Synopsis

The 2013 decision of the American Medical Association (AMA) to recognize obesity as a complex, chronic disease that requires medical attention came as the result of developments over three decades. Defining a condition such as obesity to be a disease is a very public process that is largely driven by expectation of costs and benefits. Although the public has been slow to embrace defining obesity as a purely medical condition, evidence is emerging for broader awareness of factors beyond personal choice influencing obesity. The AMA decision appears to be working in concert with other factors to bring more access to care, less blame for people with the condition, and more favorable conditions for research to identify effective strategies for prevention and clinical care to reduce the impact of this disease.

Keywords: Obesity, health policy, chronic disease, health care economics and organizations, medicalization, access to healthcare, social stigma

Introduction

Perhaps because of the close relationship among physical appearance and obesity, intertwined with moral beliefs and class discriminations related to obesity, the social and cultural implications of excess weight have historically received more attention than its medical implications. Until the mid to late twentieth century in America, undernourishment and hunger were prioritized as more important public health concerns than was obesity. In 1950, the first medical society devoted to clinical management of obesity established itself as the National Obesity Society. The organization subsequently changed its name to the National Glandular Society, the American College of Endocrinology and Nutrition, the American Society of Bariatrics, the American Society of Bariatric Physicians, and now the Obesity Medicine Association.1

With the recognition that obesity is responsible for a growing prevalence chronic diseases, obesity has come to be regarded as “the single greatest threat to public health for this century.”2 Research has provided a deeper understanding of the genetic, metabolic, environmental, and behavioral factors that contribute to obesity. This growing evidence base challenges the dominant public understanding of obesity as a reversible condition resulting primarily from dietary and lifestyle choices that reflect ignorance or limited motivation.

These developments have led obesity to be increasingly described by scientific and medical experts as a complex chronic disease. This paper will review reasons why obesity is regarded as a disease and implications of this increasingly dominant perspective.

Defining What Is a Disease

In 2008, the Obesity Society commissioned a panel of experts to consider the question of labeling obesity a disease and to complete a thorough review of pertinent evidence and arguments.3 The panel considered three distinct approaches to the question:

Scientific. This approach hinges upon two questions. What are the characteristics that define a disease? And what is the evidence that obesity possesses those characteristics? The panel found that the scientific approach was inadequate for answering this question “because of a lack of a clear, specific, widely accepted, and scientifically applicable definition of ‘disease.’”

Forensic. This approach relies upon authoritative statements from respected organizations declaring that obesity is or should be considered to be a disease. After an exhaustive search of public statements, the panel found “is a clear and strong majority leaning – although not complete consensus – toward obesity being a disease.” However they found that these statements were largely issued as a matter of opinion and lacked arguments or evidence to support a determination of “what is true or what is right.”

Utilitarian. This third approach – a logical analysis of the benefits and harms arising from considering obesity a disease – formed the basis for the panel’s ultimate recommendation.

It follows that the determination of what is a disease is more of a social and policy determination than it is a scientific determination. Policymakers and experts make reasoned judgments about whether or not a condition should be considered a disease based upon evidence, as well as explicit and implicit values. Public acceptance of that judgment (or not) represents a final step in this process. Randolph Neese summarized the inherent challenge of defining whether something is a disease:

Our social definition of disease will remain contentious, however, because values vary, and because the label “disease” changes judgments about the moral status of people with various conditions, and their rights to medical and social resources.4

