Abstract

Objective

The process of cancer-related breast reconstruction is typically multi-staged and can take months to years to complete, yet few studies have examined patient psychosocial well-being during the reconstruction process. We investigated the effects of reconstruction timing and reconstruction stage on body image and quality of life at specific time points during the breast reconstruction process.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 216 patients were grouped into four reconstructive stages: pre-reconstruction, completed stage 1, completed stage 2, and final stages. Multiple regression analyses examined the roles of reconstruction timing (immediate vs. delayed reconstruction) and reconstruction stage as well as their interaction in predicting body image and quality of life, controlling for patient age, BMI, type of reconstruction, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and major complication(s).

Results

Across the reconstructive stages, differences in patterns of body image were observed with those receiving delayed reconstruction showing significant decrease in body image dissatisfaction compared to those with immediate reconstruction. At pre-reconstruction, patients awaiting delayed reconstruction reported significantly lower social well-being compared to those awaiting immediate reconstruction. Reconstruction stage significantly predicted emotional well-being, with higher emotional well-being observed in those who had commenced reconstruction.

Conclusions

Timing and stage of reconstruction are important to consider when examining psychosocial outcomes of breast cancer patients undergoing reconstruction. Those waiting to initiate delayed reconstruction appear at particular risk for body image, emotional, and social distress. We discuss the implications for delivery of psychosocial treatment to maximize body image and quality of life of patients undergoing cancer-related breast reconstruction.

Keywords: breast cancer, breast reconstruction, body image, quality of life, oncology

Background

In the United States, breast reconstruction is considered part of the standard of care for breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy. Breast reconstruction involves rebuilding of a woman’s breast(s) using autologous tissue, implant(s), or a combination of both. In the case of a unilateral mastectomy, reconstruction includes rebuilding the breast mound, areola, and nipple to match the contralateral breast; in the case of a bilateral mastectomy this would involve recreating both breasts. Restoration of the appearance of the breast via reconstruction is intended to facilitate psychosocial adjustment, including enhancing body image and quality of life [1–4]. However, because the reconstruction process is typically multi-staged and is dependent on many patient- and treatment-related factors, the entire process can take months to years to complete. In order to advance psychosocial care for breast cancer patients undergoing reconstruction, a better understanding of body image and quality of life of patients through the reconstruction process is needed.

Body image reflects a multifaceted concept involving perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and behavior regarding one’s appearance and physical functioning [5,6]. Body image satisfaction, which encompasses feelings of attractiveness and contentment with one’s body, has been shown to be adversely affected due to physical appearance changes from breast cancer [7–9]. Quality of life, another multidimensional construct, comprises the physical, functional, social, and emotional well-being of an individual [10]. Research indicates that for patients with breast cancer, body image satisfaction is positively related to quality of life [11–13]. Body image satisfaction and quality of life of patients undergoing reconstruction surgery can be influenced by a multitude of factors, including patient characteristics (e.g., age, body mass index), adjuvant treatments such as chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and type of reconstruction [14–17].

In the current study, we were interested in evaluating the extent reconstruction timing, reconstruction stage, and their interaction influence body image and quality of life. Reconstruction timing can be thought of as either immediate, where the process commences at the time of mastectomy, or delayed, where the process is initiated months or years after the mastectomy. A number of studies have examined associations between timing of breast reconstruction and psychosocial outcomes [18–20]. However, few studies have defined specific time points of assessments; those that do typically examine psychosocial outcomes at the beginning and the end of the reconstruction process [20–22] or measure time as a function of months or years after the initial surgery [22–24]. Using the time since initial reconstructive surgery can be problematic, as the reconstruction trajectory is often different across patients and contingent upon many factors, such as patient preferences for scheduling the procedure, adjuvant treatments, financial status, and complications. A common conclusion among reviews is that methodological limitations have hindered a comprehensive understanding of patients’ adjustment as they undergo the multi-stage reconstruction process [2,4,25,26].

In this study, we propose to measure the reconstruction process by stage of reconstruction, rather than by time per se, as every patient’s reconstruction timeline is unique. Currently, there is no standardized way of categorizing time points along the breast reconstruction process. We sought to address this issue by proposing a classification scheme that allows grouping of patients into clinically meaningful stages of reconstruction. Our primary aim was to examine the influence of the timing and stage of reconstruction on psychosocial outcomes (i.e., body image dissatisfaction and quality of life) while controlling for patient- and treatment-related factors. Additionally, we were interested in exploring the interaction between timing and stage of reconstruction in predicting the psychosocial outcomes.

