Abstract

Research in developmental psychopathology and clinical staging models has increasingly sought to identify trans-diagnostic biomarkers or neurocognitive deficits that may play a role in the onset and trajectory of mental disorders and could represent modifiable treatment targets. Less attention has been directed at the potential role of cognitive-emotional regulation processes such as ruminative response style. Maladaptive rumination (toxic brooding) is a known mediator of the association between gender and internalizing disorders in adolescents and is increased in individuals with a history of early adversity. Furthermore, rumination shows moderate levels of genetic heritability and is linked to abnormalities in neural networks associated with emotional regulation and executive functioning. This review explores the potential role of rumination in exacerbating the symptoms of alcohol and substance misuse, and bipolar and psychotic disorders during the peak age range for illness onset. Evidence shows that rumination not only amplifies levels of distress and suicidal ideation, but also extends physiological responses to stress, which may partly explain the high prevalence of physical and mental co-morbidity in youth presenting to mental health services. In summary, the normative developmental trajectory of rumination and its role in the evolution of mental disorders and physical illness demonstrates that rumination presents a detectable, modifiable trans-diagnostic risk factor in youth.

Key words: Brooding, clinical staging, mental disorders, rumination, trans-diagnostic, youth

Introduction

Developmental psychopathology explores illness trajectories from a life-course perspective, and as such it may be especially helpful for understanding the emergence of mental disorders in youth (Scott et al. 2013). In young people, a particular challenge is to identify deviations in basic psychological and/or biological processes that can explain why the initial clinical presentation may demonstrate concurrent mental, physical, and alcohol/substance misuse disorders and/or the longitudinal phenomenology may show heterotypic continuity over time (McGorry et al. 2006; Hickie et al. 2013; Scott et al. 2013).

Attempts to understand evolving patterns of signs and symptoms have increasingly focused on the application of dimensional approaches such as clinical staging and the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative (Insel et al. 2010; Sanislow et al. 2010; Hickie et al. 2013; McGorry et al. 2014). Both approaches highlight the need to consider psychopathology on a continuum (from normal experiences through to established clinical disorders) and emphasize that our understanding of liability and co-morbidity is more likely to be improved by examining putative underlying mechanisms that cut across current heterogeneous disorder categories (Baskin-Sommers & Foti, 2015). Implicit in these frameworks is the notion that identifying trans-diagnostic processes that translate into ‘modifiable factors’ is a critical step in the development of precision or personalized medicine for mental disorders (Insel et al. 2010; McGorry et al. 2014), and moreover, that clinical advances will only really be achieved by greater integration of behavioural neuroscience into the study of psychopathology (Sanislow et al. 2010). However, research to date has predominantly focused on ‘biomarkers’ (measurable biological characteristics) and/or neurocognition (‘cold circuits’) (McGorry et al. 2014). There have been fewer reviews that synthesize data on ‘hot cognitions’ (Simon et al. 2015), such as cognitive processing styles involved in emotional regulation.

Given the lack of reviews that focus on cognitive-emotional processes that may act as a trans-diagnostic risk factor in young people with emerging severe mental disorders, we explore whether a particular ‘coping style’, namely rumination (and particularly ‘toxic’ brooding), can be considered as a specific age- and stage-related mechanism for psychopathology in youth. Whilst rumination has been studied extensively, we particularly focus on its evolution and its role in shaping emotional responses to stress in childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, including the peak age of onset period for psychosis, mood disorders and alcohol/substance misuse (between the ages of about 15 and 25 years) (Kessler et al. 2005; Jones, 2013) and whether rumination is a mechanism that can also help explain why many disorders in young people show heterotypic continuity over time and related phenomena such as multi-finality and pluri-potentiality (Ehring & Watkins, 2008).

The paper begins by briefly discussing cognitive-emotional regulation and the concept of coping response style, and then reviews rumination from the perspective of theories about its evolution, its normal developmental trajectory and its role in the evolution of high prevalence disorders (such as anxiety and depression) that are often the early stage clinical phenotypes that co-occur with severe mental disorders in adolescence and early adulthood. Next, the paper explores the emerging evidence for links between rumination and alcohol and substance misuse, and bipolar and psychotic disorders. Finally, we briefly highlight the neurobiological underpinnings of rumination and how its putative role in physiological responses to stress may offer insights into the high prevalence of physical and mental co-morbidities in young people.

Brief overview of cognitive-emotional regulation and rumination

Cognitive-emotional regulation (CER) encompasses any attempt to understand and shape the emotions experienced and how these are expressed (Gross & Munoz, 1995). This regulation can be implicit (automatic, unconscious) or explicit (deliberate, requiring conscious effort) (Gyurak et al. 2011). Conscious, effortful cognitive processes can be adaptive or maladaptive and include strategies such as reappraisal and rumination (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2007).

The most widely researched example of CER is the Response Styles Theory (RST; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987). RST focuses on individual styles of processing emotion that emerge in reaction to stressors and identifies four main coping responses: distraction, problem solving, risk taking, and rumination (see Table 1). Problem solving and distraction are considered to be adaptive response styles as they can positively impact on outcomes and provide opportunities for positive reinforcement, which increases future positive emotions and decreases negative affect (Abela et al. 2007). Risk-taking is considered maladaptive as, although it may temporarily offer distraction from or avoidance of difficult situations or feelings, the ‘downstream’ effects are more often negative (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008).

Table 1.

Key elements of cognitive emotion regulation and response styles theory

| Cognitive emotional regulation (Gross & Munoz, 1995; Gyurak et al. 2011) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion regulation | Process | Examples | |

| Explicit | Deliberate and conscious, and demands some level of monitoring during implementation. It is performed with insight and awareness | A situation is selected, modified, attended to, and appraised to yield a certain set of emotional responses. This is conducted in accordance with immediate and long term goals |

|

| Implicit | Automatic and unconscious, and thus requires little effort. It is performed without monitoring, insight, or comprehension | Like explicit emotion regulation, a situation is selected, modified, attended to, and appraised to produce a set of emotional responses. However this is done without cognitive engagement in the emotion regulation process |

|

Rumination can be viewed as a stable individual trait (Smith & Alloy, 2009) characterized by ‘the tendency to repetitively analyse one's problems, concerns and feelings of distress without taking actions to make positive changes’ (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991, p. 569). Rumination appears to be a multifaceted construct, having adaptive and maladaptive components, often referred to as ‘reflective pondering’ and ‘toxic brooding’, respectively (Treynor et al. 2003). Treynor et al. (2003) define reflection as a purposeful turning inward to engage in cognitive problem solving to alleviate one's distress whilst brooding is defined as ‘passive comparison of one's current situation with some unachieved standard. Brooding is associated with the maintenance and exacerbation of negative mood states such as depression and dysphoria (Verhaeghan et al. 2014), and negative cognitive biases such as attentional engagement with negatively valanced stimuli (Joormann, 2004).

Several models of rumination confirm that it acts to amplify and prolong a prevailing mood state (see Smith & Alloy, 2009), increasing the likelihood that dysphoria will progress to depression, and can increase anxiety in individuals faced with threatening situations (Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). Negative cycles of rumination and dysphoria make it increasingly likely that an individual will focus on prior negative thoughts and experiences, which further impairs instrumental behaviour and effective problem solving (Brosschot et al. 2006; Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). In contrast, there is emerging evidence that positive self-focused attention (positive reflection or ‘basking’) can be associated with lower levels of anxiety or negative affect (Segerstrom et al. 2003; Feldman et al. 2008; Raes et al. 2012; Hou & Ng, 2014).

