Abstract

The so-called “insight paradox” posits that among patients with schizophrenia higher levels of insight are associated with increased levels of depression. Although different studies examined this issue, only few took in account potential confounders or factors that could influence this association. In a sample of clinically stable patients with schizophrenia, insight and depression were evaluated using the Scale to assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia. Other rating scales were used to assess the severity of psychotic symptoms, extrapyramidal symptoms, hopelessness, internalized stigma, self-esteem, and service engagement. Regression models were used to estimate the magnitude of the association between insight and depression while accounting for the role of confounders. Putative psychological and sociodemographic factors that could act as mediators and moderators were examined using the PROCESS macro. By accounting for the role of confounding factors, the strength of the association between insight into symptoms and depression increased from 13% to 25% explained covariance. Patients with lower socioeconomic status (F = 8.5, P = .04), more severe illness (F = 4.8, P = .03) and lower levels of service engagement (F = 4.7, P = .03) displayed the strongest association between insight and depression. Lastly, hopelessness, internalized stigma and perceived discrimination acted as significant mediators. The relationship between insight and depression should be considered a well established phenomenon among patients with schizophrenia: it seems stronger than previously reported especially among patients with lower socioeconomic status, severe illness and poor engagement with services. These findings may have relevant implications for the promotion of insight among patients with schizophrenia.

Key words: schizophrenia, depression, insight, stigma, negative symptoms, suicide

Introduction

The expression “insight paradox” has been used to describe the presence of depressive symptoms, or even suicidal ideation, among patients with schizophrenia who have good levels of insight.1,2 The improvement of patients’ insight remains one of the main goals of the clinical management of schizophrenia: attaining insight can lead to improved treatment adherence and better clinical outcomes.3 Nonetheless, should depressive symptoms arise in the process, they may impact negatively on quality of life, prevent from attaining personal goals and increase the risk of suicide4–8: this may leave clinicians in front of a dilemma.

Insight is a complex construct that entails several dimensions, such as the awareness of specific symptoms and the perceived need of treatment. According to contemporary models, insight depends on the interaction of neurocognitive,9 social-cognitive and meta-cognitive abilities,10 which form the basis for the development of a coherent autobiographical narrative.11 Moreover, lack of insight is viewed as a defense mechanism against painful appraisals of the psychotic experience.12 Among patients with schizophrenia, lack of insight has been linked with the severity of psychotic symptoms13 and basic self-disorders.14 As such, it is not surprising that patients may display different degrees of awareness for each domain of insight, and that insight vary along the different phases of the illness.3,15–17 Insight seems amenable to improve by various psychological interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral or metacognitive therapies.18 Such strategies should aim to assist patients developing coherent, adaptive accounts of their mental illness and at the same time avoid the onset of depression. In order to achieve this goal it would be useful to further clarify the nature of the association between insight and depression.5

We recently conducted a meta-analytic review on the relationship between insight and depression in schizophrenia.2 The magnitude of the pooled raw correlation between insight and depression was statistically significant, but surprisingly weak: the different domains of insight did not explain more than 2%–3% of the variance of depression. However, to extend the knowledge on this issue several methodological issues need to be addressed. First, the strength of the association was influenced by the assessment of patients in mixed clinical phases and by inadequate assessment instruments. Both insight and depressive symptoms fluctuate along the illness course, even in chronic patients,17,19,20 therefore to examine clinically stable patients would yield a more accurate view of this phenomenon.2 Second, few studies had taken in account the potential confounding effect of sociodemographic and clinical factors such as age21 and the severity of psychotic symptoms.13 We hypothesized that insight may have a stronger impact on depression if such factors were taken in account. Third, there is limited knowledge on which factors may identify patients who are more amenable to depression when they display better insight (“moderators”). Similarly, few studies have examined the psychological pathways linking insight with depression (“mediators”).22–24

Given these premises, the aim of this study was to examine the association between insight and depression in a sample of clinically stable patients with schizophrenia. Our primary hypothesis was that the severity of psychotic symptoms would confound the association between insight and depression, and that, by ruling out this effect, the strength of the association would increase (suppressor effect). We also aimed at exploring which factors could influence the effect of insight on depression (moderators), hypothesizing that the strength of the association could be increased among patients of older age, male gender, with lower education, greater illness severity, lower socioeconomic status, worse service engagement, smaller social network size, and higher premorbid adjustment. Lastly, we aimed at replicate previous findings indicating that hopelessness, internalized stigma and perceived discrimination mediate the association between insight and depression.

