses of interest were 2×2 repeated measures ANOVAs with Group (ASD, control) as the between-participants factor and stimulus Category (Social, Nonsocial) as the within-participants factor. This analysis was performed on LPP amplitude, valence ratings, and arousal ratings with effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (ηp2). Significant interaction tests were followed by independent samples t tests comparing groups on responses to social and nonsocial stimuli with effect sizes reported as Hedges' g. Finally, relations between LPP amplitude and symptom severity in the ASD sample were evaluated by correlations conducted separately for LPP amplitude in response to social and nonsocial stimuli with SRS and RBS-R total scores.

Results

Gender, Age, and Picture Set Effects on LPP Amplitude

There were no significant main effects or interactions involving gender, age, or picture set on LPP amplitude. Thus, age, gender, and picture set were excluded from all analyses reported below.

Valence and Arousal Ratings

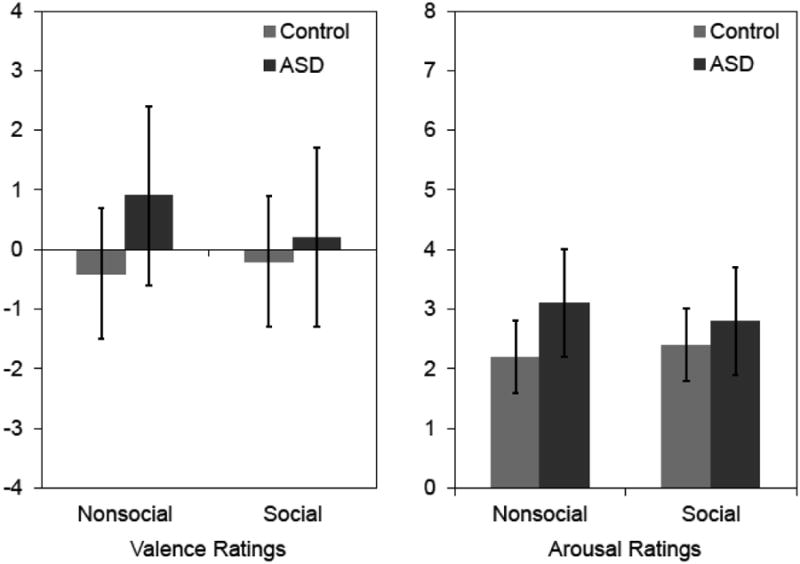

Mean valence and arousal ratings are presented in Figure 1. Ratings data from four ASD participants indicated inadequate comprehension of the ratings procedure (the same rating was endorsed for every image or valence and arousal ratings were perfectly correlated) so they were excluded from the analysis of ratings data. Regarding valence ratings, there was no main effect of Category, F(1,63) = 1.04, p = .312, ηp2 = .02, no main effect of Group, F(1,63) = 1.42, p = .238, ηp2 = .02, and no interaction effect, F(1,63) = 0.42, p = .519, ηp2 = .01. Likewise, with respect to arousal ratings, there was no main effect of Category, F(1,63) = 0.40, p = .529, ηp2 = .01, no main effect of Group, F(1,63) = 2.07, p = .155, ηp2 = .03, and no interaction effect, F(1,63) = 0.07, p = .792, ηp2 = .00.

Figure 1.

Valence (left) and arousal (right) ratings of ASD and control groups. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. The range and direction of valence ratings are -4 (extremely unpleasant) to +4 (extremely pleasant). The range and direction of arousal ratings are 0 (not at all aroused) to +8 (extremely aroused).

