Abstract

Aims

The anti-hyperglycemic agent linagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, has been shown to reduce inflammation and improve endothelial cell function. In this study, we hypothesized that DPP-IV inhibition with linagliptin would improve impaired cerebral blood flow in diabetic rats through improved insulin-induced cerebrovascular relaxation and reversal of pathological cerebrovascular remodeling that subsequently leads to improvement of cognitive function.

Main Methods

Male type-2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) and nondiabetic Wistar rats were treated with linagliptin, and ET-1 plasma levels and dose response curves to ET-1 (0.1–100 nM) in basilar arteries were assessed. The impact of TLR2 antagonism on ET-1 mediated basilar contraction and endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine (ACh, 1 nM–1 M) in diabetic GK rats was examined with antibody directed against the TLR2 receptor (Santa Cruz, 5 μg/mL). The expression of TLR2 in middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) from treated rats and in brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) treated with 100nM linagliptin was assessed.

Key Findings

Linagliptin lowered plasma ET-1 levels in diabetes, and reduced ET-1-induced vascular contraction. TLR2 antagonism in diabetic basilar arteries reduced ET-1-mediated cerebrovascular dysfunction and improved endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Linagliptin treatment in the BMVEC was able to reduce TLR2 expression in cells from both diabetic and nondiabetic rats.

Conclusions

These results suggest that inhibition of DPPIV using linagliptin improves the ET-1-mediated cerebrovascular dysfunction observed in diabetes through a reduction in ET-1 plasma levels and reduced cerebrovascular hyperreactivity. This effect is potentially a result of linagliptin causing a decrease in endothelial TLR2 expression and a subsequent increase in NO bioavailability.

Keywords: Diabetes, Endothelin, Linagliptin, TLR2, Cerebrovasculature

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases in the United States, with approximately 9% of the population (29 million) suffering from the disorder. The vast majority (upwards of 95%) of these patients are type 2 diabetics1, indicating a pressing need for the development of new and improved therapeutic options for treating this disease. Diabetes is well known to cause both macrovascular and microvascular complications, which can lead to the development of pathologies such as stroke and cognitive impairment2,3. The cerebrovasculature is comprised of large extracranial and intracranial arteries (e.g. the basilar artery), and these vessels contribute to the development of vascular resistance and regulation of cerebral blood flow4,5. It has been shown that a reduction in cerebral blood flow as a result of vascular dysfunction and damage can lead to the development of cognitive impairment6. While our current understanding of the complex mechanisms involving the development of vascular cognitive impairment in diabetes remains limited, there is a clear need for new therapeutic approaches to combat this process.

ET-1 is predominately generated by vascular endothelial cells, and acts through either the ETA receptor or ETB receptor to exert its effect on vascular function. The ETA receptor on smooth muscle cells is thought to be primarily responsible for the vasoconstrictive properties of ET-1, while the ETB receptor on endothelial cells leads to the release of nitric oxide and subsequent vasodilation7–9. In diabetes, circulating plasma levels of ET-1 are elevated in both human patients as well as in the Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat, a lean type 2 diabetes animal model10–12. We reported that glycemic control with metformin10 attenuated this increase in ET-1 levels in the GK rat. This was associated with improvement of cerebrovascular dysfunction characterized by hyper-reactivity to ET-1, and impaired endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation13,14. However, mechanisms contributing to cerebrovascular dysfunction in diabetes are multifactorial and not fully understood. The role of inflammation in diabetes and its associated complications is an increasingly studied area. Recent studies have shown that Toll-like receptors (TLRs), in particular TLR2 and TLR4, are involved in the development of diabetic microvascular disease15,16. TLR2 has been implicated in vascular inflammation leading to decreased endothelial function17,18 as well as playing a crucial role in the development of diabetic nephropathy19. However, the role of TLR2 in the development of diabetic cerebrovascular dysfunction and possible interaction with the ET system remains uncharacterized.

A relatively new treatment for diabetic patients are the DPPIV inhibitors, which are oral hypoglycemic agents. DPPIV is a widely expressed peptidase that exists both in a transmembrane and a catalytically active soluble form20. Many substrates of DPPIV have been identified, the most well categorized of which are the incretins GLP-1 and GIP-1. DPPIV inhibitors such as linagliptin and sitagliptin prevent DPPIV induced cleavage of GLP-1 and GIP-1, which potentiates their insulin secreting and glucagon lowering effects. There has been recent evidence suggesting that inhibition of DPPIV may have beneficial pleotropic effects aside from their anti-hyperglycemic properties. Shah et al.21 have reported inhibition of alogliptin modulates vascular tone independent of GLP-1 through nitric oxide (NO) and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) dependent pathways. Linagliptin, one of the more potent DPPIV inhibitors, has been shown to improve vascular function through anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory effects independent of its glucose-lowering properties22. This anti-inflammatory effect of DPPIV inhibitors was also demonstrated in mononuclear cells from type 2 diabetic patients treated with sitagliptin, where mRNA expression of TLR2 was reduced both after a single dose and twelve weeks of treatment23. However, the effect of DPPIV inhibition with linagliptin on ET-mediated cerebrovascular dysfunction and endothelial TLR2 expression has not been examined. In the current study, we hypothesized that linagliptin would restore cerebrovascular function through glucose dependent and independent effects via regulation of the ET-1 and TLR2 expression.

