Abstract

Domestic violence (DV) is prevalent among women in India and has been associated with poor mental and physical health. We performed a systematic review of 137 quantitative studies published in the prior decade that directly evaluated the DV experiences of Indian women to summarise the breadth of recent work and identify gaps in the literature. Among studies surveying at least two forms of abuse, a median 41% of women reported experiencing DV during their lifetime and 30% in the past year. We noted substantial inter-study variance in DV prevalence estimates, attributable in part to different study populations and settings, but also to a lack of standardisation, validation, and cultural adaptation of DV survey instruments. There was paucity of studies evaluating the DV experiences of women over age 50, residing in live-in relationships, same-sex relationships, tribal villages, and of women from the northern regions of India. Additionally, our review highlighted a gap in research evaluating the impact of DV on physical health. We conclude with a research agenda calling for additional qualitative and longitudinal quantitative studies to explore the DV correlates proposed by this quantitative literature to inform the development of a culturally tailored DV scale and prevention strategies.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, domestic violence, spouse abuse, India, review

Introduction

Domestic violence (DV), defined by the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005 as physical, sexual, verbal, emotional, and economic abuse against women by a partner or family member residing in a joint family, plagues the lives of many women in India. National statistics that utilise a modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) to measure the prevalence of lifetime physical, sexual, and/or emotional DV estimate that 40% of women experience abuse at the hands of a partner (Yoshikawa, Agrawal, Poudel, & Jimba, 2012). Data from a recent systematic review by the World Health Organization (WHO) provides similar regional estimates and suggests that women in South-East Asia (defined as India, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Bangladesh, and Timor-Leste) are at a higher likelihood for experiencing partner abuse during their lifetime than women from Europe, the Western Pacific, and potentially the Americas (WHO, 2013).

Among the different proposed causes for the high DV frequency in India are deep-rooted male patriarchal roles (Visaria, 2000) and long-standing cultural norms that propagate the view of women as subordinates throughout their lifespan (Fernandez, 1997; Gundappa & Rathod, 2012). Even before a child is born, many families have a clear preference for male children, which may result in their preferential care, and worse, sex-selective abortions, female infanticide and abandonment of the girl-child (Gundappa & Rathod, 2012). During childhood, less importance is given to the education of female children; further, early marriage as occurs in 45% of young, married women, according to 2005–2006 National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) data (Raj, Saggurti, Balaiah, & Silverman, 2009), may also heighten susceptibility to DV (Ackerson, Kawachi, Barbeau, & Subramanian, 2008; Raj, Saggurti, Lawrence, Balaiah, & Silverman, 2010; Santhya et al., 2010; Speizer & Pearson, 2011). In reproductive years, mothers pregnant with and/or those who give birth to only female children may be more susceptible to abuse (Mahapatro, Gupta, Gupta, & Kundu, 2011) and financial, medical, and nutritional neglect. Later in life, culturally bred views of dishonour associated with widowhood may also influence susceptibility to DV by other family members (Saravanan, 2000).

In addition to being prevalent in India, DV has also been linked to numerous deleterious health behaviours and poor mental and physical health. These includes tobacco use (Ackerson, Kawachi, Barbeau, & Subramanian, 2007), lack of contraceptive and condom use (Stephenson, Koenig, Acharya, & Roy, 2008), diminished utilisation of health care (Sudha & Morrison, 2011; Sudha, Morrison, & Zhu, 2007), higher frequencies of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and attempted suicide (Chandra, Satyanarayana, & Carey, 2009; Chowdhury, Brahma, Banerjee, & Biswas, 2009; Maselko & Patel, 2008; Shahmanesh, Wayal, Cowan, et al., 2009; Shidhaye & Patel, 2010; Verma et al., 2006), sexually transmitted infections (STI) (Chowdhary & Patel, 2008; Sudha & Morrison, 2011; Weiss et al., 2008), HIV(Gupta et al., 2008; Silverman, Decker, Saggurti, Balaiah, & Raj, 2008), asthma (Subramanian, Ackerson, Subramanyam, & Wright, 2007), anaemia (Ackerson & Subramanian, 2008), and chronic fatigue (Patel et al., 2005). Furthermore, maternal intimate partner violence (IPV) experiences have been associated with more terminated, unintended pregnancies (Begum, Dwivedi, Pandey, & Mittal, 2010; Yoshikawa et al., 2012), less breastfeeding (Shroff et al., 2011), perinatal care (Koski, Stephenson, & Koenig, 2011), and poor child outcomes (Ackerson & Subramanian, 2009). These negative health repercussions and high DV frequency speak to the need for the development of effective DV prevention and management strategies. And, the development of effective DV interventions first requires valid measures of occurrence and an in-depth understanding of its epidemiology.