LPP Amplitude

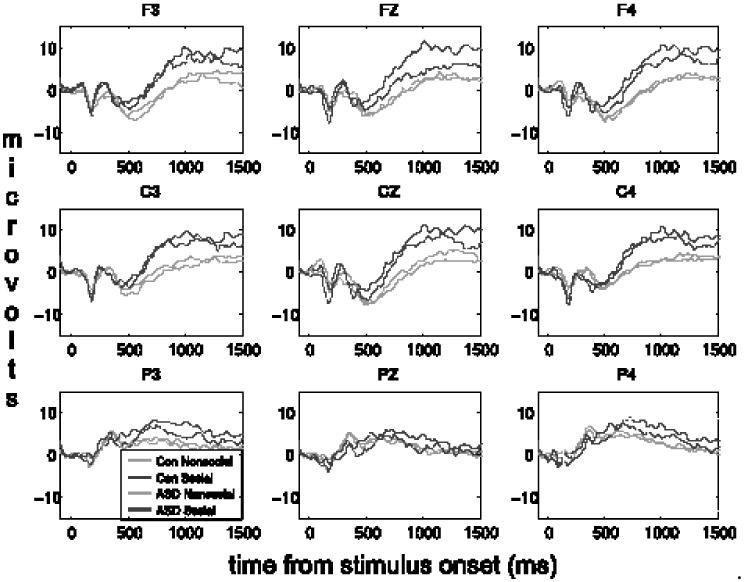

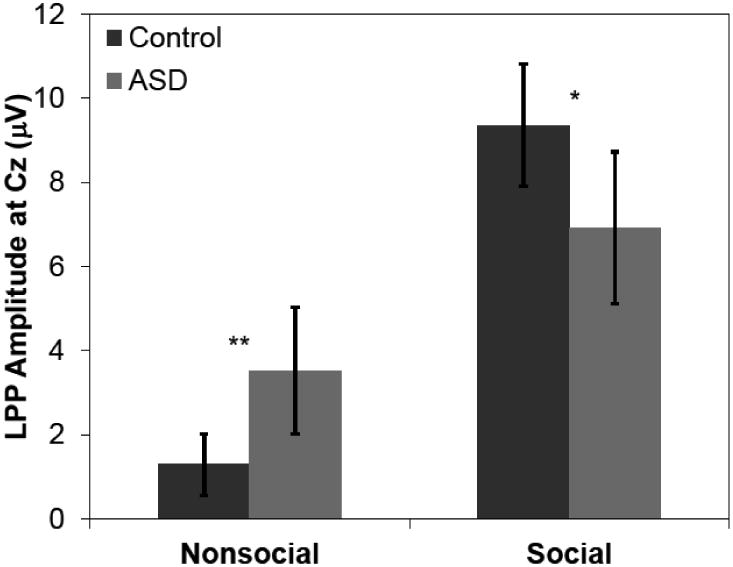

LPP amplitudes at all nine electrode sites that were recorded are presented in Figure 2. Because the LPP is a midline response (Cuthbert et al, 2000), a priori analyses focused on the Fz, Cz, and Pz electrodes. Furthermore, because there was a significant Category × Electrode interaction in a preliminary ANOVA, F(2, 66) = 6.74, p = .002, ηp2 = .17, we analyzed data separately for each electrode. At Cz, there was a Group × Category interaction, F(1,67) = 4.00, p = .049, ηp2 = .06, which reflected that Group status moderated LPP amplitude to Social and Nonsocial images. Follow-up between-groups t tests (see Figure 3) revealed that compared to controls, the ASD group had relatively smaller LPP amplitudes to social images, t(67) = -3.23, p = .002, g = -0.32, and relatively larger LPP amplitudes to nonsocial images, t(67) = 1.99, p = .050, g = 0.21. This interaction substantially qualified the main effect of Category, F(1,67) = 22.7, p < .001, ηp2 = .25, in which social stimuli elicited larger LPP amplitudes than non-social stimuli. There was no main effect of Group, F(1,67) = 0.01, p = .921. There were no main effects or interactions at Fz or Pz, ps > .15.

Figure 2.

Grand average waveforms for ASD and control (“Con”) groups while viewing social and nonsocial images at the nine electrode locations recorded (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4).

Figure 3.

Average LPP amplitude for ASD and control groups in response to social and nonsocial images. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean. * p < .05, ** p < .01.

Relations between LPP Amplitude and ASD Symptoms

There were no significant correlations between LPP amplitudes at Cz to social or nonsocial stimuli and picture ratings or SRS or RBS-R total or subscale scores either across both groups combined or within both groups (uncorrected rs < .21, ps > .20). Similarly, there were no significant correlations between LPP amplitudes at Cz to social or nonsocial stimuli and ADOS severity scores within the ASD group (uncorrected ps > .60).