Methods

Animals

All experiments were performed using male Wistar rats from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and male diabetic GK rats (Taconic; Hudson, NY). The animals were housed at the Georgia Regents University animal care facility that is approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Animals were fed standard rat chow and tap water ad libitum. Body weights and blood glucose measurements were taken biweekly. Blood glucose (BG) measurements were taken from tail vein samples using a commercially available glucometer (Freestyle, Abbott Diabetes Care, Inc.; Alameda, CA).

Animal treatments

Linagliptin treatment in both nondiabetic and diabetic rats was started at 24 weeks of age and was given for a period of 4 weeks. As other studies have reported, and on suggestion from the supplier of linagliptin (Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.), we initially began treating the rats with 83 mg of linagliptin/kg of chow. This treatment corresponds to plasma levels of ~100 nM and a 5 mg/kg oral dose. Upon monitoring of blood glucose levels for a period of one week, we did not notice any blood glucose reduction in the treated rats, and subsequently doubled the dose of linagliptin to 166 mg/kg of chow. Still no effect on blood glucose levels was noted, which was a similar to findings published by others24,25. Drug delivery was confirmed using a DPPIV activity assay that showed a reduction in plasma DPPIV activity levels in the treated groups. Inclusion in the diabetic groups was based on the presence of hyperglycemia, which was defined as fasting blood glucose levels above 180 mg/dL.

For the vascular function experiments in diabetic GK rats examining the impact of TLR2 antagonism on basilar artery function, male rats aged 12 weeks were utilized. We have previously shown that GK rats in this age range (10–12 weeks) exhibit cerebrovascular dysfunction characterized by hyperreactivity to ET-1 (13, 14).

Endothelin-1 chemiluminescent immunoassay

At the end of the treatment duration, blood was collected via cardiac puncture under anesthesia with ketamine/xylazine (80mg/kg:10 mg/kg IP). ET-1 levels in the plasma of both linagliptin treated and untreated Wistar and GK rats were assessed using the QuantiGlo Endothelin-1 ELISA kit (Bioteck, R&D, USA) according manufacturer’s protocol and reported as total ET-1 levels.

Determination of vascular function

Animals were anesthetized and decapitated. The brain was quickly excised for isolation of basilar arteries, and vessels were cut in to 2mm segments. Isometric tension exerted by the vessels was recorded via a force transducer using the wire-myograph technique (Model 610M, Danish Myo Technologies, Denmark). The myograph chambers were filled with Kreb’s buffer (118.3mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.5 mMCaCl2, and 11.1 mM dextrose), gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and maintained at 37 C. Vessel segments were mounted in the chamber using 40-μm-thin wires and adjusted to a baseline tension (0.5 g). After stabilization, the vessels were challenged with 120 mM KCl, washed and allowed to equilibrate for 30 minutes, and endothelial integrity was assessed by pre-contraction with serotonin (1 μM) and subsequent addition of acetylcholine (ACh, 1 μM). Cumulative dose-response curves to 0.1–100 nM ET-1 were performed and the force generated was expressed as percent change from baseline. Maximum contractile response and area under the curve (used as an index of total contraction) were assessed, as well as sensitivity to ET-1 as measured by EC50. In the experiments examining the impact of TLR2 antagonism on ET-1 mediated basilar contraction in diabetic GK rats, 30-min pre- incubation with antibody directed against the TLR2 receptor (Santa Cruz, 5 μg/mL) was used.

Endothelium-dependent relaxation to 1 nM – 50 μM ACh was assessed after vessels were constricted to 60% of the baseline tension with 5-HT either alone or with a 30-min pre- incubation with antibody directed against the TLR2 receptor (Santa Cruz, 5 μg/mL). Sensitivity (median effective concentration [EC50]) and total relaxation response (Area Under the Curve) were calculated from the respective dose-response equations

Cell culture

Brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVECs) from 10–12 week old Wistar or GK rats were isolated as described previously26,27. Cells were grown in MCDB131 medium (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, catalog: 10372-019). Cells were switched to serum-free medium 6 hrs. before treatment with linagliptin 100 nM for 24 hours. Experiments were performed using cells between passages 3 and 5.

