Significance

Resting-state functional connectivity (FC) is a commonly used method in neuroimaging to noninvasively study network organization of brains in humans and other animals. FC is reproducible across different institutions and sensitive enough to detect network changes due to psychiatric disorders. FC is thus a core tool for projects such as the Human Connectome Project. However, because hemodynamic signals are an indirect measure of neuronal activity, actual spatiotemporal neuronal activity underlying FC is still unknown. This study used simultaneous wide-field optical imaging of neuronal calcium signals and hemodynamic signals in transgenic mice to understand the spatiotemporal neuronal dynamics underlying FC. Transient spatial patterns of neuronal coactivations embedded within waves of activity propagating across neocortex were found to be particularly important for FC.

Keywords: brain network, spontaneous activity, Ca imaging, optical imaging, fMRI

Abstract

Resting-state functional connectivity (FC), which measures the correlation of spontaneous hemodynamic signals (HemoS) between brain areas, is widely used to study brain networks noninvasively. It is commonly assumed that spatial patterns of HemoS-based FC (Hemo-FC) reflect large-scale dynamics of underlying neuronal activity. To date, studies of spontaneous neuronal activity cataloged heterogeneous types of events ranging from waves of activity spanning the entire neocortex to flash-like activations of a set of anatomically connected cortical areas. However, it remains unclear how these various types of large-scale dynamics are interrelated. More importantly, whether each type of large-scale dynamics contributes to Hemo-FC has not been explored. Here, we addressed these questions by simultaneously monitoring neuronal calcium signals (CaS) and HemoS in the entire neocortex of mice at high spatiotemporal resolution. We found a significant relationship between two seemingly different types of large-scale spontaneous neuronal activity—namely, global waves propagating across the neocortex and transient coactivations among cortical areas sharing high FC. Different sets of cortical areas, sharing high FC within each set, were coactivated at different timings of the propagating global waves, suggesting that spatial information of cortical network characterized by FC was embedded in the phase of the global waves. Furthermore, we confirmed that such transient coactivations in CaS were indeed converted into spatially similar coactivations in HemoS and were necessary to sustain the spatial structure of Hemo-FC. These results explain how global waves of spontaneous neuronal activity propagating across large-scale cortical network contribute to Hemo-FC in the resting state.

Resting-state functional connectivity (FC) (1), which measures the temporal correlation of spontaneous hemodynamic signals (HemoS), is widely accepted as a core noninvasive tool to infer the functional network organization of brains in humans and other animals (2–6). Recent studies further suggest that HemoS-based FC (Hemo-FC) is sensitive enough to detect network-level functional changes due to behavioral training (7), wakefulness levels (8), and psychiatric diseases (9–12). It is commonly assumed that spatial organization of Hemo-FC and its state-dependent changes reflect large-scale spatiotemporal dynamics of spontaneous neuronal activity that is converted into HemoS (13). However, previous studies supporting the link between neuronal activity and Hemo-FC were limited to observations from small numbers of selected brain areas (14–20). Moreover, in most studies, neuronal activity and HemoS were recorded in separate experimental sessions (14, 15, 18, 19). Thus, direct evidence linking large-scale dynamics of spontaneous neuronal activity and Hemo-FC is still lacking.

To date, optical imaging and electrophysiological studies in animals have reported multiple heterogeneous dynamics of large-scale spontaneous neuronal activity (16, 21–28). Waves of activity that propagate across the cortical network are commonly observed across different experimental setups (16, 21–26). Recent fMRI studies by Mitra and coworkers (29–31) revealed that such large-scale propagation structure of spontaneous activity indeed has spatial information leading to Hemo-FC. Studies using voltage-sensitive dye imaging reported more complex dynamics, such as spiral waves confined within a cortical area (27) and transient neuronal coactivations among a subset of anatomically connected cortical areas (28). In relation to Hemo-FC, the latter type of activity, transient neuronal coactivations, is particularly interesting. Given the close correspondence between anatomical connectivity and Hemo-FC (32), it is tempting to speculate that such neuronal coactivations are converted into spatially similar coactivations in HemoS (33) that in turn produce spatial patterns of Hemo-FC.

However, several gaps must be bridged before establishing a connection between large-scale dynamics of neuronal activity and Hemo-FC. In particular, it is important to clarify the relationship between two types of spontaneous neuronal activity—namely, the global waves (16, 21–26) and the transient coactivations (28). One possibility is that the transient coactivations are caused by brief synchronization and desynchronization of neuronal activity in subsets of brain areas (34) and thus are distinct from the global waves. If this possibility were true, how are the transient coactivations and the global waves intermingled within the resting state? Do they both contribute to Hemo-FC? If so, what is the spatial component of Hemo-FC that reflects each of them? Another possibility is that the neuronal coactivations are embedded within the dynamics of global waves. In this case the global waves and the neuronal coactivations are different descriptions of the same type of event. If this latter possibility were true, how can spatially specific patterns of Hemo-FC emerge from the global waves that propagate across the entire neocortex? Can low-frequency HemoS (35) extract precise spatial patterns of transient neuronal coactivations embedded within the global waves? To answer these questions, one needs to observe large-scale spatiotemporal dynamics of spontaneous neuronal activity simultaneously with HemoS arising from them.

In the present study, we devised simultaneous wide-field imaging of calcium and intrinsic optical signals (36) that allowed us to monitor calcium signals (CaS) that reflect neuronal spiking activities (37) and HemoS at high spatiotemporal resolution in the entire dorsal neocortex of transgenic mice expressing a genetically encoded calcium indicator (38). Using lightly anesthetized mice, we found that transient neuronal coactivations occurred in subsets of cortical areas sharing high FC. Such neuronal coactivations were often embedded within the global waves of spontaneous neuronal activity that frequently propagated across the entire neocortex. Furthermore, we found that such neuronal coactivations were indeed followed by spatially similar coactivations in HemoS with a hemodynamic delay of a few seconds. Finally, we confirmed that the presence of the neuronal coactivations was necessary for setting the spatial structure of Hemo-FC.

Results

Spontaneous HemoS Correlated with Simultaneously Recorded CaS with a Hemodynamic Delay.

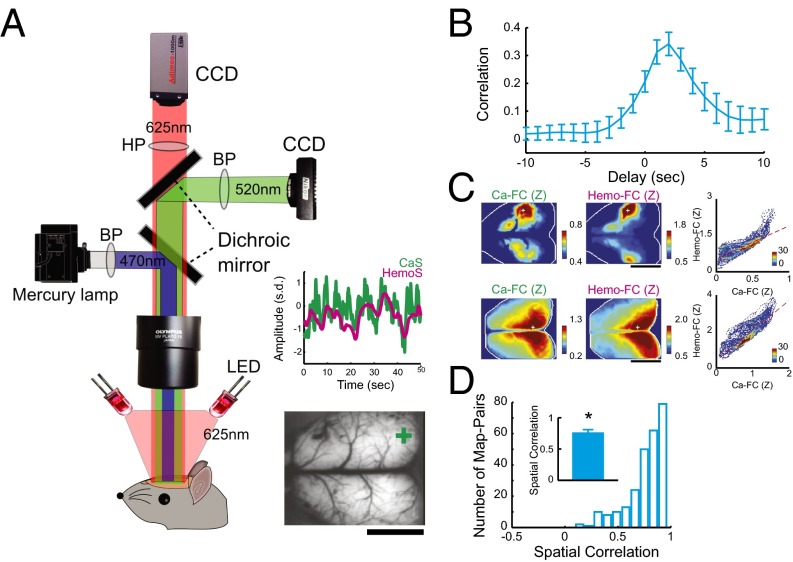

Transgenic mice expressing GCaMP3 in neocortical excitatory neurons (38) were used to simultaneously image CaS and HemoS from almost the entire neocortex (Fig. 1A). Because an increase in neuronal activity was expected to cause a decrease in HemoS measured at 625 nm (36), we inverted HemoS in the following analyses. Continuous imaging of the resting brain revealed complex dynamics of spontaneous neuronal activity consisting of various, mostly left–right symmetric spatial patterns in CaS as well as in HemoS, with CaS showing faster dynamics than those of HemoS (Movie S1). To examine the relationship between simultaneously recorded CaS and HemoS, we first compared the time courses of CaS and HemoS averaged in a small region of interest (ROI) defined by anatomical positions (Fig. S1A). As expected from the presence of hemodynamic delay, CaS and HemoS measured in the same ROIs exhibited similar time courses with HemoS lagging behind CaS by a few seconds (Fig. 1A, Inset). Cross-correlation analysis confirmed that, on average, spontaneous HemoS lagged behind CaS by ∼2 s (2.0 ± 0.22 s, mean ± SEM; Fig. 1B). A hemodynamic delay of ∼2 s was also observed in control experiments (Fig. S1 B and C). In addition to the hemodynamic delay, a high-frequency component of CaS also appeared attenuated in HemoS most likely due to the low-pass filtering effect of the hemodynamic response function or to the insensitivity of HemoS to high-frequency neural activity (39–41) (Fig. S1D; only high-pass filter at 0.01 Hz was used both for CaS and HemoS). These results confirmed that our simultaneous imaging setup allowed us to monitor large-scale spatiotemporal neuronal activity as well as HemoS originating from them.

Fig. 1.

Simultaneous imaging of CaS and HemoS revealed hemodynamic delay and spatial similarity of Ca-FC and Hemo-FC. (A) Experimental setup. (Inset) Example time courses of simultaneously recorded CaS and HemoS in a ROI indicated by a green cross in the field of view. (B) Cross-correlation between CaS and HemoS. Mean across mice (n = 7). (C) Representative maps of Ca-FC and Hemo-FC and scatterplots comparing Ca-FC and Hemo-FC pixel by pixel. Maps were spatially smoothed by a Gaussian filter (σ = 78 μm) to enhance contrast. (Upper) S1-barrel seed. (Lower) Retroplenial seed. Scatterplots are shown as density plots to enhance visibility. (D) Distribution of spatial correlation between Ca-FC and Hemo-FC (n = 259 pairs). (Inset) Mean spatial correlation within each mouse (n = 7). *P < 10−6 (t test, n = 7 mice). Error bars, SEM. (Scale bars, 5 mm.)

Fig. S1.

