Abstract

Treatment of tuberculosis (TB) has been a therapeutic challenge because of not only the naturally high resistance level of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to antibiotics but also the newly acquired mutations that confer further resistance. Currently standardized regimens require patients to daily ingest up to four drugs under direct observation of a healthcare worker for a period of 6–9 months. Although they are quite effective in treating drug susceptible TB, these lengthy treatments often lead to patient non-adherence, which catalyzes for the emergence of M. tuberculosis strains that are increasingly resistant to the few available anti-TB drugs. The rapid evolution of M. tuberculosis, from mono-drug-resistant to multiple drug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and most recently totally drug-resistant strains, is threatening to make TB once again an untreatable disease if new therapeutic options do not soon become available. Here, I discuss the molecular mechanisms by which M. tuberculosis confers its profound resistance to antibiotics. This knowledge may help in developing novel strategies for weakening drug resistance, thus enhancing the potency of available antibiotics against both drug susceptible and resistant M. tuberculosis strains.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Drug resistance, Antibiotic, Mycobacterium, Mechanism, Bactericidal

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), once known as “consumption” or phthisis, was one of the deadliest diseases to humanity for millennia (Birnbaum et al. 1891). Until the late eighteenth century, it was almost a death sentence to patients diagnosed with this disease. The discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the causative agent by Dr. Robert Koch in 1882, followed by the sanatorium movement in Europe and the USA, began to bring better treatments to TB. However, it only became curable with the later discovery of antibiotics, which have brought on a real revolution in TB chemotherapy. Starting with streptomycin and p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) in 1945, many drugs were developed for TB treatment during this so-called golden age of antibiotics (1940s–1960s). The introduction of these drugs, with isoniazid, ethambutol, rifampicin and pyrazinamide being of most significance, to TB treatment immediately led to a sharp and continuous decline of TB incidence throughout the world. In the 1960s, it was generally thought that TB was no longer a public health concern and that it would soon be eradicated (Myers 1963). However, the disease suddenly came back in the 1980s in association with the rising epidemic of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the emergence of drug-resistant forms.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is now considered one of the most successful pathogens among those causing infectious diseases, as it was once before. The bacillus currently infects one-third of the world population, equivalent to around two billion people (Corbett et al. 2003). Besides its innate ability to survive host defense mechanisms, M. tuberculosis is able to resist most antimicrobial agents currently available (Nguyen and Pieters 2009). As a result, the existing chemotherapeutic options for TB treatment are severely limited (Table 1). Prolonged regimens using the same few drugs have resulted in poor patient compliance and, as a result, the emergence of strains that are increasingly resistant to the available anti-TB drugs. The careless use of antibiotics has created a selective pressure pushing a rapid evolution of M. tuberculosis, marching from mono-drug resistant to multidrug resistant (MDR), extensively drug resistant (XDR), and eventually totally drug resistant (TDR), through sequential accumulation of resistance mutations (Table 2) (Dorman and Chaisson 2007; Ormerod 2005; Udwadia 2012). Infections with XDR or TDR M. tuberculosis strains are essentially incurable by the current anti-TB drugs, threatening to destabilize global TB control. Novel therapeutics are urgently needed to tackle the current epidemic of drug-resistant TB. In addition to the development of new classes of anti-TB drugs, non-traditional approaches such as targeting resistance or repurposing old drugs are under scrutiny (Nguyen 2012). The success of these approaches would require better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that underlies drug resistance in M. tuberculosis (Nguyen and Jacobs 2012).

Table 1.

Anti-TB drugs

| Drug | Year of discovery |

|---|---|

| First-line drugs | |

| Isoniazid | 1952 |

| Rifampicin | 1966 |

| Rifabutina | 1980 |

| Rifapentinea | 1965 |

| Pyrazinamide | 1952 |

| Ethambutol | 1961 |

| Second-line drugs | |

| Cycloserine | 1952 |

| Ethionamide | 1956 |

| p-Aminosalicylic acid (PAS) | 1946 |

| Streptomycin | 1944 |

| Amikacin | 1972 |

| Kanamycina | 1957 |

| Capreomycin | 1963 |

| Levofloxacina (Levaquin, DR3355, Daiichi) | 1986 |

| Moxifloxacina (Avelox, BAY 12-8039) | 1996 |

| Gatifloxacina (Tequin, AM-1155) | 1992 |

| New drugs being developed or trialed for TB | |

| Sirturo (bedaquiline or TMC207) | Phase 3 |

| Delamanid (OPC-67683) | Phase 3 |

| AZD5847 | Phase 2 |

| PA-824 | Phase 2 |

| Linezolid | Phase 2 |

| SQ-109 | Phase 2 |

| PNU-100480 | Phase 1 |

These drugs are suggested for use in selected cases, and not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for TB treatment. Some of them are undergoing trials for FDA approval

Table 2.

Genes involved in acquired drug resistance in M. tuberculosis

| Gene | Encoded protein | Protein function | Affected drug | Drug’s mode of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| katG | Catalase–peroxidase | Prodrug activation | Isoniazid | Inhibiting mycolic acid biosynthesis and other metabolic processes |

| inhA | Enoyl ACP reductase | Drug target | ||

| ndh | NADH dehydrogenase II | Modulation of NADH/NAD ratio | ||

| ahpC | Alkyl hydroperoxidase | Oxidative stress resistance | ||

| rpoB | β-Subunit of RNA polymerase | Drug target | Rifampicin | Inhibiting transcription |

| pncA | Pyrazinamidase | Prodrug activation | Pyrazinamide | Inhibiting trans-translation |

| rspA | S1 ribosomal protein | Drug target | ||

| embCAB | Arabinosyltransferases | Drug target | Ethambutol | Inhibiting arabinogalactan synthesis |

| embR | embCAB transcription regulator | Regulation of embCAB expression | ||

| rpsL | S12 ribosomal protein | Drug target | Streptomycin | Inhibiting protein synthesis |

| rrs | 16S rRNA | Drug target | ||

| gidB | 16S rRNA methyltransferase | Modification of drug target | ||

| whiB7 | MDR transcription regulator | Regulation of drug resistance genes | ||

| rrs | 16S ribosomal RNA | Drug target | Amikacin/kanamycin | Inhibiting protein synthesis |

| eis | Aminoglycoside acetyltransferase | Drug inactivation | ||

| whiB7 | MDR transcription regulator | Regulation of eis expression | ||

| ethA | Flavin monooxygenase | Prodrug activation | Ethionamide | Inhibiting mycolate biosynthesis |

| ethR | ethA transcription repressor | Regulation of ethA expression | ||

| inhA | Enoyl ACP reductase | Drug target | ||

| ndh | NADH dehydrogenase II | Modulation of NADH/NAD ratio | ||

| mshA | Glycosyltransferase | Prodrug activation | ||

| gyrA | DNA gyrase subunit A | Drug target | Fluoroquinolones | Inhibiting DNA gyrase |

| gyrB | DNA gyrase subunit B | Drug binding | ||

| alrA | D-Alanine racemase | Drug target | D-Cycloserine | Inhibiting peptidoglycan synthesis |

| cycA | D-Alanine-D-alanine ligase | Drug target | ||

| ddl | Amino acid transporter | Drug uptake | ||

| thyA | Thymidylate synthase A | dTTP synthesis | p-Aminosalicylic acid (PAS) | Inhibiting folate biosynthesis |

| dfrA | Dihydrofolate reductase | Drug target | ||

| folC | Dihydrofolate synthase | Prodrug activation | ||

| ribD | Dihydrofolate reductase analog | Replacement of drug target activity | ||

| tlyA | rRNA methyltransferase | Ribosome protection | Capreomycin | Inhibiting protein synthesis |

| rrs | 16S ribosomal RNA | Drug target |

Acquired resistance

Acquired antibiotic resistance may occur in bacteria through either mutations or horizontal gene transfer mediated by phages, plasmids or transposon elements. In M. tuberculosis, horizontal transfer of drug resistance genes has not been reported; but resistance mostly arises from chromosomal mutations under the selective pressure of antibiotic use. M. tuberculosis genes to which mutations confer drug resistance are listed in Table 2.