How ruminative thought processes, such as toxic brooding, emerge and the underpinning mechanisms have been addressed by several research groups. The most prominent models of rumination, like RST, propose that rumination emerges in reaction to emotions such as negative affect and sadness, and that it is the styles of processing and reacting to emotions that lead to adverse psychological and physical health consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Conway et al. 2000). Other models, such as the ‘goal progress theory’ or ‘goal conflict theory’ propose that rumination is a response to behavioural inhibition and failure to progress satisfactorily towards a goal, or inaction and increased negative cognitive rehearsal associated with conflictual strivings, rather than a reaction to mood state per se (Emmons & King, 1988; Martin et al. 1993). It is suggested that failure to progress toward a goal and act on competing desires inaugurate ruminative thinking, which then leads to aversive psychological consequences such as mental disorders (Jones et al. 2009; Einstein, 2014). There is evidence that individuals who fail to progress toward goal states have lower wellbeing (Emmons & King, 1988), that high levels of goal failure combined with maladaptive rumination (brooding) are associated with more depressive symptoms (Jones et al. 2009), and that rumination mediates the link between goal attainment and positive affect (McIntosh et al. 1995).

Intolerance of uncertainty (IU), defined as a cognitive bias that affects how a person interprets and responds to uncertain situations (Dugas et al. 2004) is another mechanism proposed to underpin ruminative thinking (de Jong-Meyeret al. 2009; Yook et al. 2010; Einstein, 2014). It is suggested that individuals with IU are more sensitive to stress and use maladaptive coping strategies, such as dysfunctional cognitive processes or safety behaviours such as rumination, in order to reduce uncertainty, which may amplify affective states (McIntosh & Martin, 1992). Studies of IU and rumination demonstrate that rumination completely mediates the relationship between IU and depression (Yook et al. 2010; Liao & Wei, 2011), but other cognitive biases such as worry did not show a mediation effect (Yook et al. 2010).

Developmental trajectory of rumination

This section briefly examines evidence for the development of rumination over the life span, selecting three key topics to discuss: age, gender and early environment (including exposure to adversity).

Age and gender

Rumination involves a process of cognitive appraisal and so requires some capacity for basic abstract thinking and formal operational thought, which usually become apparent during the transition from mid-childhood to early adolescence (Piaget, 1977; Cole et al. 2006). Population-based studies confirm that children and pre-adolescents show significantly lower levels of rumination than adolescents (Hampel & Petermann, 2005; Thompson et al. 2010). Interestingly, Sütterlin et al. (2012) showed a decline in rumination from early adulthood onwards, where the highest levels of ‘brooding’ occurred in individuals aged <25 years. Explanations of the age trajectory of rumination concentrate on the potential long-term impact of childhood coping skills development and experiences. For example, some investigators have suggested that a peak in toxic brooding during adolescence is linked to difficulties in coping with increased levels of normative stressors that occur in this age range especially in those who failed to acquire sufficient adaptive problem-solving skills at an earlier age (Compas, 1987).

Gender differences in rumination also emerge during adolescence, with levels increasing in a linear fashion for girls from 12 to 15 years of age onwards, but with limited increases in rumination in males during the post-pubertal period (Tamres Janicki & Helgeson, 2002; Jose & Ratcliffe, 2004; Jose & Brown, 2008). There are a number of theories as to why females may ruminate more than males, including gender-stereotyped coping style (Cox et al. 2010) and differences in self-perceptions of emotionality and the stressfulness of the environment (Rudolph & Hammen, 1999; Gohm, 2003; Hyde et al. 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012). Against the latter, a meta-analysis by Tamres et al. (2002) found that gender differences in rumination were independent of the appraisal of stressors. Interestingly, work on ‘pubertal timing’ suggests that early puberty predicted higher levels of interpersonal dependent events and enhanced the risk of dysphoric symptoms in boys and girls who had a more negative cognitive style and a lower level of emotional clarity (Hamilton et al. 2014a, b).

Early environment

Some research indicates that future risk of becoming a ‘ruminator’ may be associated with early adversity, and rumination can be a learnt response style developed via parent modelling and communication (Hankin et al. 2009; Cox et al. 2010). Nolen-Hoeksema (1998) proposed that children who have little perceived control over their environment might be especially prone to becoming ruminators in adolescence. For example, pre-school exposure to ‘negative-submissive family expressivity’ has been shown to predict rumination in adolescence (Hilt et al. 2012), whilst exposure to ‘over-controlling’ parenting can undermine the child's sense of self-efficacy or mastery and contribute to the development of maladaptive coping strategies (Parker, 1983; Blatt & Homann, 1992) and a greater tendency to ruminate (Spasojevic & Alloy, 2002; Manfredi et al. 2011).

Neglect or abuse in childhood may shape a child's response to their environment, e.g. being vigilant to signs of threat and becoming passive to avoid aggravation in such situations, paying greater attention to negative stimuli, etc. (Macleod et al. 2002). In such circumstances, a child who feels helpless and socially and emotionally isolated may show reduced reliance on externally-oriented problem solving and an increased likelihood of engaging in solitary coping styles such as rumination (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1994). Moreover, Pearson et al. suggested that childhood abuse increases the development of anxious attachments, which have been found to prospectively predict rumination (Pearson et al. 2011).

Several studies offer support for the association between early adversity and rumination. For example, in non-clinical samples of college students, individuals with a history of childhood sexual abuse showed higher levels of rumination about sadness and dysphoria than those without such a history (Conway et al. 2004). Likewise, clinical studies confirm an association between childhood sexual and emotional abuse and adult ruminative response style (e.g. Spasojevic & Alloy, 2002); however, trends were statistically significant for females but not males (although the latter might be due to limited statistical power). A recent study by O'Mahen et al. (2015) examined different experiences of childhood maltreatment in depressed and non-depressed pregnant women and suggested that childhood emotional neglect was related to behavioural avoidance whilst childhood emotional abuse was associated with rumination. Importantly, repeated assessment of nearly 1000 adolescents demonstrated that emotional abuse by parents or peers was an antecedent of negative coping and cognitive styles, and, as elaborated below, brooding mediated the association between abuse and future depressive symptoms (Padilla & Calvete, 2014).

It is important to note that all these adverse experiences may be linked by an overarching issue, namely that they reduce the capacity of a child or adolescent to engage in effective and balanced control of their multiple needs; this in turn may exacerbate feelings of hopelessness, especially if they are living in unsupportive environments (Mansell & Carey, 2013). Furthermore, these elements may increase the long-term risk of developing psychological problems and mental disorders in the future (Powers, 1973).

Rumination and psychopathology

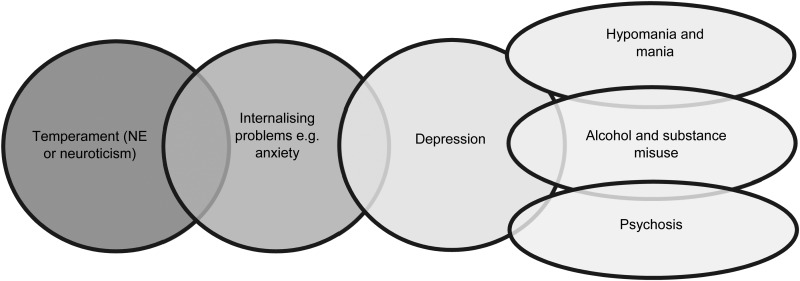

The increased interest in early intervention in youth with severe mental disorders has led to greater awareness of illness trajectories, in particular that preschool temperament or personality traits can be risk markers for psychopathology such as internalizing or anxiety problems in childhood, which may precede the onset of depressive symptoms or disorders and be the antecedents of later psychopathology (see Fig. 1). Not all individuals show progression from high prevalence disorders (e.g. anxiety, depression) to the lower prevalence disorders (e.g. psychosis, bipolar disorders), which is a developmental pattern that mimics a clinical staging model (McGorry et al. 2006). Clinical staging involves a detailed assessment of where an individual exists on a continuum of disorder progression from stage 0 (an at-risk but asymptomatic state) through to stage IV (late or end-stage disease) (McGorry et al. 2006; Hickie et al. 2013; McGorry et al. 2014), and it is used routinely to describe disease progression in general medicine, e.g. for heart disease or diabetes. If this is a plausible approach for mental disorders, then trans-diagnostic mechanisms should be identifiable across stages and over time both within and between individuals.