Milestones in Regarding Obesity as a Disease and their Policy Implications

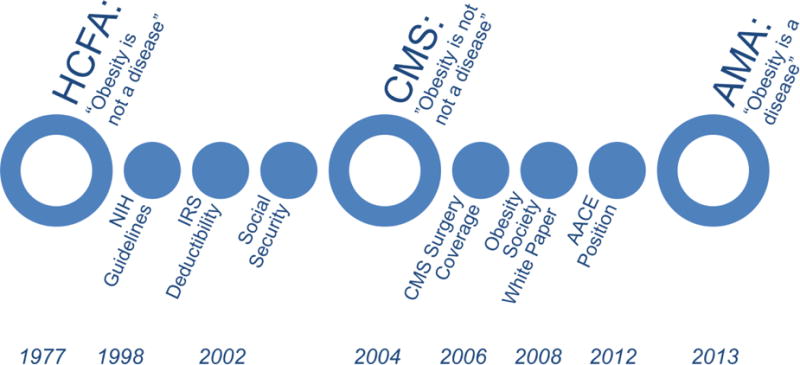

Figure 1 depicts milestones in regarding obesity as a disease. Each milestone is an example of how labeling a condition as a “disease” or “not a disease” can have significant policy implications. Established in 1977, the Healthcare Financing Administration (HCFA, predecessor to CMS, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) included language in its Coverage Issues Manual stating that “obesity is not an illness.”5 This language reflected widely-held beliefs and served as a model for denying coverage of obesity care under both publicly and privately funded health plans.

Figure 1. Milestones toward Considering Obesity to Be a Disease.

Large open circles represent key milestones; smaller circles represent other noteworthy milestones.

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health published Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults that stated, “Obesity is a complex multifactorial chronic disease.”6

In early 2002, the Internal Revenue Service issued a ruling that expenses for obesity treatment would qualify as deductible medical expenses.7 Later in 2002, the Social Security Administration (SSA) published an evaluation of obesity stating that “Obesity is a complex, chronic disease characterized by excessive accumulation of body fat.”8 This determination explicitly stated that obesity is a valid medical source of impairment for the purpose of evaluating Social Security disability claims.

A key milestone came in 2004 when CMS removed language stating that “obesity is not an illness” from its Coverage Issues Manual.5 Although this action did not include a specific determination that obesity is a disease, it removed a significant obstacle to further progress and coverage for obesity-related medical services.

In 2006, CMS issued a National Coverage Determination providing coverage for bariatric surgery under Medicare, a decision that followed as a natural consequence of the agency’s 2004 reassessment of obesity.9

As previously mentioned, the Obesity Society published a white paper on evidence and arguments for obesity as a disease in 2008, followed in 2012 by a similar position from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.10

Finally, in 2013, the American Medical Association resolved at its annual House of Delegates meeting to “recognize obesity as a disease state with multiple pathophysiological aspects requiring a range of interventions to advance obesity treatment and prevention.”11 Though this resolution has no legal standing, the AMA has stated that “recognizing obesity as a disease will help change the way the medical community tackles this complex issue.” Their leadership in shifting the care model for obesity to a chronic disease model may have a significant impact on the way obesity is addressed, as discussed below.

Initial Public Response to the AMA Decision

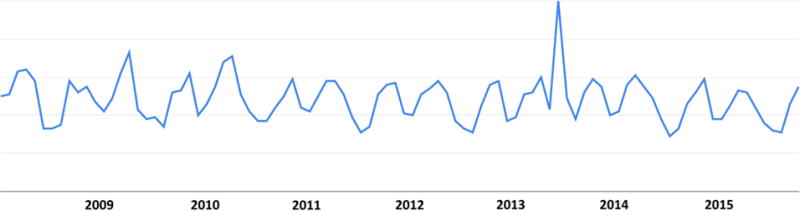

The AMA decision to recognize obesity as a disease captured considerable public attention in June of 2013 when it was announced. Though it continued to be discussed and debated among stakeholders in health and obesity policy, interest from the general public quickly faded, as indicated by Figure 2, which depicts Google Trends data for Internet search volume related to obesity and disease.

Figure 2. Interest over Time in “Obesity Disease”.

The vertical axis is an index of the relative popularity (measured by number of searches) for the search term (obesity disease), compared to all Internet searches completed on Google at a given time. Source: Google Trends Internet Search Index.