Methods

This study is based on a National Interest Research Project “Depression and Insight in patients with Schizophrenia” conducted in concert with a multicenter study aimed to identify factors affecting real-life functioning of patients with schizophrenia25

Subjects

Recruitment took place in between 2012 and 2014 in the catchment area of the Mental Health Department of Genoa, Italy. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of schizophrenia ascertained through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I-P); age between 18 and 65 and clinical stability, defined as the absence of variation of antipsychotic drug therapy or hospitalization for symptom reacutization in the 3 months before recruitment.25

Exclusion criteria were: neurologic disorders; history of alcohol dependence or substance abuse in the past 6 months; moderate or severe mental retardation; recent history of severe adverse drug reactions, such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome26; inability to provide informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Assessments

Patients underwent a thorough assessment, part of which was described in a recent article.25

Assessment of Insight and Depression.

Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS),27 while insight was assessed using the 20-item version of the Scale to assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD).28 The SUMD yields a multidimensional continuous rating of insight based on the following domains: unawareness of having a mental disorder, unawareness and attribution of symptoms, unawareness of the social consequences of the disorder and of the effects of medications. Each domain is rated for both current and past levels of insight, for a total of 10 domains (table 2). Higher scores correspond to lower levels of insight.29 To explore the relationship between depression and insight of specific symptoms, we also calculated the scores for the unawareness of 3 symptoms dimensions (positive, negative, disorganization) following a procedure used in a recent article.30 Scores for positive symptoms were calculated averaging scores of item 4 and 5; for negative symptoms, items 13–16 and for disorganization, items 6 and 18 of the SUMD.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Domains of Insight and Depressive Symptoms

| Insight Domainsa | Correlation With Depression (r) | P a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental disorder | Unawareness | Current | −.00 | .99 |

| Past | −.08 | .47 | ||

| Achieved effects of medication | Unawareness | Current | −.00 | .97 |

| Past | −.06 | .57 | ||

| Social consequences | Unawareness | Current | −.15 | .20 |

| Past | −.22 | .054 | ||

| Overall symptoms | Unawareness | Current | −.36 | <.001* |

| Past | −.36 | <.001* | ||

| Attribution | Current | .13 | .23 | |

| Past | .13 | .25 | ||

| Symptom domains | ||||

| Positive (item 4, 5) | Unawareness | Current | −.11 | .37 |

| Past | −.11 | .32 | ||

| Attribution | Current | −.08 | .56 | |

| Past | −.13 | .33 | ||

| Negative (item 13–16) | Unawareness | Current | −.39 | <.001* |

| Past | −.32 | .004* | ||

| Attribution | Current | −.04 | .76 | |

| Past | .02 | .87 | ||

| Disorganization (item 6,18) | Unawareness | Current | −.40 | .004* |

| Past | −.23 | .07 | ||

| Attribution | Current | −.15 | .41 | |

| Past | −.08 | .61 | ||

Note: aAlpha level after Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (BH-FDR) correction: P = .011.

*Significant after BH-FDR correction.

Assessment of Other Clinical and Contextual Variables.

The rationale for the choice of factors to be tested as confounders, moderators, mediators is reported in supplementary materials (supplementary table S1). Other assessments included: a detailed schedule for sociodemographic and contextual data; the calculation of socioeconomic status using the Hollingshead index (HI),25 calculated from parents’ educational and work level (higher values corresponding to higher status); Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), with calculation of symptom dimensions scores based on a 5-factor solution (positive, negative, disorganized/concrete, excited and depressed)31; Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS), and its 2 factors (poor emotional expression and avolition, higher scores indicate more severe symptoms)32; St Hans Rating Scale (SHRS, akathisia, parkinsonism and dyskinesia indices, higher scores indicate higher severity) to assess extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS)33 and Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS).

Other assessments included the following: Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale (ISMI, 29 items, total score, higher scores indicate higher levels of internalized stigma), Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination (PDD, 12 items, total score, higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived discrimination), Recovery Style Questionnaire (RSQ, 39 items, sum of subscale scores, higher scores indicate a higher tendency to sealing over), Self-Esteem Rating Scale (SERS, 40 items, total score, higher scores indicate higher self-esteem), Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS, 20 items, total score, higher scores indicate higher levels of hopelessness), Service Engagement Scale (SES, 14 items, total score, higher scores indicate lower levels of internalized stigma), Social Network Questionnaire (SNQ, 15 items, total score, higher scores indicate smaller social network size). Rating tools are referenced in a recent article.25 Assessments were carried out along a 3–5 consecutive days period.