Fig. 1.

Representation of clinical stages of mental disorders beginning with early childhood temperament through to anxiety, depression, and then severe mental disorders (with peak age of onset in late adolescence/early adulthood).

Temperament, rumination and future psychopathology

Temperament can be broadly defined as biologically based, relatively stable individual differences in emotions, behaviours, and cognitions (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Negative emotionality (NE) is an infant temperamental style that is widely associated with psychopathology in adolescence, with high NE individuals experiencing negative emotions more frequently and intensely than their peers (Belsky et al. 1996), and are more likely to exhibit depression (Mezulis et al. 2011), anxiety (Hudson & Rapee, 2004), and/or substance abuse (Allen & Gabbay, 2013).

A prospective longitudinal study from birth to adolescence, found that rumination significantly mediated the association between NE in infancy and depressive symptoms at age 15 years (Mezulis et al. 2011). Consistent with other studies (e.g. Verstraeten et al. 2009), Mezulis et al. (2011) noted that the association was stronger among adolescent girls, although a further study by the same group highlighted that high levels of depressive symptoms at age 11 were associated with both early puberty and high levels of NE in boys (Mezulis et al. 2014).

Neuroticism is a similar but narrower construct than NE (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985). Like NE, ruminative response style has been shown to fully or partially mediate the association between neuroticism and anxiety and depression in adolescents and young adults (Muris et al. 2005; Kuyken et al. 2006; Roelofs et al. 2008).

Anxiety and depression

About 50% of individuals with anxiety disorders experience their first symptoms by the age of 11 (Kessler et al. 2005). A number of studies demonstrate that childhood anxiety and/or internalizing symptoms may predict adolescent depressive symptoms/episodes (Last et al. 1997; Horn & Wuyek, 2010), whilst anxiety disorders in early adolescence significantly predict first onset of a major depressive episode (MDE; Bittner et al. 2004). Rates of depressive disorders increase markedly during mid to late adolescence with about 20% of adolescents experiencing a MDE (Lewinsohn et al. 1998), and concurrent depression and anxiety occurs significantly more frequently in adolescence compared to childhood (Lamers et al. 2011).

Studies suggest that there is a robust relationship between rumination and the development of internalizing problems (such as withdrawal, anxiety and depression) but not externalizing problems (such as aggression, hyperactivity, etc.) in childhood (Garnefski et al. 2005). Rumination is also significantly associated with the development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms in adolescents (e.g. Garnefski et al. 2001, 2002; Tan et al. 2012; Jose et al. 2012; Jose & Weir, 2013), and increases the risk of developing anxiety problems in early adolescence (Tan et al. 2012). Furthermore, in a mid-teen sample, social anxiety (a recognized antecedent of severe mental disorders) directly predicted higher levels of rumination over time, especially in females (Jose et al. 2012).

Stressful life events and experiences such as bullying are potent risk factors for the development of internalizing symptoms (e.g. McLaughlin et al. 2009). In cross-sectional and prospective studies, McLaughlin and colleagues (e.g. McLaughlin & Hatzenbuehler, 2009; McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012) demonstrated that rumination fully mediated the relationship between stressful life events and anxiety and depression among adolescents, but only partially mediated the association in adults. A large-scale study by Michl et al. (2013) confirmed that rumination is a key mediator between stress and anxiety and depressive phenomena in adolescents.

Independently for depression, there is a vast literature that indicates that rumination is significantly associated with depression onset, maintenance, and relapse, especially during adolescence (e.g. Wood et al. 1990; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Michalak et al. 2012). A meta-analysis demonstrated that the higher levels of rumination in females compared to males significantly mediated the increased rates of depression that becomes apparent post-puberty (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012). Broderick (1998) suggests that adolescents use rumination to deal with family, academic, and peer group problems, which become increasingly more stressful and prominent during the adolescent period. However, as ruminative response style exacerbates rather than reduces the negative outcomes of stressful life events, it increases the likelihood of depressive outcomes (Schwartz & Koenig, 1996; Broderick, 1998; Kraaij et al. 2003). Furthermore, a study of an ethnically diverse sample of over 1000 college students demonstrated that individuals who brood in response to negative life events may be vulnerable to thinking about suicide, and that whilst level of suicidal ideation was partly explained by severity of symptoms of depression, it was also directly related to brooding itself (Chan et al. 2009).

Alcohol and substance misuse

The prevalence of alcohol use disorders (AUD) and substance use disorders (SUD) in adolescents range from about 5–10% (Merikangas et al. 2010; Merikangas & McClair, 2012). Approximately 40% of individuals with an AUD and just below 50% of those with SUD experienced their first symptoms of harmful use before 19 years (Helzer et al. 1991; Dennis et al. 2002).

In clinical settings, 70–80% of adolescents with AUD and SUD have a co-morbid mental disorder (Ḳaminer & Bukstein, 2008), including anxiety, depression, psychosis or bipolar disorders. Studies indicate that rumination increases the risk for harmful alcohol and/or substance use (e.g. Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002; Caselli et al. 2008; Caselli et al. 2010), particularly in female adolescents where rumination predicted the onset of substance abuse (and of bulimia), and predicted a future increase in substance abuse symptoms over a 4-year period (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2007).

The association between rumination and alcohol and substance misuse may be direct or indirect. For example, some studies of adolescents suggest that depression increases rumination, which in turn leads to increased substance use, as demonstrated by the association between brooding and marijuana use (Adrian et al. 2014). Skitch & Abela (2008) showed that ruminative brooding predicted substance abuse for up to 18 weeks following negative events, and that this effect was exacerbated in older adolescents with an existing MDE. Other research supports a direct association (e.g. Willem et al. 2011), reporting that, independent of depression, adolescents with lower reflective pondering demonstrated higher drug consumption whilst higher brooding was associated with more problematic substance use.

Bipolar disorders (BD)

The peak age of onset for BD is late adolescence and early adulthood, although most individuals experience one or more MDE, brief hypomania or sub-threshold mania before syndromal episodes of hypomania or mania occur (Duffy et al. 2009; Douglas & Scott, 2014). Those individuals with depression who may be at highest risk of transition to BD often show cyclothymic or hypomanic personality traits or have a family history of bipolar disorders (Duffy et al. 2009; Geoffroy et al. 2013; Bechdolf et al. 2014).

There is limited research on rumination and mania in adolescents and young adults, but studies in middle-aged adults or mixed samples of younger and older adults show that rumination is present in both the depressed and (hypo)manic phases of BD, is increased in unaffected first degree relatives compared to healthy controls, and that increased rumination predicts relapse and/or worse course of illness (Johnson et al. 2008; Van der Gucht et al. 2009; Green et al. 2011; Ghaznavi & Deckersbach, 2012).