Much of the public debate about the merits of this decision included three distinct viewpoints:

Relief and Agreement. Clinicians, researchers, and individuals with obesity expressed relief that obesity was now being seen as a legitimate health concern, rather than a cosmetic or lifestyle concern. Sarah Bramblette expressed this perspective in Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics (NIB): “I celebrated the American Medical Association’s classification of obesity as a disease…I am a real person and deserve the same level of access to healthcare as other patients.”12

Concern about Weight Discrimination. Activists in the Fat Acceptance and Health at Every Size movements have consistently expressed opposition to this decision, anticipating that its primary effect would be to promote size and weight discrimination. In another NIB essay, Jennifer Hansen expressed this view: “Classifying obesity as a disease provides more ammunition for the ‘war on obesity.’ From a fat person’s perspective, the ‘war on obesity’ is a war on fat people.”13

Concern about Personal Responsibility. Michael Tanner captured this perspective in the National Review: “At first glance, it’s a minor story, hardly worth mentioning, but in reality the AMA’s move is a symptom of a disease that is seriously troubling our society: the abdication of personal responsibility and an invitation to government meddling.”14

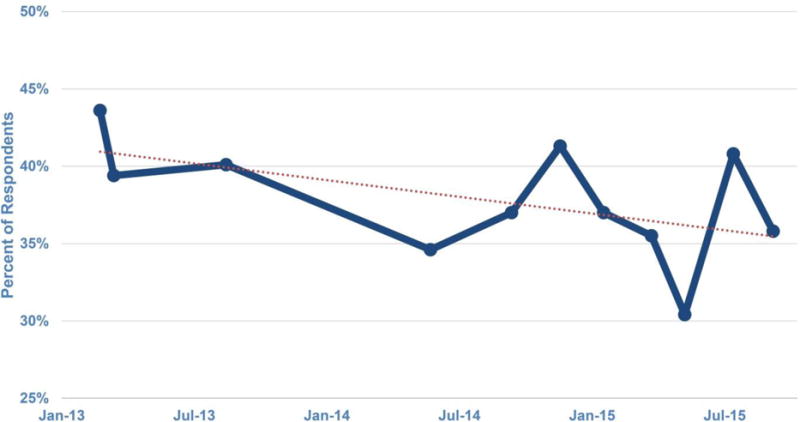

Research on public perception of obesity following the AMA decision suggests a shift away from the dominant view that obesity is a personal problem of bad choices (Figure 3). However, this research does not suggest that the public is increasingly adopting the view that obesity is a medical problem. Rather, the public is shifting toward a view that obesity is a community problem of bad food and inactivity.15

Figure 3. Trend in Public Perception that Obesity Is a “Personal Problem of Bad Choces”.

Between Feb 2013 and Mar 2015, the proportion of the public that views obesity primarily as a “personal problem of bad choices” declined modestly (p=0.0004, binomial regression) from 44% to 36%. Adapted from Kyle et al.15

These findings are generally consistent with observations by Puhl et al. that public awareness of the AMA decision is relatively low. Nonetheless, their study documented more public agreement with statements in support of describing obesity as a disease than with statements opposing it.16

Potential Effects of Regarding Obesity as a Disease

In the 2008 white paper commissioned by the Obesity Society, the authors concluded:

Considering obesity a disease is likely to have far more positive than negative consequences and to benefit the greater good by soliciting more resources into research, prevention, and treatment of obesity; by encouraging more high-quality caring professionals to view treating the obese patient as a vocation worthy of effort and respect; and by reducing the stigma and discrimination heaped upon many obese persons.

Two years after the decision by AMA to recognize obesity as a disease, assessing the effects of that decision against expectations is a worthwhile exercise, albeit one that involves a substantial degree of subjective judgments. Certainly, many factors are at work in changes observed since the AMA decision.

Public understanding of obesity has arguably improved, as measured by a decline in the dominant view that obesity is simply a personal problem of bad choices. Likewise, the research of Puhl and Liu suggests that the public is more supportive of this view of obesity than opposed to it.16 Still, public opinion is more focused on risk factors related to the food supply and physical activity than on the medical aspects of obesity.15 This may be a reflection of the complexity of a disease that remains a challenge to both researchers and healthcare professionals.

