Abstract

Background and study aims: Many patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding present with anemia and frequently require red blood cell (RBC) transfusion. A restrictive transfusion strategy and a low hemoglobin (Hb) threshold for transfusion had been shown to produce acceptable outcomes in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. However, most patients are discharged with mild anemia owing to the restricted volume of packed RBCs (pRBCs). We investigated whether discharge Hb influences the outcome in patients with acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

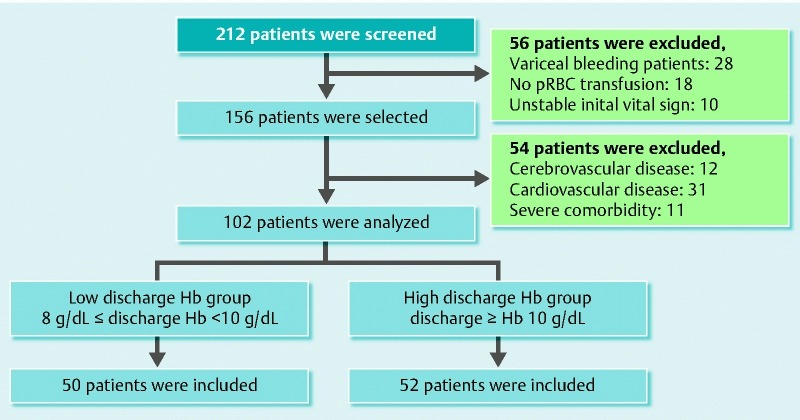

Patients and methods: We retrospectively analyzed patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding who had received pRBCs during hospitalization between January 2012 and January 2014. Patients with variceal bleeding, malignant lesion, stroke, or cardiovascular disease were excluded. We divided the patients into 2 groups, low (8 g/dL ≤ Hb < 10 g/dL) and high (Hb ≥ 10 [g/dL]) discharge Hb, and compared the clinical course and Hb changes between these groups.

Results: A total of 102 patients met the inclusion criteria. Fifty patients were discharged with Hb levels < 10 g/dL, whereas 52 were discharged with Hb levels > 10 g/dL. Patients in the low Hb group had a lower consumption of pRBCs and shorter hospital stay than did those in the high Hb group. The Hb levels were not fully recovered at outpatient follow-up until 7 days after discharge; however, most patients showed Hb recovery at 45 days after discharge. The rate of rebleeding after discharge was not significantly different between the 2 groups.

Conclusions: In patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, a discharge Hb between 8 and 10 g/dL was linked to favorable outcomes on outpatient follow-up. Most patients recovered from anemia without any critical complication within 45 days after discharge.

Introduction

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common reason for emergency hospital admission of patients with a gastrointestinal disorder and the major indication for packed red blood cell (pRBC) transfusion 1 2. Although the hemoglobin (Hb) value can be useful in deciding whether a patient needs a blood transfusion, the reliance on Hb values may result in the underestimation of blood loss. Therefore, the Hb threshold for transfusion after a successful endoscopic hemostasis is controversial. It had been suggested that the therapeutic strategy with conservative transfusion do not affect the mortality risk or length of hospital stay 3.

Furthermore, recently published trials have shown that a restrictive transfusion strategy produces acceptable outcomes in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding 4 5. However, these results may not be generalizable because of the comprehensive inclusion of patients with variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding and those with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Although international consensus suggests the initiation of transfusion when the Hb level decreases to < 8 g/dL in a patient with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding 6, Hb values could be slowly decreased in the early course of acute bleeding. Therefore, many physicians are often concerned about the possibility of a bad prognosis related to an unexpected aggravation of anemia after discharge.