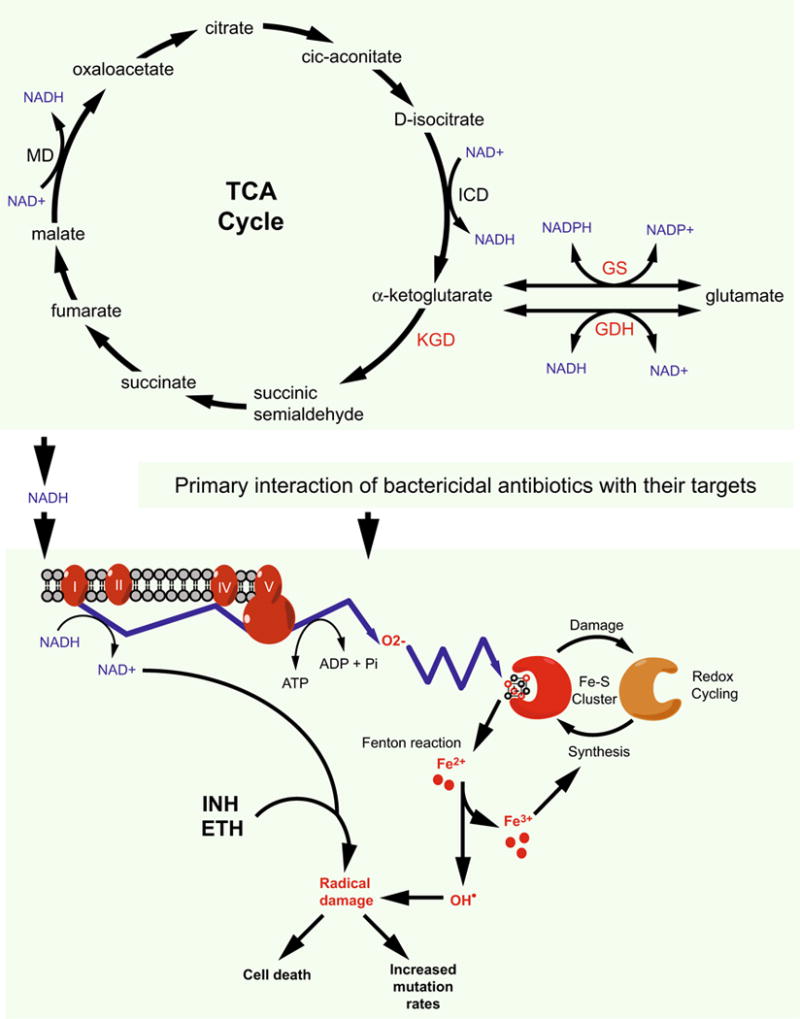

The progression of drug resistance in M. tuberculosis epitomized the Darwin’s theory of evolution. Antibiotic resistance becomes predominant traits in M. tuberculosis populations because they bring survival advantages to the arising mutants under selective pressure. The continuous drug exposure during lengthy regimens, together with patients’ non-adherence, has pushed evolution to select for resistant mutants that otherwise would never predominate the population because of their reduced fitness. This process, occurring during combination therapies, has created a steady evolution of M. tuberculosis strains, gradually becoming resistant to all existing drugs. In addition to the survival and selection, sublethal exposures to bactericidal antibiotics might have mediated radical-induced mutagenesis (Kohanski et al. 2010a), thus promoting the emergence of multidrug resistance phenotypes in pathogenic bacteria including M. tuberculosis. TB drugs such as isoniazid and ethionamide are prodrugs, which require activation by redox enzymes in the mycobacterial cytoplasm to become cytotoxic. The prodrug activation process produces reactive oxygen and radicals that exert the mycobactericidal activity (Fig. 1) (Ito et al. 1992; Wang et al. 1998). However, if these reactive oxygen and radicals fail to kill the mycobacterial cell, they will turn bad by promoting cellular mutagenesis and the emergence of drug resistance mutations.

Fig. 1.

Possible correlation among TCA cycle, cellular redox balance and the bactericidal activity of antibiotics in M. tuberculosis. Interactions of bactericidal antibiotics with their targets trigger the oxidation of NADH, which is produced by the TCA cycle, through the electron transport chain. This results in an increased production of superoxide that destroys iron–sulfur clusters, thus releasing iron for the oxidation of the Fenton reaction. The Fenton reaction produces hydroxyl radicals that damage nucleic acids, proteins and lipid, leading to cell death. However, if these hydroxyl radicals fail to kill a bacterial cell, they may promote mutagenesis converting the cell to a drug-resistant mutant. Similarly, the anti-TB drugs isoniazid (INH) and ethionamide (ETH) kill mycobacteria by converting to free radicals, which may thus contribute to the formation of MDR M. tuberculosis strains. MD malate dehydrogenase, ICD isocitrate dehydrogenase. Redrawn with modifications from (Kohanski et al. 2007) with permission

The following sections will highlight recent progress in understanding the acquired antibiotic resistance mechanisms in M. tuberculosis.

p-Aminosalicylic acid: mode of action and resistance

p-Aminosalicylic acid (PAS) is currently classified as one of the second-line anti-TB drugs (Table 1), which are added to regimens for treating cases of multidrug resistant TB. This antibiotic is highly specific for acid-fast bacteria such as those of the Nocardia and Mycobacterium genera (Trnka and Mison 1988). PAS is mostly bacteriostatic although it was reported to confer bactericidality in certain conditions (Jindani et al. 1980; Wissensehaftliche-ArbeRsgemeinsehaft-fur-die-Therapie-yon-Lungenkrankheiten 1969; Xie et al. 2005).

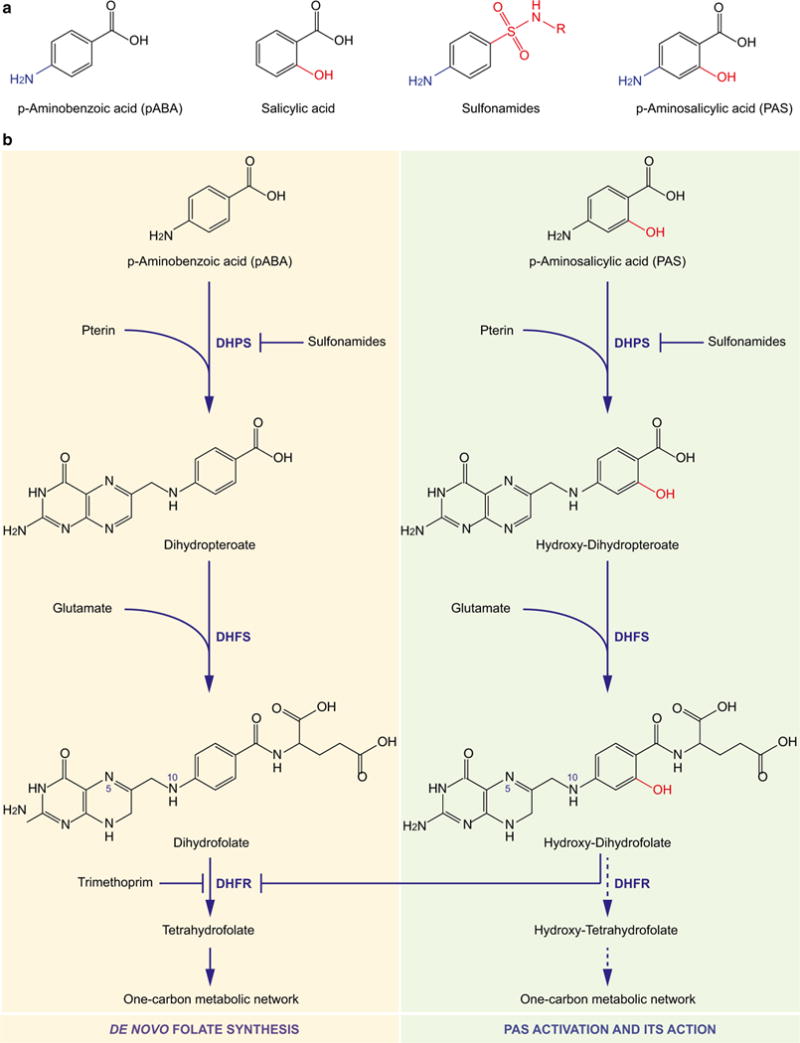

PAS was first synthesized in 1902 by Seidel and Bittner and then rediscovered as having anti-TB activity in 1946 by Lehman (Lehmann 1946; Seidel and Bittner 1902). During the early 1940s, researchers working on antibiotic development were influenced by the “competitive enzyme inhibition” theory of Woods and Fildes, who explained that sulfonamides, structural analogs of the growth factor p-aminobenzoic acid (pABA), inhibit bacterial growth by outcompeting pABA and hence inhibit the enzyme dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) in the de novo folate synthesis (Fig. 2) (Darzins 1958; Henry 1943). In the same way, the discovery of PAS started with the observation by Bernheim in 1940 that salicylic (or 2-hydroxy benzoic acid) acid induced oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production in M. tuberculosis (Bernheim 1940), suggesting that salicylic acid might function as an important intermediate of an unknown metabolic pathway. This observation, together with the Woods and Fildes theory, led to the hypothesis that structural analogs of salicylic acid might inhibit growth of the tubercle bacillus by outcompeting salicylic acid in the as-yet-unknown metabolic pathway. Based on this hypothesis, Lehmann screened more than fifty derivatives of salicylic acid, leading him to identify PAS as an effective anti-TB agent (Darzins 1958; Lehmann 1946).

Fig. 2.

Activation of p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) and its inhibition of the folate pathway. a Analogous structures of p-aminobenzoic acid (pABA), salicylic acid, sulfonamides and p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) illustrated from left to right, respectively. Chemical groups highlighted in blue and red indicate variations among the chemicals. b Conversion of pABA (left, yellow) and PAS (right, green) using the same enzymes of the de novo folate synthesis, in which DHPS and DHFR are targets of sulfonamides and trimethoprim, respectively. The activated form of PAS, hydroxy-dihydrofolate that is produced following the two chemical conversions catalyzed by DHPS and DHFS adding the pteridine and glutamate groups, respectively, is proposed to inhibit the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate catalyzed by DHFR activity. Alternatively, hydroxy-dihydrofolate can be further converted to hydroxy-tetrahydrofolate by DHFR and even further to other folate species carrying one-carbon groups at position N5 and/or N10, by enzymes of the one-carbon metabolic network. One or more of these hydroxyfolate forms may then interfere with this very pathway causing growth arrest or even death, for example, through inducing thymineless death. DHPS dihydropteroate synthase, DHFS dihydrofolate synthase, DHFR dihydrofolate reductase (color figure online)

Because the structure of PAS mimics not only salicylic acid but also pABA (Fig. 2a), which is required for folate synthesis, it has been debated as whether PAS inhibits the synthesis of salicylic acid and/or its conversion to the siderophore mycobactin (see “Salicylic acid and mycobactin” section), or the de novo folate synthesis (see “Folate pathway” section).