Methods

The study sample consisted of adult female patients (N = 216) who had a history of breast cancer and were undergoing treatment at the Center for Reconstructive Surgery at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between 2008 and 2011. This is a cross-section of data from a larger prospective research project. Patients were enrolled at the time of any preoperative visit which included clinic visits prior to placement of an implant, expander, or flap, prior to revision surgery, or prior to nipple reconstruction. Exclusion criteria for the parent study included a history of serious mental illness or cognitive impairment, and inability to read and speak English. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Patients were approached during a pre-operative visit with their reconstructive surgeon. Interested and eligible patients signed an informed consent and completed a self-report questionnaire packet. Participants received a $25 gift card for their participation. Patients’ age, body mass index (BMI), and reconstructive surgery-related information were abstracted from the electronic medical record.

For analysis, patients were classified into one of four reconstructive stage groups based on the type of breast reconstruction procedures they had undergone. Participants were classified as “Pre-reconstruction” if they did not have history of breast cancer-related reconstruction and were about to undergo initial reconstructive surgery. Within this group those scheduled to undergo delayed reconstruction already had mastectomy whereas those scheduled to undergo immediate reconstruction have not undergone mastectomy. Participants were classified as “Completed Stage 1” if they had only undergone initial reconstruction (i.e., placement of autologous flap, tissue expander or implant, or both). Participants were classified as “Completed Stage 2” if they had a tissue expander exchanged for autologous tissue or implant. Of note, only those who had tissue expanders placed in stage 1 would undergo an exchange procedure. Participants were classified as “Final Stages” if they were undergoing surgical revision to improve aesthetic outcomes (e.g., revision of shape, symmetry, nipple reconstruction). The classification scheme was developed with input from two reconstructive surgeons (GPR and MAC) who are experienced in breast reconstructive surgery.

Measures

Body image dissatisfaction

The Body Image Scale [27] is a 10-item measure of body image that was developed for use with cancer patients. Participants rate their dissatisfaction on a 4-point scale (0 = not at all, 3 = very much). The scale has been reported to have high internal consistency (α = .93) and good clinical validity, discriminant validity, and consistency.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured by the 37-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy, Breast Cancer [10,28]. This instrument encompasses four subscales measuring physical, functional, social/family, and emotional well-being. Participants report their responses on a 5-point scale (0 = not all to 4 = very much), and higher subscale scores indicate greater well-being. The measure is widely used, and has strong internal consistency (α = .63–.86), test-retest reliability, and validity.

Analytic Strategies

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Pearson correlations were used to examine associations between study outcomes and age, body mass index (BMI), type of reconstruction, prior chemotherapy, prior radiation therapy, and history of major complication(s). Major complication was defined as of partial or total flap loss, exposure of tissue expander/implant, hematoma requiring drainage, seroma, fat/flap necrosis that required surgery, abdominal hernia/bulge, infection requiring intravenous antibiotics, or development of thromboembolic events. Multiple regression analyses examined the predictive value of reconstruction timing, reconstruction stage, and their interaction on study outcomes controlling for the aforementioned patient- and treatment-related factors. Statistical analyses were conducted using R Version 3.0.2 [29] and SPSS Version 19 [30]. P values < .05 were considered significant.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of our sample. Participants’ mean age was 49 years (SD = 9y). Majority of the participants were Caucasian (87%) and married (71%). With regard to type of reconstruction, 60% underwent implant-based reconstruction, 30 % autologous/flap reconstruction, and 10% a mix of implant and autologous reconstruction. A proportion of the sample had undergone chemotherapy (78%) and radiation therapy (34%). History of a major complication(s) was found in 25% of the sample. Participants about to initiate immediate reconstruction were assessed on average 5 days (SD = 5d, range 1–27d) before mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Participants about to initiate delayed reconstruction were assessed on average 36 months (SD = 45m, range 5–132m) after mastectomy.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, treatment-related factors, and study outcomes (N = 216)

| Variable | n | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 49 (9) | 25–73 | |