Discussion

This study investigated LPP responses in children and adolescents with ASD in response to social and nonsocial stimuli. Social stimuli were pictures of smiling faces and nonsocial stimuli were a set of images previous developed around common RIs in ASD. The LPP ERP response occurs in response to a range of positive and negative affective stimuli (Fischler & Bradley, 2006; Herbert et al., 2008; Schacht & Sommer, 2009) and has been suggested to reflect enhanced motivation and arousal that is experienced in response to affective stimuli (Cuthbert et al., 2000; Keil et al., 2002; Schupp et al., 2007). Additionally, in contexts where only one valence category is presented (e.g., only pleasant stimuli), the LPP has been interpreted to reflect stimulus valence as well as motivation (Bayer & Schacht, 2014; Herbert et al., 2006); thus, in the present context, we interpret the LPP response to reflect motivation responses to social and nonsocial stimuli.

Dissociation of Electrophysiological and Self-Report Reactivity to Social and Nonsocial Stimuli

Group status moderated LPP amplitudes at Cz to social and nonsocial stimuli such that the ASD sample demonstrated relatively smaller responses to social stimuli and relatively larger responses to nonsocial stimuli compared to the control group. Because the LPP is an index of motivation and arousal, these findings indicate relatively blunted motivational responses to images of faces in ASD and relatively enhanced motivational responses to nonsocial stimuli related to RI in ASD compared to the control group. More broadly, these findings are consistent with the social motivation hypothesis of autism that posits decreased motivation for social stimuli in ASD. Moreover, these findings extend this account, suggesting that brain systems processing motivational responses may be co-opted in ASD to be hyper-responsive to certain nonsocial stimuli related to RIs in ASD.

However, the ASD and control groups did not differ in subjective ratings of valence or arousal to the images. This stands in contrast to the findings of Sasson et al. (2012) that reported higher valence ratings of these same nonsocial stimuli by a larger sample of adults self-identifying as having an ASD. In this regard, we note that the present sample included only children and adolescents, and also that the significantly larger sample size in Sasson et al. (2012) (i.e., 213 controls, 56 with ASD) provided more power to find statistically significant effects. Despite these sample differences, the fact that LPP responses showed differential modulation by these nonsocial images in ASD and control groups illustrates that this brain potential response may be a potentially more sensitive indicator of motivational responses to images related to RIs in ASD than subjective self-report. A similar pattern of disconnect between subjective and brain responses was reported in Dichter et al. (2012), a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study of responses to this same images set.

Limitations and Future Directions

We opted to use a standard set of nonsocial images related to RIs rather than images of each child's specific RI. RIs are, by definition, idiosyncratic and person-specific, and idiosyncratic RIs have been used in prior ASD studies (Cascio et al., 2014); nonetheless, the use of a standardized set of images allowed for increased internal validity because stimuli viewed by different participants did not differ in semantic content or visual features (e.g., luminance, contrast, etc.) and did not contain any depictions of faces. Importantly, because significant group differences were found in LPP responses using a standard set of images, these findings may be more pronounced using idiosyncratic and child-specific images. Future research that directly compares responses to child-specific RIs versus a standard set of nonsocial stimuli related to RIs will be needed to evaluate this possibility. Additionally, the use of child-specific RIs may have the potential to reveal subtle brain potential responses that may not be detectable using a standard set of images. We also note that presenting pictures for six seconds each is longer than some other ERP studies (e.g., Eisenbarth et al., 2013), potentially resulting in more artifacts than if images were presented for briefer amounts of time. Finally, we acknowledge that this study had a relatively broad age range and that over half of participants in the ASD group were taking medications, and future studies aimed at replicating and extending this work should focus on a narrower age range of participants who are medication-free.

Despite this potential limitation, the present finding adds to the literature documenting differential motivational responses in ASD to social sources of information (Chevallier et al., 2012; Dichter & Adolphs, 2012) by examining an ERP component of motivational responses. Additionally, results are consistent with prior findings that certain types of nonsocial stimuli may be highly salient for individuals with ASD (Klin et al., 2003; Klin et al., 2002). This “nonsocial bias” may be mechanistically related to the development of RIs in ASD and may interfere with social development (Cascio et al., 2014; Klin et al., 2007; Turner-Brown et al., 2011). It may be the case that intensive behavioral interventions for children with ASD should expand their focus from increasing the salience and reward value of social interactions to also targeting the effects of RIs in ASD on social communicative skills (Boyd, Conroy, Mancil, Nakao, & Alter, 2007). To the extent that brain systems processing motivational responses may be co-opted in ASD to be responsive to certain nonsocial stimuli rather than to social stimuli, optimal treatment outcomes may not be achievable until ASD interventions focus on reducing the motivational relevance of RIs.