Salicylic acid and mycobactin

Early work by Ivánovics showed that the bacteriostatic activity of PAS could be antagonized by high concentrations of salicylic acid (Ivanovics 1949), suggesting that PAS might target a mycobacterial metabolic pathway related to salicylic acid. It was later proposed by the Ratledge group that salicylic acid is the precursor for the synthesis of mycobactin, the iron chelator required for mycobacterial iron acquisition and M. tuberculosis survival in host macrophages (Adilakshmi et al. 2000; De Voss et al. 2000; Ratledge 2004). Treatment with PAS caused accumulation of salicylic acid and reduced cellular level of mycobactin, indicating that these connected pathways might be the cellular target of PAS in mycobacteria (Adilakshmi et al. 2000; Nagachar and Ratledge 2010; Ratledge 2004). More importantly, M. smegmatis mutants defective in salicylic acid synthesis were more sensitive to PAS (Nagachar and Ratledge 2010) than the wild type, further supporting the hypothesis that a salicylic acid-related metabolism is targeted by PAS. Unfortunately, no further studies have been done in M. tuberculosis. Also, the precise target of PAS in the salicylic acid synthesis or its conversion to mycobactin, as well as the PAS resistance mechanisms related to this pathway, has since remained uncharacterized.

Folate pathway

Similar to sulfonamides, PAS was first shown to be antagonized by exogenous pABA (Hedgecock 1958; Youmans et al. 1947), suggesting that PAS might target dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS), the enzyme that catalyzes the condensation of pABA to pteridine to form dihydropteroate, in the de novo folate synthesis (Fig. 2b). A later study supported this hypothesis by showing that disruption of thyA encoding thymidylate synthase, an enzyme of the folate-dependent one-carbon metabolic network, by transposon insertions resulted in an increased PAS resistance (Rengarajan et al. 2004). Surprisingly, sulfonamides are antagonistic to PAS, but not synergistic as expected for two inhibitors targeting the same enzyme or pathway. In addition, sulfonamide resistance, which is mostly associated with DHPS, does not confer cross-resistance to PAS (Yegian and Long 1951). Also, in vitro enzymatic assays showed that PAS, unlike sulfonamides, had negligible inhibitory activity against purified M. tuberculosis DHPS (Nopponpunth et al. 1999). Together, these observations indicated that PAS inhibits target(s) in the folate pathway, but that target is not DHPS.

Two recent metabolomic studies further investigating the effect of PAS on M. tuberculosis’ folate metabolism revealed that PAS is a prodrug that is first converted to hydroxy-dihydropteroate and then hydroxy-dihydrofolate, by DHPS and dihydrofolate synthase (DHFS), respectively (Fig. 2b) (Chakraborty et al. 2013; Zheng et al. 2013). It was proposed that hydroxy-dihydrofolate then inhibits dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), the same enzyme inhibited by trimethoprim and other DHFR inhibitors (Fig. 2b) (Zheng et al. 2013). To support this hypothesis, Zheng et al. (2013) showed that overexpression of DHFR, encoded by dfrA, or a riboflavin biosynthesis protein with secondary DHFR activity, encoded by ribD, resulted in PAS resistance in M. tuberculosis. While PAS itself shows no inhibition against purified M. tuberculosis dfrA-encoded DHFR, cell lysates from PAS-treated M. tuberculosis contained small molecule(s) that inhibit DHFR activity (Zheng et al. 2013). The cellular production of this DHFR-inhibitory small molecule(s) was inhibited when cells were treated with sulfonamides, which inhibit DHPS (Zheng et al. 2013). This knowledge has now explained why sulfonamides are antagonistic, but not synergistic against PAS.

Besides hydroxy-dihydrofolate targeting DHFR, other PAS-derived metabolites may be formed to target other enzymes of the one-carbon metabolic network. For example, hydroxy-dihydrofolate may be reduced to hydroxy-tetrahydrofolate by DfrA, or RibD, or other as-yet-unidentified DHFRs. Hydroxy-tetrahydrofolate is then further converted to hydroxyl-tetrahydrofolate derivatives carrying one-carbon groups at position N5 and/or N10, by enzymes of the one-carbon metabolic network. One or more of these hydroxy-tetrahydrofolate species may then interfere with this very pathway causing growth arrest or cell death. In fact, metabolomic studies of PAS-treated M. tuberculosis cells revealed cellular accumulation of 5-amino-1-(5-phospho-D-ribosyl) imidazole-4-carboxamide (AICAR), serine, homocysteine and deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) (Chakraborty et al. 2013). While the accumulation of homocysteine may indicate an impaired methionine synthase that converts 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate back to tetrahydrofolate, the increased cellular level of dUMP may represent an indicator of thymineless death caused by defects in thymidylate synthase activity. This impaired homeostasis, namely the unusual accumulation of metabolites, in the one-carbon metabolism was repaired by exogenous pABA (Chakraborty et al. 2013). Together, these observations indicated that PAS-derived metabolites may interfere with many enzymes of the folate pathway, in addition to DHFR.

Although these two studies (Chakraborty et al. 2013; Zheng et al. 2013) set light to the mode of PAS action, many questions remain to be answered, for example, what is the molecular basis that underlies the specificity of PAS to mycobacteria, in particular M. tuberculosis.

Resistance mechanisms

Most acquired PAS resistance mutations in M. tuberculosis have thus far been mapped to thyA, folC, dfrA and ribD (Table 2) (Mathys et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2014; Zheng et al. 2013).

As proposed by Zheng et al. (2013), dfrA and ribD provide cells with DHFR activity that is required for the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate. While DfrA is the target of hydroxyl-dihydrofolate, RibD provides M. tuberculosis with an alternative DHFR activity (Zheng et al. 2013). Therefore, mutations that lead to increased gene expression or enzymatic activities of either DfrA or RibD would rescue cells from the inhibitory activity of PAS.

folC encodes dihydrofolate synthase (DHFS), which converts dihydropteroate to dihydrofolate in the de novo folate synthesis (Fig. 2b, left). Together with DHPS, DHFS helps to activate PAS, converting this prodrug to the activated form, hydroxyl-dihydrofolate (Fig. 2b, right) (Zheng et al. 2013). Thus, mutations affecting this bioconversion, by reducing either folC expression or DHFS enzymatic activity, would result in lower activation of PAS (Zhao et al. 2014), thus reducing the anti-mycobacterial activity of PAS.

As for thyA, it is less clear why mutations in this gene lead to increased PAS resistance. M. tuberculosis possesses two thymidylate synthases, ThyA and ThyX, both of which convert dUMP to dTTP using 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate as the methyl donor. While the ThyX-catalyzed reaction yields tetrahydrofolate as a byproduct, the reaction catalyzed by ThyA makes dihydrofolate that needs to be reduced back to tetrahydrofolate by DHFR before its reentry to the one-carbon metabolic network. ThyA activity would therefore lead to increased cellular requirement for DHFR, the target of PAS, thus possibly making M. tuberculosis more susceptible to the PAS’ mode of action. Alternatively, as dfrA is located immediately downstream of thyA and their intergenic region is only 70 base pairs in length, it is possible that these two genes form an operon sharing a promoter located upstream of thyA. The mutations found in the thyA promoter or its coding region may cause higher dfrA expressions, thereby enhancing PAS resistance as shown by Zheng et al. (2013).

Besides these acquired resistance mechanisms, M. tuberculosis and related pathogenic mycobacteria can actively remove PAS from their cytoplasm through the activity of efflux pumps. For example, the multidrug transporter Tap, which is controlled by the MDR transcription regulator WhiB7 (see below), was recently shown to provide mycobacteria with the intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics including PAS (Ramon-Garcia et al. 2012).

Pyrazinamide: mode of action and resistance

Pyrazinamide is currently classified as one of the first-line anti-TB drugs which is added to shorten treatment regimens. Despite its common use, the precise mode of action of pyrazinamide, its cellular target and how mycobacteria resist this drug have remained poorly understood. Similar to many other anti-TB drugs including isoniazid, ethionamide and PAS, pyrazinamide is a prodrug that needs to be enzymatically activated following its entry into mycobacterial cells. The activation, converting pyrazinamide to its active form, pyrazinoic acid, requires the mycobacterial enzyme pyrazinamidase, which is encoded by the pncA gene (Scorpio and Zhang 1996). Genetic and biochemical experiments established the correlation of cellular production of pyrazinamidase and pyrazinamide resistance in mycobacteria (Bamaga et al. 2002; Boshoff and Mizrahi 2000). Sequencing of pyrazinamide-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates revealed most mutations associated with pncA (Scorpio et al. 1997). However, a small group of low-level pyrazinamide-resistant isolates showed no mutation in pncA, suggesting that some of these strains might carry mutations in genes encoding pyrazinamide target(s).

