Abstract

Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) is a phase I enzyme that regulates the metabolism of environmental carcinogens and alter the susceptibility to various cancers. Many studies have investigated the association between the CYP1A1 MspI and Ile462Val polymorphisms and digestive tract cancer (DTC) risk in different groups of populations, but their results were inconsistent. The PubMed and Embase Database were searched for case–control studies published up to 30th September, 2015. Data were extracted and pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the relationship. Totally, 39 case–control studies (9094 cases and 12,487 controls) were included. The G allele in Ile/Val polymorphism was significantly associated with elevated DTC risk with per‐allele OR of 1.24 (95% CI = 1.09–1.41, P = 0.001). Similar results were also detected under the other genetic models. Evidence was only found to support an association between MspI polymorphism and DTC in the subgroups of caucasian and mixed individuals, but not in the whole population (the dominant model: OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 0.94–1.91, P = 0.146). In conclusion, our results suggest that the CYP1A1 polymorphisms are potential risk factors for DTC. And large sample size and well‐designed studies with detailed clinical information are needed to more precisely evaluate our founding.

Keywords: CYP1A1, digestive tract cancer, polymorphism, meta‐analysis

Introduction

Digestive tract cancers (DTCs), well known as the most common malignant tumours globally, include oesophageal, gastric and colorectal cancers 1, 2, 3, 4. Data from Global Cancer Statistics, 2012 1 suggest that DTC has contributed to an enormous burden on society today. Actually, colorectal cancer is confirmed as the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in males and the second in females. Both the incidence rates of gastric cancer and oesophageal cancer keep the highest in Eastern Asia. Despite of the updating advances in surgery and chemotherapy, DTC remains the high‐mortality disease, even the leading cause of cancer‐related death 4. As generally accepted, the mechanism of the digestive tract tumorigenesis is a comprehensive combination of multiple risk factors including environmental conditions, dietary habits and genetic predispositions 5, 6, 7. Among these, metabolism‐associated genetic susceptibility has become an important focus. As a member of the CYP1 family, Cytochrome P4501A1 (CYP1A1) regulates the metabolism of many endogenous and exogenous carcinogens 3, 8, 9. CYP1A1, as its protein‐coding gene, is located on Chr15q22~q14, encoding aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. Aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase is active in metabolizing some pro‐carcinogens, particularly the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), into intermediates. The intermediate substitutes may contribute to carcinogenesis eventually if bind to DNA and form adducts 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.

CYP1A1 gene consists of many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). These diverse variants could break the initial physiological equilibrium between activation and detoxification of metabolic carcinogens by adjusting the quantity and function of such enzyme. The two functional polymorphisms in CYP1A1gene, MspI (T >C, occurring in the noncoding 3′‐flanking region, rs4646903) and Ile462Val (A>G, found at codon 462 in exon 7, rs1048943), may associate with the risk of DTC by the mechanism above 9.

Many studies have been carried out to examine the association between the two polymorphisms of CYP1A1 and risk of many cancers 9. However, because of different subject selections, the results were inconsistent. In addition, the relationship for DTC risk has been only explored in Chinese population by Liu et al. 14. Hence, to further explore that association in the whole of humanity and clarify the former results, we conduct this meta‐analysis with more eligible studies.

Materials and methods

Literature search strategy

The published case–control studies about the associations between the CYP1A1 polymorphisms and DTC were searched manually on PubMed and Embase Database up to 30th September, 2015. The search was limited to English language papers, using the key words ‘(CYP1A1 or P4501A1 or MspI or exon7 or Ile/Val or cytochrome)’ and ‘polymorphism’ and ‘(colorectal cancer or gastric cancer or oesophageal cancer)’. And the following criteria were established: (i) case–control studies, (ii) exploring the association between MspI or Ile/Val polymorphism and DTC, (iii) DTC confirmed histologically or pathologically, (iv) providing sufficient data to calculate the odds ratio (OR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) and P‐value. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) a case report or a review, (ii) no sufficient genotype frequency, (iii) a duplicated publication 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.

Data extraction

Based on the inclusion criteria listed above, two authors independently extracted data from all qualified publications. Controversies were eliminated through discussion with another investigator. Following data were collected: first author’ s name, year of publication, cancer type, country and ethnicity of population, genotyping method, source of controls, number of cases and controls with different genotypes, adjusted OR and 95% CI and adjustment of variables if available and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) 14, 15 (See in Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of CYP1A1 MspI polymorphism included in the meta‐analysis

| Year | Ethnicity | Source | Case | Control | Method | Sample size | P for HWE | OR 95% CIa | Adjustment of variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Genotypes | N | Genotypes | CT/TT | CC/TT | ||||||||||||

| TT | TC | CC | TT | TC | CC | ||||||||||||

| MspI | |||||||||||||||||

| EC | |||||||||||||||||

| Jain et al. | 2007 | Asian | PB | 171 | 59 | 83 | 19 | 201 | 79 | 99 | 23 | PCR | ≥300 | 0.629 | 1.1 (0.71–1.7) | 1.1 (0.55–2.2) | Age, gender, smoking, drinking |

| Malik et al. | 2010 | Asian | PB | 135 | 76 | 52 | 7 | 195 | 95 | 88 | 12 | MLPA | ≥300 | 0.361 | 0.72 (0.45–1.14) | 0.70 (0.26–1.87) | Age, gender |

| GC | |||||||||||||||||

| Ma et al. | 2006 | Asian | PB | 60 | 26 | 27 | 7 | 57 | 26 | 28 | 3 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.423 | – | – | – |

| Malik et al. | 2009 | Asian | HB | 108 | 60 | 46 | 2 | 195 | 95 | 88 | 12 | PCR | ≥300 | 0.361 | 0.84 (0.52–1.37) | 0.34 (0.07–1.60) | Age, gender |