While many aspects of DV are similar across cultures, recent qualitative studies describe how some aspects of the DV experienced by women in India may be unique. These studies highlight the role of non-partner DV perpetrators for those living in both nuclear and joint-families (Fernandez, 1997; Kaur & Garg, 2010; Raj et al., 2011). (These families are patrilineal where male descendants live with their wives, offspring, parents, and unmarried sisters.) They discuss the high frequency and near normalisation of control, psychological abuse, neglect, and isolation, the occurrence of DV to women at both extremes of age (young and old), dowry harassments, control over reproductive choices and family planning, and demonstrate the use of different tools to inflict abuse (i.e. kerosene burning, stones, and broomsticks as opposed to gun and knife violence more commonly seen in industrialised nations) (Bunting, 2005; Go et al., 2003; Hampton, 2010; Jutla & Heimbach, 2004; Kaur & Garg, 2010; Kermode et al., 2007; Kumar & Kanth, 2004; Peck, 2012; Rastogi & Therly, 2006; Sharma, Harish, Gupta, & Singh, 2005; Stephenson et al., 2008; Wilson-Williams, Stephenson, Juvekar, & Andes, 2008).

This paper presents a systematic review of the quantitative studies conducted over the past decade that estimate and assess DV experienced by women in India, and evaluates their scope and capacity to measure the DV themes highlighted by recent qualitative studies. It aims to examine the distribution of the prevalence estimates provided by the recent literature of DV occurrence in India, improve understanding of the factors that may affect these prevalence estimates, and identify gaps in current studies. This enhanced knowledge will help inform future research including new interventions for the prevention and management of DV in India.

Methods

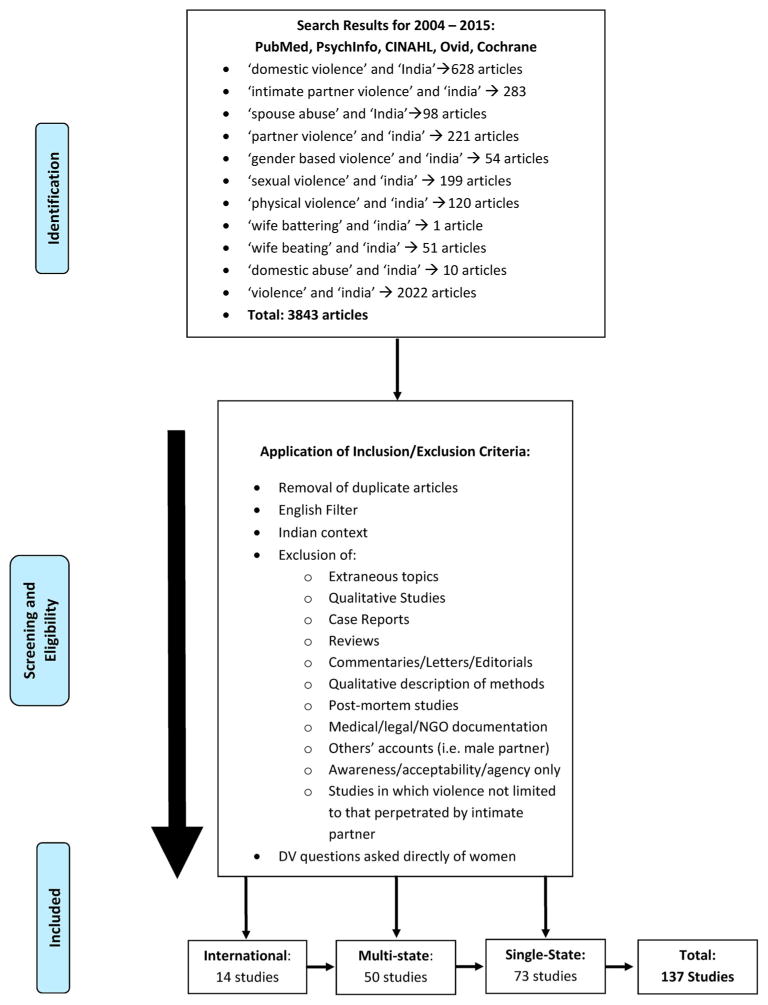

We utilised PubMed, OVID, Cochrane Reviews, PsycINFO, and CINAHL as search engines to identify articles published between 1 April 2004 and 1 January 2015 that focused on the DV experiences of women in India (Figure 1). Our specific search terms included ‘domestic violence’, ‘intimate partner violence’, ‘spouse abuse’, ‘partner violence’, ‘gender-based violence’, ‘sexual violence’, ‘physical violence’, ‘wife battering’, ‘wife beating’, ‘domestic abuse’, ‘violence’, and ‘India’. We first removed duplicate articles and then filtered the articles based on our inclusion criteria: quantitative studies evaluating original data that had been published in English and directly surveyed the DV experiences of women. While we recognise that in cultures where DV is commonplace the reporting of DV perpetration by men may be as high as the frequency of experiencing DV reported by women (Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmed, Jejeebhoy, & Campbell, 2006), we restricted our eligibility criteria to studies directly surveying women about their DV experiences to reduce further inter-study variation and allow for more accurate cross-study comparisons. We excluded reviews, case reports, meta-analyses, and qualitative studies. A single author (ASK or NM) reviewed each individual article to determine whether it met inclusion criteria. If questions arose regarding its inclusion into the review, they were discussed with a second author (SS) until concordance was reached regarding whether or not the paper was to be included.

Figure 1.

Adapted PRISMA Flow Diagram demonstrating study selection methodologies and filter results.