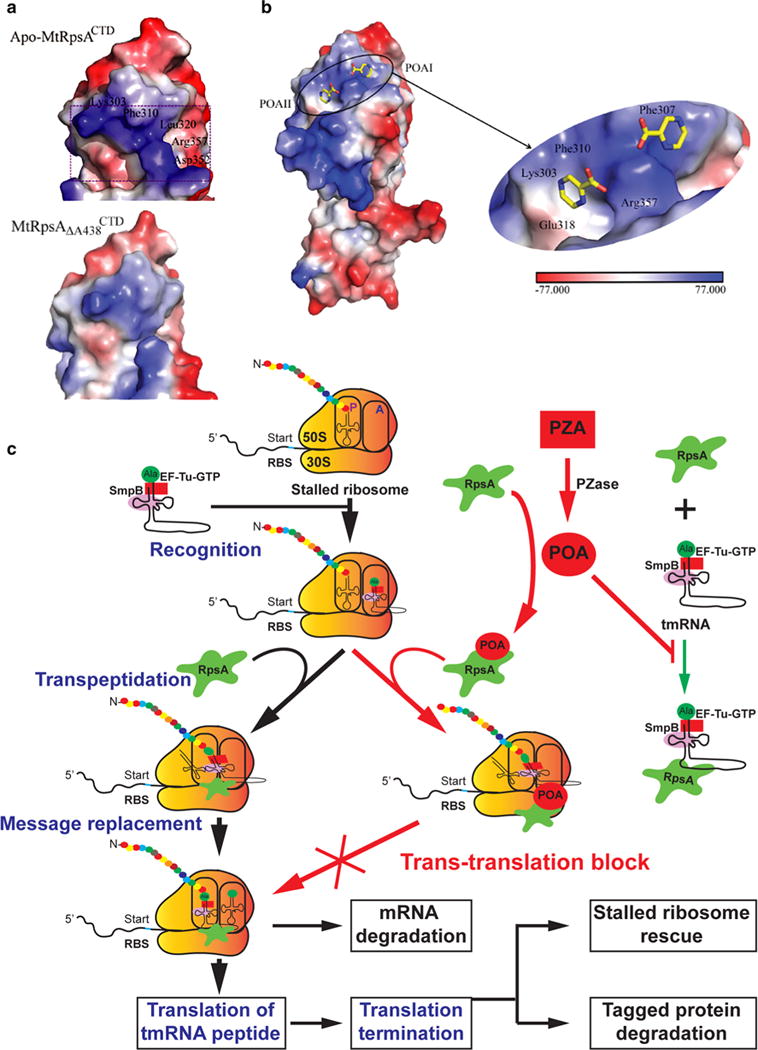

In a screen for M. tuberculosis proteins that bind pyrazinoic acid, the 30S ribosomal protein S1 (RpsA) was identified (Shi et al. 2011). In addition to its ribosomal function in protein synthesis, RpsA also interacts with transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) during trans-translation (Saguy et al. 2007; Wower et al. 2000), a cellular process that (a) rescues ribosomes stalled during translation and (b) degrades the incomplete polypeptide and its messenger RNA (mRNA) (Keiler 2008). In this process, the stalled mRNA is displaced by tmRNA, which encodes a short peptide that is tagged to the stalled protein for subsequent degradation by specific proteases.

Pyrazinoic acid, but not the prodrug pyrazinamide, was shown to inhibit trans-translation by preventing the interaction of RpsA with tmRNA, while overexpression of rpsA enhances pyrazinamide resistance (Shi et al. 2011). Sequencing one of the pncA-unrelated pyrazinamide-resistant strains revealed loss of the codon encoding residue Alanine 438, located near the C-terminus of RpsA, which was later shown to be essential for pyrazinoic acid binding (Shi et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2015). Lack of Alanine 438 does not cause gross structural changes but induces conformational changes in the pyrazinoic acid binding site (Fig. 3a, b) (Yang et al. 2015). An RpsA protein lacking Alanine 438 can still bind tmRNA, but the binding is no longer affected by pyrazinoic acid (Yang et al. 2015). Shi et al. proposed that trans-translation, a process required for bacterial stress survival and recovery from nutrient starvation (Keiler 2008), is the molecular target of pyrazinamide (Fig. 3c). Nevertheless, the significance of rpsA in pyrazinamide resistance among M. tuberculosis clinical isolates remains to be evaluated (Alexander et al. 2012; Tan et al. 2014).

Fig. 3.

Interaction of pyrazinamide (PZA) -derived pyrazinoic acid (POA) with the RpsA protein involved in trans-translation. a Electrostatic surface potentials of the C-terminal domain of M. tuberculosis RpsA (MtRpsACTD, top) and its ΔA438 mutant ( , bottom) around the POA-binding site. The area of prominent change is boxed. b Structural and molecular nature of RpsACTD–POA interactions. Electrostatic potential surface representation of the MtRpsACTD–POA complex (left) and a close-up view of the ligand-binding site (right). A color-code bar shows an electrostatic scale from −77 to +77 eV. c Trans-translation provides bacteria with quality control over the translation process, through rescuing stalled ribosomes and cleaning up the incomplete polypeptides. The Alanyl-tmRNA/SmpB/EF-Tu complex first recognizes stalled ribosomes at the 3′-end of an mRNA. Translation is then resumed using tmRNA as a message, thereby adding a tmRNA-encoded peptide tag to the C-terminus of the stalled polypeptide. The tagged protein and mRNA are later degraded by specific proteases and RNases, respectively. PZA is first converted to the active form POA by pyrazinamidase (PZase) present in the M. tuberculosis cytoplasm. POA binds to RpsA, thus interfering with the interaction between RpsA with tmRNA required for trans-translation. The inhibition of POA on trans-translation may lead to failure in rescuing stalled ribosome thus depleting the ribosome pool, and accumulation of incomplete toxic proteins, causing cell death following stresses. Images are reproduced from (Shi et al. 2011) and (Yang et al. 2015) with permission (color figure online)

Evolution of fitness mutations

Drug resistances acquired from chromosomal mutations are often associated with a “fitness cost,” which affects the development, stability and domination of the emerging resistance mutants (Andersson 2006; Andersson and Hughes 2010; Andersson and Levin 1999). Indeed, drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains have been circulated mainly among AIDS patients, raising the perspective that resistance might be restricted within that community. However, studies using mathematical modeling, or those carried out with other organisms, first predicted that the fitness cost of drug resistant M. tuberculosis strains could be neutralized by “compensatory mutations,” secondary mutations that correct the fitness to the mutants (Andersson and Hughes 2010; Reynolds 2000; Sergeev et al. 2012). In vitro studies later strengthened the hypothesis that drug-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates are able to restore their fitness after prolonged exposure to antibiotics (Gagneux et al. 2006; Gillespie et al. 2002). However, the nature and molecular mechanisms of the observed fitness restoration had remained unknown until recently when a study by Comas et al. used whole-genome sequencing to map for genetic changes occurred in the fitness restored strains. This study identified a set of “compensatory mutations” in the genes encoding for the RNA polymerase in rifampicin-resistant strains (Comas et al. 2012). The fact that these mutations restore fitness to the rifampicin-resistant strains was confirmed by in vitro growth competition assays. Interestingly, these mutations were found in 30 % of MDR M. tuberculosis strains isolated from regions of MDR TB prevalence (Comas et al. 2012). Thus, the compensatory evolution might have helped to stabilize the epidemic of resistant strains following their primary emergence.

The arrival of totally drug-resistant (TDR) M. tuberculosis strains was finally confirmed, giving birth to a virtually untreatable form of TB (Dorman and Chaisson 2007; Ormerod 2005; Udwadia 2012). Similar to the MDR and XDR cases previously reported, the emergence of TDR TB is quite inevitable with the nonstop increase in anti-TB drug use. The crucial matter is whether or not compensatory evolution will allow stabilizing of the transmission of these drug resistant strains. If that is the case, the coevolution of drug resistance and fitness in M. tuberculosis will pose a deadly menace to humanity in the near future.

Intrinsic resistance

Mycobacterium tuberculosis has evolved multiple molecular mechanisms that allow for neutralizing the cytotoxicity of most toxic chemicals including antibiotics (Morris et al. 2005). These intrinsic resistance mechanisms provide the TB bacillus with a high background of drug resistance, which not only limits the use of existing antibiotics but also makes the development of new drugs more difficult. The following mechanisms all contribute to the overall intrinsic multidrug resistance of M. tuberculosis and related pathogenic mycobacteria.

Cell wall permeability

Similar to that of Gram-negative bacteria, the low permeable cell wall of mycobacteria functions as an effective barrier for drug penetration, representing an obstacle for antibiotic development. Penetration of β-lactams, for example, through the mycobacterial cell wall is 100-fold slower than going through the E. coli cell wall (Chambers et al. 1995; Kasik and Peacham 1968). Despite being classified as acid-fast Gram-positive bacteria, the mycobacterial cell wall is extremely thick and multilayered, creating a middle space similar to the periplasm in Gram-negative bacteria (Hoffmann et al. 2008; Zuber et al. 2008). The innermost layer of peptidoglycan is covered by a layer of arabinogalactan, both of which are hydrophilic thus hindering the penetration of hydrophobic molecules (Brennan and Nikaido 1995). These two layers are covalently linked to mycolic acids, long-chain fatty acids that form a hydrophobic barrier restricting the entry of hydrophilic molecules (Liu et al. 1995).