“Discharge Hb,” which means the Hb value within 24 hours before discharge, is a simple but important concept in clinical practice that can be an effective indicator in determining the appropriateness of transfusion 7. Although many patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding are still anemic at discharge, whether discharge Hb affects clinical outcomes at outpatient follow-up has not been investigated. In this study, we investigated the effect of discharge Hb on outcomes in patients with acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Patients and methods

Study design

We carried out a retrospective analysis of all patients who had undergone an urgent endoscopy between January 2012 and January 2014. Medical records, endoscopy reports, and laboratory data were reviewed. The following data on clinical characteristics and prognosis were collected: sex, age, initial vital signs, Hb level, symptoms, total requirement of pRBCs, clinical outcomes, and mortality. The complete Rockall score 8 and Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score 9 were calculated for each patient. A previous study determined that the midpoint of high and low discharge Hb is 10.0 g/dL 7. We therefore divided the patients into two groups on the basis of discharge Hb: low (8 g/dL ≤ Hb < 10 g/dL) and high (Hb ≥ 10 g/dL). Medical records and laboratory data during the outpatient follow-up were also analyzed. We compared the outcomes in terms of pRBC consumption, days of hospitalization, Hb level changes, and patient symptoms. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institution’s human research committee (AN13067-002).

Patients

Patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by benign lesions were screened for this study. Those patients who had received 1 or more units of pRBCs after a successful endoscopic hemostasis were selected. Patients with a history of cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease with or without antiplatelet therapy, unstable initial vital signs (e. g., significant hypovolemic shock and poor mental status), or severe comorbidity were excluded. In addition, patients with insufficient data of blood test were also excluded.

Endoscopic therapy and management

All patients underwent initial endoscopic hemostasis within 12 hours and received intravenous proton pump inhibitors. Hb values were measured every day, and discharge Hb was defined as the last Hb level determined within 24 hours before discharge. The patients were scheduled to visit the outpatient clinic at 7 and 45 days after discharge.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean value ± standard deviation, or as proportions. Chi-square statistics were used to compare the measures, as indicated. The Mann-Whitney U-test for nonnormally distributed data and Student’s t-test for normally distributed data were used to compare the differences between the 2 groups. Data were analyzed with SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 212 patients with a first episode of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to a benign lesion underwent endoscopic hemostasis during the study period. Of these patients, 184 had nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding and 156 had received one or more units of pRBCs during their stay. Fifty-four of them were excluded from study because of a history of cerebrovascular disease (n = 12), cardiovascular disease (n = 31), or severe comorbidity (n = 11). Finally, 102 patients with a successful endoscopic hemostasis fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Assembly of the study population (pRBC, packed red blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Variable | Total | 8 ≤ discharge Hb < 10 (g/dL) | discharge Hb ≥ 10 (g/dL) | P value |

| No. of patients | 102 | 50 | 52 | |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 60.9 ± 16.7 | 61.0 ± 17.5 | 60.8 ± 16.0 | 0.978 |

| Sex (n [%]) | 0.092 | |||

| Male | 80 (78) | 43 (86) | 37 (71) | |

| Female | 22 (22) | 7 (14) | 15 (29) | |

| Initial vital sign (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure | 111.5 ± 22.1 | 112.0 ± 22.4 | 111.0 ± 22.1 | 0.814 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 68.9 ± 14.6 | 69.4 ± 14.6 | 68.5 ± 14.7 | 0.746 |

| Heart rate | 96.7 ± 18.3 | 97.7 ± 20.0 | 95.7 ± 16.7 | 0.586 |

| Presenting symptom (n [%]) | 0.286 | |||

| Melena | 61 (60) | 29 (58) | 32 (61) | |

| Hematemesis | 28 (27) | 15 (30) | 13 (25) | |

| Hematochezia | 7 (7) | 2 (4) | 5 (10) | |

| Others | 6 (6) | 4 (8) | 2 (4) |

Hb, hemoglobin; SD, standard deviation

Diagnosis and endoscopic findings of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Table 2 shows a comparison of endoscopic findings in the 102 patients with acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The complete Rockall score was 4.3 ± 1.2, and the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score was 12.1 ± 2.7. Ninety-one patients had peptic ulcers (duodenal, n = 28; gastric, n = 63), and 11 had Mallory-Weiss tears as a result of vomiting. The most frequent site of bleeding was the body of the stomach (n = 26) in patients with gastric ulcers. We noted no significant difference in the origin, cause, or endoscopic finding of upper gastrointestinal bleeding between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Origin, cause, and endoscopic finding of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Variable | Total | 8 ≤ discharge Hb < 10 (g/dL) | discharge Hb ≥ 10 (g/dL) | P value |

| No. of patients | 102 | 50 | 52 | |

| Source of bleeding (n [%]) | 0.896 | |||

| Gastric ulcer | 63 (62) | 30 (60) | 33 (64) | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 28 (27) | 14 (28) | 14 (27) | |