Comparison of CaS and HemoS across anatomical ROIs. (A) Anatomically defined ROI. (B) Time course of HemoS triggered by spontaneous CaS transients (mean across mice, n = 7). Time 0 was the peak of the CaS transient (see SI Materials and Methods for definition). Error bar, SEM. (C) CaS and HemoS evoked by visual stimulation. Green and magenta traces show the time courses of simultaneously recorded CaS and HemoS, respectively. Time 0 is the onset of visual stimulation. The horizontal black bar indicates the duration of the stimulus (4 s). Solid lines, mean across animals (n = 2 mice). Dotted lines, individual mice. (D) Comparison of CaS, HemoS, and CaS convolved with hemodynamic response function (HRF). Note that only high-pass filter at 0.01 Hz was applied to CaS (green) and HemoS (magenta). (Inset) A gamma function mimicking HRF that best fitted CaS to HemoS. Blue trace shows the CaS convolved with HRF. (E) Maps of Ca-FC for 35 ROIs in an example animal. Positions of ROIs are indicated by green squares. Color range clipped between mean −2 SD and mean +2 SD of Ca-FC for each map. Corresponding values of Ca-FC(Z) for all of the maps are: (Left) M1 [−1.3 1.3]; M2 [−0.9 0.9]; mPar [−1.1 1.2]; lPar [−1.1 1.2]; pPar [−0.9 1]; Rsp [−0.8 0.9]; V1 [−1 1]; mV2 [−1.2 1.3]; lV2 [−0.9 0.9]; AC [−0.4 0.4]; FAsc [−1.2 1.1]; Tr-S1 [−0.7 0.8]; HL-S1 [−0.8 0.9]; Sh-S1 [−0.7 0.8]; FL-S1 [−1.2 1.1]; B-S1 [−0.7 0.7]; H-S1 [−1.2 1.1]; TA [−0.6 0.6]. (Right) M1 [−1.3 1.2]; M2 [−0.8 0.8]; mPar [−1.1 1.2]; lPar [−1.1 1.2]; pPar [−1.1 1.2]; Rsp [−0.9 1.0]; V1 [−1.2 1.3]; mV2 [−1.3 1.4]; lV2 [−1.1 1.1]; AC [−0.4 0.4]; FAsc [−1.3 1.2]; Tr-S1 [−0.8 0.9]; HL-S1 [−0.8 0.8]; Sh-S1 [−0.7 0.8]; FL-S1 [−1.1 1]; B-S1 [−0.7 0.7]; H-S1 [−1 0.9]. GSR was performed to enhance contrast. (F) Maps of Hemo-FC for the same 35 ROIs in the same animal. Color range clipped between mean −2 SD and mean +2 SD of Ca-FC for each map. Corresponding values of Hemo-FC(Z) for all of the maps are: (Left) M1 [−4.6 4.4]; M2 [−3.2 3.5]; mPar [−3.9 4.5]; lPar [−3.8 4.4]; pPar [−3.1 4]; Rsp [−4 4.3]; V1 [−3.7 4.1]; mV2 [−4.3 4.8]; lV2 [−2.7 3.5]; AC [−4.6 4.4]; FAsc [−2.6 3.6]; Tr-S1 [−2.6 3.5]; HL-S1 [−2.5 3.5]; Sh-S1 [−2.5 3.5]; FL-S1 [−3.7 3.7]; B-S1 [−2.1 2.7]; H-S1 [−4.4 4.1]; TA [−3.1 3.5]. (Right) M1 [−4.4 4.3]; M2 [−2.8 3.4]; mPar [−3.8 4.5]; lPar [−3.5 4.3]; pPar [−3 3.9]; Rsp [−3.9 4.2]; V1 [−3.5 4.1]; mV2 [−4.3 4.8]; lV2 [−2.5 3.3]; AC [−2.1 2.5]; FAsc [−4.7 4.4]; Tr-S1 [−2.5 3.4]; HL-S1 [−2.4 3.3]; Sh-S1 [−2.4 3.4]; FL-S1 [−3.6 3.7]; B-S1 [−2.2 2.7]; H-S1 [−4.3 4.1]. GSR was performed to enhance contrast. (G) Lagged temporal correlation of the time courses of homotopic ROIs in the two hemispheres. Lagged temporal correlation for all of the pairs of homotopic ROIs were averaged to obtain a lagged temporal correlation for each animal. Thick traces show lagged temporal correlation across seven mice. Thin lines show ± SEM across seven mice. For both calcium and hemodynamic signals, the lagged temporal correlation peaked at the zero lag, indicating that spontaneous calcium and hemodynamic signals had bilateral symmetry.

Spatial Maps of FC Were Similar for CaS and HemoS.

To examine the overall correspondence between the spatial structure of spontaneous neuronal activity and HemoS, we compared the spatial patterns of CaS-based FC (Ca-FC) and Hemo-FC across the whole brain. Spatial maps of Ca-FC and Hemo-FC that were obtained using the same seed location appeared very similar (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1 E and F; see also Fig. S2 B and D for ROI-wise FC matrices). For both Ca-FC and Hemo-FC, we observed characteristic features of the resting-state FC, such as a mirror symmetric pattern across hemispheres (42) and strong FC between functionally related regions [e.g., primary motor cortex (M1) and primary somatosensory cortex (S1) (20, 43)] (Fig. S1G). The spatial correlation between Ca-FC and Hemo-FC was consistently positive across different seed locations (0.75 ± 0.22, mean ± SD, n = 259; P < 10−175, t test; Fig. 1D) and across animals (0.75 ± 0.08, mean ± SD, n = 7; P < 10−6, t test; Fig. 1D, Inset). These results corroborate the notion that Hemo-FC reflects underlying neuronal activity (15, 18, 19).

Fig. S2.

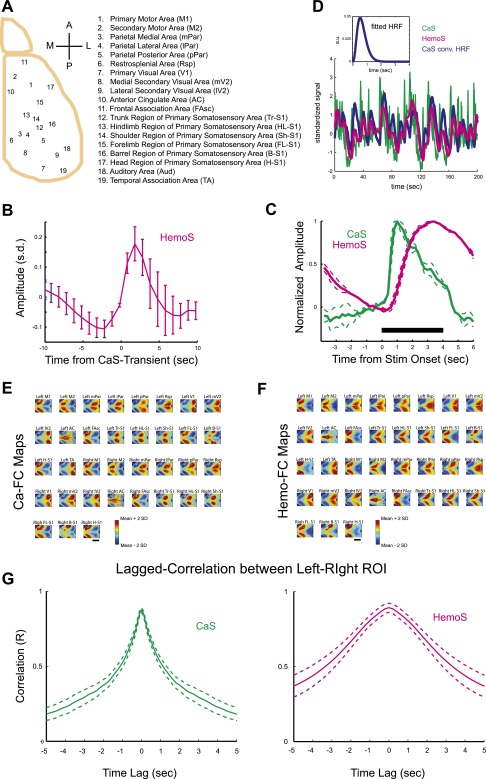

Time-delay analysis a la Mitra et al. (29, 30). TD for CaS and HemoS in a representative animal. (A1) Example plots of cross-covariance between ROI 1 and ROI 8. Sampling rate for CaS and HemoS were 5 and 10 Hz, respectively. See Fig. S1A for ROI abbreviations. (A2) Representative scatterplot showing the correspondence between TD in CaS and HemoS for one animal. Each dot indicates a unique pair of ROIs. Correlation coefficient was 0.53 for this animal (R = 0.31 ± 0.05, mean ± SEM, n = 7. P < 0.002, t test). Red dotted line shows a regression line. (A3) Scatterplot showing the correspondence between the absolute value of TD in CaS as shown in A2 and Ca-FC. Red dotted line shows a regression line. Correlation coefficient was −0.65 for this animal (R = −0.41 ± 0.06, mean ± SEM, n = 7. P < 0.0001, t test). (A4) Same as A3 but for HemoS. Correlation coefficient was −0.85 for this animal (R = 0.64 ± 0.05, mean ± SEM, n = 7. P < 0.0001, t test). (B) ROI-based FC matrix for CaS. Mean across seven mice. (C) ROI-wise correlation of TD profiles in CaS. For each pair of ROIs, TD profiles averaged across animals were used to calculate the correlation. Correlation coefficient between the off-diagonal and unique values in the matrices shown in B and C was 0.62 (P < 0.0001). (D) ROI-based FC matrix for HemoS. Mean across seven mice. (E) ROI-wise correlation of TD profiles in HemoS. Correlation coefficient between the off-diagonal and unique values in the matrices shown in D and E was 0.63 (P < 0.0001).

Spontaneous Waves of CaS Frequently Propagated Across the Whole Brain.

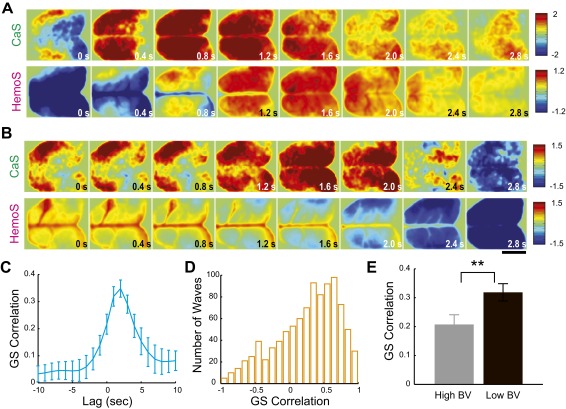

The goal of the present study is to understand how large-scale dynamics of neuronal activity is reflected in the spatial structure of Hemo-FC. To this end, we next examined large-scale spatiotemporal dynamics of CaS and HemoS. When we visually inspected movies of spontaneous CaS, we immediately noticed the frequent occurrence of waves of activity that propagated across almost all of the imaged cortical regions (Fig. 2A, Fig. S3A, and Movie S2) (16, 21–26). We found that such global brain activity (GBA) identified in CaS was mostly followed by brain-wide activity in simultaneously recorded HemoS with a delay of a few seconds (Fig. S3A). [We note that, in some cases, when strong HemoS was present in large blood vessels, clear divergence between CaS and HemoS during GBA was observed (Fig. S3B; see SI Text for details)]. To quantify the relationship between CaS and HemoS during GBA, we detected epochs corresponding to GBA using the time course of the proportion of active pixels in the brain (Fig. 2B). For each GBA, we then computed the global signal (GS), which is a signal averaged across all pixels in the cortex. A cross-correlation between GS in CaS and HemoS showed a maximum positive correlation with a time lag of ∼2 s (Fig. S3C), suggesting that Hemo-GS significantly reflected neuronal activity during GBA (16).