Consistent with this idea, many early intervention programs for children with or at-risk for ASD teach parents to “follow the child's lead” as a strategy for encouraging the child's development in a variety of domains, including social-communication skills. “Following the child's lead” involves observing the child's behavior, recognizing the child's interests, and joining in the child's activities, rather than redirecting the child. Thus, if a child is demonstrating an RI, the therapist would attempt to engage the child in a social-communication interaction using that RI. Subsequent portions of the intervention may then include increasing the child's interest in their play-partner than the RI (Mahoney & MacDonald, 2007). This type of intervention has demonstrated positive parent and child outcomes, including in the context of Responsive Teaching (Karaaslan, Diken, & Mahoney, 2013; Mahoney & MacDonald, 2007; Mahoney & Perales, 2005), Adapted Responsive Teaching (Baranek et al., 2015); Focused Playtime Intervention (Kasari, 2014; Siller, Hutman, & Sigman, 2013; Siller, Swanson, Gerber, Hutman, & Sigman, 2014), and Hanen's More Than Words program (Carter et al., 2011; Venker, McDuffie, Ellis Weismer, & Abbeduto, 2012). The results of the current study support the potential utility of behavioral ASD interventions to leverage nonsocial interests to improve social-communication functioning in children with ASD by gradually expanding the child's interests to include new objects, actions, and people.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the families who participated in this study. This research was supported by MH081285, MH073402, HD079124, and the UNC-CH Graduate School Dissertation Completion Fellowship (CRD).