| Luo et al. | 2011 | Asian | PB | 123 | 38 | 61 | 24 | 129 | 47 | 54 | 28 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.261 | – | – | – |

| Ghoshal et al. | 2014 | Asian | PB | 88 | 41 | 36 | 11 | 170 | 78 | 80 | 12 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.370 | – | – | – |

| Darazy et al. | 2011 | Caucasian | PB | 11 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 56 | 54 | 1 | 1 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.000 | 0.87 (0.5–1.5) | 1.8 (0.7–4.4) | Age, gender |

| CC | |||||||||||||||||

| Sivaraman et al. | 1994 | Mixed | PB | 43 | 23 | 10 | 10 | 47 | 23 | 22 | 2 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.508 | – | – | – |

| Ye et al. | 2002 | Caucasian | NR | 41 | 35 | 6 | 0 | 82 | 73 | 9 | 0 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.871 | – | – | – |

| Talseth et al. | 2006 | Caucasian | NR | 118 | 94 | 20 | 4 | 100 | 91 | 9 | 0 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.895 | – | – | – |

| Darazy et al. | 2011 | Caucasian | PB | 46 | 42 | 2 | 2 | 56 | 54 | 1 | 1 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.000 | – | – | – |

| Saeed et al. | 2013 | Asian | HB | 94 | 70 | 21 | 3 | 79 | 73 | 6 | 0 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.940 | – | – | – |

| Rudolph et al. | 2011 | German | PB | 679 | 539 | 134 | 6 | 679 | 564 | 102 | 13 | KASPar assays | ≥300 | 0.007 | – | – | – |

Significance of bold value: P < 0.05 for HWE is considered as significant disequilibrium.

Adjusted. EC: oesophageal cancer; GC: gastric cancer; CC: colorectal cancer; HB: Hospital based; PB: Population based; NR: no record; HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; PCR‐RFLP: polymerase chain reaction‐restriction fragment length polymorphism; PCR–ASO: PCR–allele specific oligonucleotide.

Table 2.

Characteristics of CYP1A1 Ile462Val polymorphism included in the meta‐analysis

| Study | Year | Ethnicity | Source | Case | Control | Method | Sample size | P for HWE | OR 95% CIa | Adjustment of variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Genotypes | N | Genotypes | GA/AA | GG/AA | ||||||||||||

| AA | AG | GG | AA | AG | GG | ||||||||||||

| Ile462Val | |||||||||||||||||

| EC | |||||||||||||||||

| Morita et al. | 1997 | Asian | HB | 53 | 32 | 20 | 1 | 132 | 80 | 49 | 3 | PCR | <300 | 0.355 | – | – | – |

| Nimura et al. | 1997 | Asian | HB | 89 | 50 | 26 | 13 | 137 | 92 | 38 | 7 | PTC‐150 | <300 | 0.518 | – | – | – |

| Hori et al. | 1997 | Asian | NR | 101 | 62 | 37 | 2 | 428 | 275 | 133 | 20 | nonRI‐SSCP | ≥300 | 0.752 | – | – | – |

| Lieshout et al. | 1999 | Caucasian | NR | 34 | 26 | 8 | 0 | 247 | 207 | 37 | 3 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.665 | – | – | – |

| Wang et al. | 2002 | Asian | HB | 127 | 25 | 58 | 44 | 101 | 31 | 48 | 22 | PCR | <300 | 0.915 | – | – | – |

| Wu et al. | 2002 | Asian | HB | 146 | 68 | 62 | 16 | 324 | 179 | 127 | 18 | PCR‐RFLP | ≥300 | 0.762 | 1.34 (0.86–2.07) | 2.48 (1.15–5.34) | Age, education, ethnicity, smoking, drinking, and areca consumption |

| Wang et al. | 2003 | Asian | PB | 62 | 30 | 28 | 4 | 38 | 20 | 16 | 2 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.870 | – | – | – |

| Wang et al. | 2004 | Asian | HB | 127 | 21 | 56 | 50 | 101 | 31 | 48 | 22 | PCR | <300 | 0.915 | 1.7 (0.83–3.58) | 3.3 (1.49–7.61) | Tobacco smoking、alcohol drinking、FHEC |

| Abbas et al. | 2004 | Caucasian | PB | 79 | 61 | 9 | 9 | 130 | 101 | 6 | 23 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.000 | 2.63 (0.84–8.28) | – | Age, sex |

| Wang et al. | 2012 | Asian | PB | 565 | 304 | 225 | 36 | 468 | 295 | 154 | 19 | PCR | ≥300 | 0.981 | – | – | |

| Yun et al. | 2013 | Asian | PB | 157 | 73 | 72 | 12 | 157 | 95 | 50 | 12 | PCR‐RFLP | ≥300 | 0.348 | 2.05 (1.19–3.54) | 1.12 (0.41–3.04) | Age, gender, smoking, drinking and FHC |

| GC | |||||||||||||||||

| Suzuki et al. | 2004 | Asian | HB | 144 | 84 | 51 | 9 | 177 | 104 | 65 | 8 | PCR | ≥300 | 0.865 | – | – | |

| Li et al. | 2005 | Asian | HB | 102 | 53 | 27 | 22 | 62 | 35 | 24 | 3 | PCR | <300 | 0.910 | 0.59 (0.26–1.34) | 5.91 (1.28–27.24) | Age, sex, education, job, drinking, smoking |

| Shen et al. | 2005 | Asian | PB | 112 | 70 | 36 | 6 | 676 | 412 | 226 | 38 | PCR‐RFLP | ≥300 | 0.639 | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 0.7 (0.2–1.8) | Age, gender, living areas, FHC, drinking |