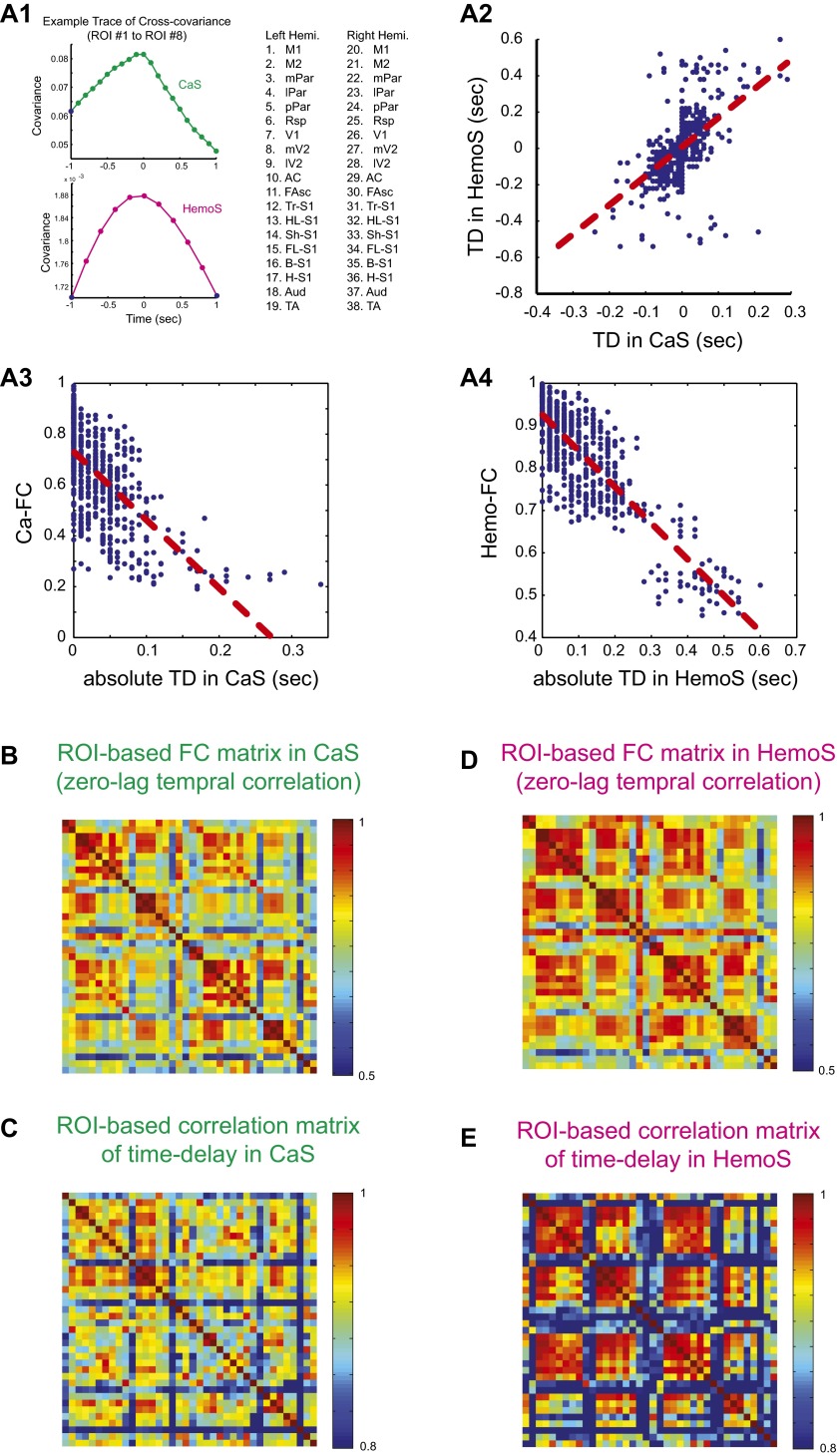

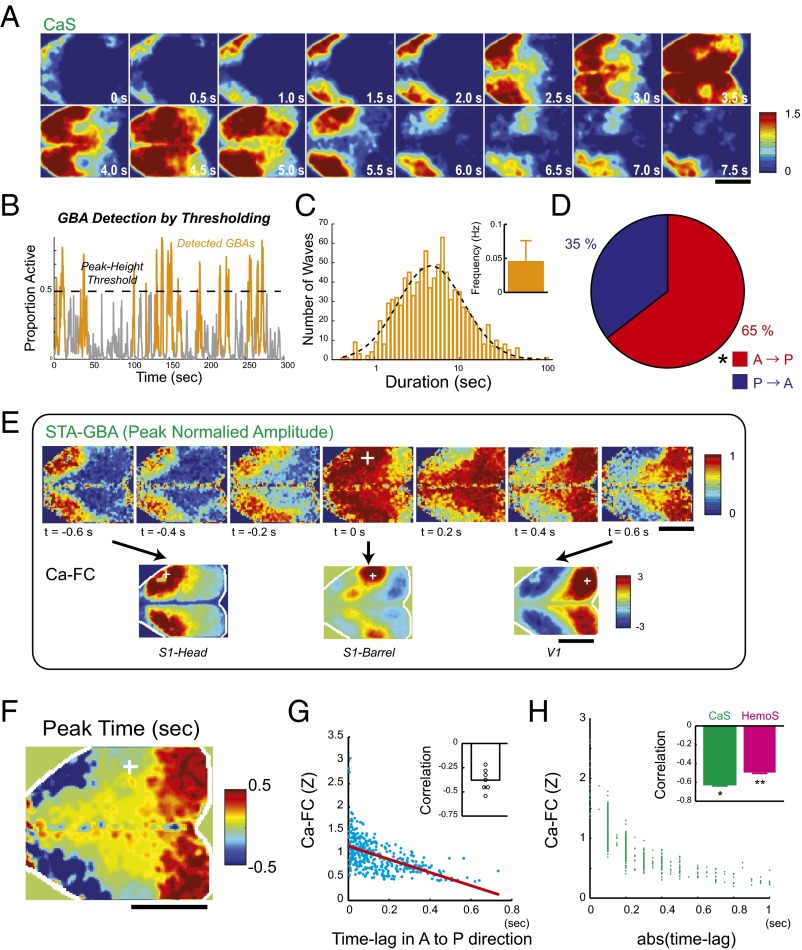

Fig. 2.

Phase of GBA-encoded spatial information of FC. (A) A representative GBA in CaS. (B) Schematics of GBA detection. Time course of proportion of active pixels within the brain (gray) was used to detect waves of activity whose peak exceeded threshold (orange). (C) Distribution of GBA duration (n = 958). Dotted line, Gaussian fit on a log scale. (Inset) Mean frequency of GBA (n = 71 scans). (D) Pie chart showing fraction of anterior-to-posterior (A→P) and posterior-to-anterior (P→A) GBA. Distribution of GBA was significantly different from random (50:50) distribution. n = 958 GBA in seven animals. +, P < 10−9, χ2 test (50:50 as null hypothesis) (22). (E) A representative STA movie in AP-GBA. Amplitude in each pixel is normalized to have peak and minimum values of 1 and 0, respectively. (Lower) Maps of Ca-FC for different seed positions (Left, S1-head; Center, S1-barrel; Right, V1). White cross, seed location (S1-barrel). (F) A map of peak times for the STA movie shown in E. (G) Scatterplot of mean time lag (in the anteroposterior direction) and Ca-FC. (Inset) Correlation between the time lag and Ca-FC in all animals (n = 7). (H) Scatterplot showing the relationship between the median value of the abs(time lag) and Ca-FC for each pair of ROIs. (Inset) Correlation between the median abs(time lag) and FC for CaS and HemoS (ROI based). Mean across mice (n = 7). Error bars, SEM. *P < 5 × 10−6. **P < 3 × 10−6 (t test, n = 7). (Scale bars, 5 mm.)

Fig. S3.

Spontaneous global brain activity detected by CaS and HemoS. (A) A representative GBA simultaneously recorded in CaS and HemoS. (B) Example of clear dissociation in CaS and HemoS. In this example, GBA was visible only in CaS. Note the large vascular activity in HemoS. (C) Cross-correlation between Ca-GS and Hemo-GS. Mean across mice (n = 7). (D) Distribution of the correlations between Ca-GS and Hemo-GS in all GBA across seven mice (n = 954). (E) Comparison of the correlations between Ca-GS and Hemo-GS in GBA with low and high BV signal (black and gray, respectively). Dotted lines indicate the mean of each distribution. Consistent with the example shown in B, Ca-GS and Hemo-GS tended to dissociate during periods with high BV signal. **P < 0.021 (rank-sum test, n = 191 for both low and high BV signal GBA). (Scale bars, 5 mm.)

GBA Showed Characteristic Pattern of Activity Propagation.

The duration of GBA was ∼5 s with its distribution well fit by a log-normal distribution (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the frequency of GBA was 0.045 ± 0.031 Hz (mean ± SD, n = 71 scans; Fig. 2C, Inset), which falls inside a frequency range considered to be most relevant for resting-state FC in fMRI (0.01–0.1 Hz) (44, 45). We thus further examined the spatiotemporal dynamics of GBA and searched for a potential link with FC.

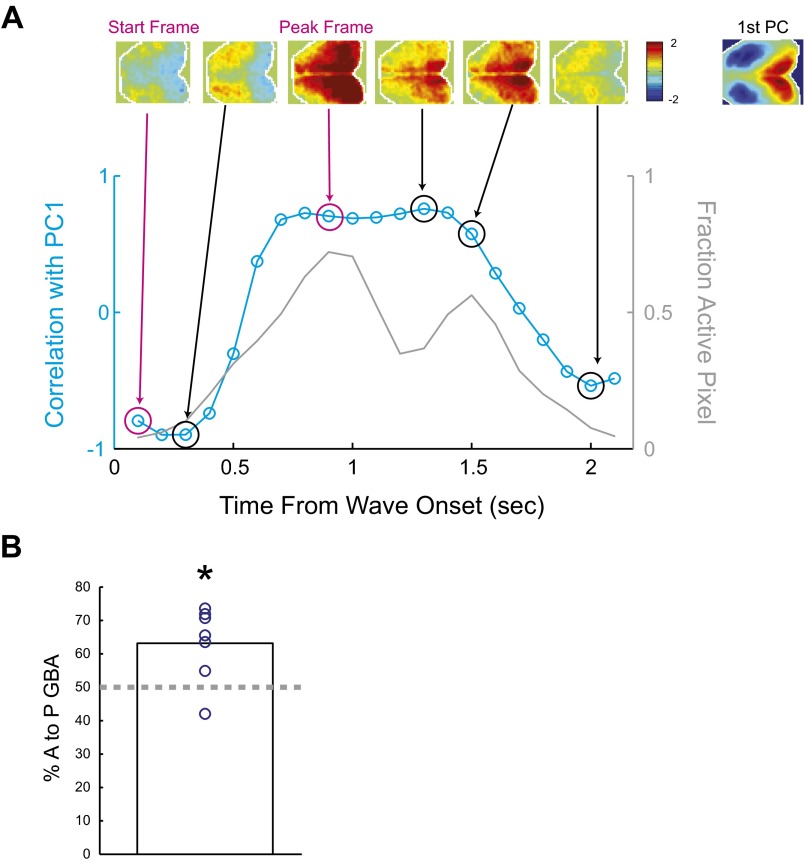

In many cases, GBA originated from the anterior part of the neocortex and then propagated posteriorly (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3A). Overall, we found a moderate but significant bias toward anterior-to-posterior propagation of GBA (Fig. 2D and Fig. S4). The presence of such bias in the propagation of spontaneous neuronal activity is consistent with a recent imaging study in mice (22) and resembles activity propagation during the slow wave sleep in humans (23). We focused on a subset of GBA showing prominent anterior-to-posterior propagation (AP-GBA) [37% of GBA classified as AP-GBA for the representative animal and 38 ± 4.9% for all animals (mean ± SEM, n = 7)]. To visualize the average pattern of activity propagation during AP-GBA, we constructed spike-triggered average (STA) movies using spike-like transients in the time course of CaS (22) (Fig. S5A). Fig. 2E shows the example STA movie with the seed placed at right S1. Notably, the STA movie revealed that different sets of cortical areas were activated at different phases of AP-GBA: (i) The anterior regions were first activated at around –0.6 to –0.2 s. (ii) Then, the middle regions including S1 were activated at around –0.2 to 0.2 s. (iii) Finally, the posterior regions including V1 were activated at around 0.2 to 0.6 s The spatial map of the peak time in each pixel further revealed sequential activation of cortical areas (Fig. 2F).

Fig. S4.

Anterior-to-posterior propagation of GBA. (A) Example GBA and analysis procedure. Gray trace shows time course of the proportion of active pixels within the brain during example GBA. Color-scaled activity maps above the trace show activity in the frames indicated by arrows. Magenta arrows indicate frames at the start and the peak of the time course of the proportion of active pixels within the brain. To analyze propagation of GBA, we first temporally down-sampled CaS by a factor of five and concatenated all of the frames across all GBA in all animals. Images in different animals were coregistered to a common template. We then performed principal component analysis (PCA) on the concatenated data. The first principal component (indicated as first PC in the figure) showed a prominent anterior-to-posterior gradient of activity. We then computed the spatial correlation between the first PC and each frame in GBA. The cyan trace in the figure shows the time course of the correlation with the first PC for the example GBA. In this example, the correlation at the start frame was negative, indicating activity stronger in the anterior than posterior part. At the peak frame, the correlation was positive, indicating activity stronger in the posterior than anterior part. As an index to quantify anterior–posterior flow of GBA, we calculated the difference between the values of the correlation with the first PC in the peak frame and the start frame for each GBA. Activity flow was designated as anterior to posterior if the index was positive, and posterior to anterior if the index was negative. (B) Proportion of GBA propagating in anterior-to-posterior directions across animals. Anterior-to-posterior propagation in GBA was significantly more frequent across animals (6/7 animal). *P < 0.047, signed-rank test, n = 7.

Fig. S5.

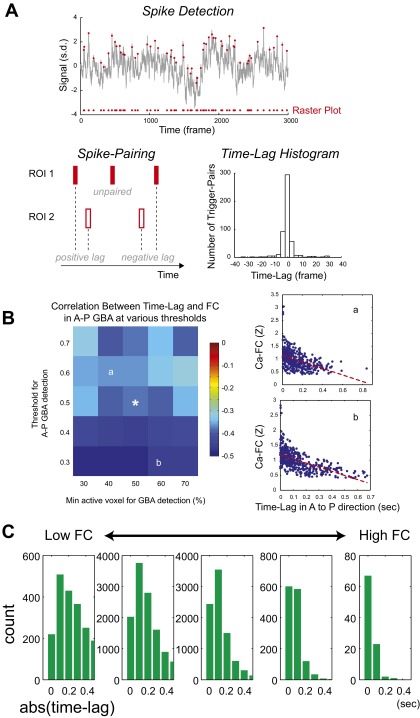

Analysis of time lag of spontaneous activity across ROI pairs. (A) Schematics for detecting CaS transients (see SI Materials and Methods for details). (Upper) For each ROI, a raster plot was constructed from each time course of the CaS (gray trace) by detecting Ca transients (red dots). An example ROI was placed in the retrosplenial cortex. Note that the time course before high-pass filtering is shown. (Lower Left) Raster plots in two ROIs were compared to find pairs of Ca transients occurring in close temporal proximity. Then, the time lag was calculated for each pair of Ca transients. (Lower Right) Example histogram of the time lag for a pair of ROIs (retrosplenial cortex and S1-hindlimb). (B) Robustness of the relation between time lags during AP-GBA and FC against the choice of thresholds. Correlation between time lags during AP-GBA and FC (Fig. 2G) were examined with different thresholds for (i) the minimum percent active pixels in the brain for GBA and (ii) the bias index for the anterior-to-posterior flow. The colored matrix (Left) shows mean correlation between time lags during AP-GBA and FC across seven mice for different combinations of the two thresholds. Original thresholds used in Fig. 2G are 50% and 0.5%, respectively, for the minimum percent active pixels and the bias index. White asterisk indicates the original choice of threshold used in Fig. 2G. Scatterplots show examples from one animal taken from the threshold values indicated by a and b. (C) Representative histograms of the abs(time lag) for different levels of Ca-FC. Pairs of ROIs are binned to five groups by the strength of the Ca-FC. Same data as used in Fig. 2E. Note that median value of the abs(time lag) decreased as Ca-FC between the pair increased, indicating FC arising from activity propagation (see also Fig. S6 and SI Discussion, Model-Based Analysis of Propagating and Nonpropagating Spontaneous Activity).