Role of the mycobacterial cell wall in the intrinsic antibiotic resistance is well studied using mutants defective in cell wall biosynthesis. Work by Liu and Nikaido first identified a mycolate defective M. smegmatis mutant, which displayed enhanced chemical uptake and sensitivity to rifampicin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin and novobiocin (Liu and Nikaido 1999). Transposon mutagenesis studies later confirmed the role of the cell wall in the intrinsic mycobacterial resistance (Gao et al. 2003; Philalay et al. 2004). For example, insertions in genes involved in mycolate biosynthesis such as kasB or the virS-mymA operon (rv3082 to rv3089) led to increased chemical penetration and sensitivity to rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ciprofloxacin (Gao et al. 2003; Singh et al. 2003, 2005). Ligation of mycolates to arabinogalactan or trehalose moieties in the cell wall is catalyzed by a family of redundant mycolyltransferases, also known as “the antigen 85 complex” or fibronectin-binding proteins (FbpA, FbpB and FbpC) (Belisle et al. 1997). Deletion of fbpA results in reduced cellular levels of trehalose di-mycolates (TDMs) and increased sensitivity to multiple antibiotics widely used for antibacterial chemotherapy (Nguyen et al. 2005). Despite the slow penetration through the mycobacterial cell wall, the extremely long doubling time of M. tuberculosis allows some antibiotics to accumulate at inhibitory levels well before cell division occurs, thus making cell wall permeability important but not central to the intrinsic drug resistance (Brennan and Nikaido 1995; Chambers et al. 1995; Quinting et al. 1997).

To uptake nutrients and small molecules, mycobacteria use porins, which are mounted to outer layers of the cell wall (Niederweis 2003). These porins facilitate the import of antibiotics through the outer layer of the mycobacterial cell wall, thus affecting drug resistance (Danilchanka et al. 2008). In trans expression of the major porin MspA from M. smegmatis reduced the resistance of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis to isoniazid, ethambutol, streptomycin and β-lactam antibiotics (Stephan et al. 2004). Conversely, deletion of mspA or mspC in M. smegmatis increased resistance to not only hydrophilic but also hydrophobic antibiotics including rifampicin, vancomycin and erythromycin (Danilchanka et al. 2008; Stephan et al. 2004). Although M. tuberculosis encodes at least two porin-like proteins, OmpA, encoded by rv0899, and Rv1698 (Senaratne et al. 1998; Siroy et al. 2008), which expression restores antibiotic sensitivity to the M. smegmatis mspA mutant (Siroy et al. 2008), the role of the M. tuberculosis porins in antibiotic uptake and susceptibility remains elusive.

Specialized resistance mechanisms

While the mycobacterial cell wall slows down antibiotic penetration (Nikaido 1994), specialized resistance mechanisms help to detoxify drug molecules that manage to reach the cytoplasmic space.

Target alteration

One of the strategies that bacteria utilize to avoid action of antibiotics is to modify the structure of drug targets, thereby reducing antibiotic binding. This mechanism is used by M. tuberculosis and related mycobacteria to reduce binding of macrolides and lincosamides to their ribosomes. These drugs bind reversibly to a specific site of the ribosomal RNA within the 50S subunit of bacterial ribosomes, thus inhibiting translocation of peptidyl-tRNA (Buriankova et al. 2004). This activity suppresses protein synthesis, thereby inhibiting growth. Mycobacterial species including M. tuberculosis and M. bovis are naturally resistant to macrolides and lincosamides. Interestingly, the Pasteur vaccine strain BCG (Bacillus of Calmette and Guérin) derived from M. bovis is uniquely susceptible to these antibiotics. Comparative genomics revealed a chromosomal deletion causing the loss of the erm37 (or rv1988) gene in the BCG genome (Buriankova et al. 2004). erm37, encoding a ribosomal RNA methyltransferase, is located within a larger chromosomal locus known as the RD2 (Region of Difference 2) which was deleted in BCG during its culture passage. The intrinsic resistance to macrolides and lincosamides could be restored to BCG by in trans expression of the M. tuberculosis erm37 (Buriankova et al. 2004), which alters ribosomal structures by methylating the 23S ribosomal RNA (Madsen et al. 2005). This reduces the affinity of macrolides to ribosomes, thus lowering the inhibitory activity of the drug on protein synthesis (Buriankova et al. 2004). Other erm genes conferring macrolide and lincosamide resistance were found in M. smegmatis and M. fortuitum (Nash 2003; Nash et al. 2005), whose expressions are inducible by exposure to macrolides and lincosamides (Andini and Nash 2006; Nash 2003; Nash et al. 2005). The inducible expression of Erm37 was later found to be regulated by the MDR transcription regulator WhiB7 (Burian et al. 2012, 2013; Morris et al. 2005), which is discussed elsewhere in this chapter. These studies suggest that the function of Erm37 and related ribosomal RNA methyltransferase is specialized for macrolide and lincosamide resistance in mycobacteria. Interestingly, a more recent study showed that Erm37, besides its role in protecting the mycobacterial ribosome from macrolides and lincosamides, is also involved in an epigenetic mechanism hijacking host macrophages’ gene expression control. In this study, Erm37 was shown to be secreted by M. tuberculosis and localized to the host nucleus where it interacts with chromatin and methylates histone H3 at H3R42, repressing the expression of genes involved in the first-line defense against pathogenic mycobacteria (Yaseen et al. 2015). The antibiotic-induced expression of mycobacterial factors such as Erm37 or Eis (see “Drug inactivation” below), which are involved in both virulence and drug resistance, represents a dangerous evolution of infectious diseases against antibiotic chemotherapies.

A similar mechanism is used by M. tuberculosis to neutralize activity of cyclic peptide antibiotics such as capreomycin and viomycin, which are commonly used to treat MDR TB. Studies in M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis mapped resistance mutations to tlyA that encodes a 2′-O-methyltransferase whose activity correlates with capreomycin and viomycin resistance (Maus et al. 2005). TlyA methylates both 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA at nucleotide C1409 and C1920, respectively (Johansen et al. 2006), thereby rendering ribosomes susceptible to the binding of capreomycin and viomycin (Johansen et al. 2006; Maus et al. 2005).

Target mimicry

Molecular mimicry is a fascinating mechanism employed by M. tuberculosis to neutralize the action of fluoroquinolones, synthetic antibiotics that have recently become important for treating drug resistant TB cases (Duncan and Barry 2004). Fluoroquinolones are bactericidal drugs that kill bacterial cells by inhibiting DNA replication, transcription and repair. These antibiotics bind DNA gyrase or topoisomerase in their complexes with DNA, thereby stabilizing breaks while inhibiting resealing of the DNA strands. These events eventually result in DNA degradation and cell death (Andriole 2005).

Whereas acquired fluoroquinolone resistance is commonly mapped to mutations in DNA gyrase-encoded genes gyrA and gyrB, in M. tuberculosis (Table 1), its intrinsic resistance is attributed to a pentapeptide repeat protein called MfpA. A study in M. smegmatis and M. bovis first found that expression of MfpA correlates with fluoroquinolone resistance (Montero et al. 2001). MfpA is most homologous to pentapeptide repeat proteins, within the sequences of which every fifth amino acid is either leucine or phenylalanine. When the structure of the M. tuberculosis MfpA was resolved, it was found that it closely resembles the 3D structure of a DNA double helix (Ferber 2005; Hegde et al. 2005), with tandems of pentapeptide repeats coiling around in a right-handed helix of the same width as DNA (Hegde et al. 2005; Morais Cabral et al. 1997). It was proposed that MfpA sequesters fluoroquinolones in the mycobacterial cytoplasm by mimicking the DNA structure, thus freeing DNA from the drug’s action (Ferber 2005). Although the physiological function of MfpA and its significance in fluoroquinolone resistance remain unknown, this finding reveals a fascinating mechanism that bacterial pathogens may use to avoid succumb to antibiotics.

Drug modification

Mycobacterial species can also directly inactivate drugs through chemical modifications such as acetylation. Aminoglycosides are broad-spectrum antibiotics that constitute an important position in the history of TB treatment. While streptomycin was the first effective antibiotic for TB, kanamycin and amikacin are second-line drugs that are commonly used to treat MDR TB cases. Resistance to these drugs in MDR strains is the hallmark to define XDR TB. The precise mode of action of aminoglycosides remains to be understood although they are thought to act mainly as inhibitors of protein synthesis. The intrinsic resistance of M. tuberculosis to aminoglycosides is provided by an acetyltransferase (Zaunbrecher et al. 2009) termed Eis (enhanced intracellular survival), which was initially found to play a role in mycobacterial survival in host macrophages (Wei et al. 2000). This protein was more recently found to play an important role in manipulating the host innate immunity against mycobacterial infection. Eis is secreted by M. tuberculosis to the infected macrophage’s cytosol where it acetylates MKP7, a host phosphatase that regulates the phosphorylation status of the protein kinases JNK and p38 of the MAPK pathway. These modulations on the host signaling lead to the suppression of host immune responses, namely autophagy, inflammation and apoptosis, to mycobacterial infection (Kim et al. 2012).

In a screen for aminoglycoside resistance determinants, a cosmid library was constructed from the genomic DNA of a kanamycin-resistant M. tuberculosis strain (Zaunbrecher et al. 2009), then transformed to a susceptible strain and selected for kanamycin resistance. Mapping of the cosmid conferring kanamycin resistance identified mutations within the promoter region of eis, whose expression was previously found to be regulated by the MDR transcription regulator WhiB7 (Burian et al. 2012, 2013; Morris et al. 2005). The mutations, which were later found in 80 % of low-level kanamycin-resistant isolates (Campbell et al. 2011; Engstrom et al. 2011; Zaunbrecher et al. 2009), as well as in MDR strains (Huang et al. 2011), increased eis transcription by 180-fold (Zaunbrecher et al. 2009). In vitro biochemical studies showed that Eis acetylates multiple amine groups of aminoglycosides using acetyl coenzyme A as an acetyl donor (Chen et al. 2011), thereby inactivating the antibiotics. A recent study further suggested that Eis acetylates not only aminoglycosides but also capreomycin, a cyclic peptide antibiotic now commonly used to treat MDR TB (Houghton et al. 2013). The fact that Eis dually functions in protecting mycobacteria against both the host immunity and antibiotics implies a sinister coevolution of virulence and antibiotic resistance in M. tuberculosis.