A study of university students (mean age 22 years) (Thomas & Bentall, 2002), reported that ruminative response style was positively correlated with scores on the Hypomanic Personality Scale (Eckblad & Chapman, 1986). A second study of undergraduate students (mean age 19 years) by the same group found that rumination was independently associated with both depression and hypomania symptom scores (Knowles et al. 2005), and that risk-taking behaviours were also increased in association with rumination, especially in males. Knowles et al. (2005) hypothesized that rumination may exacerbate depressive symptoms whilst some individuals make active attempts to avoid negative or intense mood states by engaging in high-risk activities, which may be linked to hypomanic or manic symptoms (Van der Gucht et al. 2009; Weiss et al. 2015).

Studies of individuals at high risk of BD or the offspring of BD parents demonstrate early evidence of deficits in CER (e.g. Nijjar et al. 2014; Van Rheene et al. 2015). In a study of response styles, Jones et al. (2006) found that offspring with current or past evidence of psychopathology (affected offspring) and unaffected offspring had higher levels of rumination than age- and gender-matched controls. Pavlickova et al. (2014) demonstrated that, compared to offspring of healthy parents, affected offspring of bipolar parents showed significantly increased levels of rumination and of hypomanic cognitions compared to unaffected offspring or healthy controls. An experiential sampling study by the same group examined the inter-relationships between mood, self-esteem and response styles over 6 days (Pavlickova et al. 2015). Interestingly, increased negative as well as positive mood resulted in greater rumination in offspring and controls, and low self-esteem triggered greater risk-taking in the bipolar offspring group, while negative affect instigated increased active coping in the control group. Additionally, as in studies of depression, CER impairments such as increased ruminative response style are associated with suicidal ideation in young people with emerging bipolar disorders (Stange et al. 2015).

Psychosis

The typical age of onset for psychotic disorders is late adolescence or early twenties, being slightly later in females than males (Hafner et al. 1994; Gogtay et al. 2011). Several studies report that anxiety or depression in childhood or adolescence may precede the onset of psychosis (Baynes et al. 2000; Mulholland & Cooper, 2000; Maggini & Raballo, 2006). Research in groups at high risk of psychosis indicate that transition is common in those who have experienced brief periods of psychosis or psychotic-like symptoms (Yung et al. 2006), whilst the presence of depression and/or anxiety is associated with increased suicidality, self-harm, disorganized behaviour, disorganized speech, and anhedonia (Fusar-Poli et al. 2014).

Rumination has been shown to be associated with hallucination-proneness and a range of mild anomalous experiences including feelings of unreality, perceptual alterations, and temporal disintegration (Jones & Fernyhough, 2009; Freeman et al. 2013). Experiential sampling in young adults with psychosis demonstrates that antecedent rumination and worry predict persecutory delusions and auditory hallucinations, and that rumination predicted the level of distress associated with these psychotic experiences (Hartley et al. 2014). Also, Halari et al. (2009) demonstrated that rumination can be associated with negative symptoms such as stereotyped thinking and emotional withdrawal.

As ruminative response style overlaps with perseverative thinking, it could indicate that rumination in psychosis is associated with underlying psychotic or dysphoric (anxiety/depressive) dimensions (Cernis et al. 2015). Theoretically, rumination might also help explain why some young people who experience psychotic symptoms become distressed and seek help, whilst others do not (Van Nierop et al. 2012; Rapado-Castro et al. 2015).

Lastly, in a cross-sectional study of psychotic inpatients with and without suicidality (n = 2383; mean age at onset 25 years), ruminative thinking, social withdrawal, and lack of activity were all associated with increased suicidality (Ahrens & Linden, 1996).

Neurobiological underpinnings of rumination

Neurobiological factors play a key role in the activation and maintenance of cognitive-emotional processes. This section briefly examines a selection of the developing research on the associations between rumination in young people and genetics, neuropsychology, physiology, sleep and physical health.

Genes

There are reasons to consider the role of genetics in the development of rumination. As noted, rumination may mediate the association between temperamental styles that are heritable (e.g. NE, neuroticism) and depression. Furthermore, children at high risk of depression (e.g. offspring of mothers with a history of MDE) show higher levels of rumination than controls (Gibb et al. 2012). A small number of twin studies have examined genetic and environmental influences (shared and non-shared elements) on rumination, brooding and mood disorders. In a Chinese study of adolescent twins, the heritability of depression (30–42%) was modest, but genetic effects accounted for 24% of the variation in adolescent rumination, and genetics mediated the relationship between rumination and depression (Chen & Li, 2013). In a US study of adolescent twins aged 12–14 years, heritability accounted for 21% of the variation in adolescent brooding, highlighting again that although the heritable influences were modest, they accounted for the majority of the relationship between brooding and depression (h2 = 0.62) (Moore et al. 2013). Preliminary data from a UK study of BD in twins and siblings showed that ruminative response style had a low to moderate heritability with 23% of the total variance accounted for by additive genetic effects (Beards et al. 2012).

Certain polymorphisms of the BDNF gene (a protein involved in the growth of new and existing neurons and synapses) have also been found to be linked to rumination (Beevers et al. 2009). Results suggest that individuals with the Val66Met BDNF gene polymorphism are significantly more likely to ruminate than individuals without the gene. This is consistent with recent research that has found an association between the BDNF gene Val66Met polymorphism, rumination, and depression (Hilt et al. 2007), where analyses suggested that rumination mediated the relationship between the BDNF polymorphism and depressive symptoms.

Neuropsychology

A number of cognitive processes are activated when engaging in rumination, in particular attention, memory, and self-referential processing (Lyubomirsky et al. 1998). Investigators have reported that rumination generates difficulties in controlling the entry of irrelevant information into working memory (WM) and short-term memory (STM) (Joormann, 2004; Goeleven et al. 2006; Joormann et al. 2010), or the removal of negative self-relevant information from WM and STM storage (Joormann & Gotlib, 2008). Ruminators also show general deficits in the ability to shift attention from unhelpful to helpful strategies (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Futhermore, a study of over 200 adolescents demonstrated that engaging in ruminative thoughts consumes cognitive resources that would otherwise be allocated towards difficult tests of executive functioning (the resource allocation hypothesis). In contrast, no evidence was found to support the notion that lower levels of executive functioning at baseline predicted levels of rumination or depressive symptoms at follow-up (Connolly et al. 2014).

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) shows that rumination is positively correlated with an increased activation of the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala (Ray et al. 2005), and adults who ruminate regularly (e.g. dysphoric or depressed patients) show high connectivity between these structures (Gotlib & Hamilton, 2008). Ruminators also engage in higher rates of self-referential processing compared to their non-ruminative counterparts (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010); a process that can be examined via neuroimaging of the default mode network (DMN) (Ochsner & Gross, 2005; Schmitz & Johnson, 2006). In non-ruminators, activation of DMN brain regions is reduced after performing non-self-referential (i.e. goal-directed) activities during off-task or rest periods, suggesting an ability to lose one's self in the work (Sheline et al. 2009). In contrast, high ruminators show high connectivity between DMN regions during these rest periods, reflecting an inability to suppress self-referential thoughts during off-task times. Berman et al. (2011b) noted that in young adults (mean age 22 years) these connectivities were only found when participants engaged in brooding and not reflective pondering.

Marchetti et al. (2012) propose that an imbalance in the task positive (TP) and task negative (TN) elements of the DMN is the overarching neural mechanism involved in rumination. Studies of rumination in youth (Berman et al. 2011a) and of adult depressed cases v. controls (Hamilton et al. 2011) support the proposal that a TN-TP imbalance is associated with a failure to attenuate TN activity in the transition from rest to task periods and with toxic brooding.