Western blots

Cells were washed with PBS following treatment and harvested in ice cold Tris/HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) containing EDTA (0.1 mM), EGTA (0.1 mM), and 2-mercaptoethanol (12mM), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (0.2M), Sodium Orthovanadate (0.1M), Sodium fluoride (1M), protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100, Sigma Aldrich, catalog: P8340), phosphate inhibitor cocktail 2 (1:100, Sigma Aldrich, catalog: P5726), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 3 (1:100, Sigma Aldrich, catalog: P0044). Samples were sonicated for 3 bursts of 10 seconds, and 4X LDS sample buffer was added. Equal protein loads (20 μg) of cellular lysate were boiled and separated on a 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis. Rat specific anti-TLR2 (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, catalog: ab108998) and anti-β-actin antibodies (1:20,000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, catalog: A3864) were used. Primary antibodies were detected using a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody (TLR2: 1:10,000 anti-rabbit, Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, catalog: 7074; β-actin: 1:40,000 anti-mouse, CalBioChem, Billerica, MA, catalog:401215) and enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Relative optical densities of immunoreactivity were determined by ImageJ software (U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) fixed in formalin that were maintained at a constant 60 mmHg intraluminal pressure in calcium-free Krebs-HEPES buffer for 30 minutes and then frozen immediately. Sections were blocked in 10% normal serum for 30 minutes, and primary rabbit anti-TLR2 polyclonal antibody (Bioss, Woburn, MA, catalog: bs-1019R) at 1:200 dilution was incubated in 4°C overnight. Biotinylated rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA, catalog: BA-5000) was incubated at 1:200 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Biotinylated peroxidase was added to each section and incubated for 30 min at room temperature, then washed 2 times with PBS for 5 min each. Sections were incubated for 5 minutes each with Vector Lab DAB kit.

Statistical analysis

Results are given as means ± SEM. For ET-1 plasma levels, EMax, EC50, Rmax, and relative optical density measurements, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done to analyze disease and treatment effects with a post-hoc Tukey test. GraphPad Prism 6.0 was used for all statistical tests performed.

Results

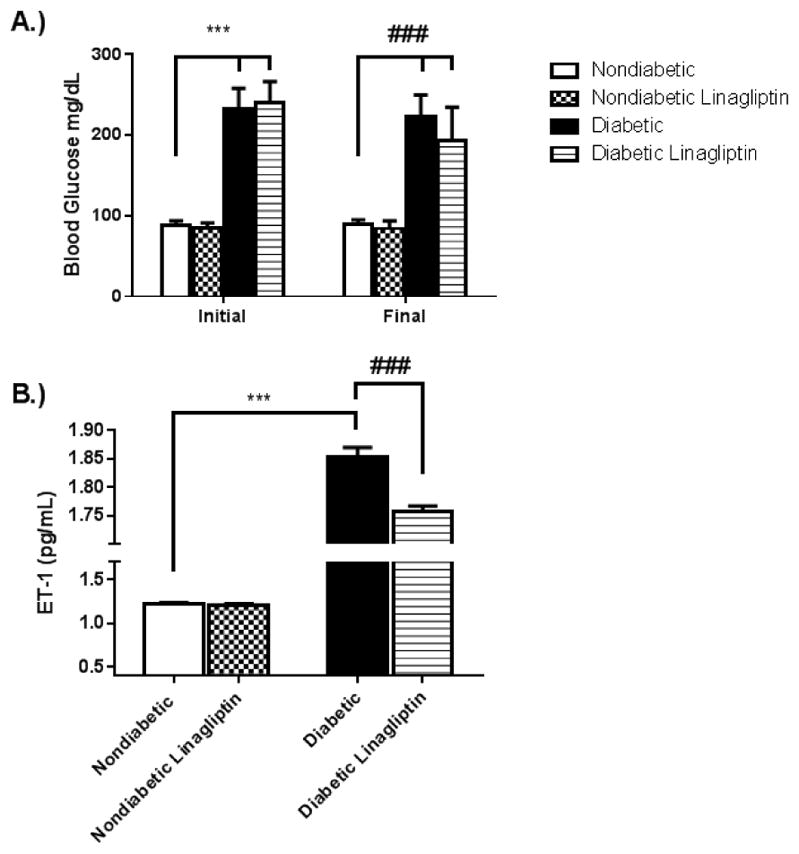

Effect of linagliptin on blood glucose levels and ET-1 plasma levels

Diabetic GK rats had significantly elevated blood glucose levels compared to non-diabetic Wistar rats, and linagliptin treatment for 4 weeks did not have any effect on blood glucose levels in either group (Fig. 1 A). ET-1 plasma levels were increased in the diabetic GK rats compared to the non-diabetic Wistar rats. Independent of any anti-hyperglycemic effects, linagliptin treatment was shown to decrease ET-1 plasma levels in the diabetic rats (Fig. 1 B).

Fig. 1. Linagliptin treatment reduces plasma ET-1 levels in diabetes independent of glycemic control.