Transient Coactivations Resembling FC Maps Were Embedded in GBA.

Interestingly, spatial maps of cortical areas sharing similar peak time resembled maps of Ca-FC with various seed locations (Fig. 2 E and F), suggesting that each map of Ca-FC corresponds to a particular phase of AP-GBA. Comparison of Ca-FC and the time lag of CaS transients in the time courses across pairs of ROIs showed a significant negative correlation (R = –0.53, P < 0.001; Fig. 2G) that were consistent across all animals (P < 10−4, t test; Fig. 2G, Inset), confirming that areas that had similar peak times shared high Ca-FC. The result was also significant with partial correlation analysis that controlled for the effect of the distance between the pairs of ROIs (P < 0.0062, t test) and robust against change of thresholds used in the analysis (Fig. S5B). To see whether this relationship between the time lag and FC is specific to AP-GBA or is general phenomena in the data, we next analyzed the relationship between time lag and FC using all of the data. To avoid cancelation between activity propagation going in different directions, we used absolute values of the time lag (Fig. S5C; SI Materials and Methods). The negative correlations between Ca-FC, as well as Hemo-FC, and the median of the absolute values of the time lag across ROI pairs were also seen for data across all time periods (Fig. 2H and Fig. S6). Comparison with simulations suggested that such negative correlations indicate FC arising from propagating activity rather than that arising from nonpropagating flash-like coactivations (34) (see Fig. S6 and SI Text for details).

Fig. S6.

Relationship between time lag of activity propagation and FC. (A–C) Simulated spontaneous activity with and without propagation. See SI Text for details of the simulation. (A) ROIs used for visualization of simulated spontaneous activity. See Movies S3 and S4 for examples of spontaneous activity with and without propagation. (B, Left) Example of simulated activity without propagation (Movie S3). (Right) FC between pixels for the simulated scan. (C, Left) Example of simulated activity with propagation (Movie S4). (Right) FC between pixels for the simulated scan. The correlation between FC shown in B and C was >0.99. (D–K) Histograms of the abs(time lag) for different levels of FC and scatterplots showing relationship between the median value of the abs(time lag) and FC for simulations and for experimental data. (D) Representative histograms for a simulated scan without propagation. Pairs of pixels were binned to five groups by the strength of FC. (E) Scatterplot for the same simulated scan as in D. (F) Representative histograms for a simulated scan with propagation. Same convention as in D. (G) Scatterplot for the same scan as in F. (H) Representative histograms for an example CaS scan. Pairs of ROIs were binned to five groups by the strength of Ca-FC. (I) Scatterplot for the same scan as in H. (J) Representative histograms for a representative HemoS scan (simultaneously recorded with the CaS scan shown in H and I). Pairs of ROIs were binned to five groups by the strength of the FC. (K) Scatterplot for the same scan as in J. (L) Distribution of the correlation between the median of the abs(time lag) and FC between pairs. Blue trace, distribution for simulation without propagation (n = 1,000). Black trace, distribution for simulation with propagation (n = 1,000). Dotted lines, means of the distributions. Green lines, mean (long) and individual (short) correlation values for CaS (n = 7). Magenta lines, mean (long) and individual (short) correlation values for HemoS (n = 7).

Furthermore, we found consistent relationship between activity propagation and FC, in CaS and HemoS, using analysis recently developed by Mitra and coworkers (29–31) (Fig. S2 and SI Text).

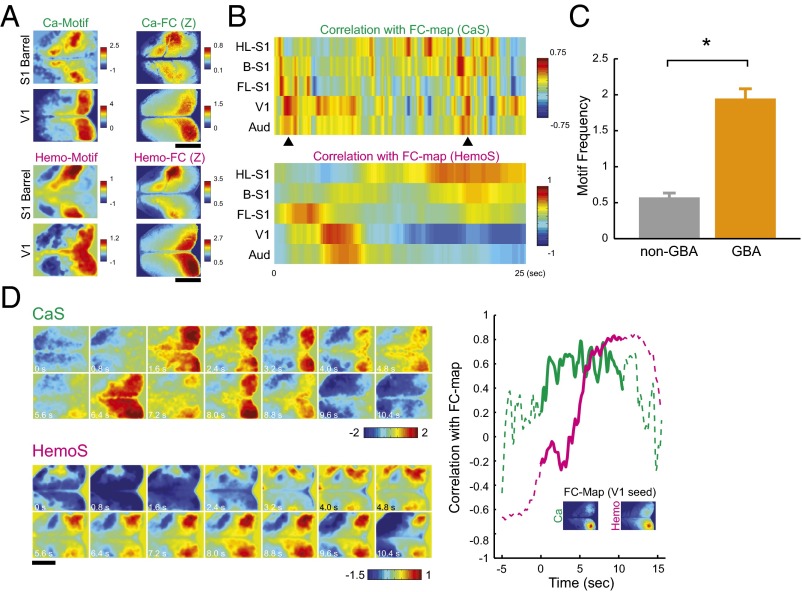

Observed similarity between the maps of Ca-FC and different phases of AP-GBA motivated us to compare frame-to-frame activity patterns of CaS with the maps of Ca-FC. Consistent with a recent VSD imaging study (28), we frequently observed snapshots of coactivations of distant brain areas closely resembling the maps of Ca-FC (Fig. 3A, Upper). Coactivations resembling different maps of Ca-FC often occurred in sequences (Fig. 3B, Upper, arrowheads). To quantify coactivations in CaS, we adopted the analysis developed in the previous VSD study (28): We first calculated the time course of the correlation between the activity pattern in each frame and the FC maps of selected seeds (Fig. 3B). We then defined image frames whose spatial correlation with FC maps exceeded a threshold value as “Ca motifs”. We found that Ca motifs occurred more often during GBA than non-GBA periods (P < 0.0006, paired t test; Fig. 3C). These results suggest that the phase of GBA encoded spatial maps of FC.

Fig. 3.

Coactivations resembling FC maps appeared spontaneously in CaS and HemoS. (A) Examples of single frames in CaS and HemoS that resembled maps of Ca-FC and Hemo-FC, respectively. (B) Example time courses of the correlation between the activity pattern in each frame and FC maps (Upper, CaS; Lower, HemoS). FL-S1, forelimb area of S1. HL-S1, hindlimb area of S1. B-S1, barrel area of S1. Aud, auditory cortex. (C) Frequency of Ca motifs with and without GBA. Mean across mice (n = 7). Error bars, SEM. *P < 0.0006 (paired t test, n = 7 mice). (D) Example movie showing coactivations in CaS and HemoS. (Right) Time courses of correlation between activity pattern and FC map (seed, V1). Solid lines correspond to the time window shown as movies (0–10.4 s). (Scale bars, 5 mm.)

Simultaneous Imaging Revealed Significant Coupling Between Coactivations in CaS and HemoS.

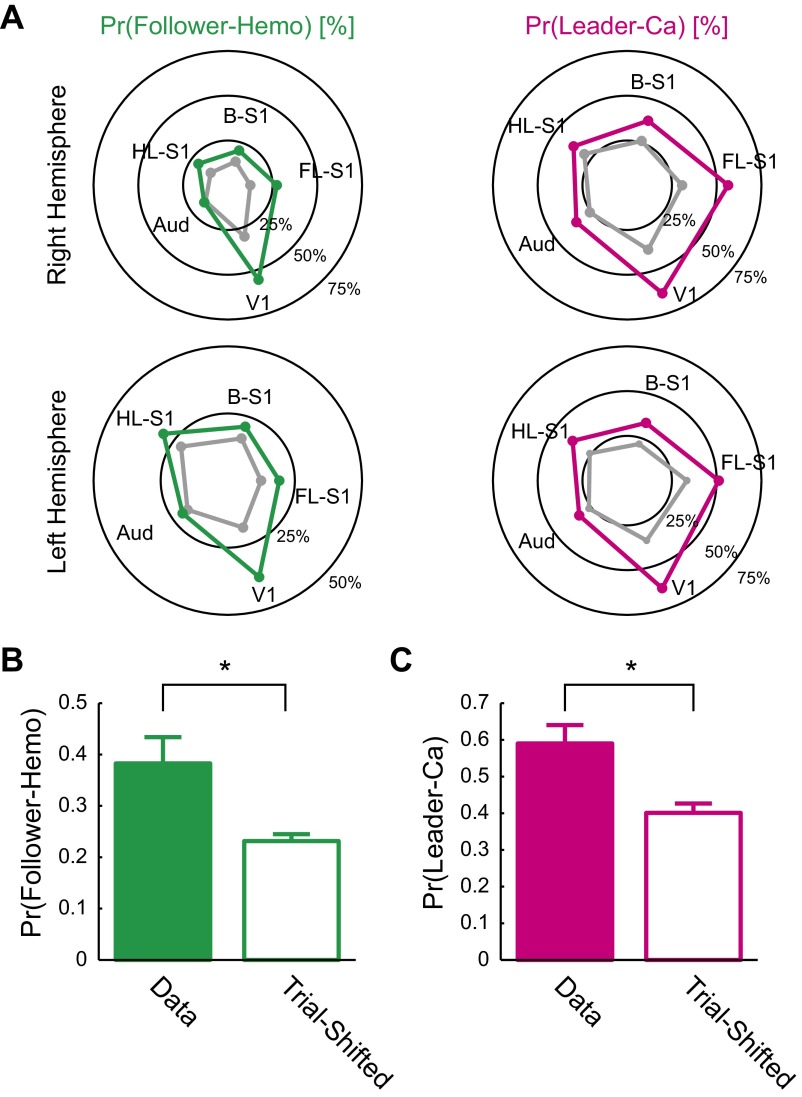

In HemoS, we also found transient coactivations that closely resembled spatial patterns of Hemo-FC (Fig. 3A, Lower) (33, 46). In accord with the notion that neuronal coactivation caused coactivation in HemoS, we frequently found transient coactivations in CaS preceding spatially similar coactivations in HemoS with a delay of ∼2 s (Fig. 3D). To quantitatively examine the relationship between coactivations in CaS and HemoS, we defined Hemo motifs using the same procedure used to define Ca motifs. We then calculated the probability of a Ca motif being followed by a Hemo motif of the same seed (follower-Hemo motif; Fig. 4A, Upper) as well as the probability of a Hemo motif being preceded by a Ca motif of the same seed (leader-Ca motif; Fig. 4A, Lower). For all seeds, the probability of finding the follower Hemo motif [Pr(follower Hemo)] as well as the probability of finding the leader Ca motif [Pr(leader Ca)] was larger than that of trial-shifted controls (Fig. S7A). Pr(follower Hemo) and Pr(leader Ca) for all motifs across seeds were 30 ± 6.2% and 47 ± 7.9% (mean ± SEM, n = 7 mice), respectively. When the motifs of the left and right hemisphere seeds were merged to account for a high correlation of spontaneous activity in the left and right hemispheres, the detection probability increased to 38 ± 5.1% and 59 ± 5.0%, respectively for Pr(follower Hemo) and Pr(leader Ca) (mean ± SEM, n = 7 mice). Both Pr(follower Hemo) and Pr(leader Ca) were significantly higher than their trial-shifted controls (P < 0.016 for both, paired t test, n = 7 mice; Fig. S7 B and C). These results suggest that coactivations in CaS caused spatially similar coactivations in HemoS.