Note: An initial PubMed search of articles published between 1 April 2004 and 1 January 2015 focusing on the DV experiences of women in India is depicted. This figure illustrates the search terms, search engines, applied inclusion and exclusion filters, the process by which articles were chosen to be included in the study, and the results of the selection process.

We collected data from each study regarding study population; study setting; use of a validated scale; forms of, perpetrators of, and time frame during which DV was measured; whether an attempt was made to measure severity of DV; whether potential DV correlates were evaluated; and whether DV prevalence was estimated. We subcategorised the forms of violence into physical, sexual, psychological, control, and neglect based on descriptions of questions provided in the studies. Emotional and verbal forms of abuse were classified as psychological abuse and deprivation was classified as neglect. If the study asked participants about agency or autonomy, this was noted in the summary tables. In publications where information about the DV assessment tool and its validation was not provided, we contacted the authors for more information. If authors reported having conducted formative fieldwork to generate questions, pre-tested the items, and/or conducted some assessment of the measurement tool’s expert or face validity, we reported the validation as ‘limited’. If we did not hear back from the authors, we stated the data were ‘not reported’.

Results

Article yield of systematic search

Our initial search of DV articles published in PubMed, OVID, Cochrane Reviews, PsycINFO, and CINAHL between 1 April 2004 and 1 January 2015 yielded 3843 articles (Figure 1). We identified 628 articles using search terms ‘domestic violence’ and ‘India’, 283 articles using ‘intimate partner violence’ and ‘India’, 98 articles using ‘spouse abuse’ and ‘India’, 221 articles using ‘partner violence and India’, 54 articles using ‘gender-based violence’ and ‘India’, 199 articles using ‘sexual violence’ and ‘India’, 120 articles using ‘physical violence’ and ‘India’, 1 article using ‘wife battering’ and ‘India’, 51 articles using ‘wife beating’ and ‘India’, 10 articles using ‘domestic abuse’ and ‘India’, and 2022 articles using ‘violence’ and ‘India’. Of the 3843 articles, 3705 articles were removed because they (1) were duplicated in the search, (2) focused on extraneous topics, (3) lacked Indian context, (4) were not based on original quantitative data, or (5) were based on study data that were not directly obtained through surveying women about their personal DV experiences. Thus, the selection criteria yielded a total of 137 studies examining the DV experiences of women in India: 14 international studies (see Table 1 in supplementary material), 50 multi-state India studies (see Table 2 in supplementary material), and 73 single-state India studies (see Table 3 in supplementary material).

The scope and breadth of recent studies: study populations

Collectively, the reviewed studies provide information on the DV experienced by young and middle-aged women in traditional heterosexual marriages from both urban and rural environments, joint and nuclear families, across Indian states (Figure 2). Among the studies specifying age limits, the vast majority (88% or 92/104) evaluated DV experienced by women age 15–50, with only 11% (11/104) of studies surveying DV suffered by women above age 50 and 1% (1/104) evaluating DV experienced by young adolescents (wed before age 15). Only one study assessed DV experienced by women in HIV discordant. No studies surveyed DV in non-traditional relationships, such as same-sex relationships or live-in relationships. Less than one-third (29% or 40/137) collected data differentiating DV experienced by women in joint versus nuclear families. Thirty-seven per cent (51/137) evaluated domestic abuse suffered by women living in urban settings, 18% (24/137) in rural, and the remainder (44% or 60/137) in both rural and urban environments. Only one examined DV experienced by women residing in tribes. Twenty-three per cent (32/137) and 3% (4/137) utilised a nationally representative and sub-nationally representative study population, respectively. Southern Indian states were by far the most surveyed in the literature (Maharashtra 66 studies, Tamil Nadu 59 studies, and Karnataka 51 studies) and Northern Indian states the least (Uttaranchal, Sikkim, Punjab, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, and Assam each with 33 studies).

Figure 2.

A summary of the distribution of recent Indian DV literature by region, state, surveyed perpetrator, and family type.

Note: (a) demonstrates the distribution of studies by rural versus urban region, (b) by state, (c) by the perpetrator surveyed, and (d) whether the survey collected data differentiating DV in joint versus nuclear family households.