24 week old non-diabetic Wistar (Nondiabetic) and diabetic GK (diabetic) rats were treated for 4 weeks with 166 mg/kg-chow linagliptin (Nondiabetic+Linagliptin, Diabetic+Linagliptin). (A). Blood glucose levels were assessed via tail vein puncture before and after treatment. While the diabetic rats had significantly elevated blood glucose levels compared to the nondiabetic rats, no significant changes were observed in either group following treatment. (B). Linagliptin treatment reduced plasma ET-1 levels significantly in the diabetic rats, however they were not returned to the plasma levels observed in the nondiabetic rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, n=3–5, ***p<0.001 vs Nondiabetic, ###p<0.001 vs Diabetic.

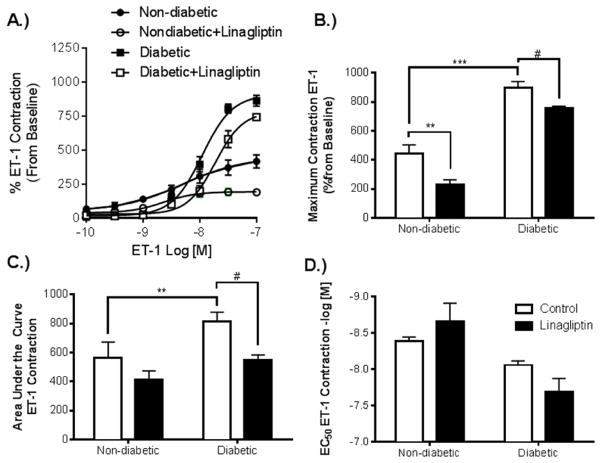

Effect of linagliptin on ET-1 mediated cerebrovascular contraction

Basilar arteries from diabetic rats exhibited an increased contractile response to ET-1 compared to nondiabetic controls. Treatment with linagliptin reduced ET-1 mediated contraction in both diabetic and non-diabetic groups (Fig. 2 A). The treatment was effective in reducing maximum contractile response in both groups (Fig. 2 B), as well as the total contraction in the diabetic group given by area under the curve (Fig. 2 C). Treatment in the non-diabetic group did show a trend towards reduction in total contraction, however this effect did not reach significance. Sensitivity to contraction with ET-1 was not found to be significantly affected by treatment with linagliptin in either the diabetic or non-diabetic groups (Fig. 2 D).

Fig. 2. Linagliptin treatment reduces contractile response to ET-1 in basilar arteries from both diabetic and non-diabetic rats.

Basilar arteries harvested from rats from each group were mounted on a DMT wire myograph for assessment of vascular function. (A). Dose response curves to ET-1 in Nondiabetic, Nondiabetic+Linagliptin, Diabetic, and Diabetic+Linagliptin were performed. (B). Diabetic arteries exhibited an increase in maximum contractile response compared to Nondiabetic arteries, and linagliptin treatment reduced this response in each group. (C). Total contraction response was improved in the diabetic group following treatment with linagliptin. (D) There was no statistically significant difference in sensitivity to ET-1 among the groups. Contractile response expressed as % increase from baseline and the results are given as mean ± SEM, n=3–5, *=p<0.05 vs. Nondiabetic, #=p<0.05 vs. Diabetic)

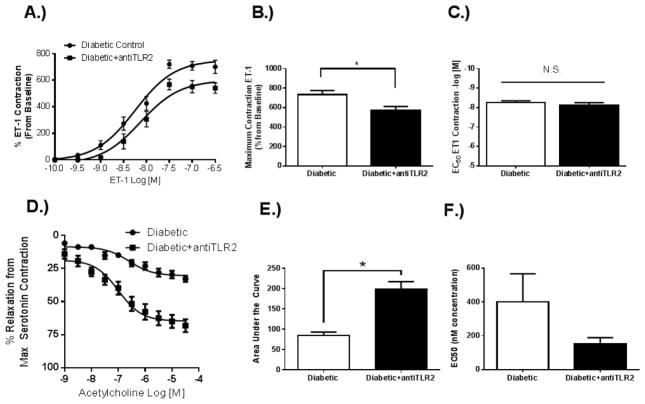

Effect of TLR2 antagonism on cerebrovascular function in diabetes

Basilar arteries from diabetic rats treated with a TLR2 antagonist were shown to have a reduction in ET-1 mediated contractility compared to vehicle control (Fig. 3 A). While maximum response to ET-1 was decreased (Fig. 3 B), sensitivity to ET-1 was not affected by TLR2 antagonism (Fig. 3 C). Endothelium dependent relaxation was also improved following antagonism of TLR2 (Fig. 3 D), with a significant reduction in total relaxation response (Fig. 3 E). Sensitivity to acetylcholine induced relaxation was not significantly affected by TLR2 antagonism (Fig. 3 F).

Fig. 3. TLR2 antagonism decreases ET-1 contraction and improves endothelium-dependent relaxation in diabetic basilar arteries.