| Agudo et al. | 2006 | Caucasian | PB | 243 | 229 | 13 | 1 | 936 | 874 | 62 | 0 | SNP500cd | ≥300 | 0.578 | 0.90 (0.48–1.68) | – | Age, sex, centre, and date of blood extraction |

| Kobayashi et al. | 2009 | Asian | HB | 141 | 91 | 44 | 6 | 286 | 162 | 109 | 15 | MassARRAY system | ≥300 | 0.832 | 0.79 (0.40–1.57) | 2.01 (0.45–9.48) | H. p status, smoking, drink, FHGC, BMI, total food intake, JA membership |

| CC | |||||||||||||||||

| Sivaraman et al. | 1994 | Mixed | PB | 43 | 32 | 9 | 2 | 47 | 33 | 14 | 0 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.487 | – | – | – |

| Kiss et al. | 2000 | Mixed | PB | 163 | 119 | 41 | 3 | 163 | 132 | 31 | 0 | PCR‐ASO | ≥300 | 0.407 | – | – | – |

| Slattery et al. | 2004 | Mixed | HB | 1791 | 1632 | 148 | 11 | 2180 | 1997 | 171 | 12 | PCR | ≥300 | 0.001 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 1.5 (0.5, 4.9) | Age, sex |

| Little et al. | 2006 | Caucasian | PB | 251 | 235 | 16 | 0 | 396 | 372 | 24 | 0 | PCR | ≥300 | 0.824 | 1.31 (0.59–2.91) | – | Age, sex, FHCC, aspirin use, use of other NSAIDs and physical activity |

| Yeh et al. | 2007 | Asian | HB | 717 | 400 | 228 | 89 | 729 | 410 | 266 | 53 | PCR‐RFLP | ≥300 | 0.558 | – | – | – |

| Yoshida et al. | 2007 | Asian | NR | 66 | 34 | 27 | 5 | 121 | 79 | 37 | 5 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.968 | 1.54 (0.78–3.04) | 1.99 (0.41–9.63) | Age, gender, smoking habit |

| Pereira Serafim et al. | 2008 | Mixed | PB | 114 | 14 | 97 | 3 | 114 | 81 | 33 | 0 | PCR‐RFLP | <300 | 0.196 | – | – | – |

| Kobayashi et al. | 2009 | Asian | HB | 105 | 65 | 32 | 8 | 225 | 125 | 87 | 13 | Mass ARRAY system | ≥300 | 0.915 | 0.43 (0.171.06) | 0.76 (0.144.13) | Smoking, drinking, FHCC, BMI, JA membership, and intake of other food |

| Nisa et al. | 2010 | Asian | PB | 685 | 418 | 231 | 36 | 778 | 461 | 276 | 41 | PCR‐RFLP | ≥300 | 0.999 | 0.94 (0.75–1.17) | 1.00 (0.62–1.62) | Age, sex, residence, smoking, drinking, BMI, job, physical activity, FHCC |

| Cleary et al. | 2010 | Caucasian | PB | 1160 | 1052 | 98 | 10 | 1288 | 1166 | 114 | 8 | Taq‐man | ≥300 | 0.023 | 0.95 (0.71, 1.27) | 1.37 (0.53, 3.55) | Age, sex |

Significance of bold value: P < 0.05 for HWE is considered as significant disequilibrium.

Adjusted. EC: oesophageal cancer; GC: gastric cancer; CC: colorectal cancer; HB: Hospital based; PB: Population based; NR: no record; HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; PCR‐RFLP: polymerase chain reaction‐restriction fragment length polymorphism; PCR–ASO: PCR–allele specific oligonucleotide; FHEC: family history of EC.

Statistical analysis

The HWE in control group was assessed by Pearson's goodness‐of‐fit chi‐square test and P < 0.05 was considered as significant disequilibrium. OR and 95% CI were calculated for CYP1A1 MspI/Ile462Val polymorphisms and DTC risk in each study. The pooled OR was also determined by the Z‐test (if P < 0.05, then considered as significant). Stratified analyses by cancer type, source of controls, ethnicity, sample size and genotyping method were performed 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.The influence of study size of each evaluated publication on the results was assessed by the weight.

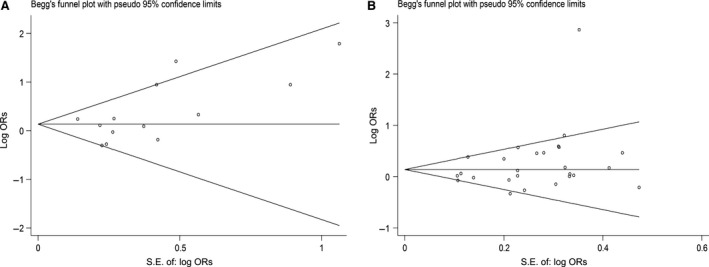

Heterogeneity in our meta‐analysis was assessed by the chi‐square‐based Q‐test and I 2. A fixed‐effects model (the Mantel–Haenszel method) was applied if P > 0.05, which indicated no or little heterogeneity among eligible studies. Otherwise, the random‐effects model (Der Simonian and Laird method) was used. Galbraith graph was performed to explore the source of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was tested to assess the stability of our results. The funnel plot was performed for potential publication bias. Funnel plot asymmetry was statistically assessed by Egger's linear regression test (publication bias exists if P < 0.05). All statistical analyses were carried out by Stata software (version 12.0, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) 13, 14, 15.