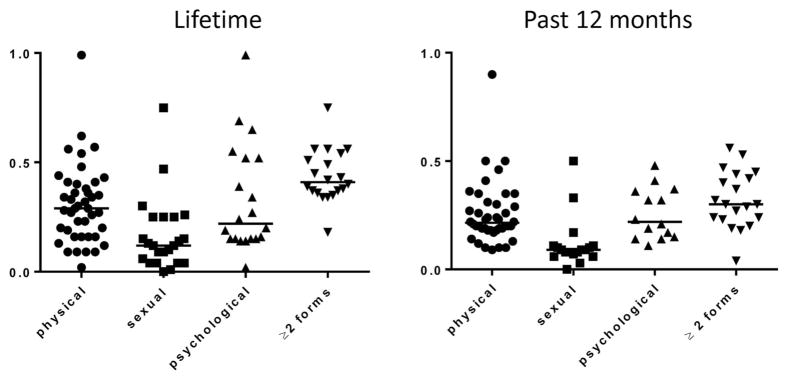

Prevalence of DV in India

Collectively, the reviewed studies demonstrate that DV occurs among Indian women with high frequency but there is substantial variation in the reported prevalence estimates across all forms of DV (Figure 3). For example, the median and range of lifetime estimates of psychological abuse was 22% (range 2–99%), physical abuse was 29% (2–99%), sexual abuse was 12% (0–75%), and multiple forms of DV was 41% (18–75%). The outliers at the upper extremes were contributed by a study of in low-income slum communities with high prevalence of substance abuse(Solomon et al., 2009) and a second study conducted in a tertiary care centre where surveys were self-administered and thus participants may have felt increased comfort in reporting DV(Sharma & Vatsa, 2011). The median and range of past-year estimates of psychological abuse was 22% (11–48%), physical abuse was 22% (9–90%), sexual abuse was 7% (0–50%), and multiple forms of DV was 30% (4–56%). The outlier of 90% for physical abuse was contributed by a study of women whose husbands were alcoholics in treatment (Stanley, 2012). As expected, higher DV prevalence was noted when multiple forms of DV were assessed. Of all forms of DV, physical abuse was measured most frequently, with psychological abuse, sexual abuse, and control or neglect receiving substantially less attention. Further statistical analysis beyond these descriptive statistics was not conducted due to the large inter-study heterogeneity of designs and populations limiting comparability across studies.

Figure 3.

A summary of the lifetime and past 12-month prevalence estimates of the various forms of DV as documented by each individual study.

Note: Circles, squares, upright triangles, and inverted triangles represent prevalence estimates of psychological, physical, sexual, and multiple forms of DV, respectively, as provided by each individual study. While medians and ranges are provided, further analysis was not carried out due to the limited homogeneity between studies impeding accurate comparison.

The scope and breadth of recent studies: study design

The past decade of quantitative India DV research has included a breadth of large regional and international studies as well as smaller scale, single-state studies. However, the capacity to draw causal inferences from this literature has been limited by the nearly exclusive use of cross-sectional design. The country and regional-level studies utilised larger, often nationally or sub-nationally representative samples (average sample size: 25,857 women, range: 111–124,385), to provide inter-country or regional epidemiologic comparisons. The single-state studies tended to use smaller sample sizes (average: 1109 women, range: 30–9639) to provide a more in-depth evaluation of DV experienced in a particular population of women.

The vast majority of all reviewed studies utilised cross-sectional design, with only 12% (17/137) using a prospective design to draw causal inferences. Six of these 13 utilised the NFHS-2 and four-year follow-up data from the rural regions of four states to evaluate the effect of DV on mental health disorders (Shidhaye & Patel, 2010), a woman’s adoption of contraception, occurrence of unwanted pregnancy (Stephenson et al., 2008), uptake of prenatal care (Koski et al., 2011), early childhood mortality (Koenig et al., 2010), functional autonomy and reproduction (Bourey, Stephenson, & Hindin, 2013), and contraceptive adoption (Stephenson, Jadhav, & Hindin, 2013), while one used the data to evaluate the effect of autonomy on experience of physical violence (Nongrum, Thomas, Lionel, & Jacob, 2014; Sabarwal, Santhya, & Jejeebhoy, 2014). Only one study employed a case-control study to evaluate the link between DV and child mortality (Varghese, Prasad, & Jacob, 2013) and another utilised a randomised control design to evaluate the effect of a mixed individual and group women’s behavioural intervention in reducing DV and marital conflict over time (Saggurti et al., 2014). The remainder of prospective studies evaluated the causal association between DV and incident STIs and/or attempted suicide (Chowdhary & Patel, 2008; Maselko & Patel, 2008; Weiss et al., 2008), DV and maternal and neonatal health outcomes (Nongrum et al., 2014), the effect of the type of interviewing (face-to-face versus audio computer-assisted self-interviews) on DV reporting (Rathod, Minnis, Subbiah, & Krishnan, 2011), trends in DV occurrence over time (Simister & Mehta, 2010), and the effect of change in a woman or her spouse’s employment status on her experience of DV (Krishnan et al., 2010).

The scope and breadth of recent studies: DV measures

Only 61% (84/137) of studies reported use of a validated scale or made attempts to validate the instrument they ultimately used. When use of a validated instrument was reported, most (82% or 69/84) had been developed for the cultural context of North America and Europe (i.e. modified CTS, Abuse Assessment Screen, Index of Spouse Abuse, Woman Abuse Screening Tool, Partner Violence Screen, Composite Abuse Scale, and Sexual Experience Scale). In fact, only 15 of the studies reporting use of a validated questionnaire adapted or developed their instrument to the Indian context by surveying themes raised by the prior qualitative literature (i.e. use of belts, sticks, and burning to inflict physical abuse, restricting return to natal family home, not allowing natal family to visit marital home). As expected, these studies reported higher frequencies of DV. In personal communication, some authors who chose not to use validated, widely used DV scales (i.e. CTS) stated they did so because of space limitations and inadequacy of existing tools for measuring DV in the Indian cultural context.