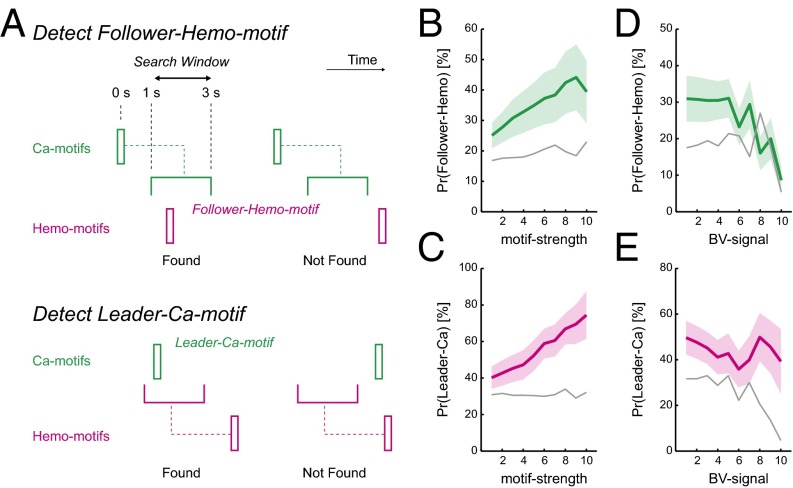

Fig. 4.

Coactivations in CaS preceded spatially similar coactivations in HemoS. (A) Schematics of procedure for detecting follower-Hemo motifs (Upper) and leader-Ca motifs (Lower). (Upper) For each Ca motif of a seed location, presence or absence of a Hemo motif in the search window (1–3 s after the Ca motif) was examined. (Lower) Same procedure was done for Hemo motifs, searching for Ca motifs in the search window (1–3 s before the Hemo motif). (B) Pr(follower Hemo) as a function of motif strength. Mean across mice (n = 7). Shaded regions indicate SEM. Gray lines indicate the mean of the trial-shifted control. (C–E) Same convention as B but for Pr(leader Ca) as a function of motif strength (C), Pr(follower Hemo) as a function of BV signal (D), and Pr(leader Ca) as a function of BV signal (E).

Fig. S7.

Ca motifs preceded Hemo motifs. (A) Polar plots showing the probability of detecting follower-Hemo motifs or leader-Ca motifs for each seed in each hemisphere. Green and magenta lines indicate the mean probability of detecting follower-Hemo motifs and leader-Ca motifs across seven mice, respectively. Gray lines indicate trial-shifted control. See Fig. S1A for abbreviations. (B) Pr(follower Hemo) for the data (Left) and trial-shifted control (Right). Mean across mice (n = 7). Error bar, SEM. (C) Pr(leader Ca) for the data (Left) and trial-shifted control (Right). Mean across mice (n = 7). Error bar, SEM. *P < 0.016 (paired t test).

Factors Modulating the Coupling Between the Coactivations in CaS and HemoS.

Because the coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs was less than 100%, we searched for factors that might modulate the coupling between them. We hypothesized that Ca motifs that were spatially more similar to FC maps (i.e., less neuronal noise added to the motif-type activity) were more likely to be converted into follower Hemo motifs compared with Ca motifs that were noisy and dissimilar to FC maps. To test this hypothesis, for each motif frame, we defined the motif strength as the spatial correlation between activity patterns in the motif frame and the FC map of the selected seed. As expected, the motif strength of Ca motifs positively correlated with Pr(follower Hemo) (R = 0.25, P < 0.033; Fig. 4B). Similarly, the motif strength of Hemo motifs positively correlated with Pr(leader Ca) (R = 0.44, P < 0.0002; Fig. 4C). Thus, the coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs were modulated by the motif strength.

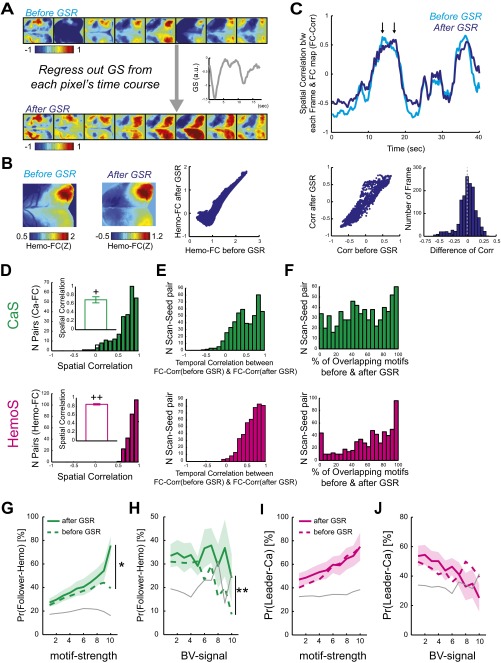

Next, based on the observation that CaS and HemoS decoupled in the presence of large nonneuronal noise (Fig. S3 B and E), we examined the effect of nonneuronal noise on the coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs. The strength of nonneuronal noise was quantified by averaging HemoS in the blood vessels (BV signal). We found that Pr(follower Hemo) was negatively correlated with BV signals at the time of motif frame (R = –0.38, P < 0.001; Fig. 4D), suggesting that Ca motifs were less likely to be converted into Hemo motifs in the presence of large nonneuronal noise. However, Pr(leader Ca) did not show a significant correlation with BV signals (R = –0.064, P > 0.59; Fig. 4E). Use of the global signal regression (GSR), a commonly used method for removing nonneuronal noise in HemoS (47), significantly improved the coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs (Fig. S8 and SI Text). Notably, after GSR, Pr(follower Hemo) approached 75.6% for Ca motifs with the highest level of motif strength (Fig. S8G). Taken together, these results suggest that in most cases, strong coactivations in CaS are converted into spatially similar HemoS. In other cases, the conversion failed due to the presence of strong nonneuronal noise in HemoS.

Fig. S8.

Coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs improved after GSR. (A–C) Effect of GSR. (A) Example HemoS and maps of Hemo-FC before and after GSR. From the time course of each pixel (Top), GS (Middle) was regressed out to obtain the time course after GSR (Bottom). (B) Maps of Hemo-FC before and after GSR. Spatial maps of Hemo-FC before (Left) and after (Center) GSR appeared similar. (C, Upper) Time courses of the correlation between the activity pattern in each frame of CaS and the maps of Ca-FC (FC-Corr) as shown in B. Cyan, before GSR. Blue, after GSR. Large deviations that changed the pattern of two time courses were occasionally observed (C, Upper), suggesting that GSR altered the spatial pattern of HemoS at some time points. (Lower Left) Scatterplot comparing time courses FC-Corr before and after GSR. The same scan as used in Upper (but for all time frames in the scan). (Lower Right) Histogram of differences between the two time courses of FC-Corr in each frame (n = 1,500 frames). Dotted gray line indicates mean (mean = 2.5 ×10−4). Same scan as used in Lower Left. (D) Distribution of the spatial correlations between FC before and after GSR (n = 259 pairs). (Upper) Ca-FC. (Lower) Hemo-FC. (Insets) Mean spatial correlation within each mouse (mean ± SD, 0.70 ± 0.19 for Ca-FC, and 0.86 ± 0.040 for Hemo-FC; n = 7). +, P < 10−4. ++, P < 10−9 (t test, n = 7 mice). Error bars, SEM. (E) Histogram of correlation between the time courses of FC-Corr before and after GSR (n = 672 pairs of scan seed in seven mice). (Upper) CaS. (Lower) HemoS. (F) Histogram of the percent of motifs that were also detected as a motif after GSR (n = 672 pairs of scan seed in seven mice). (Upper) CaS. (Lower) HemoS. (G and H) Pr(follower Hemo) before and after GSR as a function of motif strength (G) and BV signal (H). Mean across mice, n = 7. Shaded region, SEM. Dotted line, mean before GSR. *P < 0.036. **P < 0.019. (I and J) Pr(leader Ca) before and after GSR as a function of motif strength (I) and BV signal (J). Mean across mice, n = 7. Shaded region, SEM. Dotted line, mean before GSR.

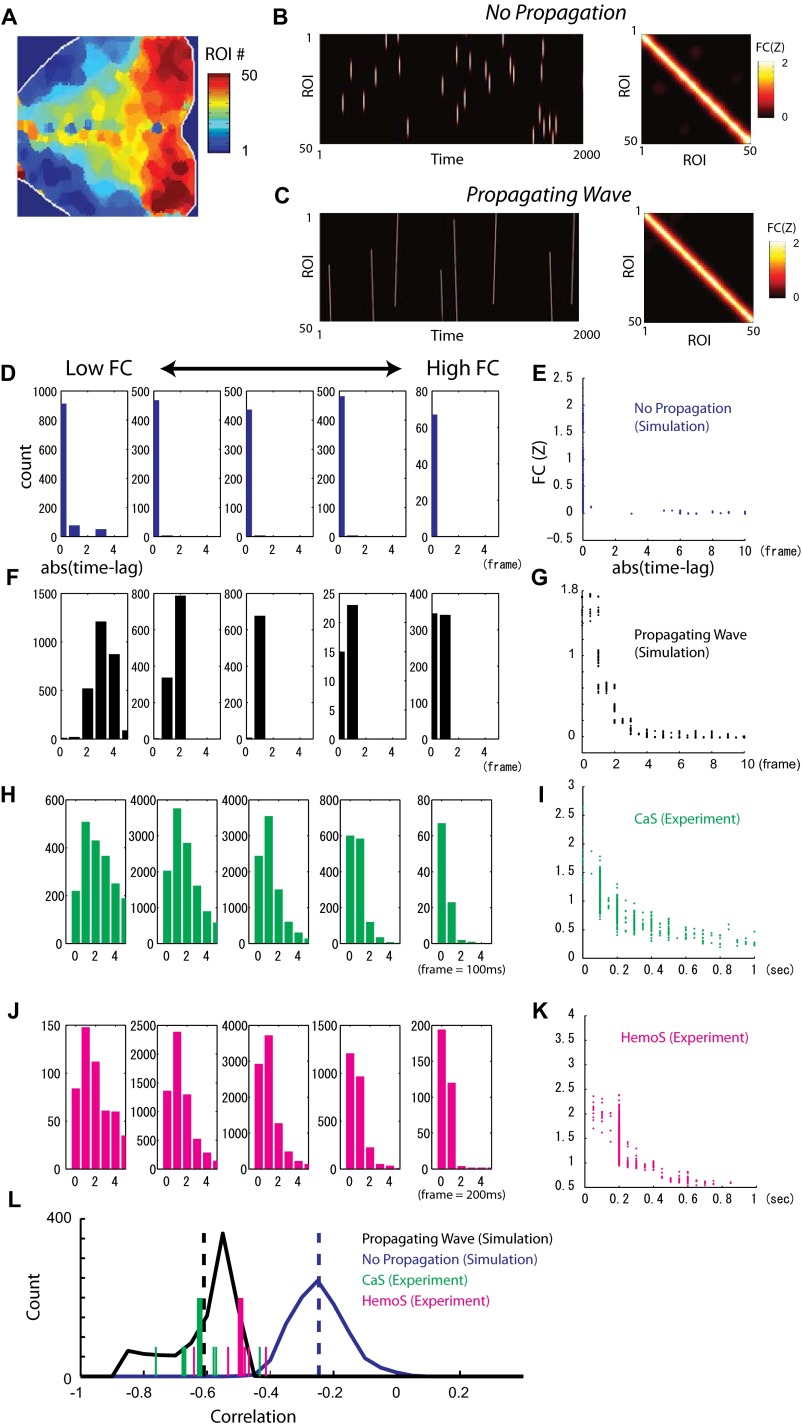

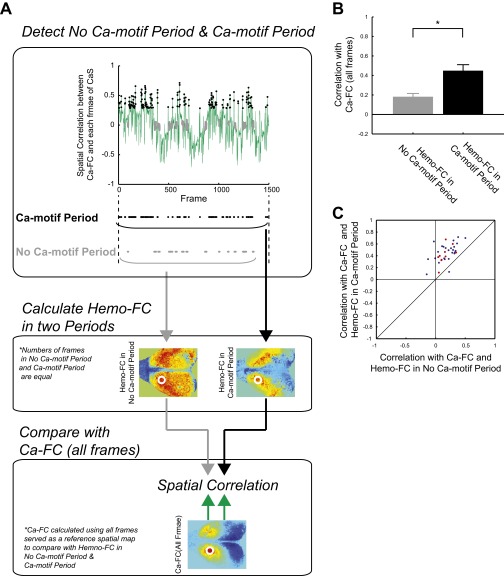

Coactivations in CaS Were Necessary to Set Spatial Patterns of Hemo-FC.

