ABSTRACT

There is increasing evidence for a role of early life gut microbiota in later development of asthma in children. In our recent study, children with reduced abundance of the bacterial genera Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium, and Rothia had an increased risk of development of asthma and addition of these bacteria in a humanized mouse model reduced airway inflammation. In this Addendum, we provide additional data on the use of a humanized gut microbiota mouse model to study the development of asthma in children, highlighting the differences in immune development between germ-free mice colonized with human microbes compared to those colonized with mouse gut microbiota. We also demonstrate that there is no association between the composition of the gut microbiota in older children and the diagnosis of asthma, further suggesting the importance of the gut microbiota-immune system axis in the first 3 months of life.

KEYWORDS: asthma, germ-free mice, gut microbiota, infants, lung

Importance of the early infant gut microbiota on development of childhood asthma

Prevalence of childhood asthma has steadily increased over the last 2 decades globally propelling it to the most prevalent childhood disease in high income countries.1 This cannot be explained by genetic differences alone, given the rapid increase in prevalence. Attention has therefore focused on environmental influences, which may be amenable to modification. A number of studies have demonstrated a link between asthma and early-life exposures, which perturb the normal infant microbiota. These include use of pre- and perinatal antibiotics, delivery by caesarean section (vs vaginal), urban living (vs farm living), dogs as pets, and formula feeding.2 Recent studies have suggested that an early-life critical window exists, whereby any change in the microbiota has a significant impact on immune development.3-5

We recently showed that reduction in 4 bacterial genera – Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium and Rothia – in the gut microbiota of infants at 3 months of age was associated with an increased risk of developing childhood asthma, and these differences were not observed at one year of age.6 In addition to identifying this disparity in bacterial composition of the gut microbiota, we confirmed a functional difference with significantly lower levels of fecal acetate and higher levels of urine urobilinogen in children with an increased risk of developing asthma. Finally we demonstrated a causal relationship between these 4 genera and asthma development in a mouse model, leading to the exciting prospect of an early diagnostic tool for asthma in infants and the potential to intervene at this young age to prevent the later development of asthma.

In this Addendum, we explore further use of the humanized microbiota mouse model, providing additional data to confirm its validity in these studies. In addition we examine the importance of this early infant ‘window of opportunity' by investigating a cohort of school-aged children with asthma and atopy, given that the original study only considered children up to 1 y of age.

A humanized mouse gut microbiota model

Development of a suitable experimental animal model is pivotal to address proof-of-mechanism studies exploring the microbiota-host interaction, and enable intervention studies that may not be feasible in human subjects. Germ-free (GF) mice are ideal for such studies, as they have no prior exposure to microbes and allow control of other influences of their microbiota, such as host genotype, diet and housing conditions. One option would be to introduce mouse-derived gut microbiota into such GF mice, since previous studies have shown that a host-specific microbiota appears to be critical for development of a healthy immune system.7 The disadvantage of this approach, however, is that many bacterial genera and species found in mice are not observed in humans,8 with the most notable differences in the abundance of Firmicutes7 – a major component of the infant microbiota. This makes it difficult to extrapolate from these studies to what may happen in humans. Humanized mouse gut microbiome models have previously been developed, with successful transplant of a significant proportion of the human microbiota.9,10 These transplanted microbial communities were stable and transmitted vertically across generations, but have not been used to investigate resultant effects on airway inflammation.