(A). Dose response curve to ET-1 shows that antagonism of TLR2 reduces the contractile response in diabetic GK arteries (Diabetic+antiTLR2). (B). Maximum contractile response to ET-1 was decreased following TLR2 antagonism with no effect on (C) sensitivity to ET-1. (D) Dose response curve to ACh shows that antagonism of TLR2 increases endothelium dependent vasorelaxation. (E). Total relaxation response to ACh was increased following TLR2 antagonism with no effect on (F) sensitivity to ACh. Results are given as mean ± SEM, n=6/group, *=p<0.05 vs. Diabetic.

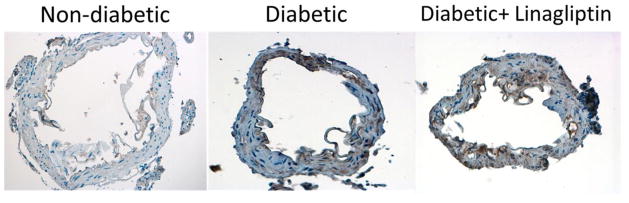

Effect of linagliptin treatment on TLR2 expression in MCAs in diabetes

Immunohistochemical staining revealed that MCAs from diabetic rats exhibit an increase in the expression of TLR2 compared to control vessels. The expression of TLR2 observed using this method was predominately seen in the vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) layers of the MCAs. Linagliptin treatment did not lead to a reduction in the expression of TLR2 in the MCA vascular smooth muscle cell layers (Fig. 4). Negative controls utilizing a non-reactive IgG antibody as well as positive TLR2 control using rat lung tissue were used to confirm the specificity of the TLR2 staining procedure (data not shown).

Fig. 4. Linagliptin treatment does not ameliorate an increase in middle cerebral artery TLR2 expression.

TLR2 expression was increased in MCAs from diabetic rats, indicated by the areas of brown staining on immunohistochemical sectioning (40X magnification). This increase was predominately noted in the medial layer of the artery, suggesting that TLR2 is increased in vascular smooth muscle cells in diabetes. Linagliptin treatment had no significant effect on the level of TLR2 expression in diabetic MCAs. Representative images from n=3–4/group shown.

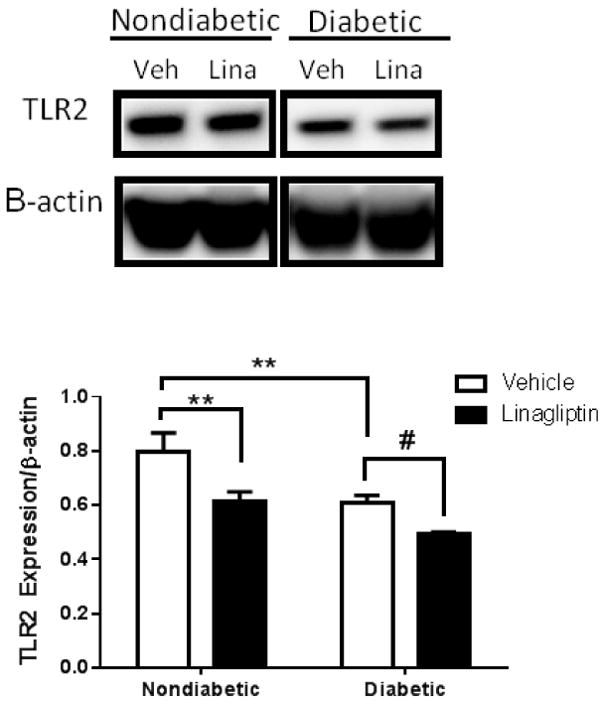

Effect of linagliptin treatment on TLR2 expression in BMVECs in diabetes

Interestingly, BMVECs isolated from diabetic GK rats were shown to have decreased expression of TLR2 compared to cells from non-diabetic Wistar rats. Linagliptin treatment significantly reduced TLR2 expression in cells from both the diabetic and non-diabetic rats (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Linagliptin treatment reduces TLR2 expression in brain microvascular endothelial cells from diabetic and nondiabetic rats.

Primary BMVECs from diabetic animals (Diabetic Veh.) exhibited a reduction in TLR2 expression compared to BMVECs from control animals (Nondiabetic Veh.). Treatment with linagliptin 100 nM significantly reduced TLR2 expression in cells from both diabetic and nondiabetic rats. Results are given as mean ± SEM, n=3/group, *=p<0.05 vs. Nondiabetic Veh., #=p<0.05 vs. Diabetic Veh.

Discussion

Our findings from the current study support the idea that diabetes induced cerebrovascular dysfunction involving the ET-1 system and endothelial TLR2 expression could be reversed using the DPPIV inhibitor linagliptin in a glucose-independent manner. Our results show that 1) increased plasma ET-1 in diabetes is reduced by linagliptin treatment independent of blood glucose levels, 2) diabetes-induced basilar artery hypercontractility to ET-1 can be ameliorated using linagliptin, 3) TLR2 antagonism can reduce ET-1-mediated contraction and improve endothelium dependent relaxation in diabetic basilar arteries, 4) linagliptin treatment does not reduce TLR2 expression in vascular smooth muscle in MCAs from diabetic rats, and 5) linagliptin treatment leads to a decrease in TLR2 expression in both non-diabetic and diabetic brain microvascular endothelial cells.