Two-thirds of studies (64% or 87/137) assessed two or fewer forms of DV. Of all forms of DV, physical abuse was evaluated most frequently (96% or 131/137), followed by sexual abuse (58% or 79/137), psychological abuse (44% or 60/137), neglect and control (4% or 7/137). Only 11% (15/137) of studies evaluated DV perpetrated by non-partner family members. For these studies evaluating DV perpetrated by partners and non-partner family members, available estimates of lifetime sexual and psychological abuse were always higher than the median prevalence estimates of reviewed studies; available estimates of lifetime physical abuse were often, but not universally, higher. Only 20% (109/137) attempted to evaluate different levels of DV severity. While many (43% or 59/137) studies evaluated lifetime violence, a considerable number assessed recent DV (42% or 58/137 past-12 month DV, 5% or 7/137 past-6 month DV, 4% or 5/137 past-3 month DV, and 4% or 6/137 the time period of current or research partnerships). Additionally, 10% (14/137) evaluated DV occurrence during pregnancy or the peri-partum period.

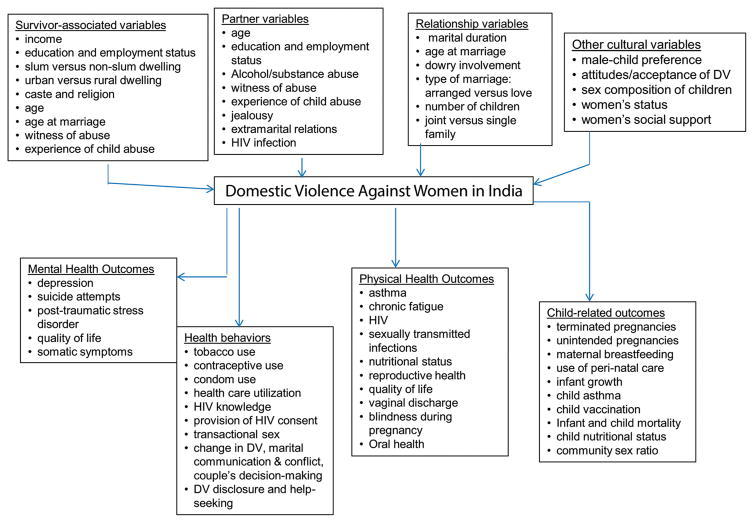

The scope and breadth of recent studies: measured outcomes

Figure 4 provides a framework for synthesising the potential DV correlates measured to date. It demonstrates that the focus of the quantitative literature has largely been on the mental health and gynecologic consequences of DV but has only begun to evaluate repercussions on physical health and health behaviour. Twelve per cent (16/137) of the studies evaluated one or multiple mental health disorder as outcomes of DV, including PTSD, depression, and suicide, but not anxiety. The literature provided a comprehensive evaluation of the association between DV and gynaecologic health including sexual (15% or 21/137) and maternal health (8% or 11/137). However, only six studies were dedicated to evaluating physical health outcomes (oral health, nutrition, chronic fatigue, asthma, direct injury, and blindness during pregnancy). And while 17 studies were dedicated to evaluating the association between DV and uptake of health behaviours, 11 of the 15 were focused on behaviours related to sexual and maternal health. Thus, the association between health behaviours like the woman’s substance abuse and adherence to medical and clinical care remains largely understudied, as does the link between DV and physical health outcomes such as cardiovascular and gastrointestinal disease, chronic pain syndromes (including migraines), and urinary tract infections.

Figure 4.

A framework for conceptualising the reviewed studies.

Note: The proposed framework provides structure for interpreting and synthesising the prior decade’s quantitative research evaluating the domestic violence experienced by women in India.

Discussion

The past 10 years have been an incredible period of growth in DV research in India and South Asia. Our systematic review contributes to the growing body of evidence by providing an important summary of the epidemiologic studies during this critical period and draws attention to the magnitude and severity of the ongoing epidemic in India. Comprehensively, the reviewed literature estimates that 4 in 10 Indian women (when surveyed about multiple forms of abuse) report experiencing DV in their lifetime and 3 in 10 report experiencing DV in the past year. This is concordant with the WHO lifetime estimate of 37.7% (95% CI: 30.9%43.1%) in South-East Asia (defined as India, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Bangladesh, and Timor-Leste) and is higher than the regional estimates provided by the WHO for the Europe, the Western Pacific, and potentially the Americas. In addition to highlighting the high frequency of occurrence, the studies in this review emphasise the toll DV takes on the lives of many Indian women through its impact on mental, physical, sexual, and reproductive health.

Perhaps the most striking finding of our review was the large inter-study variance in DV prevalence estimates (Figure 3). While this variability speaks to the capacity of the India literature to capture the breadth of DV experiences in different populations and settings, it also underscores the need for standardising aspects of study design in the investigator’s control to make effective inter-study and cross-population comparisons. Standardisation of the instruments used to measure DV should be a priority. To optimise the yield of such an instrument in capturing the DV experiences of Indian women, it should build upon currently available, well-validated instruments, but also be culturally tailored. Thus, it should account for the culturally prominent forms of DV identified by the Indian qualitative literature and social media, survey abuse inflicted by non-partner perpetrators, survey multiple forms abuse (i.e. physical, sexual, psychological, and control), and ideally, include a measure of DV severity (i.e. based on frequency of affirmative responses, frequency of abuse, or resultant injury). Our review demonstrates that current studies fall short, with only 61% reporting use of validated questions (rarely developed or adapted to Indian culture), 11% surveying DV perpetrated by non-partner family members, 64% assessing more than two different forms of abuse, and 20% evaluating level of DV severity. Our review also suggests that when questions assessing DV are culturally adapted and validated, evaluate multiple forms of abuse, and survey abusive behaviours by non-partner family members in addition to partners, reporting of DV increases.