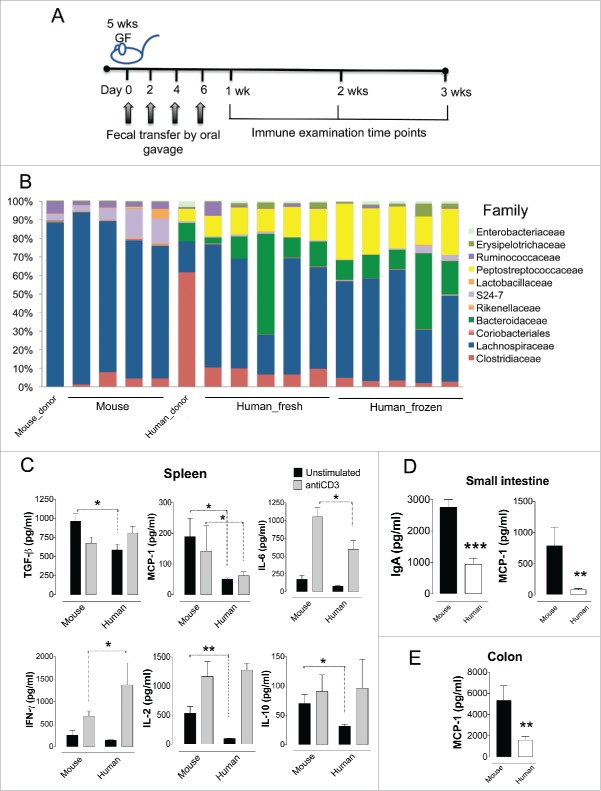

In order to develop a human microbiota mouse model to study development of asthma, we inoculated outbred GF Swiss Webster mice with gut microbiota from mouse and human donors and investigated immune development over the following 3 weeks (Fig. 1A). The microbial composition of the mouse donor was dominated by Lachnospiraceae, with smaller numbers of Ruminococcaceae and S24-7 (an uncultured lineage of Bacteroidetes) which was reflected in the recipient mice (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the human donor had higher number of family-level taxa of high abundance (>2 %), including significant proportions of Clostridiaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Bacteroidaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. These taxa were transferred to the mouse recipients, with notable presence of Bacteroidaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae, which were absent when mouse stool donors were used (Fig. 1B). However, members of the Clostridiaceae family did not predominate in the recipient mice as they did in the human donor microbiota, suggesting that the ability of some bacterial taxa to flourish in the gut is specific to the host species and/or diet. There were no significant differences in α-diversity between the mice that received human or murine microbiota. In addition, there were no significant differences between the use of fresh and frozen feces. This confirms the findings from previous studies7,9-11 that a remarkable proportion of the human microbiota can be transplanted into GF mice, enabling detailed study of the influences of the gut microbiota on the host. The successful use of frozen feces (which can be stored for long periods of times) makes collection and processing of human fecal samples in clinical studies substantially easier, broadening the potential use of this humanized mouse model.

Figure 1.

Germ-free mice adopt a large proportion of human fecal microbiota with a subsequent decrease in local and systemic immune response. (A) Inoculation scheme of 5-week-old Swiss Webster germ-free mice with a fecal slurry from a mouse or an infant human (Nmouse = 4, Nhuman fresh = 5, Nhuman frozen = 5). Subgroups of mice were examined for immune effects at 1, 2 and 3 weeks post initial gavage with the fecal slurry. (B) Family-level relative abundance of microbial taxa in the donor mouse feces (Mouse_donor), the human one-year-old donor (Human_donor), and the feces from the recipient mice that were inoculated with murine (Mouse) or human (Human) feces, 3 weeks after first gavage. The human fecal sample was given fresh (Human_fresh) or frozen (Human_frozen). (C) Splenocyte cytokine production after cultured with anti-CD3 to stimulate lymphocyte proliferation (gray bars) or unstimulated (black bars). Bars represent the average of triplicate wells. (D) IgA and MCP-1 production in the supernatant of small intestinal tissue explants from mice inoculated with murine (black bars) or human (white bars) feces. (E) MCP-1 production in the supernatant of colonic tissue explants from mice inoculated with murine (black bars) or human (white bars). C-E) All cytokine and IgA measurements were done one week after the initial inoculum. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Reduced immune responses occur in the humanized mouse

The mammalian gut microbiota is a very complex system which has co-evolved with the host immune system.12 Gut bacteria have a key role in immune development and immune function via production of bile acids, short chain fatty acids, vitamins and amino acids and regulation of lipid homeostasis.13 If a humanized mouse gut microbiota model is to be successfully used to investigate the microbiota-immune system axis, it is vital to understand the immunological effects of transplanting human feces into GF mice. A panel of 14 cytokines and IgA levels were therefore analyzed in cultured spleen, small intestine and colonic tissue from mice that had received feces from other mice or from humans (Fig. 1C–E). There were no differences found for the majority of cytokines measured, but splenocytes produced significantly lower TGF-β, MCP-1, IL-6, IL-2 and IL-10 and increased IFN-γ following inoculation with human feces compared with mouse feces (ANOVA, p < 0.05). The reduction in MCP-1 was also observed in tissue from both small intestine and the colon (Student t-test, p < 0.01), with significantly decreased IgA levels (Student t-test, p < 0.001) also noted in the small intestine from human donor mice.