Results

Characteristics of studies

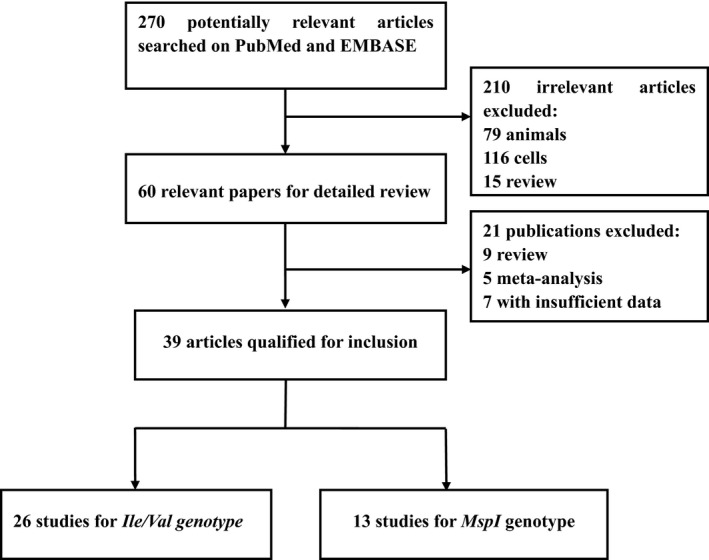

Totally 37 publications 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 containing 39 studies (6 pieces not consistent with HWE were also included), which investigated the relationship between CYP1A1 (MspI rs4646903 or Ile/Val rs1048943) polymorphisms and DTC risk, were included in the present meta‐analysis. The literature selection process was illustrated in Figure 1. All the eligible studies involved 9094 DTC cases and 12,487 controls. 13 studies (2 oesophageal cancer studies, 5 gastric cancer studies and 6 colorectal cancer studies) were identified for the MspI polymorphism, including a total of 1717 cases and 2046 controls. And for the Ile/Val polymorphism, 26 studies (11 oesophageal cancer studies, 5 gastric cancer studies and 10 colorectal cancer studies) were retrieved, covering a total of 7377 cases and 10,441 controls. More detailed charismatics about population source, ethnicity distribution, sample size, genotyping method and adjusted OR and 95% CI and adjustment of variables if available can be seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Studies identified with criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

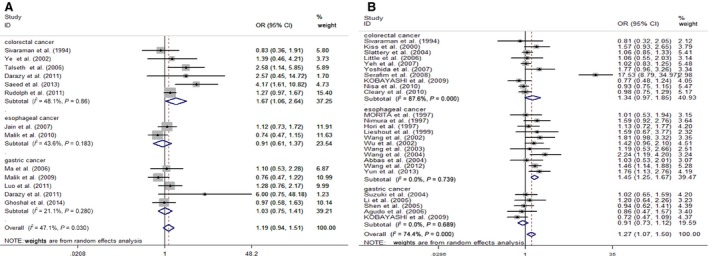

Association of MspI with digestive tract cancer

Overall, no sufficient evidence was found to support an association between increased susceptibility of DTC and MspI (rs4646903) polymorphism in all genetic models when all the eligible case–control studies were pooled together. Moreover, the adjusted pooled result was consistent with the crude one (data shown in Table 3 and Fig. 2A for the dominant model). In subgroup analysis by cancer type, a significant association was only found between MspI polymorphism and elevated colorectal cancer risk (the allele contrast: OR = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.16–2.86, P = 0.010). However, because of unavailable adjusted data on colorectal cancer, this positive result could not be validated (Fig. S1). Stratifying for ethnicity, an increased susceptibility was found in individuals with CC genotype among Caucasians and mixed population (the codominant model: OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.06–1.82, P = 0.018; OR = 5.7, 95% CI = 1.37–23.60, P = 0.016 respectively). However, no evidence was observed to prove that among Asians. In the stratified analysis by the source of controls, sample size or genotyping method, some statistical correlations were observed in the group of ‘population with sources unreported (NR)’, ‘size <300’ and ‘PCR‐RFLP method’ respectively (data shown in Table S1).

Table 3.

The overall results for MspI and Ile462Val polymorphisms in CYP1A1 and digestive tract cancer risk

| OR | 95% CI | P | I 2 (%) | Ph | ORa | 95% CIa | P a | I 2 (%)a | Ph a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MspI | |||||||||||

| Allele | C/T | 1.24 | 0.99–1.54 | 0.058 | 59.60% | 0.003 | – | – | – | ||

| Dominant | CC+CT/TT | 1.19 | 0.94–1.91 | 0.146 | 47.10% | 0.030 | – | – | – | ||

| Resessive | CC/CT+TT | 1.32 | 0.80–2.17 | 0.283 | 49.50% | 0.026 | – | – | – | ||

| Codominant | CT/TT | 1.12 | 0.88–1.42 | 0.341 | 42.00% | 0.055 | 0.88 | 0.69–1.12 | 0.296 | 0.0% | 0.624 |

| CC/TT | 1.30 | 0.80–1.21 | 0.296 | 43.50% | 0.053 | 1.01 | 0.64–1.62 | 0.937 | 24.4% | 0.265 | |

| Ile462Val | |||||||||||

| Allele | G/A | 1.24 | 1.09–1.41 | 0.001 | 69.40% | 0.000 | – | – | – | ||

| Dominant | GA+GG/AA | 1.27 | 1.07–1.50 | 0.006 | 74.40% | 0.000 | – | – | – | ||

| Resessive | GG/AA+GA | 1.49 | 1.21–1.82 | 0.000 | 22.30% | 0.157 | – | – | – | ||

| Codominant | GA/AA | 1.21 | 1.02–1.45 | 0.032 | 74.20% | 0.000 | 1.03 | 0.92–1.67 | 0.593 | 37.9% | 0.074 |

| GG/AA | 1.58 | 1.24–2.00 | 0.000 | 35.40% | 0.042 | 1.49 | 1.23–1.96 | 0.005 | 30.1% | 0.160 | |

Significance of bold value: P < 0.05 means a significant relationship between the polymorphism and digestive tract cancer risk.