While our search yielded many well-designed cross-sectional studies providing insight into the epidemiology of DV in India (i.e. patterns of occurrence, socio-demographic, and health correlates), it also revealed many gaps and thus, a potential research agenda. Future qualitative studies are needed to examine the link between DV and correlates identified by the cross-sectional literature, to inform the development of future prevention strategies, and to enhance delivery of DV supportive services by examining survivor preferences and needs. Additional longitudinal quantitative studies are also needed to better understand predictors of DV and to explore the direction of causality between DV and the physical health associations identified in the reviewed studies. They are also needed to assess the link between DV and other physical health outcomes like injury, cardiovascular disease, irritable bowel syndrome, immune effects, and psychosomatic syndromes as well as non-sexual health behaviours such as substance abuse and medication adherence. This is particularly paramount in India, where physical injury and cardiovascular disease together account for over a quarter of disability-adjusted life years lost (National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, 2005).

Additionally, our review also exposed gaps in the current understanding of DV in some populations and regions of India. For example, most studies focused on women of age 15–50. Only 11 reported on the DV experiences of women over 50, a stage where frailty, financial and physical dependence, and culturally engendered shame and disgrace associated with widowhood may heighten their risk of experiencing DV, neglect, and control by various family members (Solotaroff & Pande, 2014). And, while 43% of Indian women aged 20–24 marry before the age of 18, we encountered few studies evaluating DV experienced by pre-adolescents or young adolescents married as children (UNICEF, 2014). An additional gap is in evaluating the DV experiences of women engaging in live-in relationships as opposed to marital relationships, divorced or widowed women, women involved in same-sex relationships, and in HIV serodiscordant and concordant relationships, settings in which social and family support systems are already weakened (Kohli et al., 2012). Next, beyond the national and multi-state data sets, there is little representation of the northern states of India (i.e. Uttaranchal, Sikkim, Punjab, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, and Assam) and of women residing in tribal villages (Sethuraman, Lansdown, & Sullivan, 2006). The vast cultural, religious, and socio-economic inter-regional differences in India highlight the need for more in-depth study of the DV experiences of women in these areas.

The high prevalence of DV and its association with deleterious behaviours and poor health outcomes further speak to the need for multi-faceted, culturally tailored preventive strategies that target potential victims and perpetrators of violence. The recent Five Year Strategic Plan (2011–2016) released by the Ministry of Women and Child Development discusses a plan to pilot ‘one-stop crisis centres for women’ survivors of violence, which would include medical, legal, law enforcement, counselling, and shelter support for themselves and their children. The significant differences in women’s empowerment and DV experience by region and population within India (Kishor & Gupta, 2004) underscore the need to culturally- and regionally tailor the screening and support services provided at such centres. For example, in resource-limited states where sexual forms of DV predominate, priority should be given to the allocation of health-care providers to evaluate, document, and treat associated injuries and/or transmitted diseases. In settings where financial control and neglect are common, legal, financial, and educational empowerment may need to be given precedence.

Our review is not without limitations. First, our analysis relied solely on data directly provided in the publications. We did not further contact the authors if information was not provided. Second, a single author (ASK or NM) reviewed the individual papers for inclusion into the review, which may have introduced a selection bias. We tried to limit this bias through discussion of the papers in which eligibility was not clear-cut with a second author (SS) until agreement about the inclusion status was reached. Next, we included studies whose main intent was to evaluate the DV experiences of Indian women as well as studies whose main aim may not have been related to DV at all, but included DV as a covariate in the analysis. Thus, many of the studies that solely included DV as a covariate may not have had the intent or resources to fully examine the DV experience. While this may be viewed as a limitation, our goal was not to critically evaluate each individual study, but to comprehensively review the information currently provided in the Indian DV literature. Lastly, inclusion of multiple studies that utilise the same data set (e.g. NFHS) may have skewed the overall median estimate of DV prevalence and the remainder of our analysis. We felt, however, that the substantial differences in DV assessment (e.g. measurement time frames, forms of DV assessed, whether DV severity was assessed, and measured health correlates) between these studies legitimised their need to be included as separate entities in the review.

In conclusion, our literature review underscores the need for further studies within India evaluating the DV experiences of older women, women in same-sex relationships, and live-in relationships, extending the assessment of DV perpetrated by individuals besides intimate partners and spouses, and assessing the multiple forms and levels of abuse. It further stresses the necessity for the development and validation (in multiple regions and study populations within India) of a culturally tailored DV scale and interventions geared towards the prevention and management of DV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center [grant number 1 R25 TW009337-01 K01 TW009664].