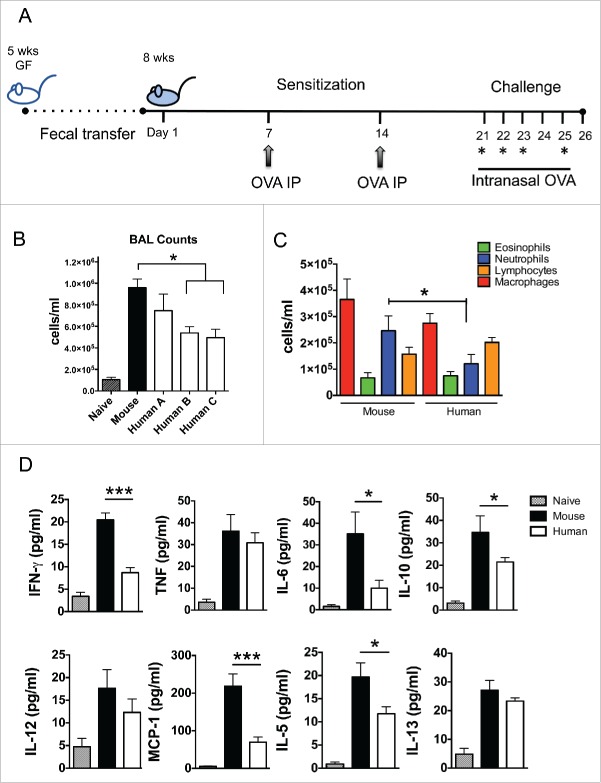

This suggests that human microbiota colonized mice have reduced immune responses compared to mouse microbiota colonized mice. This is consistent with a previous study which found reduced levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, fewer proliferating T cells, fewer dendritic cells and low antimicrobial peptide expression in human microbiota colonized mice, resembling more responses in GF mice.7 In this previous study, inoculating human microbiota colonized mice with segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) partially restored T cell numbers, suggesting that SFB were at least partially responsible for optimal immune development. Histological examination of the ileal mucosa in our study demonstrated segmented bacilli in close proximity to the epithelium of mice colonized with mouse microbiota, but not human microbiota; however, there were no significant histological differences found between the 2 groups in terms of gut architecture (Fig. 2). Although we were unable to confirm if these segmented bacilli were definitely SFB, this further highlights the importance of species-specific microbiota in host immune development.

Figure 2.

Intestinal colonization of germ-free mice with human microbiota leads to decreased adherent bacteria in the ileum. Representative histological findings in the ileal mucosa of mice colonized with murine (A) or human (B) microbiota. (A) Bacilli were noticeably present in close proximity to the ileal epithelium of mice colonized with murine microbiota. Increased magnification evidenced segmented bacilli attached to the tip of a villus (arrow). (B) Very few or no bacteria were observed in close proximity to the ileal mucosa of mice colonized with human microbiota.