Drug degradation

Another method that bacterial pathogens including M. tuberculosis use to subvert antibiotics’ action is to degrade them using hydrolases. This mechanism is well studied in the case of β-lactams, drugs that have virtually no effect on M. tuberculosis and related mycobacteria. These antibiotics bind and inhibit penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are required for the assembly of the peptidoglycan network, thereby disrupting cell wall synthesis and causing cell death. The genome of M. tuberculosis encodes at least four major PBPs, all of which bind β-lactams at clinically achievable concentrations (Chambers et al. 1995), indicating that low target affinity is not the cause of β-lactam resistance in mycobacteria. Target accessibility due to the impermeable cell wall, however, plays a clear role in mycobacterial β-lactams resistance. In this regard, the long generation time of M. tuberculosis serves as both pros and cons to the bacillus’ resistance. Carbapenems, for example, are rather unstable and therefore loose activity much faster compared with the mycobacterial growth rate. Nevertheless, continued intakes from daily regimens could still allow sufficient accumulation to lethal concentrations that inhibit the slow cell division machinery (Watt et al. 1992).

For β-lactams, the paramount resistance determinant was shown in mycobacteria to be β-lactamases, hydrolytic enzymes that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring of the drugs (Chambers et al. 1995). This knowledge is mostly obtained from studies in M. fallax, a Mycobacterium species uniquely β-lactam susceptible (Kasik 1979; Quinting et al. 1997). Permeability assays demonstrated that β-lactams penetrate through the M. fallax cell wall at rates which (a) are similar to those of other mycobacteria and (b) should allow accumulation of β-lactams to lethal concentrations (Quinting et al. 1997). When M. fallax was engineered to in trans express a β-lactamase from M. fortuitum, its resistance immediately increased to levels comparable to other species (Quinting et al. 1997), indicating that a lack of effective β-lactamases underlies the bacillus’ β-lactam susceptibility. Although mycobacterial β-lactamases are generally less effective than those of other pathogenic bacteria, the slow penetration of β-lactams across their impermeable cell wall renders this low β-lactamase activity good enough to protect mycobacteria from β-lactams (Jarlier et al. 1991).

BlaC, the most important β-lactamase in M. tuberculosis, belongs to the Ambler class A β-lactamases, of which enzymatic activities and structures have been thoroughly studied (Voladri et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2006). Possibly due to its large and flexible substrate-binding site (Wang et al. 2006), BlaC exhibits broad substrate specificity, including carbapenems that generally are β-lactamases-resistant (Hugonnet and Blanchard 2007; Tremblay et al. 2010). β-Lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid are also less effective against BlaC than to other class A enzymes. Expression of BlaC in M. tuberculosis is controlled by BlaI, a β-lactam-induced, winged-helix transcription repressor. In the absence of β-lactams, BlaI forms homodimers that bind the promoter of blaC, thereby inhibiting its transcription (Sala et al. 2009). When M. tuberculosis is exposed to β-lactams, BlaI dissociates from its DNA binding site, thus derepressing blaC transcription and leading to β-lactamase production (Sala et al. 2009).

In addition to BlaC, M. tuberculosis encodes at least three more β-lactamases, BlaS, Rv0406c and Rv3677c, which provide lower β-lactamase activities (Flores et al. 2005; Nampoothiri et al. 2008).

Drug efflux

A method commonly used by bacterial pathogens to avoid succumbing to antibiotics is to expel them from the cytoplasm through efflux pumps. These transmembrane proteins usually play roles in antibiotic-unrelated physiology or metabolism, such as transporting nutrients, wastes, toxins or signaling molecules across the cell wall. Their functions in antibiotic resistance may be secondary due to non-specific transport activities. For examples, 20 out of the total of 36 genes encoding membrane transport proteins in the E. coli genome confer some levels of resistance to one or more antibiotics (Nishino and Yamaguchi 2001). It is unlikely that all these transporters have evolved to become specialized drug transporters. Instead, what have evolved are likely regulatory proteins that control these transporters’ expression, thereby specializing their function toward drug resistance. For example, the major E. coli MDR determinant AcrB is a transporter with a broad substrate specificity, but its expression is controlled by three antibiotic-responsive regulatory systems: Mar, Sox and Rob (Alekshun and Levy 1997).

At least 18 transporters in mycobacteria have been found to confer low-level antibiotic resistance (Viveirosa et al. 2012). Some of these transporters are expressed under the control of antibiotic-responsive transcription regulators. For example, expression of IniBAC and EfpA are negatively regulated by Lsr2, a nucleoid-associated transcription regulator that binds AT-rich sequences (Colangeli et al. 2007). Whereas IniBAC confers resistance to isoniazid and ethambutol, EfpA provides non-specific transport (Colangeli et al. 2005, 2007). Importantly, the transcriptional control of iniBAC and efpA by Lsr2 is inducible by isoniazid or ethambutol (Colangeli et al. 2007), thus specializing these transporters’ function to antibiotic resistance. Besides drug resistance, recent studies suggested that Lsr2 is involved in mycobacterial adaptation to changes in oxygen level, and persistence in hosts (Bartek et al. 2014), thus connecting antibiotic resistance and the pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis.

Another example is Tap, a transporter responsible for mycobacterial efflux of aminoglycosides, spectinomycin, tetracycline and PAS (Ainsa et al. 1998; Morris et al. 2005; Ramon-Garcia et al. 2012). Transcription of the Tap-encoding gene (rv2158c) is controlled by the antibiotic-responsive MDR regulator WhiB7 (Ainsa et al. 1998; Morris et al. 2005; Ramon-Garcia et al. 2012). A recent study showed that expression of several efflux pumps including Tap is induced in mycobacterial cells residing within host granulomas, indicating that these molecular pumps may contribute to the drug tolerance of M. tuberculosis during latent TB (Adams et al. 2011). For more information on mycobacterial transporters and their role in antibiotic resistance, readers are referred to many recent excellent reviews (da Silva et al. 2011; Viveirosa et al. 2012).

Bactericidal activity of drugs and oxidative stress in mycobacteria

Work with E. coli and Salmonella first established the cellular correlation between antibiotic resistance and oxidative stress (Demple 2005), both of which are controlled by the same regulatory proteins such as SoxRS, MarRAB or Rob. Although the clear reason for this functional overlap remains elusive, it is highly conserved and believed to have evolved to provide bacteria with effective defense mechanisms against general stresses (Demple 2005). Recent studies, which established the connections between the bactericidal activity of antibiotics and oxidative stress (Kohanski et al. 2010a, b, 2007), may help to explain the evolution of regulatory systems toward simultaneous coping with these two environmental threats. Exposure of E. coli to bactericidal antibiotics induces cellular production of hydroxyl radicals, which is mediated through complex sequential events starting from the NADH molecule produced by TCA cycle (Kohanski et al. 2007). NADH is oxidized via complex electron transport chains leading to the production of superoxide, which damages iron–sulfur clusters and donates ferrous iron to the oxidation of Fenton reaction. Hydroxyl radicals produced from Fenton reaction then damage DNA, proteins and lipids, resulting in cell death (Fig. 1) (Kohanski et al. 2007). Thus, the controlled induction of drug resistance proteins in parallel with proteins involved in resistance to hydroxyl radicals may provide a better defense against bactericidal antibiotics.