A recent fMRI study compared healthy controls with unmedicated adolescents in remission from MDE (Jacobs et al. 2014) and showed that the remitted MDE adolescents exhibited hyper-connectivities within the DMN and between the DMN and salience networks (posterior cingulate cortex, subgenual anterior cingulate, and amygdala) and regions of the cognitive control network, which were related to rumination and sustained attention. However, it was not possible to conclude that the hyper-connectivities represented brain-based markers of traits (e.g. rumination), as it is plausible that the hyper-connectivities represent compensatory mechanisms in individuals with emerging mood disorders. Fewer studies examine CER in individuals aged 15–25 years with emerging bipolar disorders, although in mixed samples of younger and older adults it has been shown that individuals at increased risk of developing bipolar disorders are less successful at down-regulating amygdala activity and demonstrate inefficient use of reappraisal and distraction strategies (e.g. Heissler et al. 2014).

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and physiological studies

Several physiological studies have examined the relationship between rumination and heart rate variability. Key et al. (2008) demonstrated that heart rate variability in response to stress is more strongly associated with trait rather than state rumination in female college students.

A review of the relationship between rumination and cortisol identified that 13 of 17 studies were undertaken in children, students or young adults (Zoccola & Dickerson, 2012). Whilst higher levels of state rumination were consistently linked to increased cortisol concentrations, findings were less consistent for the physiological effects of stressors (basal cortisol levels or cortisol awakening response to naturally occurring or laboratory-induced stress). However, those studies that utilized social-evaluative stressor tasks generally showed that rumination predicted greater cortisol reactivity or delayed recovery. These findings are supported by a study using pupillary response to perceived rejection in depressed adolescents (Stone et al. 2016).

Gianferante et al. (2014) also showed that rumination in response to repeated stress predicted non-habituation of the HPA axis, which the authors suggest may offer a pathway linking rumination to negative health outcomes. Interestingly, this association may be bidirectional or attenuated by baseline physical status (Puterman et al. 2011). For example, Puterman et al. (2011) demonstrated that although ruminators experienced a more rapid initial increase in cortisol levels, greater HPA axis reactivity, and slower HPA axis recovery from stress, this profile was only significant in sedentary participants. In active participants, cortisol trajectories were equivalent in high and low ruminators. These findings are noteworthy given the evidence of increased sedentary lifestyles and lower physical activity in youth with mental disorders (even when medication-free) compared to their peers (Gehue et al. 2015; Vallarino et al. 2015).

Sleep and circadian rhythms

Rumination may indirectly influence circadian rhythms through its association with increased cortisol production (Rea et al. 2010) and alterations in cortisol secretion patterns (for a review see Chan & Debono, 2010). Furthermore, studies of sleep in adolescents show rumination to be directly associated with poorer general sleep quality, longer time to fall asleep and more awakenings after sleep onset (Thomsen et al. 2003). Dysregulated sleep is associated with increased rumination compared to good sleepers with evidence that brooding is associated with fatigue, poor concentration and low mood (Carney et al. 2006). Zoccola et al. (2009) found that ruminating about a past stressor before bedtime predicted longer sleep onset latencies. This suggestion that post-stressor ruminative thought may predict delayed sleep onset is of particular interest as delayed sleep phase syndrome is a recognized marker of circadian disturbance that occurs more often in young compared to older adults (Robillard et al. 2014; Alloy et al. 2015; Steinan et al. 2015). Batterham et al. (2012) found that rumination and neuroticism mediated the relationship between self-reported sleep disturbance and new onset depressions in younger adults, but not the onset of generalized anxiety of panic disorders.

The above studies mainly relied on self-ratings rather than objective recordings of sleep. An exception is the study of university students (mean age about 20 years) by Pillai et al. (2014), which showed that nightly variations in pre-sleep rumination were predictive of significantly longer sleep onset latency (SOL) as recorded by actigraphy and by a self-report diary. It was estimated that, after controlling for baseline sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms, a one standard deviation increase on the pre-sleep rumination scale was associated with an approximately 7-min increase in actigraphy-based SOL.

Physical health and immune system

Rumination has been found to be negatively associated with self-reported physical health, including higher levels of somatic complaints and lower general health (Lok & Bishop, 1999; Rector & Roger, 1996). In a longitudinal study of younger compared to older adults, Thomsen et al. (2004a) demonstrated that higher levels of rumination predicted poorer self-reported physical health and more somatic complaints in those aged 20–35 years only. High levels of rumination have been linked with immune functioning, but to date these associations have only been reported for some of the immune markers measured (numbers of leucocytes, lymphocytes, and polyclonal activation), and the findings were significant in older but not younger adults (Thomsen et al. 2004b).

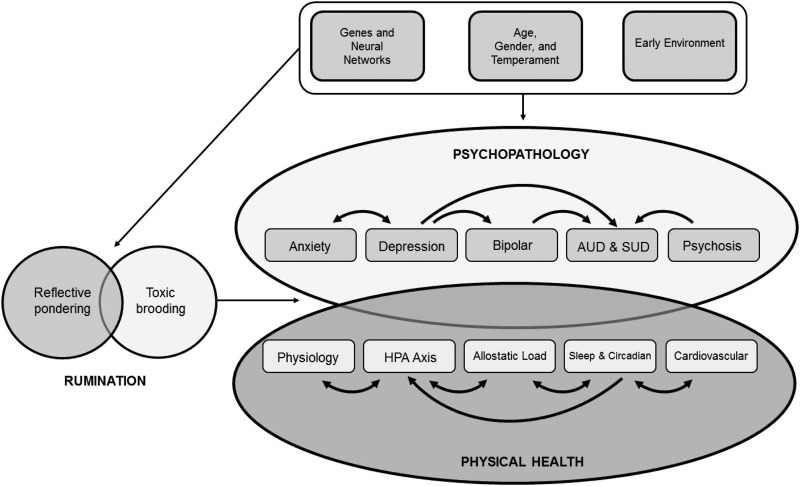

Brosschot (2010) suggests that sustained cognitive representations of events (namely rumination and worry) can cause prolonged physiological activity, which may lead to intermediate pathogenic states (such as increased allostatic load) and finally to somatic disease. Glynn et al. (2002) found that ruminating about an emotional task resulted in increased blood pressure and delayed blood pressure recovery, which parallel findings reported in students with high levels of rumination and in adults (Bermúdez & Perez-Garcia, 1996; Neumann et al. 2001). Finally, although the co-morbidity between mood disorders and cardiovascular disease reported in young adults may be linked to medications or lifestyle factors (Goldstein et al. 2015), it is hypothesized that trait rumination may delay physiological recovery from acute stress and could act as a mechanism (Larsen & Christenfeld, 2009) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Model of rumination as a trans-diagnostic process impacting psychopathology and physical health, underpinned by genes and neural networks, age, gender, and temperament, and early environment. AUD, Alcohol use disorder; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; SUD, substance use disorder.