| Body mass index | 28 (5) | 17.7–42.3 | |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 187 (87%) | ||

| African American | 14(6%) | ||

| Other | 15(7%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 27 (13%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 163 (75%) | ||

| Not Available | 26 (12%) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 153 (71%) | ||

| Divorced | 30 (14%) | ||

| Widowed | 3(1%) | ||

| Single | 30 (14%) | ||

| History of treatments at the time of assessment | |||

| Chemotherapy | 169 (78%) | ||

| Radiation therapy | 73 (34%) | ||

| Type of reconstructive surgery | |||

| Autologous/flap | 66 (30%) | ||

| Implant | 129 (60%) | ||

| Mixed | 21 (10%) | ||

| Timing of reconstructive surgery | |||

| Immediate | 167 (77%) | ||

| Delayed | 49 (23%) | ||

| Time since mastectomy | |||

| Prior to reconstruction | |||

| Immediate reconstruction | 5 (5) d | ||

| Delayed reconstruction | 36 (45) m | ||

| Completed stage 1 | |||

| Immediate reconstruction | 16 (35) m | ||

| Delayed reconstruction | 37 (44) m | ||

| Completed stage 2 | |||

| Immediate reconstruction | 33 (61) m | ||

| Delayed reconstruction | 60 (32) m | ||

| Final Stages | |||

| Immediate reconstruction | 46 (35) m | ||

| Delayed reconstruction | 46 (13) m | ||

| Stage of reconstructive surgery | |||

| Prior to reconstruction | 86 (40%) | ||

| Completed stage 1 | 86 (40%) | ||

| Completed stage 2 | 25 (11%) | ||

| Final stages | 19(9%) | ||

| History of major complications | 55 (25%) | ||

| Study outcomes | |||

| Body image dissatisfaction | 9.24 (7.43) | 0–30 | |

| Physical well-being | 23.67 (5.55) | 0–28 | |

| Functional well-being | 22.05 (5.90) | 0–28 | |

| Social/family well-being | 23.84 (5.19) | 0–28 | |

| Emotional well-being | 18.87 (4.67) | 0–24 | |

Univariate analysis examined the relationships between the control variables and the outcomes body image dissatisfaction and quality of life. We found the following significant associations: age (r = .24, p < .01), prior chemotherapy (r = .27, p <.01), and prior radiation therapy (r = .20, p <.01) were positively associated with body image dissatisfaction while history of major complication(s) was negatively associated with emotional well-being (r = .14, p = .05).

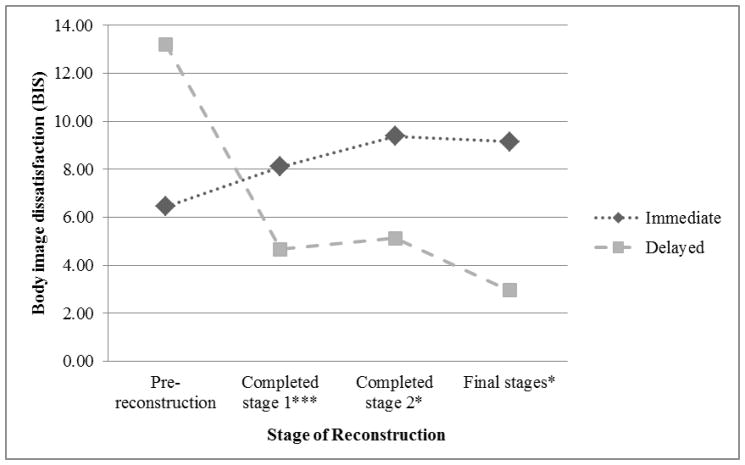

Multivariate analyses then examined the extent reconstruction timing, reconstruction stage, and their interaction predicted body image dissatisfaction controlling for patient- and treatment-related factors. As seen in Table 2, the interaction between reconstruction timing and reconstruction stage was found to significantly predict body image dissatisfaction. Across the reconstruction stages, patients undergoing delayed reconstruction reported significantly worse body image dissatisfaction than those undergoing immediate reconstruction, (β = 6.74, t(170) = 3.76, p < .01). However, the interaction revealed this effect varied strongly as a function of reconstruction stage such that body image dissatisfaction was significantly lower for those who had completed stage 1 (β = −10.19, t(170) = −3.70, p < .01), had completed stage 2 (β = −11.00, t(170) = −2.40, p = .02), or were in the final stages of reconstruction (β = −12.94, t(170) = −2.32, p = .02) when compared to pre-reconstruction. The interaction between reconstruction timing and reconstruction stage is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Timing and stage of reconstruction predicting body image dissatisfaction and quality of life controlling for patient and clinical factors