Adjusted. Ph: P‐value of Q‐test for heterogeneity identification; I 2 index: a quantitative measurement which indicates the proportion of total variation in study estimates that is due to between‐study heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

(A) Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with MspI polymorphism (the dominant model CC + CT versus TT). (B) Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with Ile/Val polymorphism (the dominant model GA+GG versus AA).

Association of Ile/Val with digestive tract cancer

The G allele was significantly associated with elevated DTCs risk with per‐allele OR of 1.24 (95% CI = 1.09–1.41, P = 0.001). Similar results were also detected under other genetic models and in our adjusted pooled result (data shown in Table 3 and Fig. 2B, the dominant model). In the further subgroup analysis based on tumour type, the statistics strongly supported the significant relationship between Ile/Val and the chance of suffering oesophageal and colorectal cancer (the allele contrast: OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.19–1.56, P = 0.000, OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.01–1.61, P = 0.043 respectively). But the positive result was only observed in oesophagus cancer from the adjusted result partially together (Fig. S2). A significant association was also observed in Asians (the codominant model: OR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.26–2.09, P = 0.000), but not in caucasians or mixed individuals. Stratified by the source of controls, significant association was observed both in HB and NR group. Stratified by sample size and genotyping method, associations were found in most groups. Detailed analyses of the genetic variant are provided in Table S2.

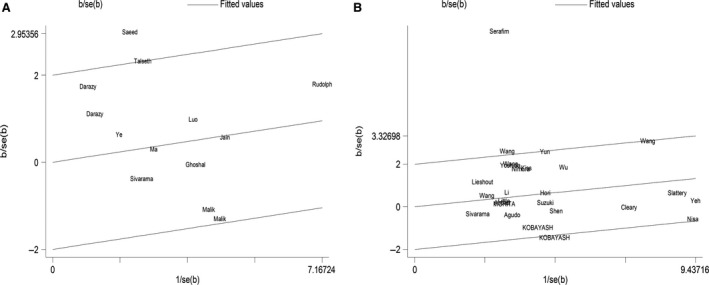

Heterogeneity analyses

For MspI polymorphism, moderate heterogeneity was detected (e.g. the dominant model: I 2 = 47.1%, Ph = 0.030). As shown in Tables S3 and S4, subgroup analyses stratified by cancer type, ethnicity, source of controls, sample size and genotyping method could not explain the source of heterogeneity at length. Hence, to further explore the heterogeneity source, we performed Galbraith graph. The study conducted by Saeed et al. 24 may be the main source of heterogeneity (data shown in Fig. 3A). Removing this study, the result of the meta‐analysis did not change essentially (e.g. the dominant mode: OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 0.90–1.35, P = 0.336), but its heterogeneity decreased significantly (the dominant model: I 2 = 28.6%, Ph = 0.165) (Fig. S3). Similar results were observed in other genetic models. In the same way, we found the source of heterogeneity in Figure 3B for Ile/Val polymorphism. When we removed the study conducted by Pereira Serafim et al. 47, the heterogeneity decreased sharply, while the results remained qualitatively (the dominant mode: OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.03–1.27, P = 0.016; I 2 = 34.8%, Ph = 0.046) (Fig. S4).

Figure 3.

(A) Galbraith graph for MspI polymorphism (the dominant model CC + CT versus TT): the study conducted by Saeed et al. may be the main source of heterogeneity. (B) Galbraith graph for Ile/Val polymorphism (the dominant model GA+GG versus AA): the study conducted by Pereira Serafim et al. may be the main source of heterogeneity.

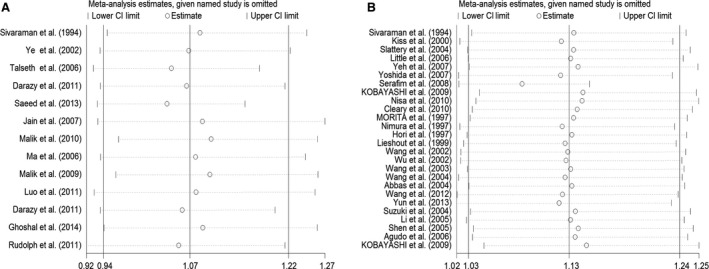

Sensitivity analyses

The corresponding pooled ORs were not qualitatively influenced when any particular study had been removed from the meta‐analysis (including the studies not conforming to HWE) for the two polymorphisms respectively (see in Fig. 4A and B). It confirmed that the results of the present meta‐analysis are reliable and stable.

Figure 4.

(A) Influence analysis of the summary odds ratio coefficients on the association between MspI polymorphism with digestive tract cancers risk (the dominant model CC + CT versus TT). Results were computed by omitting each study (left column) in turn. Bars, 95% CI. (B) Influence analysis of the summary odds ratio coefficients on the association between Ile/Val polymorphism with digestive tract cancers risk (the dominant model GA + GG versus AA). Results were computed by omitting each study (left column) in turn. Bars, 95% CI.

Publication Bias

Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test were performed to diagnose the publication bias of papers. The shapes of the funnel plots did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry in all comparison models for MspI (e.g. the dominant model in Fig. 5A). Statistically the results of both tests showed no publication bias (Begg's test P = 0.127, Egger's test P = 0.136, t = 1.61, 95% CI = −0.46 to 2.97). Regarding Ile/Val, no publication bias was detected as well in the dominant model (Begg's test P = 0.071, Egger's test P = 0.085, t = 1.80, 95% CI = −0.23 to 3.30) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Begg's funnel plot for publication bias test for MspI polymorphism (the dominant model CC + CT versus TT). Each point represents a separate study for the indicated association. (B) Begg's funnel plot for publication bias test Ile/Val polymorphism (the dominant model GA+GG versus AA). Each point represents a separate study for the indicated association.