Stigma is a prevalent problem for people living with obesity17 and the evidence for any changes in this phenomenon is mixed. One manifestation of stigma is the idea that “fat shaming”, or shaming people with obesity about their weight, will help the individual lose weight. This approach has received considerable attention in popular media and online social networks in the years since AMA designated obesity as a disease. Fat shaming was hardly recognized before 2012, but interest in the subject has grown dramatically. Assigning the label of “fat shaming” to this idea inherently positions explicit bias against people with obesity as socially unacceptable.

While explicit shaming of people with obesity may be increasingly rejected, it is not clear that the prevalence of weight bias is changing. In fact, research by the Obesity Action Coalition finds increasing social discomfort with people who have obesity.15

Prevention efforts might best be described as experiencing no discernible change in the two years since the AMA decision. Writing in Lancet this year, Roberto et al. describe “patchy progress” in obesity prevention with only “isolated areas of improvement.”18

Experimental data published in 2014 suggested that describing obesity as a disease could undermine prevention efforts through a negative effect on self-regulation of dietary behavior.19

Treatment options for obesity have expanded significantly, with the introduction of four new drugs and three devices. FDA has developed a more explicit framework for evaluating benefit/risk tradeoffs for new obesity treatments.20 Research on new treatment options appears to be growing and multiple national health organizations are working together on guidelines and advocacy for obesity care.21

Insurance reimbursement remains a significant problem for both patients and providers in obesity care. Nonetheless, some changes have occurred that will influence coverage for obesity care. In 2014, the federal Office of Personnel Management issued guidance to health plans for federal employers that they could no longer exclude obesity care by characterizing obesity as a lifestyle or cosmetic condition. In 2015 the National Conference of Insurance Legislators resolved that state legislatures should provide for “coverage of the full range of obesity treatment.”22

Medical education has received significant attention from the Bipartisan Policy Center in a report issued in June 2014.23 In addition, work of the Obesity Society to identify gaps in testing for obesity-related competencies on medical board examinations has resulted in a commitment to address the gaps.24 Finally, although it has not yet passed, legislation entitled the ENRICH ACT has been introduced to provide grants to medical schools for incorporating obesity education into their curriculum.25

Consumer protection against fraudulent weight loss products remains a significant problem. Noteworthy actions against dietary supplements by state attorneys general and the U.S. Justice Department have been taken in the last year.26 The Obesity Society, the Obesity Medicine Association, the Obesity Action Coalition, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recently issued a joint position calling for more stringent regulation of dietary supplements that make therapeutic claims for obesity.27

Discrimination in employment has received increased attention following the AMA decision. Employment law firms have issued opinions that this ruling could create additional risk for employers who discriminate against people with obesity, and the EEOC has won additional rulings that obesity can be considered a protected disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act.28

Credibility of obesity research and care is difficult to observe directly. It is worth noting that the numbers of physicians taking the certification examination of the American Board of Obesity Medicine has grown dramatically in the years since the AMA decision. The number applying to take the exam in 2015 grew by 27%, which might be taken as evidence of growing credibility for the emerging specialty of obesity medicine.29 In addition, the Commission on Dietetic Registration is preparing to offer a certification examination in obesity and weight management for allied health professionals.30

Implications for Obesity Research

The National Institutes of Health has recognized that obesity is a chronic disease since 1998, and this is reflected in the Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research released by the NIH Obesity Task Force in 2011.31 The main highlights of the research agenda outlined include a need for more probative research to better understand the fundamental causes of obesity, to develop new and more effective treatments for obesity, to empirically test strategies for obesity prevention in the real-world settings for which they are intended, and to improve technology to overcome many challenges in obesity research. This agenda demonstrates acknowledgement of a chronic and relatively unaddressed disease that is still in great need of further probative research to improve outcomes.

However, whether or not progress is being made on this probative research agenda, and if the AMA decision to recognize obesity as a disease has influenced the research agenda and resources for obesity research thus far, is unclear. Ultimately, this research agenda demonstrates insightful leadership and is well informed, but will not influence which research is conducted until individuals participating in the grant review process view obesity as a disease.