| Body image dissatisfaction | Quality of life

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical well-being | Functional well-being | Social/family well-being | Emotional well-being | ||

|

| |||||

| β | β | β | β | β | |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Age | −0.21*** | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07* |

| Body mass index | 0.13 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| Reconstruction type | |||||

| Implant-based (reference group) | |||||

| Autologous-based | −0.19 | −0.15 | −0.15 | 0.42 | |

| Mixed type | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | −0.59 | |

| Chemotherapy | 2.83** | −0.87 | 0.40 | 0.40 | −0.85 |

| Radiation therapy | −0.11 | 0.90 | −0.37 | −0.37 | 1.56† |

| Major complication | 0.49 | 0.17 | −0.63 | −0.63 | 0.81 |

| Reconstruction timing | |||||

| Immediate (reference group) | |||||

| Delayed | 6.75*** | −0.48 | −3.19** | −3.19** | −0.75 |

| Reconstruction stage | |||||

| Pre-reconstruction (reference group) | |||||

| Completed stage 1 | 1.66 | 1.09 | −0.57 | −0.57 | 1.94** |

| Completed stage 2 | 2.93 | −0.87 | −1.58 | −1.58 | 1.79† |

| Final stages | 2.70 | −0.85 | −1.75 | −1.75 | 1.84† |

| Timing x Stage interaction | |||||

| Delayed x completed stage 1 | −10.19*** | 1.49 | 3.80* | 3.80* | −0.05 |

| Delayed x completed stage 2 | −11.00* | 4.08 | 3.48 | 3.48 | −1.25 |

| Delayed x final stages | −12.94* | 5.97 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 0.95 |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Figure 1.

The interaction between timing and stages of reconstruction in predicting body image dissatisfaction controlling for patient- and treatment-related factors

*** For patients who underwent delayed reconstruction, body image dissatisfaction was significantly lower for those in the completed stage 1 group as compared to those pre-reconstruction group (p < .01)

* For patients who underwent delayed reconstruction, body image dissatisfaction was significantly lower for those who had completed stage 2 and were in the final stages groups as compared to those in pre-reconstruction group (p < .05)

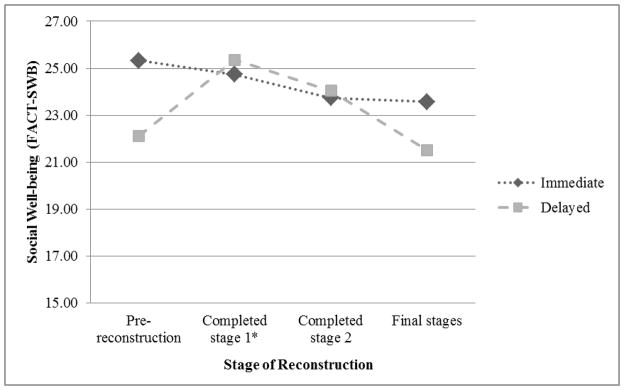

Table 2 also presents the results of regression models examining four quality of life domains as outcomes: physical well-being, functional well-being, social well-being, and emotional well-being. The interaction between reconstruction timing and reconstruction stage significantly predicted social well-being. Across reconstruction stages, patients undergoing delayed reconstruction reported worse social/family well-being (β = −3.19, t(197) = −2.81, p < .01). However, the interaction revealed this effect varied as a function of reconstruction stage such that those who had completed stage 1 reported higher social/family well-being compared to the pre-reconstruction group (β = 3.80, t(197) = 2.18, p =.03). Further, reconstruction stage significantly predicted emotional well-being, independent of reconstruction timing. Compared with those in the pre-reconstruction stage, emotional well-being was significantly higher in the group that had completed stage 1 (β = 1.94, t(197) = 3.08, p < .01) and marginally higher in the group who had completed stage 2 ( β = 1.79, t(197) = 1.88, p =.06) and were in the final stages of reconstruction (β = 1.84, t(197) = 1.74, p =.08).