Statistical Analysis

The causal relationship between insight and depression has not been established yet. However, insight was shown to predict the onset of depressive symptoms in a phase of clinical stability.34 Therefore, depression was used as the dependent variable in subsequent analyses.

First, descriptive analyses of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are reported. Second, we computed zero-order correlations between indices of insight (SUMD subscale scores) and severity of depression (CDSS total score). Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction was applied to reduce the risk of type I error. Third, following recent works on the topic,2,10,35 we tested the role of sociodemographic and clinical factors that could confound their association: age, gender, education, length of the illness, severity of symptoms (PANSS symptom dimensions and BNSS factors’ scores), prior alcohol or drug abuse and severity of EPS (SHRS scores). A variable is considered a confounder if it is associated both with the independent and the dependent variable, but is not implicated in their causal pathway.36 Thus, we conducted exploratory analyses using Pearson correlation and t test to identify which candidate confounders were associated both with insight and depression in this sample. To gain an unbiased estimate of the association between insight and depression, confounders were entered in a hierarchical regression model, with depression as the dependent variable and insight as the predictor. We then computed the squared semipartial correlation index of insight and depression, ie, the percentage of the variance of depression explained by insight, above and beyond the variance explained by the confounders.

Fourth, we tested whether a set of sociodemographic and clinical factors worked as moderators and mediators of the association between insight and depression. A moderator is a variable that modifies the form or strength of the relation between an independent and a dependent variable. It may identify subgroups of subjects for which the association is stronger or weaker than for other groups, hence it is critical to generalize research findings to a given population.37 The definition of a moderator is more restrictive than that of a confounder, since it requires a significant interaction effect. Based on previous literature,2,22,23 the following factors were tested as moderators: age, gender, education, severity and length of the illness, extension of the social network (SNQ), socioeconomic status (HI), premorbid adjustment and service engagement (SES scores).

A mediator is a variable that explains, in part or in total, the relationship between 2 other variables, being implicated in their casual pathway. As mediators of the association between insight and depression, we tested internalized stigma (ISMI), perceived discrimination (PDD), and hopelessness (BHS). Moderating and mediating effects were examined using the PROCESS macro (2.12.1 release), a widely used regression-based approach.38 The macro provides with bias-corrected 95% CIs using bootstrap calculation; for mediation analyses, both direct and indirect effect estimation. SPSS 17.0 was used for all analyses.

Results

Sample

We recruited 89 subjects. Table 1 reports the characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

| Sociodemographic | Insight Domains | Mean Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, M% | 69.7 | Unaw. of mental disorder | Current | 1.9±1.0 |

| Mean age | 42.2±10.8 | Past | 2.2±1.1 | |

| Education, y | 12.4±4.2 | Unaw. of effects of medication | Current | 1.7±0.9 |

| Living alone | 14.6 | Past | 2.1±1.1 | |

| Unemployed | 67.4 | Unaw. of social consequences | Current | 2.2±1.2 |

| Hollingshead index score | 21.5±13.6 | Past | 2.3±0.8 | |

| Length of illness, y | 20.5±12.2 | Unaw. of symptoms | Current | 2.7±0.8 |

| Lifetime alcohol abuse | 32.2 | Past | 2.7±0.8 | |

| Lifetime substance abuse | 23.0 | Misattrib. of symptoms | Current | 1.5±0.6 |

| Past | 1.5±0.6 | |||

| Symptoms | Psychological dimensions | |||

| PANSS, total score | 75.9±22.6 | Internalized stigma | ISMI | 38.5±12.0 |

| Positive symptoms | 2.2±1.1 | Perceived discrimination | PDD | 31.8±5.4 |

| Negative symptoms | 3.1±1.1 | Hopelessness | BHS | 8.1±5.0 |

| Disorganization | 2.5±1.2 | Attitude toward self | ATS | 26.6±6.8 |

| Excitement | 1.9±0.8 | Service engagement | SES | 1.12±0.95 |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.7±1.1 | Recovery style | RSQ | 62.1±16.9 |

| CDSS total score | 5.8±4.9 | Premorbid adjustmentb | PA | 0.36±0.18 |

| CDSS score ≥ 7 | 39.3 | |||

| Suicidal ideationa | 9.0 | |||

| BNSS total score | 35.0±15.2 | |||

| Poor emotional expression | 2.4±1.4 | |||

| Avolition | 3.0±1.1 |

Note: ISMI, Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale; PDD, Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination; BHS, Beck Hopelessness Scale; SES, Service Engagement Scale; RSQ, Recovery Style Questionnaire; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; ATS, Attitude Towards Self; PA, Premorbid adjustment.

aItem 8 of the CDSS, rated moderate to severe.

bInfancy.