Ovalbumin-induced lung inflammation in germ-free mice

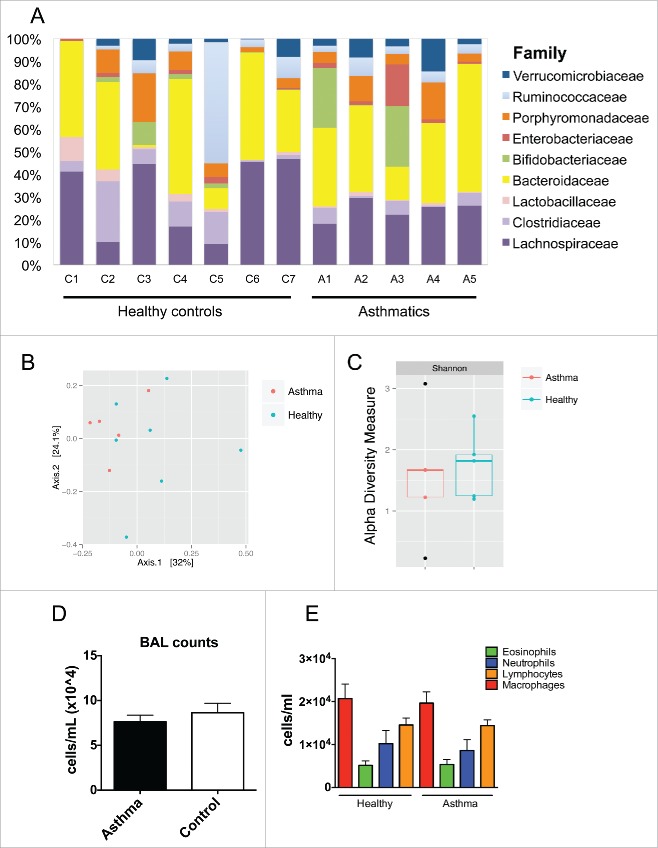

The reduction in a number of cytokines involved in Th1, Th2 and regulatory T cell responses in the spleens of GF mice colonized with human microbiota suggested that it could be difficult to identify any impact on lung inflammation in this model. To test this, we used a mouse model of airway inflammation based on peritoneal sensitization and intranasal challenge with ovalbumin (OVA) to examine if a humanized microbiota mouse model mounted a measurable lung immune response (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Intestinal colonization with human microbiota leads to decreased lung inflammation upon OVA challenge. (A) OVA model of experimental murine lung inflammation. Mice previously colonized with human or murine microbiota were sensitized systemically and subsequently challenged intranasally with OVA, over the course of 25 d. (B) Total cellular infiltrates from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of mice colonized with murine fecal microbiota or with feces from 3 healthy children (Human A, B, C), and challenged with OVA or PBS (Naïve) (Nhuman = 13, Nmouse = 5, Nnaive = 4). (C) Differential leukocyte counts from BALs of mice colonized with murine or human microbiota (all human microbiota-colonized mice were pooled). (D) Cytokine determination in lung homogenates from mice colonized with murine (black bars) or human (white bars) microbiota and challenged with OVA or PBS (Naïve; gray bars). * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

Recipients of human microbiota had reduced lung cellular infiltrates compared to recipients of mouse microbiota (ANOVA, p < 0.05), although they were still significantly higher than naïve (non OVA-sensitized) mice (Fig. 3B). This moderate reduction in inflammatory cells was due predominantly to a reduction in neutrophils (ANOVA, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3C). Analysis of cytokine profiles from lung tissue was consistent with reduced inflammation in the human microbiota colonized mice, with significantly reduced levels of IFN-γ, MCP-1 (p < 0.001), IL-6, IL-10 and IL-5 (ANOVA, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3D). These findings may either reflect a fundamental difference between colonization with microbiota from the same host species compared to a different species, or may be due to different components of the gut microbiota exerting variable effects on airway inflammation. We have previously shown that mice inoculated with human feces with or without the 4 bacterial genera associated with asthma development in infants differed in lung inflammation based on production of IFNγ, TNF and IL-6, supporting the latter hypothesis.6 These findings confirm that, although lung inflammation is reduced in human microbiota colonized mice compared with mouse microbiota colonized mice, there remains measurable inflammation of mixed cellularity which is sufficient to identify changes after modification of the microbiota, enabling assessment of possible therapeutic interventions in this model. In addition, although asthma has historically been studied as an allergic Th2-type disease, recent transcriptomic studies of bronchial epithelial cells in humans indicated that a high Th2 phenotype is present in only 50% of asthmatics,14,15 suggesting that an animal model exhibiting a mixed immune cell infiltrate will be useful to study an immune signature present in a large proportion of asthmatics that do not fit the classic asthma paradigm.

The gut microbiota and development of asthma in school-aged children

Identification of bacterial genera associated with the development of asthma6 was based on stool samples from participants at 3 months and 1 y of age from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study, which includes children from birth to 5 y of age. The Asthma Predictive Index (API)16 at 3 y of age was used to predict the presence of active asthma at school age, and while a positive API at 3 y is associated with a 77% chance of active asthma at school age, the children in the atopy + wheeze phenotype (used as the asthma ‘extreme phenotype') were not followed to school age to confirm this, as this was beyond the scope of the original study (and the children had not reached school age). Therefore some of these children may not go on to develop asthma at school age, and other children who did not have symptoms of atopy and/or wheeze in the early years of childhood may develop asthma later on.