Discussion

CYP1A, the subfamily of Cytochrome P450, is an important phase I metabolic enzyme. As a key subtype of CYP1A, CYP1A1 is distributed widely in the kidney, lung, stomach, colon, larynx, placenta, skin, lymphocyte, brain and other tissues 14. What's more, recent studies have demonstrated that it involves the metabolism of some exogenous carcinogens such as PAHs. CYP1A1 gene can promote the carcinogenic process by converting PAHs into their ultimate DNA‐binding forms 11.

MspI and Ile/Val, the main gene polymorphisms of CYP1A1, have been both verified associated with many kinds of cancers by large number of meta‐analyses 9. However, inconsistent results have been reported. To clarify this inconsistency, this meta‐analysis was established. To our best knowledge, it is the first one to explore the association of CYP1A1 polymorphisms and DTC risk in the whole population. Correlation association between CYP1A1 Ile/Val polymorphism and DTC susceptibility were detected in our meta‐analysis. While no evidence showed the association between CYP1A1 MspI polymorphism and DTC risk. The overall result is consistent with that of the meta‐analysis performed by Liu et al. 14 which was designed only in Chinese population.

Stratified by cancer type, the MspI CC genotype carriers were confirmed with an increased susceptibility to colorectal cancer but not to oesophageal or gastric cancer. While an A to G mutation in Ile/Val polymorphism increased the cancer risk in EC and CC groups. The results were partially inconsistent with Wu et al. 9. In fact, the studies we included in the present meta‐analysis were updated compared with Wu et al. And unhealthy eating habits could contribute to the digestive tract damage, such as excessive drinking. That is why different primary cancers of digestive tract may be caused by similar risk factors 13. On the other hand, DTC includes so many kinds of malignant tumours that heterogeneities among them will be found. One reason for the issue may be that the gene–gene and gene–environment interactions mechanisms differ in diverse digestive tract parts. To our common knowledge, some of the digestive tract tumours have their specific risk factors. For instance eating spicy and hot food can evaluate the risk of oesophageal cancer, whereas diet with high fat and low fibre may enhance the incidence of colorectal cancer. In addition, researchers have verified that Helicobacter pylori infection significantly increased susceptibility to gastric cancer 5, 6, 13, 18. In a word, the aetiological factors sensitive to various types of DTCs are not all the same. In the subgroup analysis by ethnicity, significant difference was detected in caucasian and mixed group for MspI polymorphism. Interestingly, high correlativity was otherwise observed in Asian group for Ile/Val polymorphism. This think‐provoking phenomenon may excellently reveal that genetic diversity exactly exists among various ethnicities across countrywide. Individuals, disturbing in different places of the world, will experience different environments, including climate, temperature and radiation 7 and will form diverse lifestyles especially a variety of eating habits. Both of the above will contribute to the genetic background discrepancy among ethnicities. In addition, we conduct two subgroup analyses for adjusted status (Yes or no) and adjusted status especially for smoking history (Yes or no) for Ile/Val polymorphism. The result in every subgroup is corresponding (Table S5), which verified the reliability of our results again. As the number of studies with adjusted data for MspI polymorphism is only 4, and moreover, only one study provided adjusted data for smoking, we did not carry out the analyses for MspI polymorphism.

Some limitations and potential bias cannot be ignored in our meta‐analysis. First, we centre on the heterogeneity. Moderate and high heterogeneity were detected among the studies for MspI and Ile/Val respectively. Through Galbraith graph, we found the study conducted by Saeed et al. 24 count for the main source of heterogeneity for MspI. For Ile/Val, the heterogeneity mainly came from study conducted by Pereira Serafim et al. 47. Through reviewing the two papers, we found some reasons to explain that. In the former study, the population was from Saudi Arabia and the number of case and control group is 94/79. While in the later, the population was from Brazil and the number of case and control group is 114/114. In our point, both Saudi Arabia and Brazil have vast territories and long histories. Hence, maybe the ethnic origins are complex. And the lifestyles and customs may vary significantly across the two countries, respectively, which would contribute to great heterogeneity. What is more, the sample sizes of both studies are relatively smaller. Concluding from the results of subgroup analyses, the sample size, the source of controls and the genotyping method also influence the heterogeneity in a certain degree. Thus, more studies with large enough sample sizes and more detailed criteria are warranted. Lastly, published studies were included in our studies, whereas many other unpublished data were ignored. Therefore, potentially publication bias will exist in our study.

In summary, our meta‐analysis revealed the significant association between the CYP1A1 Ile462Val polymorphism and increased digest tract cancers risk. While no sufficient evidence was found to support the association between the CYP1A1 MspI polymorphism and DTC. In the subgroup analyses, the positive results were found in CC group, caucasians and mixed individuals for MspI polymorphism. Our results suggest that the CYP1A1 polymorphisms are potential risk factors for DTC. Large sample size and well‐designed studies with more clinical information like age, gender, smoking and drinking are needed to clarify our finding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author contribution

LJZ and YBH conceived and designed the study. HND and AJR performed the experiments. AJR, TTQ, QQW and DHZ analysed the data. AJR, TTQ, QQW and DHZ contributed to the reagents/materials/analysis tools. AJR wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with MspI polymorphism with adjusted OR and 95% CI (the codominant model CC versus TT).

Figure S2 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with Ile/Val polymorphism with adjusted OR and 95% CI (the codominant model GG versus AA).

Figure S3 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with MspI polymorphism after dropping the data from Saeed et al. 201324 (the dominant model CC + CT versus TT).