Discussion

The current study evaluated timing and stage of reconstruction as predictors of body image dissatisfaction and quality of life in patients undergoing cancer-related breast reconstruction. We controlled for patient- and treatment-related factors and found that timing and stage of reconstruction predicted body image dissatisfaction and quality of life beyond age, BMI, reconstruction type, prior treatments received, and history of major complication(s). The interaction between timing and stage of reconstruction significantly predicted body image dissatisfaction and social well-being, while stage of reconstruction significantly predicted emotional well-being.

Body image dissatisfaction was found to be significantly different between groups who had immediate versus delayed reconstruction across reconstructive stages. The most prominent difference was in the pre-reconstruction stage, where those preparing to undergo delayed reconstruction reported significantly higher body image dissatisfaction compared to those preparing to undergo immediate reconstruction. The difference in mean scores in these two groups at pre-reconstruction (refer to Figure 1) are clinically meaningful based on the Body Image Scale cutoff scores of 8–10 previously established in the literature [11,27]. These findings are consistent with previous retrospectively-designed studies that report patients receiving delayed reconstruction recalled higher psychological distress compared to those receiving immediate reconstruction.18,19 As the group waiting to undergo delayed reconstruction consisted of patients who had mastectomy an average of 3 years prior to commencing reconstruction, our findings highlight the need for healthcare providers to be aware of possible prolonged body image distress these patients may experience prior to initiating breast reconstruction. Patients waiting to undergo delayed reconstruction can likely benefit from psychological interventions (e.g., body image therapy) designed to mitigate body image distress following mastectomy. This may be particularly important for patients who may desire immediate reconstruction but are not eligible for the procedure due to treatment plans (e.g., adjuvant radiation therapy) or surgical risk factors such as obesity and smoking status.

Differences were observed in body image dissatisfaction based on the interaction between reconstruction timing and reconstruction stage. For patients who underwent delayed reconstruction, body image dissatisfaction was the highest in the group at pre-reconstruction; other groups demonstrated relatively lower dissatisfaction with their body image. Our findings suggest that for those undergoing delayed reconstruction, commencing the reconstructive process appeared to significantly decrease body image dissatisfaction, consistent with the literature [20, 31–32]. We found a different pattern in patients who sought immediate reconstruction as body image dissatisfaction was the lowest at pre-reconstruction. Although not statistically significant, increased levels of dissatisfaction with body image were found in the immediate reconstruction groups at later stages of reconstruction. It is possible that for patients who opt for immediate reconstruction, higher or unrealistic expectations for cosmetic outcome lead to higher levels of dissatisfaction with body image over the course of reconstruction. This would be consistent with the literature reporting that expectations prior to breast reconstructive surgery are important in predicting patient outcomes [33,34]. If such is the case, patient education to encourage more realistic expectations of breast reconstruction can be valuable to patients and reconstructive surgeons.

We also found the interaction between reconstruction timing and reconstruction stage predicted social well-being. For patients who underwent delayed reconstruction, there was a significant difference in social well-being between those at pre-reconstruction and those who completed stage 1 of reconstruction. We observed that at pre-reconstruction, social well-being is lower for those about to undergo delayed reconstruction compared to those about to undergo immediate reconstruction; however, social well-being was significantly better in the group that has completed stage 1 of reconstruction. Thus, it appears that undergoing delayed reconstruction well after a mastectomy can result in lower levels of perceived social support from one’s spouse, family members, and friends. However, for these patients, perceived support increased once the reconstruction process is initiated. Our finding reflects the literature that suggest social support is greatest closest to the time of a stressful event and typically shifts according to disease progression or patient needs [35,36]. It is entirely possible that women who dealt with the breast cancer diagnosis and mastectomy relatively further back receive less social support at the time of delayed reconstruction. This information is interesting given that patients about to undergo delayed reconstruction endorsed significantly higher body image dissatisfaction. Our findings further highlight the need to provide patients waiting to undergo delayed reconstruction appropriate psychosocial support and care between mastectomy and commencing reconstruction.