Footnotes

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1119293

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Ameeta Kalokhe, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3556-1786

Seema Sahay, http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6064-827X

References

- Ackerson LK, Kawachi I, Barbeau EM, Subramanian SV. Exposure to domestic violence associated with adult smoking in India: A population based study. Tobacco Control. 2007;16(6):378–383. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson LK, Kawachi I, Barbeau EM, Subramanian SV. Effects of individual and proximate educational context on intimate partner violence: A population-based study of women in India. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(3):507–514. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV. Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167(10):1188–1196. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV. Intimate partner violence and death among infants and children in India. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):e878–889. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S, Dwivedi SN, Pandey A, Mittal S. Association between domestic violence and unintended pregnancies in India: Findings from the National Family Health Survey-2 data. National Medical Journal of India. 2010;23(4):198–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourey C, Stephenson R, Hindin MJ. Reproduction, functional autonomy and changing experiences of intimate partner violence within marriage in rural India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2013;39(4):215–226. doi: 10.1363/39215133921513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting A. Stages of development: Marriage of girls and teens as an international human rights issue. Social & Legal Studies. 2005;14(1):17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra PS, Satyanarayana VA, Carey MP. Women reporting intimate partner violence in India: Associations with PTSD and depressive symptoms. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2009;12(4):203–209. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0065-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary N, Patel V. The effect of spousal violence on women’s health: Findings from the Stree Arogya Shodh in Goa, India. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2008;54(4):306–312. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.43514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury AN, Brahma A, Banerjee S, Biswas MK. Pattern of domestic violence amongst non-fatal deliberate self-harm attempters: A study from primary care of West Bengal. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;51(2):96–100. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.49448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M. Domestic violence by extended family members in India: Interplay of gender and generation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12(3):433–455. [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Sethulakshmi CJ, Bentley ME, Sivaram S, Srikrishnan AK, Solomon S, Celentano DD. When HIV-prevention messages and gender norms clash: The impact of domestic violence on women’s HIV risk in slums of Chennai, India. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7(3):263–272. doi: 10.1023/a:1025443719490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundappa A, Rathod PB. Violence against Women in India: Preventive measures. Indian Streams Research Journal. 2012;2(4):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RN, Wyatt GE, Swaminathan S, Rewari BB, Locke TF, Ranganath V, … Liu H. Correlates of relationship, psychological, and sexual behavioral factors for HIV risk among Indian women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(3):256–265. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton T. Child marriage threatens girls’ health. JAMA. 2010;304(5):509–510. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutla RK, Heimbach D. Love burns: An essay about bride burning in India. Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation. 2004;25(2):165–170. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000111929.70876.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R, Garg S. Domestic violence against women: A qualitative study in a rural community. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2010;22(2):242–251. doi: 10.1177/1010539509343949. 1010539509343949 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermode M, Herrman H, Arole R, White J, Premkumar R, Patel V. Empowerment of women and mental health promotion: A qualitative study in rural Maharashtra, India. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S, Gupta K. Women’s empowerment in India and its States. Economic and Political Weekly. 2004;39(7):694–712. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Acharya R, Barrick L, Ahmed S, Hindin M. Domestic violence and early childhood mortality in rural India: Evidence from prospective data. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(3):825–833. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell J. Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(1):132–138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872. AJPH.2004.050872 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli R, Purohit V, Karve L, Bhalerao V, Karvande S, Rangan S, Sahay S. Caring for caregivers of people living with HIV in the family: A response to the HIV pandemic from two urban slum communities in Pune, India. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski AD, Stephenson R, Koenig MR. Physical violence by partner during pregnancy and use of prenatal care in rural India. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2011;29(3):245–254. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i3.7872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Rocca CH, Hubbard AE, Subbiah K, Edmeades J, Padian NS. Do changes in spousal employment status lead to domestic violence? Insights from a prospective study in Bangalore, India. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(1):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Kanth S. Bride burning. Lancet. 2004;364(Suppl 1):s18–s19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17625-3. S0140-6736(04) 17625-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatro M, Gupta RN, Gupta V, Kundu AS. Domestic violence during pregnancy in India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(15):2973–2990. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Patel V. Why women attempt suicide: The role of mental illness and social disadvantage in a community cohort study in India. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2008;62(9):817–822. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. NCMH background papers: Burden of disease in India. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/macrohealth/en/