| Mallory-Weiss tear | 11 (11) | 6 (12) | 5 (9) | |

| Location of bleeding (n [%]) | 0.229 | |||

| EGJ or esophagus | 11 (11) | 6 (12) | 5 (9) | |

| Fundus | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Body | 32 (31) | 18 (36) | 14 (27) | |

| Angle or antrum | 29 (28) | 11 (22) | 18 (35) | |

| Bulb or duodenum | 28 (28) | 14 (28) | 14 (27) | |

| Forrest classification (n [%]) | 0.453 | |||

| Peptic ulcer | 91 | 44 | 47 | |

| Ia | 4 (4) | 2 (5) | 2 (4) | |

| Ib | 22 (24) | 12 (27) | 10 (21) | |

| IIa | 14 (15) | 8 (18) | 6 (13) | |

| IIb | 39 (43) | 14 (32) | 25 (53) | |

| IIc | 12 (13) | 8 (18) | 4 (9) | |

| III | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| UGI bleeding risk score (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Complete Rockall score | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 0.247 |

| Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score | 12.1 ± 2.7 | 12.5 ± 2.1 | 11.7 ± 3.1 | 0.293 |

Hb, hemoglobin; EGJ, esophagogastric junction

Comparison of outcomes between patients with low and high discharge Hb

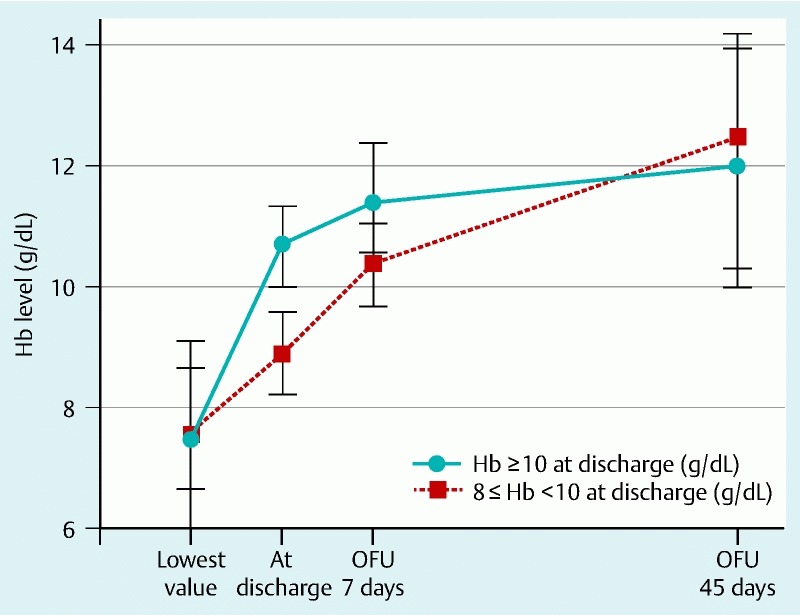

None of the 102 patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding required emergency surgery during admission, and all were discharged without any severe complication. Significant differences in Hb values between the 2 groups were seen at the time of discharge (8.8 ± 0.7 g/dL vs. 10.9 ± 0.9 g/dL; P < 0.001) and at 7 days after discharge (10.4 ± 1.0 g/dL vs. 11.4 ± 1.1 g/dL; P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the Hb level between groups at 45 days after discharge. During outpatient follow-up after discharge, the level of Hb had recovered to 12.2 ± 2.0 g/dL in the low discharge Hb group and 11.9 ± 2.0 g/dL in the high discharge Hb group (Fig. 2). The low discharge Hb group showed a greater increase in Hb during follow-up than did the high discharge Hb group (Table 3). Dizziness due to anemia was significantly more common in the low discharge Hb group. The incidence of other symptoms, such as headache and general weakness, was not significantly different between the 2 groups. There was no significant increase in the risk of rebleeding or in the rate of readmission for any cause between 2 groups. No critical events or mortality occurred during the follow-up period.

Fig. 2 .