Association Between Insight and Depression

Among SUMD subscales, only the insight into symptoms (present and past subscales) was significantly associated with depression (r = −.36, P < .001 for both), whereas the dimensions “unawareness of having a mental disorder,” “unawareness of the effects of medications,” “unawareness of the social consequences,” and “symptom misattribution” did not show significant associations (all P > .05, see table 2). The awareness of negative and disorganization symptoms were associated with depression. Given that patients with schizophrenia often show memory deficits,39 we deemed the assessment of current insight to be a more reliable indicator, hence we used the SUMD current unawareness into symptoms subscale for subsequent analyses (henceforth simply termed “insight”).

Confounders of the Association Between Insight and Depression

Among the tested confounders, only those related to symptoms’ severity (PANSS positive symptom dimension and BNSS avolition factor) showed significant associations with both insight and depression. Correlation indices were between small to moderate strength for PANSS positive symptom dimension (r = .25, P = .02 with insight; r = .22, P = .04 with depression) and BNSS avolition (r = .28, P = .01 with insight; r = .25, P = .02 with depression).

Entering these factors in a regression model, there was a significant improvement of the model fit (F change = 11.0, df = 2, P < .001, R 2 change = 19%). Altogether, insight (β = −.53, P < .001), PANSS positive symptom dimension (β = .22, P = .03) and the BNSS avolition factor (β = .36, P < .001) explained 33% of the variance of depression. Based on the semipartial correlation index for insight (r = −.50; R 2 = .25), it could be inferred that the explained covariance strength increased from 13% (zero-order correlation) to 25%, thus indicating suppression by confounders.

The additional material section reports the associations between candidate confounders, moderators, mediators, insight and depression, and complete regression models (supplementary tables S2–S7)

Moderators of the Association Between Insight and Depression

We tested the moderating role of several factors, adjusting the models for the severity of positive and negative symptoms. Age, gender, social network, premorbid adjustment, and length of illness were not significant moderators (all P for interactions > .10). Instead, socioeconomic status was a significant moderator which improved the model (R 2 change = 5.4%, F = 7.5, P = .007, figure 1). For patients with a lower HI (7.7), the relationship between insight and depression was stronger (effect = −4.9, 95% CI: −6.5; −3.4, t = −6.3, P < .001) than for those with an intermediate (HI = 21.5, effect = −3.2, 95% CI: −4.4; −2.1, t = −5.7, P < .001) and a higher socioeconomic status (HI = 35.3, effect = −1.6, 95% CI: −3.2; 0.06, t = −1.9, P = .06).

Fig. 1.

Moderating effect of socioeconomic status on the association between insight and depression. HI, Hollingshead index.