In order to investigate differences in the gut microbiota of children with confirmed asthma compared with healthy controls, we recruited school aged children (between 6 and 17 y old; Table 1) with asthma and atopy (reflecting the asthma ‘extreme phenotype' used in the younger infants) and compared their microbiota composition and effects on airway inflammation in the murine OVA model.

Table 1.

Demographic features of children with asthma (cases) and healthy control subjects.

| ID number | Asthma/control | Age (years) | Sex | Asthma treatment at time of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Asthma | 10 | M | Inhaled fluticasone 50 mcg once dailyˆ |

| A2 | Asthma | 7 | F | Inhaled fluticasone 500 mcg/salmeterol 100 mcg twice dailyˆ |

| A3 | Asthma | 8 | M | Inhaled ciclesonide 200 mcg once dailyˆ |

| A4 | Asthma | 8 | F | Inhaled budesonide 100 mcg/formoterol 6 mcg twice dailyˆ |

| A5 | Asthma | 15 | M | Inhaled beclomethasone 100 mcg twice dailyˆ |

| C1 | Control | 9 | M | * |

| C2 | Control | 6 | F | * |

| C3 | Control | 6 | F | * |

| C4 | Control | 9 | M | * |

| C5 | Control | 6 | M | * |

| C6 | Control | 10 | M | * |

| C7 | Control | 9 | F | * |

Note.

All children with asthma also receiving inhaled salbutamol to be taken as required

Healthy control subjects not on any asthma treatment

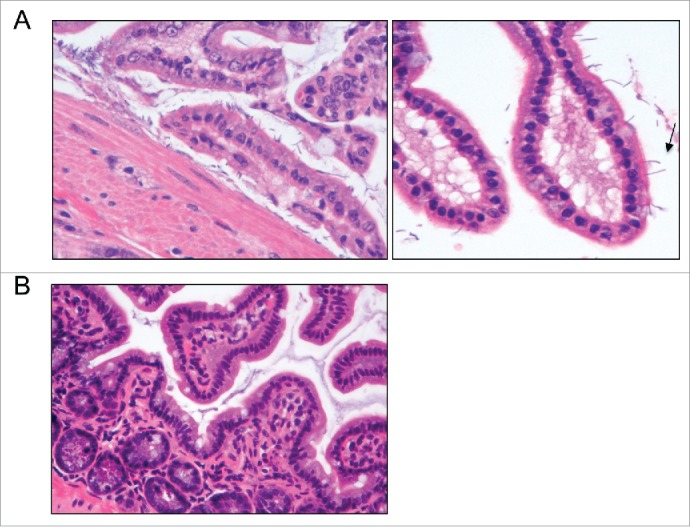

There was no significant difference in overall composition of the gut microbiota between a convenience sample of school-aged children with asthma and atopy (n = 5) and a group of age-matched healthy controls (n = 7) at the level of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (Fig. 4A). Overall, the microbiota was more diverse than found in infants. Principal component analysis and calculation of the Shannon diversity index confirmed that there were no significant differences between the 2 groups (Fig. 4B–C). Further, there were no differential OTUs between asthmatics and healthy controls after statistical analysis (Mann-Whitney and Bonferroni or FDR). In the OVA model of airway inflammation there was no difference in the number of inflammatory cells between mice inoculated with feces from children with asthma compared to healthy controls, both in terms of overall cellular infiltrate and also when different cell types were examined individually (Fig. 4D–E). These studies add to the findings of our original study,6 further suggesting that the critical window where the gut microbiota appear to influence the development of asthma and atopic diseases appears to be in the first 3 months of life, although the sample size in this study was small and a larger study may be needed to assess if there is an impact of the gut microbiota in later life.

Figure 4.

Microbiota from asthmatics did not differ from healthy controls or influence murine asthma phenotype. (A) Family-level relative abundance of microbial taxa from feces of 7 healthy controls and 5 asthmatics, aged 6–17 y. Multivariate analysis by principal component analysis (PCA; B) and α-diversity (Shannon diversity index, C) among asthmatics and healthy controls. (D) Total cellular infiltrates from BALs of mice colonized with 3 cases (asthma) or 2 controls (control) and later challenged with OVA (Nasthma = 23, Ncontrol = 16). (E) Differential leukocyte counts from BALs in D.