The relationship between antibiotic resistance and oxidative stress in mycobacteria was first noticed through studies that showed activation of the prodrugs isoniazid and ethionamide by oxidative stress proteins such as KatG and AhpC (Sherman et al. 1996; Zhang et al. 1992, 1996). It was also found that expression of the stress-responsive sigma factor F (SigF) is induced by antibiotics (Michele et al. 1999) and that mycothiol, the thiol molecule mycobacteria use to defense against oxygen toxicity, is also required for antibiotic resistance (Buchmeier et al. 2003; Rawat et al. 2002; Vilcheze et al. 2008). Work with the MDR systems Lsr2 and WhiB7 further demonstrated the interrelationship between redox homeostasis and antibiotic resistance (Burian et al. 2012; Colangeli et al. 2009; Morris et al. 2005). While previous work found that Lsr2 regulates expression of the drug efflux pump IniBAC (Colangeli et al. 2005, 2007), more recent studies suggested that Lsr2 also protects M. tuberculosis from oxidative stress (Bartek et al. 2014; Colangeli et al. 2009). WhiB7 is a MDR transcription regulator exclusively found in Actinobacteria including mycobacteria (Morris et al. 2005; Ramon-Garcia et al. 2013). Deletion of whiB7 leads to increased sensitivity to multiple antibiotics whereas overexpression results in enhanced resistance (Morris et al. 2005). M. tuberculosis WhiB7, a 122-amino acid protein carrying an iron–sulfur cluster, regulates transcription of multiple antibiotic resistance genes including eis, erm37 and tap that are discussed elsewhere in this paper. Expression of whiB7 and its regulon is regulated in response to not only antibiotics such as erythromycin and tetracycline but also oxidoreductive reagents such as dithiothreitol and diamide (Burian et al. 2012; Morris et al. 2005), indicating the correlation of the WhiB7-mediated intrinsic multidrug resistance and cellular redox status. In addition to Lsr2 and WhiB7, another mycobacterial MDR determinant, the function of which was found to link to oxidative stress and the TCA cycle, was recently reported. The eukaryotic-like protein kinase G (PknG) was first found to function as a virulence factor required for the survival of pathogenic mycobacteria in host macrophages (Walburger et al. 2004). Surprisingly, PknG was recently found also to affect the intrinsic multidrug resistance in mycobacteria (Wolff et al. 2009). Although the precise mechanism underlying the role of PknG in mycobacterial multidrug resistance remains to be understood, the involvement of this kinase in controlling the TCA cycle and the cellular NADH level might provide an explanation (Fig. 1). Together with some other kinases, Corynebacterium glutamicum PknG phosphorylates OdhI, an inhibitor of 2-oxozglutarate dehydrogenase (ODH) that catalyzes the NAD+-dependent conversion of 2-oxoglutarate (or α-ketoglutarate) to succinyl CoA in the TCA cycle (Niebisch et al. 2006; O’Hare et al. 2008). Phosphorylated OdhI can no longer inhibit ODH, thus allowing the continuation of the TCA cycle (Niebisch et al. 2006). In M. tuberculosis, the TCA cycle lacks ODH activity. Instead, α-ketoglutarate is first converted to succinic semialdehyde by α-ketoglutarate decarboxylase (KGD), and then further converted to succinate (Fig. 1) (Tian et al. 2005). The M. tuberculosis OdhI homolog, GarA, inhibits KGD and NAD+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), but enhances glutamate synthase (GS) activity (Chao et al. 2010; Nott et al. 2009). Similar to C. glutamicum OdhI, GarA is phosphorylated by multiple mycobacterial kinases including PknG (O’Hare et al. 2008), and phosphorylated GarA looses its regulatory functions. The enzymes controlled by GarA also interconvert the two forms of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NADH and NAD+, as their cofactors (Fig. 1). Through its regulation on GarA, PknG therefore affects the cellular pool of NADH. Interestingly, PknG was recently found to control a redox homeostatic system, RHOCS, which regulates cellular NADH level through a Nudix hydrolase that specifically degrades NADH (Wolff et al. 2015). It remains to be established if PknG affects the bactericidal activity of anti-TB drugs through its regulation of NADH and the consequent production of radicals leading to cell death (Fig. 1) (Kohanski et al. 2007, 2010b).

Phenotypic tolerance

Whereas both the intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms are genetically defined by genes or mutations directly involved with drug resistance, phenotypic tolerance is associated with metabolic or physiological changes that are not directly related to antibiotic resistance genes. This epigenetic drug tolerance refers to the formation of “persisters,” a small subpopulation of cells with distinct but poorly defined metabolic or physiological states. These cells are genetically identical with their susceptible counterparts and convertible back into susceptible cells when the “normal” environment is restored (Lewis 2008).

A resistance mechanism generally results in reduced access of an antibiotic to its target whereas tolerance is associated with lowering metabolic activities, thus reducing the cellular requirement for the protein target (Lewis 2008). Access and inhibition of the antibiotic to its target may occur normally, but the inhibitory action is no longer lethal to those persister cells (Lewis 2008). Once persisters resume active growth, the cellular requirement for the protein target is back to normal, thus re-sensitizing the now metabolically active cells to the antibiotic. During its latent infection, M. tuberculosis is believed to enter a dormant-like state characterized by a shutdown of most of its metabolism, leading to increased antibiotic tolerance (Gengenbacher and Kaufmann 2012; Gomez and McKinney 2004). Indeed, M. tuberculosis cells directly isolated from patients with latent or relapsed TB showed increased tolerance to rifampicin, isoniazid and ethambutol compared with those isolated from drug-sensitive patients, though the tolerance was strictly phenotypic (Wallis et al. 1999). Transcriptomics analyses of these TB persisters, which replicate extremely slowly or completely stop growth, showed that the drug tolerance is due to low metabolic rates rather than resistance mutations (Garton et al. 2008).

In vitro models

The formation of dormant-like M. tuberculosis cells can be induced in vitro by introducing environmental stresses that likely trigger latent TB in vivo. The earliest method is called the Wayne model in which oxygen is gradually removed resulting in a stepwise transition from actively growing M. tuberculosis cells to dormant cells that display very low metabolic activities but increased drug tolerance (Wayne and Hayes 1996). Nutrient starvation or antibiotics such as D-cycloserine also induce the formation of non-replicating M. tuberculosis cells, which exhibit reduced respiration and metabolism but enhanced multidrug tolerance (Betts et al. 2002; Xie et al. 2005). Whereas persisters obtained from these models all share certain features, such as reduced cellular ATP level and increased lipid metabolism, other features may be specific for each system depending on inducers (Gengenbacher and Kaufmann 2012; Keren et al. 2011). These in vitro studies helped to establish the relationship between phenotypic drug tolerance and low metabolic activity during the dormancy of M. tuberculosis in hosts.

Even without any stimulus, a smaller fraction of bacterial cells growing in vitro steadily converts to persister-like cells, with frequencies increasing when cultures reach stationary phase (Hansen et al. 2008; Keren et al. 2004, 2011; Lewis 2008). Thus, the formation of persisters seems to be an intrinsic characteristic of bacterial populations, creating cell heterogeneity. Perhaps, persisters are cells that are designated to sacrifice growth, so that to ensure the survival of the population in disastrous conditions including antibiotic exposure (Keren et al. 2004; Lewis 2008).

In vivo models

While it is extremely difficult to study M. tuberculosis persisters residing within granulomas during TB infection of humans, animal models have helped to better understand how M. tuberculosis enters and exits persistence. For example, the Cornell mouse model, originally described in the 1950s, uses isoniazid or pyrazinamide to treat infected mice until the mice show no sign of active disease and no bacilli detected in the infected organs (McCune et al. 1956; McCune and Tompsett 1956). Disease reactivation may occur spontaneously by ceasing treatment or by triggering with immune-suppressors, confirming that drug-tolerant persisters are formed during the antibiotic treatment (McCune et al. 1956; McCune and Tompsett 1956; Scanga et al. 1999). A similar model, in which mice were infected with transposon M. tuberculosis mutants, was successfully used to screen for isoniazid persistence genes (Dhar and McKinney 2010).

Molecular mechanisms

The precise mechanisms underlying the formation of drug-tolerant persisters in vivo remain largely unknown although studies have indicated the involvement of toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems. These paired proteins provide bacteria with a sensitive and fast modulated method to influence the expression of a large numbers of genes involved in metabolic pathways. While “toxin” proteins suppress metabolism by inhibiting the replication or translation of the genes involved, “antitoxin” proteins neutralize the inhibitory activity of the toxins, thereby derepressing metabolism (Lewis 2008). TA modules therefore provide strict control over metabolism, thus allowing safe entry or exit from persistence (Keren et al. 2004, 2011). While the E. coli genome encodes about 20, M. tuberculosis has more than 65 TA pairs (Keren et al. 2011), many of which have been shown to play a role in drug tolerance and dormancy. For example, the induction of M. tuberculosis persister formation by D-cycloserine upregulates 10 TA modules, among which is the toxin Rv2866 [TA pair Rv2865–Rv2866], a homolog of the E. coli mRNA endonuclease RelE that induces dormancy through shutting down translation (Keren et al. 2004, 2011). Similarly, VapC, the toxin component of the TA pair VapC–VapBC, binds and cleaves specific RNA, thus reducing activities of the related metabolism (McKenzie et al. 2012; Sharp et al. 2012). Another example is the TA pair Rv1102c–Rv1103c, in which the toxin Rv1102c functions as a ribonuclease whereas the antitoxin Rv1103c binds and inactivates Rv1102c (Han et al. 2010). When Rv1102c was expressed in M. smegmatis without its antitoxin, growth was arrested leading to the formation of persister-like cells, which displayed high tolerance to kanamycin and gentamycin (Han et al. 2010).

Inorganic polyphosphate may also play a role in converting M. tuberculosis from a vegetative drug-sensitive state to a dormant drug-tolerant state (Thayil et al. 2011), possibly through inducing RpoS, the sigma factor that regulates the expression of around 50 genes responsible for down-regulating metabolism and cell division (Hengge-Aronis 2002; Shiba et al. 1997). The involvement of phosphate in M. tuberculosis persister formation is also supported by the study of PhoY2, which functions as a negative regulator of phosphate uptake, similar to the persistence switch PhoU in E. coli (Li and Zhang 2007; Shi and Zhang 2010).

Efflux pumps may also contribute to the increased drug tolerance of mycobacterial cells persisting within hosts. Infection of zebrafish with M. marinum followed by treatment with anti-TB drugs results in the emergence and enrichment of a population of multidrug-tolerant bacilli, which later disseminate into granulomas (Adams et al. 2011). Interestingly, the drug tolerance level of these bacilli reduced when efflux pump inhibitors were added to the regimens, indicating the involvement of efflux pumps in drug persistence (Adams et al. 2011).

Conclusions and perspectives

The discovery of antibiotics has been one of the greatest advancements in modern medicine. These “magic bullets” have saved millions of lives since the beginning of the twentieth century and fundamentally changed the way we treat bacterial infections (Nguyen 2015). Compared with the pre-antibiotic period that dated back thousands of years, during which infectious diseases might have shaped human evolution (Wang et al. 2012), the current antibiotic era has been less than a hundred of years. Although it is relatively short, this time period has completely changed the coevolution between humans and our bacterial pathogens. Human individuals susceptible to certain infections no longer have to die while bacteria now must evolve under an additional selective pressure that is to survive against antibiotics. Bacterial pathogens including M. tuberculosis have survived by progressively gaining antibiotic resistance. Newly acquired mutations arisen in genes encoding target proteins or those required for drug activities have allowed bacteria to rapidly evolve toward antibiotic resistance. Sequential chromosomal accumulation of such mutations has resulted in the formation of M. tuberculosis strains that are increasingly resistant to available antibiotics. Importantly, multidrug resistant strains can further evolve to regain fitness by acquiring compensatory mutations, thus stabilizing transmissibility.