Stage of reconstruction emerged as an important predictor of emotional well-being. Patients who had completed stage 1 reported significantly higher emotional well-being, while patients who had completed stage 2 and were in the final stages of reconstruction reported marginally higher emotional well-being compared with those at the pre-reconstruction stage. Whether the reconstruction was immediate or delayed did not predict emotional well-being. Taken together, our findings suggest that commencing the reconstruction process, regardless of whether it is immediate or delayed, provides significant enhancement to the emotional well-being of patients who seek breast reconstruction. Such findings support the purpose of breast reconstruction surgery—to facilitate patients’ psychosocial adjustment and increase their quality of life [2,3]. Given there were differences in body image dissatisfaction between those seeking delayed versus immediate reconstruction, we were somewhat surprised that we did not find significant differences in emotional well-being between these two groups. Our study ample was recruited in a reconstructive surgery clinic and consisted of patients who desired reconstruction and were planning for reconstruction, suggesting a selection bias may have existed. We may have observed greater differences in emotional well-being between those seeking delayed reconstruction and opting for immediate reconstruction if the former group had included women who desired but were not eligible for breast reconstruction.

It is worth mentioning that timing and stage of reconstruction did not significantly predict physical and functional well-being. It is possible that after controlling for patient characteristics (i.e., age, BMI) and treatment-related factors (i.e., reconstruction type, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and major complications), reconstruction timing and stage no longer significantly predicted patients’ physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue, pain) and ability to engage in daily tasks. Interestingly, reconstruction type was not associated with body image or quality of life, suggesting that whether a patient had received an implant-based, autologous, or mixed-type reconstruction had no significant effect on their body image or quality of life. Younger age, prior chemotherapy, and prior radiation therapy were significantly associated with higher body image dissatisfaction in univariate analysis. However, only age and chemotherapy continued to be a significant predictor of body image dissatisfaction in the multivariate model. History of major complication(s) was significantly associated with emotional well-being in univariate analyses consistent with the literature that report history of complication(s) to be associated with patient-reported aesthetic outcomes and decisional regret [37–38]. However, history of major complication(s) was no longer a significant predictor in our multivariate model. The disparity in findings may be due to the difference in outcomes measured. It is also probable that major complication(s) is associated with emotional well-being, but is not as important in predicting emotional well-being when compared to other factors such as reconstruction stage and patient age.

Several limitations of the study are worth discussing. The design of the study was cross-sectional and thus comparisons were made across groups without being able to account for intra-individual differences. However, we believe our findings serve as a foundation to be built upon in future prospectively designed studies that investigate the changing nature of body image and quality of life through the reconstruction process and beyond. The reconstructive stages categories were created as a way to conceptually classify the reconstructive process into stages by our experienced surgeons. Although further validation is necessary before it is used as a standard, we believe such a scheme allowed us to explore how stages in the reconstructive process influence psychosocial well-being of patients.

In summary, we found that the timing and stage of reconstruction have an important influence on the body image and quality of life of patients undergoing breast reconstruction. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined patients during the interim stage of breast reconstruction in this manner. The results that we report— the differences in body image distress across reconstruction timing and stages, the differences in social support across reconstruction timing and stage, and the increase in emotional well-being once the reconstruction process has begun —are congruent with our general clinical impressions. We provide preliminary evidence that examining patients based on reconstructive stage, rather than time since surgery, can better facilitate our understanding of patient psychosocial adjustment. This can be clinically useful to identify patients in need of support as they prepare for and undergo breast reconstruction. Our findings also have implications for developing targeted interventions to improve their body image and quality of life.

Figure 2.

The interaction between timing and stages of reconstruction in predicting social well-being controlling for patient- and treatment-related factors

* For patients who underwent delayed reconstruction, social well-being was significantly different between those in the pre-reconstruction group and completed stage 1 group (p < .05)

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This research was supported in part by the American Cancer Society (ACS RSGPB-09-157-01-CPPB), National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA143190), National Cancer Institute (CA016672), and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (P30-CA016672).