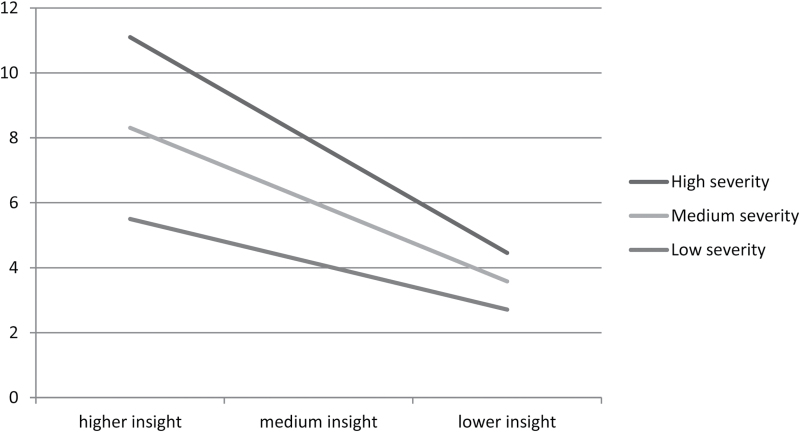

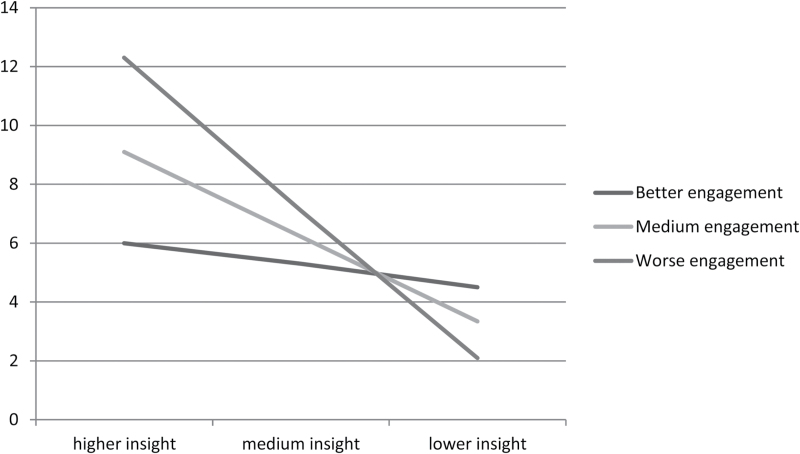

Also, the global severity of the illness (PANSS total score) was a significant moderator (R 2 change = 4%, F = 4.8, P = .03): the higher the severity of the illness, the stronger the association between insight and depression (figure 2). At PANSS total score of 54, which corresponds to a mild clinical picture,40 the effect was −1.7 (95% CI: −3.5; 0.03, t = −1.95, P = .054), at 76 (moderate severity), was −3.0 (95% CI: −4.2; −1.8, t = −5.1, P < .001) and at 98 (severe) it was −4.3 (95% CI: −5.7; −2.8, t = −5.7, P < .001). Lastly, service engagement was a significant moderator (R 2 change = 4%, F = 4.7, P = .03). At lower scores (better service engagement) the effect of insight on depression was nonsignificant (effect = −0.9, 95% CI: −3.6; 1.8, t = −0.67, P = .50), at medium levels, the effect was −3.6 (95% CI: −4.9; −2.3, t = −5.5, P < .001), while at higher scores (worse engagement), it was −6.4 (95% CI: −9.4; −3.4, t = −4.24, P = .001, see figure 3).

Fig. 2.

Moderating effect of illness severity on the association between insight and depression.

Fig. 3.

Moderating effect of service engagement on the association between insight and depression.

Mediators of the Association Between Insight and Depression

Adjusting the model for the severity of positive and negative symptoms, the association between insight and depression was partly mediated by hopelessness (total effect: −3.0, 95% CI: −4.2/ −1.7; direct effect: −2.2, 95% CI: −3.5/ −0.9; indirect effect: −0.8, 95% CI: −1.7/ −0.2), internalized stigma (ISMI; total effect: −3.2, 95% CI: −4.5; −2.0; direct effect: −2.7; 95% CI: −4.0; −1.3; indirect effect: −0.6; 95% CI: −1.2; −0.1) and perceived discrimination (total effect: −3.2, 95% CI: −4.5/ −1.9; direct effect: −2.7; 95% CI: −4.0/ −1.4; indirect effect: −0.5; 95% CI: −1.2/ −0.1).

Discussion

This study aimed to clarify the relationship between insight and depression in patients with schizophrenia, a topic that is characterized by conflicting findings. The association between insight and depression was stronger than previously reported, and was moderated by clinical and contextual factors, such as the severity of the illness, patient socioeconomic status and the level of engagement with mental health services.

Consistent with our previous hypothesis,2 when we ruled out the confounding effect of the severity of positive and negative symptoms, the relationship between insight and depression became stronger. Insight explained 25% of the variance in depression severity, whereas previous estimates indicated values around 3%–4%.2,13 This could be related to methodological and clinical reasons. First, negative symptoms often co-occur, and are difficult to distinguish from depressive symptoms. Even using gold-standard psychometric tools, ratings of depressive and negative symptoms display significant inter-correlations.41 However, negative symptoms are generally associated with reduced insight,42 hence this could entail a statistical suppression effects, such as the one we observed.

Similarly, the severity of positive symptoms is also associated with more severe depression and lower insight.2 Thus, in subgroups of patients suffering from severe positive and/or negative symptoms, it is likely to observe an association between reduced insight and more severe depression, ie, with an opposite direction to the “insight paradox.”