Existing challenges and new insights

We have made significant progress in our understanding of the influence of the early infant gut microbiota on development of asthma in children, providing the opportunity for the development of early diagnostic tests and potential intervention to reduce the risk of asthma via probiotic-like approaches. Our findings suggest that focus should be on the first 3 months of life as differences in the microbiota between children at risk of asthma were not found in later infancy or childhood. Humanized gut microbiota mouse models provide a valid experimental system to test any such interventions, and similar models are likely to be highly valuable in increasing our understanding of the gut microbiota on other diseases, including those which may not be directly linked to immune development.

Methods

Mice

GF Swiss Webster mice were ordered from Taconic and kept in a specific pathogen-free facility at University of British Columbia. All experiments were in accordance with the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee guidelines.

Bacterial inoculum preparation and inoculation

Frozen and fresh feces from one child or frozen feces from conventionally raised Swiss Webster mice were used to orally inoculate GF mice as previously described.6 A fecal slurry was prepared by scraping a piece of fecal material with a sterile scalpel and combining it with 1 ml of PBS reduced with 0.05% of cysteine-HCl to protect anaerobic species. Immediately upon arrival, GF mice were randomly selected to be orally gavaged with 30μl of the fecal slurry. Oral gavages with the different microbial treatments were repeated on days 2, 4 and 6-post arrival.

Experimental lung inflammation model

Experimental murine lung inflammation was induced in mice previously colonized with murine or human feces, as previously described17 with minor modifications. Although this model does not fully recapitulate the phenotype of human allergic asthma, it is a useful model for evaluating many aspects of this lung inflammatory disease. Mice were sensitized intraperitoneally with 10 mg of grade V OVA and 1.3 mg of aluminum hydroxide (both from Sigma) on days 0 and 7 (3 weeks after initial microbial colonization). On days 21, 22, 23, and 25, mice were challenged intranasally with 50 mg of grade V OVA (Sigma). On day 26, mice were anaesthetized with ketamine (200 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), and blood was collected by cardiac puncture. After sacrifice, BALs were performed by 3 × 1 ml washes with PBS. Total BAL counts were blindly assessed by counting cells in a hemocytometer. Eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes were quantified from Cytospins (Thermo Shandon) stained with Hema Stain (Fisher Scientific), based on standard morphological criteria. Lung lobes were collected and homogenized in PBS plus protease inhibitors (Roche, Branford, Conn). Supernatants were analyzed for cytokines. All protocols used in these experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of British Columbia.

Splenocyte and intestinal tissue culture

Intestinal tissue culture was performed as previously described.18 Whole colons and approximately 8 cm of proximal ileum were removed, flushed with PBS, and 1/4 of the tissue was cut longitudinally and resuspended in tissue culture plates in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 U/ml), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Branford, Conn). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h. Supernatants of colons and ilea were removed and stored at −20°C for cytokine and IgA analysis.

Spleens were dissected, minced between 2 frosted glass slides and strained through a 40 µm mesh strainer. Cells were harvested in complete RPMI-1640 with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS) and depleted of red blood cells by osmotic shock with distilled water. Cell numbers were calculated with the Z2 particle count and size analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Splenic cells were placed into the wells of 96 well plates at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells per well. Cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3e clone 145-2C11 as a stimulation control (PharMingen, Canada) or medium alone as a negative control for 72 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2. After 48 h of incubation, the plates were centrifuged and 150 µl supernatants were removed and stored for cytokine assays.

Cytokines and IgA determination

Supernatants from lung homogenates, splenocyte and intestinal tissue cultures were used to determine IL-17, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-1β, IL-12p70, IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, MCP-1, IL-2, and IL-10 by cytokine bead array flex sets (BD Biosciences). Analysis was performed using an LSR II (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed with FlowJo 8.7 software (TreeStar, Ashland, Ore). TGF-β and immunoglobulin (Ig) A (only in gut samples) concentrations were assayed by ELISA using DuoSet kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Cytokine and IgA concentrations were normalized to total protein, assessed by Bradford assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill).

Histology

Distal ileum and whole colons were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. Samples were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for light microscopy examination. The slides were reviewed in a blinded fashion by a pathologist (MN).