Accumulating evidence suggests that the ET system plays a role in the development and pathogenesis of diabetic cerebrovascular disease9,28. It has been shown that in the early stages of diabetes an imbalance occurs, where an increase in the presence of vasoconstrictive compounds such as ET-1 and a decrease in the bioavailability of vasodilatory nitric oxide (NO) leads to vascular dysfunction29. In previous studies from our lab using early stage type-2 diabetic GK rats, we observed that basilar arteries exhibit and increased sensitivity to ET-130. Additionally, other labs have shown using a type 1 model of diabetes that ET-1 contraction is augmented in basilar arteries from rat and rabbits31,32. We have also previously examined whether glycemic control with metformin for 4 weeks would improve cerebrovascular responses to ET-1-mediated contraction and acetylcholine induced vasodilation in diabetes. Despite blood glucose levels being significantly reduced and resorted to control levels, we did not observe an improvement in these indices of cerebrovascular function33. However, metformin was shown to exert beneficial effects on the vasculature by decreasing vascular tone and reducing plasma ET-1 levels in diabetes10. Given these findings, we chose to investigate whether another method of glycemic control used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes could have a similar effect on circulating ET-1, as well as potentially improve cerebrovascular responses.

DPPIV inhibitors are a newer class of drugs used in the treatment of diabetic patients that help to improve hyperglycemia primarily through an increase in insulin secretion and reducing glucagon levels. This is accomplished through inhibition of the proteolytic activity of DPPIV on the incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP-1, which prolongs the physiologic effect of these compounds34. The use of these drugs is highly favored in patients due to a low risk of accompanying hypoglycemia; the incretin hormones increase cyclic adenosine monophosphate in the pancreatic β-cell and thus sensitize insulin secretion to blood glucose levels using native glucose-sensing mechanisms35,36. One of the newest of the DPPIV inhibitors is linagliptin, which exerts an increased binding affinity and potency compared to other members of the drug class37. Given that treatment with DPPIV inhibitors such as alogliptin and linagliptin have been shown to improve vascular responses to endothelium dependent relaxation21,22, we chose to investigate whether linagliptin could improve ET-1 mediated cerebrovascular dysfunction in diabetes. In the current study, we have presented the novel finding that treatment with linagliptin four weeks reduces plasma ET-1 levels in diabetes. Interestingly, this decrease was not a result of a reduction in blood glucose, as levels of hyperglycemia in the diabetic animals remained unchanged following treatment. The GK rat is a non-obese, insulin resistant model of type 2 diabetes38, and thus the increase in incretin-induced insulin secretion may not be enough to overcome this insulin-resistant state and achieve glycemic control. Other studies have similarly revealed a lack of reduction of blood glucose levels in rats following treatment with linagliptin22,25. Additionally, we demonstrated that older diabetic animals with prolonged exposure to hyperglycemia exhibit an increase in ET-1 mediated basilar artery contraction, and that linagliptin treatment decreased this contractile response in both diabetic and non-diabetic vessels. We next sought to examine a possible underlying mechanism of this improvement in cerebrovascular response due to glucose-independent effects of linagliptin treatment.

It is well established that inflammation contributes to the development of diabetic vascular dysfunction39,40. Recently, the role of the innate immune system, in particular the Toll-like receptors, on the development of diabetic pathological complications has been studied. Devaraj et al.15 have shown that knockout of TLR2 reduces higher levels of inflammation in diabetes and attenuates the development of microvascular complications such as diabetic nephropathy. It has also been shown that TLR2 plays an important role in the development of vascular inflammation leading to diabetic microgangiopathy18. Importantly, it has been shown that the DPPIV inhibitors exert pleiotropic effects independent of its increase in GLP-1 and GIP-141. DPPIV inhibitors can lead to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects21,42, as well as decrease levels of TLR2 mRNA in mononuclear cells23. We thus chose to examine whether TLR2 antagonism could improve cerebrovascular function in diabetes, and whether linagliptin treatment may exert a role in this improvement.