Finally, we asked whether the presence of Ca motifs was indeed necessary for setting the spatial pattern of Hemo-FC. The hypothesis is that the similarity between Ca-FC and Hemo-FC is derived from the similarity between Ca-FC (using all of the frames) and Hemo-FC during Ca motifs. A prediction according to this hypothesis is that if we take the time period when Ca motif is absent, then the spatial similarity between Ca-FC and Hemo-FC during this period should be low. To quantitatively examine this prediction, we defined a no-Ca motif period for each anatomical seed as the sustained time period (>2.5 s) when the spatial correlation between Ca-FC and the activity patterns in each CaS-frame was continuously low (Fig. S9A). To compare with no-Ca motif period, we also defined a Ca motif period by selecting the same number of frames but with high spatial correlation with Ca-FC. Note that the selection of a no-Ca motif period and Ca motif period only uses CaS and does not rely on similarity between Ca-FC and Hemo-FC. We then calculated Hemo-FC separately for a no-Ca motif period and a Ca motif period and compared each of them with Ca-FC calculated using all of the frames (Fig. S9A). Consistent with our hypothesis, the spatial correlation between Ca-FC and Hemo-FC during the no-Ca motif period, averaged across seeds for each animal, was low (0.059 ± 0.054, mean ± SEM) and significantly smaller than that calculated using Hemo-FC during the Ca motif period (0.34 ± 0.040, mean ± SEM; P < 0.034, paired t test; Fig. 5A). The difference was insensitive to the level of threshold for detecting a no-Ca motif period (Fig. S9B) and was consistent across anatomical seeds (Fig. S9C). These results suggest that the presence of Ca motifs was necessary for setting the spatial patterns of Hemo-FC.

Fig. S9.

Hemo-FC in the no-Ca motif period and Ca motif period. (A) Schematic drawings showing the procedure for comparing Ca-FC with Hemo-FC in the no-Ca motif period and with Hemo-FC in the Ca motif period. (Top) For each scan, the spatial correlation between the Ca-FC of a chosen ROI and CaS in each frame was calculated for all of the frames in the scan (green trace). Next, the time periods in which the correlation value was continuously low were detected (gray dots) and defined as the no-Ca motif period. Finally, the Ca motif period was defined by taking the first to Nth frames with the highest correlation value (black dots), where N was the number of frames in the no-Ca motif period. Raster plots (Bottom) show frames corresponding to the Ca motif period (black) and no-Ca motif period (gray). Note that the numbers of black dots and gray dots are equal. (Middle) After shifting the no-Ca motif period and Ca motif period for 2 s to account for the hemodynamic delay, the Hemo-FC was calculated using frames corresponding to the no-Ca motif period (Left) and Ca motif period (Right). (Bottom) Spatial correlations were calculated between Ca-FC using all the frames and Hemo-FC calculated using frames in no-Ca motif period (or frames in Ca motif period). (B) Correlation between Ca-FC (all frames) and Hemo-FC in the no-Ca motif period and Hemo-FC in the Ca motif period. Same as Fig. 5A but for a different threshold for detecting no-Ca motif period (for each animal, frames with lowest 15% of the absolute value of correlation coefficient was detected. Then, sustained periods >2.5 s were defined as the no-Ca motif period with the first 2 s of each period discarded). Mean across mice (n = 7). Error bars, SEM. *P < 0.001 (paired t test). (C) Scatterplot comparing correlation between Ca-FC (all frames) and Hemo-FC in the no-Ca motif period (x axis) and Hemo-FC in the Ca motif period (y axis) for individual seeds. The threshold for no-Ca motif period detection was the same as in B. Red dots indicate seeds that were selected for the analysis of motifs. Blue dots indicate other seeds. Diagonal black line indicates x = y.

Fig. 5.

Ca motifs were necessary for Hemo-FC. (A) Spatial correlation between Ca-FC calculated using all of the frames and Hemo-FC in no-Ca motif period and Hemo-FC in Ca motif period. The mean across mice in which no-Ca motif period was found (n = 4). Error bars, SEM. *P < 0.036 (paired t test, n = 4 mice). (B) Schematics of the relation among neuronal activity, coactivations in CaS, coactivations in HemoS and Hemo-FC.

SI Text

SI Materials and Methods

Animals.

Emx1-IRES-cre and Ai38 (38) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. These mice were crossed, and all of the cortical excitatory neurons of the pups expressed GCaMP3. Mice (P60–P90) were prepared for in vivo wide-field simultaneous imaging. Anesthesia was induced with isoflurane [3% (vol/vol)] and maintained with isoflurane [1–2% (vol/vol) in surgery, 0.5–0.8% during imaging] and chlorprothixen (0.3–0.8 mg/kg, i.m. injection). A custom-made metal head plate was attached to the skull using dental cement (Sun Medical Company, Ltd.), and a large craniotomy was made over the whole cortex. The posterior edge was along a lambdoid suture, and both lateral edges were along a lateral suture. The anterior edge was made over the olfactory bulb. After opening the scalp, we stopped the bleeding with a Spongel (Astellas Pharma Inc.), and the underlying cortex was cleared with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, and 10 mM Hepes pH 7.4). The craniotomy was sealed with 1% agarose and a glass coverslip. During the imaging, body temperature was maintained by a heat pad.

Simultaneous Calcium and Intrinsic Signal Imaging.

Simultaneous imaging of calcium and intrinsic signals in vivo was performed using a macro zoom fluorescence microscope (MVX-10; Olympus) or an upright fluorescence microscope (ECLIPSE Ni-U; Nikon) equipped with a 1× objective (1× MVX Plan Apochromat Lens, N.A. 0.25; Olympus or CFI Plan UW 1×, N.A. 0.04; Nikon). A 625-nm LED light source was used to obtain intrinsic signals. GCaMP3 was excited by a 100-W mercury lamp through a GFP mirror unit (Olympus). Intrinsic signal data were collected at a frame rate of 5 Hz using a CCD camera (1,000 m; Adimec) controlled by an Imager3001 system (Optical Imaging Ltd.). A square region of cortex that was 11.6 mm on each side was imaged at 332 × 332 pixels. Calcium signal data were collected at a frame rate of 10 Hz using a cooled CCD camera (DS-Qi1Mc; Nikon) controlled by NIS-elements BR (Nikon). A rectangle region of cortex 13.3 × 10.0 mm was imaged at 320 × 240 pixels. To acquire these signals simultaneously, the dual port (U-DP; Olympus), which separated emission signals with a dichroic mirror, was equipped and two CCD cameras were attached to each port. The emission filters were 625-nm long-pass (SC-60; Fuji Film) for intrinsic signal, and 505–535 nm bandpass (FF01-520/35-25; Semrock) for calcium signals. To synchronize the timing of data acquisition, NIS motifs sent TTL (transistor–transistor logic) pulses to the Imager3001 as the signal to start imaging. Data were acquired for 30–60 min from each animal (5 min per scan).

Data Preprocessing.

All data analyses were conducted using MATLAB (MathWorks). For both CaS and HemoS, all of the image frames were corrected for possible within-scan motion by rigid-body transformation. CaS images and HemoS images were then coregistered by rigid-body transformation using manually selected anatomical landmarks that were visible in both images (e.g., branching points of blood vessels). All of the images were then spatially down-sampled by a factor of two. Pixels within the cortex (at this point including large blood vessels, including the sinus) were extracted manually. For both CaS and HemoS, slow drift in each pixel’s time course was removed using a high-pass filter (>0.01 Hz, second-order Butterworth. No low-pass filter was used). For the analysis of infra-slow signals (Fig. S10), a bandpass filter (0.01–0.1 Hz, second-order Butterworth) was used. After filtering, each pixel’s time course was normalized by subtracting the mean across time and then dividing by the SD across time. Finally, HemoS was multiplied by −1 to set the polarity of the activity change in CaS and HemoS as equal.

Fig. S10.

Analysis of infra-slow (0.01–0.1 Hz) activity. (A) Cross-correlation between CaS and HemoS in the infra-slow range. Same convention as in Fig. 1B. (B) Similarity between the spatial maps of Ca-FC and Hemo-FC in the infra-slow range. Same convention as in Fig. 1D but for infra-slow CaS and infra-slow HemoS. (C) Example of GBA in infra-slow CaS. Note that GBA started in the anterior areas and then propagated to posterior areas. (D) Examples of Ca motifs and Hemo motifs in infra-slow range. Same convention as in Fig. 3A. (E) A representative scatterplot showing correlation between ROI-wise TD in CaS and HemoS at the infra-slow range for one animal (R = 0.44, P < 0.0001). Same convention as Fig. S2, A2. (F) ROI-based FC matrix for infra-slow CaS. Mean across seven mice. (G) ROI-wise correlation of TD profiles in infra-slow CaS. Correlation coefficient between the off-diagonal and unique values in the matrices shown in F and G was 0.64 (P < 0.0001). (H) ROI-based FC matrix for infra-slow HemoS. Mean across seven mice. (I) ROI-wise correlation of TD profiles in infra-slow HemoS. Correlation coefficient between the off-diagonal and unique values in the matrices shown in H and I was 0.64 (P < 0.0001).

GSR was performed in some analyses using the standard procedure described in the fMRI literature (47). First, pixels corresponding to the cortex were extracted from the brain mask constructed above by removing pixels corresponding to the BV using an intensity threshold adjusted manually for each animal. Second, time courses of gray matter pixels were averaged across pixels to obtain the GS time course for each scan. Finally, the time course of GS was regressed out from each pixel’s time course using linear regression. HemoS in the pixels corresponding BV was averaged to obtain the BV signal.

Analysis of ROI Time Courses.

To define ROIs, 38 cortical regions (19 for each hemisphere) were selected based on a previous mouse functional connectivity study (43). Next, stereotaxic coordinates of the centers of selected areas were extracted by referring to the mouse brain atlas (56) (Fig. S1A). The center coordinates of selected areas were then mapped to CaS and HemoS images (reference point was set at the intersection of the inferior cerebral vein and the midline). Each ROI was a 6 × 6 pixel square (0.5 × 0.5 mm) centered at a selected coordinate. The time course for each ROI was calculated by averaging the time courses of pixels within the ROI that corresponded to gray matter (i.e., time courses of BV and out-of-brain pixels were discarded if such pixels were present in the ROI). In some animals, ROIs located outside of the FOV were discarded. Cross-correlation between simultaneously recorded CaS and HemoS was obtained for each ROI by calculating the correlation coefficients between the time course of CaS and the time-shifted time course of HemoS (−10 to 10 s at 1-s step).

Analysis of FC Maps.

For both Ca-FC and Hemo-FC, the strength of FC was calculated using a standard seed-based correlation method (47). First, the correlation coefficient between the time course of a selected ROI (seed time course) and the time course of every pixel within the brain was calculated. Second, correlation coefficients were Z-transformed to obtain the FC value of the pixel for each scan. Third, FC values were averaged across scans to obtain FC values for each pixel. The spatial correlation between a Ca-FC map and a Hemo-FC map was calculated by taking the pixel-by-pixel correlation coefficient between the two maps using all of the gray matter pixels.

Detection of GBA.

For each CaS scan, we first calculated the time course of the percent active pixels as follows. For each pixel in each frame, the pixel was defined as active when the (normalized) signal of the pixel exceeded the threshold (1 SD). Then, for each frame, the proportion of active gray matter pixels was calculated.

Periods corresponding to GBA were detected using the time course of the proportion of active pixels as follows. First, peaks of the time course whose height exceeded 0.5 were detected. Second, for each peak, the closest frame before the peak frame that first fell below 0.05 was detected and the frame next to the detected frame was defined as the start frame of GBA. Third, for each peak, the closest frame after the peak frame that first fell below 0.05 was detected, and the frame just before the detected frame was defined as the end frame of GBA. Fourth, if two peaks that both exceeded the peak height of 0.5 and were separated by a trough whose height was below 0.1 were found in a GBA, the GBA was separated into two GBAs at the trough frame. For each GBA, the duration was calculated as the length of GBA in time, and the size was calculated as the maximum proportion of active pixels reached in the GBA period. The analysis for the propagation direction of GBA is described in Fig. S4A.

Analysis of Activity Propagation.