If strides in the medicalization of obesity treatment through improved education in medical schools and insurance coverage of treatments following the decision continue to progress, this may eventually lead to more demand for, and better coordination of, data collection on evidence-based care models. Similarly, if the disease decision continues to lessen the view that obesity is an issue of personal responsibility, this may eventually be reflected in the treatment and prevention approaches that are being pursued through research.

Summary

Defining what is and is not a disease is necessarily a pragmatic decision. A clear, objective, and widely accepted definition of what is and is not a disease – one that adequately captures things conventionally accepted as diseases and excludes things that are not – is lacking. Obesity is a highly stigmatized condition that has long been generally regarded by the public as a reversible consequence of personal choices. As research has documented the genetic, biological, and environmental factors that play important roles in obesity and its resistance to treatment, a growing number of medical and scientific organizations have come to regard obesity as a disease. The decision by the American Medical Association (AMA) in 2013 to recognize obesity as a disease state marked a key milestone in progress toward accepting obesity as a disease and advancing evidence-based approaches for its prevention and treatment. Some signs of progress are evident following the AMA decision, although diverse stakeholders continue to debate the merits of this determination.

Key Points.

Defining what is and is not a disease is fundamentally a pragmatic decision. A clear, objective, and widely accepted definition of what is and is not a disease – a definition that adequately captures things that conventionally accepted as diseases and excludes things that are conventionally not – is lacking.

Obesity is a highly stigmatized condition that has long been generally regarded by the public as a reversible consequence of personal choices.

As research has documented the genetic, biological, and environmental factors that play important roles in obesity and its resistance to treatment, a growing number of medical and scientific organizations have come to regard obesity as a disease.

The decision by the American Medical Association (AMA) in 2013 to recognize obesity as a disease state marked a key milestone in progress toward accepting obesity as a disease and advancing evidence-based approaches for its prevention and treatment.

Some signs of progress are evident following the AMA decision, although diverse stakeholders continue to debate the merits of this determination.

Contributor Information

Theodore K. Kyle, Email: ted.kyle@conscienhealth.org, ConscienHealth, 2270 Country Club Drive, Pittsburgh, PA 15241; 412-205-9303.

Emily J. Dhurandhar, Email: emily.dhurandhar@ttu.edu, Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, Box 43011, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-3011; 806-834-6556.

David B. Allison, Email: dallison@uab.edu, Office of Energetics, Nutrition Obesity Research Center, and Department of Biostatistics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Ryals Building, Room 140J, 1665 University Boulevard, Birmingham, AL 35294; 205-975-9167.

References

- 1.Eknoyan G. A history of obesity, or how what was good became ugly and then bad. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2006;13(4):421–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison DB, Downey M, Atkinson RL, et al. Obesity as a disease: a white paper on evidence and arguments commissioned by the Council of the Obesity Society. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(6):1161–77. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nesse RM. On the difficulty of defining disease: a Darwinian perspective. Med Health Care Philos. 2001;4(1):37–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1009938513897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tillman K. National Coverage Analysis (NCA) Tracking Sheet for Obesity as an Illness (CAG-00108N) CMS.gov. 2004 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-tracking-sheet.aspx?NCAId=57&TAId=23&IsPopup=y&bc=AAAAAAAAAgAAAA%3D%3D&. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 6.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. (NIH publication 98-4083).The Evidence Report. 1998 Sep; http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.pdf.