Figure S4 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with Ile/Val polymorphism after dropping the data from Pereira Serafim et al. 2008 47 (the dominant model GA+GG versus AA).

Table S1 Pooled ORs and 95% CIs of stratified meta‐analysis for MspI polymorphism.

Table S2 Pooled ORs and 95% CIs of stratified meta‐analysis for Ile/Val polymorphism.

Table S3 Heterogeneity test for MspI polymorphism.

Table S4 Heterogeneity test for Ile/Val polymorphism.

Table S5 Subgroup analyses for adjusted status (Yes or no) and adjusted status especially for smoking history (Yes or no) for Ile/Val polymorphism (GG/AA model).

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81472634) and Jiangsu Province Clinical Science and Technology Projects (Clinical Research Center, BL2012008).

References

- 1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015; 65: 87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peleteiro B, Castro C, Morais S, et al Worldwide burden of gastric cancer attributable to tobacco smoking in 2012 and predictions for 2020. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60: 2470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lakhoo K. Neonatal surgical conditions. Early Hum Dev. 2014; 90: 933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang JM, Cui XJ, Xia YQ, et al Correlation between TGF‐beta1‐509 C>T polymorphism and risk of digestive tract cancer in a meta‐analysis for 21,196 participants. Gene. 2012; 505: 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhu CL, Huang Q, Liu CH, et al NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) C609T gene polymorphism association with digestive tract cancer: a meta‐analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013; 14: 2349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yao L, Wang HC, Liu JZ, et al Quantitative assessment of the influence of cytochrome P450 2C19 gene polymorphisms and digestive tract cancer risk. Tumour Biol. 2013; 34: 3083–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang X, Zhang Y, Gu D, et al Increased risk of developing digestive tract cancer in subjects carrying the PLCE1 rs2274223 A>G polymorphism: evidence from a meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8: e76425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li P, Xu J, Shi Y, et al Association between zinc intake and risk of digestive tract cancers: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Nutr. 2014; 33: 415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu B, Liu K, Huang H, et al MspI and Ile462Val polymorphisms in CYP1A1 and overall cancer risk: a meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8: e85166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gong FF, Lu SS, Hu CY, et al Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) polymorphism and susceptibility to esophageal cancer: an updated meta‐analysis of 27 studies. Tumour Biol. 2014; 35: 10351–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu KT, Ge C, Xu XF, et al CYP1A1 polymorphism interactions with smoking status in oral cancer risk: evidence from epidemiological studies. Tumour Biol. 2014; 35: 11183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meng FD, Ma P, Sui CG, et al Association between cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) gene polymorphisms and the risk of renal cell carcinoma: a meta‐analysis. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Du H, Guo N, Shi B, et al The effect of XPD polymorphisms on digestive tract cancers risk: a meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9: e96301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu C, Jiang Z, Deng QX, et al Meta‐analysis of association studies of CYP1A1 genetic polymorphisms with digestive tract cancer susceptibility in Chinese. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014; 15: 4689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen B, Cao L, Yang P, et al Cyclin D1 (CCND1) G870A gene polymorphism is an ethnicity‐dependent risk factor for digestive tract cancers: a meta‐analysis comprising 20,271 subjects. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012; 36: 106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sivaraman L, Leatham MP, Yee J, et al CYP1A1 genetic polymorphisms and in situ colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1994; 54: 3692–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ye Z, Parry JM. Genetic polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 1A1, glutathione S‐transferase M1 and T1, and susceptibility to colon cancer. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 2002; 22: 385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma JX, Zhang KL, Liu X, et al Concurrent expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and CYP1A1 but not CYP1A1 MspI polymorphism is correlated with gastric cancers raised in Dalian. China. Cancer Lett. 2006; 240: 253–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Talseth BA, Meldrum C, Suchy J, et al Genetic polymorphisms in xenobiotic clearance genes and their influence on disease expression in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006; 15: 2307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luo YP, Chen HC, Khan MA, et al Genetic polymorphisms of metabolic enzymes‐CYP1A1, CYP2D6, GSTM1, and GSTT1, and gastric carcinoma susceptibility. Tumour Biol. 2011; 32: 215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Darazy M, Balbaa M, Mugharbil A, et al CYP1A1, CYP2E1, and GSTM1 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to colorectal and gastric cancer among Lebanese. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011; 15: 423–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rudolph A, Sainz J, Hein R, et al Modification of menopausal hormone therapy‐associated colorectal cancer risk by polymorphisms in sex steroid signaling, metabolism and transport related genes. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011; 18: 371–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ghoshal U, Tripathi S, Kumar S, et al Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP2E1 genes modulate susceptibility to gastric cancer in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastric Cancer. 2014; 17: 226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saeed HM, Alanazi MS, Nounou HA, et al Cytochrome P450 1A1, 2E1 and GSTM1 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to colorectal cancer in the Saudi population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013; 14: 3761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jain M, Kumar S, Ghoshal UC, et al CYP1A1 Msp1 T/C polymorphism in esophageal cancer: no association and risk modulation. Oncol Res. 2007; 16: 437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malik MA, Upadhyay R, Mittal RD, et al Association of xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes genetic polymorphisms with esophageal cancer in Kashmir Valley and influence of environmental factors. Nutr Cancer. 2010; 62: 734–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morita S, Yano M, Shiozaki H, et al CYP1A1, CYP2E1 and GSTM1 polymorphisms are not associated with susceptibility to squamous‐cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Int J Cancer. 1997; 71: 192–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nimura Y, Yokoyama S, Fujimori M, et al Genotyping of the CYP1A1 and GSTM1 genes in esophageal carcinoma patients with special reference to smoking. Cancer. 