Recovery of hemoglobin level from the time of discharge to outpatient follow-up at 7 and 45 days (OFU, outpatient follow-up; Hb, hemoglobin)

Table 3. Transfusion, Hb level change, and outcomes.

| Variable | 8 ≤ discharge Hb < 10 (g/dL) | discharge Hb ≥ 10 (g/dL) | P value |

| Transfusion | |||

| pRBC consumption (pints) (mean ± SD) | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 4.1 ± 1.8 | 0.010 |

| Side effects of transfusion (n [%]) | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | 0.504 |

| Total days of hospitalization | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 5.6 ± 4.2 | 0.636 |

| Hb level (g/dL) (mean ± SD) | |||

| Hb at admission | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 9.1 ± 3.2 | 0.499 |

| Lowest value of Hb | 7.7 ± 1.3 | 8.0 ± 2.3 | 0.146 |

| Hb at discharge | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 10.9 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| 7-day OFU | 10.4 ± 1.0 | 11.4 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| 45-day OFU | 12.2 ± 2.0 | 11.9 ± 2.0 | 0.748 |

| Increase of Hb level at OFU (g/dL) (mean ± SD) | |||

| 7 days | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| 45 days | 3.5 ± 2.0 | 1.0 ± 2.5 | 0.001 |

| Symptoms after discharge (n [%]) | |||

| Headache | 4 (8) | 5 (10) | 0.569 |

| Dizziness | 11 (22) | 6 (12) | 0.004 |

| General weakness | 8 (16) | 6 (12) | 0.195 |

| Rebleeding | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 0.114 |

| Others | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 0.413 |

| Events after discharge (n [%]) | |||

| Readmission for any reason | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 0.909 |

| Mortality due to any cause | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Hb, hemoglobin; pRBC, packed red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; OFU, outpatient follow-up

Discussion

Adequate pRBC transfusion and correction of anemia are important in some severe disease states, and are related to outcome not only during admission but also after discharge 10 11 12. Low Hb is associated with morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease 13. However, it was recently reported that excessive transfusion of pRBCs for the purpose of correcting Hb has no merit, even in critical disease states such as septic shock 14 15. Minimizing unnecessary transfusions lowers costs and the risk of adverse effects. Although transfusion is necessary to correct hypoxemia, hypotension, and tissue hypoperfusion, it also increases the risk of adverse effects such as febrile reaction, acute respiratory distress syndrome, infectious disease transmission, and, rarely, mortality 16 17 18. Moreover, blood transfusion is associated with alterations of the coagulation system 19 20, and is linked to a higher rate of recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding after a successful endoscopic hemostasis 21.

Because changes in the volume status after acute blood loss can make estimating the true Hb level difficult, the minimum acceptable Hb level in patients with long-term upper gastrointestinal bleeding is debated. In previous studies, a restrictive transfusion strategy has been suggested to be effective in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding 4 22. Moreover, early transfusion is known to be associated with an increased risk of rebleeding and mortality 23. However, many previous studies have focused on the Hb threshold for transfusion. Although blood transfusions should be administered to patients with an Hb level of < 7 g/dL 6, there is no international consensus about the minimum acceptable Hb that guarantees patient safety before discharge. Moreover, there is variation in the approach to transfusion for patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding 24.

The results of our study indicate that a transfusion strategy with a minimum acceptable discharge Hb of 8 g/dL is at least as effective as a threshold of 10 g/dL. Although a discharge Hb of 8 g/dL seems too low, it showed no significant difference in the outcomes after discharge. Although the patients in the low discharge Hb group received fewer transfusions of pRBCs, their Hb level during outpatient follow-up recovered more rapidly than did that of patients in the high discharge Hb group. Although increases in Hb level may be influenced by various factors, such as iron status, most patients recovered from anemia at 45 days after discharge. In a previous study, patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding exhibited an overall increase in the quality of life within 3 months of the bleeding episode 25. In our study, a low discharge Hb value between 8 and 10 g/dL was not associated with a significant increase in the incidence of severe complications induced by anemia. Although iron supplementation through drugs could be considered to have an additive effect, it could also lead to confusion between melena and normal dark stool due to the iron agent. In this study, instead of taking oral iron, the patients were advised to consume iron-rich foods before discharge.