References

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V. 5th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Attwood T. Understanding and managing circumscribed interests. In: Prior M, editor. Learning and behavior problems in Asperger syndrome. Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 126–147. [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, Watson LR, Turner-Brown L, Field SH, Crais ER, Wakeford L, et al. Reznick JS. Preliminary Efficacy of Adapted Responsive Teaching for Infants at Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in a Community Sample. Autism Research and Treatment. 2015;2015:16. doi: 10.1155/2015/386951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer M, Schacht A. Event-related brain responses to emotional words, pictures, and faces - a cross-domain comparison. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodfish J, Symons F, Lewis M. The Repetitive Behavior Scale: Test Manual. Morganton, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd BA, Conroy MA, Mancil GR, Nakao T, Alter PJ. Effects of circumscribed interests on the social behaviors of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(8):1550–1561. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Messinger DS, Stone WL, Celimli S, Nahmias AS, Yoder P. A randomized controlled trial of Hanen's ‘More Than Words’ in toddlers with early autism symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(7):741–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio CJ, Foss-Feig JH, Heacock J, Schauder KB, Loring WA, Rogers BP, et al. Bolton S. Affective neural response to restricted interests in autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):162–171. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(4):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007. doi:S1364-6613(12)00052-6 [pii] 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron FM. Neural correlates of written emotion word processing: a review of recent electrophysiological and hemodynamic neuroimaging studies. Brain and Language. 2012;122(3):211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP. The Social Responsiveness Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cox A, Kohls G, Naples AJ, Mukerji CE, Coffman MC, Rutherford HJ, et al. McPartland JC. Diminished social reward anticipation in the broad autism phenotype as revealed by event-related brain potentials. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2015 doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Schupp HT, Bradley MM, Birbaumer N, Lang PJ. Brain potentials in affective picture processing: covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report. Biological Psychology. 2000;52(2):95–111. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cygan HB, Tacikowski P, Ostaszewski P, Chojnicka I, Nowicka A. Neural correlates of own name and own face detection in autism spectrum disorder. Plos One. 2014;9(1):e86020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton KM, Holsen L, Abbeduto L, Davidson RJ. Brain function and gaze fixation during facial-emotion processing in fragile X and autism. Autism Res. 2008;1(4):231–239. doi: 10.1002/aur.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Meltzoff AN, Osterling J, Rinaldi J, Brown E. Children with autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. J Autism Dev Disord. 1998;28(6):479–485. doi: 10.1023/a:1026043926488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Webb SJ, McPartland J. Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;27(3):403–424. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2703_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmonte S, Balsters JH, McGrath J, Fitzgerald J, Brennan S, Fagan AJ, Gallagher L. Social and monetary reward processing in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2012;3(1):7. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devitt NM, Gallagher L, Reilly RB. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Fragile X Syndrome (FXS): Two Overlapping Disorders Reviewed through Electroencephalography-What Can be Interpreted from the Available Information? Brain Sci. 2015;5(2):92–117. doi: 10.3390/brainsci5020092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Adolphs R. Reward processing in autism: a thematic series. J Neurodev Disord. 2012;4(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Benning SD, Holtzclaw TN, Bodfish JW. Affective modulation of the startle eyeblink and postauricular reflexes in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(7):858–869. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0925-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Felder JN, Green SR, Rittenberg AM, Sasson NJ, Bodfish JW. Reward circuitry function in autism spectrum disorders. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;7(2):160–172. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Tomarken AJ, Baucom BR. Startle modulation before, during and after exposure to emotional stimuli. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2002;43(2):191–196. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(01)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth H, Angrilli A, Calogero A, Harper J, Olson LA, Bernat E. Reduced negative affect respose in female psychopaths. Biological Psychology. 2013;94:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.07.007. doi:10.1016/j.bipsycho.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischler I, Bradley M. Event-related potential studies of language and emotion: words, phrases, and task effects. Prog Brain Res. 2006;156:185–203. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(5):693–705. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunji A, Inagaki M, Inoue Y, Takeshima Y, Kaga M. Event-related potentials of self-face recognition in children with pervasive developmental disorders. Brain Dev. 2009;31(2):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert C, Junghofer M, Kissler J. Event related potentials to emotional adjectives during reading. Psychophysiology. 2008;45(3):487–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert C, Kissler J, Junghofer M, Peyk P, Rockstroh B. Processing of emotional adjectives: Evidence from startle EMG and ERPs. Psychophysiology. 2006;43(2):197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heritage AJ, Benning SD. Impulsivity and response modulation deficits in psychopathy: evidence from the ERN and N1. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(1):215–222. doi: 10.1037/a0030039. doi:2012-25386-001 [pii] 10.1037/a0030039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hus V, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4: Revised Algorithm and Standardized Severity Scores. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper HH. The 10-20-electrode system of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1958;10:370–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaaslan O, Diken IH, Mahoney G. A Randomized Control Study of Responsive Teaching With Young Turkish Children and Their Mothers. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2013;33(1):18–27. doi: 10.1177/0271121411429749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari CC. Randomized controlled trial of parental responsiveness intervention for toddlers at high risk for autism. Infant behavior & development. 2014;37(4):711. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test: KBIT. AGS, American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Bradley MM, Hauk O, Rockstroh B, Elbert T, Lang PJ. Large-scale neural correlates of affective picture processing. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(5):641–649. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394162. doi:10.1017.S0048577202394162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Danovitch JH, Merz AB, Volkmar FR. Circumscribed interests in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: An exploratory study. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2007;32(2):89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, Volkmar F. The enactive mind, or from actions to cognition: lessons from autism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358(1430):345–360. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, Volkmar F, Cohen D. Defining and quantifying the social phenotype in autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):895–908. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Lin DJ, Gorrindo P, Ramsay G, Jones W. Two-year-olds with autism orient to non-social contingencies rather than biological motion. Nature. 2009;459(7244):257–261. doi: 10.1038/nature07868. doi:nature07868 [pii] 10.1038/nature07868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls G, Chevallier C, Troiani V, Schultz RT. Social ‘wanting’ dysfunction in autism: neurobiological underpinnings and treatment implications. J Neurodev Disord. 2012;4(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-4-10. doi:1866-1955-4-10 [pii] 10.1186/1866-1955-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KS, Bodfish JW, Piven J. Evidence for three subtypes of repetitive behavior in autism that differ in familiality and association with other symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(11):1193–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SE, Mandell DS, Schultz RT. Autism. Lancet. 2009;374(9701):1627–1638. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61376-3. doi:S0140-6736(09)61376-3 [pii] 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61376-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. Rutter M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louwerse A, Tulen JH, van der Geest JN, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, Greaves-Lord K. Autonomic responses to social and nonsocial pictures in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2014;7(1):17–27. doi: 10.1002/aur.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckhardt C, Jarczok TA, Bender S. Elucidating the neurophysiological underpinnings of autism spectrum disorder: new developments. J Neural Transm. 2014;121(9):1129–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, MacDonald J. Autism and Developmental Delays in Young Children: The Responsive Teaching Curriculum for Parents and Professionals Manual. Austin, Texas: PRO-ED, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, Perales F. Relationship-focused early intervention with children with pervasive developmental disorders and other disabilities: a comparative study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(2):77–85. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPartland JC, Wu J, Bailey CA, Mayes LC, Schultz RT, Klin A. Atypical neural specialization for social percepts in autism spectrum disorder. Soc Neurosci. 2011;6(5-6):436–451. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.586880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan A, Richardson T, Anney RJ, Gill M. The Social Communication Questionnaire in a sample of the general population of school-going children. Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178(2):193–199. doi: 10.1007/s11845-008-0184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadig A, Lee I, Singh L, Bosshart K, Ozonoff S. How does the topic of conversation affect verbal exchange and eye gaze? A comparison between typical development and high-functioning autism. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(9):2730–2739. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.05.020. doi:S0028-3932(10)00201-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Iosif AM, Baguio F, Cook IC, Hill MM, Hutman T, et al. Young GS. A prospective study of the emergence of early behavioral signs of autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(3):256–266 e251. doi:00004583-201003000-00009 [pii] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson NJ, Dichter GS, Bodfish JW. Affective responses by adults with autism are reduced to social images but elevated to images related to circumscribed interests. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson NJ, Elison JT, Turner-Brown LM, Dichter GS, Bodfish JW. Brief Report: Circumscribed Attention in Young Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(2):242–247. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson NJ, Touchstone EW. Visual attention to competing social and object images by preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(3):584–592. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1910-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacht A, Sommer W. Emotions in word and face processing: early and late cortical responses. Brain Cogn. 2009;69(3):538–550. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp HT, Stockburger J, Codispoti M, Junghofer M, Weike AI, Hamm AO. Selective visual attention to emotion. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(5):1082–1089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3223-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Dapretto M, Ghahremani DG, Poldrack RA, Bookheimer SY. Reward processing in autism. Autism Res. 2010;3(2):53–67. doi: 10.1002/aur.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller, Hutman T, Sigman M. A parent-mediated intervention to increase responsive parental behaviors and child communication in children with ASD: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(3):540–555. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1584-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller, Swanson M, Gerber A, Hutman T, Sigman M. A Parent-Mediated Intervention That Targets Responsive Parental Behaviors Increases Attachment Behaviors in Children with ASD: Results from a Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(7):1720–1732. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2049-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society AE. Guideline thirteen: guidelines for standard electrode position nomenclature. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;11(1):111–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South M, Ozonoff S, McMahon WM. Repetitive behavior profiles in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35(2):145–158. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-1992-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka JW, Leon AC, McCarry T, Nurse M, Hare TA, et al. Nelson C. The NimStim set of facial expressions: judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168(3):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Brown LM, Lam KS, Holtzclaw TN, Dichter GS, Bodfish JW. Phenomenology and measurement of circumscribed interests in autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2011;15(4):437–456. doi: 10.1177/1362361310386507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venker CE, McDuffie A, Ellis Weismer S, Abbeduto L. Increasing verbal responsiveness in parents of children with autism:a pilot study. Autism. 2012;16(6):568–585. doi: 10.1177/1362361311413396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vismara LA, Lyons G. Using perservative interests to elicit joint attention behaviors in young children with autism: Theoretical and clinical implications for understanding motivation. J Posit Behav Interv. 2007:214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Watson KK, Miller S, Hannah E, Kovac M, Damiano CR, Sabatino-DiCrisco A, et al. Dichter GS. Increased reward value of non-social stimuli in children and adolescents with autism. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1026. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SJ, Merkle K, Murias M, Richards T, Aylward E, Dawson G. ERP responses differentiate inverted but not upright face processing in adults with ASD. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;7(5):578–587. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Ferri J, Hajcak G. Interactions between attention and emotion. In: Robinson MD, Watkins ER, Harmon-Jones E, editors. Handbook of cognition and emotion. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya N, Kasari C, Sigman M, Mundy P. Facial expressions of affect in autistic, mentally retarded and normal children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1989;30(5):725–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]