We observed that TLR2 antagonism decreased basilar artery contraction to ET-1 and improved endothelium dependent relaxation to ACh in vessels from diabetic animals. It has been shown that TLR2 signaling inhibits eNOS activity leading to a reduction in NO bioavailability42. Thus, we believe that TLR2 signaling in the endothelial cells of the diabetic GK rats may lead to a reduction of NO bioavailability and subsequent vascular dysfunction. Levels of vasodilation in the control diabetic basilar arteries are comparable to what we have observed previously, and TLR2 antagonism was able to restore relaxation responses to comparable levels from our previous findings in non-diabetic rats10. In regards to the improvement of ET-1 mediated contraction, it has been shown that a reduction in the bioavailability of NO contributes to an increase in ET-1 levels and contractility43. While it is speculative, antagonism of TLR2 and its inhibitory effect on eNOS may be a likely mechanism for the improvement in ET-1-mediated cerebrovascular dysfunction. However, additional studies are needed to determine concentration response curves to ACh in the presence of NOS inhibition and to SNP in the linagliptin rats to confirm these results.

As ET-1 binds to ETA and ETB receptors on VSMC and ETB receptors on the endothelium to exert its effects, we sought to determine whether linagliptin treatment and its subsequent improvement on ET-1 mediated cerebrovascular dysfunction could involve TLR2 on VSMCs or BMVECs. We found that TLR2 was increased in the VSMC layer in MCAs from diabetic rats compared to control, but that linagliptin treatment did not lead to a reduction in this expression. In BMVECs however, linagliptin treatment led to a reduction in TLR2 expression in cells from both diabetic and nondiabetic rats. Paradoxically, TLR2 expression in the cells from the diabetic rats is reduced compared to the expression in cells from non-diabetic rats. It is possible that increased TLR2 signaling and downstream inflammation leads to downregulation of TLR2 expression in these cells. Mu et al.43 have shown in certain inflammatory settings that activation of other receptors such as TLR4 can downregulate the expression of TLR2, and it is possible that processes such as this are responsible for the effect we observe.

Several limitations of this study should be addressed. We recognize that while the effect of TLR2 on NO bioavailability was suggested through the improvements in endothelium dependent relaxation, that it would be beneficial to confirm this effect by determining NO levels. Additionally, an examination of the impact of linagliptin, TLR2 agonism/antagonism, and ET-1 on the expression of ETA and ETB receptors in BMVECs and VSMCs are necessary to further elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the data presented here. While future work from our lab will seek to further elucidate the connection between linagliptin and neuroinflammation through TLR2, linagliptin treatment reducing endothelial TLR2 suggests an involvement of an inflammatory pathway. Further study of the effects of the downstream signaling cascade of TLR2 in connection with the anti-inflammatory effects of linagliptin are thus pertinent. It is also possible that certain direct effects of linagliptin on cerebrovascular improvements independent of its anti-inflammatory effects could play a role in our results..

Conclusion

The present studies provides evidence that inhibition of DPPIV using linagliptin improves the ET-1 mediated cerebrovascular dysfunction observed in diabetes through a reduction in ET-1 plasma levels and reduced cerebrovascular hyperreactivity. Additionally, this effect is potentially a result of linagliptin leading to a decrease in endothelial TLR2 expression. These results strongly suggest that treatment with DPPIV inhibitors offers a therapeutic benefit independent of its anti-hyperglycemic effects for diabetic patients with established vascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Adviye Ergul is a Research Career Scientist at the Charlie Norwood Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Augusta, Georgia. This work was supported in part by VA Merit Award (BX000347), VA Research Career Scientist Award, NIH award (NS070239, R01NS083559) and a research grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. to Adviye Ergul; and American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (15PRE25760034) to Trevor Hardigan. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) and were fully responsible for all aspects of the trial and publication development.

Footnotes

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. provided both the linagliptin and financial support for the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. National Diabetes Fact Sheet. 2016 at < http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/>.