1997; 80: 852–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hori H, Kawano T, Endo M, et al Genetic polymorphisms of tobacco‐ and alcohol‐related metabolizing enzymes and human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma susceptibility. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997; 25: 568–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van Lieshout EM, Roelofs HM, Dekker S, et al Polymorphic expression of the glutathione S‐transferase P1 gene and its susceptibility to Barrett's esophagus and esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999; 59: 586–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang AH, Sun CS, Li LS, et al Relationship of tobacco smoking CYP1A1 GSTM1 gene polymorphism and esophageal cancer in Xi'an. World J Gastroenterol. 2002; 8: 49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu MT, Lee JM, Wu DC, et al Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P4501A1 and oesophageal squamous‐cell carcinoma in Taiwan. Br J Cancer. 2002; 87: 529–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang LD, Zheng S, Liu B, et al CYP1A1, GSTs and mEH polymorphisms and susceptibility to esophageal carcinoma: study of population from a high‐ incidence area in north China. World J Gastroenterol. 2003; 9: 1394–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang AH, Sun CS, Li LS, et al Genetic susceptibility and environmental factors of esophageal cancer in Xi'an. World J Gastroenterol. 2004; 10: 940–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abbas A, Delvinquiere K, Lechevrel M, et al GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1 and CYP1A1 genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to esophageal cancer in a French population: different pattern of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004; 10: 3389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang D, Su M, Tian D, et al Associations between CYP1A1 and CYP2E1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to esophageal cancer in Chaoshan and Taihang areas of China. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012; 36: 276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yun YX, Wang YP, Wang P, et al CYP1A1 genetic polymorphisms and risk for esophageal cancer: a case‐control study in central China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014; 14: 6507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kiss I, Sandor J, Pajkos G, et al Colorectal cancer risk in relation to genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 1A1, 2E1, and glutathione‐S‐transferase M1 enzymes. Anticancer Res. 2000; 20: 519–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suzuki S, Muroishi Y, Nakanishi I, et al Relationship between genetic polymorphisms of drug‐metabolizing enzymes (CYP1A1, CYP2E1, GSTM1, and NAT2), drinking habits, histological subtypes, and p53 gene point mutations in Japanese patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2004; 39: 220–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Slattery ML, Samowtiz W, Ma K, et al CYP1A1, cigarette smoking, and colon and rectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 160: 842–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li H, Chen XL, Li HQ. Polymorphism of CYPIA1 and GSTM1 genes associated with susceptibility of gastric cancer in Shandong Province of China. World J Gastroenterol. 2005; 11: 5757–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen J, Wang RT, Xu YC, et al Interaction models of CYP1A1, GSTM1 polymorphisms and tobacco smoking in intestinal gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005; 11: 6056–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Little J, Sharp L, Masson LF, et al Colorectal cancer and genetic polymorphisms of CYP1A1, GSTM1 and GSTT1: a case‐control study in the Grampian region of Scotland. Int J Cancer. 2006; 119: 2155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Agudo A, Sala N, Pera G, et al Polymorphisms in metabolic genes related to tobacco smoke and the risk of gastric cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006; 15: 2427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yeh CC, Sung FC, Tang R, et al Association between polymorphisms of biotransformation and DNA‐repair genes and risk of colorectal cancer in Taiwan. J Biomed Sci. 2007; 14: 183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yoshida K, Osawa K, Kasahara M, et al Association of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, GSTM1 and NAT2 gene polymorphisms with colorectal cancer and smoking. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007; 8: 438–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pereira Serafim PV, Cotrim Guerreiro da Silva ID, Manoukias Forones N. Relationship between genetic polymorphism of CYP1A1 at codon 462 (Ile462Val) in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2008; 23: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kobayashi M, Otani T, Iwasaki M, et al Association between dietary heterocyclic amine levels, genetic polymorphisms of NAT2, CYP1A1, and CYP1A2 and risk of colorectal cancer: a hospital‐based case‐control study in Japan. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009; 44: 952–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kobayashi M, Otani T, Iwasaki M, et al Association between dietary heterocyclic amine levels, genetic polymorphisms of NAT2, CYP1A1, and CYP1A2 and risk of stomach cancer: a hospital‐based case‐control study in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2009; 12: 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nisa H, Kono S, Yin G, et al Cigarette smoking, genetic polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: the Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study. BMC Cancer. 2010; 10: 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cleary SP, Cotterchio M, Shi E, et al Cigarette smoking, genetic variants in carcinogen‐metabolizing enzymes, and colorectal cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2010; 172: 1000–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malik MA, Upadhyay R, Mittal RD, et al Role of xenobiotic‐metabolizing enzyme gene polymorphisms and interactions with environmental factors in susceptibility to gastric cancer in Kashmir Valley. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2009; 40: 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with MspI polymorphism with adjusted OR and 95% CI (the codominant model CC versus TT).

Figure S2 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with Ile/Val polymorphism with adjusted OR and 95% CI (the codominant model GG versus AA).

Figure S3 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with MspI polymorphism after dropping the data from Saeed et al. 201324 (the dominant model CC + CT versus TT).

Figure S4 Forest plot of digestive cancer risk associated with Ile/Val polymorphism after dropping the data from Pereira Serafim et al. 2008 47 (the dominant model GA+GG versus AA).

Table S1 Pooled ORs and 95% CIs of stratified meta‐analysis for MspI polymorphism.

Table S2 Pooled ORs and 95% CIs of stratified meta‐analysis for Ile/Val polymorphism.

Table S3 Heterogeneity test for MspI polymorphism.

Table S4 Heterogeneity test for Ile/Val polymorphism.

Table S5 Subgroup analyses for adjusted status (Yes or no) and adjusted status especially for smoking history (Yes or no) for Ile/Val polymorphism (GG/AA model).