- Nongrum R, Thomas E, Lionel J, Jacob KS. Domestic violence as a risk factor for maternal depression and neonatal outcomes: A hospital-based cohort study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2014;36(2):179–181. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.130989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Kirkwood BR, Weiss H, Pednekar S, Fernandes J, Pereira B, … Mabey D. Chronic fatigue in developing countries: Population based survey of women in India. British Medical Journal. 2005;330(7501):1190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38442.636181.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck MD. Epidemiology of burns throughout the World. Part II: Intentional burns in adults. Burns. 2012;38(5):630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.12.028. S0305-4179(12)00022-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Sabarwal S, Decker MR, Nair S, Jethva M, Krishnan S, … Silverman JG. Abuse from in-laws during pregnancy and post-partum: Qualitative and quantitative findings from low-income mothers of infants in Mumbai, India. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15(6):700–712. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0651-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: A cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1883–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4. S0140-6736(09)60246-4 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Saggurti N, Lawrence D, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Association between adolescent marriage and marital violence among young adult women in India. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2010;110(1):35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.022. S0020-7292(10)00093-7 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi M, Therly P. Dowry and its link to violence against women in India: Feminist psychological perspectives. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2006;7(1):66–77. doi: 10.1177/1524838005283927. 7/1/66 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod SD, Minnis AM, Subbiah K, Krishnan S. ACASI and face-to-face interviews yield inconsistent estimates of domestic violence among women in India: The Samata health study 2005–2009. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(12):2437–2456. doi: 10.1177/0886260510385125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabarwal S, Santhya KG, Jejeebhoy SJ. Women’s autonomy and experience of physical violence within marriage in rural India: Evidence from a prospective study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29(2):332–347. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saggurti N, Nair S, Silverman JG, Naik DD, Battala M, Dasgupta A, … Raj A. Impact of the RHANI Wives intervention on marital conflict and sexual coercion. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhya KG, Ram U, Acharya R, Jejeebhoy SJ, Ram F, Singh A. Associations between early marriage and young women’s marital and reproductive health outcomes: Evidence from India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;36(3):132–139. doi: 10.1363/ipsrh.36.132.10. 3613210 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan S. Violence against women in India. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman K, Lansdown R, Sullivan K. Women’s empowerment and domestic violence: The role of sociocultural determinants in maternal and child undernutrition in tribal and rural communities in South India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2006 doi: 10.1177/156482650602700204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahmanesh M, Wayal S, Cowan F, Mabey D, Copas A, Patel V. Suicidal behavior among female sex workers in Goa, India: The silent epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(7):1239–1246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma BR, Harish D, Gupta M, Singh VP. Dowry – a deep-rooted cause of violence against women in India. Medicine, Science and the Law. 2005;45(2):161–168. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.45.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma KK, Vatsa M. Domestic violence against nurses by their marital partners: A facility-based study at a tertiary care hospital. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2011;36(3):222–227. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.86525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidhaye R, Patel V. Association of socio-economic, gender and health factors with common mental disorders in women: A population-based study of 5703 married rural women in India. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(6):1510–1521. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq179. dyq179 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff MR, Griffiths PL, Suchindran C, Nagalla B, Vazir S, Bentley ME. Does maternal autonomy influence feeding practices and infant growth in rural India? Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(3):447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among married Indian women. JAMA. 2008;300(6):703–710. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.703. 300/6/703 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simister J, Mehta PS. Gender-based violence in India: Long-term trends. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(9):1594–1611. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S, Subbaraman R, Solomon SS, Srikrishnan AK, Johnson SC, Vasudevan CK, … Celentano DD. Domestic violence and forced sex among the urban poor in South India: Implications for HIV prevention. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(7):753–773. doi: 10.1177/1077801209334602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solotaroff JL, Pande RP. Violence against women and girls: Lessons from South Asia. Washington DC: World Bank., World Bank Group; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Speizer IS, Pearson E. Association between early marriage and intimate partner violence in India: A focus on youth from Bihar and Rajasthan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(10):1963–1981. doi: 10.1177/08862605103729470886260510372947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley S. Intimate partner violence and domestic violence myths: A comparison of women with and without alcoholic husbands (a study from India) Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2012;43(5):647–672. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Jadhav A, Hindin M. Physical domestic violence and subsequent contraceptive adoption among women in rural India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28(5):1020–1039. doi: 10.1177/08862605124593790886260512459379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Koenig MA, Acharya R, Roy TK. Domestic violence, contraceptive use, and unwanted pregnancy in rural India. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(3):177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Ackerson LK, Subramanyam MA, Wright RJ. Domestic violence is associated with adult and childhood asthma prevalence in India. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;36(3):569–579. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudha S, Morrison S. Marital violence and women’s reproductive health care in Uttar Pradesh, India. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudha S, Morrison S, Zhu L. Violence against women, symptom reporting, and treatment for reproductive tract infections in Kerala state, Southern India. Health Care for Women International. 2007;28(3):268–284. doi: 10.1080/07399330601180164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Improving children’s lives, transforming the future: 25 years of child rights in South Asia. 2014 Author. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/publications/index_75712.html.

- Varghese S, Prasad JH, Jacob KS. Domestic violence as a risk factor for infant and child mortality: A community-based case-control study from southern India. National Medical Journal of India. 2013;26(3):142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra V, Khandekar S, Barker G, Fulpagare P, Singh SK. Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14(28):135–143. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visaria L. Violence against women: A field study. Economic & Political Weekly. 2000;35(20):1742–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HA, Patel V, West B, Peeling RW, Kirkwood BR, Mabey D. Spousal sexual violence and poverty are risk factors for sexually transmitted infections in women: A longitudinal study of women in Goa, India. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2008;84(2):133–139. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.026039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Williams L, Stephenson R, Juvekar S, Andes K. Domestic violence and contraceptive use in a rural Indian village. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(10):1181–1198. doi: 10.1177/1077801208323793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa K, Agrawal NR, Poudel KC, Jimba M. A lifetime experience of violence and adverse reproductive outcomes: Findings from population surveys in India. BioScience Trends. 2012;6(3):115–121. doi: 10.5582/bst.2012.v6.3.115. 553 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.