At the clinical level, this phenomenon might be explained by different psychological pathways linking insight, depression and positive symptoms. Literature shows that patients suffering from positive symptoms might become depressed because of subjective appraisals of subordination to auditory hallucinations, or because they deem to be without escape from imaginary persecutory agents.43,44 This pathway might be described as “internal” to the psychotic process, and is consistent with the findings of several studies, conducted in the acute phase of the illness, which found negative associations between insight and depression.2 Whereas, a positive association between good insight and depression (concordant with the “insight paradox”) seem to entail a psychological reaction to the illness, in the presence of good insight, ie, a pathway that is “external” to psychotic symptoms. Consistent with this hypothesis, the relationship between insight and depression is mediated by hopelessness, perceived discrimination and negative appraisals on the illness45,46 and is stronger among studies on clinically stable samples.2

Consistent with previous studies, we did not find significant associations between depression and insight into the need of medication or into the social consequences of the illness.2 In our sample the severity of depression correlated only with ratings of insight into symptoms, whereas in past studies it was also significantly associated with patient awareness of having an illness and symptom attribution. This difference might depend on the fact that previous authors examined younger patients, frequently at their first episode of illness, or recently hospitalized. Among them depression, feelings of shame and embarrassment are often related to the process of coming to terms with the first illness episode or a relapse.47 Whereas, older, stabilized patients are more likely to have gradually accepted the presence of their illness, but the awareness of symptoms may still be an important cause of distress. Consistent with our results, negative symptoms or disorganization may be more difficult to control and become more prominent as the illness becomes chronic.21,46

For the first time, we showed that not only factors related to patients’ psychological status, but also contextual factors changed the impact of insight on depressive symptoms. Worse socioeconomic status amplified the impact of insight on depression. In schizophrenia, lower socioeconomic status is a predictor of worse prognosis.48 However, in our sample the interaction between insight and socioeconomic status was still significant after adjusting for the severity of symptoms, indicating that its role is not due to the severity of the illness. The HI is associated with higher educational attainments,49 better social support,50 self-esteem and more functional coping mechanisms51 but these factors were not significant moderators in our sample. Thus, the effect of SES may depend on other mechanisms. First, higher economic means may increase the access to better healthcare resources, which could in turn improve hope. Second, a higher SES has been associated with optimistic beliefs on the effects of treatment,52,53 and health appraisals were shown to mediate the relationship between insight and depression.46 Third, a higher socioeconomic status might allow more opportunities for leisure activities, thus working as a distraction from the illness.

The association between insight and depression was stronger among those displaying a more severe illness. This could be considered intuitive, yet no one had tested this hypothesis. Subjects with a more severe clinical picture and better levels of insight could be more depressed because they undergo more frequent hospitalizations, be more hopeless,54 or perceive higher discrimination and internalized stigma.55 Similarly, we showed for the first time that service engagement could moderate this association between insight and depression. Individuals with good insight generally display a better engagement to mental health services, yet the quality of the therapeutical relationship can also depend on patients’ appraisals that treatments will not help, lack of shared decision-making and subjective feelings to be too unwell.56 Therefore, patients who disengage from services but display good levels of insight should be closely monitored and screened for depression. Research on moderators such as service engagement may also be useful to clarify why good insight is not consistently found as a risk factor for suicide in schizophrenia, while depression and poor adherence to treatments are.6,57

The findings of the mediating roles of hopelessness, internalized stigma and perceived discrimination are in line with previous literature. These constructs may constitute useful targets for psychological interventions aimed at reducing depression, although in our study their effect was slightly smaller than in previous reports.1,24,54,55 Another study showed that the endorsement of self-stigmatizing views can be particularly detrimental for self-efficacy and prevent from achieving personal goals (the “why try” effect).8 We did not directly assess this construct, but future research based on patient empowerment may help to develop effective interventions that improve insight while maintaining emotional well-being. The recognition and management of depression in schizophrenia is, in fact, still problematic.35,58 Considering the complex, multifaceted nature of insight, interventions that include multiple targets and modalities seem most promising and could indirectly prevent the onset of depressive symptoms in a number of patients.5,18,59