- 7.Anderson C. Obesity Is Tax Deductible. CBSnews.com. 2002 Available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/obesity-is-tax-deductible/. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 8.SSA.gov. Social Security Administration Program Operations Manual (POMS) - DI 24570.001 Evaluation of Obesity. 2002 Available at: https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0424570001. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 9.Phurrough S, Salive M. Decision Memo for Bariatric Surgery for the Treatment of Morbid Obesity (CAG-00250R) CMS.gov. 2006 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=160&ver=32&NcaName=Bariatric+Surgery+for+the+Treatment+of+Morbid+Obesity+(1st+Recon)&bc=BEAAAAAAEAgA. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 10.Mechanick JI, Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Garvey WT. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ position statement on obesity and obesity medicine. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(5):642–8. doi: 10.4158/EP12160.PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollack A. AMA Recognizes Obesity as a Disease. NYTimescom. 2013 Available at: http://nyti.ms/1Guko03. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 12.Bramblette S. I am not obese. I am just fat. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2014;4(2):85–8. doi: 10.1353/nib.2014.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen J. Explode and die! A fat woman’s perspective on prenatal care and the fat panic epidemic. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2014;4(2):99–101. doi: 10.1353/nib.2014.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanner M. Obesity Is Not a Disease. National Review Online. 2013 Available at: http://www.nationalreview.com/article/352626/obesity-not-disease-michael-tanner. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 15.Kyle T, Thomas D, Ivanescu A, et al. Indications of Increasing Social Rejection Related to Weight Bias. Presented at: ObesityWeek; November 2, 2015; Los Angeles, CA. Available at: http://conscienhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Bias-Study-Report.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puhl RM, Liu S. A national survey of public views about the classification of obesity as a disease. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(6):1288–95. doi: 10.1002/oby.21068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puhl R, Kyle T. Pervasive Bias: An Obstacle to Obesity Solutions. National Academy of Medicine. 2014 Available at: http://nam.edu/perspectives-2015-pervasive-bias-an-obstacle-to-obesity-solutions/. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 18.Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes C, et al. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2400–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61744-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoyt CL, Burnette JL, Auster-gussman L. “Obesity is a disease”: examining the self-regulatory impact of this public-health message. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(4):997–1002. doi: 10.1177/0956797613516981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho MP, Gonzalez JM, Lerner HP, et al. Incorporating patient-preference evidence into regulatory decision making. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(10):2984–93. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-4044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith S. AMA Joins Call for Coverage of Obesity Treatments and Medications - TOS Connect. The Obesity Society. 2014 Available at: http://tosconnect.obesity.org/news/press-releases/new-item2. Accessed November 21, 2015.

- 22.National Conference of Insurance Legislators. NCOIL Legislotors Adopt Resolution Encouraging Coverage For Obesity Treatment. 2015 Available at: http://www.ncoil.org/HomePage/2015/07292015ObesityResolutionPR.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 23.Glickman D, Shalala D. Teaching Nutrition And Physical Activity In Medical School: Training Doctors For Prevention-Oriented Care. Washington, DC: Bipartisan Policy Center; 2014. Available at: http://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/Med_Ed_Report.PDF. Accessed November 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kushner R, Butsch S, Aronne L, et al. Review of Obesity-Related Items on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Examinations for Medical Students: What is Being Tested?. Presented at: ObesityWeek; November 2, 2015; Los Angeles, CA. Available at: https://guidebook.com/guide/48144/poi/4317961/?pcat=185403. Accessed November 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glickman D, Shalala D. The ENRICH Act will provide better tools to fight obesity epidemic. TheHill. 2015 Available at: http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/healthcare/236479-the-enrich-act-will-provide-better-tools-to-fight-obesity. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 26.Lorenzetti L. Justice Department Charges Dietary Supplements Maker. Fortune. 2015 Available at: http://fortune.com/2015/11/17/doj-dietary-supplements/. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 27.The Obesity Society. Dietary Supplements Sold as Medicinal or Curative for Obesity. 2015 Available at: http://www.obesity.org/publications/position-and-policies/medicinal-or-curative. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 28.Katz D. Another Judge Finds that Obesity May be a “Disability” Under the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) The National Law Review. 2015 Available at: http://www.natlawreview.com/article/another-judge-finds-obesity-may-be-disability-under-ada-americans-disabilities-act. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 29.Burke J. Record Number of Physicians to Sit for 2015 ABOM Exam. American Board of Obesity Medicine. 2015 Available at: http://abom.org/record-number-of-physicians-to-sit-for-2015-abom-exam/. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 30.Commission on Dietetic Registration. CDR’s New Interdisciplinary Certification in Obesity and Weight Management. 2015 Available at: https://www.cdrnet.org/interdisciplinary. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 31.17.; NIH Obesity Research. Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research. 2011 Available at: http://obesityresearch.nih.gov/about/strategic-plan.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2015.