To detect CaS transients, each time course was first bandpass-filtered at (0.1–2 Hz, second-order Butterworth) to remove slow drifts and high-frequency noise. Derivatives of the filtered time courses were calculated and peaks exceeding the threshold (1 SD) were defined as CaS transients. For selecting AP-GBA, we first searched for GBA with a bias index (Fig. S4A) greater than 0.5. We then used the maximum transient that occurred between the start frame and peak frame of the GBA. The time lag between a pair of ROIs was calculated as follows: one ROI was assigned as a seed ROI and the other ROI as a pair ROI. For each transient in the seed ROI (seed transient), a transient in the pair ROI that occurred closest in time to the transient in the seed ROI was searched and marked as the pair transient. Each transient in the pair ROI could be a pair transient of only one seed transient. For each scan and each pair of ROIs, the difference in the time of the seed and the pair transients was calculated for all of the detected transient pairs. For the analysis of AP-GBA, only transients that occurred between the start and the peak frames of AP-GBA were used. A time lag in a pair of ROIs was then calculated as the mean of the time difference. A time lag in the AP direction (Fig. 2G) was calculated by setting the time lag in the anterior-to-posterior direction to positive; if the seed ROI was located posterior to the pair ROI, a negative time lag between the pair was considered as a positive time lag in the AP direction. To examine the robustness of the result to variation of thresholds, the same calculations were conducted using different threshold values for the minimum size of GBA [peak height = (0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7)] and the directionality of GBA [bias index = (0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7)]. The effect of distance between ROIs was accounted for by taking the partial correlation between the time lag in the AP direction and Ca-FC with the distance between ROIs in the anteroposterior axis as the controlling variable. The abs(time lag) was calculated as the median of the absolute value of the time lag across all pairs of transients occurred in the scan. Because spontaneous CaS transients were reflected in HemoS (Fig. S1B), we also applied the same procedure described above to the analyses using HemoS.

Analysis of activity propagation using a method recently developed by Mitra and coworkers (29–31) was conducted as described previously and the same procedure was used for both CaS and HemoS. Briefly, cross-covariance between time courses was calculated for each pair of ROIs (Fig. S2, A1 and A2). Time courses are preprocessed as described above. GSR was not used (see SI Discussion, Effects of GSR on the Coupling Between CaS and HemoS, for rationales). Peak of the cross-correlation was used as time delay (TD) between the ROI pair. Because sampling rate in our experiment was high (10 Hz for CaS and 5 Hz for HemoS), we did not use parabolic interpolation. To obtain TD of a ROI pair for one animal, TD was calculated for each scan and then averaged across scans. To obtain average TD across animals, TD for each animal was averaged across animals. Absolute TD (Fig. S2, A3 and A4) was calculated by taking the absolute value of TD. To calculate the ROI-wise correlation structure of TD (Fig. S2 C and E), each column of the TD matrix was considered as a TD profile of the ROI corresponding to the column. Then, for all pairs of ROIs, the correlation coefficient between TD profiles was calculated.

Analysis of Motifs.

Analyses of motifs were adapted from the procedure developed by Mohajerani et al. (28). Briefly, for each ROI, we calculated the pixel-by-pixel correlation between the Ca-FC (Hemo-FC) map of the ROI and CaS (HemoS) in each frame using all gray matter pixels. Frames in which the spatial correlation value exceeded a threshold value (top 10th percentile of correlation values across all scans and ROIs) were defined as motif frames (i.e., Ca motifs or Hemo motif). For this calculation, we selected 10 ROIs from the original set of 38 ROIs (five per hemisphere; the same set of anatomical ROIs as used in the previous study) (28). For each Ca motif (Hemo motif) of a selected ROI occurring at time t, if the Hemo motif of the same ROI was detected between t + 1 to t + 5 s (t − 5 to t − 1 s), then the detected motif was marked as a follower-Hemo motif (leader-Ca motif). For control analyses, follower-Hemo motifs and leader-Ca motifs were detected by the same procedure described above but using CaS and HemoS data shifted by one trial.

The motif strength was assigned to each Ca/Hemo motif by calculating the pixel-by-pixel correlation between the activity pattern in the motif frame and the FC map corresponding to the motif. Then, to allow comparisons across animals, motif strengths were classified into 10 levels (linearly dividing between the minimum motif strength and maximum motif strength into 10 segments). Similarly, the strength of the BV signal for each motif frame was calculated by taking the value of the BV signal at the motif frame. Then, to allow comparisons across animals, the obtained BV signals were classified into 10 levels (linearly dividing between the minimum and maximum BV signal into 10 segments).

For each of the anatomical ROIs shown in Fig. S1A, the no-Ca motif period in each scan was detected by finding periods in which the spatial correlation between Ca-FC of the ROI and the spatial pattern of CaS in each frame was continuously low (correlation coefficient between −0.05 and 0.05 for >2.5 s). The first 2 s in the continuous period were discarded to remove the influence on HemoS from the preceding neuronal activity. Then, for each scan in which no-Ca motif periods (k frames) were detected, the Ca motif period was defined as the top k frames with the highest correlation values. To calculate the Hemo-FC in a no-Ca motif period (or a Ca motif period) for each scan, the a no-Ca motif period (or a Ca motif period) was detected as described using CaS that were time-shifted by +2 s to account for the hemodynamic delay. Hemo-FC in the no-Ca motif period (or Ca motif period) was then calculated using all no-Ca motif period (or Ca motif period) frames detected in the scan. Hemo-FC calculated for the no-Ca motif period (or Ca motif period) was averaged across those scans in which at least one no-Ca motif period was present. Scans with no detected no-Ca motif period were discarded.

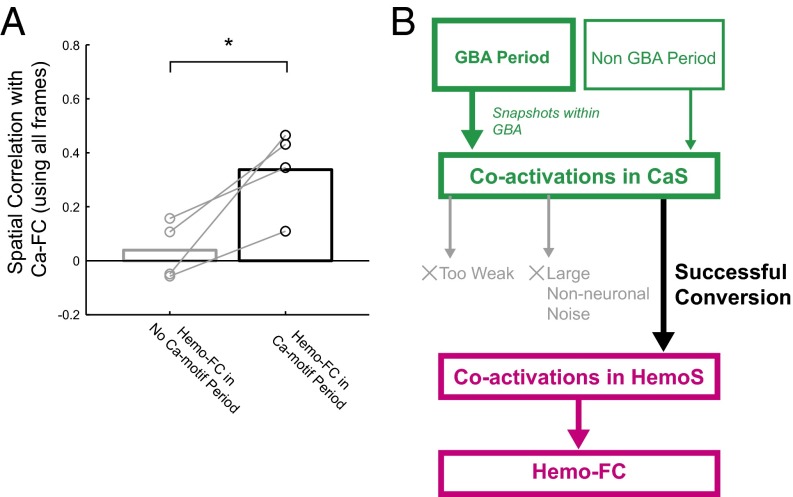

Discussion

Using simultaneous wide-field imaging of CaS and HemoS, we investigated whether and how the brain-wide spatiotemporal dynamics of spontaneous neuronal activity were converted into the spatial patterns of Hemo-FC. The present results collectively indicate a scenario connecting the spatiotemporal dynamics of spontaneous neuronal activity and a particular spatial pattern of Hemo-FC (Fig. 5B; see SI Text for further discussion). First, propagating spontaneous neuronal activity results in synchronous neuronal coactivations across brain areas connected with high Ca-FC. Such coactivations in CaS, often embedded in GBA, are then converted into spatially similar coactivations in HemoS under the conditions that the coactivations in CaS are strong enough (Fig. 4B) and large nonneuronal noise is absent (Fig. 4D). Finally, a seed-based temporal correlation gives rise to the spatial pattern of Hemo-FC by collecting the spatial information of the coactivations in HemoS [Fig. 5A; and see Fig. S10 and SI Text for similar results in infra-slow range (0.01–0.1 Hz)].

Though previous electrophysiological and imaging studies reported heterogeneous large-scale dynamics of spontaneous neuronal activity (21–28), considerable numbers of studies using different experimental setups repeatedly observed waves of neuronal activity similar to GBA (16, 21–26), suggesting that GBA is a dominant type of dynamics in the resting cortical network. Given the prevalence of GBA, its relationship to Hemo-FC in the resting state has been underappreciated. By simultaneously imaging CaS and HemoS, we found evidences that GBA is indeed linked to Hemo-FC. First, the frequency of GBA was within the range of frequency band considered to be most relevant for Hemo-FC in the resting state (Fig. 2B) (44, 45). Second, and more importantly, GBA recruited specific spatial patterns of neuronal coactivations that ultimately contributed to the spatial patterns of Hemo-FC (Fig. 3C and Fig. 5A). By showing the link among GBA, neuronal coactivations, and Hemo-FC, the present study brings together a broad range of studies, from VSD imaging in mice to resting-state fMRI in humans, and forms the basis to understand them on a unified basis.

It is important to note that the present results are derived from lightly anesthetized mice. Spontaneous activity in the infra-slow range could be modulated by behavioral state of the animal (31, 48). Thus, particular propagation structures found in the present study under anesthesia, such as anterior-to-posterior propagation of GBA (see below for further discussion), could appear different in awake states. Nevertheless, it is also known that resting-state networks persist across various behavioral states, including wakefulness, natural sleep, and anesthetized state (28, 49–51), and similar dynamics such as coactivation of resting-state network (RSN) (28, 49) and GBA (52), exist both in anesthetized and awake states. In addition, the use of anesthesia can eliminate potential effects of body movement that is known to contaminate estimation of FC in wake states (53).

Physiological significance of GBA still remains an open question, but there exist some hints in recent literature. An electrophysiology-triggered fMRI showed global neocortical activation similar to GBA associated with hippocampal ripples (52). Consistently, a calcium imaging study in mice reported large-scale flow of spontaneous CaS (22) that resembled anterior-to-posterior propagation of neuronal activity during sharp-wave ripples (23). A recent fMRI study also found anterior-to-posterior bias of activity propagation during slow wave sleep (31). Consistent with these studies, we found moderate but significant bias toward anterior-to-posterior propagation of activity in GBA. These reports collectively indicate a potential role of GBA in brain-wide memory consolidation associated with the ripples (54). The close relationship between the activity propagation during spindle waves and RSNs found in the present study (Fig. 2 E–G) would be important for understanding brain-wide memory consolidation. Because several fMRI studies have reported changes in Hemo-FC after task learning (7, 55) and during sleep (8), it is of great interest for future studies to see how the behavioral context influences the dynamics of GBA as well as Hemo-FC arising from it. Application of wide-field imaging to awake mice (21) would be useful to investigate these questions.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic mice expressing GCaMP3 in excitatory neurons (38) (P60–P90) were prepared for in vivo wide-field simultaneous imaging. Simultaneous imaging of calcium and intrinsic signals in vivo was performed using a macro zoom fluorescence microscope (MVX-10; Olympus). Calcium and intrinsic signals were recorded at 10 Hz and 5 Hz, respectively. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the institutional animal welfare guidelines laid down by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyushu University. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Kyushu University.

SI Discussion

Model-Based Analysis of Propagating and Nonpropagating Spontaneous Activity.

This section describes model-based analysis of the contribution of two types of spontaneous activity: propagating activity and nonpropagating activity. As shown below, the two types of activity are indistinguishable from the maps of FC, but can be distinguished examining the relationship between the distribution of time lags in the activity and FC between two areas.

For visualization of the simulated activity, we first made ROIs from the smoothed spatial map of peak time (Fig. 2F). Pixels in the map of peak time were binned into 50 bins with equal numbers of pixels. Then each bin was assigned as one ROI (Fig. S6A). Each wave of propagating and nonpropagating activity was modeled by Eqs. S1 and S2, respectively.

| [S1] |

| [S2] |

k and t denote ROI number (1–50) and time, respectively. Parameters for propagating and nonpropagating waves were set to (σk, σt) = (2, 2) and (σk, σt, V) = (2, 25, 2), respectively. In each simulated scan, waves with randomly positioned centers appeared at random time (Movies S3 and S4). The number of propagating waves in one simulated scan (5,000 frames) was set to 25 based on the experimental results of GBA (∼0.05 Hz with wave duration of ∼5 s). The number of nonpropagating waves was determined so that the sum of activity across all pixels and frames was approximately equal in scans with propagating waves (difference in the sum of activity <5%). As in the experimental data, FC between pixels was calculated with a temporal correlation method and then was Fisher Z-transformed (Fig. S6 B and C). The similarity of FC in the scans with propagating and nonpropagating waves was ensured by setting the correlation coefficient between the two FCs >0.95. Detection of the spike-like transients in each pixel and time lag between each pixel pair was conducted using the same procedure as in the experimental data (search window for the time lag in simulations was set to 75 frames).