This study is strengthened by a comprehensive, gold-standard assessment and by the systematic assessment of confounders. However, the main limitations are the following. The sample was relatively small and mainly composed of males: this may have prevented from detecting a moderating effect of gender, and may limit the generalizability of findings to females. The cross-sectional design does not allow to draw causal inferences and does not allow to take in account time-dependent changes of insight and depressive symptoms.19,20 However, most changes of insight levels might take place during clinical relapses, thus measuring insight during clinical stability may more closely reflect its trait component.17 Another limitation is we used insight as independent variable and depression as the outcome, although the direction of this relationship is still partly unknown. According to the “depressive realism” hypothesis, depressive symptoms may predispose to develop greater insight.2 Lastly, we did not evaluate patient cognitive and metacognitive abilities, which are likely to play an important role in the relationship between insight and depression.5,10

In conclusion, the association between good insight and depression ought to be considered a well-established clinical phenomenon, rather than a “paradox” (ie, an unexpected occurrence). During the phase of clinically stability, the relationship between insight and depression is stronger than was previously reported, and depends on the appraisal of specific symptoms. Patients with good insight are at higher risk to be depressed if they have lower socioeconomic status, more severe illness and worse service engagement. Structured, multi-component psychotherapy might be useful to contrast the onset of depression, and ultimately promote patients’ well being.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