- 2.Ergul A, Li W, Elgebaly MM, Bruno A, Fagan SC. Hyperglycemia, diabetes and stroke: Focus on the cerebrovasculature. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;51:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ergul A, Abdelsaid M, Fouda AY, Fagan SC. Cerebral neovascularization in diabetes: implications for stroke recovery and beyond. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:553–63. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of large cerebral arteries and cerebral microvascular pressure. Circ Res. 1990;66:8–17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cipolla MJ. The Cerebral Circulation. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron. 2013;80:844–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edvinsson LI, Povlsen GK. Vascular plasticity in cerebrovascular disorders. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1554–1571. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ergul A. Endothelin-1 and Endothelin Receptor Antagonists as Potential Cardiovascular Therapeutic Agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:54–65. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.1.54.33505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ergul A. Endothelin-1 and diabetic complications: focus on the vasculature. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:477–82. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachidanandam K, et al. Glycemic control prevents microvascular remodeling and increased tone in type 2 diabetes: link to endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R952–R959. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90537.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AC, et al. Plasma endothelin-like immunoreactivity levels in IDDM patients with microalbuminuria. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:1038–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.8.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi K, Ghatei MA, Lam HC, O’Halloran DJ, Bloom SR. Elevated plasma endothelin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1990;33:306–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00403325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Sachidanandam K, Ergul A. Comparison of Selective versus Dual ET Receptor Antagonism on Cerebrovascular Dysfunction in Diabetes. 2011;33:185–191. doi: 10.1179/016164111X12881719352417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sachidanandam K, Harris A, Hutchinson J, Ergul A. Microvascular versus macrovascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: differences in contractile responses to endothelin-1. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:1016–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devaraj S, et al. Knockout of toll-like receptor-2 attenuates both the proinflammatory state of diabetes and incipient diabetic nephropathy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1796–1804. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.228924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takata S, Sawa Y, Uchiyama T, Ishikawa H. Expression of Toll-Like Receptor 4 in Glomerular Endothelial Cells under Diabetic Conditions. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2013;46:35–42. doi: 10.1267/ahc.13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mudaliar H, et al. The Role of TLR2 and 4-Mediated Inflammatory Pathways in Endothelial Cells Exposed to High Glucose. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mudaliar H, Pollock C, Panchapakesan U. Role of Toll-like receptors in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Sci. 2014;126:685–694. doi: 10.1042/CS20130267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma J, et al. Requirement for TLR2 in the development of albuminuria, inflammation and fibrosis in experimental diabetic nephropathy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:481–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordero OJ, Salgado FJ, Nogueira M. On the origin of serum CD26 and its altered concentration in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:1723–1747. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0728-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah Z, et al. Acute DPP-4 inhibition modulates vascular tone through GLP-1 independent pathways. Vascul Pharmacol. 2011;55:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroller-Schon S, et al. Glucose-independent improvement of vascular dysfunction in experimental sepsis by dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:140–149. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makdissi A, et al. Sitagliptin Exerts an Antinflammatory Action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3333–3341. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kröller-Schön S, et al. Glucose-independent improvement of vascular dysfunction in experimental sepsis by dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:140–149. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koibuchi N, et al. DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin ameliorates cardiovascular injury in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats independently of blood glucose and blood pressure. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:157. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0157-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdelsaid M, et al. Metformin Treatment in the Period After Stroke Prevents Nitrative Stress and Restores Angiogenic Signaling in the Brain in Diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64:1804–1817. doi: 10.2337/db14-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prakash R, et al. Enhanced Cerebral but Not Peripheral Angiogenesis in the Goto-Kakizaki Model of Type 2 Diabetes Involves VEGF and Peroxynitrite Signaling. Diabetes. 2012;61:1533–1542. doi: 10.2337/db11-1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arrick DM, Sharpe GM, Sun H, Mayhan WG. Diabetes-induced cerebrovascular dysfunction: Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Microvasc Res. 2007;73:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalani M. The importance of endothelin-1 for microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:1061–1068. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris A, et al. Effect of chronic endothlin receptor antagonism on cerebrovascular function in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1213–R1219. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00885.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alabadí J. Mechanisms underlying diabetes enhancement of endothelin-1-induced contraction in rabbit basilar artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;486:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto T, Yoshiyama S, Kobayashi T, Kamata K. Mechanisms underlying enhanced contractile response to endothelin-1 in diabetic rat basilar artery. Peptides. 2004;25:1985–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdelsaid M, Ma H, Coucha M, Ergul A. Late dual endothelin receptor blockade with bosentan restores impaired cerebrovascular function in diabetes. Life Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.12.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koliaki C, Doupis J. Incretin-based therapy: a powerful and promising weapon in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2011;2:101–121. doi: 10.1007/s13300-011-0002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuit F, Huypens P, Heimberg H, Pipeleers D. Glucose Sensing in Pancreatic β-Cells. Diabetes. 2001;50:1–11. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drucker DJ, Philippe J, Mojsov S, Chick WL, Habener JF. Glucagon-like peptide I stimulates insulin gene expression and increases cyclic AMP levels in a rat islet cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3434–3438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doupis J. Linagliptin : from bench to bedside. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014:431–446. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S59523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akash MSH, Rehman K, Chen S. Goto-kakizaki Rats: Its Suitability as Non-obese Diabetic Animal Model for Spontaneous Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2013;9:387–396. doi: 10.2174/15733998113099990069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Creager MA, Libby P. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part I. Circulation. 2003;108:1527–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091257.27563.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolluru GK, Bir SC, Kevil CG. Endothelial Dysfunction and Diabetes: Effects on Angiogenesis, Vascular Remodeling, and Wound Healing. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:1–30. doi: 10.1155/2012/918267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulvihill EE, Drucker DJ. Pharmacology, Physiology, and Mechanisms of Action of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors. Endocr Rev. 2014;35:992–1019. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira L, et al. Effects of Sitagliptin Treatment on Dysmetabolism, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in an Animal Model of Type 2 Diabetes (ZDF Rat) Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2010/592760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mu HH, Pennock ND, Humphreys J, Kirschning CJ, Cole BC. Engagement of Toll-like receptors by mycoplasmal superantigen: downregulation of TLR2 by MAM/TLR4 interaction. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:789–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]