For each experimental or simulated scan, the distribution of abs(time lag) for each pair of ROIs (or pixels) was obtained by having the distribution of the absolute value of the time lag. All of the pairs of ROIs were then binned into five groups according to the strength of the FC. Distributions of abs(time lag) in the same group were concatenated to obtain the distribution of the abs(time lag) for the group. The scatterplot comparing abs(time lag) and FC for each scan was obtained by taking the median of the distribution of abs(time lag) for each pairs of ROIs (or pixels).

The results of the simulations suggested that one can use the relationship between abs(time lag) and FC to distinguish between propagating and nonpropagating activity even when the FC for propagating and nonpropagating activity are highly similar (R > 0.99 for the case shown in Fig. S6 B and C). In the case of nonpropagating activity, the center of the distribution of abs(time lag) was always at zero regardless of the strength of FC between pairs of pixels (Fig. S6D). By contrast, in the case of propagating activity, the center of the distribution of abs(time lag) took values larger than zero when the pairs of pixels had low FC, and shifted toward zero as the FC increased (Fig. S6F). The relationship between abs(time lag) and FC was also evident in the scatterplot comparing the median of abs(time lag) and FC for each pair of pixels (Fig. S6 E and G). Experimental results for CaS and HemoS clearly resembled the simulation with propagating activity (Fig. S6 H–K).

To quantitatively compare the experimental results for each animal with simulations, for each pair of ROIs (or pixels), we first calculated the median abs(time lag) across scans [i.e., medianAcross Scan(medianEach Scan[abs(time lag)])] and the mean FC across scans (Fig. 2H). For each animal, we used all scans for each animal. For each run of simulation, we used three simulated scans. Then, we calculated the correlation coefficient between abs(time lag) and FC across pairs of ROIs (or pixels). Pairs having zero abs(time lag) and zero FC were excluded when calculating the correlation coefficient. The distribution of the correlation coefficients for each type of simulation (propagating and nonpropagating) was obtained by running the simulation 1,000 times (Fig. S6L). The mean values of the correlation for experimental data were significantly different from those of simulations without propagating activity (P < 0.001 for both CaS and HemoS) but not from those of simulations with propagating activity (P > 0.6 for CaS and P > 0.03 for HemoS). These results corroborated the notion that experimentally observed FC originated from propagating spontaneous activity.

It should be noted, however, that some CaS transients occurring with zero time lag were observed between ROI pairs having high Ca-FC (Figs. S5B and S6 H and J), suggesting that some of the Ca motifs may have occurred without activity propagation detectable at our frame rate (10 Hz). Therefore, although the present results suggest a significant contribution from propagating spontaneous activity, we cannot exclude potential contributions from nonpropagating spontaneous activity. Future experiments using wide-field imaging at a higher frame-rate and GCaMP with fast kinetics may clarify theses point.

Effects of GSR on the Coupling Between CaS and HemoS.

The following describe the effect of GSR, i.e., removal of signal averaged across the whole brain from each pixel’s time course (47), on the spatiotemporal patterns of CaS and HemoS as well as the coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs. Fig. S8A shows an example of HemoS and maps of Hemo-FC before and after GSR. From the time course of each pixel (Fig. S8A, Top), GS (Middle) was regressed out to obtain the time course after GSR (Bottom). Spatial maps of Hemo-FC before (Fig. S8B, Left) and after GSR (Center) appeared similar. Although the mean Hemo-FC was shifted toward zero after GSR, pixel-wise comparison of Hemo-FC before and after GSR was significantly correlated (R = 0.86, P < 10−4; Fig. S8B, Right).

We found that GSR retained overall similarity between spatiotemporal dynamics of CaS and HemoS as well as between spatial patterns of Ca-FC and Hemo-FC. Fig. S8C shows time courses of the correlation between the activity pattern in each frame of Hemo-S and a selected map of Hemo-FC (FC-Corr). Large deviations that changed the pattern of two time-courses were occasionally observed (Fig. S8C, Upper, arrows), suggesting that GSR altered the spatial pattern of HemoS at some time points. Nevertheless, time courses of the correlations between spatial patterns of activity and FC maps before and after GSR were positively correlated (Fig. S8C, Lower Left; R = 0.90, P < 10−4). Fig. S8C, Lower Right, shows the histogram of differences between the two time courses of FC-Corr in each frame (n = 1,500 frames). Consistent with the visual impression, although some frames exhibited large differences in FC-Corr (>0.25 or <−0.25), the mean of the histogram was close to zero (mean = 2.5 ×10−4), suggesting that GSR did not strongly alter the spatial patterns of HemoS at each frame.

Fig. S8 D and E shows that the spatial correlations between FC before and after GSR for all of the scans of CaS and HemoS (n = 259 scans each). A high spatial correlation between Hemo-FC before and after GSR was observed across seeds and was also observed for Ca-FC, suggesting that GSR did not significantly alter the spatial structure of Ca-FC and Hemo-FC (Fig. S8D). This tendency was consistent across animals (P < 10−4 and P < 10−9, respectively, for Ca-FC and Hemo-FC, t test, n = 7). Similarly, the histogram of correlation between the time courses of FC-Corr before and after GSR (Fig. S8E, Lower Right; n = 672 pairs of scan seeds in seven mice) shows that high spatial correlation between the time courses of FC-Corr before and after GSR was observed across seeds both for CaS and HemoS. These results suggest that GSR did not significantly alter the spatial structure of the moment-to-moment activity with respect to FC.

Fig. S8F shows the histograms of the percent of motifs in each scan that were also detected as a motif after GSR (n = 672 pairs of scan seed in seven mice). On average, 55 ± 4.2% of Ca motifs and 64 ± 4.3% of Hemo motifs found before GSR were also detected as motifs after GSR [mean ± SEM, n = 7 mice; Note that the total numbers of detected motifs were equal for both datasets (see SI Materials and Methods for details). Consistent with the notion that GSR did not strongly alter the spatiotemporal pattern of CaS and HemoS, the timing of the detected motifs before and after GSR was still largely overlapping.

Importantly, GSR significantly improved the coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs. Pr(follower Hemo) as a function of motif strength before and after GSR significantly increased after GSR (two-way ANOVA with GSR and motif strength as factors. P < 0.036 and P < 0.003 for the main effect of GSR and motif strength, respectively. No significant interaction, P > 0.55; Fig. S8G). Notably, after GSR, Pr(follower Hemo) approached 75.6% for Ca motifs with the highest level of motif strength. Similarly, Pr(follower Hemo) as a function of BV signal before and after GSR significantly increased after GSR (two-way ANOVA with GSR and BV signal as factors. P < 0.019 and P > 0.34 for the main effect of GSR and BV signal, respectively. No significant interaction, P > 0.92; Fig. S8H). These results suggested that GSR improved detection of Hemo motifs that were previously masked by nonneuronal HemoS. However, Pr(leader Ca) did not significantly change after GSR, suggesting that GSR did not significantly affect the detection of Ca motifs (two-way ANOVA with GSR and motif strength as factors. P > 0.58 and P < 0.008 for the main effect of GSR and motif strength, respectively. No significant interaction, P > 0.99; two-way ANOVA with GSR and BV signal as factors. P > 0.91 and P > 0.64 for the main effect of GSR and BV signal, respectively. No significant interaction, P > 0.82; Fig. S8 I and J). The contrasting effect of GSR on Pr(follower Hemo) and Pr(leader Ca) suggested that GSR improved the detection of Hemo motifs that were masked by nonneuronal noise but did not improve the detection of Ca motifs, possibly because CaS was less affected by nonneuronal noise. In sum, these results suggest that GSR improved coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs while largely preserving spatiotemporal patterns of CaS and HemoS.

There were several reasons that we chose not apply GSR in the preprocessing. First, we found positive correlation between GS in CaS and GS in HemoS (Fig. S3C) at a time lag comparable to the hemodynamic delay obtained with sensory stimulation (Fig. S1C). This result suggests that, as has been reported in a previous study (16), GS in HemoS contains a neuronal component. Second, we considered that inclusion of GSR affects one of our key interests in the present study—i.e., to examine how GBA contributed to FC. Indeed, in the data processed with GSR, only two time epochs in the entire data satisfied criteria for GBA. We note that it could be possible that other criteria for GBA detection, such as ones that use propagation information instead of the activity-level in the brain, recover GBA from data processed with GSR. However, searching for such alternative criteria is beyond the scope of the present study. Third, as in recent studies of resting-state FC using wide-field imaging in mice (20, 28, 57), we were able to obtain spatially specific patterns of FC without applying GSR, both in CaS and HemoS (Fig.1C). Moreover, the spatial patterns of FC before and after GSR were similar and showed high spatial correlation both in CaS and HemoS (Fig. S8 B and D). Fourth, inclusion of GSR is still a controversial issue in fMRI (58). Because of these reasons, we chose not to include GSR in our preprocessing.

The present results provide important implications for key methodological issues in resting-state fMRI. There is controversy over the use of GSR as a noise-reduction procedure (58). The present results indicate that a large portion of Hemo-GS indeed had a neuronal origin (Fig. S3 A and C) (16). Nevertheless, the present results also suggest that GSR significantly improved coupling between Ca motifs and Hemo motifs by suppressing nonneuronal noise in HemoS (Fig. S8). Overall, our results provided support for the use of GSR as a convenient tool to reduce nonneuronal noise in HemoS. To what extent GSR preserves underlying neuronal activity remains an important issue, which is beyond the scope of this study.

An Alternative Scenario for the Relationship Between Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Neuronal Activity and FC.

An alternative scenario is that Hemo-FC appears as a result of spontaneously emerging transient synchronization and desynchronization of activity across distant areas (i.e., alternating activation of nonpropagating coactivations) (28). The results of our model-based analysis (Fig. S6), as well as the fact Ca motifs mostly appeared during GBA (Fig. 3C), argue that contribution of such nonpropagating coactivations are minor compared with coactivations arising from propagating activity. We note, however, that the results did not exclude the presence of minor contributions from the nonpropagating coactivations (non-GBA period in Fig. 5B and Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results suggested that transient neuronal coactivations embedded in the propagation of GBA are essential neuronal events that set the spatial structure of Hemo-FC.

SI Results

Propagation Analysis Using the Cross-Covariance Method.

To further examine the relationship between activity propagation and FC in CaS and HemoS, we conducted analysis recently developed by Mitra and coworkers (29–31). We found that TD matrices derived from CaS and HemoS (Fig. S2, A1 and A2) showed significant positive correlation (R = 0.31 ± 0.05, mean ± SEM, n = 7. P < 0.002, t test). Furthermore, consistent with the previous study (30), we found that the ROI-wise correlation structure of TD was significantly correlated with ROI-wise FC (Fig. S2 B–D; R = 0.62 and 0.63 for CaS and HemoS, respectively. P < 0.0001 for both; see SI Materials and Methods for details). Finally, we found that the ROI-wise correlation structure of TD in CaS and HemoS was also significantly correlated (R = 0.51, P < 0.0001). These results are also valid for infra-slow signals (Fig. S10 F–I). Taken together, these results corroborate the notions that propagation structure in CaS and HemoS corresponded with each other, and the relation between spontaneous activity propagation and FC are general phenomena in the data. In the following, we compare the present findings with findings by Mitra and coworkers (29–31).

Recently, Mitra and coworkers (29–31) devised a novel analysis to investigate propagation structure of resting-state fMRI in the whole brain. By showing correlation between the propagation structures in CaS and HemoS (Fig. S2, A2), the present results suggest that the propagation structure in HemoS derived using Mitra’s methodology is not a mere vascular artifact but likely to reflect the propagation structure of underlying neuronal activity. Moreover, consistent with Mitra and coworkers (30), we observed significant relation between the propagation structure and FC both in CaS and HemoS (Fig. S2 B–E). These results corroborate the notion that the propagation of spontaneous activity is an important factor to understand the origin of resting-state FC.