The study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Education (MIUR) through the 2010–2011 National Interest Project (PRIN) funding program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Costanza Arzani, Benedetta Caprile, Alessandro Corso, Benedetta Olivieri, Sara Patti, and Beatrice Ravizza who kindly helped with data entry. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:192–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belvederi Murri M, Respino M, Innamorati M, et al. Is good insight associated with depression among patients with schizophrenia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2015;162:234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lincoln TM, Lüllmann E, Rief W. Correlates and long-term consequences of poor insight in patients with schizophrenia. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1324–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, et al. Suicide risk in first episode psychosis: a selective review of the current literature. Schizophr Res. 2011;129:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lysaker PH, Vohs J, Hillis JD, et al. Poor insight into schizophrenia: contributing factors, consequences and emerging treatment approaches. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. López-Moríñigo JD, Ramos-Ríos R, David AS, Dutta R. Insight in schizophrenia and risk of suicide: a systematic update. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Melle I, Barrett EA. Insight and suicidal behavior in first-episode schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12:353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corrigan PW, Bink AB, Schmidt A, Jones N, Rüsch N. What is the impact of self-stigma? Loss of self-respect and the “why try” effect. J Ment Health. 2016;25:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shad MU, Keshavan MS, Tamminga CA, Cullum CM, David A. Neurobiological underpinnings of insight deficits in schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lysaker PH, Vohs J, Hasson-Ohayon I, et al. Depression and insight in schizophrenia: comparisons of levels of deficits in social cognition and metacognition and internalized stigma across three profiles. Schizophr Res 2013;148:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lysaker PH, Clements CA, Plascak-Hallberg CD, Knipscheer SJ, Wright DE. Insight and personal narratives of illness in schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2002;65:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGlashan TH, Carpenter WT., Jr Postpsychotic depression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mintz AR, Dobson KS, Romney DM. Insight in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henriksen MG, Parnas J. Self-disorders and schizophrenia: a phenomenological reappraisal of poor insight and noncompliance. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:542–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wiffen BD, Rabinowitz J, Lex A, David AS. Correlates, change and ‘state or trait’ properties of insight in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;122:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilleen J, Greenwood K, David AS. Domains of awareness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koren D, Viksman P, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. The nature and evolution of insight in schizophrenia: a multi-informant longitudinal study of first-episode versus chronic patients. Schizophr Res. 2013;151:245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pijnenborg GH, van Donkersgoed RJ, David AS, Aleman A. Changes in insight during treatment for psychotic disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2013;144:109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parellada M, Boada L, Fraguas D, et al. Trait and state attributes of insight in first episodes of early-onset schizophrenia and other psychoses: a 2-year longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiappelli J, Nugent KL, Thangavelu K, Searcy K, Hong LE. Assessment of trait and state aspects of depression in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:132–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gerretsen P, Plitman E, Rajji TK, Graff-Guerrero A. The effects of aging on insight into illness in schizophrenia: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:1145–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Restifo K, Harkavy-Friedman JM, Shrout PE. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia: a test of the demoralization hypothesis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaiser SL, Snyder JA, Corcoran R, Drake RJ. The relationships among insight, social support, and depression in psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:905–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Staring AB, Van der Gaag M, Van den Berge M, Duivenvoorden HJ, Mulder CL. Stigma moderates the associations of insight with depressed mood, low self-esteem, and low quality of life in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Galderisi S, Rossi A, Rocca P, et al. The influence of illness-related variables, personal resources and context-related factors on real-life functioning of people with schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Belvederi Murri M, Guaglianone A, Bugliani M, et al. Second-generation antipsychotics and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: systematic review and case report analysis. Drugs R D. 2015;15:45–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3:247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, et al. Assessment of insight in psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dumas R, Baumstarck K, Michel P, et al. Systematic review reveals heterogeneity in the use of the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD). Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15:361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freudenreich O, Deckersbach T, Goff DC. Insight into current symptoms of schizophrenia. Association with frontal cortical function and affect. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137:246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mucci A, Galderisi S, Merlotti E, et al. The Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS): independent validation in a large sample of Italian patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gerlach J, Larsen EB. Subjective experience and mental side-effects of antipsychotic treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1999;395:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hwang SS, Chang JS, Lee KY, et al. Causal model of insight and psychopathology based on the PANSS factors: 1-year cross-sectional and longitudinal revalidation. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Siris SG. Depression in schizophrenia: perspective in the era of “Atypical” antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1379–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1:173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mackinnon DP. Integrating Mediators and Moderators in Research Design. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;21:675–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berna F, Potheegadoo J, Aouadi I, et al. A meta-analysis of autobiographical memory studies in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, et al. What does the PANSS mean? Schizophr Res 2005; 79:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lako IM, Bruggeman R, Knegtering H, et al. A systematic review of instruments to measure depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trotman HD, Kirkpatrick B, Compton MT. Impaired insight in patients with newly diagnosed nonaffective psychotic disorders with and without deficit features. Schizophr Res. 2011;126:252–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Upthegrove R, Ross K, Brunet K, McCollum R, Jones L. Depression in first episode psychosis: the role of subordination and shame. Psychiatry Res. 2014;217:177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Birchwood M, Iqbal Z, Upthegrove R. Psychological pathways to depression in schizophrenia: studies in acute psychosis, post psychotic depression and auditory hallucinations. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:202–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cavelti M, Kvrgic S, Beck EM, Rüsch N, Vauth R. Self-stigma and its relationship with insight, demoralization, and clinical outcome among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:468–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cavelti M, Beck EM, Kvrgic S, Kossowsky J, Vauth R. The role of subjective illness beliefs and attitude toward recovery within the relationship of insight and depressive symptoms among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68:462–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sandhu A, Ives J, Birchwood M, Upthegrove R. The subjective experience and phenomenology of depression following first episode psychosis: a qualitative study using photo-elicitation. J Affect Disord. 2013;149:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Samele C, Van OJ, McKenzie K, et al. Does socioeconomic status predict course and outcome in patients with psychosis? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cirino PT, Chin CE, Sevcik RA, et al. Measuring socioeconomic status: reliability and preliminary validity for different approaches. Assessment. 2002;9:145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stringhini S, Berkman L, Dugravot A, et al. Socioeconomic status, structural and functional measures of social support, and mortality: the British Whitehall II Cohort Study, 1985-2009. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1275–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Roohafza H, Sadeghi M, Shirani S, et al. Association of socioeconomic status and life-style factors with coping strategies in Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, Iran. Croat Med J. 2009;50:380–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zuckerman KE, Lindly OJ, Sinche BK, Nicolaidis C. Parent health beliefs, social determinants of health, and child health services utilization among U.S. school-age children with autism. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36:146–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wilkinson AV, Vasudevan V, Honn SE, Spitz MR, Chamberlain RM. Sociodemographic characteristics, health beliefs, and the accuracy of cancer knowledge. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24:58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, Lysaker PH. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1437–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schrank B, Amering M, Hay AG, Weber M, Sibitz I. Insight, positive and negative symptoms, hope, depression and self-stigma: a comprehensive model of mutual influences in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014;23:271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kreyenbuhl J, Nossel IR, Dixon LB. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: a review of the literature. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Deeks JJ. Schizophrenia and suicide: systematic review of risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hausmann A, Fleischhacker WW. Differential diagnosis of depressed mood in patients with schizophrenia: a diagnostic algorithm based on a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hillis JD, Leonhardt BL, Vohs JL, et al. Metacognitive reflective and insight therapy for people in early phase of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71:125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.