Conclusions

This paper highlights several key aspects of rumination. First, we note that, of the two core components of rumination, it is the maladaptive (brooding) rather than the adaptive element (reflection or positive basking) that is consistently associated with the development of psychopathology. Also, the normative pattern of development of rumination parallels age and gender profiles associated with the typical evolution of internalizing disorders. Importantly, we highlight the association between the development of a ruminative response style and traumatic and abusive experiences in childhood, which are risk factors linked to a range of psychological problems in adolescence including mood and psychotic disorders. The evidence suggests that rumination is an underlying mechanism that contributes to a significant proportion of the explained variance between early adversity and later mental health problems. We do not claim that rumination is the only explanatory model, as other cognitive structures (e.g. beliefs and schemata) and processes have been implicated in the links between early trauma, CER and the development of psychopathology and acts of self-harm. Several studies demonstrate that these models and constructs may overlap and that there are links between early maladaptive schema, rumination and future symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents (Orue et al. 2014; Black & Pössel, 2015) or between early childhood trauma, over-general memory and high levels of ruminative thinking (Watkins & Teasdale, 2001; Williams et al. 2007). However, more research is needed to clarify the interactions between these different CER elements.

As reported in reviews of older adult populations, we confirm the importance of rumination in the evolution and maintenance of depression and highlight that in adolescence (but not always older adults) rumination may fully or partially mediate the relationship between childhood temperament and/or stressful events and the later onset of anxiety disorders. This sequence offers support for the notion of rumination being important in the longitudinal trajectory of the development of mental disorders and the notion that rumination plays a role in the transition between clinical stages. Our review differs from many previous reviews of rumination as a trans-diagnostic process operating across age groups and populations (Harvey et al. 2004; Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Watkins, 2009; Watkins & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2014), as we also examine the possible role of rumination in evolution of a problem from its sub-threshold phenomenology through to levels of harmful alcohol and substance use, bipolar and psychotic disorders that lead to help-seeking in an individual. Furthermore, we explore its putative influence on the trajectories of illness observed in this younger population and how similar processes may operate across physical and mental disorders. There is emerging evidence that rumination can be directly linked to the onset or maintenance of these problems in young adults, as well as existing evidence of indirect associations, with rumination exacerbating levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms, which in turn increase the distress that accompanies the symptoms or impede the ability to cope with those symptoms. It was also notable that rumination is frequently associated with suicidal ideation in depression, bipolar and psychotic disorders. We suggest that this is an important area for research, as the role of rumination in amplifying mood states and reducing flexibility in thinking styles and CER is under-explored in the age groups at the highest risk for onset of severe mental disorders or deliberate self-harm.

Evidence of the heritability of and neuropsychological pathways implicated in rumination is important as, for example, changes in the neural networks associated with CER may precede behavioural manifestations in unaffected high risk populations (Heissler et al. 2014). Critically, this review suggests ruminative response style is a putative shared mechanism for the development of sleep and physiological dysregulation and health problems in young adults with evolving mental disorders. This is relevant as attempts to explain physical and mental co-morbidities on the basis of factors such as the adverse physical effects of treatment or reduced daytime activity (post-onset of mental disorder) have proven to be overly simplistic and fail to take into account findings of the high levels of physical and mental co-morbidity in untreated, early stage cases. It appears that a ruminative response style may be associated with circadian and HPA disruptions, and its relationship to physical disease is not driven by greater reactivity in systems, but instead through extending activation and increasing allostatic load, which may increase the risks for cardiovascular or other damage (Larsen & Christenfeld, 2009). Indeed, Ottaviani et al. (2009) suggest that rumination represents an ‘autonomic phenotype’ because the associated autonomic dysregulation plays a role in the relationships between temperament, anxiety, depression and cardiovascular health.

In conclusion, this selective review of the association between rumination and the early clinical stages of mental disorders suggests that it is an important underlying trans-diagnostic process that operates in adolescents and young adults. Further, rumination shows a predictable developmental trajectory that is both detectable and modifiable. From the perspective of primary or early secondary prevention, modifying the maladaptive ‘toxic brooding’ component of rumination and substituting a more flexible response style that engenders a greater sense of self-control has the potential to reduce the onset or maintenance of problems such as depression and anxiety (Cook & Watkins, 2016), and may reduce the distress or severity of other disorders, such as psychosis and bipolar disorders (Vallarino et al. 2015; Scott, 2016). This review indicates that examination of rumination and other CER is an important, underexplored issue in trans-diagnostic and dimensional approaches to mental disorders, which is especially important given the apparent links to physical and well as mental health, and the prospects for modification of this risk factor.

Acknowledgements

A.G. has received grant funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia. I.B.H. is a Commissioner in Australia's National Mental Health Commission; a Member of the Medical Advisory Panel for Medibank; a Board Member of Psychosis Australia Trust. He has received honoraria for presentations of his own work at educational seminars supported by a number of non-government organizations and by the pharmaceutical industry (including Servier, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly) and funding from Servier for a study of major depression and sleep disturbance in primary-care settings. Other relevant funding for Professor Ian Hickie is in relation to this study includes ‘Testing and delivering early interventions for young people with depression’ (APP ID: 1046899). S.N. has received grant funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council including for research on sleep and actigraphy. J.S. is a visiting professor at the Brain & Mind Centre at The University of Sydney. J.S. has received UK grant funding from the Medical Research Council (including for projects on actigraphy and bipolar disorders) and from the Research for Patient Benefit programme (PB-PG-0609-16166: Early identification and intervention in young people at risk of mood disorders).