References

- 1.Harcourt D, Rumsey N. Psychological aspects of breast reconstruction: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:477–487. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potter S, Winters Z. Does breast reconstruction improve quality of life for women facing mastectomy? A systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1181. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dabeer M, Fingeret MC, Merchant F, et al. A research agenda for appearance changes due to breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer: Basic Clin Res. 2008;2:1–3. doi: 10.4137/bcbcr.s784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Souza N, Darmanin G, Fedorowicz Z. Immediate versus delayed reconstruction following surgery for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:7. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008674.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Epner DE. Managing body image difficulties of adult cancer patients: Lessons from available research. Cancer. 2014;120:633–641. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cash TF. Cognitive-behavioral perspectives on body image. In: Cash TF, Pruzinsky T, editors. Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. New York: Guilford; 2002. pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carver CS, Pozo-Kaderman C, Price AA, et al. Concern about aspects of body image and adjustment to early stage breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:168–174. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopwood P. The assessment of body image in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29:276–281. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90193-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White CA. Body image dimensions and cancer: A heuristic cognitive behavioural model. Psychooncology. 2000;9:183–192. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<183::aid-pon446>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falk Dahl CA, Reinertsen KV, Nesvold IL, et al. A study of body image in long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2010;116:3549–3557. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3322–3330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimozuma K, Ganz PA, Petersen L, et al. Quality of life in the first year after breast cancer surgery: Rehabilitation needs and patterns of recovery. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;56:45–57. doi: 10.1023/a:1006214830854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fingeret MC, Nipomnick SW, Crosby MA, et al. Developing a theoretical framework to illustrate associations among patient satisfaction, body image and quality of life for women undergoing breast reconstruction. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marín-Gutzke M, Sánchez-Olaso A. Reconstructive surgery in young women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang DW, Reece GP, Wang B, et al. Effect of smoking on complications in patients undergoing free TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2374–2380. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran NV, Evans GR, Kroll SS. Postoperative adjuvant irradiation: Effects on tranverse rectus abdominis muscle flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:313–317. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200008000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Ghazal S, Sully L, Fallowfield L, et al. The psychological impact of immediate rather than delayed breast reconstruction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:17–19. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wellisch DK, Schain WS, Noone RB, et al. Psychosocial correlates of immediate versus delayed reconstruction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:713–718. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198511000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth RS, Lowery JC, Davis J, et al. Quality of life and affective distress in women seeking immediate versus delayed breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:993–1002. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000178395.19992.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosson GD, Shridharani SM, Magarakis M, et al. Quality of life before reconstructive breast surgery: A preoperative comparison of patients with immediate, delayed, and major revision reconstruction. Microsurg. 2013;33:253–258. doi: 10.1002/micr.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalfe KA, Semple J, Quan M-L, et al. Changes in psychosocial functioning 1 year after mastectomy alone, delayed breast reconstruction, or immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:233–241. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harcourt DM, Rumsey NJ, Ambler NR, et al. The psychological effect of mastectomy with or without breast reconstruction: A prospective, multicenter study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1060–1068. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000046249.33122.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Ritz LJ, et al. Quality of life after breast carcinoma surgery. Cancer. 2001;91:1238–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winters ZE, Benson JR, Pusic AL. A systematic review of the clinical evidence to guide treatment recommendations in breast reconstruction based on patient-reported outcome measures and health-related quality of life. Ann Surg. 2010;252:929–942. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e623db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang S-Y, Shu B-C, Chang Y-J. The effect of breast reconstruction surgery on body image among women after mastectomy: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, et al. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SPSS for Windows. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2010. Version 19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veiga DF, Neto MS, Ferreira LM, et al. Quality of life outcomes after pedicled TRAM flap delayed breast reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkins EG, Cederna PS, Lowery JC, et al. Prospective analysis of psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: One-year postoperative results from the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcome Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1014–1025. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200010000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snell L, McCarthy C, Klassen A, et al. Clarifying the expectations of patients undergoing implant breast reconstruction: A qualitative study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1825–1830. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f44580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong T, Hu J, Bagher, et al. Decision regret following breast reconstruction: The role of self-efficacy and satisfaction with information in the preoperative period. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:724e–734e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a3bf5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nausheen B, Gidron Y, Peveler R, et al. Social support and cancer progression: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chantler M, Podbilewicz-Schuller Y, Mortimer J. Change in need for psychosocial support for women with early stage breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;23:65–77. doi: 10.1300/j077v23n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong T, Bagher S, Jindal K, et al. The influence of dispositional optimism on decision regret to undergo major breast reconstructive surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:526–530. doi: 10.1002/jso.23437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colakoglu S, Khansa I, Curtis MS, et al. Impact of complications on patient satisfaction in breast reconstruction. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1428–1436. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318208d0d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]