16S Microbial community analysis

DNA was extracted from 1–2 pellets of mouse stool. Samples were mechanically lysed using MO BIO dry bead tubes (MO BIO Laboratories) and the FastPrep homogenizer (FastPrep Instrument, MP Biochemicals) before DNA extraction with the Qiagen DNA Stool Mini Kit.

All samples were amplified by PCR in triplicate using barcoded primer pairs flanking the V3 region of the 16S gene as previously described.19 Each 50 ml of PCR contained 22 ml of water, 25 ml of TopTaq Master Mix, 0.5 ml of each forward and reverse barcoded primer, and 2 ml of template DNA. The PCR program consisted of an initial DNA denaturation step at 95°C (5 min), 25 cycles of DNA denaturation at 95°C (1min), an annealing step at 50°C (1min), an elongation step at 72°C (1 min), and a final elongation step at 72°C (7 min). Controls without template DNA were included to ensure that no contamination occurred. Amplicons were run on a 2% agarose gel to ensure adequate amplification. Amplicons displaying bands at approximately 160 bp were purified using the illustra GFX PCR DNA Purification kit. Purified samples were diluted 1:50 and quantified using PicoGreen (Invitrogen) in the TECAN M200 (excitation at 480 nm and emission at 520 nm).

Pooled PCR amplicons were diluted to 20 ng/ml and sequenced at the V3 hypervariable region using Hi-Seq 2000 bidirectional Illumina sequencing and Cluster Kit v4 (Macrogen Inc.). Library preparation was done using TruSeq DNA Sample Prep v2 Kit (Illumina) with 100 ng of DNA sample and QC library by Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 Chip (Agilent).

Sequences were preprocessed, denoised, and quality filtered by size using Mothur.20 Representative sequences were clustered into OTUs using CrunchClust21 and classified against the Greengenes Database22 according to 97% similarity. Any OTUs present less than 5 times among all samples were removed from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Fecal microbial diversity and the relative abundance of bacterial taxa were assessed using Phyloseq23 along with additional R-based computational tools in R-studio (R-Studio, Boston, MA). Principal components analysis (PCA) was conducted using MetaboAnalyst24 and statistically confirmed by Permanova. The Shannon diversity index was calculated using Phyloseq and statistically confirmed by Mann-Whitney (GraphPad Prism software, version 5c, San Diego, CA). Differences between groups in mice experiments were determined by Student t-test (2 groups) or ANOVA (>2 groups). Statistical significance was defined as P ≤ 0 .05.

Human study subjects

Children with confirmed asthma and atopy were recruited from the allergy clinic at BC Children's Hospital, Vancouver, Canada. Children had to fulfil all inclusion criteria: (i) aged between 6 y and 17 years; (ii) diagnosis of asthma during the last 3 years, confirmed by a pediatric allergist/immunologist with expertise in asthma; (iii) confirmation of atopic status on the basis of a positive skin prick test to any aeroallergen at any time; (iv) receiving anti-inflammatory therapy for asthma (for example, inhaled corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists); (v) being followed in the hospital outpatient clinic by a pediatric allergist/immunologist with expertise in asthma. Healthy control children were recruited via the orthopedic clinic and had to be between 6 y and 17 y of age with no diagnosis of asthma at any time and no known allergic or atopic disease. Exclusion criteria were: (i) treatment with systemic anti-microbial drugs or administration of probiotics for medical reasons within 1 month of obtaining stool sample; (ii) known acute or chronic gastro-intestinal disorder which may alter the natural microbiome (including but not restricted to gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease).

Human fecal samples

Fecal samples were collected by parents and/or children and kept in the home refrigerator prior to collection by a member of the study team. Samples were frozen within 24 hours of being excreted.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia Children & Women's Health Research Ethics Board (Refs: H12-02612; CW12-0277).

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

MCA, SLR, SET and BBF filed a provisional patent 62/132,042, entitled “Intestinal bacterial composition and methods to detect and prevent asthma,” in the United States on 3 December 2014. MS is an investigator on investigator-initiated research grants from Pfizer unrelated to this study. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the children and families who contributed time and samples for these studies. SET holds the Aubrey J. Tingle Professorship in Pediatric Immunology and is a clinical scholar of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. BBF is the UBC Peter Wall Distinguished Professor.

Funding

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; grants CHM-94316 and CMF 108029). EMB is supported by a Doctoral Research Award from CIHR and a 4YF scholarship from the University of British Columbia.