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Abela JR, Aydin CM, Auerbach RP (2007). Responses to depression in children: reconceptualizing the relation among response styles. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 35, 913–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian M, McCarty C, King K, McCauley E, Vander Stoep A (2014). The internalizing pathway to adolescent substance use disorders: mediation by ruminative reflection and ruminative brooding. Journal of Adolescence 37, 983–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens B, Linden M (1996). Is there a suicidality syndrome independent of specific major psychiatric disorder? Results of a split half multiple regression analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 94, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2012). When are adaptive strategies most predictive of psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KJ, Gabbay FH (2013). The amphetamine response moderates the relationship between negative emotionality and alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 37, 348–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Nusslock R, Boland EM (2015). The development and course of bipolar spectrum disorders: an integrated reward and circadian rhythm dysregulation model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 11, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers AR, Foti D (2015). Abnormal reward functioning across substance use disorders and major depressive disorder: considering reward as a transdiagnostic mechanism. International Journal of Psychophysiology 98, 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham PJ, Glozier N, Christensen H (2012). Sleep disturbance, personality and the onset of depression and anxiety: prospective cohort study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 46, 1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baynes D, Mulholland C, Cooper SJ, Montgomery RC, MacFlynn G, Lynch G, Kelly C, King DJ (2000). Depressive symptoms in stable chronic schizophrenia: prevalence and relationship to psychopathology and treatment. Schizophrenia Research 45, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beards S, Georgiades A, Sharma M, Kane F, Kalidindi S, Schulze K, Walshe M, Scott J, Murray R, Rijsdijk F, Kraviriti E (2012). Psychological endophenotypes for bipolar disorders Abstracts of the 3rd Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference, Florence, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Bechdolf A, Ratheesh A, Cotton SM, Nelson B, Chanen AM, Betts J, Bingmann T, Yung AR, Berk M, McGorry PD (2014). The predictive validity of bipolar at-risk (prodromal) criteria in help-seeking adolescents and young adults: a prospective study. Bipolar Disorders 16, 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Wells TT, McGeary JE (2009). The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism is associated with rumination in healthy adults. Emotion 9, 579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh KH, Crnic K (1996). Infant positive and negative emotionality: one dimension or two? Developmental Psychology, 32, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Berman MG, Nee DE, Casement M, Kim HS, Deldin P, Kross E, Gonzalez R, Demiralp E, Gotlib IH, Hamilton P, Joormann J, Waugh C, Jonides J (2011a). Neural and behavioral effects of interference resolution in depression and rumination. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 11, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman MG, Peltier S, Nee DE, Kross E, Deldin PJ, Jonides J (2011b). Depression, rumination and the default network. Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience 6, 548–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez J, Perez-Garcia AM (1996). Cardiovascular reactivity, affective responses and performance related to the risk dimensions of coronary-prone behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences 21, 919–927. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, Beesdo K, Höfler M, Lieb R (2004). What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65, 618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SW, Pössel P (2015). Integrating Beck's cognitive model and the response style theory in an adolescent sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 44, 195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Homann E (1992). Parent-child interaction in the aetiology of dependent and self-critical depression. Clinical Psychology Review 12, 47–91. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick PC (1998). Early adolescent gender differences in the use of ruminative and distracting coping strategies. Journal of Early Adolescence 18, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF (2010). Markers of chronic stress: prolonged physiological activation and (un)conscious perseverative cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 35, 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis: a review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 60, 113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D (1986). Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychological Bulletin 99, 66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney CE, Edinger JD, Meyer B, Lindman L, Istre T (2006). Symptom-focused rumination and sleep disturbance. Behavioral Sleep Medicine 4, 228–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli G, Bortolai C, Leoni M, Rovetto F, Spada MM (2008). Rumination in problem drinkers. Addiction Research & Theory 16, 564–571. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli G, Ferretti C, Leoni M, Rebecchi D, Rovetto F, Spada MM (2010). Rumination as a predictor of drinking behaviour in alcohol abusers: a prospective study. Addiction 105, 1041–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernis E, Dunn G, Startup H, Kingdon D, Wingham G, Evans N, Lister R, Pugh K, Cordwell J, Mander H, Freeman D (2015). The perseverative thinking questionnaire in patients with persecutory delusions. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 44, 472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Debono M (2010). Review: replication of cortisol circadian rhythm: new advances in hydrocortisone replacement therapy. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism 1, 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Miranda R, Surrence K (2009). Subtypes of rumination in the relationship between negative life events and suicidal ideation. Archives of Suicide Research 13, 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li X (2013). Genetic and environmental influences on adolescent rumination and its association with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 41, 1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus J, Paul G (2006). Stress exposure and stress generation in child and adolescent depression: a latent trait-state-error approach to longitudinal analyses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 115, 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE (1987). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin 101, 393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SL, Wagner CA, Shapero BG, Pendergast LL, Abramson LY, Alloy LB (2014). Rumination prospectively predicts executive functioning impairments in adolescents. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 45, 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway M, Csank PAR, Holm SL, Blake CK (2000). On assessing individual differences in rumination on sadness. Journal of Personality Assessment 75, 404–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway M, Mendelson M, Giannopoulos C, Csank PA, Holm SL (2004). Childhood and adult sexual abuse, rumination on sadness, and dysphoria. Child Abuse & Neglect 28, 393–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook L, Watkins ER (2016). Guided, internet-based, rumination-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (i-RFCBT) versus a no-intervention control to prevent depression in high-ruminating young adults, along with an adjunct assessment of the feasibility of unguided i-RFCBT, in the REducing Stress and Preventing Depression trial (RESPOND): study protocol for a phase III randomised controlled trial. Trials 17, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox SJ, Mezulis AH, Hyde JS (2010). The influence of child gender role and maternal feedback to child stress on the emergence of the gender difference in depressive rumination in adolescence. Developmental Psychology 46, 842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RN, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2000). Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and non-ruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research 24, 699–711. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong-Meyer R, Beck B, Riede K (2009). Relationships between rumination, worry, intolerance of uncertainty and metacognitive beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences 46, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Babor TF, Roebuck C, and Donaldson J (2002). Changing the focus: the case for recognizing and treating cannabis use disorders. Addiction 97, 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas J, Scott J (2014). A systematic review of gender-specific rates of unipolar and bipolar disorders in community studies of pre-pubertal children. Bipolar Disorders 16, 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Alda M, Hajek T, Grof P (2009). Early course of bipolar disorder in high-risk offspring: prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry 195, 457–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Schwartz A, Francis K (2004). Intolerance of uncertainty, worry, and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research 28, 835–842. [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad M, Chapman LJ (1986). Development and validation of a scale for hypomanic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 95, 214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Watkins ER (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 1, 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein DA (2014). Extension of the transdiagnostic model to focus on intolerance of uncertainty: a review of the literature and implications for treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 21, 280–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, King LA (1988). Conflict among personal strivings: immediate and long-term implications for psychological and physical well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54, 1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck MW (1985). Personality and Individual Differences. Plenum: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman GC, Joormann J, Johnson SL (2008). Responses to positive affect: a self-report measure of rumination and dampening. Cognitive Therapy and Research 32, 507–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D, Startup H, Dunn G, Černis E, Wingham G, Pugh K, Cordwell J, Kingdon D (2013). The interaction of affective with psychotic processes: a test of the effects of worrying on working memory, jumping to conclusions, and anomalies of experience in patients with persecutory delusions. Journal of Psychiatric Research 47, 1837–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Nelson B, Valmaggia L, Yung AR, McGuire PK (2014). Comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders in 509 individuals with an at-risk mental state: impact on psychopathology and transition to psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 40, 120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences 30, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Legerstee J, Kraaij V, Van Den Kommer T, Teerds JAN (2002). Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a comparison between adolescents and adults. Journal of Adolescence 25, 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V (2007). The cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 23, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, van Etten M (2005). Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Adolescence 28, 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehue LJ, Scott E, Hermens DF, Scott J, Hickie I (2015). Youth Early-intervention Study (YES) – group interventions targeting social participation and physical well-being as an adjunct to treatment as usual: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 16, 333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy PA, Leboyer M, Scott J (2013). Predicting bipolar disorder: what can we learn from prospective cohort studies? Encephale 41, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaznavi S, Deckersbach T (2012). Rumination in bipolar disorder: evidence for an unquiet mind. Biology of Mood and Anxiety Disorders 2, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianferante D, Thoma MV, Hanlin L, Chen X, Breines JG, Zoccola PM, Rohleder N (2014). Post-stress rumination predicts HPA axis responses to repeated acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 49, 244–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Grassia M, Stone LB, Uhrlass DJ, McGeary JE (2012). Brooding rumination and risk for depressive disorders in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 40, 317–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LM, Christenfeld N, Gerin W (2002). The role of rumination in recovery from reactivity: cardiovascular consequences of emotional states. Psychosomatic Medicine 64, 714–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeleven E, De Raedt R, Baert S, Koster EH (2006). Deficient inhibition of emotional information in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 93, 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Vyas NS, Testa R, Wood SJ, Pantelis C (2011). Age of onset of schizophrenia: perspectives from structural neuroimaging studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 37, 504–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL (2003). Mood regulation and emotional intelligence: individual differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84, 594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Carnethon MR, Matthews KA, McIntyre RS, Miller GE, Raghuveer G, Stoney CM, Wasiak H, McCrindle BW (2015). Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder predispose youth to accelerated atherosclerosis and early cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 132, 965–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hamilton JP (2008). Neuroimaging and depression current status and unresolved issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science 17, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J (2010). Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 6, 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Lino BJ, Hwang EJ, Sparks A, James C, Mitchell PB (2011). Cognitive regulation of emotion in bipolar I disorder and unaffected biological relatives. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 124, 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Munoz RF (1995). Emotion regulation and mental health. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurak A, Gross JJ, Etkin A (2011). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: a dual-process framework. Cognition and Emotion 25, 400–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner H, Maurer K, Löffler W, Fatkenheuer B (1994). The epidemiology of early schizophrenia influence of age and gender on onset and early course. British Journal of Psychiatry 164, 29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halari R, Premkumar P, Farquharson L, Fannon D, Kuipers E, Kumari V (2009). Rumination and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 197, 703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Hamlat EJ, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB (2014a). Pubertal timing and vulnerabilities to depression in early adolescence: differential pathways to depressive symptoms by sex. Journal of Adolescence 37, 165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Kleiman EM, Hamlat EJ, Abramson LY, Alloy LB (2014b). Cognitive vulnerabilities amplify the effect of early pubertal timing on interpersonal stress generation during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43, 824–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JP, Furman DJ, Chang C, Thomason ME, Dennis E, Gotlib IH (2011). Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biological Psychiatry 70, 327–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel P, Petermann F (2005). Age and gender effects on coping in children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 34, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Oppenheimer C, Jenness J, Barrocas A, Shapero BG, Goldband J (2009). Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: review of processes contributing to stability and change across time. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65, 1327–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley S, Haddock G, Vasconcelos e Sa D, Emsley R, Barrowclough C (2014). An experience sampling study of worry and rumination in psychosis. Psychological Medicine 44, 1605–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Watkins ER, Mansell W, Shafran R (2004). Cognitive Behavioural Processes Across Psychological Disorders: A Transdiagnostic Approach to Research and Treatment. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Heissler J, Kanske P, Schonfelder S, Wessa M (2014). Inefficiency of emotion regulation as vulnerability marker for bipolar disorder: evidence from healthy individuals with hypomanic personality. Journal of Affective Disorders 152, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Burnam A, McEvoy LT (1991). Alcohol abuse and dependence In Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study, (ed. Robins L. and Regier D.), pp. 81–115. MacMillan: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Hickie IB, Naismith SL, Robillard R, Scott EM, Hermens DF (2013). Manipulating the sleep-wake cycle and circadian rhythms to improve clinical management of major depression. BMC Medicine 11, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ (2012). Early family context and development of adolescent ruminative style: moderation by temperament. Cognition & Emotion 26, 916–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Sander LC, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Simen AA (2007). The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism predicts rumination and depression differently in young adolescent girls and their mothers. Neuroscience Letters 429, 12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn PJ, Wuyek LA (2010). Anxiety disorders as a risk factor for subsequent depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice 14, 244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou WK, Ng SM (2014). Emotion-focused positive rumination and relationship satisfaction as the underlying mechanisms between resilience and psychiatric symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences 71, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Rapee RM (2004). From anxious temperament to disorder: an etiological model of generalized anxiety disorder In Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice (ed. Heimberg R. G., Turk C. L. and Mennin D. S.), pp. 51–76. Guilford Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY (2008). The ABCs of depression: integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review 115, 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, Sanislow C, Wang P (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 167, 748–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RH, Jenkins LM, Gabriel LB, Barba A, Ryan KA, Weisenbach SL, Verges A, Baker AM, Peters AT, Crane NA, Gotlib IH, Zubieta JK, Phan KL, Langenecker SA, Welsh RC (2014). Increased coupling of intrinsic networks in remitted depressed youth predicts rumination and cognitive control. PLoS ONE 9, . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, McKenzie G, McMurrich S (2008). Ruminative responses to negative and positive affect among students diagnosed with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research 32, 702–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NP, Papadakis AA, Hogan CM, Strauman TJ (2009). Over and over again: rumination, reflection, and promotion goal failure and their interactive effects on depressive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy 47, 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PB (2013). Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. British Journal of Psychiatry 202(s54), s5–s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SH, Tai S, Evershed K, Knowles R, Bentall R (2006). Early detection of bipolar disorder: a pilot familial high-risk study of parents with bipolar disorder and their adolescent children. Bipolar Disorders 8, 362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, Fernyhough C (2009). Rumination, reflection, intrusive thoughts, and hallucination-proneness: towards a new model. Behaviour Research and Therapy 47, 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J (2004). Attentional bias in dysphoria: the role of inhibitory processes. Cognition and Emotion 18, 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Gotlib IH (2008). Updating the contents of working memory in depression: interference from irrelevant negative material. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 117, 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Nee DE, Berman MG, Jonides J, Gotlib IH (2010). Interference resolution in major depression. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience 10, 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Brown I (2008). When does the gender difference in rumination begin? Gender and age differences in the use of rumination by adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 37, 180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Ratcliffe V (2004). Stressor frequency and perceived intensity as predictors of internalizing symptoms: gender and age differences in adolescence. New Zealand Journal of Psychology 33, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Weir KF (2013). How is anxiety involved in the longitudinal relationship between brooding rumination and depressive symptoms in adolescents? Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42, 1210–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Wilkins H, Spendelow JS (2012). Does social anxiety predict rumination and co-rumination among adolescents?. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 41, 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ḳaminer Y, Bukstein OG (2008). Adolescent Substance Abuse: Psychiatric Comorbidity and High-Risk Behaviors. Taylor & Francis: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key BL, Campbell TS, Bacon SL, Gerin W (2008). The influence of trait and state rumination on cardiovascular recovery from a negative emotional stressor. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 31, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles R, Tai S, Christensen I, Bentall R (2005). Coping with depression and vulnerability to mania: a factor analytic study of the Nolen-Hoeksema (1991). Response Styles Questionnaire. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 44, 99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij V, Garnefski N, de Wilde EJ, Dijkstra A, Gebhardt W, Maes S, ter Doest L (2003). Negative life events and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: bonding and cognitive coping as vulnerability factors?. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 32, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Watkins ER, Holden E, Cook W (2006). Rumination in adolescents at risk for depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 96, 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers F, van Oppen P, Comijs HC, Smit JH, Spinhoven P, Van Balkom AJ, Penninx BW (2011). Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72, 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BA, Christenfeld NJ (2009). Cardiovascular disease and psychiatric comorbidity: the potential role of perseverative cognition. Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology, vol. 2009, doi: 10.1155/2009/791017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last CG, Hansen C, Franco N (1997). Anxious children in adulthood: a prospective study of adjustment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 36, 645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR (1998). Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review 18, 765–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao KYH, Wei M (2011). Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: the moderating and mediating roles of rumination. Journal of Clinical Psychology 67, 1220–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok CF, Bishop GD (1999). Emotion control, stress, and health. Psychology and Health 14, 813–827. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Caldwell ND, Nolen-Hoeksema S (1998). Effects of ruminative and distracting responses to depressed mood on retrieval of autobiographical memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75, 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Rutherford E, Campbell L, Ebsworthy G, Holker L (2002). Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 111, 107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggini C, Raballo A (2006). Exploring depression in schizophrenia. European Psychiatry 21, 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi C, Caselli G, Rovetto F, Rebecchi D, Ruggiero GM, Sassaroli S, Spada MM (2011). Temperament and parental styles as predictors of ruminative brooding and worry. Personality and Individual Differences 50, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti I, Koster EH, Sonuga-Barke EJ, De Raedt R (2012). The default mode network and recurrent depression: a neurobiological model of cognitive risk factors. Neuropsychology Review 22, 229–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Carey TA (2013). Perceptual control theory as an integrative framework for clinical interventions In Cognitive Behavioural Approaches to the Understanding and Treatment of Dissociation (ed. Kennedy F., Kennerley H. and Pearson D.), pp. 221–235. Routledge: London. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LL, Tesser A, McIntosh WD (1993). Wanting but not having: The effects of unattained goals on thoughts and feelings In Handbook of Mental Control (ed. Wegner D. M. and Pennybaker J. W.), pp. 552–572. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, US. [Google Scholar]