Several studies have been conducted on the transfusion strategy in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. However, the relationship between discharge Hb and outcome has not been studied specifically. There has been no research on the clinical course of Hb recovery after upper gastrointestinal bleeding according to different discharge Hb values. In this study, we investigated the influence of discharge Hb at short-term and midterm follow-up after nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. To make the results more reliable, we included only patients who received transfusions because of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Because variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding has a different etiology and clinical course from nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, we excluded patients with these conditions from our study. Two possible limitations of our study are its retrospective nature and the arbitrary definitions of high and low Hb levels. Moreover, the results may have been influenced by the different practices of individual endoscopists, the threshold for pRBC transfusion, comorbidity, and other factors. Despite these limitations, our study has the advantage of being focused on discharge Hb, and thus the results may be useful in establishing a transfusion strategy and treatment plan.

In conclusion, clinically acceptable low Hb levels are not related to the outcome of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Excessive transfusions for higher discharge Hb had no advantage in patients with acute nonvariceal GI bleeding. Even in the presence of a low Hb level at discharge, an acceptable outcome is expected after endoscopic hemostasis for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Recovery of the Hb level after discharge is complete within 45 days.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Basic Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2014R1A2A2A01006131) and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C3477)

Competing interests: None

These authors contributed equally.

References

- 1.van Leerdam M E. Epidemiology of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockall T A, Logan R F, Devlin H B. et al. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom: Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson J L, Hill S, Carless P. et al. Transfusion triggers: a systematic review of the literature. Transfusion Med Rev. 2002;16:187–199. doi: 10.1053/tmrv.2002.33461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A. et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockey D C. To transfuse or not to transfuse in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage? That is the question. Hepatology. 2014;60:422–424. doi: 10.1002/hep.26994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkun A N, Bardou M, Kuipers E J. et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards J, Morrison C, Mohiuddin M. et al. Patient blood transfusion management: discharge hemoglobin level as a surrogate marker for red blood cell utilization appropriateness. Transfusion. 2012;52:2445–2451. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders D S, Carter M J, Goodchap R J. et al. Prospective validation of the Rockall risk scoring system for upper GI hemorrhage in subgroups of patients with varices and peptic ulcers. The Am Journal Gastroenterol. 2002;97:630–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blatchford O, Murray W R, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force . Ferraris V A, Brown J R. et al. 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg 2. 2011;91:944–982. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amsterdam E A, Wenger N K, Brindis R G. et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2354–2394. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diedler J, Sykora M, Hahn P. et al. Low hemoglobin is associated with poor functional outcome after non-traumatic, supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care. 2010;14:63. doi: 10.1186/cc8961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabatine M S, Morrow D A, Giugliano R P. et al. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2005;111:2042–2049. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162477.70955.5F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holst L B, Haase N, Wetterslev J. et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381–1391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson J L, Sieber F, Cook D R. et al. Liberal versus restrictive blood transfusion strategy: 3-year survival and cause of death results from the FOCUS randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlaar A P, Hofstra J J, Determann R M. et al. The incidence, risk factors, and outcome of transfusion-related acute lung injury in a cohort of cardiac surgery patients: a prospective nested case-control study. Blood. 2011;117:4218–4225. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vamvakas E C, Blajchman M A. Transfusion-related mortality: the ongoing risks of allogeneic blood transfusion and the available strategies for their prevention. Blood. 2009;113:3406–3417. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-167643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch C G, Li L, Sessler D I. et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1229–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller R D, Robbins T O, Tong M J. et al. Coagulation defects associated with massive blood transfusions. Ann Surg. 1971;174:794–801. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197111000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed R L II, Ciavarella D, Heimbach D M. et al. Prophylactic platelet administration during massive transfusion: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical study. Ann Surg. 1986;203:40–48. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198601000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginn J L, Ducharme J. Recurrent bleeding in acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: transfusion confusion. Can J Emerg Med. 2001;3:193–198. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500005534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Bao Y X, Bai M. et al. Restrictive vs liberal transfusion for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6919–6927. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hearnshaw S A, Logan R F, Palmer K R. et al. Outcomes following early red blood cell transfusion in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:215–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jairath V, Kahan B C, Logan R F. et al. Red blood cell transfusion practice in patients presenting with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a survey of 815 UK clinicians. Transfusion. 2011;51:1940–1948. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bager P, Dahlerup J F. Patient-reported outcomes after acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:909–916. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.910544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]