References

- [1].Asher I, Pearce N. Global burden of asthma among children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18:1269-78; PMID:25299857; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5588/ijtld.14.0170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Amenyogbe N, Brown EM, Finlay B. The intestinal microbiome in early life: health and disease. Front Immunol 2014; 5:427; PMID:25250028; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Arnold IC, Dehzad N, Reuter S, Martin H, Becher B, Taube C, Müller A. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:3088-93; PMID:21737881; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI45041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Russell SL, Gold MJ, Willing BP, Thorson L, McNagny KM, Finlay BB. Perinatal antibiotic treatment affects murine microbiota, immune responses and allergic asthma. Gut Microbes 2013; 4:158-64; PMID:23333861; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/gmic.23567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cahenzli J, Koller Y, Wyss M, Geuking MB, McCoy KD. Intestinal microbial diversity during early-life colonization shapes long-term IgE levels. Cell Host Microbe 2013; 14:559-70; PMID:24237701; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Dimitriu PA, Thorson L, Russell S, Yurist-Doutsch S, Kuzeljevic B, Gold MJ, Britton HM, Lefebvre DL, et al.. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:307ra152; PMID:26424567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chung H, Pamp SJ, Hill JA, Surana NK, Edelman SM, Troy EB, Reading NC, Villablanca EJ, Wang S, Mora JR, et al.. Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell 2012; 149:1578-93; PMID:22726443; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:11070-5; PMID:16033867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0504978102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med 2009; 1:6ra14; PMID:20368178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marcobal A, Kashyap PC, Nelson TA, Aronov PA, Donia MS, Spormann A, Fischbach MA, Sonnenburg JL. A metabolomic view of how the human gut microbiota impacts the host metabolome using humanized and gnotobiotic mice. ISME J 2013; 7:1933-43; PMID:23739052; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ismej.2013.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Seedorf H, Griffin NW, Ridaura VK, Reyes A, Cheng J, Rey FE, Smith MI, Simon GM, Scheffrahn RH, Woebken D, et al.. Bacteria from diverse habitats colonize and compete in the mouse gut. Cell 2014; 159:253-66; PMID:25284151; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McCutcheon JP, Moran NA. Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012; 10:13-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Brestoff JR, Artis D. Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:676-84; PMID:23778795; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bhakta NR, Woodruff PG. Human asthma phenotypes: from the clinic, to cytokines, and back again. Immunol Rev 2011; 242:220-32; PMID:21682748; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01032.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180:388-95; PMID:19483109; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, Martinez FD. A clinical index to define risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162:1403-6; PMID:11029352; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Blanchet MR, Maltby S, Haddon DJ, Merkens H, Zbytnuik L, McNagny KM. CD34 facilitates the development of allergic asthma. Blood 2007; 110:2005-12; PMID:17557898; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Madsen K, Cornish A, Soper P, McKaigney C, Jijon H, Yachimec C, Doyle J, Jewell L, De Simone C. Probiotic bacteria enhance murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology 2001; 121:580-91; PMID:11522742; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/gast.2001.27224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bartram AK, Lynch MD, Stearns JC, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Neufeld JD. Generation of multimillion-sequence 16S rRNA gene libraries from complex microbial communities by assembling paired-end illumina reads. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011; 77:3846-52; PMID:21460107; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.02772-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, et al.. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009; 75:7537-41; PMID:19801464; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.01541-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hartmann M, Howes CG, VanInsberghe D, Yu H, Bachar D, Christen R, Henrik Nilsson R, Hallam SJ, Mohn WW. Significant and persistent impact of timber harvesting on soil microbial communities in Northern coniferous forests. ISME J 2012; 6:2199-218; PMID:22855212; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ismej.2012.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:5069-72; PMID:16820507; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 2013; 8:e61217; PMID:23630581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xia J, Mandal R, Sinelnikov IV, Broadhurst D, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 2.0–a comprehensive server for metabolomic data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:W127-33; PMID:22553367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gks374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Original Article Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Dimitriu PA, Thorson L, Russell S, Yurist-Doutsch S, Kuzeljevic B, Gold MJ, Britton HM, Lefebvre DL, et al.. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Transl Med 2015. September 30; 7(307):307ra152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]