By nature, M. tuberculosis is already endowed with a profound resistance level to most antibiotics. The intrinsic drug resistance of M. tuberculosis is composed of both passive and specialized mechanisms, the latter of which often act in response to antibiotics. How have these system evolved to recognize and respond to antibiotics are unknown, but the proteins directly responsible for resistance might have probably existed long before antibiotics were used, serving physiological or metabolic functions (D’Costa et al. 2006, 2011). While these structural “drug resistance proteins” may still play roles in the physiology or metabolism of bacteria including M. tuberculosis, the evolved inducibility of gene expression allows their activities to be specialized for antibiotic resistance. In this regard, the evolution of regulatory systems toward antibiotic responsiveness might play a key role in specializing the function of drug resistance proteins.

In addition to the two types of drug resistance mechanisms discussed above, the metabolic transition of M. tuberculosis from active growth to dormancy leads to phenotypic tolerance, reflected by the therapeutic recalcitrance observed in latent TB. These resistance and tolerance mechanisms not only limit the application of available antibiotics but also impede the development of new drugs. Knowledge of these mechanisms may facilitate the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies that compromise the drug resistance of M. tuberculosis (Nguyen 2012).

Acknowledgments

Work in the Nguyen laboratory is supported by NIH Grants R01AI087903 and R21AI119287.

References

- Adams KN, Takaki K, Connolly LE, et al. Drug tolerance in replicating mycobacteria mediated by a macrophage-induced efflux mechanism. Cell. 2011;145(1):39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adilakshmi T, Ayling PD, Ratledge C. Mutational analysis of a role for salicylic acid in iron metabolism of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(2):264–271. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.264-271.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsa JA, Blokpoel MC, Otal I, Young DB, De Smet KA, Martin C. Molecular cloning and characterization of Tap, a putative multidrug efflux pump present in Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(22):5836–5843. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5836-5843.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Regulation of chromosomally mediated multiple antibiotic resistance: the mar regulon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41(10):2067–2075. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DC, Ma JH, Guthrie JL, Blair J, Chedore P, Jamieson FB. Gene sequencing for routine verification of pyrazinamide resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a role for pncA but not rpsA. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3726–3728. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00620-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DI. The biological cost of mutational antibiotic resistance: any practical conclusions? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9(5):461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DI, Hughes D. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(4):260–271. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DI, Levin BR. The biological cost of antibiotic resistance. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2(5):489–493. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andini N, Nash KA. Intrinsic macrolide resistance of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex is inducible. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(7):2560–2562. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00264-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriole VT. The quinolones: past, present, and future. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 2):S113–S119. doi: 10.1086/428051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamaga M, Wright DJ, Zhang H. Selection of in vitro mutants of pyrazinamide-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;20(4):275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartek IL, Woolhiser LK, Baughn AD, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Lsr2 is a global transcriptional regulator required for adaptation to changing oxygen levels and virulence. MBio. 2014;5(3):e01106–e01114. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01106-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belisle JT, Vissa VD, Sievert T, Takayama K, Brennan PJ, Besra GS. Role of the major antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cell wall biogenesis. Science. 1997;276(5317):1420–1422. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim F. The effect of salicylate on the oxygen uptake of the tubercle bacillus. Science. 1940;92(2383):204. doi: 10.1126/science.92.2383.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts JC, Lukey PT, Robb LC, McAdam RA, Duncan K. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43(3):717–731. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum M, Koch R, Brendecke F. Prof Koch’s method to cure tuberculosis popularly treated. H.E. Haferkorn; Milwaukee: 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Boshoff HI, Mizrahi V. Expression of Mycobacterium smegmatis pyrazinamidase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis confers hypersensitivity to pyrazinamide and related amides. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(19):5479–5485. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.19.5479-5485.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PJ, Nikaido H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier NA, Newton GL, Koledin T, Fahey RC. Association of mycothiol with protection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from toxic oxidants and antibiotics. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47(6):1723–1732. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burian J, Ramon-Garcia S, Sweet G, Gomez-Velasco A, Av-Gay Y, Thompson CJ. The mycobacterial transcriptional regulator whiB7 gene links redox homeostasis and intrinsic antibiotic resistance. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(1):299–310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.302588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burian J, Yim G, Hsing M, et al. The mycobacterial antibiotic resistance determinant WhiB7 acts as a transcriptional activator by binding the primary sigma factor SigA (RpoV) Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(22):10062–10076. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buriankova K, Doucet-Populaire F, Dorson O, et al. Molecular basis of intrinsic macrolide resistance in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(1):143–150. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.143-150.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PJ, Morlock GP, Sikes RD, et al. Molecular detection of mutations associated with first- and second-line drug resistance compared with conventional drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(5):2032–2041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01550-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Gruber T, Barry CE, 3rd, Boshoff HI, Rhee KY. Para-aminosalicylic acid acts as an alternative substrate of folate metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2013;339(6115):88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1228980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers HF, Moreau D, Yajko D, et al. Can penicillins and other β-lactam antibiotics be used to treat tuberculosis? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39(12):2620–2624. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J, Wong D, Zheng X, et al. Protein kinase and phosphatase signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804(3):620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Biswas T, Porter VR, Tsodikov OV, Garneau-Tsodikova S. Unusual regioversatility of acetyltransferase Eis, a cause of drug resistance in XDR-TB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(24):9804–9808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105379108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangeli R, Helb D, Sridharan S, et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis iniA gene is essential for activity of an efflux pump that confers drug tolerance to both isoniazid and ethambutol. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(6):1829–1840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangeli R, Helb D, Vilcheze C, et al. Transcriptional regulation of multi-drug tolerance and antibiotic-induced responses by the histone-like protein Lsr2 in M. tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(6):e87. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangeli R, Haq A, Arcus VL, et al. The multifunctional histone-like protein Lsr2 protects mycobacteria against reactive oxygen intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(11):4414–4418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810126106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas I, Borrell S, Roetzer A, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains identifies compensatory mutations in RNA polymerase genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(1):106–110. doi: 10.1038/ng.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett EL, Watt CJ, Walker N, et al. The growing burden of tuberculosis: global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(9):1009–1021. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Costa VM, McGrann KM, Hughes DW, Wright GD. Sampling the antibiotic resistome. Science. 2006;311(5759):374–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1120800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature. 2011;477(7365):457–461. doi: 10.1038/nature10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva PE, Von Groll A, Martin A, Palomino JC. Efflux as a mechanism for drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;63(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilchanka O, Pavlenok M, Niederweis M. Role of porins for uptake of antibiotics by Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(9):3127–3134. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzins E. The bacteriology of tuberculosis. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 1958. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- De Voss JJ, Rutter K, Schroeder BG, Su H, Zhu Y, Barry CE., 3rd The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(3):1252–1257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demple B. The nexus of oxidative stress responses and antibiotic resistance mechanisms in Escherichia coli and Salmonella. In: White DG, Alekshun MN, McDermott PF, Levy SB, editors. Frontiers in antimicrobial resistance: a tribute to Stuart B Levy. American Society for Microbiology; Washington: 2005. pp. 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar N, McKinney JD. Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence mutants identified by screening in isoniazid-treated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(27):12275–12280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003219107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman SE, Chaisson RE. From magic bullets back to the magic mountain: the rise of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2007;13(3):295–298. doi: 10.1038/nm0307-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K, Barry CE., 3rd Prospects for new antitubercular drugs. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7(5):460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom A, Perskvist N, Werngren J, Hoffner SE, Jureen P. Comparison of clinical isolates and in vitro selected mutants reveals that tlyA is not a sensitive genetic marker for capreomycin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(6):1247–1254. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber D. Biochemistry. Protein that mimics DNA helps tuberculosis bacteria resist antibiotics. Science. 2005;308(5727):1393. doi: 10.1126/science.308.5727.1393a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores AR, Parsons LM, Pavelka MS., Jr Genetic analysis of the beta-lactamases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis and susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics. Microbiology. 2005;151(Pt 2):521–532. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagneux S, Long CD, Small PM, Van T, Schoolnik GK, Bohannan BJ. The competitive cost of antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2006;312(5782):1944–1946. doi: 10.1126/science.1124410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao LY, Laval F, Lawson EH, et al. Requirement for kasB in Mycobacterium mycolic acid biosynthesis, cell wall impermeability and intracellular survival: implications for therapy. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49(6):1547–1563. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garton NJ, Waddell SJ, Sherratt AL, et al. Cytological and transcript analyses reveal fat and lazy persister-like bacilli in tuberculous sputum. PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e75. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengenbacher M, Kaufmann SH. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: success through dormancy. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36(3):514–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SH, Billington OJ, Breathnach A, McHugh TD. Multiple drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: evidence for changing fitness following passage through human hosts. Microb Drug Resist. 2002;8(4):273–279. doi: 10.1089/10766290260469534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez JE, McKinney JD. M. tuberculosis persistence, latency, and drug tolerance. Tuberculosis. 2004;84(1–2):29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JS, Lee JJ, Anandan T, et al. Characterization of a chromosomal toxin–antitoxin, Rv1102c–Rv1103c system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;400(3):293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]